One

Strange in the Head

In Brief

‘My Grandmother’s Personality: A Posthumous Evaluation’

by Frederick L. Coolidge (published in the Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 1999)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Thinking, to the brink of medical danger • Spotting hairy heads in theme parks • Being bored for His Majesty • Playing on, whilst being watched • Being brain damaged, for better wagering • Fingering beauty for intelligence • Heading up Brain • An Alias for body hair • Praying, to the brink of madness.

Your Mind Could Kill You

Exactly how dangerous is it to think? The question matters, because for some people it truly is dangerous – physically, life-threateningly dangerous.

This question also bears on one that’s seemingly unrelated: is it dangerous for students to use a calculator, rather than do maths in their heads?

In 1991, researchers in Osaka, Japan published a report called ‘Reflex Epilepsy Induced by Calculation Using a “Soroban”, a Japanese Traditional Calculator’. (The English word for soroban is ‘abacus’.) The report describes an unfortunate young man who ‘entered college in 1980, where he belonged to a music club and was in charge of the drums. After six months, he felt intense psychological tension during drum playing and particularly when he had to write musical scores phrase after phrase while listening to the music recorded on tape.’ The situation worsened. Writing musical scores sometimes induced generalized tonic-clonic convulsions. The man truly suffered for his music.

In his final year at university, he discovered that doing calculations on an abacus caused the same problem, with even more severity. He stopped using an abacus, and started seeing doctors.

Specialists have seen and reported other such cases.

Consider the disturbingly thought-provoking paper entitled ‘Seizures Induced by Thinking’. The report was published by A. J. Wilkins and three colleagues at the University of Essex in the Annals of Neurology in 1982. The researchers describe a man who suffered convulsions whenever he performed certain kinds of mental arithmetic. This was pure mental calculation, without the complication of an abacus or other mechanical or electronic apparatus. Mental addition seemed harmless enough for this man, and so did mental subtraction. But whenever he tried doing multiplication in his head, it triggered seizures. Division was equally a danger.

Other cases on record hint that subtraction is not always as safe as it seems, at least not for absolutely everyone. Nor is addition.

Mathematics and musical composition are not the only hazardous mental activities. A team at St Thomas’ Hospital in London documented the plight of seventeen people who must watch what they watch. For them, the act of reading can trigger seizures. Newspapers are dangerous. Books are dangerous. Perilous materials are everywhere. There are also people for whom the act of writing is dangerous.

So, in reading, in writing, in arithmetic, and in other kinds of thought, true dangers lurk. They are exceedingly rare. At least, that’s what the doctors say they think.

Wilkens, A. J., B. Zifkin, F. Andermann, and E. McGovern (1982). ‘Seizures induced by thinking.’ Annals of Neurology 11: 608–12.

Yamamoto, Junji, Isao Egawa, Shinobu Yamamoto, and Akira Shimizu (1991). ‘Reflex Epilepsy Induced by Calculation Using a “Soroban”, a Japanese Traditional Calculator.’ Epilepsia 32: 39–43.

Koutroumanidis, M., M. J. Koepp, M. P. Richardson, C. Camfield, A. Agathonikou, S. Ried, A. Papadimitriou, G. T. Plant, J. S. Duncan, and C. P. Panayiotopoulos (1998). ‘The Variants of Reading Epilepsy. A Clinical and Video-EEG Study of 17 Patients with Reading-Induced Seizures.’ Brain 121: 1409–27.

Combing Through the Data

Clarence Robbins and Marjorie Gene Robbins visited theme parks hoping to find a good, representative mix of hairy-headed strangers. They then wrote ‘Hair Length in Florida Theme Parks: An Approximation of Hair Length in the United States of America’. The study tells how Robbins and Robbins gathered their data, combed through it, and extrapolated the strands to gain a new understanding of America.

At the time of their investigation, Robbins and Robbins were the leading researchers at Clarence Robbins Technical Consulting, a think tank located in their home in Clermont, Florida. Clermont is just a short drive from four big theme parks – Epcot, Universal Studios, the Magic Kingdom, and MGM Studios. In visiting those parks, the researchers set themselves a simple, clear goal: ‘to obtain data on the percentage of persons in the US with different lengths of scalp hair’.

The goal was not so easily attained. Robbins and Robbins found it prudent to make two additional theme park visits specifically to address questions pertaining to accuracy.

The first extra visit was to ‘determine whether or not any hairstyles might interfere with or affect our estimates on free-hanging hair length’. This proved susceptible to an easy statistical adjustment.

The other visit was to ‘determine whether or not any headcovers’ – by which they meant caps, hats, and scarves – would skew the estimates. They decided, happily, that headcovers cause no such problems.

Robbins and Robbins could not, of course, ensure that their hairy-headed sample accurately represented the entire American populace. But the monograph tells how they tried: ‘In an attempt to try to determine how this population relates to the general US population, several telephone calls were made to the Walt Disney Corporation, including their Market Research Department. Those contacted refused to provide any helpful information, indicating that their data and results were proprietary.’

The Robbins–Robbins study, though technical in nature, also presents facts that may be enlightening to laypersons: ‘One woman who was observed at Epcot had hair reaching several centimeters past her buttocks. She was dressed in a skintight costume, as were two young men walking with her shortly after a Disney parade. She had curly blonde hair and appeared to be in her mid to late 20s. This woman was most likely a Disney employee, hired for her long hair, because we observed her once before in a Disney parade playing Rapunzel.’

The report, published in the Journal of Cosmetic Science, concludes with a compelling summary: ‘By observing the hair of 24,300 adults in central Florida theme parks at specified dates from January through May of 2001 and estimating hair length relative to specific anatomical positions, we conclude that about 13% of the US adult population currently has hair shoulder-length or longer, about 2.4% have hair reaching to the bottom of the shoulder blades or longer, about 0.3% have hair waist-length or longer, and only about 0.017% have hair buttocks-length or longer. Hair appreciably longer than buttock-length was not observed in this population.’

