CHAPTER 1

Labrador Inuit Ingenuity and Resourcefulness: Adapting to a Complex Environmental, Social, and Spiritual Environment

Susan A. Kaplan

This chapter discusses how, over the course of 500 years, the Thule ancestors of today’s Labrador Inuit effectively responded to the geography of the region, as well as to environmental and social changes that presented them with both challenges and opportunities. The chapter also explores ways in which Inuit might have dealt with spiritual dangers presented by Labrador’s forested landscapes, which were unfamiliar to them and possibly harboured powerful beings.

The first part of this chapter reviews the major settlement pattern shifts undertaken by Labrador Inuit groups and provides an economic view of the flexibility Inuit exhibited from the time they first occupied coastal Labrador to the nineteenth century. The chapter then looks closely at the life of one eighteenth-century household, examining its use of the region’s marine and terrestrial resources, including plants. The chapter concludes by discussing some of the spiritual concerns Inuit might have faced as they encountered forested land and how they might have dealt with those challenges. The chapter suggests that Inuit might have spiritually adapted to Labrador by deforesting tracks of land around their sod house settlements, thus domesticating the landscapes around their homes and moving a potentially dangerous environment away from their families.

Inuit Adaptations to Labrador, the Broad Picture

Moving into the Region

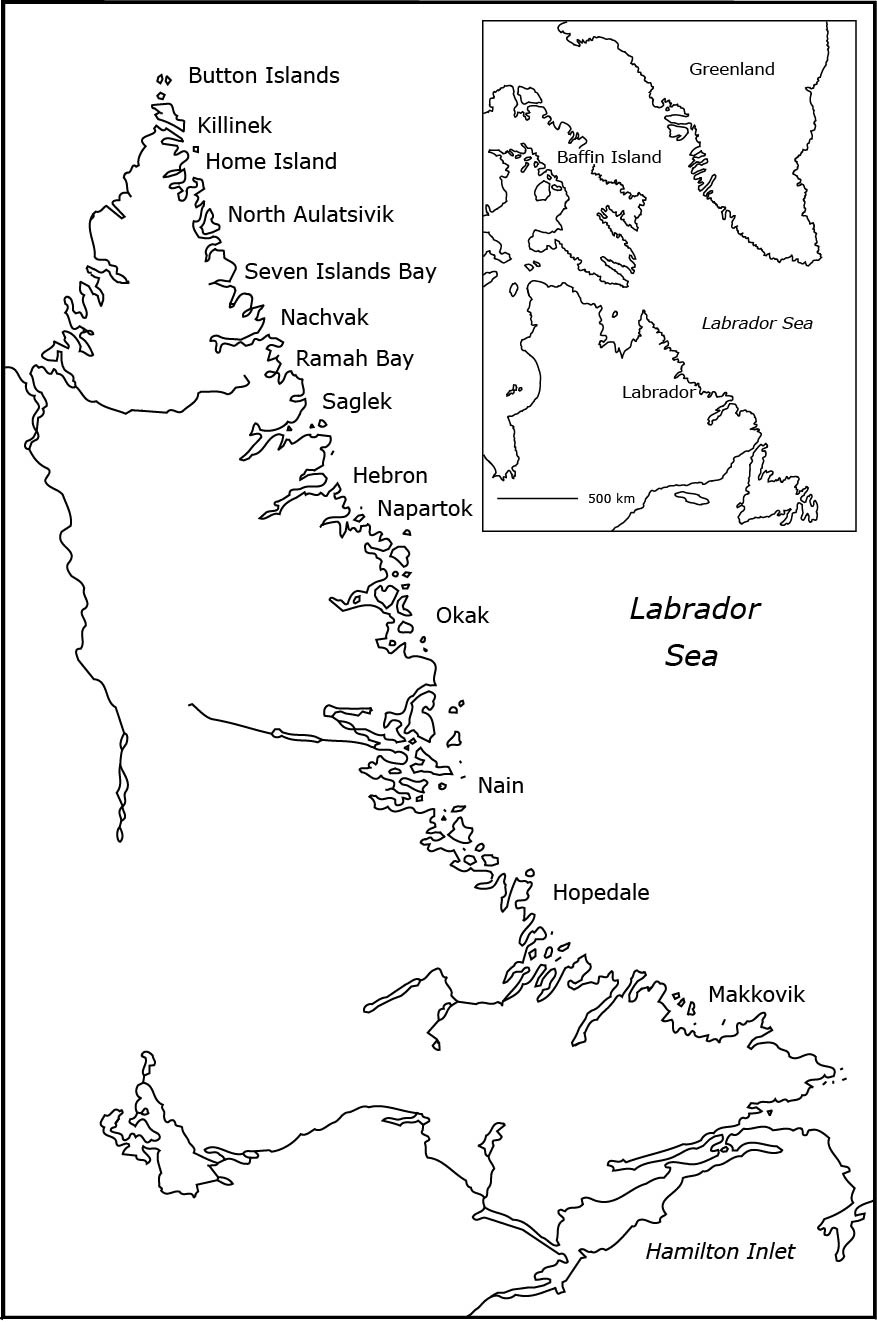

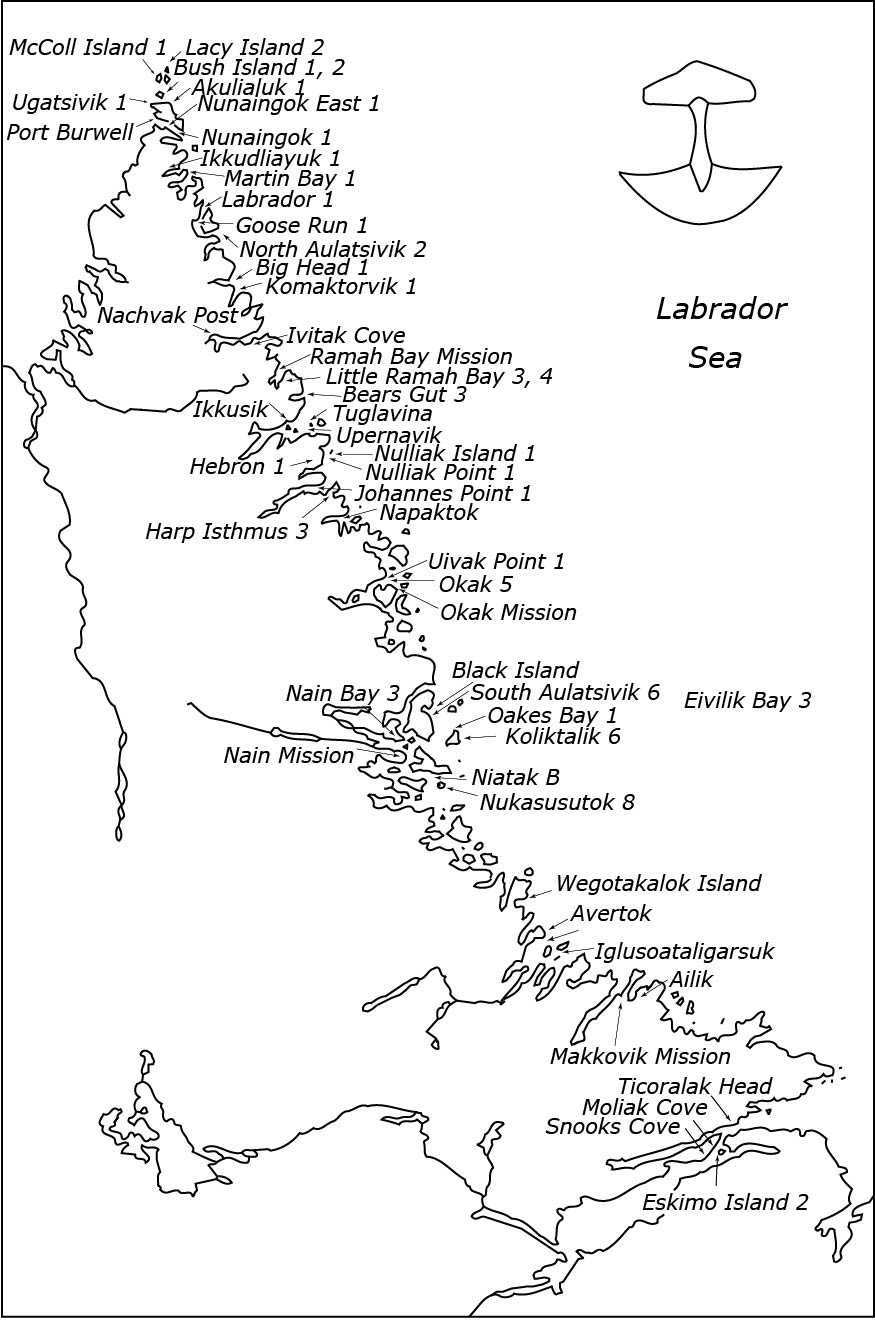

Thule people began settling northern Labrador around the end of the thirteenth century CE (Fitzhugh 1994, 253). Whether the newcomers travelled from Baffin Island via the Button Islands or from areas further west is not yet known (see Figure 1). Northern Labrador had been inhabited previously by Maritime Archaic and various Paleoeskimo groups, including, most recently, groups known archaeologically as the Late Dorset people. Archaeologists do not yet know whether Late Dorset groups were living in Labrador when Thule people arrived, for clear material evidence of contact remains archaeologically elusive (Fitzhugh 1994).

