Developing your thinking skills

Winston Churchill once said, ‘I am always willing to learn, but I do not like being taught.’ Actually, when you learn, you are being taught – by yourself. No doubt Socrates, if he was here, could teach you how to think, but he is not here. Nor is decision making and creative problem solving a school and university subject; there is no formal body of knowledge, supported by empirical research. And so, if you truly want to develop your thinking skills, your task is essentially one of self-development. In this chapter we shall look at some common-sense guidelines that you will need if you choose to go down that road.

What is an effective practical thinker?

Forming a clear picture of the kind of thinker you would like to be is the first step you need to take. A clear concept of what you might be one day can act as your magnet. Remember that point about formulating where you want to be and then working backwards?

You could do it in abstract terms, listing all the qualities, the knowledge, and the functions or skills you would like to acquire by such-and-such a date. I have to admit, though, that that does not work for me: it is a bit too academic. I suggest a more homely method, which any South Sea cannibal of olden times would have relished.

In Exercise 5 below I invite you to recall people whose thinking skills you have admired. They can be people you have known personally or have studied in some depth (by, say, reading more than one biography of them). In the right-hand column, write down as concisely and specifically as you can those thinking skills that impressed you and that you would like now to ‘eat’ by gobbling up and inwardly digesting, so that they become part of you. Write down, for instance, any key remarks or sayings by which the person concerned encapsulated his or her practical wisdom.

Exercise 5: Your personal thinking skill mentors

| Name | Thinking skill |

Take some time over this exercise, and try to get a good spread across the functions (analysing, synthesising and valuing) and the applied forms of effective thinking (decision making, problem solving and creative thinking). After all, you don’t want to eat a meal composed of just one ingredient.

You will probably find it easy to come up with the names of two or three people – a parent, a friend, a life partner or a boss you have worked for – who have exemplified a thinking skill that you covet. If it is not so easy, however, to come up with many names to complete Exercise 5, leave it for a week or two. Your Depth Mind will suggest other names and other lessons – influences that may have become more subconscious.

From your list of ‘appetising’ thinking skills you can begin to create a composite and imaginary picture of the perfect practical thinker. He or she would have A’s analytical skills, B’s rich and creative imagination, C’s ability to be flexible and improvise, D’s extraordinary judgement in situations of uncertainty and unpredictability, E’s courage to take calculated risks, F’s intuitive sense of what is really going on behind the scenes, G’s lack of arrogance and openness to criticism, H’s decisiveness when a decision is called for, and I’s tolerance of ambiguity when the time is not ripe for a decision.

Now a perfect person with all these skills – a Mr or Ms ABCDEFGHI – does not, and never will, exist. You may know the story of the young man who searched the world for the perfect wife. After some years he found her – but, alas, she was looking for the perfect husband! Perfection will always elude you – but excellence is a possibility.

What the exercise achieves, however, is to give you an ideal to aim for. Advanced thinkers in any field tend to be lopsided: like athletes, they develop one set of muscles rather than others. Did you know that sprinters are hopeless at long-distance running? I am not advocating that you should be a perfectly balanced thinker, a kind of intellectual ‘man for all seasons’. Rather, I suggest you look carefully at your field and where you see yourself positioned in it in (a) five years’ time and (b) ten years’ time. The ideal that you formulate should be related to your field, although, of course, not all your personal thinking skill mentors will be from that field – at least I hope not, otherwise I should suggest that your ‘span of relevance’ needs widening.

Check that you are in the right field

Thinking skills are partly generic or transferable, and partly situational. Decision making and problem solving are not abstracts: they are earthed in a particular field, with its knowledge, traditions, legends, and values.

Dimitri Comino, the founder of Dexion plc, once discussed with me a book I was writing on motivation. ‘In my experience,’ he said, ‘it is very difficult to motivate people. It is much better to select people who are motivated already.’ The same principle holds good, I believe, for thinking skills. It is actually quite difficult to teach yourself skills that are not natural to you. So choose a field that suits your natural profile as a thinker. What is the right field of work for you? (See the table below.)

Key factors in choosing your field of work

| What are your interests? | An interest is a state of feeling to which you wish to pay particular attention. Long-standing interests – those you naturally like – make it much easier to acquire knowledge and skills. |

| What are your aptitudes? | Aptitudes are your natural abilities, what you are fitted for by disposition. In particular, an aptitude is a capacity to learn or acquire a particular skill. Your aptitude may range from being a gift or talent to simply being above average. |

| What are the relevant factors in your temperament? | Temperament is an important factor. Some people, for example, are uncomfortable in decision-making situations of stress and your danger, while others thrive on them. Some prefer to be problem solvers rather than decision makers. |

It is usually easier to identify the fields that you are not suitable for, because you lack the necessary level of interests, mental aptitude, or temperamental characteristics to do really well in them.