Robbins, Clarence, and Marjorie Gene Robbins (2003). ‘Scalp Hair Length. I. Hair Length in Florida Theme Parks: An Approximation of Hair Length in the United States of America.’ Journal of Cosmetic Science 54 (1): 53–62.

Truth on the Side

On which side lies the truth? It’s on the left, according to a 1993 study published in the journal Neuropsychologia. The left ear, this study says, is better than the right ear at discerning truth. Slightly better. In most people. Some of the time.

The experiment, called ‘Hemispheric Asymmetry for the Auditory Recognition of True and False Statements’, was conducted by Franco Fabbro and his team at the University of Trieste. Twenty-four men and twenty-four women each donned headphones, and then (presumably) followed these instructions: ‘In the headphones you will hear phrases pronounced by four people you don’t know. There are two types of phrase – “This is a pleasant photo” and “This is an unpleasant photo”. While they pronounced these phrases they were looking at photographs which they had previously judged to be pleasant or unpleasant. Sometimes they are telling the truth. Sometimes they are lying. After hearing a phrase you have to decide whether you think the speakers are telling the truth or a lie.’

The effect is subtle. According to the data, the left-ear truth detector is not especially good at recognizing women’s lies. It works, to the extent it works, only when a man does the lying. Even then, it correctly recognizes only sixty-three percent of the true statements as being true.

Fabbro and his colleagues were intrigued by the two cerebral hemispheres. One is thought to be more skilled than the other at handling emotions. ‘Most people undergo an increase in emotional stress when telling a lie’, the study says. The theory, too, is subtle. Fabbro and his colleagues phrase it this way: ‘Since in human cultures lying prevailingly occurs at the verbal level, it is reasonable to expect a stronger tendency to consider false that kind of information which is transmitted and processed through verbal systems. For the same token it is reasonable to expect a stronger tendency to consider true the information which is processed by non-verbal systems.’

A different experiment, conducted more than a decade earlier at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, looked for something less subtle. And found it.

Walter W. Surwillo told all in his study called ‘Ear Asymmetry in Telephone-Listening Behavior’, which was published in the journal Cortex. He, too, was curious about the powers of the left ear versus the right. Surwillo surveyed people whose jobs involve a lot of telephoning, and also people whose jobs don’t. His question: which ear do they prefer for listening on a telephone?

The results: ‘Listening with the left ear was associated with heavy use of the telephone. The most frequently given reason for listening with the left ear was that it freed the right hand for writing and dialing. This preference would appear to be motivated by convenience for although either ear is available for listening, it is easier to hold the receiver to the left than the right ear while grasping it in the left hand.’

For further elucidation of the relative power of the left and right ears, you may wish to consult a study of 203 telesales staff examining the relationship between ear preference, personality, and job performance ratings. Those who preferred a right ear headset generally rated higher in supervisors’ eyes when it came to actual performance and developmental potential compared to those staff who preferred a left ear headset.

Fabbro, F. B., B. Gran, and A. Bava (1993). ‘Hemispheric Asymmetry for the Auditory Recognition of True and False Statements.’ Neuropsychologia (31) 8: 865–70.

Surwillo, Walter W. (1981). ‘Ear Asymmetry in Telephone-Listening Behavior.’ Cortex 17 (4): 625–32.

Jackson, Chris J., Adrian Furnham, and Tony Miller (2001). ‘Moderating Effect of Ear Preference on Personality in the Prediction of Sales Performance.’ Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain, and Cognition 6 (2): 133–40.

Imperial Boredom

True, at its height, the British Empire produced magnificent heaps of wealth and power. But according to historian Jeffrey Auerbach, the empire also generated staggering amounts of boredom.

In a copiously documented report in the journal Common Knowledge, Auerbach writes: ‘Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, British imperial administrators at all levels were bored by their experience traveling and working in the service of king or queen and country. Yet in the public mind, the British empire was thrilling – full of novelty, danger, and adventure, as explorers, missionaries, and settlers sailed the globe in search of new lands, potential converts, and untold riches.’

Auerbach’s interests are not limited to boredom. An assistant professor of history at California State University, Northridge, he has published on many other subjects, among them ‘The Homogenization of Empire’, ‘The Monotony of Empire’, and the inspirationally titled ‘The Impossibility of Artistic Escape’.

The imperial boredom report is filled with telltale evidence of administrators’ boredom. Those administrators range from the soon-to-be celebrated Winston Churchill (who at age twenty-one wrote that Indian life was ‘dull and uninteresting’) to the clerk who wrote this ditty:

From ten to eleven, ate a breakfast at seven;

From eleven to noon, to begin ‘twas too soon;

From twelve to one, asked ‘What’s to be done?’

From one to two, found nothing to do;

From two to three, began to foresee

That from three to four would be a damned bore.

Auerbach complains that, for generations, ‘Scholars have by and large perpetuated [a] glamorous view of the empire, portraying imperial men either as heroic adventurers who charted new lands and carried “the white man’s burden” to the farthest reaches of the planet or as aggressors who imposed culturally bound norms and values on indigenous peoples and their ways of life.’

He says he did his research by ‘reading against the grain of published memoirs and travel logs’ and by digging into the unspectacular mutterings of private diaries and letters. His task was the more difficult, he argues, because ‘if people felt bored before the mid-eighteenth century, they did not know it’. This view of boredom, he points out, was persuasively developed by Patricia Meyer Spacks, whose 304-page book Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind, titillated thrill-starved scholars in 1995.

Auerbach is himself writing a book. It’s about imperial boredom. He will need to expand considerably upon his current study, which is twenty-three pages long and includes only seventy-six footnotes. As this book – the one you are reading – goes to press, Auerbach’s book has not yet hit the market. His website lists it as Imperial Boredom: The Banality of the British Empire, 1757–1939 (in progress).

Perhaps, though, Auerbach has already done his finest work. Here, in just forty-seven words, is his take on imperial boredom: ‘The reality simply could not live up to the expectations created by newspapers, novels, travel books, and propaganda. As a consequence, notwithstanding some famous exceptions, nineteenth-century colonial officials were deflated by the dreariness of their imperial lives, desperate to ignore or escape the empire they had built.’

