Six

Money Can Be Valuable

In Brief

‘How High Can a Dead Cat Bounce?: Metaphor and the Hong Kong Stock Market’

by Geoff P. Smith (published in Linguistics and Language Teaching, 1995)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Money destruction in your skull • The lure of piracy, for economists • 2127 rounds of rock, paper, scissors per day • A careful look inside Russian underwear • Foucault and footie • The shapely heads of CEOs • Griffiths, slot-machine psychologist • Perfume for the poor • Author, author, author, author, author, author, author, author, author, author • $100,000,000,000,000 • Corporate tiers of a clown

All Torn Up

If you have never watched someone rip up large amounts of cash, you may be unsure as to how the different parts of your brain would respond in the event that you did see someone tearing valuable banknotes into tiny, worthless shreds. A new study may help you predict what would happen.

The study is called ‘How the Brain Responds to the Destruction of Money’. It tells how the brains of twenty Danish persons, all of them adults with no history of psychiatric or neurological disease, responded as they watched videos of somebody destroying lots of Danish money.

If you are not Danish, you might now expect that your brain would respond in rather the same way, were this to involve your own native currency (pounds, euros, dollars, or whatever). The study – performed by Uta Frith and Chris Frith of University College London, together with Joshua Skewes, Torben Lund, and Andreas Roepstorff of Aarhus University, Denmark, and Cristina Becchio of the University of Turin, Italy – makes no specific claims for non-Danish brains or money, however.

Here, in the scientists’ words, is what the volunteers saw: ‘A series of videos in which different actions were performed on actual banknotes with a value of either 100 Kroner (approximately 13 euro/18 US dollar) or 500 Kroner (approximately 67 euro/91 US dollar), or on valueless pieces of paper of the same size ... We contrasted actions that were appropriate to money (folding or looking at valuable notes or valueless paper) and actions that were inappropriate (tearing or cutting notes or paper).’

The Danes had their heads inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner (fMRI), which recorded some of their brain activity. The researchers also asked each volunteer some questions, including ‘How did it make you feel?’ All of this, says the document, ‘confirmed that participants felt less comfortable during observation of destroying actions performed on money’. An additional finding: the volunteers felt more ‘aroused’ when watching anything happen to money than when watching the same things happen to worthless paper.

The scientists find the brain scans to be especially interesting. The activity patterns, they say, are similar to something they’ve seen before: the ‘use of concrete tools, such as hammers or screwdrivers, has been associated with activation of a left hemisphere network including the posterior temporal cortex, supramarginal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, and lateral precuneus. Here we demonstrate that observing bank notes being cut up or torn, a critical violation of their function, elicits activation within the same temporo-parietal network. Moreover, this activation is the greater the higher the value of the banknote.’

They caution that the story must be more complex, that your brain probably regards money in several – differing – ways. They note, for example, the existence of published studies that ‘suggest that money can also act as a drug’.

Team member Chris Frith, by the way, was part of a group that gathered evidence about the brains of London taxi drivers being more highly developed than those of their fellow citizens. That study’s findings, honoured with the 2003 Ig Nobel Prize in medicine, appear to be unrelated to these later cautions.

Becchio, Cristina, Joshua Skewes, Torben E. Lund, Uta Frith, Chris Frith, and Andreas Roepstorff (2011). ‘How the Brain Responds to the Destruction of Money.’ Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 4 (1): 1–10.

Lea, Stephen E. G., and Paul Webley (2006). ‘Money as Tool, Money as Drug: The Biological Psychology of a Strong Incentive.’ Behavioral and Brain Sciences 29: 161–209.

Maguire, Eleanor, David Gadian, Ingrid Johnsrude, Catriona Good, John Ashburner, Richard Frackowiak, and Christopher Frith (2000). ‘Navigation-Related Structural Change in the Hippocampi of Taxi Drivers.’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97 (8): 4398–403.

The Invisible Hook of Pirate Economics

Pirates are a practical lot, at least in theory. The theory was supplied in 2007 by Peter T. Leeson, an assistant professor of economics at West Virginia University. He is of the opinion that pirates pioneered some basic economics.

In a study called ‘Pirational Choice: The Economics of Infamous Pirate Practices’, Leeson ‘investigates the internal governance institutions of violent criminal enterprise by examining the law, economics, and organization of pirates’. These were the classical pirates of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, especially those who practised professionally in and around the West Indies and in the waters around Madagascar. Leeson’s study appeared before chestsful of information began to surface in 2008 and 2009 in Wall Street, in the City of London, and at other romantic places where peril and opportunity drive many a captain of finance to pursue plunder.

‘Pirate governance created sufficient order and cooperation to make pirates one of the most sophisticated and successful criminal organizations in history’, writes Leeson. ‘To effectively organize their banditry, pirates required mechanisms to prevent internal predation, minimize crew conflict, and maximize piratical profit.’

Pirates, he argues, invented a system of checks and balances ‘to constrain captain predation’, and devised democratic constitutions to ‘create law and order’ among themselves. ‘Remarkably,’ points out Leeson, ‘pirates adopted both of these institutions before the United States or England.’

These pirate practices of the past now read like a ‘best practices’ primer on economics and finance. Successful buccaneers learned how to manage organizational growth: ‘Many pirate crews were too large to fit in one ship. In this case they formed pirate squadrons ... Multiple pirate ships often joined for concerted plundering expeditions. The resulting pirate fleets could be massive.’ They recognized that the big pirates had to be restrained from completely plundering the treasures of the little pirates under their command. Leeson uses simplified mathematical models to explain how this was achieved. ‘Consider a pirate ship of complete but imperfect information with a captain and two “factions” of ordinary pirates that together comprise the ship’s crew’, he says. ‘The captain moves first and decides whether to prey on the crew or not. If he preys on both factions simultaneously, they join together to overthrow him, so this is not an option he entertains. He can only prey on one faction at a time.’

The study works out the theoretical consequences, and summarizes them in two graphs captioned ‘The Threat of Captain Predation’ and ‘Piratical Checks and Balances: Constraining Captain Predation’. Examining the lines that connect the various nodes, one can follow the workaday machinations of pirate economic life, and see how these resolve into multiple equilibria and a collection of expected ‘payoffs’.

A note on sources from ‘Pirational Choice’

One sees at a glance how organizations of pirates come (in Leeson’s theory) to restrain or deflect themselves from destroying their own organizations. They enable themselves to keep working for the greater, more effective plunder of the larger, non-pirate community.

