The various political shifts and upheavals within the communist world all have one thing in common: the undying urge to create a genuine civil society.

—Václav Havel, 19881

WHILE DISPATCHING CONSULTANTS ACROSS THE OCEAN as its agents of change, the West also set out to supplant communism by supporting certain local organizations and groups as exemplars of and vehicles for creating democracy and a civil society. This approach held that, under communism, the nations of the Eastern Bloc never had a “civil society,” in which citizens and groups were free to form organizations that functioned independently of the state and that mediated between citizens and the state.

Because this lacuna epitomized the all-pervasive communist state, both Western and Central European opinion makers saw creating a civil society and independent organizations as building the connective tissue of a new democratic political culture. The experience and writings of Central European dissident intellectuals such as Václav Havel in Czechoslovakia and Adam Michnik in Poland helped crystallize the view of an idealized civil society2 playing a vital reconstructive role in the former communist states. Although the concept subsequently became central to how donors thought about Central and Eastern European “transition,” in the recipient societies, the idea tended to be limited to certain circles. It was not, for example, necessarily shared by large segments of the various populations (not even by parts of the Opposition close to Poland’s Roman Catholic Church).

The building blocks of civil society were thought to be nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), which donors also saw as important vehicles of technical assistance and training. Donors had high hopes for this “independent sector”: It was to replace the discredited centralized bureaucratic state, decentralize services, and build democracy. And so donors made the development of a civil society and support of NGOs a primary focus, if not always as a funding priority, certainly in rhetoric.

Americans tended to talk the loudest about establishing civil societies in the region.3 The fall of the Berlin Wall energized American efforts to try to remake Central and Eastern Europe in “our” image by exporting the can-do mentality and the tradition of citizens’ initiatives and local governance. The U.S. Congress obligated some $32 million in 1990-91 to support “democratic institution building” in Poland and the other ex-communist states.4 By the end of 1999, the United States had obligated $379 million to promote political party development, independent media, governance, and recipient NGOs.5 Many of these projects were carried out through grants to American quasi-private organizations, notably the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and its affiliated institutes, including the AFL-CIO’s Free Trade Union Institute (FTUI), the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), and the National Democratic and National Republican Institutes for International Affairs (NDI and NRI). A host of American NGOs, seasoned by USAID- and foundation-supported work in the Third World, also lobbied and competed with each other for the new business.

While bilateral donors such as the United States provided grants directly to NGOs in the region (albeit often using Western NGOs as their intermediaries), the EU’s PHARE program worked through agreements negotiated with the governments and coordination units of the host countries. (In both cases, though, government bureaucracies provided relatively little oversight.) Two main initiatives in Central Europe have emerged from the PHARE program since 1991: “social dialogue” and “civil society.” Social dialogue activities were designed to bolster NGOs in the region by providing information, legal services, training, and grants for projects, while under the civil society program, PHARE has supported locally administered NGOs with funds (typically totaling between 100,000 to 200,000 ECU, roughly $119,000 to $261,0006) administered through the EU delegations in the region. In addition to these initiatives, PHARE has financed NGOs working in social welfare areas through grants administered by the labor ministries in Hungary and Poland as well as financed cooperation and exchange between higher education institutions in nations of the European Union and those of Central Europe.7 By the beginning of 1998, the EU’s PHARE program had contributed nearly 158 million ECU (roughly $194 million8) to support civil society, including NGOs and democracy development in Central and Eastern Europe.9

Yet despite lip service to democracy building throughout the aid effort, as of 1999, the United States had devoted only about 17 percent of its Central and Eastern European aid expenditures to democracy assistance.10 With regard to Russia, the share of democracy assistance was approximately two percent as of 1999.11 Similarly, the EU’s democracy program to Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union comprised only about one percent of its assistance budget.12

Private donors made an equal—if not greater—contribution to democracy assistance than governments. The collapse of communism galvanized more than 60 European and North American foundations, most of which had not previously been active internationally.13 The Hungarian American financier George Soros, who began philanthropic involvement in the region before 1989, undertook a huge effort. The “Soros network,” as it is sometimes called by insiders, consists of country-specific foundations, network programs, and short-term initiatives.14 Soros has spent more in the region than any other foundation and some bilateral donors.15

