Twelve

It Must Mean …

Something

In Brief

‘Descartes and the Gut: “I’m Pink Therefore I Am”’

by D. G. Thompson (published in Gut, 2001)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Foul words for referees. • The decline of public insult in London • How beats the poet’s heart, electrically • The the the the the the the the the the the, in order • The scholar’s colon • Bad highlighting • Dude • Bob, by the look of him • Gówsü; Déznep; Wítaw; Thôbonf; Mávquawpûnt; Stisk • ’Meaning’ meaning ‘meaning’

The Curse of the Referee

Do swear words have predictable effects on football referees? A team of Austrian scientists tackles that question in a study called ‘May I Curse a Referee? Swear Words and Consequences’. Stefan Stieger, of the University of Vienna, together with Andrea Praschinger and Christine Pomikal, who describe themselves as ‘independent scientists’, published their report in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine.

Football referees enforce the laws of the game set forth by the sport’s governing organization, FIFA (the Fédération International de Football Association). The pertinent regulation is FIFA’s Law 12 (‘Fouls and Misconduct’), whose very last section – Section 81 – simply says: ‘A player who is guilty of using offensive, insulting or abusive language or gestures must be sent off.’

Stieger, Praschinger, and Pomikal performed their research in two steps. First, they obtained some swear words. Then, obscenities in hand, they found some referees who were willing to answer a survey.

The team began by drawing up a list of one hundred potential swear words. They pared the list by recruiting thirteen German-speaking residents of Austria, six women and seven men. Each Deutsch-Lautsprecher evaluated each word, rating both its degree of insultingness and whether it could be properly applied to both men and women. ‘Participants [also] had to rate the insulting content of each swear word. Does the swear word concern the person’s power of judgment (e.g., blind person), intelligence (e.g., fool), appearance (e.g., fatso), sexual orientation (e.g., bugger), or genitals (e.g., crap)?’

The researchers then found 113 game game referees from across Austria, and posed the following situation to each of them: during a stoppage in play, one team’s captain comes up to you and suggests you make a particular ruling. You decline. ‘Hereupon the team captain says … (the swear word mentioned below), turns around and walks [away].’ Do you, the referee, respond by issuing (1) a red card or (2) a yellow card or (3) an admonition, or do you (4) do nothing at all? The referee was asked this for each of the twenty-eight swear words.

Their answers showed a clear pattern. ‘Analyzing all swear words independent of their offensive nature, it was found that 55.7% of the swear words would have received a red card, although Law 12 would have prescribed a red card in all cases.’ Only a very few officials would always, automatically, eject the player.

Digging into the nitty-gritty of the data, the researchers gained two general insights. First, ‘that the decision to assign any card was dependent on the insulting content of the swear word’. Second, that ‘referees would have issued a red card for sexually inclined words or phrases rather than for terms insulting one’s appearance’.

Praschinger, Andrea, Christine Pomikal, and Stefan Stieger (2011). ‘May I Curse a Referee? Swear Words and Consequences.’ Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 10: 341–45.

May We Recommend

‘Swearing as a Response to Pain’

by Richard Stephens, John Atkins, and Andrew Kingston (published in Neuroreport, 2009, and honoured with the 2010 Ig Nobel Prize in peace)

Injury to Insult

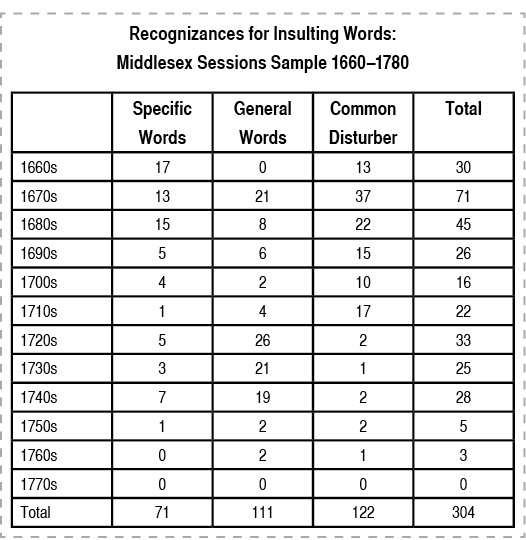

Insults just aren’t what they used to be, according to a study called ‘The Decline of Public Insult in London 1660–1800’. The study’s author, Robert B. Shoemaker, teaches eighteenth-century British history at Sheffield University, in the UK.

Professor Shoemaker pored through records of court proceedings from the late sixteenth through the early nineteenth centuries, paying special attention to the insults. Time was, insulting someone in public – or even in private – could easily propel you into court, and thence, if the insult was good or your luck wasn’t, to jail.

Shoemaker charted the number of insult-fuelled prosecutions in the consistory court of London over those centuries. ‘The pattern is clear’, he writes, ‘a massive increase in the late sixteenth century to a peak in the 1620s and 1630s, followed by a collapse ... By the late eighteenth century per capita prosecutions in London had fallen to only one or two per 100,000 per year.’ By the late 1820s, the number of prosecutions had dropped to an insulting one or two, total, per year.

(The high point for legal action, by the way, was 1633, the year Samuel Pepys was born. One can only speculate at how much more colourful his famous diary might have been had Pepys lived a generation earlier, during London’s golden age of insult.)

As the years rolled by, individual nasty words lost some of their power to trigger prosecution. Legal proceedings dealt, instead, with more general allegations. Court documents became less fun to read, with fewer bold, juicy epithets, the accusations now built of mushy phrases such as ‘opprobrious names’, ‘scandalous abuse’, or ‘grossly insulting’.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries revolutionized the legal handling of insult, Shoemaker suggests in telling us that ‘the very nature, function and significance of the insult was changing over this period’.

He invokes the words of King’s College London historian Laura Gowing. Gowing emphasized that in earlier years, ‘Defamations rarely happened inside private houses, at meals, or within private conversation, but were staged, often in the open, with an audience provided by the witnesses who, “hearing a great noise” in the street, left their work or houses to investigate or intervene ... the doorstep was a crucial vantage point for the exchange of insult.’

But by the eighteenth century, Shoemaker reports, ‘the insult became less public’. Insults moved indoors. Many ‘took place in semi-private locations, such as yards, shops, pubs and houses, where there were not always many witnesses’. Also, ‘there was much less certainty about whether defamatory words automatically destroyed reputations’, and so, ‘correspondingly, the power of insulting words was declining’.

All this tells us something sad about modernization: ‘At a basic level, due to frequent geographical mobility eighteenth-century Londoners did not know or take an interest in the activities of their neighbours as much as they used to.’

In this view of things, public insults declined because modern citizens no longer loved their neighbours.

Shoemaker, Robert B. (2000). ‘The Decline of Public Insult in London 1660–1800.’ Past and Present 169 (1): 97–131.

Measures of Poetry

Poetry is said, by poets, to make the heart flutter and the breath catch. A team of German, Swiss, and Austrian scientists showed that the claim is quite true, at least under certain laboratory conditions.

The researchers tried to describe this lyrically. They sought, they say, ‘to investigate the synchronization between low frequency breathing patterns and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) of heart rate during guided recitation of poetry’.

