CHAPTER 6:

THE RUTHERFORD B. HAYES ADMINISTRATION

President Hayes (served 1877–81) willingly carried out the commitments made by his friends to secure the disputed Southern votes needed for his election. He withdrew the federal troops still in the South, and he appointed former senator David M. Key of Tennessee to his cabinet as postmaster general. Hayes hoped that these conciliatory gestures would encourage many Southern conservatives to support the Republican Party in the future. But the Southerners’ primary concern was the maintenance of white supremacy; this, they believed, required a monopoly of political power in the South by the Democratic Party. As a result, the policies of Hayes led to the virtual extinction rather than the revival of the Republican Party in the South.

Hayes’s efforts to woo the South irritated some Republicans, but his attitude toward patronage in the federal civil service was a more immediate challenge to his party. In June 1877 he issued an executive order prohibiting political activity by those who held federal appointments. When two friends of Sen. Roscoe Conkling defied this order, Hayes removed them from their posts in the administration of the Port of New York. Conkling and his associates showed their contempt for Hayes by bringing about the election of one of the men (Alonzo B. Cornell) as governor of New York in 1879 and by nominating the other (Chester A. Arthur) as Republican candidate for the vice presidency in 1880.

One of the most serious issues facing Hayes was that of inflation. Hayes and many other Republicans were staunch supporters of a sound-money policy, but the issues were sectional rather than partisan. In general, sentiment in the agricultural South and West was favourable to inflation, while industrial and financial groups in the Northeast opposed any move to inflate the currency, holding that this would benefit debtors at the expense of creditors.

In 1873 Congress had discontinued the minting of silver dollars, an action later stigmatized by friends of silver as the Crime of ’73. As the depression deepened, inflationists began campaigns to persuade Congress to resume coinage of silver dollars and repeal the act providing for the redemption of Civil War greenbacks in gold after Jan. 1, 1879. By 1878 the sentiment for silver and inflation was so strong that Congress passed, over the president’s veto, the Bland–Allison Act, which renewed the coinage of silver dollars and, more significantly, included a mandate to the secretary of the treasury to purchase silver bullion at the market price in amounts of not less than $2 million and not more than $4 million each month.

Opponents of inflation were somewhat reassured by the care with which Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman was making preparation to have an adequate gold reserve to meet any demands on the Treasury for the redemption of greenbacks. Equally reassuring were indications that the country had at last recovered from the long period of depression. These factors reestablished confidence in the financial stability of the government; when the date for the redemption of greenbacks arrived, there was no appreciable demand upon the Treasury to exchange them for gold.

Hayes chose not to run for reelection. Had he sought a second term, he would almost certainly have been denied renomination by the Republican leaders, many of whom he had alienated through his policies of patronage reform and Southern conciliation. Three prominent candidates contended for the Republican nomination in 1880: Grant, the choice of the “Stalwart” faction led by Senator Conkling; James G. Blaine, the leader of the rival “Half-Breed” faction; and Secretary of the Treasury Sherman. Grant had a substantial and loyal bloc of delegates in the convention, but their number was short of a majority. Neither of the other candidates could command a majority, and on the 36th ballot the weary delegates nominated a compromise candidate, Congressman James A. Garfield of Ohio. To placate the Stalwart faction, the convention nominated Chester A. Arthur of New York for vice president.

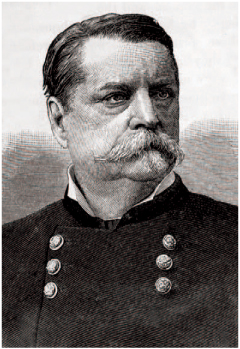

The Democrats probably would have renominated Samuel J. Tilden in 1880, hoping thereby to gain votes from those who believed Tilden had lost in 1876 through fraud. But Tilden declined to become a candidate again, and the Democratic convention nominated Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, who had been a Federal general during the Civil War. Hancock had no political record and little familiarity with questions of public policy.

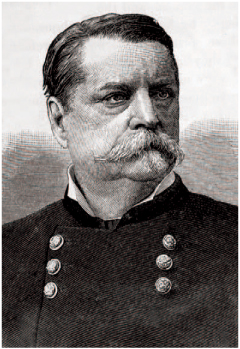

John Sherman, who was secretary of the treasury under Pres. Rutherford B. Hayes. Sherman also vied for the Republican presidential nomination in 1880, 1884, and 1888. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Civil War Union general and Democratic presidential nominee Winfield S. Hancock. Bob Thomas/Popperfoto/Getty Images

The campaign failed to generate any unusual excitement and produced no novel issues. As in every national election of the period, the Republicans stressed their role as the party of the protective tariff and asserted that Democratic opposition to the tariff would impede the growth of domestic industry. Actually, the Democrats were badly divided on the tariff, and Hancock surprised political leaders of both parties by declaring that the tariff was an issue of only local interest.

Garfield won the election with an electoral margin of 214 to 155, but his plurality in the popular vote was a slim 9,644. The election revealed the existence of a new “solid South,” for Hancock carried all the former Confederate states and three of the former slave states that had remained loyal to the Union.