But, as with privatization efforts, it would be difficult, if not impossible, for any donor—public or private—to create democratic pluralism from the outside. As anthropologist Steven Sampson has observed, “NGOs in Eastern Europe are unique in that they are specific products of the communist and postcommunist political cultures, on the one hand, while being overtly influenced—if not totally financed—by foreign actors on the other.”16 Foreign financing in the form of grants meant that choices had to be made about just who the appropriate grantees were. Donors were profoundly ill equipped to make these choices. They were easily outdone by Central and Eastern Europeans skilled in the necessary arts of self-presentation and preservation through their experiences under communism.

Just who were these brokers? In Poland and Hungary, many were members of long-standing elite groups who had survived by asserting themselves against a stifling state. Where the state had tolerated pockets of “independent activity” beyond its control, tight-knit groups formed “small circles of freedom” and even pushed the limits of state tolerance in both economic and political arenas. Before 1989 in Poland, for example, many Solidarity activists had redefined reform by redirecting their efforts from political to economic activity and preaching a new philosophy: form a club or lobby to do what needs doing and finance it through entrepreneurial activities. Some people who had previously exchanged underground leaflets at private gatherings turned to trading software and financial schemes. These small circles provided identity, intimacy, trust, and pooled resources, all vital for both political and economic sustenance. Much Western assistance to Central Europe after 1989 was built on the backbone of these energized elites; they cultivated international contacts and set up NGOs and “foundations” to receive Western funds.17 In addition to these established groups, a new class of economically active young adults came into their own in the 1990s. Although, as individuals, some played brokerage roles, they generally were not major beneficiaries of Western aid.

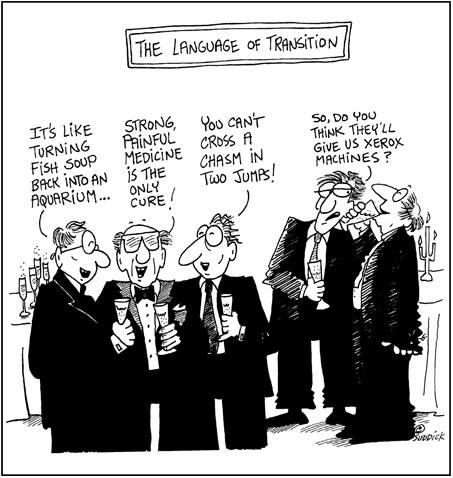

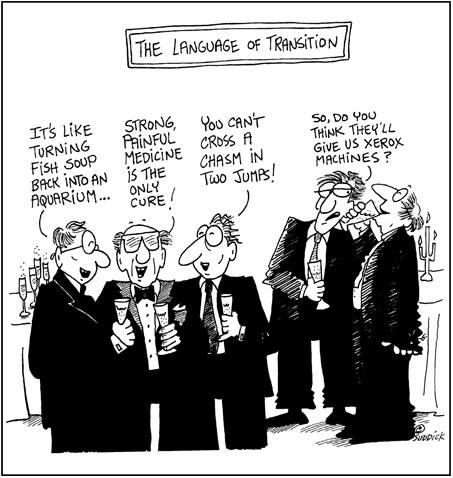

If a few groups had built their base on oases of “independent activity,” and younger participants were forging new ground, others in the region had survived and thrived by planting themselves firmly within the Communist Party apparatus and state. Many visible new businessmen were former nomenklatura operatives; some also set up “foundations.” Further east, in Russia and Ukraine, many intermediaries favored by the West were former communists. As anthropologist Sampson has described, many of these people in the recipient countries learned very quickly how to manipulate and maneuver the new orbit of opportunities:

One sign of the transition is that some individuals who were very good at the “wooden language” of socialism have now mastered the jargon of democracy programmes, project management, capacity building and other catch-phrases such as “transparency” and “empowerment.” Such individuals serve as brokers in the unequal relationship between the west and the east. Like brokers everywhere, they manipulate resources and thrive off the maintenance of barriers. The forum for such activity is the world of projects, and civil society development is part of this world.18

The established groups, regardless of their role under communism, served as gatekeepers for aid from the West. They had carte blanche to put their irons into all fires simultaneously—policy, government, business, politics, and foundations. And so a handful of brokers made decisions and amassed resources on a large scale, by local standards, and Western funding tended to reinforce their success.