Twenty healthy individuals volunteered to spend twenty minutes reading aloud hexameter verse from ancient Greek literature. These volunteers were German speakers. They read a passage from a German translation of Homer’s heart-pounding, breath-forcing epic The Odyssey. In accordance with modern sensibilities, the research protocol was approved beforehand by an ethics committee. The study was published in the American Journal of Physiology – Heart and Circulatory Physiology.

Dr Dirk Cysarz, of the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke in Germany, led the team. He loves studying matters of the heart and lungs, especially the ways in which those organs exhibit rhythm and pacing. Other group members have spent their careers delving, variously, into the mysteries of mathematics, music, and speech problems.

To any volunteer who was unversed in the methods of modern medical experimentation, the recitation would have seemed unexpectedly complex. In ancient Greece, reciting poetry was a simple process. One stood or sat, unencumbered, and spoke. But here, now, there were strings attached. The Greeks, anyway, would have called them strings. We call them electrical wires.

Whilst spouting Homer from the lips, each volunteer was also sending electrical signals straight from his or her heart, via a transducer and wires, to a solid-state electrocardiogram recording apparatus.

And that’s not all. The poetry-reciting, electrical-pulse-generating volunteer also supplied streams of information about his or her nasal and oral airflow. Three thermistors were mounted next to the nostrils and in front of the mouth. Thermistors are little electronic devices that measure temperature change – in this case between warm, exhaled air and cooler, about-to-be-inhaled air. Thus were the nuances of breath and pulse documented, forming a record of each volunteer’s poetico-physiological experience.

The scientists gathered up a potentially blooming, buzzing confusion of data. To make sense of it, they used statistical and other mathematical tools that, for the most part, did not exist in the time of Homer: time-series band-pass filtering; Fourier transforms; Hilbert transforms; RR-tachograms.

The result of all this is summed up in the title of their study: ‘Oscillations of Heart Rate and Respiration Synchronize During Poetry Recitation’. Though expressed in somewhat technical language, it accords with the belief of millennia of declaiming poets. The synchronization, we now know, is not perfect. But the project brings us ever-so-slightly closer to understanding poetry, inspiration, and exhalation, by the numbers.

Cysarz, Dirk, Dietrich von Bonin, Helmut Lackner, Peter Heusser, Maximilian Moser, and Henrik Bettermann (2004). ‘Oscillations of Heart Rate and Respiration Synchronize During Poetry Recitation.’ American Journal of Physiology – Heart and Circulatory Physiology 287: H579–87.

Where The –

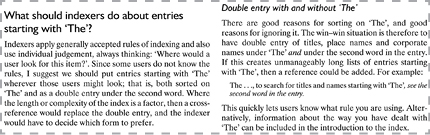

‘The’ has its place. That, more or less, is the theme of Glenda Browne’s treatise entitled ‘The Definite Article: Acknowledging “The” in Index Entries’.

The ‘The’ article appears in The Indexer, the information- and fun-packed publication for professional indexers everywhere. The Indexer has its own index, which includes an entry for Browne, Glenda.

Browne characterizes herself as an Australian freelance indexer. Her study is a four-page guide for the definitely perplexed. It explains: ‘If “The” exists in a name or title, it should exist in the index entry for that name or title. And if it exists in the index entry, it should be taken into account when sorting the entries.’

The problem is widespread, and although there are rules (at least three different – and differing – official sets of rules), indexers often go their own ways. Browne gives examples. In the 2000/2001 Sydney telephone directory, ‘“Agency Register The” and “Agency Personnel The” are sorted under “A”, while “The Agency Australia” is sorted under “The”. “The Sausage Specialist” is filed under “The” and “Sausage”, while “The Meat Emporium” is only filed under “Meat Emporium The”.’

Browne says, ‘“The” often doesn’t matter. There are many titles that include “The”, but then treat it as if it doesn’t exist. The masthead of [the newspaper] The Australian, for example, has a tiny “The” above a large “Australian”. Their layout tells us that The is insignificant, but they won’t follow this through and omit it entirely. Corporate names such as “The University of Queensland” are used at times with, and at times without, an initial “The”. This makes it very difficult for users to know whether “The” is an integral part of the name.’

‘On the other hand,’ she continues, ‘in many corporate names “The” has been deliberately chosen as the first word of the name, and is used consistently. The musical group “The Beatles” is referred to as such, and never as “Beatles”. In these cases, the group considers the initial article significant, and it will be the access point consulted by many users. An extreme example is the group “The The”, which would look absurd with the initial “The” omitted or inverted.’

There are good reasons for sorting on ‘The’, says Browne, and good reasons for ignoring it. She suggests listing ‘The’ items twice: under ‘The’ and under the second word in the entry. Lest that create unmanageably long lists of entries starting with ‘The’, she offers other alternatives.

Win-win situation proposed by Glenda Browne, the.

Internationally, the ‘The’ problem is not the problem – it is merely a problem. Browne makes this clear at the very start of her paper, with a quotation from indexing maven Hans H. Wellisch: ‘Happy is the lot of an indexer of Latin, the Slavic languages, Chinese, Japanese, and some other tongues which do not have articles, whether definite or indefinite, initial or otherwise.’

For her study of the ‘The’ problem, Glenda Browne was awarded the 2007 Ig Nobel Prize in literature.

Browne, Glenda (2001). ‘The Definite Article: Acknowledging “The” in Index Entries.’ The Indexer 22 (3): 119–22.

To Wrestle a Bad Metaphor

Carl Phillips, Brian Guenzel, and Paul Bergen are hopping mad about bad metaphors. Writing in the almost-poetically-named Harm Reduction Journal, they pull on their metaphorical boxing gloves. Stepping into the ring, so to speak, they issue a forthright statement: ‘Anti-harm-reduction advocates sometimes resort to pseudo-analogies to ridicule harm reduction. Those opposed to the use of smokeless tobacco as an alternative to smoking sometimes suggest that the substitution would be like jumping from a 3-story building rather than 10-story, or like shooting yourself in the foot rather than the head.’ Following their summary of these two disagreeable metaphors, Phillips, Guenzel, and Bergen then proceeded to administer a good thrashing.

They collected several versions of the ‘jump from a building’ metaphor. Some metaphor makers, they report, have ‘likened smoking to falls from at least the 10th floor and smokeless tobacco to falls from at least the 3rd; we found numbers as high as 50 and 30’. These are beneath contempt, they explain, because ‘anyone with passing familiarity with the human body and Earth’s gravity should be aware that falls from the 10th story are almost always fatal’.

Perhaps unsure of their own familiarity with the human body and Earth’s gravity, they conducted a review of the available literature on mortality rates as a function of free-fall distance.

‘It is surprising’, they write, ‘how little information is published on the topic ... The literature suggests that falls from up to the 3rd story are most always survived, with the death rate increasing sharply and approaching 100% over the next three or four stories ... More accurate analogies might actually be fairly useful in painting the picture for consumers. A nontrivial portion of young men have probably jumped from a 2nd story window, but few would dare jump from the 4th.’

This is their main line of attack. They go at it from other directions, too.