Auerbach, Jeffrey (2005). ‘Imperial Boredom.’ Common Knowledge 11 (2): 283–305.

28 Straight Hours of Vexations

German and Austrian researchers analysed what happened to pianist Armin Fuchs when he spent more than a full day playing over and over again, nonstop, an oddly named piece of music by a French composer. They also analysed what happened to the music. This was a tour de force of artistic and neurological repetition.

The research team – Christine Kohlmetz, Reinhard Kopiez, and Marc Bangert of the Hanover University of Music and Drama, and Werner Goebl and Eckart Altenmüller of the Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence, in Vienna – published a pair of monographs in 2003 describing what they measured in the pianist.

The study titles, like the performance, are lengthy. One, in the journal Psychology of Music, includes the phrase ‘Electrocortical Activity in a Pianist Playing “Vexations” by Erik Satie Continuously for 28 Hours’. When Satie composed the piece in 1893, he added an instruction that the performer should: ‘play this motif 840 times in succession’.

Twenty-first-century researchers Kohlmetz, Kopiez, Bangert, Goebl, and Altenmüller explicitly question whether nineteenth-century composer Satie ‘was aware of the effect his work might have on a pianist, especially with regard to his or her consciousness and motor function’.

Do the maths and you’ll see that Fuchs, the intrepid piano player, averaged thirty performances per hour. That’s a lot of ‘Vexations’, in two-minute-long chunks.

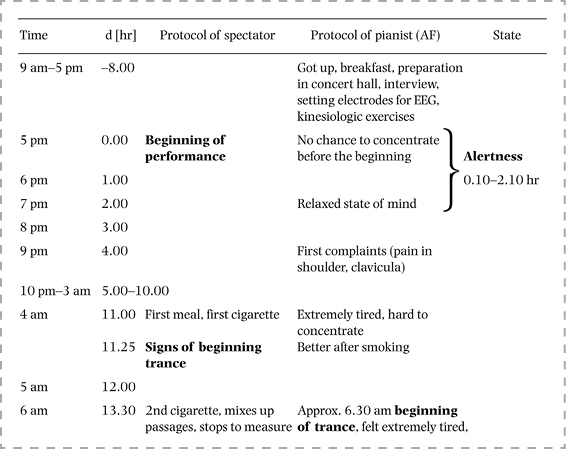

Detail from table: ‘Event protocol of the performance recorded by an observer and retrospectively by the pianist’

By affixing wires to Fuchs’s head and using an electroencephalograph (EEG) to continuously monitor gross electrical activity in his brain, the researchers discovered that ‘the pianist experienced different states of consciousness throughout the performance ranging from alertness to trance and drowsiness’.

Fuchs’s playing grew inconsistent during the periods of drowsiness. But when alert, the man was a model of consistency. ‘Most importantly’, says the study, ‘whilst in deep trance, which included effects such as time-shortening, altered perception and characteristic changes in the EEG, the pianist managed not only to keep on playing but also to maintain a constant tempo, hence executing complex motor schemes at a high level of performance.’ (For a video of the performance in progress, visit http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=km9GiejF5OQ.)

The second study, published in the Journal of New Music Research, gives a much finer-grained ‘tempo and loudness analysis’. It boasts that ‘non-linear methods revealed that changes in loudness and tempo are of a highly complex nature, and both parameters unfold in an 18-dimensional space. This has never before been demonstrated in performance research.’

‘Vexations’ is not one of Erik Satie’s most beloved compositions, not yet anyway. Although brief (when played, contrary to instructions, just a single time), it meanders along in a way that’s neither quick nor catchy.

But Satie pioneered something of value – the technique (‘play this motif 840 times’) that the music business would refine many years later, with significant payoff. Radio disc jockeys demonstrated in the 1950s that, by persistently, diligently repeating a song, they could ensconce it into the minds of many listeners, who would ever after believe it to be one of their favourite tunes.

Kohlmetz, Christine, Reinhard Kopiez, and Eckart Altenmüller (2003). ‘Stability of Motor Programs during a State of Meditation: Electrocortical Activity in a Pianist Playing “Vexations” by Erik Satie Continuously for 28 Hours.’ Psychology of Music 31 (2): 173–86.

Kopiez, Reinhard, Marc Bangert, Werner Goebl, and Eckart Altenmüller (2003). ‘Tempo and Loudness Analysis of a Continuous 28-Hour Performance of Erik Satie’s Composition “Vexations”.’ Journal of New Music Research 32 (3): 243–58.

The Mind of the Waiter

Buenos Aires boasts impressive waiters, whose minds are worth studying, according to the paper ‘Strategies of Buenos Aires Waiters to Enhance Memory Capacity in a Real-Life Setting’, published in the journal Behavioural Neurology. ‘Typical Buenos Aires senior waiters memorize all the orders from respective clients and take the orders without written support of as many as ten persons per table’, it explains. ‘They also deliver the order to each and every one of the customers who ordered it without asking or checking.’

And most of the time, they get it right.

How do they manage it? Researchers Tristan Bekinschtein, Julian Cardozo, and Facundo Manes ran an experiment to find out. The three are based variously at the Institute of Cognitive Neurology and at Favaloro University, both in Buenos Aires, and at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit of the University of Cambridge.

Eight customers sat around a table and ordered drinks. When the waiter returned with the beverages, the scientists tallied up how many were served to the people who had ordered them, and how many were mistakenly delivered to someone else. All the waiters performed admirably.

The customers later ordered more drinks, then switched seats before the waiter returned. This produced dreary results. The scientists tried this on nine waiters, only one of whom consistently delivered drinks to the right people.

Interviewed afterwards, the waiters explained that they generally paid attention to customers’ locations, faces, and clothing. They also disclosed a tiny trick of the trade. They ‘did not pay attention to any customer after taking a table’s order, as if they were protecting the memory formation in the path from the table to the bartender or kitchen’.