The trouble with this is that the choices the donors made were inevitably problematic, especially given one powerful and persistent communist legacy: the pivotal role of the state and its strong, centralized bureaucracy.19 After the collapse of communism, the agendas of the donors and the new leaders of Central and Eastern Europe came together: The donors could secure the demise of the discredited communists and fill the postcommunist power vacuum where it existed;20 the leaders could leverage the aid to consolidate their positions, just as the communists had controlled state resources. This confluence helped to create a paradoxical path for aid to take: The central role of the state under communism smoothed the way for the donors by providing a model that persisted beyond its collapse. And so demons from the past came to haunt aid programs intended to help establish democracy and civil society, just as they had privatization.

AGENDAS IN COMMUNISM’S AFTERMATH

During the period of euphoria and excitement immediately following the collapse of communism, local access to the West was the way to get ahead. One of the many places this could be seen in the spring of 1990 in the newly independent Poland was at the Polish Council of Ministers, a cabinet-level office. There, dozens of Poles were attending a “training for democracy” workshop set up for the leaders of the region’s new political parties and put on by visiting American political consultants and media pollsters.

Aleksander Hall, the minister responsible for political parties, opened the workshop. Soft-spoken and looking uncomfortable in a suit with trousers hanging over the tops of his shoes, he welcomed the guests. The leaders of the “political parties” graciously, deferentially, and profusely thanked the Westerners for coming to teach democracy. “We have so much to learn from you,” said one. The consultants were equally elated to meet the maiden leaders of Poland. The leaders of so many political parties—35—had taken the time to attend the workshop. What a coup! The consultants exulted over the death of communism and said how grateful they were to have this rare opportunity to assist Poland. Listening dutifully, the Poles were treated to an explanation of the importance of fliers and mass mailings in a session entitled “How to Use the Post Office in a Political Campaign”—in a country where one of the greatest political landslides in its history had just been accomplished without the post office, which was notorious for taking days to deliver a letter across town or for simply losing it.

Over three days, the consultants did not learn that candidate-to-citizen meetings in parishes—not glitzy mailings or television ads—had mobilized Polish voters. Moreover, the consultants had little idea whom they were encountering as participants. Yes, they were representatives of “political parties.” For the most part, however, these were not national political leaders but, rather, representatives of political discussion clubs that had mushroomed during the relaxation of control preceding the collapse of communism. The truly influential politicians belonged to citizens’ organizations that claimed to represent the collective interests of all society, not those of politicians, who were seen as selfishly competitive. Minister Hall, one of the few real political players present, represented a long-standing, highly influential Christian democratic group, but it was not a political party at the time.

Why did the Poles care to participate in the workshop? It seemed clear that they hardly expected to glean lessons in democracy from the Americans, who could only tell them about curiosities far removed from Polish political or daily realities. The hallway conversations, especially their unspoken subtexts, exposed the gap between the foreigners—enthusiastic, well intentioned, and naive—and the quick-on-the-uptake Poles, who parroted the buzzwords of pluralism and civil society while pursuing the main goal of each of them: access to potentially useful foreigners. The Poles painted a grim picture of their circumstances, one that played to the Westerners’ inflated view of their own usefulness.

A consultant (respectfully): “You were in prison, too? I admire your courage.”

A politician (smiling modestly): “Yes, I was.” [It didn’t take any special courage. I was picked up just like all my friends.]

A consultant: “You suffered. If there’s anything we can help you with now, just let us know.”

