Aldon Morris

By the turn of the twentieth century, the Industrial Revolution had transformed the modern world. Cultural producers from nations around the globe assembled at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris from April to November. Their purpose was to display artifacts signifying great national achievements and provide evidence suggesting even greater accomplishments in the new century. The fair presented a global stage for nations to strut their sense of national pride.

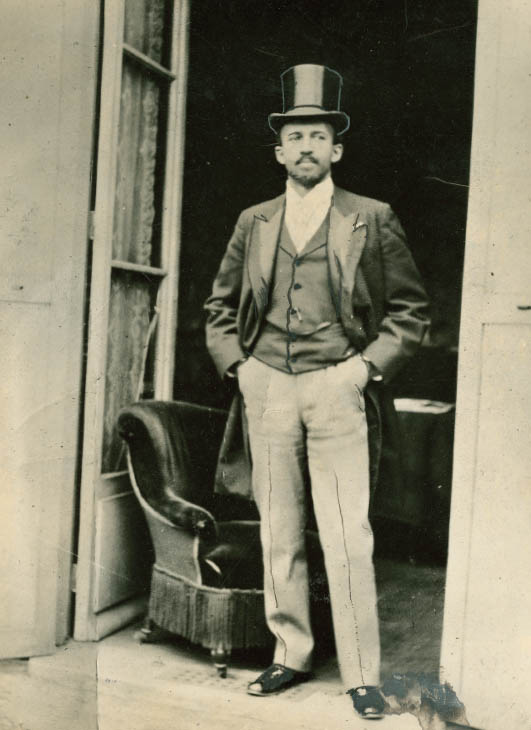

At the turn of the century, portrayals of black people as subhuman, incapable of attaining great material and cultural achievements, were commonplace throughout the western world. Yet, a different view emerged from the American Negro Exhibit at the Exposition. Here, African Americans were displayed in a series of photographs and artifacts as a proud people, dressed in splendor, as accomplished scholars and intellectuals studying the world with as much competence as one would imagine from students of Plato, Copernicus, Alexander Crummell, and Frederick Douglass. Indeed, African Americans were depicted as students, lawyers, doctors, major inventors, purchasers of property, and warriors against illiteracy, making major contributions on the world stage in the new century. Organizers of the exhibit bestowed nationhood on the recently freed slaves, referring to them as a small “nation within a nation.” This designation of a black nation conveyed the idea of a community with its own integrity, intricate culture, and complex social organization. This counterintuitive portrayal stunned throngs of world visitors who had never seen African Americans through this lens. The exhibit violated white thoughts about black people, especially Americans only three decades removed from slavery.

As the twentieth century approached, these ex-slaves found themselves exiled in their own land, where their unpaid slave labor had constructed one of the world’s great empires. Rather than benefitting from this bounty, freedmen and -women found themselves homeless, penniless, stripped of the vote, unable to seek education, and patrolled by whites. Indeed, a new racial order was forged. The Jim Crow regime made sure state laws required black subordination in the former Confederacy. In 1896 the United States Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson legalized Jim Crow rule across the land by declaring racial segregation constitutional so long as segregated facilities were equal. However, whites who never intended to establish equal facilities proceeded to support racial inequality under the guise of legality.

Lacking land, capital, and political rights, ex-slaves, now forced into exploitative relations with former masters, became sharecroppers with no power to benefit from these unequal relations, which predictably resulted in a system of debt peonage. Whites claimed that ex-slaves were the architects of their fate because of racial inferiority; this ideology maintained that blacks were the wretched of the earth because God and nature planned it that way. The disciplines of sociology, anthropology, history, and humanities during Du Bois’s time promoted scientific racism. In Du Bois’s view, “science” justified this regime of racial exploitation, which in essence was slavery by a new name.

Racial subordination resulted from material powerlessness of the ex-slaves, who had little access to capital and land. African Americans were exploited economically because, despite being forced to provide intensive labor, they depended on meager incomes begrudgingly paid by white elites. Their extreme poverty exacerbated political powerlessness, and their low levels of education provided ideological justification for their servitude.

Although systematically disenfranchised and dispossessed, African Americans mobilized their agency to rebel and pursue economic survival and self-respect. Yet this agency produced by ex-slaves went unacknowledged, denied and disavowed because it conflicted with claims that African Americans naturally belonged at the bottom of the Jim Crow order. Nevertheless, there always existed people acutely aware of their agency and the progress gained during their journey from slavery to freedom. Finally, at the American Negro Exhibit, a narrative of black agency was placed front and center.

