Five

Eat, Think, and Be Merry

May We Recommend

‘Effect of Ale, Garlic, and Soured Cream on the Appetite of Leeches’

by Anders Barheim and Hogne Sandvik (published in BMJ, 1994, and honoured with the 1996 Ig Nobel Prize in biology)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Gut rumbling for shrinks • The tasting of the shrew • Taste-testing water, with rats • Eating eggs, eggs, eggs, and then some • How and why to explode meat • Tasty pet food • The Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire • Wondering about whisky and candles • Standard glops of food • Teabags • The frailty of bunnies

Your Gut Says ...

Some psychoanalysts can find meaning in the most ordinary-seeming bits of your life. Some discern it even in your intestinal rumblings. There’s a technical name for those digestive sounds: borborygmi. Several published studies tell how to interpret people’s gut feelings – how to translate those borborygmi into common everyday words.

In 1984, Christian Müller of Hôpital de Cery in Prilly, Switzerland, published a report called ‘New Observations on Body Organ Language’ in the journal Psychotherapy and Psychosomics. Müller paraphrases a 1918 essay, by someone named Willener, which ‘concludes that the phenomenon generally known as borborygmi must be regarded as cryptogrammatically encoded body signals that could be interpreted with the help of [special] apparatus’. Müller laments that Willener’s ‘attempts to follow up on his theory were thwarted by the defects of recording techniques at that time’.

Happily, Müller himself had access to later, better equipment. ‘We have been trying at our clinic since 1980’, he writes, ‘to combine electromesenterography with Spindel’s alamograph, and in addition to use digital transformation for a quantitative analysis of the curves via computer.’

Müller reveals his greatest interpretive triumph: ‘The presence of a negative transference situation was not difficult to deduce from the following sequence: “Ro ... Pi ... le ... me ... 1o …”. The following translation is certainly an appropriate rendering: “Rotten pig. Leave me alone.”’

This lovely piece of deadpan, intentional nonsense, I am told, was swallowed whole by some readers, and perhaps also some journal editors.

A few years later, Guy Da Silva, a Montreal psychoanalyst, published several apparently quite serious papers about the psychoanalytical significance of borborygmi.

The most accessible (in my view, anyway) is his ‘Borborygmi as Markers of Psychic Work During the Analytic Session. A Contribution to Freud’s Experience of Satisfaction and to Bion’s Idea About the Digestive Model for the Thinking Apparatus’. This professionally dense monograph appeared in a 1990 issue of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis. Freud is Sigmund Freud, the psychoanalysis pioneer who lived in Vienna, Austria. Bion is Wilfred Ruprecht Bion, director of the London Clinic of Psychoanalysis in the 1950s, and later president of the British Psychoanalytical Society.

Guy Da Silva digested a little Freud together with a little Bion. He writes: ‘Borborygmi may signal the process and acquisition of new thoughts (symbolization) and the free associations derived from borborygmi often provide the key to the understanding of the session by linking the verbal flow of ideas to the underlying sensory and affective experience, thereby providing a “moment of truth”. Within the primitive maternal transference, borborygmi are often accompaniments to the fantasy or the hallucination of being fed by the analyst.’

The name Guy DaSilva will be familiar to some readers as the star of hundreds of psychologically gut-wrenching films, among them Beyond Reality 3, The Lube Guy, Attack of the Killer Dildos, and Porn-O-Matic 2000. But Guy DaSilva the actor and Guy Da Silva the psychoanalyst are not the same person, no matter how similarly stimulating their work may be.

Müller, Christian (1984). ‘New Observations on Body Organ Language.’ Psychotherapy and Psychosomics 42 (1–4): 124–26.

Da Silva, Guy (1990). ‘Borborygmi as Markers of Psychic Work During the Analytic Session. A Contribution to Freud’s Experience of Satisfaction and to Bion’s Idea About the Digestive Model for the Thinking Apparatus.’ International Journal of Psychoanalysis 71: 641–59.

–– (1998). ‘The Emergence of Thinking: Bion as the Link Between Freud and the Neurosciences.’ In M. Grignon (ed.) Psychoanalysis and the Zest for Living: Reflections and Psychoanalytic Writings in Memory of W. C. M. Scott. Binghamton, N.Y.: ESF Publishers.

The Tasting of the Shrew

If you like shrews, especially if you like them parboiled, you’ll want to devour a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Called ‘Human Digestive Effects on a Micromammalian Skeleton’, it explains how and why one of its authors – either Brian D. Crandall or Peter W. Stahl, we are not told which – ate and excreted a ninety-millimetre-long (excluding the tail, which added another twenty-four millimetres) northern short-tailed shrew (species name: Blarina brevicauda).

This was, in technical terms, ‘a preliminary study of human digestive effects on a small insectivore skeleton’, with ‘a brief discussion of the results and their archaeological implications’.

Crandall and Stahl are anthropologists at the State University of New York in Binghamton. The shrew was a local specimen, procured via snap trapping at an unspecified location not far from the school.

For the experiment’s input, preparation was exacting. After being skinned and eviscerated, the report says, ‘the carcass was lightly boiled for approximately 2 minutes and swallowed without mastication in hind and forelimb, head, and body and tail portions’.

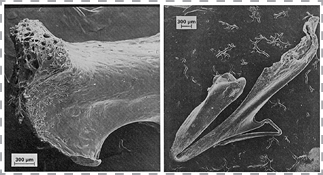

Here’s how Crandall and Stahl handled the output: ‘Faecal matter was collected for the following 3 days. Each faeces was stirred in a pan of warm water until completely disintegrated. This solution was then decanted through a quadruple-layered cheesecloth mesh. Sieved contents were rinsed with a dilute detergent solution and examined with a hand lens for bone remains.’ They then examined the most interesting bits with a scanning electron microscope, at magnifications ranging from 10 to 1000 times.

Digestive damage to a (left) surviving shrew humerus and (right) surviving shrew tibio-fibula

A shrew has lots of bony parts. All of them entered Crandall’s gullet, or maybe Stahl’s. But despite extraordinary efforts to find and account for each bone at journey’s end, many went missing. One of the major jawbones disappeared. So did four of the twelve molar teeth, several of the major leg and foot bones, nearly all of the toe bones, and all but one of the thirty-one vertebrae. And the skull, reputedly a very hard chunk of bone, emerged with what the report calls ‘significant damage’.

The vanishing startled the scientists. Remember, they emphasize in their paper that this meal was simply gulped down: ‘The shrew was ingested without chewing; any damage occurred as the remains were processed internally. Mastication undoubtedly damages bone, but the effects of this process are perhaps repeated in the acidic, churning environment of the stomach.’

Chewing, they almost scream at their colleagues, is only part of the story. In each little heap of remains from ancient meals, there be mystery aplenty.

Prior to this experiment, archaeologists had to, and did, make all kinds of assumptions about the animal bones they dug up – especially as to what those partial skeletons might indicate about the people who presumably consumed them. Crandall and Stahl, through their disciplined lack of mastication, have given their colleagues something toothsome to think about.

Crandall, Brian D., and Peter W. Stahl (1995). ‘Human Digestive Effects on a Micromammalian Skeleton.’ Journal of Archaeological Science 22 (6): 789–97.