Figure 1. Map of Labrador.

Labrador’s Thule migrants arrived with sophisticated strategies, techniques, and technologies with which to hunt, gather, and process foods, as well as make the clothes, boats, shelters, implements, and weapons they needed. Very small pieces of ground and drilled fine-grained slates (fragments of harpoon endblades, and knife and ulu blades) found in early north coast sites, and the absence of fine-grained debitage (debris left after making an implement) suggest that Thule families brought their equipment with them to Labrador hoping to replace it once they knew where to find certain resources (Kaplan 1985, 50). In some northern sites the fine-grained slate tool fragments appear along with coarse-grained slate objects and debitage. The presence of coarse-grained slates that are local to the area suggests that relatively soon after settling in Labrador people found and began using local lithic resources.

If archaeologists can pinpoint the sources of these and other raw materials the newcomers used to make their slate tools, soapstone pots and lamps, sandstone whetstones (grinding and sharpening stones), and ground nephrite endblades and drill bits, they might be able to discuss where the groups migrated from and the speed with which the newcomers found and began to use local resources. There is the possibility that Thule people learned the locations of local lithic sources and figured out where productive living and hunting sites were situated by finding remains of previous occupants’ quarrying activities, structures, and hunting and butchering sites.

Many of northern Labrador’s general features—tundra-covered hills with bedrock outcrops, bold headlands and gently sloping beach passes, fast-running rivers cutting through complex mountain valleys, deep fjords and bays, and near-shore and offshore islands—would have been familiar to the newcomers, though they would have had to learn the particular geography of the region. They would also have known about the ice foot, the sina (ice edge where fast ice and open water meet), rattles (areas with swift currents that make a rattling noise and that remain open much of the year), polynyas (large areas of perennially open water formed by swift currents and wind action), and pack ice. However, the boreal forests growing as far north as Napaktok Bay would have presented Thule people with a new and unfamiliar environment.

The Inuit would have had much to learn about Labrador, including what animals were attracted to specific sections of the coast, because game is not uniformly distributed throughout the peninsula. Also, they had to observe the seasonal movements of their prey. For instance, bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus), the largest of Labrador’s seals, spend the winter months along the floe-edge and in pack ice, and enter fjords and bays in the spring to feed on cod. They are generally unavailable to Labrador hunters in the summer, when the seals swim to cool waters north of Labrador (Boles 1980, 56, 66; Schwartz 1977, map 87). Harp seals (Phoca groenlandica) are around Labrador twice a year. They swim up the coast in late April and early May en route to Baffin Bay and the Davis Strait region, where they spend the summer. They return to Labrador in the fall, entering the region’s bays and fjords in pursuit of cod and capelin (Banfield 1974; Boles 1980; Pinhorn 1976). In contrast to the gregarious migratory harp seal, the solitary ringed seal (Phoca hispida) remains in Labrador waters year round. It builds birthing lairs or dens in the fast ice. In the winter and spring, mature animals tend to maintain breathing holes in the fast ice, while the immature animals frequent polynyas and the ice edge (Boles 1980, 29; McLaren 1958, 60).

Settling In

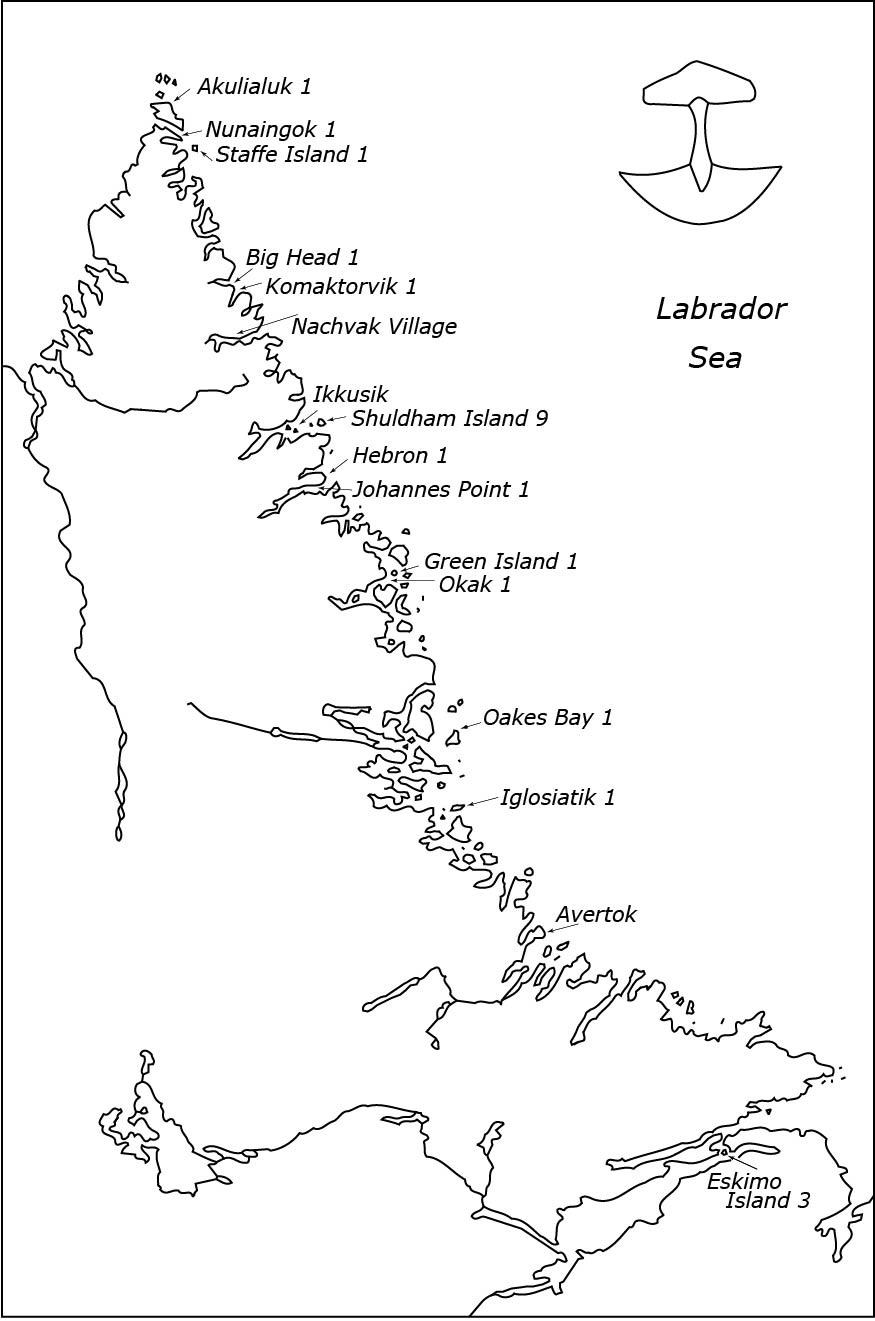

The Thule people built small, four-metre by six-metre, oval-to-rectangular (or bi-lobed) semi-subterranean sod houses, with long entrance tunnels equipped with cold traps. Initially, they chose to construct these on far outer islands and outer sections of fjords and bays. These locations placed the sod-house settlements close to the sina or near rattles and polynyas , all places where hunting marine mammals was very productive in the winter and spring. For instance, they built sod houses along the southern shore of McLellan Strait, a constricted waterway between the tip of Labrador and Killinek Island and the location of a major polynya. They also built sod houses on the north shore of Nachvak Fjord, where it joins Tallek Arm, an area where a small polynya appears most years. Sod house clusters from this early period have been located on outer islands, such as Staffe Island in northern Labrador (Kaplan 1983; Fitzhugh 1994), Green Island and Okak Island in the Okak region (Cox 1977; Kaplan 1983 and 2009; Kaplan and Woollett 2000; Woollett 2003), and Iglosiatik Island in the outer portion of Voisey’s Bay (Kaplan 1983). Early period sod house sites have been found in the Hebron (Kaplan 1983) and Hopedale (Bird 1945) areas as well (Figure 2). People hunted bowhead whales, walrus, seals, polar bears, and birds from these locations. The Inuit probably felt quite comfortable in these places; the tundra-covered landscapes and the open seascapes and icescapes resembled more northerly regions from which they had migrated, and they would have been familiar with the game available to them in these exposed coastal locations.