In the second bout, they pummel the ‘gunshot to the head’ metaphor, applying a devastating one-two punch:

- ‘It is immediately obvious that the gunshot metaphor is absurd: If someone was faced with the choice of shooting himself in the head and shooting himself in the foot or leg, the latter option is quite obviously better from a health outcomes perspective.’

- ‘Mortality risk from self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the head dwarfs that from smoking, while foot wounds, though they have a low mortality rate, have a high probability of permanent debilitating orthopedic damage, a risk absent in tobacco use.’

Phillips and Bergen are at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Guenzel is at the Center for Philosophy, Health, and Policy Sciences in Houston, Texas.

In the end, they let slip what’s most got up their nose. ‘The metaphors’, they write, ‘exhibit a flippant tone that seems inappropriate for a serious discussion of health science.’

Phillips, Carl V., Brian Guenzel, and Paul Bergen (2006). ‘Deconstructing Anti-harm-reduction Metaphors: Mortality Risk from Falls and Other Traumatic Injuries Compared to Smokeless Tobacco Use.’ Harm Reduction Journal 3: 15.

In Brief

‘The Case of the Burly Wee Man’

(published in the Archives of Environmental Health, 1974)

Colonoscopy Sociologica

The passing years make it difficult to remember how much excitement arose when Sue Ziebland and Catherine Pope published their epic report ‘The Use of the Colon in Titles of British Medical Sociology Conference Papers, 1970 to 1993’.

Ziebland was then at the department of public health medicine of the Camden and Islington health authority in London. She has since passed through the digestive system of academia and emerged at the University of Oxford. Pope was at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Time and circumstance have deposited her at the University of Bristol.

Together Ziebland and Pope explored the colons of several British researchers. Their report appeared in the Annals of Improbable Research. It shed light on a problem that distressed many social scientists: how to properly devise the titles of their conference papers. This is how Ziebland and Pope described it: ‘Unless the presenter is of an unusually retiring disposition, there will be a desire to choose a punchy, attention-grabbing title in the hope of attracting a large and lively audience. However, sooner or later the truth will out, and it is clearly in one’s interest to make some mention of the actual subject of the work. The favoured solution is to use a colon, separating the snappy from the prosaically descriptive, as in: “Sex and Drugs: Women’s Use of Aspirin”.’

Ziebland and Pope examined trends in the use of the colon in paper titles using evidence from a particular annual conference. They considered every paper that was listed in the printed programmes from the first annual conference in 1969, up to the 1993 meeting.

Their analysis is based on the percentage of the total number of papers per year that include one or more colons in the title. They tallied each paper as a single occurrence, even a 1979 paper that included five colons. (Alas, they do not tell us the name of that paper.)

They discovered that the percentage of paper titles increased almost continuously during the 1970s and 1980s. From the mid-1980s onwards, a steady forty to forty-eight percent of titles included a colon. In the year 1985, a staggering fifty-seven percent featured colons. This anomaly, Ziebland and Pope wrote, ‘has no obvious explanation’.

The colon has fascinated scholars for generations. More than a decade before Ziebland and Pope’s colonic examination, the noted and footnoted scholar J. T. Dillon, of the University of California, Riverdale, performed three historical endoscopies of the academic colon. They are:

The Emergence of the Colon: An Empirical Correlate of Scholarship (American Psychologist, 1981)

Functions of the Colon: An Empirical Test of Scholarly Character (Educational Research Quarterly, 1981)

In Pursuit of the Colon: A Century of Scholarly Progress: 1880–1980 (Journal of Higher Education, 1982)

Incisive and exciting as these studies may have been when published, they are now seen as period pieces.

Highlights of Highlighting

The practice of reading textbooks for pleasure is just as lively now as it has ever been. More people buy textbooks – actually spend their own money to do it – now than ever before. And in deciding what to buy, they (or should I say, ‘we’) are kids in a candy shop. There is an ever-growing number of specialized subjects for which textbooks exist, and so the variety of textbooks on offer is always increasing. Even if you somehow manage to exhaust the cream of one genre, you can easily find another to sample.

An untimid reader can find lots of good, meaty reads packed with literary merit. Like the best novels, many of the textbooks in forestry management, ergodic theory, multinational auditing, and thousands of other genres try to fill a reader’s mind with ideas and words that, at first read, really do feel completely novel.

But that’s not the best part. Used textbooks offer one thing more to beguile the leisure-time reader.

For many of us, the highlight of reading used textbooks is the highlighting, the lines previous readers have drawn under, around, or through particular words or passages. Good highlighting makes any used textbook worth the purchase. Bad highlighting makes it even better. And in buying highlighted textbooks, you sometimes get a double bonus: despite the carefully added interest, they often have drastically reduced price tags.

Of course, not everyone’s pulse races at the sight of a textbook. H. G. Wells was outspoken about this. In 1914, he put textbooks in their supposed place, which to him was fifth in a list of derogatory words he used to describe bad education: ‘thin, ragged, forced, crammy, text-bookish, superficial’. Wells, for all his insights into science, into humanity, into the future, into the etc., was somehow not seeing the good parts – not even the highlights! – of textbooks.

Vicki Silvers and David Kreiner, of Central Missouri State University, stepped on to the scene eighty-three years later, with a study called ‘The Effects of Pre-Existing Inappropriate Highlighting on Reading Comprehension’. ‘Textbook highlighting is a common study strategy among college students’, Silvers and Kreiner wrote, using the academese that their profession demands. Then they described their experiments.

First, they had students read a passage of text. Some students had text that was highlighted appropriately. Some had text that was highlighted inappropriately. Others had Spartan, unhighlighted text. Silvers and Kreiner then tested how well the students comprehended the text. Those with the inappropriate highlighting scored much lower than the others. A second experiment showed that even when students were warned about the inappropriate highlighting, they had trouble ignoring it.

In 2002, Silvers and Kreiner were awarded the Ig Nobel Prize in literature. At the awards ceremony, they offered one piece of advice: ‘Don’t buy a textbook that was highlighted by an idiot.’ I’m not sure I’d agree.

Silvers, Vicki, and David Kreiner (1997). ‘The Effects of Pre-Existing Inappropriate Highlighting on Reading Comprehension.’ Reading Research and Instruction 36: 217–23.

Hey, Dude…

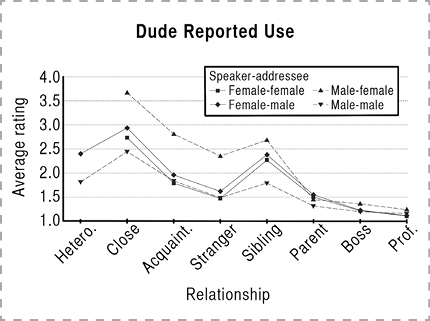

The story of dude – its rise, its role, its rich history as a word – takes twenty-five pages to tell. University of Pittsburgh linguistics professor Scott Fabius Kiesling’s analysis of dude carries the title ‘Dude’. It occupies a stylish chunk of the autumn 2004 issue of the journal American Speech.