May We Recommend

‘Pharyngeal Irritation After Eating Cooked Tarantula’

by Stephen J. Traub, Robert S. Hoffman, and Lewis S. Nelson (published in the Internet Journal of Medical Toxicology, 2001)

The Water Test

The study ‘Similar Preference for Natural Mineral Water between Female College Students and Rats’ pulls off a nice bit of interspecies diplomacy. Reading it end to end, you would be hard pressed to say who – the women or the rats – was most intended to benefit from the research.

Written by Esumi Yukiko of Shimane Women’s Junior College in Matsui, Japan, and Ohara Ikuo of Kobe Women’s University, and published in the Journal of Home Economics of Japan, this six-page monograph describes an apparently straightforward experiment.

The authors explain that their work was partly inspired by a simple fact: ‘The Society for the Study of Tasty Water, which is sponsored by the Ministry of Public Welfare, proposed hardness to be one of the most important requirements for tasty water.’ Therefore, they say, ‘The objectives of this study are to investigate the best mineral water for drinking by using hardness as an index, and whether the response of rats to mineral water can be extrapolated to that of humans.’

Yukiko and Ikuo conducted taste tests with sixteen healthy female humans, sixteen healthy female rats, and fourteen different brands (nine Japanese, two Belgian, and two French) of bottled water. The water, all of it, was uncarbonated. For good measure, the taste testers also taste-tested tap water.

The women drank from cups, the rats from objects called ‘drinking tubes’. The report specifies that the rats each weighed 160 grams, give or take three grams, and were ‘housed individually’. We are told nothing, not a blessed iota of fact, about the weight of the women, or about their living arrangements. The report also specifies that ‘Before beginning the experiment, each animal was fed on a commercial stock diet’, but says nothing about what the women consumed.

Yukiko and Ikuo reached two main conclusions. First, they write, ‘appropriate levels of minerals are needed for tasty drinking water, too little being as bad as too much, with around 58.3 milligrams/liter of hardness being most favorable’. Second, and perhaps more memorably: ‘The present study has demonstrated that the preference for different types of natural mineral water by female college students was similar to that by rats.’

Yukiko and Ikuo make no claim that theirs is the final word. For one thing, they point out, ‘The menstrual cycle of the subjects was not considered in this experiment, although taste sensitivity can be influenced by it.’

‘Similar Preference for Natural Mineral Water between Female College Students and Rats’ is not the only research study to proudly, explicity comparison-test college students and rats. But it may be the most exuberant since C. Lathan and P. E. Fields’s 1936 tell-all ‘A Report on the Test-retest Performances of 38 College Students and 27 White Rats on the Identical 25 Choice Elevated Maze’.

Yukiko, Esumi, and Ohara Ikuo (1999). ‘Similar Preference for Natural Mineral Water between Female College Students and Rats.’ Journal of Home Economics of Japan 50 (12): 1217–22.

Lathan, C., and P. E. Fields (1936). ‘A Report on the Test-retest Performances of 38 College Students and 27 White Rats on the Identical 25 Choice Elevated Maze.’ Journal of Genetic Psychology 49: 283–96.

Eggs Allsorts, Birdflesh Everykind

Which birds are the most edible, and which are the least? During and just after World War II, Hugh B. Cott of the University of Cambridge doggedly pursued these questions, using means that were waspy, feline, and human. His discoveries are summed up in a 154-page report entitled ‘The Edibility of Birds – Illustrated by 5 Years Experiments and Observations (1941–1946) on the Food Preferences of the Hornet, Cat and Man’.

In October 1941, Cott made a chance observation. While collecting and preserving bird skins in Beni Suef, Egypt, he discarded the meaty parts of a palm dove (Streptopelia senegalensis aegyptiaca) and a pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis rudis). Hornets descended upon the palm dove carcass, but ignored the kingfisher.

Cott, entranced, later offered other hornets a choice of different cuts (breast, wings, legs, and gut) of some forty different bird meats, in 141 experiments conducted in Beni Suef, Cairo, and Tripoli, Lebanon.

The hornets especially took to crested lark, greenfinch, white-vented bulbul, and house sparrow. They voted (metaphorically) thumbs down on golden oriole, hooded chat, masked shrike, and hoopoe, among others.

Cott conducted another forty-eight experiments, with nineteen kinds of bird meat, using three cats (two in Cairo, one in Tripoli) as tasters. In each experiment, the taster chose (or chose not to choose) between two different bird meats.

To answer the ‘which would a human eat’ question, Cott gathered data ‘from natives in the Lebanon; from personal experience and from observations sent in reply to a published inquiry; and from the [scientific] literature’. He drew most heavily from Reverend H. A. Macpherson’s occasionally mouthwatering 1897 tome A History of Fowling.

Surveying the results of all those taste tests of all those birds by hornets, cats, and people, Cott saw both rhyme and reason. He concluded that, in most cases, humans and cats ‘agreed with the hornets in rating more conspicuous species as relatively distasteful when compared with more cryptic species ... Birds which are relatively vulnerable and conspicuous ... appear in general to be more or less highly distasteful – to a degree likely to serve as a deterrent to most predators.’

At the other extreme, birds that have especially inconspicuous or camouflaged appearance, Cott almost cackles, ‘are also those which are especially prized for the excellence of their flesh’. The list of these includes the Eurasian woodcock, skylark, and the mallard duck.

Among the widely disliked were kingfishers, puffins, and bullfinches. Cott cautioned his readers that ‘palatability may change with growth and age of the bird; and it differs markedly in different parts of the same individual’.

But as with the special case of chickens and eggs, this is neither the beginning of the story nor its end. At roughly the same time, Cott was also running an extensive programme to test the palatability of every kind of bird egg he could find. The titles of his studies are pretty self-explanatory:

The Palatability of the Eggs of Birds – Illustrated by Experiments on the Food Preferences of the Hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus)

The Palatability of the Eggs of Birds: Illustrated by Three Seasons’ Experiments (1947, 1948 and 1950) on the Food Preferences of the Rat (Rattus norvegicus)

The Palatability of the Eggs of Birds – Illustrated by Experiments on the Food Preferences of the Ferret (Putorius furo) and Cat (Felis catus) – with Notes on Other Egg-Eating Carnivora’ (Those other carnivora are numerous, and include civets, mongooses and meerkats, hyenas, dogs and dingoes, otters, aardwolves, and foxes.)

Cott’s research programme could (although was not, so far as I know) be summarized as ‘Go suck eggs!’

Egg palatability experiments are potentially of great practical value. Island nations, Britain pre-eminently, were and are vulnerable to enemies who would block food shipments from overseas. One could counter the danger by discovering unknown or unappreciated edible native foodstuffs. A simple way to begin: collect bird eggs and test their palatability.

Egg collecting, like other research activities, is not without hazards. Cott relates an incident that’s documented in an 1882 monograph: ‘The victim, having collected a basket-full of the first eggs of the season, and wishing to procure more, had sent his wife to empty the basket in the village. In her absence, he fixed his rope to the cliff-top and made a second descent. Meanwhile a fox ran up, and gnawed the rope till it severed, at the place where the man had previously rubbed his yolk-smeared hands.’

Cott’s experiments mainly addressed a scientific question – demonstrating that, usually, the most conspicuous eggs taste terrible to whatever might want to eat them.