Figure 2. Thule sod house sites along the northern and central coast of Labrador.

New, Exotic, and Useful Things

Inuit continued their exploration of the coast throughout the 1500s and 1600s, venturing into southern Labrador—as is evident from sod house sites on Eskimo Island in Hamilton Inlet (Jordan 1978; Jordan and Kaplan 1980) and in Snack Cove in the Sandwich Bay region (Brewster 2008), as well as from structures further south (see Rankin et al. in this volume as well as Stopp 2002 for an extended discussion of southern Labrador archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence). Some of these forays were probably staged from Avertok, the major whaling settlement in the Hopedale area. In the process of establishing themselves along the coast, the Inuit encountered another ethnic group, known archaeologically as the Point Revenge Indians (Fitzhugh 1978; Loring 1992). How these two groups reacted when encountering one another is not known. The Point Revenge presence clearly did not dissuade the Inuit, however. They appear to have been drawn south by hunting opportunities (Trudel 1980) and by growing knowledge of the existence of exotic objects brought to the New World by Basque whalers, who began to frequent southern Labrador around the time the Inuit were moving down the coast (Barkham 1977, 1978, 1980; Kaplan 1985; Logan and Tuck 1990).

We do not know when Inuit and Basque first met. Initially, the Inuit may have happened upon discarded or stored Basque materials (metals, hardwoods, roofing tiles, glass and ceramic sherds, etc.) before coming face to face with the strangers. As is evident in historic records (Barkham 1980) and on Eskimo Island, where Basque materials were recovered from inside a sod house (Kaplan 1983), the Inuit realized how useful these new materials could be and quickly made use of them. Inuit adopted Western-made metal fishhooks and lead sinkers, leaving them unmodified, while reworking other materials. For instance, they cold hammered large spikes into harpoon heads, fashioned fragments of roofing tiles into whetstones, and cut and sharpened thin pieces of iron that they made into end blades, knife blades, and scrapers. Sherds of glass and ceramics, clothing fasteners, coins, cuff links, beads, and other such objects were collected as curiosities and would eventually become prestige items to be prominently displayed on clothing or incorporated into jewellery. Inuit all along the Labrador coast soon desired these exotic materials, particularly the iron, which quickly replaced slate.

Within 200 years of their arrival in Labrador, the Thule people had explored the coast and figured out where best to live, how to make a living, and where to find the raw materials they needed. Along the way they encountered at least three different ethnic groups on land: the Late Dorset, Point Revenge, and Basque. Dutch traders were plying Labrador waters as well, and while they have not been identified archaeologically in Labrador, they would have added to the number of exotic goods entering Inuit exchange systems (Kaplan 1985, 55). The nature of the relationships between Inuit and these groups remains unclear. It is evident, however, that Inuit came to dominate most of coastal Labrador and quickly and creatively incorporated Western goods into their toolkits.

New Approaches to the Land and Resources

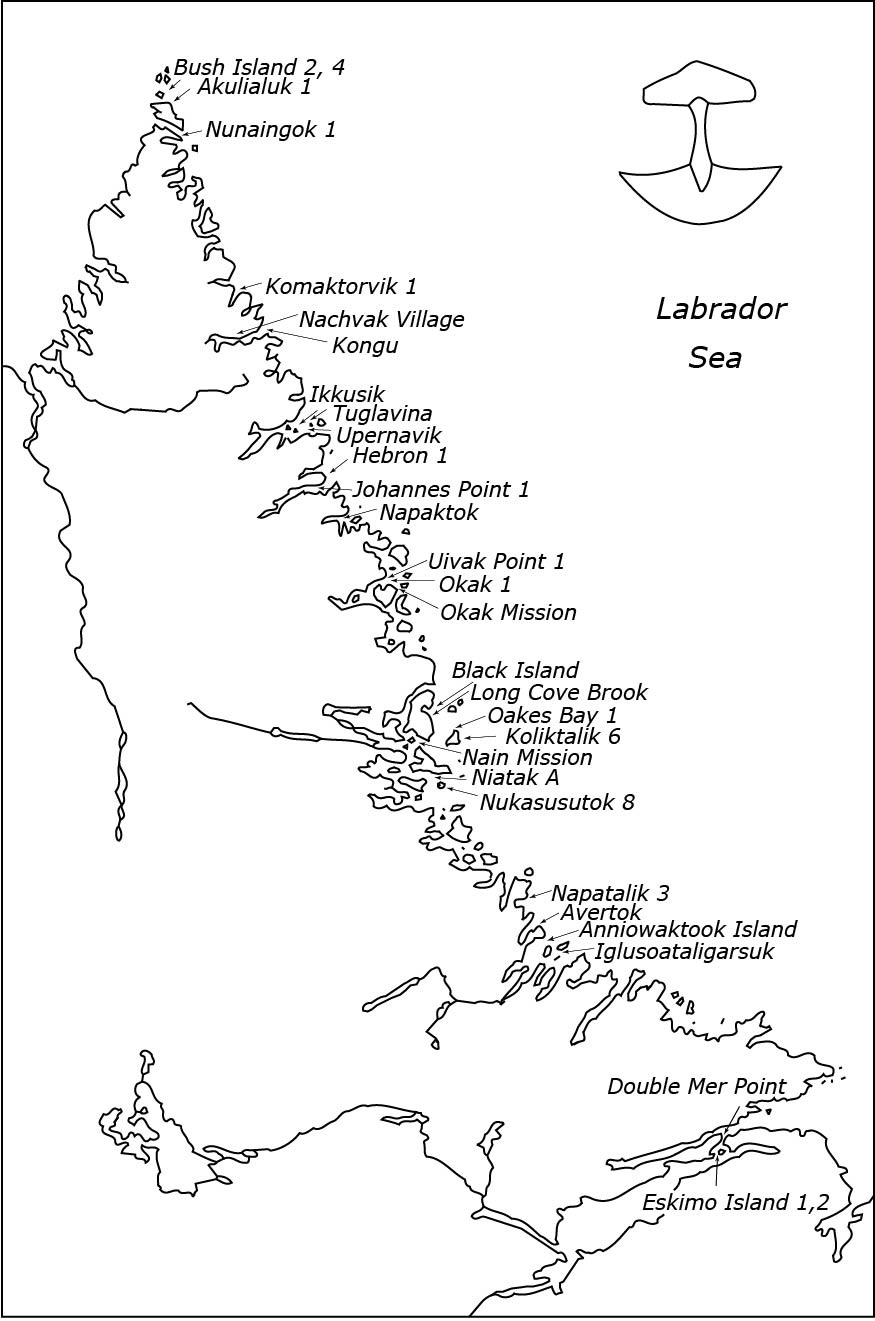

The successful settlement of Labrador resulted in a growth in the size of the resident Inuit population, and in all likelihood certain families preferred and became associated with specific sections of the coast. Some time in the late 1600s or early 1700s, northern and central Labrador Inuit shifted the locations of their sod house settlements from far outer islands to more protected and centrally located inner islands and mainland locations, places such as Ikkusik Island in Saglek Fjord, Nuasornak Island in Okak, Nukasusutok Island and Dog Island in the Nain region, and Uivak Point on the mainland in Okak. Resource-rich areas such as McLellan Strait, Hebron, Okak, and Hopedale continued to be occupied more intensively while the landscape filled up, with sections of the coast such as Nain and Makkovik becoming home to eighteenth-century groups (Kaplan 1985; Loring and Rosenmeier 2005; Taylor and Taylor 1977) (Figure 3). A variety of factors contributed to this settlement shift, which also involved changes in house form and an increase in the size of households and communities.