Kiesling’s tale accords with the pithy history of dude that you’ll find in the Oxford English Dictionary. Of American origin, dude in the 1880s was ‘a name given in ridicule to a man affecting an exaggerated fastidiousness in dress, speech, and deportment’. A few decades later, a dude was ‘a non-westerner or city-dweller who tours or stays in the west of the US, especially one who spends his holidays on a ranch; a tenderfoot’. Nowadays, a dude is the object of more-than-just-self-esteem. Today’s dude is ‘any man who catches the attention in some way; a fellow or chap, a guy. Hence also approvingly, especially applied to a member of one’s own circle or group.’

Kiesling delves deep into the modern dude, the dude of whom we hear speak wherever young Americans roam. He provides context for those whom the world may have passed by. ‘Older adults’, he writes, ‘baffled by the new forms of language that regularly appear in youth cultures, frequently characterize young people’s language as “inarticulate”, and then provide examples that illustrate the specific forms of linguistic mayhem performed by “young people nowadays”.’

He then gets down to business, outlining ‘the patterns of use for dude, and its functions and meanings in interaction’. Dude, we learn, is: (a) used mostly by young men to address other young men; (b) a general address term for a group (same or mixed gender); and (c) a discourse marker that generally encodes the speaker’s stance to his or her current addressee(s). Best of all, ‘Dude indexes a stance of cool solidarity, a stance which is especially valuable for young men as they navigate cultural Discourses of young masculinity.’

Note from study: The label ‘Hetero’ refers to ‘heterosexual intimate relationships’, and though ‘there were responses for male-male and female-female categories ... it is clear from the students who gathered the data that not all respondents understood the intimate nature of this category’

Kiesling attributes the sudden blossoming of dude, in the 1980s, to the actor Sean Penn, who played the role of Jeff Spicoli in the film Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Penn, in his Spicoli persona, is ‘the do-nothing, class-cutting stoned surfer’ who takes ‘a laid-back stance to the world, even if the world proves to be quite remarkable’. Kiesling confides that he was a teenager at the time the film came out, and that ‘many young men glorified Spicoli, especially his nonchalant blindness to authority and hierarchical division’.

The bulk of ‘Dude’ is technical, an exploration of data gathered by students in Pittsburgh. Each student wrote down the first twenty usages of the word ‘dude’ they heard during a three-day period. These Kiesling compiled into what he calls ‘The Dude Corpus’. The corpus awaits the scrutiny of future dudes and scholars of dude, who may see in it things that are invisible to us.

Kiesling, Scott F. (2004). ‘Dude.’ American Speech 79 (3): 281–305.

Hazards of Bobbing

New parents beware! is the implied theme of a new study called ‘Who Do You Look Like? Evidence for the Existence of Facial Stereotypes for Male Names’.

The researchers begin with this little shocker: ‘Choosing a name for a forthcoming baby occupies a good deal of time for most expectant parents ... Few worry about whether the name will provoke a facial stereotype in the minds of others (hmm ... he doesn’t look like a “Bob”), but, as the present research suggests, this may be yet another potential worry to have when one selects a name for one’s progeny.’

Scientists Melissa A. Lea, Robin D. Thomas, Nathan A. Lamkin, and Aaron Bell hammer home the unfairness of the situation. ‘This is an especially provocative suggestion’, they write, ‘as names are usually chosen before or immediately after birth, certainly before any knowledge becomes available of what the child may look like when they are adults.’

All of the team members are associated with Miami University of Ohio. The university issued a press release that announced ‘researchers at Miami University think they know why you can remember some peoples’ names but not others’. They’ve shown quantitatively that certain names are associated with certain facial features. For example, when people hear the name “Bob” they have in mind a larger, round face than when they hear a name such as “Tim” or “Andy”.’

The study includes a pair of photos – on the left, a tousle-haired young man in a white shirt; on the right a bald, droopy-eyed fellow wearing what might be a striped prison outfit. The researchers say, when shown these two pictures, ‘audience members overwhelmingly agree that the man on the left is named “Tim” and the man on the right is named “Bob”.’

Figure: ‘Audience members overwhelmingly agree that the man on the left is named “Tim” and the man on the right is named “Bob”.’

This, however, was not what happened in the experiment.

In the experiment, software was used to create idealized, hairless faces for each of fifteen names: Andy, Brian, Joe, Justin, Rick, Bill, Dan, John, Mark, Tim, Bob, Jason, Josh, Matt, and Tom. Then a group of volunteers was given printed cards – each card had one of those pictures or one of those names – and told to match up pictures and names.

Most agreed that Bobs are Bob-like. Many agreed that the Bills are Bill-like and that the Toms are Tom-like. There was not so much agreement as to the other faces and names.

Of course, these research results are definitive only for those particular faces and those particular names, and only as they struck one particular group of student volunteers on one particular day.

The researchers say they were inspired, at least a little, by a study done nearly a century ago. In 1916, a researcher based at Cornell University, in Ithaca, New York, wanted to understand what she called ‘the nature of the psychological response to proper names of unknown persons’. Basically, she asked: What sort of person is named Rupzóiyat?

In particular, the researcher, who herself was named G. English, wanted to test a theory proposed by a Swiss psychologist named Édouard Claparède. The theory says that, ‘other things equal, names consisting of heavy or repeated syllables call forth images of fat, heavy-set, bloated, or slightly ridiculous individuals; a short and sonorous name, on the other hand, suggests slender and active persons, etc.’.

English concocted fifty ‘nonsense names’ – names stuck together with syllables she chose at random. Then she tested the names on eight people. Here’s how she described the experiment: ‘Each name was pronounced three times over, the experimenter being careful to pronounce it slowly, distinctly, and (as nearly as possible) always in the same manner. [Then the observer was asked] to describe the person that “must belong to the name”.’

English’s fifty names: Chérin, Póisher, Kilom, Koikert, Vázal, Dáwfisp, Zóque, Spren, Dáwthô, Rupzóiyat, Blag, Lísrix, Thaspkûwhin, Kîrd’faumish, Génras, Tháchô, Brob, Zóitû, Kóldak, Múrbix, Chermtgáwkonv, Bóppum, Vúshap, Grib, Watshóiquol, Móiki, Hoxzáuwhuk, Gáwthû, Zé’the, Gówsü, Déznep, Wítaw, Thôbonf, Mávquawpûnt, Stisk, Tówbant, Táquû, Skamth, Quajnûmeth, Bünoy, Drup, Gúklal, Pófmoj, Spux, Jíkzel, Snemth, Thúbtawkarnth, Línrêwex, Gronch, and Túpjoz.

English also asked the observers to try to spell the names back to her. She didn’t care whether they got the spelling right. She just wanted to ensure that they had heard her clearly.

The results disappointed her: ‘In only five cases was there anything like agreement among all observers as to sex or other characteristics. Rupzóiyat was reported as a young man by all observers; Bóppum was said to be a tall, fat or large man by six observers.’ Of the eight observers, ‘five thought Zé’the must be a girl; six reported Grib as a small man; and five reported Kîrd’faumish as a strong or big man. For all the remainder there was disagreement.’

English decided that ‘there is no constant or uniform tendency among these observers [to] imagine a similar type of individual for the same name.’