Cott also used human egg taste-testers. In 1946, he entered a six-year collaboration with the Cambridge Egg Panel, one of many similar bodies formed during World War II to help regulate the nation’s food supply. Under Cott’s direction, panellists tasted the eggs of 212 bird species. This resulted in a 129-page report called ‘The Palatability of Eggs and Birds: Mainly Based upon Observations of an Egg Panel’. It has raw data, supplemented with colourful highlights from the tasters’ own notes and from other sources, including Cott’s coterie of egg-collecting correspondents.

For the egg panellists, ‘samples were tested in the form of a scramble, prepared over a steam-bath, without any addition of fat or condiment’. Each taster assessed each sample on a scale dropping from ‘ideal’ way down to ‘repulsive and inedible’.

The paper concludes with a list of the different egg types ‘in descending order of acceptability’. Keep in mind that these are the aggregate preferences; individual tastes may vary. Most acceptable: chicken, then emu and coot, then black-backed gull. The eggs of last resort, as rated by official British egg-tasting persons: green woodpecker, Verreaux’s eagle owl, wren, speckled mousebird, and, dead last, black tit.

Cott’s work proved to be, among other things, inspirational. A generation later, Richard Wassersug (see page 173) cited it as both inspiration and, to some extent, guide for his research into the palatability of Costa Rican tadpoles.

Cott, Hugh B. (1945). ‘The Edibility of Birds.’ Nature 156 (3973): 736–37.

–– (1947). ‘The Edibility of Birds – Illustrated by 5 Years Experiments and Observations (1941–1946) on the Food Preferences of the Hornet, Cat and Man – and Considered with Special Reference to the Theories of Adaptive Coloration.’ Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 116 (3-4): 371–524.

–– (1948). ‘Edibility of the Eggs of Birds.’ Nature 161 (4079): 8–11.

–– (1951). ‘The Palatability of the Eggs of Birds - Illustrated by Experiments on the Food Preferences of the Hedgehog (erinaceus-europaeus).’ Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 121 (1): 1–40.

–– (1952). ‘The Palatability of the Eggs of Birds: Illustrated by Three Seasons’ Experiments (1947, 1948 and 1950) on the Food Preferences of the Rat (Rattus norvegicus); and with Special Reference to the Protective Adaptations of Eggs Considered in Relation to Vulnerability.’ Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 122 (1): 1–54.

–– (1953). ‘The Palatability of the Eggs of Birds – Illustrated by Experiments on the Food Preferences of the Ferret (Putorius-Furo) and Cat (Felis-Catus) – With Notes on Other Egg-Eating Carnivora.’ Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 123 (1): 123–41.

–– (1954). ‘The Palatability of Eggs and Birds: Mainly Based upon Observations of an Egg Panel.’ Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 124 (2): 335–463.

A Beef Boom

Before John Long applied his expertise to the problem, people tried many ways to make meat more tender – chewing it, pounding it, soaking it in enzymes.

The report, ‘Hydrodyne Exploding Meat Tenderness’, published in 1998 by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), describes Long’s act of creation as ‘a peacetime use for explosives’. It goes on: ‘Throughout John Long’s career as a mechanical engineer, he worked with explosives at Lawrence Livermore [National Laboratory]. His mission: preparing the Nation’s defense. He always wondered if the explosives he studied could be used for peaceful ends – like tenderizing meat. Then, after more than 10 years of retirement and long after the Cold War’s end, he began pursuing the Hydrodyne concept in earnest.’

The article explains that in 1992, Long teamed up with a meat scientist, Morse Solomon. Their first set-up was ‘an ordinary plastic drum filled with water and fitted with a steel plate at the bottom to reflect shock waves from an explosion’. By 1998, Long and Solomon were stuffing meat, water, and explosives into a seven-thousand-pound (3180-kilogram) steel tank covered with an eight-foot (2.4-metre) steel dome.

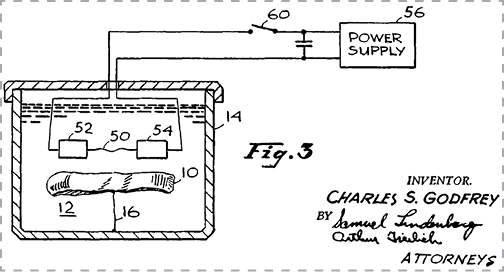

This official USDA story of how it all began looks past the fact that another man, Charles Godfrey of Berkeley, California, obtained a patent in 1970 for his ‘apparatus for tenderizing food’. Godfrey’s first sentence blasts away all confusion: ‘An article of food is tenderized by placing it in water and detonating an explosive charge in the vicinity thereof.’

Godfrey explains his method: ‘A cut of meat desired to be tenderized is placed under water within a tank. In view of the tendency of the meat to float, it may be necessary to tie the meat in position by a string ... A compressive pressure wave traveling at a speed higher than the velocity of sound may be generated in the water by a means, such as a charge of high explosive, which is supported above the meat by any suitable means, such as the leads which are used to ignite the detonator of the high explosive.’

Once the idea was out there, other scientists took to experimenting with beef, pork, chicken, and other things that went boom. A study in 2006 alluded to a scientist named Schilling who showed that ‘the hydrodynamic shock wave ... did not affect the color of cooked broiler breast meat’.

How to generate a shock pressure wave for tenderizing an article of food. Detail from US Patent no. 3,492,688

A pamphlet from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association bragged that ‘technology has been shown to improve the tenderness of beef by 30-80% and, the tougher the piece of meat, the greater the magnitude of improvement’. But so far the process works well only for small, sub-industrial quantities. The niggling problem, when applying explosives to heaps of flesh, is how to tenderize without pulverizing.

Lee, Jill (1998). ‘Hydrodyne Exploding Meat Tenderness.’ Agricultural Research (June): 8–10.

Godfrey, Charles S. (1970). ‘Apparatus for Tenderizing Food.’ US Patent no. 3,492,688, 3 February.

Pet Palates

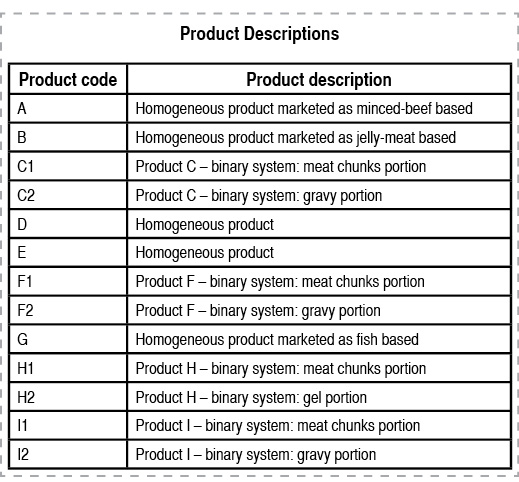

Pet food taste-testing by humans rose to a new level of formality with the publication of the scholarly study ‘Optimizing the Sensory Characteristics and Acceptance of Canned Cat Food: Use of a Human Taste Panel’. The author, G. J. Pickering of Brock University in St Catharines, Ontario, Canada, reports: ‘Cats are sensitive to flavour differences in diet, very discriminative in food selection, and clearly unable to verbalize their likes and dislikes. These issues have dogged the industry for decades.’

Pickering explains that taste tests with volunteer cats suffer three drawbacks. They are ‘expensive to maintain, time consuming, and yield limited and often equivocal data’. So he offers an alternative: ‘In-house tasting trials using a human taster are commonly conducted by the pet food industry, although there is a paucity of relevant information in the scientific literature.’

