Eight

Exciting Injuries and Ills

In Brief

‘Taking Action on the Volume-Quality Relationship: How Long Can We Hide Our Heads in the Colostomy Bag?’

by Thomas J. Smith, Bruce E. Hillner, and Harry D. Bear (published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2003)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Misnomers of the mouth • The romance of proctology • Disco dangers • A huge Parisian tooth-yanker • Louis XIV’s missing teeth • Eat your mummy • Michael Jackson surgery • In pursuit of a wretched itch • Dr Bean’s fingernails • Tripping over a black cat • Unlubricated karaoke • The celebrated rectum of the Bishop of Durham

A Hot Potato

Dr Mahmood Bhutta’s greatest achievement – measuring the sound produced by a person with a hot potato in his mouth – has been overlooked in the flurry of attention given his newer study on whether sexual thoughts can trigger sneezing fits.

Bhutta practises surgery at Wexham Park Hospital, in Slough, UK. His paper, published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine under the title ‘Sneezing Induced by Sexual Ideation or Orgasm: An Under-Reported Phenomenon’, has brought acclaim to Bhutta and to his co-author and fellow sneezing-induced-by-sexual-ideation-or-orgasm expert Dr Harold Maxwell, a retired honorary senior lecturer and consultant psychiatrist formerly at West Middlesex University Hospital, in Isleworth. The paper brought an elevated level of reportage to a phenomenon that had appeared in formal medical reports only a handful of times, in 1875, 1872, and 1972. Trolling through the ailment-infested chat rooms of the Internet, Bhutta and Maxwell unearthed seventeen new cases of people who say they sneeze immediately after thinking about sex, and three others who complain or brag that they sneeze after experiencing an orgasm.

Back in 2006, Bhutta worked in the department of ear, nose, and throat, head and neck surgery at the Royal Sussex county hospital in Brighton. He and fellow Royal Sussex ear-nose-and-throat, head-and-neck surgery specialists George A. Worley and Meredydd L. Harries examined the phenomenon (unrelated to sexual ideation, orgasm, or sneezing) known as ‘hot potato voice’.

The study ‘“Hot Potato Voice” in Peritonsillitis: A Misnomer’ appeared in the Journal of Voice. ‘Voice changes are a well-recognized symptom in patients suffering from peritonsillitis’, the authors explain in the report. ‘The voice is said to be thick and muffled and is described as a “hot potato voice”, because it is believed to resemble the voice of someone with a hot potato in his or her mouth. There have been very few studies analysing the profile and characteristics of the voice changes in tonsillitis or peritonsillitis and none that have compared these changes with those that occur with a hot potato in the oral cavity.’

To remedy this lack of knowledge, the three doctors recruited two sets of volunteers. The first group comprised ten hospital patients whose suffering related to their tonsils. Each volunteer pronounced three particular vowel sounds, which the doctors recorded and subsequently analysed using special software. The second group was ten healthy hospital staffers, ‘with each of these participants placing a British new potato of approximately 50 grams in their oral cavity, warmed by microwave to a “hot” but not uncomfortable temperature’.

The doctors detected unmistakable differences. The unique sound of someone burdened with an actual potato, they explain, ‘is related to interference with the anterior tongue function from the physical presence of the potato’.

Bhutta, Mahmood F., George A. Worley, and Meredydd L. Harries (2006). ‘“Hot Potato Voice” in Peritonsillitis: A Misnomer.’ Journal of Voice 20 (4): 616–22.

Bhutta, Mahmood F., and Harold Maxwell (2008). ‘Sneezing Induced by Sexual Ideation or Orgasm: An Under-Reported Phenomenon.’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 101: 587–91.

Deep, Dark Romance

Of all the romance books ever written, which has the most surprising depths?

The Romance of Tristan and Iseult? No. The Romance of Isabel, Lady Burton? No.

The Romance of Pepperell, Being a Brief Account of the Career of Sir William Pepperell, Soldier, Pioneer, American Merchant and Developer of New England Industry, for Whom the Pepperell Manufacturing Company was Named, and the Towns of Saco and Biddeford in the State of Maine, wherein the First Manufacturing Unit of the Pepperell Company was Established? No.

No, none of those books approach the depths of Charles Elton Blanchard’s 1938 thriller, The Romance of Proctology.

Blanchard was a proctologist by trade and by temperament. He wrote some twenty books on the subject. The Romance of Proctology is his masterpiece.

Later authors were inspired by Blanchard’s élan. Emilio de los Ríos Magriñá, for one, is notable for his Color Atlas of Anorectal Diseases, published in 1980. But as its title implies, the book lacks romance.

Blanchard pours on the romance. His opening sentence is an irresistible come-on: ‘No one knows who was the first doctor to examine the rectal orifice of the human frame.’

The reader grows all quivery as Blanchard shows us history’s parade of charismatic proctologists, heroic actions, and frightening tools of the trade.

‘These pioneers were earnest seekers after proctological truth’, he writes in introducing Dr William Allingham of London. ‘Allingham believed in the value of linear cauterization using the Paquelin cautery for proctidentia recti. He claims he was the first (and possibly the last) to insert the whole hand into the rectum.’

The seventeenth-century physician Morgani receives special praise. Blanchard speaks of him on our behalf: ‘We are thankful to Morgani that in the midst of all his many researches he, of all the great names at Padua, looked into the human rectum, discovered and named its crypts and pillars.’

‘It is strange’, Blanchard reminds us, ‘how immortality in medicine is often gained by some very minor contribution. Morgani is remembered by the crypts and columns of the rectal outlet. Hilton by his “white line” which is seldom white in the living subject.’ He is writing about John Hilton of Guy’s Hospital, London – the John Hilton who was known as ‘anatomical John’ and who was made surgeon to Queen Victoria. Blanchard’s reverence for him is nearly boundless: ‘I would rather drop one tear on the grave of John Hilton than to place a costly wreath on the tomb of Napoleon.’