She mused about the way Charles Dickens played with nonsense names. But she concluded that maybe Dickens – and maybe all of us – only occasionally see a person’s name as some sort of guide to their nature: ‘We know that Dickens came to [evolve the name] Chuzzlewit through Sweezleden, Sweezleback, Sweezlewag, Chuzzletoe, Chuzzleboy, Chubblewig, and Chuzzlewig. The name was significant to him; and yet there were various types of Chuzzlewit, as there were various types of Nickleby. Indeed, the applicability of a surname to all the members of a family must, one would suppose, tend to prevent our attaching any special import to the name’s physiognomy.’

Lea, Melissa A., Robin D. Thomas, Nathan A. Lamkin, and Aaron Bell (2007). ‘Who Do You Look Like? Evidence for the Existence of Facial Stereotypes for Male Names.’ Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 14 (5): 901–7.

English, G. (1916). ‘On the Psychological Response to Unknown Proper Names.’ American Journal of Psychology 27: 430–34.

Call for Investigators

The Rhyming Monikers Research Citation Bibliography Project, announced here, is searching for additions to its collection of outstanding research on which the co-authors names rhyme.

Definition : For the purposes of the project, a Rhyming Moniker involves sound correspondence in at least the terminal syllable of the co-authors’ surnames. The first specimen in the collection, unearthed by Investigator Russell Mortishire-Smith, serves as a model organism:

‘Measurement of Long-Range 13C-13C J Couplings in a 20-kDa Protein-Peptide Complex’ by Ad Bax, David Max, and David Zax (published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society , 1992). The authors are at what is abbreviatingly referred to as the Lab. Chem. Phys., Natl. Inst. Diabetes Dig. Kidney Dis., Bethesda, Maryland.

Bax, Max, Zax. The names ring out. They sing out. An impressive contribution.

Purpose : The collection will be made available to other researchers for cross-variable and meta-analysis.

If you have identified a new specimen, please send to marca@improbable.com with the subject line:

RHYMING MONIKERS RESEARCH CITATION COLLECTION

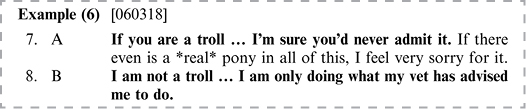

Trolling for Annoyance

Trolls – call them Internet trolls, if you like – are distant behavioural kin to Plasmodium falciparum, a protozoan parasite that causes malaria in large numbers of human beings. Both kinds of parasite are maddeningly difficult to suppress. They manage, again and again, to return after we thought we’d seen the last of them. Each can, if left untreated, cause agony or worse.

These trolls infect any place where people gather electronically to converse by writing comments to each other. Trolls creep into and crop up anywhere they can, wheedling for attention in chat rooms, listservs, twitter streams, blogs, and as you may have noticed, in the comments section of online news articles.

One of the many annoying things about Internet trolls is that it’s difficult to define precisely, with academic rigour, what they do. Claire Hardaker, a lecturer at University of Central Lancashire’s department of linguistics and English language, took up the challenge. Her study called ‘Trolling in Asynchronous Computer-Mediated Communication’ is published somewhat counter-intuitively in the Journal of Politeness Research.

Hardaker presented an early form of the paper to a mostly troll-free audience at the Linguistic Impoliteness and Rudeness conference held at her university in 2009.

After much research and hard work, Hardaker came up with a working definition. A troll is someone ‘who constructs the identity of sincerely wishing to be part of the group in question, including professing, or conveying pseudo-sincere intentions, but whose real intention(s) is/are to cause disruption and/or to trigger or exacerbate conflict for the purposes of their own amusement’.

Detail: Trolling for an annoying example

She arrived at this after much trolling (in a very different sense of that word) through data. Lots of data. A ‘172-million-word corpus of unmoderated, asynchronous computer-mediated communication’, a nine-year collection of commentary in an online discussion group about horseback riding. She focused in on the huge number of passages where people mentioned trolls, trolling, trolled, trollish, trolldom, and other variations on the key word ‘troll’.

Distilling the wisdom of the horse-talk crowd, Hardaker set up this handy guide to interacting with trolls: ‘Trolling can (1) be frustrated if users correctly interpret an intent to troll, but are not provoked into responding, (2) be thwarted, if users correctly interpret an intent to troll, but counter in such a way as to curtail or neutralize the success of the troller, (3) fail, if users do not correctly interpret an intent to troll and are not provoked by the troller, or, (4) succeed, if users are deceived into believing the troller’s pseudo-intention(s), and are provoked into responding sincerely. Finally, users can mock troll. That is, they may undertake what appears to be trolling with the aim of enhancing or increasing affect, or group cohesion.’

Any comments?

Hardaker, Claire (2010). ‘Trolling in Asynchronous Computer-Mediated Communication: From User Discussions To Academic Definitions.’ Journal of Politeness Research 6 (2): 215–42.

In Brief

‘Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly’

by Daniel M. Oppenheimer (published in Applied Cognitive Psychology and honoured with the 2006 Ig Nobel Prize in literature)

The Psychology of Repetitive Reading

A typical adult knows almost nothing about the psychology of repetitive reading. This is not surprising. Research psychologists, as a group, know little about the subject, though some have attempted to close the gap.

Human beings can be induced to read repetitively. In one experiment, a scientist named N. Borgovsky asked two hundred subjects to read a repetitive essay. The essay consisted of a single paragraph repeated several times. Each subject was told beforehand that the essay was highly repetitive. The result was surprising. Ninety-two percent of the subjects read the essay completely from beginning to end.

Borgovsky began his experiment by recruiting several dozen people, whom he asked to be his research subjects. A typical adult knows almost nothing about the psychology of repetitive reading. (This is not surprising. Research psychologists, as a group, know little about the subject, though some have attempted to close the gap.) So Borgovsky sat his subjects down in a room, and explained that human beings can be induced to read repetitively. In one experiment, he told them, a scientist asked two hundred subjects to read a repetitive essay. The essay consisted of a single paragraph repeated several times. Each subject was told beforehand that the essay was highly repetitive. The result was surprising. Ninety-two percent of the subjects read the essay completely from beginning to end.

After giving his subjects that background information, Borgovsky described his own experiment in great detail. The experiment was based on a book he had read. The book was based on the idea that human beings can be induced to read repetitively. In one experiment, a scientist asked two hundred subjects to read a repetitive essay. The essay consisted of a single paragraph repeated several times. Each subject was told beforehand that the essay was highly repetitive. The result was surprising. Ninety-two percent of the subjects read the essay completely from beginning to end.

After Borgovsky carried out his experiment, he published a report. Called ‘The Psychology of Repetitive Reading’, it explains that human beings can be induced to read repetitively. In one experiment, a scientist – Borgovsky, in fact – asked two hundred subjects to read a repetitive essay. The essay consisted of a single paragraph repeated several times. Each subject was told beforehand that the essay was highly repetitive. The result was surprising. Ninety-two percent of the subjects read the essay completely from beginning to end.

Meaning? Meaning? Meaning?

Yes, yes, yes – there are many ways to repeat yourself. Some are more meaningful than others, says a clever linguist in the Netherlands.