His study serves up a hearty helping of information. Human volunteers rated thirteen different commercial pet food samples, concentrating on eighteen so-called flavour attributes: sweet, sour/acid, tuna, herbal, spicy, soy, salty, cereal, caramel, chicken, methionine, vegetable, offaly, meaty, burnt, prawn, rancid, and bitter.

The tasting protocols depended on the texture of what was being tasted. When munching on meat chunks people assessed the hardness, chewiness, and grittiness (‘sample chewed using molars until masticated to the point of being ready to swallow’). But they gauged gravy/gel glops for viscosity and grittiness (‘sample placed in mouth and moved across tongue’).

The knowledge thus gained is only a first step. ‘It is now necessary’, Pickering writes, ‘to determine the usefulness and limits of sensory data gathered from human panels in describing and predicting food acceptance and preference behaviours in cats.’

Where the Pickering cat food paper was mainly for industrial consumption, a team of independent scholars – comprised of John Bohannon, Robin Goldstein, and Alexis Herschkowitsch – published ‘Can People Distinguish Pâté From Dog Food?’ to address a societal concern: ‘the potential of canned dog food for human consumption by assessing its palatability alone’. The study concludes somewhat perplexedly that (1) ‘human beings do not enjoy eating dog food’ and (2) are ‘not able to distinguish its flavor profile from other meat-based products that are intended for human consumption’.

Perhaps alcohol helped this to happen. The dog monograph is published by the American Association of Wine Economists (AAWE), while the cat paper is written by a professor of biological sciences/wine science, and appears in the Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, which serves up complementary studies such as ‘The Influence of Polyphenol Rich Apple Pomace or Red-Wine Pomace Diet on the Gut Morphology in Weaning Piglets’.

Pickering, G. J. (2009). ‘Optimizing the Sensory Characteristics and Acceptance of Canned Cat Food: Use of a Human Taste Panel.’ Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 93 (1): 52–60.

Bohannon, John, Robin Goldstein, and Alexis Herschkowitsch (2007). ‘Can People Distinguish Pâté From Dog Food?’ AAWE Working Paper no. 36, April.

Measured Attitudes to Chocolate

A report called ‘The Development of the Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire’, published in 1998, tells how three researchers at the University of Wales, Swansea, cooked up a new analytic tool.

Psychologists had long craved a way to assess someone’s craving for chocolate. Why chocolate? Because ‘chocolate is by far the most commonly craved food’. It tempts chocoholics, and also academics who hunger for knowledge and perhaps recognition.

The desired goal – the perhaps impossible dream – is to measure and compare any two people’s chocolate cravings as reliably as one can measure and compare the heights of two tables. But cravings are often intertwined with emotions, and table heights are not. This explains why table heights are easier to measure.

All prior attempts to measure cravings, say study co-authors, David Benton, Karen Greenfield, and Michael Morgan, were ‘unreliable’. They devised a tool that, they say, ‘provides a quantitative estimate of the fundamental attitudes to chocolate’. It measures the magnitude of the craving; it also measures the guilt feelings.

The tool – called the Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire – is a simple list of twenty-four statements. Some are strictly about craving:

The thought of chocolate often distracts me from what I am doing.

My desire for chocolate often seems overpowering.

Some are about guilt:

I feel guilty after eating

often wish I hadn’t.

To measure an individual’s chocolate craving, have the person read each statement and then indicate, by marking on a little ruled line, whether the statement is ‘not at all like me’ or ‘very much like me’ or somewhere in between. A bit of statistical manipulation, and hey, presto! out pops a set of numbers that describe the craving.

Benton, Greenfield, and Morgan tested and calibrated their new tool on some student volunteers. In addition to answering the questionnaire, the volunteers played a sort of mechanical game. By pressing a lever, they could obtain a reward – a little button made of chocolate. As the game progressed, they had to press the bar more and more times (twice, then four times, then eight, then sixteen, etc.) before another chocolate would pop out. The point at which someone refused to keep playing this game indicated the strength of their craving (or, one might argue after some time has passed, the fullness of their stomach).

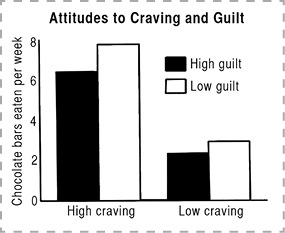

Figure: ‘The relationship between craving, guilt, and the eating of chocolate bars … High craving but not guilt was associated with the eating of a higher number of chocolate bars’

Afterwards, the researchers compared people’s scores on the Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire with their craving strength as measured in the press-the-lever-and-get-a-treat game.

The questionnaire results accorded well with what happened in the game. In most cases, if the questionnaire said someone had a high craving for chocolate, that person was persistent at making the frustrating machine deliver up chocolates. Thus, the little questionnaire is a cheap, fairly accurate way to measure chocolate craving and also to measure guilt.

In their report, the researchers announce that, using their new tool, they made an exciting new psychological discovery: that ‘craving but not guilt was associated with the eating of chocolate bars’.

Benton, David, Karen Greenfield, and Michael Morgan (1998). ‘The Development of the Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire.’ Personality and Individual Differences 24 (4): 513–20.

Cramer, Kenneth M., and Mindy Hartleib (2001). ‘The Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire: A Psychometric Evaluation.’ Personality and Individual Differences 31 (6): 931–42.

PAH to Whisky

Whisky and candlelight, consumed repeatedly over many years, involve some measure of danger. Two Dutch research projects tried to take that measure. They hoped to confront the spectre of death – to either confirm or disprove the worry that good whisky and sacred candles, singly or in combination, are very, very bad for a body.

The very specific object to be measured, both in the booze and in the candle smoke, was a particular group of chemicals. Known by the acronym ‘PAHs’ (say it aloud, with pursed lips, to see how disgustingly nasty some people think they are) – these tasty, smelly molecules have a fairly well-deserved reputation for causing cancer and other illnesses.

Jos Kleinjans, an environmental health professor at the University of Maastricht, led a pair of inquisitions. He joined with one bunch of colleagues to give whisky a good going-over. With a different bunch, he sniffed into church candle (and also church incense) fumes, in search of insidious nastiness.

The whisky came first. As detailed in a report published in 1996 in the Lancet, Kleinjans and five friends obtained some of the finest whiskies on Earth. For comparative purposes, they also picked up some of the cheap stuff.

From Scotland they got six malts – Laphroaig, Oban, Glenkinchie, Glenfiddich, Highland Park, and Glenmorangie – and also four blends – Famous Grouse, Chivas Regal, Johnnie Walker Red, and Ballantines.

From North America, five bourbons – Southern Comfort, Virginia Gentleman, Jack Daniel’s, Four Roses, and Old Overholt.

From Ireland, three whiskies – Bushmill’s Malt, Jameson, and Tullamore Dew.

‘Carcinogenic PAHs’, the scientists announced, ‘were present in all whisky brands’ but ‘it is apparent that Scotch malts have the highest carcinogenic potential’. Eye-pokingly, they revealed that the most expensive Scotch malts contain the highest levels of danger.

No worries, though, or at least not many. The report concludes: ‘Compared with smoked and char-broiled food products ... PAH concentrations in whiskies are low, and are not likely to explain the cancer risks of whisky consumption.’ This is danger with a most tiny ‘d’. It is the spice of life, and also of whisky.