Blanchard tips his cap, too, to Dr Joseph M. Mathews of Louisville, Kentucky, of whom he writes: ‘Dr Mathews was much like Dr Allingham, jovial, talkative and yet rather sure of his opinions being right. He much preferred to be called “Rectal Specialist” than by any other high-sounding name. To him should go much credit for making proctology a specialty.’

There are, of course, many biological romance books. Anyone who enjoys Blanchard’s The Romance of Proctology can seek delight also in A. Radclyffe Dugmore’s The Romance of the Beaver, published in 1914.

Blanchard, Charles Elton (1938). The Romance of Proctology. Youngstown, Ohio: Medical Success Press.

Neuhauser, D. (2006). ‘Advertising, Ethics and the Competitive Practice of Medicine: Charles Elton Blanchard MD.’ Quality and Safety in Health Care 15: 74–75.

Catching Disco Fever

However serious researchers were about discotheques, most of them kept quiet about it for a long time. Then a glorious decade gave birth to two pools of disco studies. One describes injuries, illnesses, and other ills that should or could be blamed on discos and disco music. The other tells about a world of exciting disco-inspired and disco-enabled – in short, disco-fuelled – investigations.

A lone, curious voice, that of M. S. Swani of Birmingham, UK, sounded perhaps the first interested cry. In a letter dated 30 November 1974 published in the British Medical Journal, Dr Swani wrote: ‘Early deafness in young people as a result of exposure to excessive noise in “discos” must now be assuming epidemic proportions. The importance of this problem has been brought especially to my mind because an 18-year-old medical secretary, who has worked for me, has now been found to be suffering from this condition. If every general practitioner in the country had one such new case a year there would be 20,000 new cases in the country annually.’

Discos became popular in the 1960s and wildly so in the 1970s, but almost no formal disco-themed studies appeared until 1980. Thereafter, disco scholarship flourished.

One stream of reports, perhaps an indirect result of Swani’s secretary’s what-what-what-ing to her frustrated boss, explained that people who spend too much time listening to much-too-loud music become hard of hearing.

Around the world, doctors published reports raising other medical questions. Among the titles: ‘Effect of Discotheque Environment on Epileptic Children’ (UK, 1981); ‘Acute Central Cervical Cord Injury Due to Disco Dancing’ (Ireland, 1983); ‘The Dyspeptic Disco Dancer’, (Hong Kong, 1988); ‘Disco Fever: Epidemic Meningococcal Disease in Northeastern Argentina Associated with Disco Patronage’ (Argentina, 1988); and ‘Valsalva Retinopathy Associated with Vigorous Dancing in a Discotheque’ (Israel, 2007). Roller disco inspired its own sub-genre, with such titles as: ‘Roller Disco Neuropathy’ (USA, 1981); and ‘The Roller Discotheque – A Quickstep to the Hospital? An Analysis of 196 Accidents’ (Germany, 1985).

But it wasn’t just doctors. Disco opened exciting new worlds for everybody. I will mention just two of the studies that appeared in that breakthrough year, 1980. Margaret Doyle Pappalardo wrote her doctoral thesis, at Boston University in Massachusetts, on ‘The Effects of Discotheque Dancing on Selected Physiological and Psychological Parameters of College Students’, while graduate student, Bruce Taylor, at the University of Bergen, sought not the side-effects of disco, but its heart.

Taylor’s thesis, called ‘Shake, Slow, and Selection: An Aspect of the Tradition Process Reflected by Discotheque Dances in Bergen, Norway’, appeared in the journal Ethnomusicology. He interviewed patrons near the dance floor. ‘According to them’, Taylor wrote, ‘the most important principle is to follow the rhythm and the beat, but variation is also necessary, and a good dancer is interested in the dance as well as in his partner ... Conversations between strangers are begun, personal contact is achieved, and many of the guests who arrived alone are actively interested in leaving for home with a new acquaintance of the opposite sex.’

Even doctors manage, sometimes, to find some delight in disco, especially in describing its effects and after-effects. That seems evident in the phrasing of a case report called ‘The University Rollerdisco: An Unusual Cause of a Major Incident’, which appeared in the journal Injury Extra.

The co-authors play the role of raconteurs rather than traditional, stuffy medicos: ‘Rollerdiscos are associated with a high incidence of injury, as is binge drinking. On Valentine’s evening 2008, Liverpool University combined these two venerable pastimes at a student event, without informing local health services. Subsequently, emergency services were overwhelmed with Rollerdisco casualties and a “major incident” ... The event itself consisted of a newly laminated hall for roller skating, alcoholic drink promotions and a 1980s themed dress code. Certainly the Accident and Emergency Department became a colourful place with variously injured patients in flamboyant dress and in a generally “exuberant” mood. In all, eight patients were admitted (one patient for every 17 min of the disco).’

Swani, M. S. (1974). ‘Disco Deafness.’ British Medical Journal 4 (5943): 532.

Peck, R. J., Karen Ng, and Arthur Li (1988). ‘The Dyspeptic Disco Dancer.’ British Journal of Radiology 61 (725): 417–18.

Dewitt, L. D., and H. S. Greenberg (1981). ‘Roller Disco Neuropathy.’ Journal of the American Medical Association 246 (8): 836.

Redmond, J., A. Thompson, and M. Hutchinson (1983). ‘Acute Central Cervical Cord Injury Due to Disco Dancing.’ British Medical Journal 286 (6379): 1704.

Dörner, A., H. J. Kahl, and K. H. Jungbluth (1985). ‘The Roller Discotheque: A Quickstep to the Hospital? An Analysis of 196 Accidents.’ Unfallchirurgie 11 (4): 181–86.