A politician: “The workshop has been so enlightening. One thing just occurred to me. There’s a shortage of paper and, you know, we don’t have enough money to buy fax or photocopy machines.” [Of course, we think you can help. Travel abroad? Funds? Other contacts? Anything that might give us visibility in the West and the prestige we need here that is associated with Western exposure. That’s why we bothered to come to your workshop.]

A consultant: “Perhaps my organization could help.”

A politician (humbly): “Oh, we would be most grateful!”

These encounters resembled the rituals observed under communism that had served to cushion foreigners from the real (Polish) world, which foreigners could never quite grasp because they were shielded from harsh realities. Urban Poles, especially those who came into contact with foreigners, tended to talk about things they thought foreigners respected and omitted more dubious topics, such as the wheeling and dealing nearly everyone engaged in to survive. So visitors usually did not learn how Poles obtained goods and services in a shortage economy at a time (1982 and 1983) when the rationing system allowed each citizen one pair of Polish-made shoes per year. Polish formality and reserve arose partially from an instinct to survive in a climate of fear and uncertainty. The rituals and language of public life helped to maintain a mantle of normalcy that enshrouded informal dealings and private life. In its ritual character, public life provided a stark contrast to what many people did unofficially.21 The practice of putting on public shows, honed under communism, was thus ideal preparation for handling the onslaught of people from the West. In an article entitled “Playing the Co-Operation Game,” anthropologist Marta Bruno concludes that “As long as recipients see these occasions [workshops with Western consultants] as a ritual lip-service or as ‘tax,’ which they have to pay in order to obtain funding, they will simply reinforce the artificiality of development projects.”22

The artificiality could be observed on both sides. Oblivious, having had a wonderful time, and having acquired many new “friends,” the consultants moved on to their next workshop in Prague or Budapest. Then they returned home from the whirlwind trip with their misconceptions intact and a stack of makeshift visiting cards. The trip would make good cocktail party conversation for some time; the consultants had made “friends” with the new leaders of Central Europe and helped them to build democracy.

Dozens of such early East-West encounters played out in Warsaw, Prague, and Budapest, and later, when aid resources moved east, in Moscow and Kiev. Deficient in cultural and historical sensibilities, consultants and aid representatives often made social fools of themselves, failing to realize that their chief source of attractiveness was in their own pocketbooks or their perceived access to others’ pockets. Meanwhile, Central and Eastern Europeans—their eyes on foreign travel and access—applied to unsuspecting foreigners the persistence and sophisticated wheeling-and-dealing-skills that they had honed under communism.

A class of resourceful brokers and operators with enough energy and skill to play in the new arena was formed. Central and Eastern European businessmen needed trading partners; academic deans of depleted universities, money to make payroll and foreign trips; physicians, modern equipment and foreign trips. Westerners’ visits to the region, their enthusiasm, and their money provided incentives for local people to formalize existing associations and even to create new initiatives that could attract and receive Western money. As anthropologist Sampson has observed, “Social networks can’t get grants, but autonomous associations can.”23

“Foundations” multiplied: Westerners living in the region were inundated with requests from local friends who had set up organizations and needed help writing English-language proposals to potential funders. One person created a foundation to preserve crumbling monuments, another started one to clean up the polluted environment, and yet another launched a foundation to open a school. As more and more aid money poured in, initiating a project without a Western sponsor became almost unthinkable, like running for public office in the United States after filing for bankruptcy.

The issue was not just money. The issue was, critically, “symbolic capital”—an individual’s combined cultural, social, and financial power, which served to compound the power of the individual’s group in the public arena24—that could be leveraged both in and outside the region. To get money from the West was to be blessed by it, especially in the initial period of East-West contact in each country. Securing Western—sometimes specifically American—funds greatly enhanced one’s reputation and lent legitimacy that could be leveraged internally to enhance symbolic capital and accrue further political, financial, and social rewards. For this reason, even small sums of hard currency could be enormously life enhancing to the beneficiaries.