In preparing their study, Bekinschtein, Cardozo, and Manes discovered a published account of a most remarkable waiter (they do not specify, though, whether he was Argentinian). This man had trained himself to almost Olympian awesomeness in the delivery of food. He ‘could recall as many as 20 dinner orders, categorize the food (meat or starch) and link it to the location in the table. He also used acronyms and words to encode salad dressing and visualized cooking temperature for each customer’s meat and linked it to the position on the table.’

The Buenos Aires waiters, in contrast, ‘reported systematically that they have not thought of any particular strategy and that their great ability comes only with time and practice’. True or not, this answer accords with their profession’s famed tradition of haughty disdain for theory.

The best waiter – the one who delivered drinks correctly even when customers had swapped seats – claimed that, unlike his colleagues, he ignored where customers sat, and paid attention only to their looks. His professional experience, he said, ‘had been mostly in cocktail parties for 10 years, where people tend to change their position in the room; only in the last three years he had been working in the restaurant’.

Bekinschtein, Tristan A., Julian Cardozo, and Facundo F. Manes. ‘Strategies of Buenos Aires Waiters to Enhance Memory Capacity in a Real-Life Setting.’ Behavioural Neurology 20: 65–70.

Gambling with Brain Damage

Brain damage can sometimes give gamblers a winning edge, an American study suggests. The researchers take a flier at explaining how and why certain brain lesions might, in some circumstances, help a person triumph over others or over adversity.

The study, published in the journal Psychological Science, renders its tantalizing, juicy question into lofty academese. The five co-authors, led by Baba Shiv, a marketing professor at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, ask ‘Can dysfunction in neural systems subserving emotion lead, under certain circumstances, to more advantageous decisions?’

The team experimented with people who had abnormalities in particular brain regions – the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the right insular or somatosensory cortex. Medically, abnormalities in these areas can signal that something is amiss in how the person handles emotions.

Each brain-damaged person got a wad of play money, and instructions to gamble on twenty rounds of coin tossing (heads-you-win/tails-you-lose, with some added twists). Other people, who had no such brain lesions, got the same amount of money, and the same gambling instructions.

The brain-damaged gamblers pretty consistently ended up with more money than their healthier-brained competitors. The researchers speculate that when ‘normal’ gamblers encounter a run of unhappy coin-toss results, they get discouraged and become cautious – perhaps too cautious. Not so the people with brain-lesion-induced emotional dysfunction. Encountering a run of bad luck, they plunge on, undaunted. And then enjoy a relatively handsome payoff. At least sometimes.

The study notes that this brain damage side-benefit might occasionally even save someone’s life. They cite the case of a man with ventromedial prefrontal damage who was driving under hazardous road conditions: ‘When other drivers reached an icy patch, they hit their brakes in panic, causing their vehicles to skid out of control, but the patient crossed the icy patch unperturbed, gently pulling away from a tailspin and driving ahead safely. The patient remembered the fact that not hitting the brakes was the appropriate behavior, and his lack of fear allowed him to perform optimally.’

Lead author Baba Shiv has an eye for nonstandard ways of exploring the weird morass that is human behaviour. He sometimes teaches a course called ‘The Frinky Science of the Mind’. And in 2008, he and three colleagues were awarded an Ig Nobel Prize for demonstrating that expensive fake medicine is more effective than cheap fake medicine.

Shiv, Baba, George Loewenstein, Antoine Bechara, Hanna Damasio, and Antonio R. Damasio (2005). ‘Investment Behavior and the Negative Side of Emotion.’ Psychological Science 16 (6): 435–39.

Heels Give Rise to Schizophrenia

Do shoes cause schizophrenia? Jarl Flensmark of Malmo, Sweden, wants to know, and in a recent paper in the journal Medical Hypotheses, he explains why.

‘Heeled footwear’, he writes, ‘began to be used more than 1000 years ago, and led to the occurrence of the first cases of schizophrenia.... Industrialization of shoe production increased schizophrenia prevalence. Mechanization of the production started in Massachusetts, spread from there to England and Germany, and then to the rest of Western Europe. A remarkable increase in schizophrenia prevalence followed the same pattern.’

The story, if accurate and true, is disturbing. Flensmark sketches the details.

‘The oldest depiction of a heeled shoe comes from Mesopotamia, and in this part of the world we also find the first institutions making provisions for mental disorders,’ he writes. ‘In the beginning schizophrenia appears to be more common in the upper classes. Possible early victims were King Richard II and Henry VI of England, his grandfather Charles VI of France, his mother Jeanne de Bourbon, and his uncle Louis II de Bourbon, Erik XIV of Sweden, Juana of Castile [and] her grandmother Isabella of Portugal.’ All of these individuals are either known or suspected of wearing heeled shoes.

He cites evidence from other parts of the world, too – Turkey, Taiwan, the Balkans, Ireland, Italy, Ghana, Greenland, the Caribbean, and elsewhere.

‘Probably the upper classes began using heeled footwear earlier than the lower classes,’ Flensmark points out. He then cites studies from India and elsewhere, which seem to confirm that ‘schizophrenia first affects the upper classes’.

From these two streams of evidence – the rise of heels and the increase in documented cases of what may have been schizophrenia, Flensmark divines a strong connection. He modestly implies that he is not the first to do so. In the year 1740, he writes, ‘the Danish-French anatomist Jakob Winslow warned against the wearing of heeled shoes, expecting it to be the cause of certain infirmities which appear not to have any relation to it’.

Flensmark boils the matter into a damning statement: ‘After heeled shoes is [sic] introduced into a population the first cases of schizophrenia appear and then the increase in prevalence of schizophrenia follows the increase in use of heeled shoes with some delay.’

‘I have,’ he continues, ‘not been able to find any contradictory data.’

Lest critics dismiss this as mere hand-waving or foot-tapping, Flensmark explains, biomedically, how the one probably causes the other: ‘During walking synchronised stimuli from mechanoreceptors in the lower extremities increase activity in cerebellothalamo-cortico-cerebellar loops through their action on NMDA-receptors. Using heeled shoes leads to weaker stimulation of the loops. Reduced cortical activity changes dopaminergic which involves the basal gangliathalamo-cortical-nigro-basal ganglia loops.’