Bar-Sela, S. M., and J. Moisseiev (2007). ‘Valsalva Retinopathy Associated with Vigorous Dancing in a Discotheque.’ Ophthalmic Surgery, Lasers & Imaging 38 (1): 69–71.

Cookson, Susan Temporado, José L. Corrales, José O. Lotero, Mabel Regueira, Norma Binsztein, Michael W. Reeves, Gloria Ajello, and William R. Jarvis (1998). ‘Disco Fever: Epidemic Meningococcal Disease in Northeastern Argentina Associated With Disco Patronage.’ Journal of Infectious Diseases 178 (1): 266–69.

Pappalardo, Margaret Doyle (1980). ‘The Effects of Discotheque Dancing on Selected Physiological and Psychological Parameters of College Students.’ PhD thesis, Boston University School of Education.

Taylor, Bruce H. (1980). ‘Shake, Slow, and Selection: An Aspect of the Tradition Process Reflected by Discotheque Dances in Bergen, Norway.’ Ethnomusicology 24 (1): 75–84.

Highcock, A .J., K. Rourke, and D. Brown (2008). ‘The University Rollerdisco: An Unusual Cause of a Major Incident.’ Injury Extra 39 (12): 386–88.

In Brief

‘Punk Rocker’s Lung: Pulmonary Fibrosis in a Drug Snorting Fire-Eater’

by D. R. Buchanan, D. Lamb, and A. Seaton (published in the British Medical Journal, 1981)

The Toothless Rule of Louis XIV

French teeth are something of a specialty for the president of Great Britain’s Royal Historical Society. Colin Jones, who is also a history professor at Queen Mary, University of London, has written two memorable monographs on the subject.

Evidence of a huge Parisian tooth-yanker. ‘A French Dentist Shewing a Specimen of His Artificial Teeth and False Palates’ by Thomas Rowlandson (1811). Wellcome Library, London

Jones’s study, called ‘Pulling Teeth in Eighteenth-Century Paris’, centres on a literally huge Parisian tooth-yanker called Le Grand Thomas. Jones explains: ‘For nearly half a century, from the 1710s to the 1750s, Thomas was a standard fixture, a living legend, plying his dental wares on the Pont-Neuf in Paris ... If the tooth he was attacking repulsed his assaults he would, it was said, make the individual kneel down, then, with the strength of a bull, lift him three times in the air with his hand clenched on the recalcitrant tooth.’ Jones suggests that a well-informed toothache sufferer, surveying the major healthcare options, might reasonably opt for Le Grand Thomas or one of his many self-taught peers.

Surgeons, the people most likely to do a good job, were enjoying a rise in prestige and fees. They would commonly decline the pedestrian, relatively low-paying task of tooth-pulling. Doctors and apothecaries ‘were both still primarily hands-off practitioners’ whose services might be expensive and whose array of remedies still included things like ‘the ingestion of flayed, crushed and cooked mouse’.

Given these alternatives, Jones writes, ‘it is not difficult to imagine that the limited dental skills of the smithy or the therapeutic value of casseroled mouse must have opened up a niche for a more helpful and more imaginative approach. This niche appears to have been filled by men of the stripe of Le Grand Thomas’.

Jones also wrote a study called ‘The King’s Two Teeth’. The title refers to the two choppers present at birth, in 1638, in the mouth of Louis XIV, the man who would later be called Louis the Great and Louis the Sun King. ‘To contemporaries’, writes Jones, ‘this prodigious, gluttonous, voracious pair of teeth seemed to presage the wonders which the hungrily devouring prince would in the fullness of time effect on the map of Europe.’

Jones mentions a tradition of French royal portrait painting: kingly teeth, even when existing and beautiful, were always hidden behind closed lips.

But traditions would change.

A much-celebrated portrait done in 1701, of a sixty-three-year-old Louis ‘at the height of his powers’ shows the king with impressively youthful legs and posture. Even with this blatant inaccuracy, Jones says, ‘one feature stands out – and shocks – for its stark naturalism: hollow cheeks and wrinkled mouth reveal a ruler with not a tooth in his head’.

Together with the development of better dental medicine, he concludes, ‘the replacement of the tooth puller by the dentist and the emergence on the marketplace of a powerful demand for a different kind of mouth all in their different ways highlighted a silent revolution of the teeth and the smile which bade to put paid to the Old Régime of Teeth’.

Jones, Colin (2000). ‘Pulling Teeth in Eighteenth-Century Paris.’ Past and Present 166 (1): 100–45.

–– (2008). ‘The King’s Two Teeth.’ History Workshop Journal 65: 79–95.

Mummies’ Recipe for Good Health

Nowadays, powdered mummy may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but for many years it was just what the doctor ordered. That’s one of the takeaway messages of Richard Sugg’s study ‘“Good Physic but Bad Food”: Early Modern Attitudes to Medicinal Cannibalism and its Suppliers’. Sugg, a research fellow in literature and medicine at Durham University, in the UK, begins with an observation: ‘The subject of medicinal cannibalism in mainstream western medicine has received surprisingly little historical attention.’

Sugg tells us that mummy, generally in powdered form, ‘having originally been a natural mixture of pitch and asphalt, came in the twelfth century to be associated with preserved Egyptian corpses’. It then ‘emerged as a mainstream western medicine’ and remained a standard-issue drug until ‘opinion began to turn against it in the eighteenth century’.

Physicians prescribed powdered mummy for diverse ailments. An English pharmacopeia published in 1721 specifies two ounces of mummy as the proper amount to make a ‘plaster against ruptures’. Ambroise Paré, royal surgeon to sixteenth-century French kings, proclaimed mummy to be ‘the very first and last medicine of almost all our practitioners’ against bruising.

Dr Paré harboured doubts about the drug’s efficacy, lamenting that ‘wee are ... compelled both foolishly and cruelly to devoure the mangled and putride particles of the carcasses of the basest people of Egypt, or such as are hanged’. But Paré was an unusually driven doubting Thomas – he lamented having ‘tried mummy “an hundred times” without success’.