Figure 3. Eighteenth-century Inuit sod house sites along the northern and central coast of Labrador.

Possible triggers for changes in settlement location might have been access to food supplies and a population increase. Outer islands would have been wonderful places to live in the winter and spring under favourable circumstances, but if animals were scarce or stormy weather destroyed the fast ice, preventing people from hunting and travelling, families could have been trapped on those outer islands. If they had not stored adequate supplies of food and blubber (used as fuel for cooking and lighting), hardship would have resulted. If populations were growing, it would have become increasingly difficult to store enough reserve food.

In addition, first the Basque, then the Dutch, and finally a variety of other groups carried out intensive commercial whaling, such that the North Atlantic was depleted of large numbers of whales (Romero and Kannada 2006). Inuit probably noted a drop in availability of these large marine mammals and intensified their hunting of seals. By shifting their winter houses from extreme locations to more central places, hunters had a broader range of hunting options. They could travel to the ice edge to hunt bearded seals and young ringed seals, exploit basking ringed seals and—later in the spring—their pups in inner waterways, and reach the mainland to go caribou hunting or ice fishing at interior lakes. They could also more easily visit one another from these central places, using protected routes when necessary. The ability of communities to reach one another created a social safety net essential when a household or an entire community experienced food shortages. Thus it would have been possible to support larger numbers of people in these central places than on outer islands.

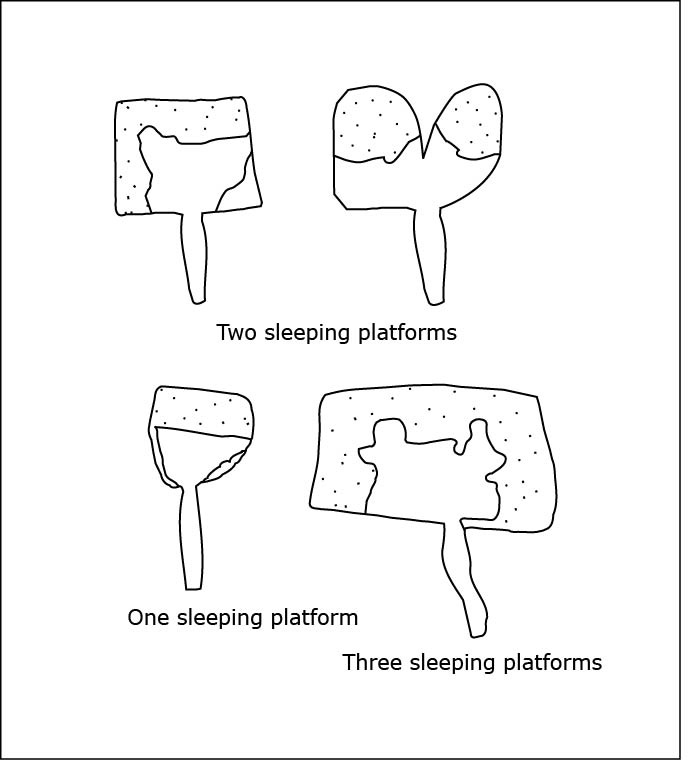

The sod house sizes changed as well. The earliest houses were built with one raised sleeping and sitting platform, usually fashioned out of sands and edged in stone. A variety of household activities would have taken place on this platform (see Briggs 1970 for an ethnographic description of household activities that took place around sleeping and sitting platforms). A stand for a soapstone lamp, a kitchen area near the house entrance, and storage compartments completed the house (Figure 4). Each house containing a single platform was probably home to between four and eight related people. Early sites usually contain a handful of sod house remains, so an outer island settlement might have supported twenty to thirty people.

Figure 4. Sod house forms.

By the mid 1700s the Labrador Inuit were building largely rectangular semi-subterranean sod houses, referred to in the literature as “communal houses,” ranging in size from 7 metres by 6 metres to 16 metres by 8 metres. The sod houses were still equipped with entrance passages and cold traps and, like earlier houses, exhibited tightly paved stone slab floors. Typically the houses were furnished with two or three sleeping platforms and multiple lamp stands (Figure 4). The Moravian missionaries travelling through the region in the eighteenth century reported that each house was occupied by an average of twenty people, though some were home to up to thirty-five people (Taylor 1974), and a number of sod houses in a community were occupied at the same time. The Moravians observed that a household typically consisted of a father, his married sons, and their wives and children. A number of men had two and sometimes even three wives. People in a house were involved in cooperative hunting and trading ventures, with the father being the key figure in the house. This concentration of people probably provided needed labour for whale hunting, which continued even though fewer whales were being caught than previously, and for long-distance trading enterprises (see Kaplan 1983; Kaplan and Woollett 2000; Taylor 1974 and 1988).

Stresses and New Opportunities

During the period of communal or multi-family-house living, a growing number of French and British traders and cod fishermen, attracted by the region’s natural resources, visited Labrador’s southern shore. Inuit continued to make journeys to southern Labrador, and indeed a long-distance trade developed in which baleen, furs, and feathers were traded south by Inuit in exchange for metals (on which Inuit were now totally dependent), firearms (highly desired by hunters), hardwoods, and items such as glass beads (symbols of prestige). Some face-to-face interactions were straightforward trading ventures, while others resulted in altercations between Inuit and Westerners as Inuit grew bolder in their pursuit of goods (Kaplan 1985, 64). The result was violence that depressed the Western fishery. In addition, Inuit men, in particular, were losing their lives in boating accidents on these long-distance voyages, in altercations, and probably as a result of communicable diseases introduced by the Westerners. A shortage of men might have been one reason men on the north and central coast had multiple wives. Aside from the economic benefits mentioned above, polygamy could have been a means of caring for relatives left without a hunter in the house.

More Newcomers

Members of the Unitas Fratrum first visited Labrador in 1752 and established a mission station in the Nain region in 1771. Referred to as Moravians, they had already worked amongst Inuit in Greenland, and they arrived in Labrador able to converse in Inuktitut. The Moravians were the first Westerners to take up residence among Inuit of the central coast. They established additional mission stations in Okak and Hopedale in the late 1700s as they sought to bring Christian beliefs to the population. They incorporated trading stores into their mission stations, hoping these would both attract Inuit to the mission and curtail the southern voyages (Whiteley 1964). Initially this strategy did not work because the missionaries refused to provide firearms to Inuit, and people thus continued their forays south. Over time, however, Inuit traded with the Moravians, worked for them, and came to rely on them as another safety net in times of food shortages (see Evans in this volume).

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), a major British-based trading empire, established a presence in Labrador in the 1830s and tried to muscle out other traders already established in the Hamilton Inlet area. In 1852, when Donald Smith (later Lord Strathcona) took charge of the Labrador HBC posts, he turned his gaze to the north Labrador coast and began to compete openly with the Moravians, whose trading enterprises had continued to expand. Smith aggressively established posts along the northern coast one decade later (Kaplan 1983, 180–83). The HBC encouraged Inuit to trap fox, exchanging the fox furs for ammunition, metal traps, and dry goods. The Moravians responded to the HBC advance by building more mission stations, and the two organizations leapfrogged their way up the north coast (Figure 5). Each tried to demand Inuit loyalty to their organization, to the exclusion of the other, through a process of inducements and threats (Brice-Bennett 1981; Kaplan 1983).

Figure 5. Nineteenth-century sod house sites along the northern and central coast of Labrador.