Just how did partners find each other? The ad hoc atmosphere of the early days of the aid effort was custom made for the class of well-heeled brokers that arose to take advantage of opportunities and to guide foreign partners. Having just come from a power lunch in Paris, the jet-setting American CEO in Prague needed local fixers not only to set up contacts and translate, but also to explain the ABCs of doing business in the new frontier: “Economist,” “bank,” “profit,” “tomorrow,” and “yes” didn’t necessarily mean the same things as in the West. Western foundation representatives, too, needed translators, fixers, and, for the larger operations, local office staff.

The promise of Western money and access often inspired secrecy, suspicion, and competition among groups. The arrival of government and foundation delegations from the West was greeted with bursts of gossip and speculation about who was meeting with whom and who was doing and getting what. Each group developed—and guarded—its own prized Western contacts. It was not necessarily in a group’s interest to share information and contacts with the outside world.

In fact, information about who was who was the most valuable—and scarcest—commodity on the East-West circuit, especially during the Triumphalist phase. Westerners were entering a previously semiclosed world, usually not knowing much, if anything, of its sophisticated legacy of reputations, cliques, and intrigue. Representatives of foundations, corporations, and government agencies typically toured the region with lists of up to a dozen or so names of the “most important people” for each country. Names often were obtained from other Westerners and by virtue of Easterners’ visibility in the West. The lists became self-fulfilling prophecies; many of those whose names appeared on them in time received funding from multiple sources.

Thus, although a multitude of Western programs offered travel, training, and scholarship opportunities, there were only a few channels of selection for them. There was much to be done, but seemingly few to do it: Only a few highly skilled Easterners were adept at working in the new environment. The same groups and individuals, who tended to travel in the same circles as each other, took advantage of multiple opportunities.

Easterners, too, often had little information about Western personalities and organizations, but were quick studies in maneuvering the situation to their advantage. Many educated and astute young adults from intelligentsia backgrounds carved out a triad of business, foundation, and scholarly activities. Western partnerships facilitated all of these activities, and so such Easterners also served as consultants, brokers, and partners, and depended more on Western contacts and opportunities than on indigenous ones. Previously engaged in traditional academic careers in philosophy, philology, and physics that commanded respect, but little income, they now were involved in both the old activities that afforded the intelligentsia prestige and the new ones that offered money. Many members of Poland’s bright young intelligentsia split their energies between lucrative business activities and sociology (a catch-all field under which critical discussion had been possible in communist Poland and Hungary and in which many who assumed important positions in postcommunist Central Europe had been trained). Many assistant professors of sociology and psychology set up businesses and/or foundations “on the side,” all the while carrying out minimal duties at the university and collecting meager state salaries.

One such person was Grzegorz “Larry” Lindenberg, a Ph.D. sociologist in his early 30s. Lindenberg was short, slight, friendly, and, in contrast to his Western counterparts, casually dressed and often smiling behind a bushy beard. Poor after their release from martial-law internment, he and a few of his ex-cellmates had in time begun to trade in computers and electronic equipment by traveling from Singapore to Bratislava to Warsaw and Kiev. In addition, Lindenberg became the managing editor of the newly created Gazeta Wyborcza, which quickly became the most widely circulated newspaper in Poland. Using his access throughout Poland—starting with the Ministries of Industry and Finance—Lindenberg helped some Western investors navigate the country’s complicated bureaucratic and political structures. He also played a role in promoting Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs when Sachs first appeared in Poland in the late 1980s.

Called upon by their countrymen to be economic and political players and to help their country get back on its feet, new managers such as Lindenberg became windows to the West at a crucial time and served as invaluable assets to Western investors, attorneys, and entrepreneurial academics. As these businessmen received scores of calls and offers from Westerners, their visibility and opportunities quickly compounded. Myriad such contacts blossomed for mutual advantage, as well as to facilitate efforts that would have wider influence.