An almost biblical seven long years later, Kleinjans and three other friends published a report called ‘Radicals in the Church’. It tells of their adventures in a Roman Catholic Church – the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Basiliek in Maastricht. There, they sampled the fumes from a standard (to the extent that such things are standard) nine-hour session of burning candles and incense. They also, literally for good measure, sampled the air before and after what they call a ‘simulated service’ in a large basilica. The PAH levels, they discovered, are higher than in a dose of whisky, but perhaps not high enough to shed clear light on the question ‘is it dangerous?’

And so their report ends with a murky diagnosis: ‘It cannot be excluded that regular exposure to candle- or incense-derived particulate matter results in increased risk of lung cancer or other pulmonary diseases.’

Kleinjans, Jos C, S., Edwin J. C. Moonen, Jan W. Dallinga, Harma J. Albering, Anton E. J. M. van den Bogaard, and Frederik-Jan van Schooten (1996). ‘Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Whiskies.’ Lancet 348: 1731.

De Kok, T. M. C. M., J. G. F. Hogervorst, J. C. S. Kleinjans, and J. J. Briede (2004). ‘Radicals in the Church.’ European Respiratory Journal 24: 1–2.

Standard Food Glops

When food manufacturers put nutrition info on their labels, they can either (a) invent the numbers (and risk going to prison) or (b) chemically analyse the food to see how much of it is saturated fat, or sodium, or vitamin A, or some other particular nutrient, mineral, or vitamin. The analytical chemists, if they are honest and honourable, must know whether they can trust their own measurements – and so they test their equipment by first analysing some officially measured and certified ‘typical’ foodstuff.

For just $839 (£534) one can buy the essence of an officially measured and certified ‘typical diet’ – officially prepared and bottled by the US government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The money gets you twelve grams of blended, ‘freeze-dried homogenate of mixed diet foods’, delivered in a pair of six-ounce bottles.

An accompanying NIST document, called ‘Certificate of Analysis, Standard Reference Material 1548a, Typical Diet’, makes no claims as to tastiness. The certificate notes that these possibly delicious dollops are ‘not for human consumption’.

Each portion contains a soupçon of mystery, a hint of inexactitude in its numbers. The Certificate of Analysis makes mention of ‘uncertainties that may reflect only measurement precision, may not include all sources of uncertainty, or may reflect a lack of sufficient statistical agreement among multiple methods’. (The certificate goes on to mention, with a metaphorical twirling of its moustache and twinkling of its eyes, that ‘there is insufficient information to make an assessment of the uncertainties’.)

Despite the imprecision, it would be wrong, very wrong, to say that the diet is slopped together carelessly. To the contrary, it was ‘prepared from menus used for the metabolic studies at the Human Study Facility’ of the US Food and Drug Administration. ‘Food items in prescribed quantities representing a four-day menu cycle were pooled/combined into a master menu ... The material was freeze-dried, pulverized, sieved, and radiation sterilized at a dose of 2.5 mrad to prevent bacterial growth’, then ‘blended, bottled, and sealed under nitrogen’.

In addition to the typical diet, NIST produces items conceivably of appeal to more specialized palates: baby food composite, peanut butter, baking chocolate, meat homogenate, and Lake Superior fish tissue. The latter includes standard amounts of fat, fatty acid, pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), mercury, and methylmercury.

NIST offers many kinds of useful and, to the connoisseur, delightful Standard Reference Materials. Their catalogue runs to 145 pages.

Prospective purchasers can peruse page after page of bodily fluids and glops, among them bilirubin, cholesterol, and ascorbic acid in frozen human serum. There are other specialty products in dizzying variety: toxic metals in bovine blood, naval brass, domestic sludge, and plutonium-242 solution, to name four.

Prices are mostly in the $300 to $600 range. At the high end, you will find New York/New Jersey waterway sediment for $610. There are bargains to be had, including an item called ‘cigarette ignition strength, standard’, on offer at one carton (two hundred cigarettes) for $192. Alas, ‘multi drugs of abuse in urine’ was out of stock, the last time I looked.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (2009). ‘Certificate of Analysis – Standard Reference Material 1548A: Typical Diet,’ https://www-s.nist.gov/srmors/view_detail.cfm?srm=1548A.

Sharpless, Katherine E., Jennifer C. Colbert, Robert R. Greenberg, Michele M. Schantz, and Michael J. Welch (2001). ‘Recent Developments in Food-Matrix Reference Materials at NIST.’ Fresenius Journal of Analytic Chemistry 370: 275–78.

In Brief

‘Distinction Between Heating Rate and Total Heat Absorption in the Microwave-Exposed Mouse’

by Christopher J. Gordon and Elizabeth C. White (published in Physiological Zoology, 1982)

According to the authors at the US Environmental Protection Agency, ‘This investigation assesses the ability of the heat-dissipating system of the mouse to respond to equivalent heat loads (e.g., J/g) administered at varying intensities (e.g., J/g/s or W/kg). Use of a microwave exposure system provided a means to administer exact amounts of energy at varying rates in awake, free-moving mice.’

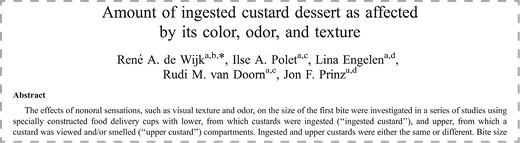

Implications of Custard

There is one individual who, above all others, has plumbed the effects of custard.

René A. de Wijk is based at the Wageningen Centre for Food Sciences in the Netherlands. During a four-year burst of scholarship, demonstrating his stunning productivity, de Wijk published more than ten custard-centric research reports, each of them a substantial contribution to our understanding of, and relationship with, custard.

Do not think of custard researchers as being solitary, asocial creatures. Certainly de Wijk is not. He shares co-authorship credit with a happy variety of colleagues.

In 2001, de Wijk teamed up with H. Weenen, L. J. Van Gemert, R. J. M. Van Doorn, and G. B. Dijksterhuis. The result was ‘Texture and Mouthfeel of Semi-Solid Foods: Commercial Mayonnaises, Dressings, Custard Desserts and Warm Sauces’, which delighted readers of the Journal of Texture Studies.

Two years later, de Wijk, together with Weenen and two others, published a pudding-studies instant classic, ‘The Influence of Bite Size and Multiple Bites on Oral Texture Sensations’. This carefully worded document describes a pair of experiments.

First, the scientists observed what happens when a person takes carefully measured bites of a vanilla custard dessert. Eating custard in single bites, they observed, ‘affected perception of thickness, temperature, astringency, and creaminess’. In the other experiment, the custard-chewing volunteers began taking bites from one vanilla custard dessert – but then suddenly switched to biting an entirely different vanilla custard dessert. The effect was fairly subtle: ‘sensations of thickness and fatty afterfeel’ became more noticeable.

In 2003, de Wijk and colleagues issued two reports about the interaction of saliva and custard. In one, they tested the effect of adding saliva to custard prior to eating that custard. The report carefully notes that ‘saliva had previously been collected from the subjects and each subject received his/her own saliva’. The other report looked at ‘whether and how the amount of saliva a subject produces influences the sensory ratings’ when that person then gobbles a vanilla custard dessert. The results are summarized memorably: ‘A subject with a larger saliva flow rate during eating did not rate the foods differently from a subject with less saliva flow.’

Another de Wijk report from that year explored the effects of manipulating custard inside one’s mouth. The activities ‘ranged from simply placing the stimulus on the tip of the tongue to vigorously moving it around in the mouth’. To gain some perspective, the test subjects also had to manipulate mayonnaise, although that was done separately.