Leeson, Peter T. (2010). ‘Pirational Choice: The Economics of Infamous Pirate Practices.’ Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 76 (3): 497–510.

–– (2007). ‘Trading with Bandits.’ Journal of Law and Economics 50 (2): 303–21.

–– (2009). ‘The Invisible Hook: The Law and Economics of Pirate Tolerance.’ New York University Journal of Law and Liberty 4: 139–71.

––, and C. Coyne. ‘The Economics of Computer Hacking.’ Journal of Law, Economics and Policy 1(2) 2006: 511–32.

May We Recommend

‘How Smart Are the Smart Guys? A Unique View from Hedge Fund Stock Holdings’

by John M. Griffin and Jin Xu (published in the Review of Financial Studies, 2009)

The authors, at the University of Texas at Austin and Zebra Capital Management, report: ‘We provide the first comprehensive examination of hedge funds’ long-equity positions and the performance of these stock holdings ... Overall, our study raises serious questions about the proficiency of hedge fund managers.’

Rock, Paper, Monkeys

Among scholars of the game of rock-paper-scissors, only a tiny minority also study monkeys. This fact, by itself, may explain why no studies were published until 2005 about what happens when monkeys play rock-paper-scissors.

Daeyeol Lee, Benjamin P. McGreevy, and Dominic J. Barraclough of the University of Rochester, in New York, wrote that first, and so far the only, report on the subject: ‘Learning and Decision Making in Monkeys during a Rock-Paper-Scissors Game’. Lee, the lead author, has since moved to Yale University, where he is an associate professor of neurobiology.

The test subjects were male rhesus monkeys. No one explained to them the rules of the game: that rock breaks scissors, scissors cut paper, paper covers rock. The scientists wanted to see whether and how the monkeys would learn from the brute experience of playing game after game after game. Whenever a monkey did well, it got a sudden, sweet reward: a little drop of juice after each tie, two drops after each win. It received nothing – not even faint boos – after a loss.

For reasons unstated, the scientists chose not to use real rocks, paper, or scissors. Instead, they rigged a computer to display crude patterns of dots and circles. Different patterns represented a rock, a sheet of paper, and a pair of scissors. The monkeys were not informed as to which symbol stood for what object.

The monkeys were treated in a manner that is familiar to many hard-core computer gamers. Each sat in a chair, facing a monitor that flashed the symbols for rock, paper, and scissors. Rather than being asked to make the traditional physical gesture for rock, paper, or scissors, the monkey was expected to cast its gaze towards the symbol of its choice. The scientists tracked each monkey’s eye movements, using a German-manufactured Thomas-ET49 high-speed video-based eye-tracking machine, and digitally recorded the entire sequence of each monkey’s choices.

There were only two monkeys. They worked hard.

One monkey played rock-paper-scissors for forty-one days, making a total of 87,200 choices, an average of 2127 rounds every day. The other monkey played for fifty-two days, making a total of 82,661 choices, an average of 1589 rounds per day. Over the long haul, each monkey chose paper about as often as it picked scissors. Both monkeys displayed a slightly irrational aversion to rocks.

The scientists used economics theory to critique the overall performance, saying: ‘Each animal displayed an idiosyncratic pattern substantially deviating from Nash equilibrium.’ The Nash equilibrium was conceived by John Forbes Nash, who was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1994 for his ‘pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games’. He was also the subject of the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind.

Because only two monkeys were tested, Daeyeol et al. admitted that it ‘was difficult to conclude’ exactly which strategies a monkey uses to play the game. ‘This’, they write, ‘remains to be investigated in future studies.’

Lee, Daeyeol, Benjamin P. McGreevy, and Dominic J. Barraclough (2005). ‘Learning and Decision Making in Monkeys During a Rock-Paper-Scissors Game.’ Cognitive Brain Research 25 (2): 416–30.

Soviet Underwear Read

Olga Gurova studies the cultural history of underwear in the Soviet Union. ‘When I am talking about Soviet underwear’, she says, ‘I mean the underwear that appeared after the 1917 Revolution.’

Gurova is based at the Academy of Finland department of social research. In 2005–06, she spent a year in the US as a Fulbright fellow, and her public lectures helped to fill the information gap that developed during the Cold War.

In the 1920s, Soviet magazines touted a ‘regime of cleanliness’ for the proletariat. ‘Underwear’, explains Gurova, ‘was a compulsory part of that regime.’ A goal was established: everyone should have at least two sets of underwear, and should change sets at least once every seven to ten days. Mass production was cranked up, underclothing the populace in officially healthy, comfortable, hygienic long johns, boxers, undershirts, and bras. Gurova’s research shows that most of these items were ‘spacious’, and that ‘there was no big difference in design between male and female underclothes’.

Having pored over masses of documentation, Gurova infers that during the 1920s ‘Soviet underwear was not about sex, it was about sport’. Sports outfits – T-shirts, shorts, and sleeveless shirts – became the basic prototypes. Petticoats, seen as bulky and old-fashioned, faded from the scene, as did corsets. Underwear design quickly adapted to better serve Soviet women’s wide-ranging physical activities in the factory and the kitchen. In contrast to most European countries, reports Gurova, ‘the Soviet revolution canceled corsets and dressed women in bras more quickly’.

Gurova hypothesizes that, after the 1920s, there were three major periods in the history of Soviet underwear. The 1930s and 1940s were characterized by a Joseph Stalin speech, in 1935, proclaiming that Soviet life was becoming more abundant and joyful. Women’s underwear became somewhat feminine. For both sexes, undergarments could now be in certain colours. According to Gurova: ‘If previously they were white in color, according to hygienic reasons, later they become black, vinous, khaki or dark blue, and the explanation was the opposite than previous: dark colors become dirty slower.’

In the 1950s and 1960s, Premier Nikita Khrushchev increased Soviet interaction with other countries. Clothing styles were on Soviet minds. Soviet stores offered a wider, if not quite dizzying, array of consumer items. Soviet underwear became ‘a means of personal expression’.

The final period, the 1970s and 1980s, was marked by consumer goods shortages – and by a government campaign against obesity, with the slogan ‘To be plump is no good’. For many citizens, Gurova says, ‘it was hardly possible to buy undergarments that fitted well’.

It was here that the Soviet peoples showed their resilience. Gurova says that ‘manipulations with clothes at home became very popular: people sewed clothes, repaired them, and constructed new clothes from the old ones ... The Soviet man overcame the shortage, personified and privatized those standard clothes.’

These are the barest facts. Dr Gurova plans to cover them more fully with a book.