EARLY EASTERN GATEKEEPERS

Before the revolutions of 1989, important precedents for giving and receiving had been set both by donors and by Central European recipients. Individuals with name recognition in the West—often dissidents—tended to be selected as the beneficiaries of Western help. In their own social contexts, they were “more equal than others.” Some on-the-scene observers contended that endowing them with resources may have reinforced existing social hierarchies. In an article entitled “The Opposition and Money,” a known activist writing under a pseudonym explained the role of Western money in supporting underground operations and the very survival of the Polish Opposition in the late 1970s and 1980s:

It is worthwhile to remember that those who carry out such lofty and noble ends are still human beings like the rest of us, who need money to live.… Payments for articles, books, reviews, and sometimes interviews published in the West provided Oppositionists with much-needed income. Some received awards; others were granted lucrative Western scholarships or fellowships. Activists had many opportunities to earn money at home by working for independent papers and publishing houses (that paid in złoty) or working for Western correspondents (for dollars) as translators or fixers.… Some Oppositionists were more equal than others. Well-known activists had many more opportunities to earn money than their less famous colleagues. Such genuinely eminent figures … could live comfortably from selling their views in the form of paid interviews with foreign press agencies. Indeed, such people had many more offers than they could accept. Western journalists worked for Western editors, who had only a vague idea about the situation in Poland, and thus always demanded the same names. Such Oppositionists often had to turn down intrusive Western correspondents.

Moreover, in such necessarily clandestine circumstances, there was a natural tendency to blur the lines between what was one’s own and what belonged to the group, and thus was meant for wider benefit.

The distinction between monies and goods designated for individual and for collective use was never clear.… Exact bookkeeping was often deemed impossible for security reasons, and the activists’ own money easily got mixed with the “company” money.… It was also rather difficult at times to determine whether an activist was honored with some prize from abroad for his personal, individual achievements or on behalf of the group and the cause he represented. Did, for example, the Nobel Peace Prize simply honor the undoubtedly heroic Lech Wałęsa or also millions of less famous, more deprived, more easily suppressed workers across a defiant nation? In some cases a contributor earmarked the money for a common, opposition purpose, in others he did not. One may presume that the recipient kept some part of it for himself.25

However different the circumstances, the recipients that donors selected and what these recipients did with the money in the thaw years of the 1980s set patterns that persisted into the 1990s. To a large degree, assistance under the rubric of building democracy, civil society, and independent institutions was, especially in the years immediately after 1989, a continuation of the status quo; that is, donors funded the same individuals and groups they had previously supported. For example, through FTUI, NED continued its support, begun in 1984, to Solidarity with a grant of $355,000 in fiscal year 1989 to assist Solidarity activities both in and outside Poland. Through the International Rescue Committee in New York, NED renewed funding, begun in 1987, to Solidarity with a grant of $1 million in fiscal year 1989 to maintain a social services fund to assist workers and their families.26 Through the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences, NED carried on funding that in part supported “independent scholars and writers in Czechoslovakia.”27 NED president Carl Gershman described the endowment’s targets:

Endowment funds were used to provide supplies and equipment for the independent publishing movements in Poland; to sustain independent publications as well as independent cultural, human rights, and political organizations in Czechoslovakia; to provide Hungarian dissidents with paper and ink to publish their journals during the period before the opening; to support regional initiatives and transnational cooperation among democratic movements throughout the region through the Multinational Fund for Friendship and Cooperation in Central and Eastern Europe, a movement of democratic activists themselves; and to provide communications technology and knowledge to the emerging independent publishing and press groups in the Soviet Union.28

In 1989, with the collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, the West affirmed its support of the new noncommunist politicians and leaders who would shape the direction of Central and Eastern European states. The flood tides that had swept away the communist regimes brought unprecedented opportunities—and obligations—into the hands of the heroes of resistance. The communists’ fall from power left a vacuum in many areas of public life, from finance and foreign affairs to health and social services. (Of course, a few years later the communists had reassumed power in Poland and Hungary and also had enriched their roles in the private economy.) And a multitude of new institutions had to be created: financial and regulatory systems, ministries of privatization, and independent news organizations. With the old guard gone overnight, a small group of trusted and untainted new leaders had to staff the old posts and to identify, create, and fill the positions needed to shape the new environment. Western donors were eager to participate in this process and especially to support people who had name recognition as heroes of the revolution.