De Wijk, together with four colleagues, then came out with his magnum opus, a distillation of what is known about the sensation of mouthing custard and an intellectually, gustatorially stimulating read. For some readers, ‘Amount of Ingested Custard Dessert as Affected by Its Color, Odor, and Texture’ will recall the work of Marcel Proust, for it deals entirely with what happens when a sensitive human being takes the very first bite of custard.

Weenen, H., L. J. Van Gemert, R. J. M. Van Doorn, G. B. Dijksterhuis, and R. A. de Wijk (2001). ‘Texture and Mouthfeel of Semi-Solid Foods: Commercial Mayonnaises, Dressings, Custard Desserts and Warm Sauces.’ Journal of Texture Studies 34 (2), 159–79.

De Wijk, R. A., L. Engelen, J. F. Prinz, and H. Weenen (2003). ‘The Influence of Bite Size and Multiple Bites on Oral Texture Sensations.’ Journal of Sensory Studies 18 (5): 423–35.

Engelen, L., R. A. de Wijk, J. F. Prinz, A. M. Janssen, H. Weenen, and F. Bosman (2003). ‘A Comparison of the Effects of Added Saliva, Alpha-Amylase and Water on Texture Perception in Semi-Solids.’ Physiology and Behavior 78: 805–11.

Engelen, L., R. A. de Wijk, J. F. Prinz, A. Van der Bilt, and F. Bosman (2003). ‘The Relation between Saliva Flow after Different Stimulations and the Perception of Flavor and Texture Attributes in Custard Desserts.’ Physiology and Behavior 78 (1): 165–69.

De Wijk, R. A., L. Engelen, and J. F. Prinz (2003). ‘The Role of Intra-Oral Manipulation on the Perception of Sensory Attributes.’ Appetite 40 (1): 1–7.

De Wijk, R. A., et al. (2004). ‘Amount of Ingested Custard Dessert as Affected by its Color, Odor, and Texture.’ Physiology and Behavior 82 (2–3): 397–403.

Janssen, A. M., Marjolein E. J. Terpstra, R. A. de Wijk, and J. F. Prinz (2007). ‘Relations Between Rheological Properties, Saliva-induced Structure Breakdown and Sensory Texture Attributes of Custards.’ Journal of Texture Studies 38 (1): 42–69.

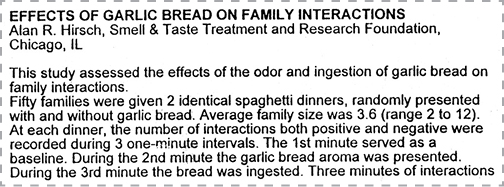

The Garlicky Family

‘This study assessed the effects of the odor and ingestion of garlic bread on family interactions.’ With those words, Alan R. Hirsch of the Smell & Taste Treatment and Research Foundation, in Chicago, declared the purpose and the breadth of his research. However, Hirsch did not analyse the matter as deeply as he could have.

This is not to say that Dr Hirsch was lazy. His experiment examined the interactions of garlic bread and fifty families, an undertaking that involved the preparation and consumption of not just fifty, but a full one hundred meals. Each family was made to experience dinner with garlic bread, and also dinner without. For each family, the order of those two experiences was determined randomly.

Hirsch published details in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine. The families ranged in size from two to twelve people. In their breaded meal, each family had to endure a full minute before being exposed to the garlicky aroma. Hirsch’s published account reads like the science adventure tale it is. ‘During the second minute’, he writes, ‘the garlic bread aroma was presented. During the [third] minute the bread was ingested.’

The rest of the story can and is told in numbers. ‘Smelling and eating garlic bread decreased the number of negative interactions between family members’, the report says, and ‘the number of pleasant interactions increased.’ Hirsch reached the conclusion that: ‘Serving garlic bread at dinner enhanced the quality of family interactions. This has potential applications in promoting and maintaining shared family experiences, thus stabilizing the family unit, and also may have utility as an adjunct to family therapy.’

But what, biochemically, is the mechanism for this effect? On that level, Hirsch is mum.

For an answer, one must look elsewhere, perhaps to the Journal of Biological Chemistry, which published a study called ‘The Active Principle of Garlic at Atomic Resolution’. The German authors of that report caution that ‘despite the fact that many cultures around the world value and utilize garlic as a fundamental component of their cuisine as well as of their medicine cabinets, relatively little is known about the plant’s protein configuration that is responsible for the specific properties of garlic.’

This scarcity of knowledge also obtruded itself in 1998, when three scientists in Wales published ‘What Sort of Men Take Garlic Preparations?’ Their conclusion: ‘Men who take garlic supplements are generally similar to non-garlic users.’

Hirsch, Alan R. (2000). ‘Effects of Garlic Bread on Family Interactions.’ Psychosomatic Medicine 62 (1): 103.

Kuettner, E. Bartholomeus, Rolf Hilgenfeld, and Manfred S. Weiss (2002). ‘The Active Principle of Garlic at Atomic Resolution.’ Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (48): 46402–7.

Thomas, H. F., P. M. Sweetnam, and B. Janchawee (1998). ‘What Sort of Men Take Garlic Preparations?’ Complementary Therapies in Medicine 6: 195–97.

Teabagging in the Name of Science

Political teabagging and sexual teabagging have attracted lots of controversial attention in recent years, but a lesser-known variety – research teabagging – has much to recommend it.

In case you have not encountered the word ‘teabagging’, here’s some linguistic background. Political teabagging takes its name from a twisted, angry dip into American/British history: the ‘Boston Tea Party’ anti-tax protest of 1773, while sexual teabagging involves dipping one particular body part into another, a bit like a teabag is dipped in a mug.

Research teabagging, in contrast, confronts rather different matters – using teabags to explore scientific and medical questions.

In 2009, a group of nine Japanese researchers told how they used bags of green tea to fight a disgusting odour that arises from the hands of extremely unlucky stroke victims. Their report, published in the journal Geriatrica and Gerontology International, ‘Four-Finger Grip Bag with Tea to Prevent Smell of Contractured Hands and Axilla in Bedridden Patients’, found that clutching a bag filled with green tea ‘could substantially control smell in these bedridden patients’.

In 1997, a nurse clinician in Winnipeg, Canada, published a report in the Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing called ‘Does Application of Tea Bags to Sore Nipples While Breastfeeding Provide Effective Relief?’ This is a happy story, concluding that ‘warm water or tea bag compresses are an inexpensive, equally effective treatment’ that ‘can prevent further complications such as severe pain, cracking, bleeding, inadequate milk ejection, and, ultimately, premature weaning.’

Seven years later, an American medical team reported a case of drug abuse via teabags. Their paper, called ‘The Fentanyl Tea Bag’, appeared in the journal Veterinary and Human Toxicology. It describes ‘a 21-year-old woman who steeped a fentanyl patch in a cup of hot water and then drank the mixture. Coma and hypoventilation resulted’.

Another group of teabaggers used maggots. A 2009 issue of Turkiye Parazitoloji Dergisi (the Turkish Parasitology Digest) featured a monograph entitled ‘The Treatment of Suppurative Chronic Wounds with Maggot Debridement Therapy’. It tells how ‘sterile maggots, produced in university laboratories and by private industry, are usually applied to the wound either by using a cage-like dressing or a tea bag-like cage’.