Let me now make the assumption that you are in the right field. You have more or less the right profile of aptitudes. You have been able, in other words, to acquire the knowledge and professional/technical skills needed and have enjoyed doing so. You have already laid the foundations of success at the team, operational and strategic levels of leadership. You will have credibility among your colleagues. Now what you have to do is focus upon the process skills – the more generic or transferable ones – in decision making and problem solving. How do you acquire them?

How to design your own learning strategy

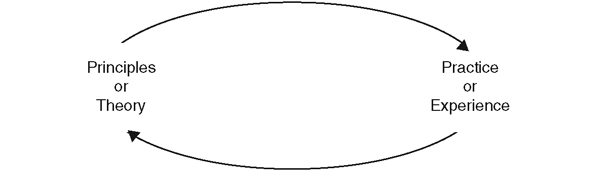

Before planning your own self-learning programme it is useful to remind yourself of the core process of learning. (See the diagram below.)

Recall what was said above about thinking skills being partly generic and partly situational. It is when sparks jump between these two poles that learning occurs. So you need both.

Figure 7.1 How we learn

Because decision making and problem solving are such central activities in any person’s life we have plenty of experience of them. And as you move into a professional field, and begin making decisions and tackling problems, you soon build up a repertoire of experience. You learn by mistakes. In the technical aspects of your work you do have a body of knowledge – principles or theory – to bring to bear on your practice. How can you apply the same learning method to thinking skills? Here are some practical suggestions:

- Read this book again and underline all the key principles. Put a star by the models or frameworks that you can use. Build up your own body of theory.

- Make an inventory of your thinking skills in relation to your own field of work. What is the present profile of your strengths, and what are the areas for improvement?

- See if you can identify three outstanding decision makers and problem solvers in your field to whom you have access. Ask if you may interview them briefly to discover what principles – if any – have informed their own development as applied thinkers.

- Select one really bad decision made by your organisation during the last 18 months. Write it up as a case study, limiting yourself to five key lessons to be learned about decision making. If you want to develop your moral courage, send it to the chief executive!

- Now select any outstanding innovation in your field, inside your organisation or outside it. By an ‘innovation’ I mean a new idea that has been successfully ‘brought to market’ as a new (or renewed) product or service. Again, write it up as a case study and highlight at the end the five or six key lessons for creative problem-solvers.

- Set yourself a book-reading programme. ‘He would say that, wouldn’t he?’ But I do not have to persuade you to read books – you have just read this one. If you have enjoyed it, and found it worthwhile, try to read one general book each year on leadership (see Further Reading for some suggestions) and one biography of an outstanding person in your field. Again, underline the key principles in pencil. Surely you can budget time for one book in 52 weeks?

- Transfer your growing body of principles, examples, practical tips, sayings or quotations, and thumbnail case studies to a stiff-covered notebook. As it fills up, take it on the occasional train journey or flight and read it reflectively, relating it to your current experience.

- Take any opportunities that come your way to attend courses or seminars that offer you know-how in the general area of effective thinking. You should, for example, become thoroughly versed in what information technology can do – and not do – at present in your field, and become skilled in the use of computers.

- Lastly, go out of your way to seek criticism of yourself as a decision maker and problem solver. However savage, however apparently negative the criticism, you still need it in order to learn. It is the toughest part of being a self-learner, but remember the sporting adage, ‘No pain, no gain.’ Your critics, whatever their motives or manners, are doing you the service of true friends. Sift through their comments for the gold-dust of truth.

In any self-learning programme, experience is going to play the major part. There is no getting away from that. But if you rely just on learning in what has been called ‘the university of experience’ you will be too old when you graduate to benefit much from the course! And the fees you will pay on the way will be extremely high. Short though it is, this book gives you those essential components – the key frameworks and principles – that you can use to cut down the time you take to learn by experience – experience and principles.

You will begin to develop both your knowledge of these process skills and your ability to apply that knowledge in all the challenging and potentially rewarding situations that lie ahead of you. Good luck!

- Knowledge is only a rumour until it is in the muscle, says a Papua New Guinea proverb. Think of your mind as a muscle – or a set of muscles. This book tells you in an introductory way how to develop those muscles, but it is you who have to put in the effort. Are you keen to do so?

- Don’t think of thinking as being hard, painful or laborious – if you do that you certainly won’t apply yourself to shaping and sharpening your thinking skills. Thinking is fun, even when – or especially when – we are faced with apparently insurmountable difficulties.

- You are more likely to be effective as a practical thinker if you succeed in finding your vocation, your right niche in the world of work. The guide here is to choose a function and field or work that is optimum for your interests, aptitudes and temperament.

- ‘I have never met a man so ignorant,’ said Galileo, ‘that I couldn’t learn something from him.’ Prize especially those people you meet – in person or in books – who can teach you things in how to think.

- Practical wisdom should be your aim as a thinker, especially in the applied domain of decision making. Practical wisdom is a mixture of intelligence, experience and goodness.

I learn most, not from those who taught me but from those who talked with me.

St Augustine