The U.S.-funded NED already mentioned, which distributed nearly all the SEED money allocated by the U.S. Congress for “democratic institution building” in 1990, was an important case in point. NED supported the new democratic leaders by funding their political parties and groups. Under NED, the NDI and the NRI, as well as the International Foundation for Electoral Systems and other organizations, provided training and assistance to political parties.29

In Hungary, these organizations financed emerging political parties, notably the Alliance of Free Democrats. The support was intended to “help to shape political public opinion in Hungary during this transitional period, through publications, seminars, and lectures on democracy. Communication and interaction among the alliance’s network throughout the country [was] also [to] be strengthened.”30 In Poland, NED financed the Citizens’ Committees—the local and national fora under which most of the pre-1989 opposition organized itself in 1990-1991.31 The Citizens’ Committees were major recipients of U.S. political aid to the opposition in Poland and had at their disposal significant political, diplomatic, and media support, particularly from Radio Free Europe—assistance that proved pivotal.32 And, in Czechoslovakia, NED provided organizational support for the political party Civic Forum,33 which appears to have given it advantages vis-à-vis other groups throughout the Czech and Slovak political spectrum. A number of private funders also provided decisive support to political parties: The New York-based Freedom House, for example, provided direct assistance to political parties in Poland and Hungary, while the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation supplied funding in Czechoslovakia. The national foundations of George Soros generally were directed by his longtime associates and boards made up of former dissidents often involved in political, not only intellectual, pursuits.34

The groups that the West chose to fund in the early 1990s tended to include high-profile activists who had been visible in the West in the 1980s. One such individual was Adam Michnik. Under communism, Michnik was an historian and influential intellectual of a prominent Polish Opposition group. After communism, he was editor-in-chief of Gazeta Wyborcza and, for a short time, an active politician. Long before Solidarity existed, the youthful Michnik jeopardized his freedom to oppose the communist regime. When, in 1980, the entire nation rose up behind Solidarity, he assumed leadership and authority. And 18 months later, when General Wojciech Jaruzelski imposed martial law and outlawed Solidarity, Michnik sat in a prison cell. He wrote essays for the New York Review of Books that conveyed both the mean atmosphere of Poland under martial law and its undaunted spirit of hope and resistance.

Now, with communism fallen, Poland seemed like a blank slate. Michnik became involved in innumerable activities to put his country on a democratic course: Having helped select the leaders of Central Europe’s first noncommunist parliament, he sat in the Polish Sejm and served as a leader of the powerful political movement Citizens’ Movement for Democratic Action (ROAD), which had been started by the faction of Solidarity that grew out of the non-nationalist wing of the Opposition. Michnik was also an effective fundraiser and proved himself as an organizer not only of political action, but of institutions that had inescapably economic aspects, such as his newspaper.

Revered by Western intellectuals, Michnik met with dozens of visitors. In the early years of transformation, he became the darling of many Western foundations. Many resources went to support the projects of people in his circle. Gazeta Wyborcza, the first independent daily in Central and Eastern Europe, received grants from a number of Western sources, including a grant of $55,000 in 1989 from the U.S. government (through NED and the Polish American Congress Charitable Foundation).35 Such sums went a very long way in Poland at the time.

Despite Michnik’s talents and image in the West, not all of his countrymen were so admiring and impressed. At the same time he was writing essays celebrated in the West, some Polish critics said that he and those like him were building their careers on their reputations in and sponsorship from the West, and that the extensive contacts and support over the years gave them unfair advantages. Politicians outside what they perceived as the favored group, such as Piotr Wiśniewski of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS), a leftist party, were unhappy with this state of affairs. And Zbigniew Rykowski, associated with an opposing right-wing political group, characterized the Soros-created Stefan Batory Foundation as a “headquarters for ROAD.”36 Indeed, the Batory Foundation’s board members were, for the most part, from the same circle and associated with business enterprises. As insider Irena Lasota herself acknowledged: “Let us not kid ourselves. Batory operates like a political party. It may be a very nice political party, with which many of us agree, but it is a political party nonetheless.”37 However, many of the critics of this circle were themselves vying for Western support.