More than thirty years before that, a team of biomedical teabaggers took aim at brown dog ticks. Their 1974 study in the Bulletin of Epizootic Diseases of Africa assessed the ‘teabag method’, using a teabag-like structure filled with maggots for ‘testing acaricide susceptibility of the brown dog tick rhipicephalus sanguineus’.

Unlike the other forms of teabagging, which involve an element of exhibitionism, research teabagging is a quiet endeavour, typically conducted in low-key fashion, in laboratories or hospitals.

Of the bunch, it’s the only one that’s typically accompanied and lubricated by many, many cups of actual, teabag-brewed tea.

Kigaye, M. K., and J. G. Matthysse (1974). ‘Testing Acaricide Susceptibility of the Brown Dog Tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Latreille, 1806). II Teabag Method.’ Bulletin of Epizootic Diseases of Africa 22 (3): 279–85.

Mumcuoglu, Kosta Y., and Aysegul Taylan Ozkan (2009). ‘The Treatment of Suppurative Chronic Wounds with Maggot Debridement Therapy.’ Turkiye Parazitoloji Dergisi 33 (4): 307–15.

Fukuoka, Yumiko, Hisashi Kudo, Aiko Hatakeyama, Naomi Takahashi, Kayoko Satoh, Naoko Ohsawa, Mayumi Mutoh, Masahiko Fujii, and Hidetada Sasaki (2009). ‘Four-Finger Grip Bag with Tea to Prevent Smell of Contractured Hands and Axilla in Bedridden Patients.’ Geriatrica and Gerontology International 9 (1): 97–99.

Fermin Barrueto, Mary Ann Howland, Robert S. Hoffman, and Lewis S. Nelson (2004). ‘The Fentanyl Tea Bag.’ Veterinary and Human Toxicology 46 (1): 30–31.

Lavergne, Noelie A. (1997). ‘Does Application of Tea Bags to Sore Nipples While Breastfeeding Provide Effective Relief?’ Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 26 (1): 53–58.

Brennan, Mike, Janet Hoek, and Philip Gendall (1998). ‘The Tea Bag Experiment: More Evidence on Incentives in Mail Surveys.’ International Journal of Market Research 40 (4): 347–52.

In Brief

‘Impaction of an Ingested Table Fork in a Patient with a Surgically Restricted Stomach’

by A. Cassaro and M. Daliana (published in the New York State Journal of Medicine, 1992)

Wascally Wabbit Wrapping

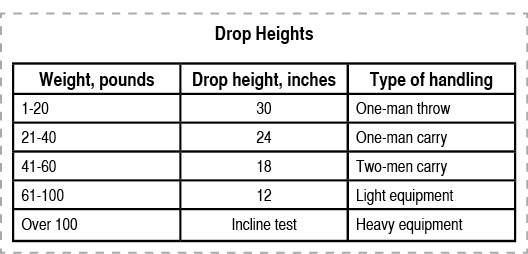

There are few peer-reviewed papers on the subject of designing and testing an improved packaging for large hollow chocolate bunnies. Of these articles, the most bouncily thorough is one called ‘Designing and Testing an Improved Packaging for Large Hollow Chocolate Bunnies’. Though just seven pages long, it contains everything a research report ought to have.

The opening section describes the nature of the problem: ‘To test the properties required for the packaging of hollow chocolate Easter bunnies to resist any hazards in the distribution environment.’ The concluding section suggests that more research is needed.

The experiments are described in clear, spare prose, as are the materials (‘The product for our tests was a hollow milk chocolate figure with the shape of an Easter Bunny’), the testing equipment (‘The drop testing machine had two drop leaves controlled with a foot paddle’), and the procedures (‘Each series of nine bunnies per design was divided into three sets each of three packed bunnies’). At the end comes a list of references, one of which is C. M. Harris’s gently moving benchmark ‘Shock and Vibration Handbook’.

The paper is visually informative, with four charts and seven technical renderings. The eye is drawn to Figure 7, a perspective drawing of a chocolate bunny. The bunny is wearing an apron and holding a carrot, and has no legs. The ears point straight up. The facial expression is enigmatically bland, suggesting both Mona Lisa and a mid-career clerk, while resembling neither.

The bunny-packaging scientists, G. M. Greenway and R. E. Garcia Via of the University of Missouri-Rolla’s package sealing laboratory, list their results and discuss their conclusions. Commendably, they identify the study’s limitations, especially the main one, that ‘availability of materials – especially bunnies – was a constraint during this experiment’.

Although there are few peer-reviewed papers on the subject of designing and testing an improved packaging for large hollow chocolate bunnies, there is a considerable body of published research concerning other problems in the discipline of packaging. Want a good introduction to the chemical physics of plastic bags? P. M. Vilela and a colleague at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, in Lima, published a corker in the European Journal of Physics in 1999. It involves deformation, spaghetti, Boltzmann’s superposition principle, non-linear least-squares fits to the viscous creep, gentle wriggles, and a warmly satisfying title: ‘Viscoelasticity: Why Plastic Bags Give Way When You Are Halfway Home’.

Greenway, G. W., and R. E. Garcia Via (1977). ‘Designing and Testing an Improved Packaging for Large Hollow Chocolate Bunnies.’ TAPPI Journal 80 (8): 133.

Vilela, P. M., and D .Thompson (1999). ‘Viscoelasticity: Why Plastic Bags Give Way When You Are Halfway Home.’ European Journal of Physics 20 (1): 15–20.

Crisp Sounds

Crispness is associated with crunchiness, but your ears make a difference. That’s the takeaway-and-chew-on-it message of an Oxford University study entitled ‘The Role of Auditory Cues in Modulating the Perceived Crispness and Staleness of Potato Chips’.

The authors, experimental psychologists Massimiliano Zampini and Charles Spence, wax distantly poetical: ‘We investigated whether the perception of the crispness and staleness of potato chips can be affected by modifying the sounds produced during the biting action. Participants in our study bit into potato chips with their front teeth while rating either their crispness or freshness using a computer-based visual analog scale.’

They recruited volunteers who were willing to chew, in a highly regulated way, on Pringles potato crisps. Pringles themselves are, as enthusiasts well know, highly regulated. Each crisp is of nearly identical shape, size, and texture, having been carefully manufactured from reconstituted potato goo.

The volunteers were unaware of the true nature of their encounter – that they would be hearing adulterated crunch sounds. But whatever risks this entailed were small. The experiment, Zampini and Spence take pains to say in their report, ‘was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were paid £5 for taking part in the study.’

Each volunteer sat in a soundproofed experimental booth, wearing headphones, facing a microphone, and operating a pair of foot pedals.

The headphones delivered Pringles crunch sounds that, though born in the chewer’s mouth, had been captured by the microphone and electronically cooked. At times, the crunch sounds were delivered to the headphones with exacting, lifelike fidelity. At other times, the sounds were magnified. At still other times, only the high frequencies of the crunch were intensified.

The foot pedals were the means by which a volunteer could register his or her judgements as to (a) the crispness and (b) the freshness of a particular crisp.

Each crisp’s crispness was judged from a single, headphone-enhanced bite delivered with the front teeth. Zampini and Spence adopted this approach for two reasons. It maximized the uniformity of the participant’s contact with each crisp. And previous research, by others, showed that the sound of the first bite is what counts most for judging crispness.