Gurova, Olga (2005). ‘Making of the Body: Cultural History of Underwear in Soviet Russia.’ Paper presented at the Russian, East European, and Eurasian Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 29 November.

In Brief

‘How Hello Kitty Commodifies the Cute, Cool, and Camp: “Consumutopia” Versus “Control” in Japan’

by Brian J. McVeigh (published in the Journal of Material Culture, 2000)

Evidence: Hello Kitty ‘bankbook and bank card’

Foucault on Management

Of all the football leagues for all the players in the world, the Australian Football League is the first to sponsor research that overtly applies the work of the French philosopher Michel Foucault.

Australian football is not soccer, nor is it American football. It is, fans and players like to point out, based on a different philosophy from anything else that answers to the name ‘football’. The Australian game even answers to its own, special nickname: footy. Australian behaviourists Peter Kelly and Christopher Hickey elucidate one aspect of the game’s philosophy in a study they call ‘Foucault Goes to the Footy: Professionalism, Performance, Prudentialism and Playstations in the Life of AFL Footballers’.

They went public with their work in 2004, when both were based at Australia’s Deakin University. Kelly has since moved to Monash University. He is also an honorary senior fellow at the University of Hull, UK. Both men are conversant with the thoughts of Michel Foucault, the bespectacled, bald philosopher who died in 1984, the year the Essendon Bombers won the footy championship, coming from four goals behind at the three-quarter mark of the ultimate game to decimate the defending champions, Hawthorn Hawks.

Foucault famously said, ‘Madness, death, sexuality, crime; these are the subjects that attract most of my attention.’ Several million footy-mad Australians would say much the same, be they supporters of Geelong, St Kilda, Adelaide, Carlton, Collingwood, or any of the eleven other clubs in the Australian Football League.

Kelly and Hickey say their research is ‘informed by Foucault’s later work on the care of the Self to focus on the ways in which player identities are governed by coaches, club officials, player agents and the AFL Commission/Executive; and the manner in which players conduct themselves in ways that can be characterised as professional – or not’.

That is a mouthful. It comes down to using Foucault’s philosophical ideas to help footy clubs choose players who will be worth the clubs’ substantial recruitment and salary investment.

The ideas are drawn primarily from Foucault’s ‘The Ethics of the Concern for Self as a Practice of Freedom’ and ‘Subjectivity and Truth’, essays he wrote late in life, during the period when the Australian Football League was still calling itself the Victorian Football League.

Then, player salaries were lower and footy clubs were almost carefree in their risk-management practices. Nowadays, the write-off cost of a defective or disruptive footy player is bigger, and thus so are the worries of prudent footy executives. Foucault helps them tackle those worries.

Elsewhere, the business community has been, on the whole, slow to adopt Foucault’s contributions to the philosophy of accounting. But the Australian Football League has built itself a platypus of a game by incorporating odd elements from the most unexpected places. It is unafraid to throw something different – even a dead French intellectual icon – into its business plans.

Kelly, Peter, and Christopher Hickey (2004). ‘Foucault Goes to the Footy: Professionalism, Performance, Prudentialism and Playstations in the Life of AFL Footballers.’ Paper presented at the TASA Annual Conference, Latrobe University, December.

A Good Head Shape for Business

A new line of American-British research suggests that the shape of a chief executive officer’s head can indicate how well his firm will prosper. The shape also predicts whether or not the chief executive will act immorally.

The research offers a mathematical tool that financial analysts can add to their professional kit bag: the chief executive officer’s facial width-to-height ratio. The ‘chief executive facial WHR’, for short. The research and its financial implications are outlined in a study called ‘A Face Only an Investor Could Love: CEOs’ Facial Structure Predicts Their Firms’ Financial Performance’, to be published in the journal Psychological Science.

The authors, Elaine Wong and Michael Haselhuhn at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and Margaret Ormiston at London Business School, explain the significance of their work. Prior researchers, they say, failed ‘to empirically identify physical traits that predict leadership success’ or predict ‘the ability of leaders to achieve organizational goals’.

Their discovery, in their view, constitutes a breakthrough: ‘We identify a specific physical trait, facial structure, of leaders that correlates with organizational performance. Specifically, chief executive officers with wider faces (relative to facial height) achieve superior firm financial performance.’

The story is not always that simple, the researchers caution, nor is it guaranteed: ‘The relationship between chief executive facial structure and financial performance is moderated by the decision-making dynamics of the leadership team.’

Wong, Haselhuhn, and Ormiston painstakingly examined the financial performance and chief executive facial measurements of General Electric, Hewlett-Packard, Nike, and fifty-two other publicly traded Fortune 500 firms for the period from 1996 through 2002. The companies are big, averaging $38 billion in annual sales and about 120,000 employees.

The researchers obtained chief executive facial photos from the Internet, using these as raw data from which to calculate each chief executive facial WHR. They looked up each firm’s return on assets (in financial industry shorthand, the ROA), using that as the measure of the company’s financial performance.

Wong and Haselhuhn spell out their logic in a study called ‘Bad to the Bone: Facial Structure Predicts Unethical Behaviour’, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B in 2011. They tell of experiments conducted on students, which showed ‘that men with wider faces (relative to facial height) are more likely to explicitly deceive their counterparts in a negotiation, and are more willing to cheat in order to increase their financial gain’.

They explain the mechanism that might make this happen. Prior research indicated that wide-faced men are ‘associated with more aggressive behaviour’. If ‘observers respond to facial cues by deferring to men whom they perceive to be aggressive based on their facial WHR, these men may find it easier to take advantage of others. Similarly, if men with greater facial WHRs are treated in ways that make them feel more powerful, this may foster a psychological sense of power, which then affects ethical judgement and behaviour.’

The facial indicators, say the researchers, are more reliable in men than in women.

The American Psychological Association, which is publishing the CEO study, issued a press release that finishes with this warning: ‘Don’t run out and invest in wide-faced CEOs’ companies, though. Wong and her colleagues also found that the way the top management team thinks, as reflected in their writings, can get in the way of this effect. Teams that take a simplistic view of the world, in which everything is black and white, are thought to be more deferential to authority; in these companies, the CEO’s face shape is more important. It’s less important in companies where the top managers see the world more in shades of gray.’

Wong’s work reinforces an ancient and reluctantly treasured belief: that having a good head on your shoulders does not, by itself, ensure success.