One could conclude that the medical establishment enjoys Flensmark’s discovery. Virtually no one has stepped up to dispute it.

Flensmark, Jarl (2004). ‘Is There an Association Between the Use of Heeled Footwear and Schizophrenia?’ Medical Hypotheses 63 (4): 740–47.

Pretty, Clever

Are beautiful people more intelligent than the rest of us? Satoshi Kanazawa and Jody Kovar think so. In their seventeen-page study ‘Why Beautiful People Are More Intelligent’, they explain bluntly: ‘Individuals perceive physically attractive others to be more intelligent than physically unattractive others. While most researchers dismiss this perception as a “bias” or “stereotype”, we contend that individuals have this perception because beautiful people indeed are more intelligent.’

Kanazawa, a reader in management and research methodology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, has become a brainy specialist on beauty: he entitled a subsequent study ‘Beautiful Parents Have More Daughters’. Kovar is affiliated with Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

The pair of them apply detective skills and high intellect to some common beliefs: ‘Critics have noted that people have the opposite stereotype that extremely attractive women are unintelligent. We do not believe such a stereotype exists, however. We instead believe that the stereotype is that blonde women and women with large breasts are unintelligent, both of which, just like the stereotype that beautiful people are intelligent, may statistically be true.’

Kanazawa and Kovar don’t merely say these things. They back them up. The volume of their evidence, if not the evidence itself, is overwhelming. Nearly all of it comes from studies – lots of them – done by other people. Among the earlier discoveries:

QUOTE: Middle-class girls ... have higher IQs and are physically more attractive than working-class girls.

QUOTE: More beautiful children and adults of both sexes have greater intelligence (and thus) the maxim ‘beauty is skin deep’ is a ‘myth’.

QUOTE: Physical attractiveness has a significant positive effect on family income, personal income and education.

Yet, for all this, there is still hope for the physically bland. Kanazawa and Kovar explain there’s a good possibility that any particular individual is not a dope: ‘Our contention that beautiful people are more intelligent is purely scientific (logical and empirical); it is not a prescription for how to treat or judge others.... At the same time, our theory is probabilistic, not deterministic, and the available evidence suggests that the empirical correlation between physical attractiveness and intelligence ... is modest at best. Thus, any attempt to infer people’s intelligence and competence from their physical appearance, in lieu of a standardized IQ test, would be highly inefficient.’

At the very end of their report, the two scientists suggest that beautiful people are more than just clever. The chain of logic, and its ultimate conclusions, are provocative:

- Aggressive men are the most likely to achieve high status and to mate with beautiful babes;

- Aggressive men are the most likely to have aggressive children, and beautiful babes are the most likely to have beautiful babies.

Add these together, Kanazawa and Kovar say, and you must conclude that, compared to everyone else, ‘beautiful people are more aggressive’.

Kanazawa, Satoshi, and Jody L. Kovar (2004). ‘Why Beautiful People Are More Intelligent.’ Intelligence 32: 227–43.

Kanazawa, Satoshi (2007). ‘Beautiful Parents Have More Daughters: A Further Implication of the Generalized Trivers-Willard Hypothesis (gTWH).’ Journal of Theoretical Biology 244 (1): 133–40.

Brain on Head in Brain

Russell Brain – who was also Lord Brain, Baron Brain of Eynsham – was editor of the journal Brain. In 2011, the journal Brain celebrated the golden jubilee of the publication of Dr Brain’s essay ‘Henry Head: A Man and His Ideas’. Head preceded Brain (the man) as head (which is to say, editor) of the journal (the name of which, I note again for clarity, is: Brain).

Head headed Brain from 1905 until 1923. Brain became head in 1954, dying in office in 1967. No other editors in the journal’s long history (it was founded in 1879) could or did boast surnames that so stunningly announced their obsession, profession, and place of employ. One of Dr Brain’s final articles, in 1963, is called ‘Some Reflections on Brain and Mind’.

Dr Head wrote many monographs, some quite lengthy, for Brain. The first, a 135-page behemoth, appeared in 1893, long before he became editor. In it, Dr Head gives special thanks to a Dr Buzzard, citing Dr Buzzard’s generosity, the nature of which is not specified.

Reading Dr Brain’s Brain tribute and other material about Dr Head, one gets the strong impression that Head had a big head, and that it was stuffed full of knowledge, which Dr Head was not shy about sharing. Brain writes that ‘Some men ... feel impelled to impart information to others. Head was one of those.’

Brain then quotes Professor H. M. Turnbull as saying: ‘I had the good fortune when first going to the hospital to meet daily in the mornings on the steam engine underground railway Dr Henry Head. He ... kindly taught me throughout our journeys about physical signs, much to the annoyance of our fellow travellers; indeed in his characteristic keenness he spoke so loudly that as we walked to the hospital from St. Mary’s station people on the other side of the wide Whitechapel Road would turn to look at us.’

Brain says that Head ‘would illustrate his lectures by himself reproducing the involuntary movements or postures produced by nervous disease, and “Henry Head doing gaits” was a perennial attraction’.

In 1904, at the age of forty-two, Head married a headmistress – Ruth Mayhew of Brighton High School for girls. Brain assures us that she was ‘a fit companion for him in intelligence’.

Brain, though respectful of Head, suggests that his predecessor was over-brainy: ‘He had many ideas: he bubbled over with them, and perhaps he was sometimes too ready to convince himself of their truth.’

Brain, Russell (1961). ‘Henry Head: The Man and His Ideas.’ Brain 84 (4): 561–66.

–– (1963). ‘Some Reflections on Brain and Mind.’ Brain 86 (3): 381–402.

Head, Henry (1893). ‘On Disturbances of Sensation with Especial Reference to the Pain of Visceral Disease.’ Brain 16 (1-2): 1–133.

–– (1923). ‘Speech and Cerebral Localization.’ Brain 46 (4): 355–528.

Rivers, W. H. R., and Henry Head (1908). ‘A Human Experiment in Nerve Division.’ Brain 31 (3): 323–450.