The results? As the report puts it: ‘The potato chips were perceived as being both crisper and fresher when either the overall sound level was increased, or when just the high frequency sounds (in the range of 2 kilohertz–20 kilohertz) were selectively amplified.’

Zampini and Spence say this gives new insight on an old research finding. In 1958, in the Journal of Applied Psychology, G. L. Brown ‘reported that bread was judged as being fresher when wrapped in cellophane than when wrapped in wax paper’. The sound made by wrappers, they hazard, may have unappreciated influence.

There exists a Dutch study showing that generally you can judge a book by its cover. I mention it here only for contrast, because the Oxford report implies that maybe you can’t judge the crunch of a crisp by the crackle of its wrapper.

In 2008, Zampini and Spence were awarded the Ig Nobel Prize in the field of nutrition for their efforts to electronically modify crisp sounds to seem crisper and fresher.

Zampini, Massimiliano, and Charles Spence (2004). ‘The Role of Auditory Cues in Modulating the Perceived Crispness and Staleness of Potato Chips.’ Journal of Sensory Studies 19 (5): 347–63.

Brown, G. L. (1958). ‘Wrapper Influence on the Perception of Freshness in Bread.’ Journal of Applied Psychology 42: 257–60.

Piters, Ronald A. M. P., and Mia J. W. Stokmans (2000). ‘Genre Categorization and Its Effect on Preference for Fiction Books.’ Empirical Studies of the Arts 18 (2): 159–66.

Enough Already

‘Had enough?’ This simple query drives Brian Wansink of Cornell University, in New York, to conduct experiment after experiment after experiment. Had enough popcorn? Had enough candy? Had enough rum and Coke? Wansink wants to know.

Most of the other experts on ‘Had enough?’ are nutritionists, mothers, or waiters. They serve up their conclusions in a sandwich of nutritionist, maternal, or waiterly intuition. Professor Wansink is an economist. He presents his thoughts atop beds of freshly harvested data.

Wansink methodically chews at the riddle of what makes a trencherman. He proceeds substance by substance.

As if calibrating his equipment, Wansink began with plain, pure water in bottles, publishing a paper in 1996 called ‘Can Package Size Accelerate Usage Volume?’ The answer, he says, is yes.

Five years later, Wansink and a colleague, the evocatively named graduate student Se-Bum Park, published a report in the journal Food Quality and Preference. It describes the experiment they conducted with patrons at a screening of the film Payback, which stars Mel Gibson. These discriminating cineastes munched free popcorn. The researchers noted that ‘moviegoers who had rated the popcorn as tasting relatively unfavorable ate 61% more popcorn if randomly given a large container than a smaller one’.

The next year, 2002, saw publication of ‘How Visibility and Convenience Influence Candy Consumption’ in the journal Appetite. These candy results were as startling as the earlier popcorn findings. People ate more chocolate drops if the candy jar was kept on a desk rather than somewhere less handy or visible.

A study published in 2004 described a series of relatively complex experiments involving jelly beans and M&Ms. This was an attempt to probe how ‘the structure of an assortment (e.g., organization and symmetry or entropy) moderates the effect of actual variety on perceived variety’.

The jelly beans caused problems. The report says merely that ‘ 23 [people] indicated that they did not like jelly beans and were dropped from the study. Five others were deleted from the analysis because they accidentally spilled the jelly beans or emptied the entire tray onto the table and scooped the jelly beans into their pockets.’

Wansink holds the university’s John S. Dyson chair of marketing and applied economics. The chair was endowed by Robert R. Dyson to honour his brother. John S. Dyson created the ‘I ♥ NY’ tourism campaign, which, for more than three decades now, has not stopped serving up television ads, and magazine ads, and other ads, ad nauseum, to drive the phrase ‘I ♥ NY’ through the eyes and ears and into the brains of billions of human beings round the globe.

Wansink ascended the John S. Dyson chair in 2005, after spending eight years at the University of Illinois, where he held several titles, including that of Julian Simon memorial faculty fellow in marketing. That fellowship was endowed to honour the memory of Julian Simon, an economist who himself had an obsession with ‘Had enough?’ Simon’s former colleagues say he was ‘a man who won an international reputation for his buoyant and often controversial views on the limitless potential of human beings to meet and overcome the challenge of declining resources – views that won him the one-word description of “doomslayer”.’

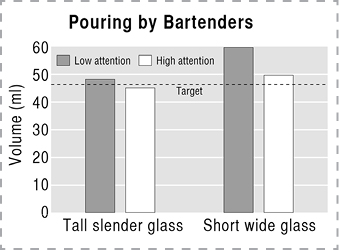

In Wansink’s later experiments, people slurped rum and Cokes from glasses that were tall and slim or short and stout; munched roasted nuts and a pretzel variety mix from party bowls of various sizes; and spooned soup from bottomless bowls – a challenge of rising resources. The bowls were not literally bottomless – rather, they ‘slowly and imperceptibly refilled as their contents were consumed’. A bottomless soup bowl experiment, in which people showed themselves to be nearly insatiable, earned Professor Wansink an Ig Nobel Prize, awarded in 2007, in the field of nutrition.

Wansink has revisited the popcorn question, and more recently, in the BMJ, the booze.

The long and short of bartenders’ pours

Fans can hope that one day he will revisit the soup. In a press release some years ago, Wansink said, ‘We thought it would be interesting to examine personality types based on strongly expressed soup preferences.’ However, he has yet to publish on this topic in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Wansink, Brian (1996). ‘Can Package Size Accelerate Usage Volume.’ Journal of Marketing 60: 1–14.

–– (2002). ‘Changing Eating Habits on the Home Front: Lost Lessons from World War II Research.’ Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 21 (1): 90–99.

Kahn, Barbara E., and Brian Wansink, (2004). ‘The Influence of Assortment Structure on Perceived Variety and Consumption Quantities.’ Journal of Consumer Research 30: 519–33.

Wansink, Brian, and Koert van Ittersum (2003). ‘Bottoms Up! The Influence of Elongation on Pouring and Consumption Volume.’ Journal of Consumer Research 30: 455–63.

–– (2005). ‘Shape of Glass and Amount of Alcohol Poured: Comparative Study of Effect of Practice and Concentration.’ BMJ 331: 1512–14.

Wansink, Brian, and Junyong Kim (2005). ‘Bad Popcorn in Big Buckets: Portion Size Can Influence Intake as Much as Taste.’ Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 37 (5): 242–45.

Wansink, Brian, and Se-Bum Park (2000). ‘Accounting for Taste: Prototypes that Predict Preference.’ Journal of Database Marketing 7: 308–20.

–– (2001). ‘At the Movies: How External Cues and Perceived Taste Impact Consumption Volume.’ Food Quality and Preference 12 (1): 69–74.

Wansink, Brian, James E. Painter, and Jill North (2005). ‘Bottomless Bowls: Why Visual Cues of Portion Size May Influence Intake.’ Obesity Research 13 (1): 93–100.

Painter, James E., Brian Wansink, and Julie B. Hieggelke (2002). ‘How Visibility and Convenience Influence Candy Consumption.’ Appetite 38 (3): 237–38.

Wansink, Brian, and Matthew M. Cheney (2005). ‘Serving Bowls, Serving Size, and Food Consumption: A Randomized Controlled Trial.’ JAMA – Journal of the American Medical Association 293 (14): 1727–28.