By the late 1800s Inuit had changed their settlement locations and house forms for a second time. Many nuclear families built small sod and above-ground houses in close proximity to Moravian mission stations or HBC posts. (The Moravians had been encouraging use of above-ground houses, considering the semi-subterranean sod houses unsanitary, and had been discouraging polygamy.) The non-Aboriginal settler population had moved into sections of the north coast that Inuit had never occupied because of poor living and hunting conditions, most notably Ramah Bay, and the Inuit followed (Kaplan 1983). A new settlement pattern emerged, based not on natural resource access alone, but on access to mission stations and trading posts. As a result, three populations of Inuit emerged along the north coast: those who expressed loyalty to the missionaries and lived in proximity to the stations, those who traded regularly with the HBC and lived near them, and those who wanted to maintain their distance from all settlers. This last group lived in the Komaktorvik area and further north and were of concern to the missionaries and Nachvak HBC factor (Kaplan 1983). The unified, long-distance trade networks that characterized the eighteenth century were no longer tenable, large sea mammal hunting opportunities had disappeared, and traditional social safety nets had been disrupted, particularly between converts and the rest of the population (Brice-Bennett 1981).

Inuit material culture continued to be used; though, as noted earlier, slates were entirely replaced by metals. By this time firearms had replaced the bow and arrow, and metal fox traps had been introduced, as had sealing nets. Ceramic cups and bowls had become household items, and in some cases were used instead of soapstone vessels (Loring and Arendt 2009; Loring and Cabak 2000).

Flexibility and Resourcefulness

As is evident from the above discussion, the Thule Inuit who moved into coastal Labrador quickly adapted to the region. Over the course of the next 500 years they repeatedly responded to environmental and social changes. Local exchange and sharing networks were augmented in the eighteenth century by a unifying long-distance trade network. That network was abandoned when groups developed relationships with local traders and missionaries. Inuit assessed the utility of European goods and quickly adapted new technologies to meet their needs. While Inuit had to change the focus of some of their hunting due to the overhunting of large marine mammals by commercial whalers, individuals did not specialize. They maintained a generalized adaptation that involved making use of the range of resources available to them to feed their families. These resources included animals they hunted and trapped, traditional sharing networks, and reliance on European establishments.

This ability to adapt to changes, environmental and social, by maintaining a diversity of skills, as well as mental and social flexibility to adjust lifestyles, are the defining characteristics of the Labrador Inuit. Today, people are concerned about the warming of the Arctic and the impact of rapid cultural change resulting from increased influences from the outside. It is in this contemporary context that the Thule/Labrador Inuit history of flexibility and ingenuity might be most instructive.

An Eighteenth-century Home

This broad view of Labrador Inuit settlement history is useful, but it is limited as well. It is a picture pieced together using data derived from archaeological surveys, some excavations, and interpretations of historic records. The above sketch is lacking in a few key ingredients because it centres mostly on economic considerations and is largely maritime focused. This section of the chapter will take a close look at an eighteenth-century household based on examination of a sod house at Uivak Point, in the Okak region, where eighteenth-century communal houses were built. The discussion will reveal the extent to which Inuit learned to use not only marine but also terrestrial resources of the region and, in doing so, learned to make a house a home and live a bountiful life.

Examining an Eighteenth-century House

In order to develop a detailed picture of what life would have been like for one group of Inuit living in a large communal house in the late 1700s, a semi-subterranean sod house in the Okak region was excavated (Figure 3). The sod house site, located on the mainland directly across from Okak Island, is known in the Provincial Archaeology Office records as Uivak Point 1 (HjCl-09). The archaeology site’s name is redundant, since uivak means “point” in Inuktitut, and is probably a reference to the point of land on which the sod houses were built. Moravians who visited the community recorded its name as Uibvak or Uivakh (Taylor and Taylor 1977). Uivak was one of three eighteenth-century Inuit whaling settlements in Okak. Uivak Point 1 includes the remains of nine semi-subterranean sod houses built into a raised beach on the protected southwestern shore. The sod houses, as well as tent rings, hunting blinds, graves, route markers, caches, extensive middens, and outdoor hearths, testify to the intense use of this area.

The hills above the sod houses offer a panoramic view of the open North Atlantic as well as expansive views of the protected waterways of inner Okak Bay. From these hills people probably watched for and intercepted migrating bowhead whales and harp seals, could spot sunning and denning ringed seals found in the stable ice in inner Okak Bay, and looked for a variety of sea mammals at the sina, which was close by.

Three-fourths of House 7 and a large portion of its midden were excavated. The work revealed that House 7 was an eighteen-metre by twelve-metre structure, truly a large house (Kaplan 2009; Kaplan and Woollett 2000; Woollett 2003 and 2007). The thirty-two one-square-metre excavation units exposed House 7’s entrance passage, cold trap, and house floor, which were nicely paved with large flat stones chinked with smaller paving stones, revealing the care that went into the structure’s construction. A raised sleeping platform ran the entire length of the back wall of the house, and a second platform ran along portions of a side wall. Lamp stands fashioned out of stone and whale vertebrae were identified as well. The interior features suggest at least two related families lived together in the house.

Collapsed house posts and beams, some made out of whale ribs, one out of a whale scapula, and others out of wood, were uncovered in the house and entrance passage. Cast-off wooden structural supports were also recovered in the midden. The use of whale bones as supports was pragmatic but also probably had a spiritual significance, given the close association of whales, women, and houses, as found in north Alaska and the Canadian high Arctic (see, for instance, Bodenhorn 1990; Savelle and Habu 2004).

Inuit-made artifacts fashioned out of bone, antler, walrus ivory, baleen, hide, and wood were recovered from the house and midden. The artifacts include hunting implements such as toggling harpoon heads, harpoon socket pieces and finger rests, float inflation nozzles and wound plugs, bow fragments, and knife handles. Dog harness traces and toggles, pieces of sled runners, kayak and umiak parts, and bone paddle tips were among the types of objects recovered. These are remains of implements that the occupants of House 7 used when they hunted and travelled on land, in open water, along the ice edge, over snow-covered terrain, and on the sea ice.

Bucket and bowl bottoms, a wooden bowl carved out of a burl, fragments of stitched hide, ulu handles, decorative pendants, soapstone pot and lamp fragments, a wooden doll, a toy wooden bear, a comb, and mattock blades hint at the many domestic activities taking place in and around the house.

European-manufactured materials were used along with traditional materials in the subsistence and domestic spheres. Found items include glass beads, a mouth harp, a metal thimble, fine-toothed ivory combs, glass buttons, a coin, sherds of decorated earthenware, kaolin pipe fragments, pieces of bottle and window glass, a glass door knob, iron nails and spikes, metal knife blades, gun flints, lead shot, firearm parts, and iron bowl fragments. Pieces of metal were inserted into harpoon heads and fashioned into knife and ulu blades; pipes were used for smoking tobacco. Metal thimbles were used in addition to the traditional leather variety; fine-toothed manufactured combs were used along with hand-made combs. Beads adorned clothes and earrings. This inventory reveals the extent to which exotic goods had been incorporated into many facets of Inuit life. The European-made objects suggest that the house dates to the late eighteenth century. This date is in keeping with Moravian accounts that document people living at Uivak between the 1770s and 1790s (Kaplan and Woollett 2000; Taylor and Taylor 1977, 60; Woollett 2003).

Jim Woollett, a zooarchaeologist, analyzed the 52,543 animal bones recovered from the House 7 midden. His analysis supports the subsistence picture suggested by the artifacts. Over 70 percent of the 26,769 identified bones belonged to sea mammals. Ringed and harp seals, the one ice dependent and the other open-water dependent, were the most frequently hunted animals, with harbour and bearded seals appearing in fewer numbers (Woollett 2003 and 2007). Fish, mussels, birds, caribou, and fur-bearing animals were additional food resources. Bones from large whales were found at the site as well. Moravian missionaries reported that people in the Okak region caught a whale every few years. This suggests that these large marine mammals were valuable but not dependable sources of food. When one was caught there was cause for great celebration, and communities from surrounding areas shared in the catch. The procurement of a whale reinforced the whalers’/hunters’ sense of identity, while the celebration and distribution of meat brought to light the kinship ties and networks of mutual aid between communities.

The faunal remains and artifacts indicate that Uivak House 7 inhabitants hunted in a variety of environments and practised an economy generalized in scope; they procured a diversity of animals, most harvested from the sea. Woollett extracted well-preserved teeth from recovered seal jaws and examined tooth-thin sections in order to determine the age of the seals, when they died, and during what season they were killed. His season-of-death estimates indicate that the people living in House 7 hunted the various seals when the animals were most accessible. For instance, harp seals were intensively hunted in the fall, when they lingered close to shore, adult ringed seals were hunted at breathing holes throughout the winter, and young ringed seals were a focus in the spring, when they emerged from their dens in the fast ice (Kaplan and Woollett 2000; Woollett 2003 and 2007).