Wong, Elaine M., Margaret E. Ormiston, and Michael P. Haselhuhn (2011). ‘A Face Only an Investor Could Love: CEOs’ Facial Structure Predicts Their Firms’ Financial Performance.’ Psychological Science 22 (12): 1478–83.

Haselhuhn, Michael P., and Elaine M. Wong (2011). ‘Bad to the Bone: Facial Structure Predicts Unethical Behaviour.’ Proceedings of the Royal Society B online, http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2011/06/29/rspb.2011.1193.

Some Psychology of the Fruit Machine

It’s hard to get good payoffs from slot machines, yes. But it’s also hard to get good information from slot-machine gamblers, and that made things awkward for British psychologists Mark Griffiths of Nottingham Trent University and Jonathan Parke of Salford University. They explained the issue in a monograph entitled ‘Slot Machine Gamblers: Why Are They So Hard to Study?’

Griffiths and Parke published their report in the Electronic Journal of Gambling Issues. ‘We have both spent over 10 years playing in and researching this area’, they wrote, ‘and we can offer some explanations on why it is so hard to gather reliable and valid data.’

Here are three from their long list.

FIRST, gamblers become engrossed in gambling. ‘We have observed that many gamblers will often miss meals and even utilise devices (such as catheters) so that they do not have to take toilet breaks. Given these observations, there is sometimes little chance that we as researchers can persuade them to participate in research studies.’

SECOND, gamblers like their privacy. They ‘may be dishonest about the extent of their gambling activities to researchers as well as to those close to them. This obviously has implications for the reliability and validity of any data collected.’

THIRD, gamblers sometimes notice when a person is spying on them. ‘The most important aspect of non-participant observation research while monitoring fruit machine players is the art of being inconspicuous. If the researcher fails to blend in, then slot machine gamblers soon realise they are being watched and are therefore highly likely to change their behavior.’

Griffiths is one of the world’s most published scholars on matters relating to the psychology of slot-machine gamblers, with at least twenty-seven papers that mention so-called fruit machines, so-called for their bounty of cherries, oranges, and other juicy prizes. (It’s helpful to note that, in the UK, games of pure chance are not allowed, and so fruit machines require some element of ‘skill’; Griffiths and Parke don’t seem to obsess about the varied nomenclature.)

Griffith’s titles range from 1994’s appreciative ‘Beating the Fruit Machine: Systems and Ploys Both Legal and Illegal’ to 1998’s admonitory ‘Fruit Machine Gambling and Criminal Behaviour: Issues for the Judiciary’. Women get special attention (‘Fruit Machine Addiction in Females: A Case Study’), as do youths (‘Adolescent Gambling on Fruit Machines’ and several other monographs). There is the humanist perspective (‘Observing the Social World of Fruit-machine Playing’) as well as that of the biomedical specialist (‘The Psychobiology of the Near Miss in Fruit Machine Gambling’). The International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction ran a paean from a researcher who said: ‘In the problem gambling field we don’t exhibit the same adulation as music fans for their idols but we have our superstars and for me, Mark Griffiths is one.’

Griffiths and Parke collaborate often. (Strangers to their work might wish to begin by reading ‘The Psychology of the Fruit Machine’.) Their fruitful publication record reminds every scholar that, even when a subject is difficult to study, persistence and determination can yield a rewarding payoff.

Parke, Jonathan, and Mark Griffiths (2002). ‘Slot Machine Gamblers: Why Are They So Hard to Study?’ eGambling: Electronic Journal of Gambling Issues 6.

McKay, Christine (2007). ‘A Luminary in the Problem Gambling Field: Mark Griffiths.’ International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 5 (2): 117–22.

Griffiths, Mark. (1994). ‘Beating the Fruit Machine: Systems and Ploys Both Legal and Illegal.’ Journal of Gambling Studies 10: 287–92.

Griffiths, Mark, and Paul Sparrow (1998). ‘Fruit Machine Gambling and Criminal Behaviour: Issues for the Judiciary.’ Justice of the Peace 162: 736–39.

Griffiths, Mark. (2003). ‘Fruit Machine Addiction in Females: A Case Study.’ eGambling: Electronic Journal of Gambling Issues 8.

–– (1996). ‘Adolescent Gambling on Fruit Machines.’ Young Minds Magazine 27: 10–11.

–– (1996). ‘Observing the Social World of Fruit-machine Playing.’ Sociology Review 6 (1): 17–18.

–– (1991). ‘The Psychobiology of the Near Miss in Fruit Machine Gambling.’ Journal of Psychology 125: 347–57.

––, and Jonathan Parke (2003). ‘The Psychology of the Fruit Machine.’ Psychology Review 9 (4): 12–16.

May We Recommend

‘Physiological Arousal and Sensation-Seeking in Female Fruit Machine Gamblers’

by K. R. Coventry and B. Constable (published in Addiction, 1999)

The authors, who are at the University of Plymouth, UK, conclude: ‘Gambling alone is not enough to induce increases in heart rate levels for female fruit machine gamblers; the experience of winning or the anticipation of that experience is necessary to increase heart rate levels.’

The Value of Perfume for the Poor

What do destitute people have in mind when they haggle for famous-name perfume? Luuk van Kempen attacked the question head-on. He describes his experiment, and his thinking, in a report called ‘Are the Poor Willing to Pay a Premium for Designer Labels? A Field Experiment in Bolivia’.

Van Kempen, who is based at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, is trying to get at a deeper question: ‘Why do the poor buy status-intensive goods, while they suffer from inadequate levels of basic needs satisfaction?’ His study, which appears in the journal Oxford Development Studies, proceeds in social-scientific fashion, listing each of his assumptions, and shaking each one to see whether it is true.

FIRST QUESTION: Will impoverished Bolivians bargain for designer-label perfume? To find out, van Kempen had them play a what-if game known as a Becker-DeGroot-Marschak elicitation scheme. ‘Even subjects who have received little formal education’, he explains, ‘should be able to understand the procedure.’ Indeed, 104 residents of a poor neighbourhood in the city of Cochabamba understood the procedure well enough to quarrel with van Kempen over the price of perfumes.

SECOND QUESTION: How does one know this neighbourhood was poor? From the lack of safe water and of good sanitation facilities. The facilities ‘often consisted of one single latrine, were mostly shared among seven to 10 families’. Van Kempen explains that, for academic purposes, this had its benefits: ‘The experiment provided an implicit test of Maslow’s hierarchy-of-needs [theory], which suggests that people do not indulge in symbolic consumption, i.e. the acquisition of goods that satisfy belongingness and status needs, as long as “basic needs” are not satisfied.’