Hair on Heads with Brains

Henry Head is not the only outstanding head in science. The Luxuriant Flowing Hair Club for Scientists is, as the name implies, a club for scientists who have luxuriant flowing hair. LFHCfS, as it is known unpronounceably to its members and their admirers, was founded in early 2001. Anyone can join, provided only that she or he is a scientist and has luxuriant flowing hair. And is proud of it.

The ‘proud’ part is important. The club is not for the morbidly shy, people-aversive scientist of stereotype and legend. Every LFHCfS member’s hair is on display on the club’s website, at:

http://www.improbable.com/projects/hair/hair-club-top.html.

LFHCfS was founded by admirers of the famously curly mane of psychologist Steven Pinker. Pinker, then a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and now head of the psychology department at Harvard, enlisted as the first member. He proudly lists the club on his academic web page.

The membership ranks now include mathematicians, astronomers, linguists, organic chemists, computer researchers, immunologists, geneticists, physicists, neuroscientists, three sisters, a married couple, and other men and women of science, of both sexes and all hair colours and many hairstyles. There is even a real rock star, Italian chemist Piero Paravidino, a guitar player for the heavy metal band Mesmerize and co-author of the paper ‘Synthesis of Medium-Sized N-Heterocycles Through RCM of Fischer-Type Hydrazino Carbene Complexes’. Paravidino was named 2002 LFHCfS Man of the Year, beating out fellow LFHCfS member and fellow rock star, the astronomer Brian May of Queen.

Call for Members

Since the founding of the LFHCfS, scientists who once had long hair – but who no longer have hair – wrote asking if they could still be recognized, in some way. Thus was formed the LFHCfS’s two sibling clubs: the Luxuriant Former Hair Club for Scientists, and the Luxuriant Facial Hair Club for Scientists. The members of all three clubs share a quality of extremeness. Each member has extremely good hair, or extremely none.

To propose yourself for membership, please send by email:

- A photograph that clearly provides evidence of (1) luxuriant, flowing head of hair; (2) luxuriant, flowing face of hair; or (3) luxuriant head of former hair.

- A current curriculum vitae outlining your credentials as a scientist.

- A pithy statement regarding your qualifications, both hirsute and scholarly.

You may nominate someone other than yourself, provided that the person meets the relevant membership qualifications and that you have first obtained that person’s enthusiastic consent.

Send to marca@improbable.com with the subject line:

LUXURIANT HAIR CLUB

Dr Alias, Hair Man

If a hairy man becomes insatiably curious about what it means to have all that hair, he may well run across the work of Dr A. G. Alias. Yes, that is his name.

Alias is an expert on certain aspects and implications of the hairiness of men. He has taken a special interest in hairy military leaders, hairy intelligentsia, low-ranked hairy boxers, and Marlon Brando. Alias has offered this shorthand version of his views: ‘I am fairly certain that the vast majority of hairy/hirsute men, compared to the respective “much less” hirsute men of the same race and ethnic group, are strikingly more intelligent and/or educated, but only from a statistical point of view.’

Male hairiness enjoys a complex and often unclear relationship with intelligence and behaviour. Alias, who is based at the Chester Mental Health Center in Chester, Illinois, has tried to tease out a few of the many subtleties.

Alias attracted attention in 1996 when he presented a research paper called ‘A Statistical Association Between Liberal Body Hair Growth and Intelligence’ at the Eighth Congress of the Association of European Psychiatrists, held in London. He reported that hairiness is common among successful male academics, engineers, and physicians – and also among the men who join Mensa, the social club for high-scoring intelligence-test takers.

This was just a year after Alias had published a paper titled ‘Top Ranked Boxers Are Less Hirsute Than Lower Level Boxers’. In it, he discusses mesomorphs – big-boned, muscular men. Alias carefully analysed 380 drawings in William Sheldon’s book Atlas of Men. This was to gain a general understanding of whether big brutes have lots of body hair. Alias then carefully examined Harry Mullen’s tome, Great Book of Boxing, in which ‘body hair-revealing pictures are printed of 49 top-ranked, white heavyweight boxers, 15 of whom became world champions’. Alias concluded that, as a rule, champions were less hairy than non-champions. However, he cautions that the difference is not statistically significant.

Alias did not limit his research to white pugilists in dusty books; he also looked at black boxers who appeared on television. He reports that ‘around 35% of the black boxers appear to be more hirsute than any of the 16 black boxers featured in [the book] All-Time Greats of Boxing: Johnson, Louis, Walcott, Patterson, Liston, Ali, Frazier, Holmes, Tyson, M. Spinks, Robinson, Hagler, Armstrong, Hearns, Leonard, and Saddler. Archie Moore, Ezzard Charles, Mike Weaver, Tony Tubbs, Iran Ian Barkley, and Lennox Lewis, who were conspicuously hirsute, heavyweight champions, were less than outstanding.’

That same year, 1995, Alias also released a paper called ‘Non-Pathological Associational Loosening of Marlon Brando: A Sign of Hypoarousal?’ Biographers of the late actor can plumb it for unexpected insights.

Alias, A. G. (1996) ‘A Statistical Association Between Liberal Body Hair Growth and Intelligence.’ Presented at the Eighth Congress of the Association of European Psychiatrists, London, UK, 12 July.

–– (1995). ‘Top Ranked Boxers Are Less Hirsute Than Lower Level Boxers: An Example For the Importance of 5-Alpha-Reductase?’ Biological Psychiatry 37 (9): 612–13.

–– (1995). ‘Non-Pathological Associational Loosening of Marlon Brando: A Sign of Hypoarousal?’ Biological Psychiatry 37 (9): 613.