In all likelihood, Uivak was not occupied in late summer, or if it was, people lived in tents, given that the sod houses would have been unpleasant places at that time of year. Fall is the time when caribou are in their prime, and families probably moved to places where they could reliably intercept large numbers of these animals. They would dry and cache the meat and process the skins, which would be made into warm fur clothes and bedding. This would account for the few caribou bones found in the sod house midden.

Archaeological Puzzles

House 7 contained well-preserved wooden support beams. Analysis of the growth rings in the beams was undertaken to learn more about how the local climate changed over time. This helped researchers understand how Labrador Inuit had responded to the North Atlantic’s dynamic climate conditions, particularly the Little Ice Age. Also, two distinct occupation periods of House 7 were identified using a combination of tree ring data and the historic artifacts; one occupation dated from 1772 to 1780, the other from 1792 to 1806 (Woollett 2003).

Existing climate records from the late 1700s revealed that Inuit had inhabited House 7 during a cold, but environmentally stable, period that was followed by a period of severe cold. These findings and the results of archaeological and faunal analyses, as well as Moravian accounts that Inuit maintained large dog teams (which would have required a great deal of meat to support), indicate that the inhabitants of Uivak enjoyed a bountiful life. Why was the site abandoned? Was it because of the 1800 cold snap or the dwindling number of whales? Did the collapse of the long-distance trade network or the proximity of the Okak Moravian mission station, established in 1776, have anything to do with the site’s abandonment? Hopefully, future research will produce answers to these questions.

Twisted Wood, Twigs, Seeds, and Beetles

Archaeologists working in Labrador have generally been most interested in questions of economy of maritime hunters. Until the excavation of House 7, Inuit relationships to Labrador’s terrestrial environment had not been considered. As a result, the archaeological reconstructions of Inuit economy are probably under-representing the terrestrial component of the Inuit diet. Also, the reconstructions are overlooking contributions of important segments of the Inuit population, namely the women, children, and elders who would have been harvesting many of the land-based resources.

House 7 yielded a great deal of spruce wood that was twisted and gnarly. The wood was from white spruce (Picea glauca) krummholtz. Krummholtz are highly stunted, slow-growing trees (Figure 6). Their growth rings are very dense, and as a result the wood is very strong. The occupants of House 7 at Uivak harvested krummholtz and used them, as well as whale bone, to support their large dwelling. Whether this was the only wood available, or whether Inuit selected it for its strength, we do not know (see Payette et al. 1985 for discussions of krummholtz in Labrador and Quebec).

Figure 6. Photographs of a krummholtz and twisted wood.

Bulk soil samples from the sleeping platform, interior house floor, entrance passage, and midden were collected for further analysis in a laboratory setting. Cynthia Zutter (2000 and 2009) examined the plant remains (called macrobotanical remains) in these samples and those from an off-site location. Analysis of the turf collected from the sleeping platform revealed that this wooden platform had been covered with a variety of spruce, crowberry, willow, and birch boughs (Zutter 2009). In all likelihood the boughs provided insulation and padding for the families that slept on the platform under fur blankets. The soils collected from the house floor and entrance passage included crowberry and birch twigs in addition to spruce needles (Zutter 2000 and 2009). The house occupants might have spread the twigs and needles on the floor to collect grease and food particles, and perhaps to freshen the house. The twigs and needles also would have prevented objects left on the paved floor from freezing to the stone. Discrete piles of household debris, including twigs and spruce needles, were found in the midden and probably represent house floor sweepings tossed out the door after a cleaning.

Zutter also identified high concentrations of crowberry, bearberry, and blueberry seeds throughout the house and the midden. The presence of these thousands of seeds in the midden in particular suggests that the berries had been eaten and the seeds deposited into the midden in human feces, also identified at the site (Zutter 2009).

Allison Bain (2000) recovered fly and beetle remains in the soil samples from House 7. Her study of insect remains (paleoentomology) focused on the beetles. Within the house she identified varieties of beetles that were unknowingly brought into the house when people carried in freshly cut wood for use as posts and beams, and boughs and mosses for use on the floor and sleeping platforms. These included ground beetles typically found in conifers and mosses, bark beetles usually attracted to recently cut wood, and rove beetles found in willow and alder-leaf litter.

The plant and insect remains found in the soils in the house and midden suggest that the inhabitants of House 7 harvested berries intensively in the late summer and fall, possibly prior to moving into the house. They probably stored large quantities of the fruits, which they consumed later in the winter. They also cut down trees and gathered tree branches, bush, and mosses from areas surrounding Uivak on an ongoing basis. Due to preservation issues and the season when the house would have been occupied, soft tissue plants that might have been harvested by Uivak residents in the early fall for use as food or medicine have not been recovered. E.W. Hawkes (1970, 35–37) discusses a variety of leafy plants collected for those purposes. Despite the lack of archaeological evidence of most soft tissue plants, it is clear that the inhabitants of House 7 used plants regularly to make their home comfortable and to supplement their diet. In all likelihood, women, children, and elders did the vital, hard work of collecting the plants. In addition, wood was used in house construction, and probably also to build drying racks and kayak and umiak stands, although these structures have not been identified archaeologically at Uivak.

Adapting to Forested Areas

The site of Oakes Bay 1 (HeCg-08) on Dog Island in the Nain region is also an eighteenth-century communal house site. Known as Parngnertokh (Taylor and Taylor 1977), the site consists of seven discrete semi-subterranean houses. The Oakes Bay 1 middens are shallow, suggesting that the site was not occupied intensively or for a long period of time. The sod houses are on a tundra-covered expanse with a thin scattering of krummholtz spruce on the hillside behind the site. Across the bay from Oakes Bay 1 are dense stands of spruce. Upon consideration, archaeologists realized that the land on which Oakes Bay 1 is located was probably once heavily forested as well. Areas would have been cleared of trees to make room for the sod structures and the wood used to build and furnish the homes, and for numerous other uses such as making drying racks.

Analyses of tree stumps found amongst the krummholtz behind the site reveal that a number of trees were cut in the early twentieth century (Rosanne D’Arrigo 2001, pers. comm.). Today trees around Oakes Bay are being cut for firewood by Nain residents. Here, then, is an example of a landscape gradually being transformed from forest to tundra by human deforestation.

The Uivak site has no trees in its vicinity at present (Figure 7), but like the Oakes Bay site, forested areas exist nearby, such as across the bay from the Uivak site, as well as further west. Extensive middens suggest that Uivak was more intensively occupied than Oakes Bay. Did the occupants of Uivak deforest the area around their settlement? S. Payette et al. (1985) discuss a massive mortality of old spruce in the late 1800s as a result of climate changes. The lack of trees in the Uivak area itself and thinning at the Oakes Bay site do not appear to be related to climate-caused die-off, but rather to human activities. The tree harvesting raises additional questions about Inuit adaptations to forested regions of Labrador.

Figure 7. Tundra-covered pass and Uivak Point 1.

A Land of Plenty Harbouring Dangers

The earlier discussion of Thule and Inuit people presents a picture of extraordinarily competent people moving into the region with confidence and swiftly becoming a dominant force. Inuit were not simply concerned with the physical environment around them, however. Spiritual matters were ever present in their minds (see, for instance Burch 1971; Laugrand, Ooosten, and Trudel 2002; Taylor 1997). Given the importance of spiritual matters, an admittedly speculative discussion of what might have been the Inuit’s spiritual response to Labrador forests follows in hopes of broadening and advancing our understanding of Inuit adaptations to the region.

Among the characteristics of Labrador mentioned only briefly at the beginning of the chapter is its boreal forest. The treeline is currently at Napaktok, where dense stands of spruce abound and stands of larch trees can also be found. There are areas of alder, sedge, and willow brush here and in protected areas further north as well. The presence of dense forests must have both excited the Inuit and given them pause. The excitement would have stemmed from the realization that they now had access to growing trees; they would no longer have to rely solely on driftwood as did Inuit in Baffin Island and other northern regions (Laeyendecker 1993; also see Alix 2005 for discussion of reliance on driftwood in other parts of the Arctic). People could now carefully select specific trees or branches to harvest in order to build boats, sleds, dwellings, and other structures, and to make weapons and implements. For instance, they could cut down a larch tree, whose timber was relatively free of knots, and make robust sled runners; they could select strong and resilient wood to make into sinew-backed bows (Turner 2001, 241, and 246) or cut individual branches that would yield straight grained wood from which to fashion arrow shafts.