Sugg’s study explains that ‘mummy was an important commodity. It is often seen in long lists of merchants’ wares and prices.’ The marketplace attracted counterfeiters. Sugg supplies an anecdote: ‘Tellingly, when Samuel Pepys saw a mummy it was in a merchant’s warehouse; while “the abuses of mummy dealers in selling inferior wares” were especially widespread and notorious by the end of the seventeenth century.’

The best suppliers maintained high standards. The presumably admirable recipe used by seventeenth-century German pharmacologist Johann Schroeder included ‘the cadaver of a reddish man (because in such a man the blood is believed lighter and so the flesh is better), whole, fresh without blemish, of around twenty-four years of age, dead of a violent death (not of illness), exposed to the moon’s rays for one day and night, but with a clear sky. Cut the muscular flesh of this man and sprinkle it with powder of myrrh and at least a little bit of aloe, then soak it.’

Sugg, Richard (2006). ‘“Good Physic but Bad Food”: Early Modern Attitudes to Medicinal Cannibalism and its Suppliers.’ Social History of Medicine 19 (2): 225–40.

To Be Michael Jackson, After a Refashioning

In 1997, a twenty-four-year-old Belgian man requested that his head be reconstructed to make him resemble the singer Michael Jackson. Three plastic surgeons granted his wish. Their report about it, published in the journal Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthetique, is a lovely sight to behold. The loveliness is partly in the detailed technical description, monochromatically in the set of before-and-after X-rays of the facial bones, and memorably in the medically stylish photographs that show the young man before and after his course of treatment.

The doctors, Maurice Mommaerts and Johan Abeloos, of the Hôpital Général Saint-Jean in Bruges, Belgium, and H. Gropp, of the Diakoniehospital in Bremen, Germany, described the patient’s challenge to them: ‘His quest was to obtain the facial features of Michael Jackson, his idol that he imitated professionally.’ This was an unusual demand. The doctors explain that ‘normally, patients strive for an ideal, beautiful, normal contour [of the facial bones]. We were confronted with a patient who requested a three-dimensional overcorrection.’

Their patient was no ordinary young man. He impressed the doctors with the firmness of his desire, but also with his detailed knowledge of his own craniofacial anatomy (especially his gonial angles and malar prominence).

This task, the doctors decided, after only minimal hesitation, was something they could do. ‘After thorough discussion and psychiatric analysis, we agreed to morph him in a way that all changes could be undone and that the tissues were not at risk for considerable permanent damage.’

The case was both easy and hard. The surgeons immediately saw simple ways to rearrange the young man’s chin and also his cheekbone arches. But how to achieve the desired posterior-mandibular augmentation? That was the puzzler; solving it would be a medical first.

The doctors rose to the posterior-mandibular augmentation challenge. They conquered it and, in so doing, made history. Two rounds of surgery did the trick. Full details are in their report. For non-specialists, the important feature may be the simple and comforting piece of knowledge: Yes, we now know, it is possible to surgically morph a long-jawed Belgian white youth so that he looks just like Michael Jackson.

Yet, a prominent institution that houses that particular type of individual suddenly has, at least potentially, a big problem. Hordes of people want to see him, touch him, admire him, maybe even serve legal papers on him. I found no reports of that happening with this Belgian doppelganger. I suspect that is because the surgeons kept up with the medical literature, and had learned from a 1996 report in the journal Hospital Security and Safety Management. That instructional article, written in the wake of Mr Jackson’s unfortunate and dramatic collapse on stage in New York City, is called: ‘Michael Jackson at Beth Israel: Handling Press, Fans, Gawking Employees’.

Mommaerts, M. Y., J. S. Abeloos, and H. Gropp (2001). ‘Mandibular Angle Augmentation with the Use of Distraction and Homologous Lyophilized Cartilage in a Case of Morphing to Michael Jackson Surgery.’ Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthetique 46 (4): 336–40.

N. A. (1996). ‘Michael Jackson at Beth Israel: Handling Press, Fans, Gawking Employees.’ Hospital Security and Safety Management 16 (12): 10–11.

Pursuing a Wretched Itch

Can capsaicin – the chemical that causes most of the burning sensation when you chomp on a chilli pepper – relieve itching at the nether end of the digestive tract? A team of Israeli scientists tried to find out.

They tackled a maddening medical condition called ‘idiopathic intractable pruritus ani’. Most people, including most doctors when they are talking informally to each other, use the less-formal name: ‘persistent butt itch’. It is one of a wide class of medical conditions that sound humorous until you experience them yourself. And then they still sound funny, which perhaps adds to the discomfort.

Dr Eran Goldin and a large team of colleagues at Hadassah University Hospital, in Jerusalem, collected forty-four patients who suffered from chronic butt itch. Each had endured at least three months of suffering. None had responded to the traditional treatments – gentle washing and drying of the affected area, and avoidance of certain foods that are famous for causing chronic butt itch.

Coffee, tea, cola, beer, chocolate, and tomatoes are thought to be the six biggest causes of the problem, identified as such in a 1997 report by William G. Friend of the University of Washington. Friend believed that coffee is the main culprit, responsible for about eighty percent of all cases of intractable butt itch. Drink less coffee and you’ll be able to sit still, if you are one of the luckier butt itch sufferers. The forty-four Israeli itch victims, though, did not have that sort of luck. Theirs was an itch of unknown origin, a head-scratching puzzle for any doctor who tried to treat them.

Goldin and his team solved this puzzle for thirty-one of their forty-four patients by applying the capsaicin topically. Four patients did feel what Goldin called ‘a very mild perianal burning lasting 10–15 minutes’ after the treatment, but apparently this was for them a small price to pay.