There was nothing auspicious about the space assigned to the Negro Exhibit, nestled as it was in the right corner of a room in the Pavilion of Social Economy. To garner attention from this unenviable location, this exhibit would need to radiate its own sparkle and originality. It would require an imaginative resonance causing visitors to pause and marvel at the mysteries conveyed by the displays arrayed in the corner. This was no small task given the mission of the exhibit. The American Negro Exhibit successfully captivated thousands of curious visitors over the months it was on display. The exhibit garnered a number of prestigious prizes, including a gold medal awarded to Du Bois by Paris Exposition judges for “his role as ‘collaborator’ and ‘compiler’ of materials for the exhibit.”1

The power of the American Negro Exhibit derived from its sociological imagination.2 At the turn of the twentieth century, the discipline of sociology was in its infancy, and its scholars sought to make it a respected social science in America. As a pioneer of scientific sociology in the United States, Du Bois was one of the discipline’s leading lights. Du Bois’s sociological genius drove the creativity animating the exhibit. Regarding the exhibit’s sociological nature, Du Bois explained: “As one enters [the Pavilion of Social Economy], it is an exhibit which, more than most others in the building, is sociological in the larger sense of the term—that is, is an attempt to give, in as systematic and compact a form as possible, the history and present condition of a large group of human beings.”3

The exhibit’s sociological narrative was the result of meticulous planning, on the part of both Du Bois and Thomas Calloway. Calloway explained the goals of the exhibit, writing, “Thousands upon thousands will go [to the fair], and a well selected and prepared exhibit, representing the Negro’s development in his churches, his schools, his homes, his farms, his stores, his professions and pursuits in general will attract attention...and do a great and lasting good in convincing thinking people of the possibilities of the Negro.”4

The sociological content of Calloway’s vision was remarkable. He made clear the exhibit would explore crucial aspects of the black American journey, including African American history, intellectual achievements, and advances in education and community building. Calloway was keen on depicting black agency, arguing that the exhibit should demonstrate “what the Negro is doing for himself” through his own organizations. Calloway’s sociological imagination reached beyond a narrow focus on African Americans to include “a general sociological study of the racial conditions in the United States”5 that chronicled and interpreted the social conditions fueling racial inequality. Calloway meticulously examined the materials to be shown in the exhibit and presented them to faculty and students at Atlanta University in order to receive feedback before they were shipped to Paris. Another African American, Daniel Alexander Payne Murray, played a crucial role in shaping the exhibit. Assistant librarian at the Library of Congress, Murray was a learned man who was an author, intellectual, and expert on black writers and black print cultures, including newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets. Calloway turned to Murray to acquire for the exhibit hundreds of published works by black writers in order to demonstrate black intellectual capacity and achievements in writing.

Du Bois was among the first professors in the nation to train students in sociological theory and empirical methodologies. He involved his students in fieldwork wherein they collected and analyzed data on the black community and race relations. Because these students were taught to think sociologically and engage in data analysis, the most advanced of the group became valuable assistants who compiled charts and graphs. Du Bois’s current and former students at Atlanta University were also crucially involved in the development of the exhibit; they worked with him to produce the sociological charts and graphs, doing so on a short timetable. Nevertheless, without Du Bois’s direction, training, and sociological imagination, the exhibit would not have blossomed into the masterpiece it became.

At the time of the Exposition, Du Bois’s experience of living in a racist America prepared him to lead the effort to construct the Atlanta University exhibit. Unlike average members of the black community who grew up under brutal Jim Crow racism in the South, Du Bois began life in the eastern United States in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Racism there was subtle and genteel. As a youth, Du Bois did not witness the horrors of lynching and racial violence. Nevertheless, because racism was national in scope, Du Bois first experienced racial discrimination while attending elementary school in Massachusetts. With this first encounter, Du Bois pledged to outperform whites: “Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others, or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut from their world by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination time, or beat them at a footrace, or even beat their stringy heads.”6 Although he experienced discrimination as a child, it was not until he headed to Fisk, a black university in Nashville, Tennessee, that he was faced with extreme prejudice. Entering the land of Jim Crow, which bore striking resemblances to slavery, Du Bois witnessed a virulent, open, and violent racism. It would not take Du Bois long to engage in activism to counter naked racism.