Technically speaking, ‘Yes, yes, yes!’ is an example of ‘multiple sayings in social interaction’. Tanya Stivers has pursued, bagged, and intensively studied a small herd of multiple sayings. Her thirty-three-page report about them, called ‘“No no no” and Other Types of Multiple Sayings in Social Interaction’, was published in the journal Human Communication Research.

Stivers is based at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, in Nijmegen, The Netherlands. She decided to look at just one species in the multiple-sayings menagerie. The repetition ‘Okay okay okay’ interests Stivers a lot. The repetition ‘Okay. Okay. Okay’ does not.

‘Okay okay okay’ is ‘a single stretch of talk’.

‘Okay. Okay. Okay’, on the other hand, is ‘multiple packages’.

She believes that the one is, in a way, quite different from the other. Repeating little phrases as a single lump can imply something deep and simple: that the other person’s whole course of action is problematic and should be halted.

Stivers illustrates her point with lots of snatches of conversation. Her report delves into the technical aspects of certain uses of ‘Yes yes yes’, ‘No no no’, ‘Right right right’, ‘I’ll eat ’em / I’ll eat ’em / I’ll eat ’em’, ‘a’right / a’right / a’right’, and ‘I see / I see / I see’.

Most of her examples come from English-language conversations, but Stivers says that ‘the practice has been found in Catalan, French, Hebrew, Japanese, Korean, Lao, and Russian, as well’.

Tanya Stivers is part of a small gaggle of scholars who call themselves conversation analytic researchers. Conversation analytic researchers study the anatomy and physiology of people’s jabberings. They record people talking, then have someone transcribe the recordings. Then they analyse / analyse / analyse.

Conversation is complicated stuff, despite the ease with which people yak / yak / yak together. It can be difficult for outsiders – people who are not conversation analytic researchers – to appreciate that these professionals need some unusual skills.

A taste of professionally boiled, sliced conversational analysis can seem off-putting to the casual conversationalist. Here is a not-unusual sample, written by Thomas Holtgraves, of Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana: ‘Conversation analytic researchers have demonstrated that conversationalists do appear to be sensitive to the occurrence of dispreferred markers’.

Such technical lingo can make it difficult for people who are not conversation analytic researchers to see what people who are conversation analytic researchers are talking about. This is sad, because what conversation analytic researchers talk about, mostly, is the conversations of people who are not conversation analytic researchers. And the researchers rejoice, because their research tells them that repetition is not – repeat, not – boring.

Stivers, Tanya (2004). ‘“No no no” and Other Types of Multiple Sayings in Social Interaction.’ Human Communication Research 30 (2): 260–93.

Holtgraves, Thomas (2000). ‘Preference Organization and Reply Comprehension.’ Discourse Processes 30 (2): 87–106.

Call for Submissions

If you know of any improbable research – the sort that makes you laugh and think, and that you think will make other people laugh, too – I would be delighted and grateful to hear about it.

Please email me at marca@improbable.com with an improbable subject line of your choosing.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the good editors (and in my experience, they are exactly that) who got and kept me writing for the Guardian and whose suggestions and advice and criticism have almost always been ‘spot on’ (as British people say in books) and encouraging. In order of appearance, they are Tim Radford, Will Woodward, Claire Phipps, Donald MacLeod, and Alice Wooley.

Thank you to my wife, Robin. Thanks to my parents for endowing me with tolerance and curiosity for random assortments. Thanks to my many colleagues and friends and readers (those categories blend) who together comprise Improbable Research – both the uppercase version and the larger, lowercase version – and the Ig Nobel gang. Look on the web site, www.improbable.com, and you’ll see many of their names and much of their influence.

Thanks to the three people most responsible for conjuring whatever it was they conjured that caused this book to apparate: Regula Noetzli and Caspian Dennis, ace agents; and Robin Dennis, ace editor. These Dennises, I believe, are not related to each other, except in the world of books.

Particular thanks to each of the many people who told me about things that wound up in this book. They have been kind in sharing their discoveries with me, that I might share them with you. Here are some of them: Claudio Angelo, Catherine L. Bartlett, Michael L. Begeman, John Bell, Charles Bergquist, Lisa Birk, John D. Bullough, Peter Carboni, the Chemical Heritage Foundation, Francesca Collins, Lauradel Collins, Jim Cowdery, Fuzz Crompton, Missy Cummings, Wim Crusio, Kristine Danowski, David Derbyshire, Betsy Devine, Paola Devoto, Tatiana Divens, Matthias Ehrgott, Stanley Eigen, Steve Farrar, Rose Fox, Stefanie Friedhoff, Andrea Gaddini, Martin Gardiner, Rebecca German, David Gevirtz, Tom Gill, Max Glaskin, Diego Golombek, N. Hammond, Ron Hassner, Mark Henderson, Simon Hudson, Alok Jha, Torbjörn Karfunkel, Mark Keiser, David Kessler, Erwin Kompanje, Scott Langill, Tom Lehrer, T. Leighton, Jill LePore, Alan Litsky, Julia Lunetta, Donald MacLeod, James Mahoney, William J. Maloney, G. N. Martin, Neil Martin, Les Martinsson, Maryn McKenna, Chris McManus, Fernando Merino, Rosie Mestel, Katherine Meusey, Kees Moeliker, Jean Monahan, Harold Morowitz, Gabriel Nève, Scott A. Norman, Charles Oppenheim, Eduardo B. Ottoni, Rich Palmer, Ruth Parrish, Michael Ploskonka, Bella Plouffe, Stavros Poulos, Hanne Poulsen, Gus Rancatore, James Randerson, Thomas A. Reisner, R. Roberts, Geneva Robertson, Ian Sample, Reto Schneider, M. Schreiber, Sally Shelton, Adrian Smith, Annette Smith, Andrew N. Stephens, Geri Sullivan, Frank Sutman, B. E. Swetman, Vaughn Tan, Tony Taylor, Mary Thomson, Richard Wassersug, Corky White, Amity Wilczek, Michael Wolfson, and Jan Wooten.

Extra Citations

In Brief

Al Fallouji, M. (1990). ‘Traumatic Love Bites.’ British Journal of Surgery 77: 100–1.

Buchanan, D. R., D. Lamb, and A. Seaton (1981). ‘Punk Rocker’s Lung: Pulmonary Fibrosis in a Drug Snorting Fire-Eater.’ British Medical Journal 283: 1661.

Cassaro, A., and M. Daliana (1992). ‘Impaction of an Ingested Table Fork in a Patient with a Surgically Restricted Stomach.’ New York State Journal of Medicine 92 (3): 115.

Cheng, G., Z. Xuand, and J. Xu (2005). ‘Vision of Integrated Happiness Accounting System in China.’ Acta Geographica Sinica 60 (6): 893–901.

Coolidge, Frederick L. (1999). ‘My Grandmother’s Personality: A Posthumous Evaluation.’ Journal of Clinical Geropsychology 5 (3): 215–19.

Earles, C. M., A. Morales, and W. L. Marshall (1988). ‘Penile Sufficiency: An Operational Definition.’ Journal of Urology 139 (3): 536–38.