THIRD QUESTION: Is it reasonable to assume that a lack of access to safe water and sanitation truly indicates poverty? Yes, van Kempen concludes, citing a 2001 study of a different part of the city, which also lacked water and sewers. In that neighbourhood, eighty-seven percent of the population had incomes averaging about £1, or $1.80, a month. ‘Hence’, he says, ‘lack of access to basic services is a reasonably good proxy for income poverty.’

The main part of the study is titled ‘The Logo Premium: Do the Poor See Beyond Their Nose?’ This is where van Kempen describes his experiment. It involved bottles of perfume, some with a Calvin Klein label, others without. The perfume inside all the bottles smelled – and was – the same. Why Calvin Klein? ‘Because it is one of the best-known designer brands in Bolivia.’

Each poor person got to choose which perfume to buy – the Calvin Klein or the generic alternative – and bargain over the price she or he would pay for one versus the other.

About forty percent of these extremely low-income Bolivians were willing to pay extra for the designer name. What, statistically, was in their minds? Social caché, says van Kempen, the ability to walk with their noses in the air, regardless of what they might smell there.

Van Kempen, Luuk (2004). ‘Are the Poor Willing to Pay a Premium for Designer Labels? A Field Experiment in Bolivia.’ Oxford Development Studies 32 (2): 205–24.

Extreme Speed Writing

Philip M. Parker is the world’s fastest book author, and given that he had been at it for only five years or so when I contacted him in 2008, and already had more than 85,000 books to his name, he is likely the most prolific, as well as the most titled.

Parker is also the most wide-ranging of authors – the phrase ‘shoes and ships and sealing wax, cabbages and kings’ is not half a percent of it. Nor are these particular subjects foreign to him. He has authored some 188 books related to shoes, ten about ships, 219 books about wax, six about sour red cabbage pickles, and six about royal jelly supplements.

To begin somewhere, let’s note that Parker is the author of the book The 2007–2012 Outlook for Bathroom Toilet Brushes and Holders in the United States, which is 677 pages long, sells for £250/$495, and is described by the publisher as a ‘study [that] covers the latent demand outlook for bathroom toilet brushes and holders across the states and cities of the United States’. (A later edition, covering 2009–2014, retails for £495/$795. Further Parkerian volumes and updated pricing can be expected to appear automatically in the years, decades, and centuries beyond.)

Here’s a minuscule (compared to the entire, ever-growing list) sampling of Philip M. Parker titles:

The 2007–2012 World Outlook for Rotary Pumps with Designed Pressure of 100 P.s.i. or Less and Designed Capacity of 10 G.p.m. or Less

Avocados: A Medical Dictionary, Bibliography, and Annotated Research Guide

Webster’s English to Romanian Crossword Puzzles: Level 2

The 2007–2012 Outlook for Golf Bags in India

The 2007–2012 Outlook for Chinese Prawn Crackers in Japan

The 2002 Official Patient’s Sourcebook on Cataract Surgery

The 2007 Report on Wood Toilet Seats: World Market Segmentation by City

The 2007–2012 Outlook for Frozen Asparagus in India

Parker is a professor of management science at INSEAD, the international business school based in Fontainebleau, France. Professor Parker is no dilettante. When he turns to a new subject, he seizes and shakes it till several books, or several hundred, emerge. About the outlook for bathroom toilet brushes and holder, Parker has authored at least six books. There is his The 2007–2012 Outlook for Bathroom Toilet Brushes and Holders in Japan, and also The 2007–2012 Outlook for Bathroom Toilet Brushes and Holders in Greater China, and also The 2007–2012 Outlook for Bathroom Toilet Brushes and Holders in India, and also The 2007 Report on Bathroom Toilet Brushes and Holders: World Market Segmentation by City.

When I first encountered Parker’s output, Amazon.com offered 85,761 books authored by him. Parker himself said the total was well over 200,000. The number was then and is (even as you read these words, whenever you read them, possibly even if Professor Parker has been gone for decades or centuries) probably still on the rise.

How is this all possible? How does one man do so much? And why?

Parker created the secret to his own success. He invented what he calls a ‘method and apparatus for automated authoring and marketing’ – a machine that writes books. He says it takes about twenty minutes to write one.

Fig. 1 of 13 from ‘Method and Apparatus for Automated Authoring and Marketing’ – ‘the embodiment of the present invention’

Turn to page 16 of his patent, and you will see him answer the question, ‘And why?’

Parker quotes a 1999 complaint, waged by The Economist magazine, that publishing ‘has continued essentially unchanged since Gutenberg. Letters are still written, books bound, newspapers mostly printed and distributed much as they ever were.’

‘Therefore’, says Parker, ‘there is a need for a method and apparatus for authoring, marketing, and/or distributing title materials automatically by a computer.’ He explains that ‘Further, there is a need for an automated system that eliminates or substantially reduces the costs associated with human labor, such as authors, editors, graphic artists, data analysts, translators, distributors, and marketing personnel.’

The book-writing machine works simply, at least in principle. First, one feeds it a recipe for writing a particular genre of book – a tome about crossword puzzles, say, or a market outlook for products, or maybe a patient’s guide to medical maladies. Then hook the computer up to a big database full of info about crossword puzzles or market information or maladies. The computer uses the recipe to select data from the database and write and format it into book form.

Nothing but the title need actually exist until somebody places an order – typically via an online, automated bookseller. At that point, a computer assembles the book’s content and prints up a single copy.

Among Parker’s one hundred best-selling books (as ranked by Amazon) one finds surprises. His fifth-best seller in 2008 was Webster’s Albanian to English Crossword Puzzles: Level 1. Bestseller No. 21: The 2007 Import and Export Market for Seaweeds and Other Algae in France. No. 66 is the aforementioned The 2007–2012 Outlook for Chinese Prawn Crackers in Japan. And rounding out the list, at No. 100, is The 2007–2012 Outlook for Edible Tallow and Stearin Made in Slaughtering Plants in Greater China.

Parker appears also to be enthusiastic about books authored the old-fashioned way. He has already written five of them.

Parker, Philip M. (2005). ‘Method and Apparatus for Automatic Authoring and Marketing.’ US Patent No. 7,266,767, 31 October.