Rather than accept the bombardment of scientific racism, Du Bois launched intellectual and political attacks against it: “When I entered college in 1885, I was supposed to learn there was a new reason for the degradation of the coloured people—that was because they had inferior brains to whites. This I immediately challenged. I knew by experience that my own brains and body were not inferior to the average of my white fellow students. Moreover, I grew suspicious when it became clear that treating Negroes as inferior, whether they were or not was profitable to the people who hired their labor. I early, therefore, started on a personal life crusade to prove Negro equality and to induce Negroes to demand it.”7 In the South, Du Bois had to obey Jim Crow laws and customs, which applied to all aspects of southern life. He had to ride in the rear of trains where accommodations were filthy and filled with tobacco smoke. He ate meals with blacks and relieved himself in segregated toilets. Despite being a highly educated scholar, the elevated status routinely conferred on similarly situated whites eluded Du Bois. He never adjusted to these racist insults; rather, they often caused him to become angry in five languages. In his crusade to overthrow racism, he developed expertise as a social scientist, historian, philosopher, journalist, novelist, and poet. Du Bois, as he did throughout his life, utilized these talents to develop his contribution to the American Negro Exhibit. Given the talents Du Bois employed to challenge racist views and discrimination, and his dogged persistence, he was able to make inroads on many fronts. In so doing, Du Bois secured his stature as a towering activist of the twentieth century.

Du Bois’s own achievements were jarringly inconsistent with the myth of black inferiority. By age twenty, he had earned a bachelor’s degree from Fisk University. Three years later, he earned both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Harvard. By twenty-five, Du Bois had completed two years of advanced graduate studies at the University of Berlin. At the age of twenty-seven, Du Bois reached a milestone by becoming the first African American to earn a PhD from Harvard. His dissertation, Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, became the inaugural volume of Harvard’s 1896 series of Historical Studies. Du Bois’s 1899 book, The Philadelphia Negro, was the first American sociological study of an urban community. At this time, social scientific studies tended to have a social philosophy orientation unsupported by empirical data. The use of charts and graphs was rare, especially those that were aesthetically pleasing to the eye and the intellect. The achievement of The Philadelphia Negro was that it was steeped in empirical data with charts and graphs, which enabled Du Bois to chronicle and analyze the experience of black Philadelphians at the turn of the twentieth century. Du Bois had become one of the most talented sociologists in the nation by the time the idea of a Negro exhibit in Paris took root. However, despite his talent and the innovative nature of his work, white social scientists largely ignored Du Bois’s scholarship.

Although subverting scientific racism was a formidable task, Du Bois proceeded undeterred. In keeping with his sociological training at Harvard and Berlin, Du Bois was an astute analyst of the casual forces inhering in social conditions. His expertise included historical, statistical, and comparative analyses, enabling him to unveil the vexing effects of social conditions. Du Bois eschewed ahistorical accounts because he believed that an understanding of people resulted only from examining them in their historical contexts. To understand black people, and their journey from slavery to freedom, required examination with the historical microscope. Du Bois railed against unscientific conclusions based on hearsay and sloppy measurements. His advanced statistical training enabled him to critique and deplore uncritical applications of statistics, especially in studies pertaining to people of African descent. Du Bois pioneered the nation’s most sophisticated quantitative research on race and the black population.

The exhibit enabled Du Bois to attack white racist beliefs on a grand stage unavailable in the academy, where white scholars were driven by numerous prejudiced beliefs about African Americans. For instance, by subscribing to the social Darwinist paradigm that theorized the survival of the fittest, white scholars maintained black inferiority would inevitably lead to the population’s extinction. The distinguished white statistician, Frederick Hoffman, declared in 1896, “A combination of these traits and tendencies must in the end cause the extinction of the race.”8 Constructing blacks as a unique race constituted another flaw in studies by white scholars. This belief stemmed from the assumption that people of African descent were not full-fledged members of the human family, which would make comparisons between blacks and whites spurious and unnecessary. Du Bois, who possessed encyclopedic knowledge of social conditions in numerous countries, especially those in Europe, made numerous comparisons between African Americans and Europeans to demonstrate that similarly situated populations acted amazingly similar given shared social conditions. In this sense, Du Bois demonstrated that social conditions trumped race in accounting for social inequality. His contributions to the American Negro Exhibit relied on historical, statistical, and comparative data to challenge the racial stereotypes that were pervasive throughout the academic establishment.