Where did trees fit into Inuit ideology? Lucien Turner collected two different accounts concerning the place of trees in the chain of beings in Ungava Bay Inuit origin myths. In one case trees are the source of all animals. According to the account, “a man who was cutting down a tree observed that the chips continued in motion as they fell from the blows. Those that fell into the water became the inhabitants of the water. Those that fell on the land became the various animals and in time were made the food of mankind” (Turner 2001, 261). In the other account, trees and other vegetation have a maritime origin, as they are associated with seaweed (261). In these accounts, trees have a beneficial and benign association. It would be worth reviewing accounts collected by Moravian missionaries and other travellers to help understand the place of trees in the ideology of Labrador Inuit.

The excitement generated by standing trees might have been tempered by some trepidation about forests. The terrain of densely packed trees and brush that Inuit would have encountered as they proceeded south of Napaktok would have been difficult to walk through. In addition, the expansive vistas and unhampered views, so typical of the tundra and so familiar to Inuit, would have been replaced by a landscape that must have seemed rather claustrophobic. The forests were also home to many forms of life with which the Inuit would not have been familiar and about which they would have had no oral history or mythology to guide them. Small creatures, including spiders, beetles, flies, bees, moths, and worms, might have been of particular concern, judging from ethnographic studies of Inuit from other parts of the Arctic. For instance, among Baffin Inuit, these small creatures were known as qupirriut (Laugrand and Oosten 2010). Among many Inuit across the Arctic, qupirriut were seen as spiritually powerful, their larvae and adult phases evoking transformation imagery. While some could be helping spirits, many were deemed dangerous (Burch 1971; Laugrand and Oosten 2010). The diversity and quantity of such creatures in the boreal forest must have been quite unsettling. According to Frédéric Laugrand (2009, pers. comm.), Inuit in Baffin often associated large numbers of creatures, such as swarms of mosquitoes or herds of caribou, with the concept qupirriuk. Did the Labrador Inuit associate the sheer number of trees in large stands of forest with that concept as well?

There is another reason to think that the forested areas, if not the trees themselves, were associated with spiritual dangers. Bjarne Grønnow (Grønnow 2009) explains that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century West Greenland Inuit who were living in coastal areas ventured into interior regions near the Ice Cap with extreme caution. They believed this unfamiliar interior region was populated by dangerous supernatural beings in the forms of human outcasts, ghosts, giants, and monstrous animals and insects. Inuit travelled to the interior and camped there when pursuing caribou, but they were always mindful of the dangers that lurked on that landscape. Like the interior of Greenland, the forested areas of Labrador might have been places to go to in search of resources, but not to linger in for prolonged periods of time. Further south, the association of forested regions with Point Revenge and later Innu might have only increased Inuit’s unease about forested regions and the dangers lurking in them.

If these suggestions have merit, it is possible to begin to consider some of the settlement choices pioneering Inuit and subsequent populations made in a new light. The original settlement of far outer islands and other extreme coastal locations would have made spiritual as well as economic sense. Inuit would have moved onto landscapes in which they were spiritually comfortable, keeping forested areas at a distance. The move to central places in the eighteenth century would have made economic and ecological sense, but probably would have caused the Inuit some spiritual distress because the move would have placed them in close proximity to, if not within, forested areas.

In this context, the harvesting of large numbers of trees around Uivak, Oakes Bay, and other eighteenth-century sites south of the treeline might have made practical as well as spiritual sense. As noted earlier, the trees would have been cut down to make way for sod houses and the timber utilized in house construction, while the boughs of downed trees would have been used to appoint the homes. Additionally, Inuit might have been motivated to harvest large numbers of trees because of a need to push the forests away from habitations, thereby eliminating the claustrophobic sense generated by the forested landscape, as well as creating distance between Inuit families and the spiritual dangers associated with the forest. Labrador Inuit might have been actively domesticating the landscape around their homes, transforming the unfamiliar and therefore dangerous forested lands into familiar, open tundra expanses. The spiritual beings associated with the tundra would have been well known, the systems of coping with or mediating its hazards well understood. The Labrador Inuit newcomers might have been reacting to Labrador’s forest cover in much the way that pioneering families in western United States and Canada reacted to dense growth there. The western pioneers cleared and fenced land for ranching and farming, but also to keep the wilderness, with all its real and perceived dangerous associations, away from their homesteads.

Summary

Surveys and excavations of northern and central Labrador Inuit sites have provided a broad picture of how Inuit economically adapted to those sections of the coast and responded to changes in their natural and social environment. An in-depth examination of an eighteenth-century sod house has provided a more detailed picture of an Inuit household’s extensive use of both marine and terrestrial resources. In particular, Inuit use of plants to build and furnish their homes, as well as to provide additional sources of food, became evident in the analysis. These examinations of Inuit life on two different scales reveal that Inuit maintained flexibility and used considerable ingenuity when dealing with changes to their world.

A consideration of how the Inuit responded to a new resource—living trees—and an unfamiliar environment—the forest—indicates yet another way Labrador Inuit adjusted to life in a land that proved challenging in both the physical and spiritual sense. The chapter suggests that initially Labrador Inuit appear to have taken care to avoid spiritual dangers associated with the forest by settling on familiar landscapes at some distance from that claustrophobic, unfamiliar environment. When economic circumstances led the eighteenth-century Inuit to relocate sod house settlements close to or within forested areas, people appear to have continued to adapt. They cut down forests around their sod house settlements, creating landscapes that exhibited familiar physical and spiritual characteristics. In dealing with spiritual concerns, as well as environmental and social challenges, the Labrador Inuit exhibited much resourcefulness and ingenuity.

Acknowledgements

The research discussed here could not have been accomplished without the collaboration of Jim Woollett. I also want to thank Brendan Buckley, Rosanne D’Arrigo, Allison Bain, and Cynthia Zutter for their efforts on behalf of this project, and the many crews of students for their careful work in the field. I am also grateful to Henry Webb and The Torngâsok Cultural Centre for logistical assistance over many years. I also want to thank Claire Alix for her comments on the character of the Uivak wood, and Frédéric Laugrand for his thoughtful observations about trees. Grants from the Office of Polar Program, National Science Foundation, awarded to Susan A. Kaplan (OPP-9307845 and OPP-9615812) and Jim Woollett (OPP-9616802), supported the bulk of the fieldwork reported here. Bowdoin College and Kane Lodge Foundation, Inc. provided additional support. Permission to conduct the research was provided by The Torngâsuk Cultural Centre and the Provincial Archaeology Office, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Newfoundland-Labrador. All figures and photos by Susan A. Kaplan.

References

Alix, Claire. 2005. “Deciphering the Impact of Change on the Driftwood Cycle. Contribution to the Study of Human Use of Wood in the Arctic.” Global and Planetary Change 47: 83–98.

Bain, Allison. 2000. “Uivak Archaeoentomological Analysis 2.” Report on file in the office of Susan A. Kaplan, Bowdoin College.

Banfield, A.W.F. 1974. The Mammals of Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Barkham, Selma. 1977. “Guipuzcoan Shipping in 1571 with Particular Reference to the Decline of the Transatlantic Fishing Industry.” In Anglo-American Contributions to Basque Studies: Essays in Honor of Jon Bilbao, edited by William A. Douglass, Richard W. Etulain, and William H. Jacobsen, Jr., 73–81. Publications on the Social Sciences No. 13. Reno: Desert Research Institute.

_____. 1978. “The Basques: Filling a Gap in our History between Jacques Cartier and Champlain.” Canadian Geographical Journal 49, 1: 8–19.

_____. 1980. “A Note on the Strait of Belle Isle during the Period of Basque Contact with Indians and Inuit.” Études/Inuit/Studies 4, 1–2: 51–58.

Bird, Junius B. 1945. Archaeology of the Hopedale Area, Labrador. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 39, 2. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

Bodenhorn, Barbara. 1990. “I’m Not a Great Hunter, My Wife Is: Iñupiat and Anthropological Models of Gender.” Études/Inuit/Studies 14, 1–2: 55–74.