Foley, J., and J. J. Sheuring (1966). ‘Cause of Microbial Death during Freezing in a Soft-Serve Ice Cream Freezer.’ Journal of Dairy Science 49 (8) 928–32.

Gordon, Christopher J., and Elizabeth C. White (1982). ‘Distinction Between Heating Rate and Total Heat Absorption in the Microwave-Exposed Mouse.’ Physiological Zoology 55 (3): 300–8.

Krause, D., D. Ick, and H. Treu (1981). ‘Successful Insemination Experiments with Cryopreserved Sperm from Wild Boars.’ Zuchthygiene.

Liu, Bing, Liang-Ping Ku, and Wynne Hsu (1997). ‘Discovering Interesting Holes in Data.’ Proceedings of Fifteenth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Nagoya, Japan: 930–35.

McVeigh, Brian J. (2000). ‘How Hello Kitty Commodifies the Cute, Cool, and Camp: “Consumutopia” Versus “Control” in Japan.’ Journal of Material Culture 5 (2): 225–45.

Oppenheimer, Daniel M. (2006). ‘Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly.’ Applied Cognitive Psychology 20: 139–56.

Ortmann, C., and A. DuChesne (1998). ‘A Partially Mummified Corpse with Pink Teeth and Pink Nails.’ International Journal of Legal Medicine 111: 35–37.

Pories, Walter J. (2001). ‘The Cow with Zits.’ Current Surgery 58 (1): 1.

Seiffert, H. J. (2000). ‘A Cute Characterization of Acute Triangles.’ American Mathematical Monthly 107 (5): 464.

Smith, Geoff P. (1995). ‘How High Can a Dead Cat Bounce?: Metaphor and the Hong Kong Stock Market.’ Linguistics and Language Teaching 18: 43–57.

Smith, Thomas J., Bruce E. Hillner, and Harry D. Bear (2003). ‘Taking Action on the Volume-Quality Relationship: How Long Can We Hide Our Heads in the Colostomy Bag?’ Journal of the National Cancer Institute 95 (10): 695–97.

Spears, A. S. (1994). ‘Attempted Suicide or Hitting the Nail on the Head: Case Report.’ Journal of the Florida Medical Association 81 (12): 822–23.

Stitt, W. Z., and A. Goldsmith (1995). ‘Scratch and Sniff: The Dynamic Duo.’ Archives of Dermatology 131: 997–99.

Thompson, D. G. (2001). ‘Descartes and the Gut: “I’m Pink Therefore I Am”.’ Gut, 2001) 49: 165–66.

Witts. Richard (2005). ‘I’m Waiting for the Band: Protraction and Provocation at Rock Concerts.’ Popular Music 24 (1): 147–52.

N.A. (1974). ‘The Case of the Burly Wee Man’ (published in the Archives of Environmental Health 28 (5): 297–98.

May We Recommend

Anders Barheim and Hogne Sandvik (1994). ‘Effect of Ale, Garlic, and Soured Cream on the Appetite of Leeches.’ BMJ 209: 1689.

Bollinger, S. A., S. Ross, L. Oesterhelweg, M. J. Thali, and B. P. Kneubeuhl (2009). ‘Are Full or Empty Beer Bottles Sturdier and Does Their Fracture-Threshold Suffice to Break the Human Skull?’ Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 16: 138–42.

Bolt, Michael, and Daniel C. Isaksen (2010). ‘Dogs Don’t Need Calculus.’ College Mathematics Journal 41 (1): 10–16.

Bubier, Norma E., Charles G. M. Paxton, P. Bowers, D. C. Deeming (1998). ‘Courtship Behaviour of Ostriches (Struthio camelus) Towards Humans Under Farming Conditions in Britain.’ British Poultry Science 39 (4): 477–81.

Coventry, K. R., and B. Constable (1999). ‘Physiological Arousal and Sensation-Seeking in Female Fruit Machine Gamblers.’ Addiction 94 (3): 425–30.

Griffin, John M., and Jin Xu (2009). ‘How Smart Are the Smart Guys? A Unique View from Hedge Fund Stock Holdings.’ Review of Financial Studies 22 (7): 2531–70.

Griffin, Michael J., and R. A. Hayward (1994). ‘Effects of Horizontal Whole-Body Vibration on Reading.’ Applied Ergonomics 25 (3): 165–69.

Hopton, Robert, Steph Jinks, and Tom Glossop (2010). ‘Determining the Smallest Migratory Bird Native to Britain Able to Carry a Coconut.’ Journal of Physics Special Topics 9 (1).

Krippner, Stan, Monte Ullman, and Bob Van de Castle (1973). ‘An Experiment in Dream Telepathy with “The Grateful Dead”.’ Journal of the American Society of Psychosomatic Dentistry and Medicine 20: 9–17.

Miller, Geoffrey, Joshua M. Tybur, and Brent Jordan (2007). ‘Ovulatory Cycle Effects on Tip Earnings by Lap Dancers: Economic Evidence for Human Estrus?’ Evolution and Human Behavior 28 (6): 375–81.

Nirapathpongporn, Apichart, Douglas H. Huber, and John N. Krieger (1990). ‘No-Scalpel Vasectomy at the King’s Birthday Vasectomy Festival.’ Lancet 335: 894–95.

Pennings, Timothy J. (2010). ‘Do Dogs Know Calculus?’ College Mathematics Journal 34 (3): 178–182.

Randall, Brad (2009). ‘Blood and Tissue Spatter Associated with Chainsaw Dismemberment.’ Journal of Forensic Sciences 54 (6): 1310–14.

Stephens, Richard, John Atkins, and Andrew Kingston (2009). ‘Swearing as a Response to Pain.’ Neuroreport 20: 1056–60.

Traub, Stephen J., Robert S. Hoffman, and Lewis S. Nelson (2001). ‘Pharyngeal Irritation After Eating Cooked Tarantula.’ Internet Journal of Medical Toxicology 39: 562.

US National Institute of Health (1993). ‘Fatalities Attributed to Entering Manure Waste Pits.’ Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 42 (17): 325–29.

Willan, Derek, ed. (1994). Greek Rural Postmen and Their Cancellation Numbers. N.P.: Hellenic Philatelic Society of Great Britain.

An Improbable Innovation

Bodnar, Elena N., Raphael C. Lee, and Sandra Marijan (2007). ‘Garment Device Convertible to One or More Facemasks.’ US Patent no. 7,255,627, 14 August.

Imai, Makoto, Naoki Urushihata, Hideki Tanemura, Yukinobu Tajima, Hideaki Goto, Koichiro Mizoguchi, and Junichi Murakami (2009). ‘Odor Generation Alarm and Method for Informing Unusual Situation.’ US Patent application no. 2010/0308995 A1, 9 December.

Keogh, John (2001). ‘Circular Transportation Facilitation Device.’ Australian Innovation Patent no. 2001100012, 2 August.

Li, Zhengcai (2007). ‘A Tittle Obliquity Measurer.’ International Patent application no. PCT/CN2007/003282, 6 December.

Miller, Gregg A. (1999). ‘Surgical Method and Apparatus for Implantation of a Testicular Device.’ US Patent no. 5,868,140, 9 February.

Nutting, William B. (1971). ‘Kiss Throwing Doll.’ US Patent no. 3,603,029, 7 September.