The Hundred Trillion Dollar Book

Gideon Gono, author of the barnstorming book Zimbabwe’s Casino Economy – Extraordinary Measures for Extraordinary Challenges, displays a rare, perhaps unique kind of scholarly reserve. He is a scholar, with a PhD from Atlantic International University, a mostly distance-learning institution based in the US, with a website that proclaims ‘Atlantic International University is not accredited by an accrediting agency recognized by the United States Secretary of Education’. And he has reserve, or rather Reserve, with a capital ‘R’. Since December 2003, Gideon Gono has been the governor of Zimbabwe’s Reserve Bank. His term expires in 2013.

In 2009, Gono was awarded the Ig Nobel Prize in mathematics. The Ig Nobel citation lauds him for giving people a simple, everyday way to cope with a wide range of numbers – from the very small to the very big – by having his bank print bank notes with denominations ranging from one cent ($.01) to one hundred trillion dollars ($100,000,000,000,000).

During 2007 and 2008, Zimbabwe’s inflation rate rose past Olympian heights: topping 231 million percent, by Gideon Gono’s reckoning; and reaching 89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000 percent, according to a study done by Dr Steve H. Hanke of Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Maryland, and the Cato Institute.

The book explains that every larger, richer country than Zimbabwe will face the same problems, at which time they will appreciate Gono’s extraordinary skill at meeting such extraordinary challenges. Gono modestly shares the credit, writing on the very first page: ‘I am especially indebted to my principal, President Robert Mugabe’.

Gono’s talents were spotted by other influential persons. ‘I was both humbled and surprised’, he writes, ‘to get an approach from [US] Ambassador [to Zimbabwe James] McGee on 25 July 2008 with an offer which he said was from President George W. Bush and Secretary Condoleeza Rice and the President of the World Bank for me to take a position in Washington as a Senior Vice President of the World Bank.’

He confides that later, ‘my staff and I were amused to see the steady mushrooming of rather shameless news stories in some quarters of the Western Press and its allied media claiming that I had approached the United States authorities seeking their help to secure asylum for me and my family in some banana republic or that I somehow wanted to betray President Mugabe and Zimbabwe’s national leadership and to run away from Zimbabwe in the face of what was alleged to be the collapse of the economy and President Mugabe’s rule.’

Gono emphasizes the importance of sticking to one’s principles. ‘My team and I were guided by the philosophy’, he writes, that ‘where appropriate, short-term inflationary surges are a necessary cost to the achievement of medium to long-range growth in the economy.’

The book is, at heart, a 232-page literary fleshing-out of an eighteen-word statement issued by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe on 21 January 2008: ‘Blaming the Government, the Reserve Bank or the Governor all the time is unacceptable and will be met with serious consequences.’

Gono, Gideon (2008). Zimbabwe’s Casino Economy – Extraordinary Measures for Extraordinary Challenges. Harare: ZPH Publishers.

Trinkaus on Trolleys

Shopping carts are a window, however small, to our inner being.

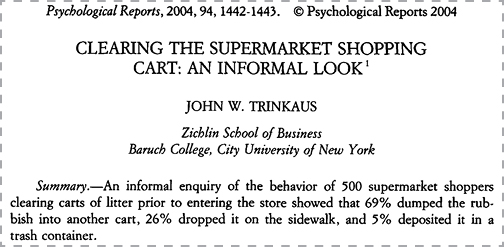

‘Some people entering supermarkets, to do their food shopping, seem to prefer to start their venture with a clean cart – one that is free of litter. However, many times a number of the available carts are not free of the leavings of previous shoppers, for example, store circulars, cash register receipts, shopping lists, plastic bags, produce remnants, facial tissues, and candy wrappers. Such folks, when finding that the cart at the end of the queue is not “clean”, face a decision: push the cart to the side and try the next one, use it anyway, or somehow get rid of the material in the cart. It is this third alternative that was looked at in this enquiry.’

Thus begins a report from academia’s expert on all things that grate and are small. John W. Trinkaus, a professor emeritus at New York City’s Zichlin School of Business, has turned his gimlet eye to the annoying little aspects of modern life.

Trinkaus won the 2003 Ig Nobel Prize in literature for publishing more than eighty studies of things that annoy him. A former engineer and an ever-curious student of human behaviour, he has personally gathered statistics about people who wear their baseball caps backwards, attitudes towards Brussels sprouts, the marital status of television quiz show contestants, pedestrians who wear sports shoes that are white rather than some other colour, swimmers who swim laps in the shallow end of the pool rather than the deep end, and shoppers who exceed the number of items permitted in a supermarket’s express checkout lane. And many, many other quirks of human behaviour. Today his oeuvre totals more than one hundred monographs.

The Trinkaus method is to observe, and then to produce a no-nonsense report, typically two or three pages long. Many of his publications show a deep interest in waiting, obstruction, and delay, as epitomized in his 1985 single-page ‘Waiting Times in Physicians’ Offices: An Informal Look’.

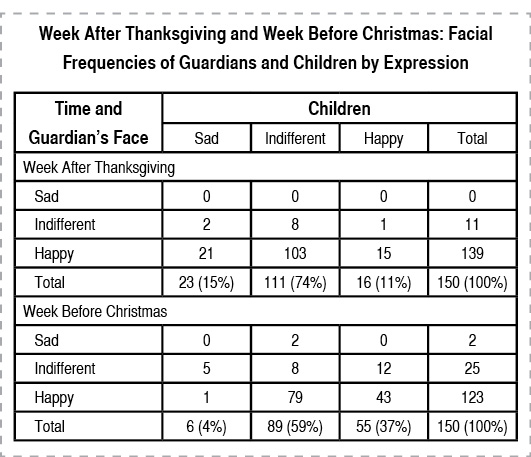

Waiting is also the subject in Trinkaus’s gift of a study ‘Visiting Santa: An Additional Look’, which he bestowed on us – all of us – in 2007. That was a sequel to the previous year’s ‘Visiting Santa: Another Look’, which built upon the work he described in the very first of his Santa-related studies, 2004’s ‘Santa Claus: An Informal Look’.

Each of these reports gives a cheerfully dreary look at the behaviour of children and their parents in a shopping mall. As the 2007 report describes it: ‘The observer [which is to say, Trinkaus] positioned himself unobstrusively a short distance away from a single line of children and guardians advancing to visit with Santa Claus, in a place where the children’s and guardians’ facial expressions could be noted.’ The findings, he writes, are ‘consistent with the conclusions that the greater percentage of children appeared indifferent to their visit to Santa’. As in his previous investigations, many of the guardians did look excited, or at least looked like they were trying to look excited.