Du Bois was aware that while unmoving prose and dry presentations of charts and graphs might catch attention from specialists, this approach would not garner notice beyond narrow circles of academics. Such social science was useless to the liberation of oppressed peoples. Breaking from tradition, Du Bois was among the first great American public intellectuals whose reach extended beyond the academy to the masses. Du Bois was able to achieve this feat by using a variety of writing styles ranging from scientific prose to lyrical outpourings across a number of genres that deeply touched readers’ emotions. To make their contribution to the American Negro Exhibit captivating, Du Bois and his Atlanta team decided to produce modern graphs, charts, maps, photographs, and other items that appeared to sparkle. They constructed hand-drawn graphs, charts, and maps arrayed in lively, vibrant colors punctuated by artistically intersecting lines. Bar data contained blocks of contrasting colors documenting the black experience. However, the art did not distract from science; it served to reinforce the comprehensive scientific data chronicling the African American journey. Looking at the images, one is reminded of William Wordsworth’s muse: “Dull would he be of soul who could pass by / A sight so touching in its majesty.”9 Indeed an array of dry displays at the exhibit would have been ineffective in subverting the social Darwinist paradigm.

Along with a general approach used to describe the black population nationally, Du Bois employed the case method for his work in the Georgia study. The case method relies on the in-depth study of a single case to reveal details and nuances of phenomena not attainable in a general study. The case method has become commonplace in sociology and anthropology because it allows the analyst to provide specificity to accompany macro-level analysis. Du Bois chose Georgia as a typical state to study African Americans in minute detail in order to add specificity to the national picture; Georgia was an ideal subject because it contained both urban and rural communities and was located close to Atlanta University, where Du Bois’s sociological laboratory was housed. Charts, graphs, statistics, and photographs from Georgia accompanied the data visualizations that depicted the United States more generally. Du Bois concluded, “It was a very good idea to supplement these very general figures with a minute social study in a typical Southern State.”10 Together, these methods, art, and analyses generate a powerful sociological narrative of the black experience that ranges in scope from local to international.

The essence of the exhibit’s narrative declared that African Americans had made amazing progress over just thirty-five years since Emancipation on most dimensions crucial to human well-being. This progress was remarkable given that black Americans had endured over two centuries of slavery, two decades of Jim Crow, and all the oppressive conditions associated with subjugation. The exhibit suggested that black progress since slavery compared most favorably with that of any human group faced with similar barriers.

Du Bois presented statistical data showing that the black population was increasing rather than decreasing, a direct refutation of social Darwinist theories. Comparative data in the exhibit demonstrated black fertility rates were as robust as that of many European countries. With a slap at the black extinction hypothesis, Du Bois declared, “A comparison of the age distribution with France [shows] the wonderful reproductive powers of the blacks.” Du Bois utilized the exhibit to refute the notion that black people were intellectually inferior, uninterested, and incapable of learning. He accomplished this by presenting graphs that showed the black illiteracy rate was rapidly declining and school enrollments were climbing. In graphs comparing black illiteracy rates with those of numerous European countries, Du Bois showed that black “illiteracy is less than that of Russia, and only equal to that of Hungary.”11 The Georgia study also contained hundreds of photographs depicting the physical and social heterogeneity of black people across the Southern state, as well as their dignity. This display of photographs made it difficult to reach any conclusion other than that the people reflected in these images embodied a beauty and grace of their own not describable by white standards of beauty.

The compilation of data displayed at the exhibit stressed one message: black progress since slavery. The colorful hand-drawn illustrations showed that ownership of black property and land was increasing. Black businesses were rising and so were the number of patents for black inventions. Such inventions overturned the white view that they “never knew a negro to invent anything but lies.”12 Black institutions of higher learning were moving firmly in the direction of educating the race. Other black institutions, including the church and mutual aid organizations, were increasingly fueling black agency. The collection was a masterpiece of sociology, celebrating black humanity on a world stage.

Du Bois was acutely aware that the packaging of the exhibit was as important as the data depicted. He understood what Duke Ellington expressed thirty years later: It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing. Du Bois and his students, working under a short deadline, analyzed volumes of data before converting them to succinct tables, graphs, and maps. Incredibly, they also mastered the art of drawing numerous illustrations with lively combinations of colors, creative lines, and eye-catching circles. Such visual sociology was rare in these early years of the discipline. In 1900, Du Bois was a pioneer in this form of sociology as he presented the black experience for the world to view at the Paris Exposition. It foreshadowed new possibilities of communicating sociological knowledge to the wider public. From the vantage point of the twenty-first century, the innovative sociology contained in the exhibit continues to stand the test of time.