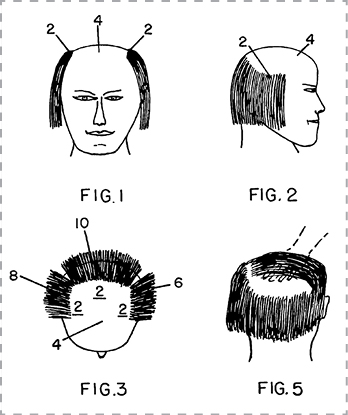

An Improbable Innovation

‘Method of Concealing Partial Baldness’

a/k/a ‘the comb-over’ by Frank J. Smith and Donald J. Smith (US Patent no. 4,022,227, granted 1977 and honoured with the 2004 Ig Nobel Prize in engineering)

Selected steps from ‘Method of Concealing Partial Baldness’

Baldly Accountable

It’s your own fault if you go bald, or if you lose your memory, or both. That’s in theory. The theory is championed by Armando José Yáñez Soler, of Elda Alicante, Spain. The town of Elda Alicante, until now, has been best known as the home of the Museo del Calzado (the Museum of Footwear), but if Yáñez’s theory is correct, his fame could eventually surpass that of the museum.

Yáñez published details of his research in the journal Medical Hypotheses. ‘The human being has evolved to become a naked monkey’, he writes, but ‘there is no apparent reason to continue the evolutionary process up to becoming a bald monkey.’ Common baldness ‘is a degenerative process derived from certain inadequate cultural practices, such as excessive hair cutting or certain types of haircuts’.

The process is roughly akin, in his view, to the coming of Alzheimer’s disease. ‘It is generally accepted’, he notes, citing a small study that appeared in the journal Neurology in 2001, ‘that loss of memory in people over 60 years of age is mainly due to ... certain behaviours of the individual.’

Yáñez is fascinated by sebum, the oily secretion produced by tiny glands in the regions of skin where hair is produced. The sebum flows around and through the hair. If this gunk builds up, says Yáñez, there ensues a cascade of physiological events that lead to baldness.

Combing, brushing, touching, or massaging one’s hair helps keep the sebum flowing out of the scalp. Sleeping with one’s head on a good, absorbent pillow sops it up. Yáñez is almost lyrical in explaining the rise and meanderings of the sebum and the attraction of pillows.

Pillows are just the half of it. Luxuriant, flowing hair is the other half. Yáñez explains that sebum can move out and along the lengthy surface of each hair and so eventually ooze its way to a pillow or a hairbrush or some other absorbent, sebum-sucking surface. Somehow, short hair doesn’t cut it.

Yáñez says his theory explains why baldness is more common in men than in women. ‘Nature provides both sexes with the capacity to have long hair’, he points out. And people with thick or curly hair have especially good sebum-elimination. ‘This explains why certain ethnicities or cultures such as Native Americans, Rastafaris, Gypsies, etc. do not suffer from common baldness.’ Furthermore, ‘many people affected by common baldness have noted that they started to suffer from it during military service.... The difference in hair length is the key. Military people, skinheads and others wear their hair short and therefore they can induce problems with sebum flow.’

Yáñez says he is ‘aware that this thought-provoking theory will give rise [to] a lot of skepticism’.

Yáñez Soler, Armando José (2004). ‘Cultural Evolution as a Possible Triggering or Causative Factor of Common Baldness.’ Medical Hypotheses 62 (6): 980–85.

Scarmeas, G. Levy, M.-X. Tang, J. Manly, and Y. Stern (2001). ‘Influence of leisure activity on the incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease.’ Neurology 57: 2236–42.

A Hole in the Head

Holes seem simple enough, until you examine them closely. Marco Bertamini, of the University of Liverpool, and Camilla Croucher, of the University of Cambridge, peered at one particular aspect. Their study, called ‘The Shape of Holes’, appeared in the journal Cognition. In it, they say: ‘We discuss the many interesting aspects of holes as a subject of study in different disciplines, and predict that much insight especially about shape will continue to come from holes.’

‘The Shape of Holes’ is a more specialized report than its title implies. Its central question deals with how we see and understand edges: do the contours of a hole belong to the hole, or to the surrounding object? Psychologists, philosophers, artists, and, recently, also computer scientists have wrestled with this and with each other for the better part of a century.

Almost certainly you have played with the black-and-white drawing made famous by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin. That’s the drawing in which you can choose to see either two faces or a vase – but not both at the same time. Look at that drawing again now, paying attention to the border between black and white, and you will see the nature of this hole question.

Bertamini and Croucher had volunteers look at line drawings that include particular kinks and bends. The goal: to better understand how we use such details to perceive particular shapes. The result: Bertamini and Croucher say that, to human eyes, the edges of a hole are not themselves part of the hole.

There is a rich, deep history of people looking into holes. Everyone, it appears, is aware of the oddity of the enterprise. In 1970, the Australasian Journal of Philosophy published an instant classic of hole scholarship. Written by Princeton University philosopher David Kellogg Lewis and his wife, Stephanie, it bears the simple title ‘Holes’. ‘Holes’ has been described as a ‘whimsical dialogue debating the ontological nature of holes’.

Recently, Flip Phillips, J. Farley Norman, and Heather Ross explored holes by using twelve sweet potatoes. They conducted their experiment at Western Kentucky University.

This project required careful preparation. The team cast silhouettes of the sweet potatoes on to a projection screen, photographed the silhouettes with a digital camera, transferred the digitized pictures to a Macintosh computer, and then fed the data to a laser printer. The result: sheets of paper imprinted with potato silhouettes. The scientists then recruited volunteers. They asked the volunteers to copy each potato silhouette to an adjacent blank area, paying special attention to the dents and protuberances of each potato-shape. The results confirm an old theory that dents and nubs play a big part in how we recognize shapes.

In theory, this patches a gap in our understanding of holes and other shapes: at the edges, it’s the kinks – not the long smooth stretches – that matter most.

Bertamini, Marco, and Camilla J. Croucher (2003). ‘The Shape of Holes.’ Cognition 87 (1): 33–54.

Lewis, David Kellogg, and Stephanie R. Lewis (1970). ‘Holes.’ Australasian Journal of Philosophy 48: 206-12; reprinted in Lewis, D. K. (1983). Philosophical Papers, vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 3–9.

Norman, J. F., F. Phillips, and H. E. Ross (2001). ‘Information Concentration Along the Boundary Contours of Naturally Shaped Solid Objects.’ Perception 30: 1285–94.