Trinkaus also shows a special fascination with people’s adherence to laws, regulations, and customs. His ‘Stop Sign Compliance: An Informal Look’, published in 1982, examined how many motorists did – and how many did not – come to a full stop at a particular street-corner. Trinkaus did follow-up studies at that same intersection in 1983 (‘Stop Sign Compliance: Another Look’), 1988 (‘... A Further Look’), 1993 (‘... A Follow-Up Look’), and 1997 ‘... A Final Look’). In yet another parallel series of studies, Trinkaus looked at drivers’ compliance with a traffic stoplight. Together, these document an unseemly, seemingly unstoppable rise in scofflawism.

To do his shopping cart research, Trinkaus lurked, in a professional manner, at a supermarket. He kept a close but, again, unobtrusive watch on people who entered the store. This all took place during the spring, ‘on weekdays when the weather was fair, during the hours of 0900 to 1600’. He paid attention only to those shoppers who cleared their carts of litter prior to doing their shopping. He found that ‘69% dumped the rubbish into another cart, 26% dropped it on the sidewalk, and 5% deposited it in a trash container.’

Trinkaus sees in these numbers a small warning sign to society: ‘Many people espouse such things as the virtues of the golden rule and brotherly love, but ... one might well wonder how much is rhetoric and how much is real. For example, how much social awareness is being exhibited by those folks leaving behind rubbish in their cart for others to cope with? Too, how much communal consciousness is being evidenced by those people who, when finding rubbish in a cart, shift the disposing problem to others?’ He says: ‘Understanding and measuring real-life, everyday situations, such as that recounted here, could possibly help in unfolding a better understanding of the make-up and operation of present day society.’

Trinkaus, John W. (2004). ‘Clearing the Supermarket Shopping Cart: An Informal Look.’ Psychological Reports 94: 1442–43.

–– (2007). ‘Visiting Santa: An Additional Look.’ Psychological Reports 101: 779–83.

The Strategic Jesus

A whole new side of Jesus is cropping up in the field of decision science, as a rising generation of scholars is taking Jesus to their collective, theoretic, strategic bosom. Their leader, by eminence and example, and perhaps by judicious application of strategy, is a highly promoted man of both intellect and action.

‘Jesus the Strategic Leader’, by Lt. Col. Gregg F. Martin of the US Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was published in the year 2000. It is fifty-one pages long. ‘This is not a religious study’, Colonel Martin writes, ‘it is a practical analysis. If one believes that Jesus was simply a man, and not, as Christians believe, part-man and part-God, then the study reveals how one of history’s greatest leaders led. If, on the other hand, one believes that Jesus was God in human form, then the study not only shows how a great human being practiced the art of leadership, but also how God chose to lead. In either case, the student or practitioner of leadership cannot go wrong.’

The report includes a drawing of Martin’s ‘pyramid model’ of Jesus the strategic leader. According to this model, Jesus is a pyramid, resting atop and partially intersecting God. God is a pyramid, too, but with a broader base. A third, inverted pyramid is supported atop Jesus’s pyramid. This third pyramid begins with what Martin calls the ‘Top Three’ disciples (Peter, James, and John) and broadens to include the other apostles, then the disciples and, topping everything, the masses.

‘

‘

The Strategic Jesus’ gives us succinct dictums: ‘Develop expertise, then use it with authority ... Choose your battles ... Delegate and power down.’

Colonel Martin left the War College not long after publication of his report. He went on to command the 130th Engineer Brigade of the US Army’s Fifth Corps, leading combat engineers before, during, and for more than a year after the invasion of Iraq. He has since returned to his homeland, been promoted to the rank of major general, and been appointed commandant of the War College, where a new generation of American miltary leaders can benefit from his Jesus-style strategic leadership.

Martin, Lt. Col. Gregg F. (2000). ‘Jesus the Strategic Leader.’ US Army War College strategic report, 5 April, http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADA378218.

Bored Meetings

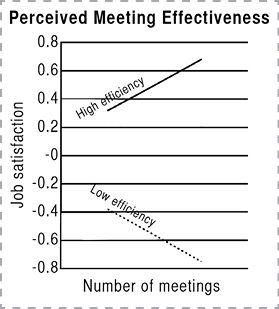

Do you believe, as someone somewhere perhaps does, that meetings, meetings, meetings, followed by more meetings, are altogether a good thing? If so, Alexandra Luong, of the University of Minnesota, Deluth, and Steven G. Rogelberg, of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, think you should think again. They say: ‘We propose that despite the fact that meetings may help achieve work-related goals, having too many meetings and spending too much time in meetings per day may have negative effects on the individual.’

Their report, published in the journal Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, begins with a somewhat brief recitation of the history of important research discoveries about meetings. Here is a capsule version of their tale.

DISCOVERY: The majority of a manager’s typical workday is spent in meetings. This was reported by an investigator named Mintzberg in 1973.

DISCOVERY: The frequency and length of meetings have grown considerably. So declared the team of Mosvick and Nelson in 1987.

DISCOVERY: A scientist named Zohar, in a series of reports published during the 1990s, found evidence that ‘annoying episodes’ – which are sometimes also known as ‘hassles’ – contribute to burnout, anxiety, depression, and other negative emotions. Zohar advanced a theoretical framework that may one day help explain why this is so.

DISCOVERY: In 1999, a scientist named Zijlstra ‘had a sample of office workers work in a simulated office for a period of two days in order to examine the psychological effects of interruptions. [They] were periodically interrupted by telephone calls from the researcher.’ This had what Zijlstra calls ‘negative effects’ on their mood.

Luong and Rogelberg used those and other discoveries as a basis for their own innovatively broad theory.

They devised a pair of hypotheses, educatedly guessing that:

- The more meetings one has to attend, the greater the negative effects; and

- The more time one spends in meetings, the greater the negative effects.

Then they performed an experiment to test their two hypotheses. Thirty-seven volunteers each kept a diary for five working days, answering survey questions after every meeting they attended and also at the end of each day. That was the experiment.

Figure: ‘Two-way interaction of number of meetings and perceived meeting effectiveness to predict job satisfaction’

The results speak volumes. ‘It is impressive’, Luong and Rogelberg write in their summary, ‘that a general relationship between meeting load and the employee’s level of fatigue and subjective workload was found’. Their central insight, they say, is the concept of ‘the meeting as one more type of hassle or interruption that can occur for individuals’.

Dr Rogelberg delivered this insight in a talk called ‘Meetings and More Meetings’, which he presented to a meeting at the University of Sheffield. He also does a talk called ‘Not Another Meeting!’, which was well received at two meetings in North Carolina and also at two meetings in Israel.