Boles, Bruce. 1980. Offshore Labrador Biological Studies, 1979: Seals. St John’s: Atlantic Biological Services.

Brewster, Natalie. 2008. “The Archaeology of Snack Cove 1 and Snack Cove 3.” North Atlantic Archaeology 1: 25–42.

Brice-Bennett, Carol. 1981. “Two Opinions: Inuit and Moravian Missionaries in Labrador 1804–1860.” MA thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Briggs, Jean. 1970. Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Burch, Ernest S. 1971. “The Nonempirical Environment of the Arctic Alaskan Eskimos.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 27, 2: 148–65.

Cox, Steven. 1977. “Prehistoric Settlement and Culture Change at Okak, Labrador.” PhD diss., Harvard University.

Dahl, Jens. 2000. Saqqaq: An Inuit Hunting Community in the Modern World. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

D’Arrigo, Rosanne, Brendan Buckley, Susan A. Kaplan, and Jim Woollett. 2003. “Interannual to Multidecadal Modes of Labrador Climate Variability Inferred from Tree Rings.” Climate Dynamics 20: 219–28.

Fitzhugh, William. 1978. “Winter Cove 4 and the Point Revenge Occupation of the Central Labrador Coast.” Arctic Anthropology 15, 2: 146–74.

_____. 1994. “Staffe Island 1 and the Northern Labrador Dorset-Thule Succession.” In Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., edited by David Morrison and Jean-Luc Pilon, 239–69. Hull: Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Grønnow, Bjarne. 2009. “Blessings and Horrors of the Interior: Ethno-historical Studies of Inuit Perceptions Concerning the Inland Region of West Greenland.” Arctic Anthropology 46, 1–2: 191–201.

Hawkes, E.W. 1970 [1916]. The Labrador Eskimo. Canadian Department of Mines, Geological Survey Memoir 91, Anthropological Series No. 14. Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau.

Jordan, Richard H. 1978. “Archaeological Investigations of the Hamilton Inlet Labrador Eskimo: Social and Economic Responses to European Contact.” Arctic Anthropology 15, 2: 175–85.

Jordan, Richard H. and Susan A. Kaplan. 1980. “An Archaeological View of the Inuit/European Contact Period in Central Labrador.” Études/Inuit/Studies 4, 1–2: 35–45.

Kaplan, Susan A. 1983. “Economic and Social Change in Labrador Neo-Eskimo Culture.” PhD diss., Bryn Mawr College.

_____. 1985. “European Goods and Socio-economic Change in Early Labrador Inuit Society.” In Cultures in Contact: The European Impact on Native Cultural Institutions in Eastern North America, A.D. 1000–1800, edited by W.W. Fitzhugh, 45–70. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

_____. 2009. “From Forested Bays to Tundra Covered Passes: Transformation of the Labrador Landscape.” In On Track of the Thule Culture from Bering Strait to East Greenland, edited by Bjarne Grønnow, 119–28. Studies in Archaeology and History, Vol. 15. Copenhagen: National Museum.

Kaplan, Susan A., and James M. Woollett. 2000. “Challenges and Choices: Exploring the Interplay between Climate, History, and Culture on Canada’s Labrador Coast.” Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 32, 3: 351–59.

Laeyendecker, Dosia. 1993. “Analysis of Wood and Charcoal Samples from Inuit Sites in Frobisher Bay.” In The Meta Incognita Project, edited by S. Alsford, 199–210. Contributions to Field Studies, Vol. 6. Gatineau, QC: Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Laugrand, Frédéric, and Jarich Oosten. 2010. “Qupirruit: Insects and Worms in Inuit Traditions.” Arctic Anthropology 47, 1: 1–21.

Laugrand, Frédéric, Jarich Oosten, and François Trudel. 2002. “Hunters, Owners, and Givers of Light: The Tuurngait of South Baffin Island.” Arctic Anthropology 39, 1–2: 27–50.

Logan, Judith A., and James A. Tuck. 1990. “A Sixteenth Century Basque Whaling Port in Southern Labrador.” Association for Preservation Technology International, Bulletin 22, 3: 65–72.

Loring, Stephen. 1992. “Princes and Princesses of Ragged Fame: Innu (Naskapi) Archaeology and Ethnohistory in Labrador.” PhD diss., University of Massachusetts.

Loring, Stephen, and Beatrix Arendt. 2009. “‘…they gave Hebron, the city of refuge…’ (Joshua 21:13): An Archaeological Reconnaissance at Hebron, Labrador.” Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1: 33–56.

Loring, Stephen, and Melanie Cabak. 2000. “A Set of Very Fair Cups and Saucers: Stamped Ceramics as an Example of Inuit Incorporation.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 4, 1: 34–52.

Loring, Stephen, and Leah Rosenmeier, eds. 2005. Angutiup Ânguanga/Anguti’s Amulet. Central Coast of Labrador Archaeology Partnership. Truro, NS: Eastern Woodland Publishing, Millbrook First Nation.

McLaren, Ian A. 1958. The Biology of the Ringed Seal (Phoca hispida schreber) in the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Bulletin 118. Ottawa: Fisheries Research Board of Canada.

Payette, S., L. Filon, L. Gauthier, and Y. Boutin. 1985. “Secular Climate Change in Old-growth Tree-line Vegetation of Northern Quebec.” Nature 315: 135–38.

Pinhorn, A.T. 1976. Living Marine Resources of Newfoundland-Labrador: Status and Potential. Fisheries Research Board of Canada Bulletin 194. Ottawa: Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service.

Romero, Aldemaro, and Shelly Kannada. 2006. “Comment on ‘genetic analysis of 16th-century whale bones prompts a revision of the impact of Basque whaling on right and bowhead whales in the western north Atlantic.’” Canadian Journal of Zoology 84: 1059–65.

Savelle, James M., and Junko Habu. 2004. “A Processual Investigation of a Thule Whale Bone House: Somerset Island, Arctic Canada.” Arctic Anthropology 41, 2: 204–21.

Schwartz, Fred. 1977. “Land Use in the Makkovik Region.” In Our Footprints Are Everywhere: Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in Labrador, edited by Carol Brice-Bennett, 239–78. Nain: Labrador Inuit Association.

Stopp, Marianne P. 2002. “Reconsidering Inuit Presence in Southern Labrador.” Études/Inuit/Studies 26, 2: 71–108.

Taylor, J. Garth. 1974. Labrador Eskimo Settlements of the Early Contact Period. National Museums of Canada Publications in Ethnology, 9. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada.

_____. 1988. “Labrador Inuit Whale Use during the Early Contact Period.” Arctic Anthropology 25, 1: 120–30.

_____. 1997. “Deconstructing Deities: Tuurngatsuak and Tuurngaatsuk in Labrador Inuit Religion.” Études/Inuit/Studies 21, 1–2: 141–53.

Taylor, J. Garth, and Helge Taylor. 1977. “Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in the Okak Region, 1776–1830.” In Our Footprints Are Everywhere: Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in Labrador, edited by Carol Brice-Bennett, 59–82. Nain: Labrador Inuit Association.

Trudel, François. 1980. “Les relations entre les Français et les Inuit au Labrador Méridional, 1660–1760.” Études/Inuit/Studies 4, 1–2: 135–45.

Turner, Lucien M. 2001. [1894] Ethnology of the Ungava District, Hudson Bay Territory. Eleventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology. Reissued as part of Classics of Smithsonian Anthropology Series. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Whiteley, W.H. 1964. “The Establishment of the Moravian Mission in Labrador and British Policy 1763–83.” Canadian Historical Review 45, 1: 29–50.

Woollett, James M. 2003. “An Historical Ecology of Labrador Inuit Culture Change.” PhD diss., City University of New York.

_____. 2007. “Labrador Inuit Subsistence in the Context of Environmental Change: An Initial Landscape History Perspective.” American Anthropologist 109, 1: 69–84.

Zutter, Cynthia. 2000. “Archaeobotanical Investigations of the Uivak Archaeological Site, Labrador, Canada.” Report on file in the office of Susan A. Kaplan, Bowdoin College.

_____. 2009. “Paleoethnobotanical Contributions to 18th-century Inuit Economy: An Example from Uivak, Labrador.” Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1: 23–32.