Colour Preference in the Insane

In the summer of 1931, Siegfried E. Katz of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Hospital published a study in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology called ‘Color Preference in the Insane’. Assisted by a Dr Cheney, Katz tested 134 hospitalized mental patients, asking them about their favourite colours. For simplicity’s sake, he limited the testing to six colours: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. No black. No white. No shades of grey.

‘These colors’, he wrote, ‘rectangular in shape, one and one-half inches square, cut from Bradley colored papers were pasted in two rows on a gray cardboard. They were three inches apart. The colors were numbered haphazardly and the number of each color placed above it. The cardboard was presented to the patient and he was asked to place his finger on the number of the color he liked best. After he had made the choice he was asked in a similar manner for the next best color, and so on.’

Some of the patients ‘cooperated well’, and made six choices. Others, Katz reported, ‘quickly lost interest and made only one, two or three’.

- Blue was the most popular colour. Men, in the aggregate, then favoured green, but women patients were divided on green, red, or violet as a second choice.

- Patients who had resided in the hospital for three or more years were slightly less emphatic about blue. Katz says that these long-term guests were ‘those with most marked mental deterioration’. Their preference, as a group, shifted somewhat towards green and yellow. Those of longest tenure, though few in number, had a slightly elevated liking for orange.

- The report is packed with titbits that beg, even now, for further analysis:

- Blue was given ‘first preference’ by thirty-eight percent of schizophrenics and manic depressives, versus forty-two percent of other patients.

- Green was first choice among sixteen percent of schizophrenics, nine percent of manic depressives, and thirteen percent of other patients.

- Red was first choice for sixteen percent of manic depressives, twelve percent of schizophrenics, and fifteen percent of other patients; it was the second choice of twenty-two percent of manic depressives, eighteen percent of schizophrenics, and thirteen percent of other patients.

- Orange and yellow gained the highest ‘best liked’ rating among manic depressives; green among schizophrenics, and violet among other patients.

Katz foresaw practical applications for his research. He suggested that ‘in the furnishings of living quarters the selection of colors pleasing to special groups of patients might be worth consideration’.

Consciously or not, hospital staff seem to have followed Dr Katz’s insights in fashioning their own, personal, at-work appearance. The evocatively named Bragard Medical Uniforms, a New York firm founded in 1933, now publishes a list of the most popular uniform colours. The list currently is topped by, in order: royal blue; dark grey (which, alas, Katz excluded from his survey); dark green; and red.

Katz, Siegfried E. (1931). ‘Color Preference in the Insane.’ Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 26 (2): 203–11.

May We Recommend

‘An Experiment in Dream Telepathy with “The Grateful Dead”’

by Stan Krippner, Monte Ullman, and Bob Van de Castle (published in the Journal of the American Society of Psychosomatic Dentistry and Medicine, 1973)

Neurological Damage from Praying

He who prays fervently courts danger – neurological danger.

This stark fact has only recently been reported to the public, in a study published by five neurologists at Christian-Albrechts-University in Kiel. But fear not – the risk for any particular individual is low. In the recorded history of the world, the physicians try to assure us, this is probably the very first case.

Perhaps to avoid inciting jitters among the devout, perhaps due to worries about inter-cultural tensions, or perhaps merely through professional tradition, the doctors couch their tale in dry, medico-lingo-laced language: ‘We report on an unusual presentation of a task-specific focal oromandibular dystonia in a 47-year-old man of Turkish descent. His speech was affected exclusively while reciting Islamic prayers in Arabic language, which he otherwise did not speak.’

The problem – involuntary jaw-muscle twitching – had been cropping up for two years. It occurred only when the man recited the Arabic prayers he had been praying since childhood, never at other times. It happened whether he said the prayers loud and fast, or just muttered them slowly. It would cease right after he finished praying. It never happened when he spoke in German or in Turkish. An extensive battery of tests showed him to be otherwise in good neurological, muscular, and dental health.

The doctors came up with a simple, fairly effective fix: they had the man touch himself lightly on the jaw. Usually, this would interrupt the spooky jaw gyrations.

This general kind of problem is called ‘focal dystonia’. It’s the involuntary fluttering of muscles that one ordinarily controls masterfully. It arises, somewhat mysteriously, in a few extraordinarily unlucky people who perform ‘a highly stereotyped and frequently repeated motor task’. It’s what happens in writer’s cramp, and in the eyelid twitching known as blepharospasm, and very occasionally in certain specialized professions. Doctors have seen it in pianists, tailors, and assembly-line workers. But never before in someone whose repetitive action consisted only of saying prayers.

The doctors, Tihomir Ilic, Monika Pötter, Iris Holler, Günther Deuschl, and Jens Volkmann, appear to have been surprised – and possibly a bit delighted. They bestowed upon this condition the name ‘praying-induced oromandibular dystonia’.

And digging through medical histories, they did find one earlier case that seems truly analogous. It was recorded in England in the early 1990s. The doctors (N. J. Scolding of London and four colleagues) involved in the case later published an account. ‘A 33-year-old right-handed agricultural auctioneer first noticed involuntary deviation of his jaw to the right developing while auctioneering’, they wrote. ‘Further attempts to conduct auctions met with an inevitable recurrence of his symptoms, usually after 2 to 3 minutes of speaking, and eventually it was necessary for him to move to a clerical job.’

Those doctors, like their later German counterparts, suffered the involuntary fluttering of heart and mind that is triggered by the beckoning finger of fame. They concocted a new piece of medical jargon. Thus did the term ‘auctioneer’s jaw’ enter medical literature.

Ilic, Tihomir V., Monika Pötter, Iris Holler, Günther Deuschl, and Jens Volkmann (2005). ‘Praying-Induced Oromandibular Dystonia.’ Movement Disorders 20 (3): 385–86.

Scolding, N. J., S. M. Smith, S. Sturman, G. B. Brookes, and A. J. Lees (1995). ‘Auctioneer’s Jaw: A Case of Occupational Oromandibular Hemidystonia.’ Movement Disorders 10 (4): 508v9.