Luong, Alexandra, and Steven G. Rogelberg (2005). ‘Meetings and More Meetings: The Relationship Between Meeting Load and the Daily Well-Being of Employees.’ Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 9 (1): 58–67.

Rogelberg, S. G., D. J. Leach, P. B. Warr, and J. L. Burnfield (2006). ‘“Not Another Meeting!” Are Meeting Time Demands Related to Employee Well-being?’ Journal of Applied Psychology 91 (1): 83–96.

Corporate Tiers of a Clown

Ronald McDonald is not just a clown who hawks hamburgers and fries. According to two scholars writing in the journal Leadership Quarterly, Ronald McDonald is also a transformational corporate leader.

David M. Boje holds the Bank of America Endowed Professorship of Management at New Mexico State University. Carl Rhodes is an associate professor in the School of Management at the University of Technology in Sydney, Australia. Together they produced ‘The Leadership of Ronald McDonald: Double Narration and Stylistic Lines of Transformation’.

Boje and Rhodes put their case forthrightly. ‘The argument’, they say, ‘is that rather than just being a spokesperson or marketing device for the McDonald’s corporation, Ronald performs an important transformational leadership function.’ ‘We argue’, they argue, ‘that while Ronald is crafted by the actual leaders of McDonald’s, his leadership exceeds official corporate narratives because of the cultural meanings associated with his character as a clown.’

Clown figures employed by other companies are at best mere employees, at worst mere fictions. As measured by org charts, Mr McDonald towers above the other corporate clowns. Boje and Rhodes reveal that ‘since 2003, he has held the quasi-formal executive position of Chief Happiness Officer, and, on 16 April 2004, he became the Ambassador for an Active Lifestyle’.

Boje and Rhodes tell in detail how and why Mr McDonald entered the executive ranks. They then boil it all down to this: ‘McDonald’s corporate executives believed Ronald could do more than just be a figurehead “spokesclown” at “high-profile public relations stunts such as delivering Happy Meals to the United Nations.” [The Russian philosopher Mikhail] Bakhtin’s words apply to Ronald: “there always remains in him unrealized potential and unrealized demands”.’

Though the researchers may be too modest to suggest it, their Ronald McDonald analysis can be applied to other fields of inquiry. For example, it could help explain recent leadership trends in great nations.

Here are some McNuggets from the study:

Our analysis suggests that a new category of leader is needed; something called a ‘clown leader’. As Ronald takes on the ancient masks of rogue, clown, and fool, he integrates diverse forms of laughter (rogue destructive humor, clown merry deception, and fool’s right not to comprehend the system). It is this appropriation of a clown type by the world’s largest restaurant corporation that is central to its transformation. A method used to transform clowns into leaders is to represent them in adventures of misfortune which are overcome by their leadership powers ...

There is much reason to be skeptical about new forms of leadership that might enhance corporate power in a way that creates new forms of authoritarianism whose operations are far from transparent. This is even more salient for leadership such as Ronald’s, whose influence might not easily be noticed given his fictional character.

Boje, David M., and Carl Rhodes (2006). ‘The Leadership of Ronald McDonald: Double Narration and Stylistic Lines of Transformation.’ Leadership Quarterly 17 (1): 94–103.

In Brief

‘Vision of Integrated Happiness Accounting System in China’

by G. Cheng, Z. Xuand, and J. Xu (published by Acta Geographica Sinica, 2005)

A Calculus of Prostitution

There are many theories about prostitution. The theory devised by Marina Della Giusta, Maria Laura Di Tommaso, and Steinar Strøm is one of the few that involves partial differential equations. Sure, they could, if they wished, describe prostitution in words. But for scholars who want to explain prostitution, differential calculus may be the clearest language.

These three scholars, economists all, are based in the UK, Italy, and Norway, making this an international affair. Della Giusta teaches at the University of Reading, Di Tommaso at the University of Turin, and Strøm jointly at the University of Turin and the University of Oslo.

They make their case in a report published in 2007 in the Journal of Population Economics. It begins by summarizing the ways in which other economists explain prostitution. Here’s a summary of their summary: those other economists are wrong.

The other economists concentrate on gender, pay, and the ‘nature of forgone earning opportunities of prostitutes and clients’. But, say Della Giusta, Di Tommaso, and Strøm, those don’t count for much. What really matters is the economic role played by stigma and reputation. And the simplest, best way to explain that is with mathematics.

The concepts are as easy and familiar as a good street-corner prostitute:

U is your satisfaction. It’s what you, as a prostitute, really care about – the satisfaction you gain from selling your services. Economists like to call it ‘utility’, which is why they like to use the letter ‘U’.

L is the amount of leisure you have.

C is the amount of goods and services you, as a consumer, consume.

S is the amount of prostitution you, as a prostitute, sell to your customers.

w is the going price for prostitutes.

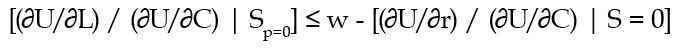

r is a measure of your reputation.

The whole situation, seemingly so complicated, simmers down to a nice partial differential equation. Here it is – Della Giusta, Di Tommaso, and Strøm’s rule of thumb for prostitutes. You, a prostitute, find it worthwhile to sell your prostitution services when:

That’s the poetic, simple way of putting it. But prostitution is by tradition considered vulgar, so the team also gives a vulgar, all-words description: ‘An individual will start to sell prostitution if the price for selling the first amount of prostitution, minus the costs of a worsened reputation for doing so, exceeds the shadow price of leisure evaluated at zero prostitution sold.’

That, in theory, is the story of prostitution. But it’s not the only one.

As with competition among prostitutes, competiton among economists who have theories of prostitution can be spirited. Lena Edlund, of Columbia University in New York, and Evelyn Korn, of Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in Germany, have also worked up a theory that uses partial differential equations. They call it, modestly, ‘A Theory of Prostitution’. Della Giusta, Di Tommaso, and Strøm cite Edlund and Korn’s theory – but say there are other theories that are ‘more sophisticated’.

Prostitution is a difficult, dangerous profession. In addition to all of their obvious hardships, prostitutes must also endure the cold, small knowledge that economists still argue as to exactly what, why, and how they do their work.

Della Giusta, Marina, Maria Laura Di Tommaso, and Steinar Strøm (2007). ‘Who’s Watching? The Market for Prostitution Services.’ Journal of Population Economics 22 (2): 501–16.

Edlund, Lena, and Evelyn Korn (2002). ‘A Theory of Prostitution.’ Journal of Political Economy 110: 181–214.