Scruggs, Donald E. (2011). ‘Edged Non-horizontal Burial Containers.’ US Patent no. 8,046,883, 1 November.

Smith, Frank J., and Donald J. Smith (1977). ‘Method of Concealing Partial Baldness.’ US Patent no. 4,022,227, 10 May.

Call For Investigators

Bax, Ad, David Max, and David Zax (1992). ‘Measurement of Long-Range 13C-13C J Couplings in a 20-kDa Protein-Peptide Complex.’ Journal of the American Chemical Society 114 (17): 6923–25.

Illustration Credits

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the many researchers and inventors whose work is illustrated in these pages, sometimes with illustrations, sometimes without.

Selected steps from ‘Method of Concealing Partial Baldness’ (p. 20) from US Patent no. 4,022,227

From ‘Garment Device Convertible to One or More Facemasks’ (p. 30) from US Patent no. 7,255,627

Height vs. distance for footballs kicked on Earth (solid line) and Mars (dashed line) (p. 44) adapted from ‘Association Football on Mars’ by Calum James Meredith, David Boulderstone, and Simon Clapton

X-ray of a road-kill green woodpecker and schematic of woodpecker at work (p. 53) from ‘A Woodpecker Hammer’ by Julian F. V. Vincent, Mehmet Necip Sahinkaya, and W. O’Shea

Geometric division of an elephant from ‘Estimation of the Total Surface Area in Indian Elephants (Elephas maximus indicus) (p. 65) by K. P. Sreekumar and G. Nirmalan

Fish’s stroke frequency vs. swimming velocity in six platypuses (p. 66) adapted from ‘Energetics of Swimming by the Platypus Ornithorhynchus anatinus’ by F. E. Fish, R. V. Baudinette, et al.

N.B. Lizardfall plummets in December adapted from ‘Arboreal Sprint Failure’ (p. 71) by William H. Schlesinger, Johannes M. H. Knops, and Thomas H. Nash

Detail from Egede’s monstrous account of 1741 and North Atlantic right whale penis of 2001 (p. 75) from ‘Cetaceans, Sex and Sea Serpents’ by C. G. M. Paxton, Erik Knatterud, and Sharon L. Hedley. Photograph reproduced by permission of the New England Aquarium, Boston, Massachusetts.

Sheep personality vs. location adapted from ‘Effects of Group Size and Personality on Social Foraging’ (p. 80) by Pablo Michelena, Angela M. Sibbald, Hans W. Erhard, and James E. McLeod

Distance between two cows during grazing phase (p. 83) adapted from ‘How are Distances Between Individuals of Grazing Cows Explained by a Statistical Model?’ by Masae Shiyomi

Figure: ‘Comparison of amount of faeces accumulated under the lavatory seats in a lavatory at the Antarctic’ (p. 96) from ‘Review of Medical Researches at the Japanese Station (Syowa Base) in the Antarctic’ by H. Yoshimura

Digestive damage to a surviving shrew humerus and surviving shrew tibio-fibula (p. 105) from ‘Human Digestive Effects on a Micromammalian Skeleton’ by Brian D. Crandall and Peter W. Stahl

How to generate a shock pressure wave for tenderizing an article of food (p. 112) from US Patent no. 3,492,688

Figure: ‘The relationship between craving, built, and the eating of chocolate bars …’ (p. 115) adapted from ‘The Development of the Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire’ by David Benton, Karen Greenfield, and Michael Morgan

The long and short of bartenders’ pours (p. 130) adapted from ‘Shape of Glass and Amount of Alcohol Poured’ by Brian Wansink and Koert van Ittersum

Fig. 1 of 13… (p. 147) adapted from US Patent no. 7,266,767

Figure: ‘Two-way interaction of number of meetings and perceived meeting effectiveness to predict job satisfaction’ (p. 156) adapted from ‘Not Another Meeting!’ by S. G. Rogelberg, D. J. Leach, P. B. Warr, and J. L. Burnfield

The patented Kiss-Throwing Doll (p. 168) from US Patent no. 3,603,029

Figure: Types of mounts, with and without mobile phone (p. 180) adapted from ‘Effects of Exposure to a Mobile Phone on Sexual Behavior in Adult Male Rabbit’ by Nader Salama, Tomoteru Kishimoto, Hiro-Omi Kanayama, and Susumu Kagawa

Changes in beard growth during a short stay on the island (p. 185) adapted from N.A., ‘Effects of Sexual Activity on Beard Growth in Man’, Nature 226 (30 May 1970): 869-70

Evidence of a huge Parisian tooth-yanker (p. 196). Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London.

Dr Bean’s twenty-year nail chart (p. 203) from ‘A Discourse on Nail Growth and Unusual Fingernails’ by William B. Bean

Number of deaths from myocardial infarction, French men vs. French women (p. 208) adapted from ‘Lower Myocardial Infarction Mortality in French Men the Day France Won the 1998 World Cup of Football’ by F. Berthier and F. Boulay

Figure: ‘A tractor backhoe using a square section clamping gripper driver to hold, revolve and press a casket into a pre-bored or augered hole’ (p. 229) from US Patent no. 8,046,883

The eponymous number of clasp knives (p. 231) from ‘Account of a Man Who Lived Ten Years After Having Swallowed a Number of Clasp-Knives, with a Description of the Appearances of the Body After Death’ by Alex. Marcet

Figure: ‘The knife cut which divides the ham into equal area portions’ (p. 236) adapted from ‘Green Eggs and Ham’ by M. J. Kaiser and S. Hossaien Cheraghi

Facial representation of financial performance (p. 242) adapted from ‘Facial Representation of Multivariate Data’ by David L. Huff, Vijay Mahajan, and William

The tittle obliquity measurer (p. 246) from International patent application no. PCT/CN2007/003282

The centre point – the intersection of common sense and the Peter Principle… (p. 250) adapted from ‘The Peter Principle Revised’ by Alessandro Pluchino, Andrea Rapisarda, and Cesare Garofalo

As feature in Perception vol. 35’s ‘Last But Not Least’ (p. 256) adapted from ‘Eye-witnesses Should Not Do Cryptic Crosswords Prior to Identity Parades’ by Michael B. Lewis

From ‘Net Trapping System for Capturing a Robber Immediately’ (p. 258) from US Patent no. 6,219,959

Underarm stab action’ demonstrated (p. 267) from ‘An Assessment of Human Performance in Stabbing’ by I. Horsfall, P. D. Prosser, C. H. Watson, and S. M. Champion

Os, sampled (p. 270) from ‘Quantification of the Shape of Handwritten Characters’ by Raymond Marquis, Matthieu Schmittbuhl, William David Mazzella, and Franco Taroni

Note from study: The label ‘Hetero’ refers to ‘heterosexual intimate relationships’… (p. 285) adapted from ‘Dude’ by Scott F. Kiesling

‘Audience members overwhelmingly agree that the man on the left is named “Tim” and the man on the right is named “Bob”’ (p. 287) from ‘Who Do You Look Like?’ by Melissa A. Lea, Robin D. Thomas, Nathan A. Lamkin, and Aaron Bell