Some months later, the doctors checked up on eighteen of the patients. All said they were still feeling pretty good, so long as they gave themselves an anal dose of capsaicin every day or two. The Goldin report concluded that ‘capsaicin is a new, safe, and highly effective treatment for severe intractable idiopathic pruritus ani’.

While new for treating this very specific ailment, capsaicin was already, as the doctors themselves point out, generally ‘known to be effective and safe in the treatment of pain and itching’. Capsaicin was also, of course, known to have rather ferocious effects when placed into the front end of a person’s digestive system.

A 2002 experiment by doctors at L. Nair Hospital in Mumbai, India, explored both sides of the action. The research team fed ten grams of red chilli powder (in other words, a heaping dose of capsaicin) to twenty-one men who have well-tempered bowels. The doctors report that this ‘increases the rectal threshold for pain’. You will forgive me, I hope, for not describing how they performed that measurement.

Lysy, J., M. Sistiery-Ittah, Y. Israelit, A. Shmueli, N. Strauss-Liviatan, V. Mindrul, D. Keret, and E. Goldin (2003). ‘Topical Capsaicin – A Novel and Effective Treatment for Idiopathic Intractable Pruritus Ani: A Randomised, Placebo Controlled, Crossover Study.’ Gut 52: 1323–26.

Friend, William G. (1977). ‘The Cause and Treatment of Idiopathic Pruritus Ani.’ Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 20 (1): 40–42.

Agarwal, M. K., S. J. Bhatia, S. A. Desai, U. Bhure, and S. Melgiri (2002). ‘Effect of Red Chillies on Small Bowel and Colonic Transit and Rectal Sensitivity in Men with Irritable Bowel Syndrome.’ Indian Journal of Gastroenterology 21 (5): 179–82.

The Fingernails of Dr Bean

Many people, especially academics and taxi drivers, take pride in having arcane knowledge at their fingertips. Dr William B. Bean bested them all. Bean’s arcane knowledge was not only at his fingertips; it was about them. Bean spent much of his adult life monitoring the growth of his fingernails. He trimmed his nails neither to be fashionable nor to add to his press clippings. He did it for science.

William B. Bean (born 1909, died 1989) conducted what is known as a longitudinal self-study of fingernail growth. It is one of the few such studies known, and perhaps the lengthiest. Bean taught for many years at the University of Iowa College of Medicine and later at the University of Texas medical branch at Galveston, Texas. The cuticle research was published, in pieces and at intervals, in the Archives of Internal Medicine, of which Bean happened to be editor.

In 1968, the first of the Bean nail papers arrived in print. Called ‘Nail Growth: Twenty-Five Years’ Observation’, its timing was unfortunate for Bean, in that the world was distracted by riots, assassinations, the Vietnam war, and the nail-biting American presidential election in which Richard Nixon rose to power. The year 1974 saw the publication of Bean’s extended observations. His paper ‘Nail Growth: 30 Years of Observation’ was published just a few weeks after President Nixon’s attention-grabbing resignation from the American presidency. Again, Bean received scant acclaim.

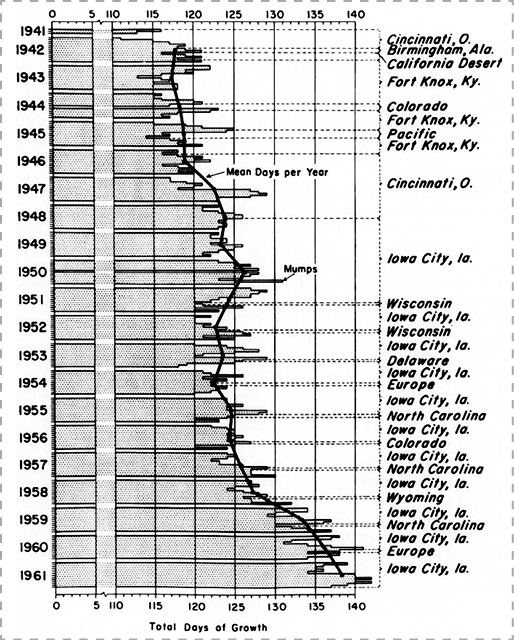

Dr Bean’s twenty-year nail chart from ‘Nail Growth and Unusual Fingernails’

Two years later, perhaps growing a little impatient, Bean drummed his metaphorical fingertips on a different tabletop, publishing a cuticle-centric essay not in his own journal, but in the International Journal of Dermatology. Under the headline ‘Some Notes of an Aging Nail Watcher’, he explained: ‘Growth of deciduous tissues gives us a natural kymograph to record secular trends and in some instances makes the mark on the moving record. For the observant clinician, knowledge of the rate of nail growth may permit an occasional spectacular diagnosis, although much more often it merely adds a small bit to our understanding of simple but basic biological principles in health and disease.’ This seems to have produced a gratifying response.

Thereafter, Bean returned to his original, deliberate publication schedule. In 1980 he produced ‘Nail Growth: Thirty-Five Years of Observation’. It is as complete a story as the world has ever seen about the growth of one physician’s fingernails. Here is his summary: ‘A 35-year observation of the growth of my nails indicates the slowing of growth with increasing age. The average daily growth of the left thumbnail, for instance, has varied from 0.123 millimeters a day during the first part of the study when I was 32 years of age to 0.095 millimeters a day at the age of 67.’

Bean, William B. (1962). ‘A Discourse on Nail Growth and Unusual Fingernails.’ Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association 74: 152–67.

–– (1968). ‘Nail Growth: Twenty-Five Years’ Observation.’ Archives of Internal Medicine 122 (4): 359–61.

–– (1974). ‘Nail Growth: 30 Years of Observation.’ Archives of Internal Medicine 134 (3): 497–502.

–– (1976). ‘Some Notes of an Aging Nail Watcher.’ International Journal of Dermatology 15 (3): 225–30.

–– (1980). ‘Nail Growth. Thirty-Five Years of Observation.’ Archives of Internal Medicine 140 (1): 73–76.

New Pet Theory

Some Australian researchers have put forward a new pet theory about older people and their beloved pets, which many have claimed, including the Medical Journal of Australia, are ‘good for health’ – the health of humans. This new theory is blunt in overturning this assumption.

Susan Kurrle and Robert Day, of the Hornsby Ku-ring-gai Health Service in Sydney, Australia, and Ian Cameron, of the University of Sydney, looked at cases of pet-related falls that brought patients seventy-five years and older to one particular hospital during a six-month period. They defined pets as ‘an animal which is kept as a companion and is treated with affection’. This included animals such as goats and donkeys, as well as dogs, cats, and birds. They narrowed their definition of the injured to fall victims who sustained a traumatic bone fracture. Their analysis excluded injuries that ‘occurred as a result of older people being startled by mice, cockroaches or spiders, as these animals were not considered pets for the purpose of this study.’

The circumstances of each case, as presented in the report, are plaintively stark. Here are a few, each quite typical:

- Taking Jack Russell terrier for walk using retractable leash. Dog ran round and round patient’s legs and pulled him over.

- Climbing stile over fence to feed mohair goats, slipped and fell to ground.

- Feeding donkey from bucket. Donkey nudged patient, pushing her over backwards.

- Slipped on puddle of urine from new Labrador pup. Fell against wooden arm of armchair.

- Fell forwards while trying to prevent young puppy from diving into fish tank.

- Fell sideways in garden while trying to stop cat catching a blue tongue lizard.

- Tripped over black cat in darkened hallway.

- Fall while attempting to move quickly out back door as cat carried live snake in through side door.

‘There were no deaths recorded as a result of the fall-related fractures’, Kurrle et al. tell us, ‘but one of the animals involved (a cat) died when its owner fell and landed on it.’

Kurrle, Susan E., Robert Day, and Ian D. Cameron (2004). ‘The Perils of Pet Ownership: A New Fall-Injury Risk Factor.’ Medical Journal of Australia 181: 682–83.

Addressing the Karaoke Pandemic, Vocally

A scientific experiment may look like torture, and sound like torture, yet still be free of legal ramifications. At the University of Hong Kong, Edwin M.-L. Yiu and Rainy M. M. Chan did an experiment that smacks of torture for the participants, the experimenters, and anyone within earshot. Their published report has a title that evokes wretchedness: ‘Effect of Hydration and Vocal Rest on the Vocal Fatigue in Amateur Karaoke Singers’.

The experiment brought several hours of continuous, mounting, painful discomfort to a group of human volunteers. Yet the scientists’ aim was noble. They write that ‘karaoke singing is a very popular entertainment among young people in Asia ... It is not uncommon to find participants singing continuously for four to five hours each time. As most of the karaoke singers have no formal training in singing, these amateur singers are more vulnerable to developing voice problems under these intensive singing activities.’

This modestly understates the problem. Many thousands of young persons sing karaoke. Multiply that by the duration of singing – four or five hours. Now multiply that by the average number of times per week each person sings karaoke. Then multiply by fifty-two weeks. The resultant sum represents a groaning annual burden of painful singing, on a continental scale. And that’s just Asia. Karaoke is pandemic on at least six continents.

The experimental subjects were a carefully chosen bunch, all in their early twenties, in good health, and in the habit of singing karaoke at least twice a week. They had no formal voice or singing training, no history of voice problems, and no chronic psychiatric problems worth mentioning.

Yiu and Chan performed this experiment at the university’s voice research laboratory. Each person ‘was asked to sing in a quiet room with karaoke facility, which provided music video on a television and background music with echo effects ... The participants were required to sing continuously until they reported feeling fatigue with their voices and could not sing anymore.’

Ten of them got to rest for a minute after each song, and drink some water. The other ten received neither hydration nor rest; they bopped till they dropped, so to speak.

The hydrated singers sang longer, if not better, than those denied liquid. The former averaged more than one hundred minutes of warbling, the latter about eighty-five. (The four to five hours they claim to sing while at karaoke clubs presumably includes lots of down time.)

Yiu and Chan did find a surprise. They had expected the wet singers to sing better than the dry. This expectation was largely unmet. Assessments by trained ears and eyes (the latter involving phonetograms – electroacoustically produced graphs of pitch and loudness) showed that, warble for warble, vocal quality levels were roughly the same for both groups.

Unskilled singers, one might infer from this, seldom exceed mediocrity yet seldom fail to achieve it. Occasional water and rest can help them prolong their remarkable record of achievement.

Yiu, Edwin M.-L., and Rainy M. M. Chan (2003). ‘Effect of Hydration and Vocal Rest on the Vocal Fatigue in Amateur Karaoke Singers.’ Journal of Voice 17 (2): 216–27.

Hives on the Pitch

‘This is the first reported case of an urticarial rash apparently caused by the frustration of watching England play football.’

With these words, written in 1987, a London general practitioner trainee named P. Merry alerted readers of the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine to a little-suspected risk of rooting for a World Cup football team. Rooting can cause emotional upset, which can cause urticaria. Urticaria is also known as ‘hives’.

Here’s what happened to the patient, who followed the game on TV: ‘When Portugal scored the only goal of the match to win 1-0, he became extremely upset, and developed the rash of urticaria affecting his trunk and limbs. This persisted for 36 hours and then settled.’ Four days later, the man watched England vs. Morocco. ‘When a member of the English team was sent off, he became agitated and subsequently developed the same rash of urticaria on his trunk and limbs.’

Then, in 2006, thirty-four-year-old Paul Hucker, of Ipswich, Suffolk, UK, made headlines because he bought an insurance policy against possible trauma brought on by an England defeat in the World Cup. Many chuckled at the news. A wander through the medical literature suggests the chucklers should temper their amusement.

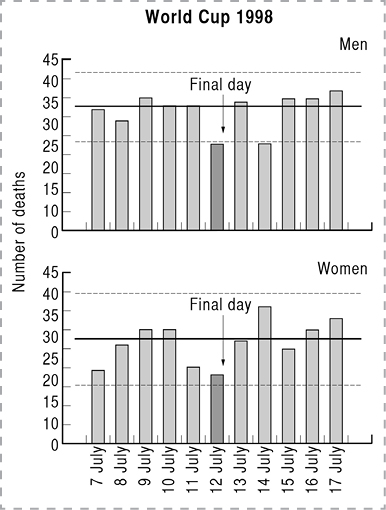

Five researchers at the University of Bristol published a warning in 2002, in the BMJ, that ‘myocardial infarction can be triggered by emotional upset, such as watching your football team lose an important match’. Their main evidence: British hospital statistics accumulated at the time of the 1998 World Cup. ‘Risk of admission for acute myocardial infarction’, the doctors point out, ‘increased by 25% on 30 June 1998 [the day England lost to Argentina in a penalty shoot-out] and the following two days.’

Number of deaths from myocardial infarction, French men vs. French women. France played Brazil in the final of the World Cup on 12 July 1998.

Four researchers in Lausanne, Switzerland, say a similar thing happened during the 2002 World Cup. They lay out their stats in a 2006 issue of the International Journal of Cardiology. The number of sudden cardiac deaths was sixty-three percent higher during the World Cup than during the equivalent period a year earlier, when there was no World Cup competition. The doctors try to analyse it: ‘We explain this by an increase in mental stress and anger and possible unhealthy behaviour (increased alcohol and tobacco consumption, decreased medical compliance) of football supporters. The lethal effect of mental stress and anger has been attributed to its activation of the sympathetic nervous system leading to hypertension, impaired myocardial perfusion in the setting of atherosclerotic disease and a high degree of cardiac electrical instability precipitating malignant arrhythmias.’

Fandom carries danger, yes, but there’s a special payoff for those whose side does capture the ultimate glory. Or so implies a study that appeared in 2003 in the journal Heart. Written by two French doctors, the title proclaims: ‘Lower Myocardial Infarction Mortality in French Men the Day France Won the 1998 World Cup of Football’.

Merry, P. (1987). ‘World Cup Urticaria.’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 80 (12): 779.

Carroll, D., S. Ebrahim, K. Tilling, J. Macleod, and G. D. Smith (2002). ‘Admissions for Myocardial Infarction and World Cup Football: Database Survey.’ BMJ 325: 1439–42.

Katz, Eugène, Jacques-Thierry Metzger, Alfio Marazzi, and Lukas Kappenberger (2006). ‘Increase of Sudden Cardiac Deaths in Switzerland during the 2002 FIFA World Cup.’ International Journal of Cardiology 107 (1): 132–33.

Berthier, F., and F. Boulay (2003). ‘Lower Myocardial Infarction Mortality in French Men the Day France Won the 1998 World Cup of Football.’ Heart 89 (3): pp. 555–56.

Object RCSHC/P 192

The rectum of the Bishop of Durham sits on display in London, awaiting your examination. No longer attached to the bishop, it rests alone inside a glass jar in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. The museum calls it by the formal name: Object RCSHC/P 192.

Visitors can casually admire the object’s beauty. Scholars and poets can find unexpected delights in studying and writing up the bishop’s rectum. This apparently humble body part can boast a historic connection to John Hunter, the surgeon whose collection of medical memorabilia eventually grew to become the Hunterian Museum.

The museum officially gives a simple description of Object RCSHC/P 192: ‘A rectum showing the effects of both haemorrhoids and bowel cancer. The patient in this case was Thomas Thurlow (1737–91), the Bishop of Durham. Thurlow had suffered for some time from a bowel complaint, which he initially thought was the result of piles. He consulted John Hunter after a number of other physicians and surgeons had failed to provide him with a satisfactory diagnosis. Hunter successfully identified the tumour through rectal examination but recognised that it was incurable. Thurlow died ten months later.’

Hunter wrote extensive notes about how he entered the case, examined the rectum (which at the time was, of course, still an integral part of the bishop), and immediately recognized, by feel, that it had an incurable tumour.

The notes also tell how events played out. The bishop, disbelieving Dr Hunter’s diagnosis, then tried to cure himself with a nostrum called Ward’s White Drops. He was choosing to rely on past experience with a lesser ailment, rather than accept Hunter’s professional assessment. Hunter notes that ‘his Lordship had, about ten years ago, the piles, for which he took Ward’s Paste, and was cured’.

The White Drops did not cure the bishop’s cancer. Instead, his discomfort increased. Hunter writes that the family then called in ‘Taylor the cattle-doctor to attend him, and I was asked to examine this doctor, to see whether it was likely he should do mischief or not’. Hunter concluded that Taylor would do no mischief. Taylor deferred happily to the renowned physician’s opinions and, with his approval, gave the bishop opium and ointments, to ease the distress.

Ten months later, the bishop breathed his last. John Hunter performed an autopsy, savouring the opportunity to write a detailed technical assessment of the tumour and of its role in killing a patient who doubted the doctor’s diagnosis.

The copious details are a bit grisly for a general audience. Hunter’s notes were intended for himself or for others of his profession, should he or they encounter a similar rectum or a similar patient. Now, more than two hundred years later, the story, and a good view of the rectum, are available to anyone who seeks enlightenment.

Steve Farrar noticed the bishop’s rectum and brought me to visit it. That resulted in tea with Simon Chaplin, the museum’s director, who has a special fondness for and knowledge of historic body parts. I am and will eternally be grateful to both men for their insights into the remaining bit of bishop.

May We Recommend

‘No-Scalpel Vasectomy at the King’s Birthday Vasectomy Festival’

by Apichart Nirapathpongporn, Douglas H. Huber, and John N. Krieger (published in the Lancet, 1990)

101 Uses for the Sacred Foreskin

A study called ‘The Circumcision of Jesus Christ’ pioneers a new flavour of interdisciplinary research: urology at last joins forces with theology. Published in the Journal of Urology, the study focuses on what happened to Jesus’s foreskin during and especially after biblical times.

Lead author Johan J. Mattelaer brings a broad perspective to this narrow topic. A past chairman of the History Office of the European Association of Urology in Kortrijk, Belgium, and professor emeritus of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Mattelaer earlier wrote a book called The Phallus in Art and Culture. And shortly before taking on the sacred foreskin project, he teamed up with Austrian-Canadian neuropsychologist Wolfgang Jilek to write a study called ‘Koro: The Psychological Disappearance of the Penis’. For the Jesus circumcision study, Mattelaer and colleagues Robert A. Schipper and Sakti Das delved into two thousand years’ worth of religio-phallocentric writings, paintings, sculpture, music, and theological disputes.

There is art aplenty, they explain, but ‘it seems paradoxical that uncircumcised Christian artists created so many images relating to the circumcision of Jesus in painting and sculpture. In Belgium alone there are no less than fifty-four listed works in churches, museums, and public buildings relating to Christ’s circumcision, including paintings, grisaille, frescos, statues, altarpieces, stained glass windows and keystones.’ Greek and Russian Orthodox church icons, they report, commonly contain circumcision images.

Musicians produced only a few works. The most prominent is ‘Missa Circumcisionis Domini Nostri Jesu Christi’ (‘Mass for the Circumcision of Our Lord Jesus Christ’), composed by Jan Dismas Zelenka of Dresden in 1728.

Churches, museums, crusaders, and kings sought to have and hold the actual foreskin. The study notes that ‘the Dominican scholar A. V. Müller, writing in 1907, could list no fewer than 13 separate locations, all of which claimed to possess the sacred foreskin as their holiest relic. We have been able to extend this list to 21 churches and abbeys, which at one time or another are reputed to have held Christ’s foreskin.’

The study also reports that King Henry V stole the genuine article – the one so identified by Pope Clement VII – from the French in 1422, and that ‘the monks of Chartres were only able to recover it with great difficulty’.

Several theologians devoted their lives to the foreskin. Two remain emblematic. St Catherine of Siena (1347–80), to symbolize her marriage with Christ, ‘was reputed to wear the foreskin of Jesus as a ring on her finger’. A generation or so earlier, the Austrian nun Agnes Blannbekin ‘led a life devoted to the foreskin of Jesus’. The study says: ‘She was obsessed by the loss of blood and the pain which the redeemer had suffered during his circumcision. On one occasion when she was moved to tears by the thought of this suffering, she suddenly felt the foreskin on her tongue.’

The study reproduces a 1523 painting of St Catherine and her ring, but, perhaps deferring to current tastes, supplies no visual image of Agnes Blannbekin.

Mattelaer, Johan J. (2003). The Phallus in Art and Culture. Arnhem, The Netherlands: European Association of Urology History Office.

––, Robert A. Schipper, and Sakti Das (2007). ‘The Circumcision of Jesus Christ.’ Journal of Urology 178: 31–34.

––, and Wolfgang Jilek (2007). ‘Koro: The Psychological Disappearance of the Penis.’ Journal of Sexual Medicine 4 (5): 1509–15.

Death by Aspiration

One’s aspirations can kill – if Dr Sakae Inouye, of Otsuma Women’s University in Tokyo, is correct – and Chinese aspirations are particularly deadly.

Inouye devised a simple theory about a vexing public health problem. His theory is this: the English language, when spoken by someone who normally speaks the Chinese language, can be lethal.

Inouye drove his train of logic through the pages of the Lancet: ‘Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is transmitted via droplets spread by infected individuals. Droplets are generated when patients cough and, to a lesser extent, when they talk during the early stages of disease. I believe that the efficiency of transmission of SARS by talking might be affected by the language spoken.’

Here are the details of Inouye’s reasoning. They are subtle. They are breathtaking. They should perhaps be read silently.

- The disease called SARS seems to have originated in China.

- China has had millions of visitors from the US, and even more visitors from Japan.

- Some American visitors (about seventy out of 2.3 million) got the disease – but no Japanese visitors did.

- There must be a reason for that.

- The reason must be: language. In both Chinese and English, many sounds have a strong accompanying exhalation of breath – but Japanese has no such sounds.

- The final step in the chain brings these pieces together. It is frightful. Dr Inouye writes that: ‘A Chinese attendant in a souvenir shop probably speaks to American tourists in English, and to Japanese tourists in Japanese. If the shop assistant is in the early stages of SARS and has no cough, I believe American tourists would, hence, be exposed to the infectious droplets to a greater extent than would Japanese tourists.’

Inouye does not specify a particular dialect of Chinese, so at the moment all are suspect.

If one’s spoken language is dangerous, can it be altered? Nearly a century ago, future Nobel Prize winner George Bernard Shaw raised this very question. In the printed preface to his play Pygmalion, about a professor who painstakingly alters the speech patterns of a young woman, Shaw wrote: ‘The change wrought by Professor Higgins in the flower girl is neither impossible nor uncommon ... But the thing has to be done scientifically, or the last state of the aspirant may be worse than the first.’

Inouye, Sakae (2003). ‘SARS Transmission: Language and Droplet Production.’ Lancet 362 (9378): 170.

In Brief

‘Attempted Suicide or Hitting the Nail on the Head: Case Report’

by A. S. Spears (published in the Journal of the Florida Medical Association, 1994)

The authors at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Florida, report: ‘A case is reported of attempted suicide by hammering nails through the skull into the brain. This unique attempt at self-destruction was unsuccessful and the treatment, initially by an untrained first-aider and then by a neurosurgeon, was surprisingly simple.’