The fact that NED financed selected political groups to the exclusion of others fed perceptions among some groups that the United States was playing partisan politics. In Poland’s parliamentary election of 1991, for example, NED funded only the incumbent candidates, who already had an advantage because they had almost exclusive access to the government-owned television, radio, and press.38 The political opposition was displeased with this. Vocal disagreement came from the ranks of the Confederacy of Independent Poland (KPN), the populist, nationalist, and traditionalist group that had participated in the formation of Solidarity and maintained some support from young workers, students, and small private businessmen. As a result of this and other funding decisions, KPN sent a spokesman to testify before a U.S. congressional subcommittee in March 1990. In statements submitted in subcommittee hearings, KPN charged that:

The idea to support democracy and pluralism is a very good one. But that has nothing to do with using NED funds to bolster leftist groups in Poland while the center and center-right groups receive no funds at all.39

A KPN spokesman further complained:

The groups that emerged from the Communist Party and its allies and Solidarity have enormous resources and maintain an almost complete monopoly in the media while independent political parties that enjoy increasing popular support are denied resources or equal access to the media.… Leaving all the American assistance in the hand of one political orientation is not acceptable. It is as if in the United States all finances for political campaigns were given only to the Democratic Party, which would allocate or promise to allocate some money for the Republican Party.40

The pattern of providing funding to explicitly political parties and groups continued farther east. Between 1992 and 1997, USAID awarded NDI and NRI a combined sum of $17.4 million to conduct programs in Russia. From 1990 to 1992, these organizations used about $956,000 in NED funds to help the anticommunist Democratic Russia Movement establish a printing facility and disseminate literature. NDI and NRI also conducted civic education and grassroots organizing programs for Russians at the national and local levels. According to USAID, the purpose of the grants was to help reformist political parties strengthen their organizations and their role in elections, parliament, and local government.41

These cases reflect a larger pattern: in general, donors assisted Central and Eastern European groups associated with people whom the West identified with programs of market reform (such as that of Finance Minister Leszek Balcerowicz in Poland, where the most vocal alternatives to the Balcerowicz program were postcommunist or nationalistic populist programs). In other words, economic agendas appear to have been the decisive factor in many aid decisions said to be about democracy, pluralism, or civil society.

Significant differences characterized the structures within which aid was distributed in Central Europe, as compared with Russia. To begin with, although reform-oriented groups in Central Europe garnered much of the aid, they did not have a monopoly on it, in contrast to the Russian “clan” that we will observe in detail in chapter 4. Moreover, very different institutional and legal frameworks developed in the 1990s in Russia as compared, for example, with Poland, where there is little evidence of criminal mafia infiltration in the political establishment, as there is in Russia.42 Polish recipients generally operated in a more transparent and accountable way, and their primary motivation was largely to build a political base, not self-enrichment, in contrast to some Russian recipients.

Still, citizens in Central Europe and Russia raised many of the same concerns, albeit often with different intensity. Although, from a donor’s point of view, one can understand the homily that “helping someone is better than helping no one,” the meddling in local politics that the “help” sometimes created puts the wisdom of this belief in doubt. Support of one group to the exclusion of others built up certain elites—indeed, helped to crystallize some in the first place. The groups with enough clout and Western contacts to get foreign money gained steadily, while others with just as much indigenous support but less visibility in the West—and, thus, less foreign monetary support—lost ground.

Arguably, this reality had both positive and negative aspects: On one hand, those supported by the West were sometimes the people best equipped to be leaders and make critical decisions. On the other hand, resentment was stirred up among those outside the networks—especially among those who would likely have been in leadership positions if people had been chosen primarily on the basis of expertise. This concentration on a select few contributed to resentment especially because the few beneficiaries tended to distribute money and favors based on group loyalties and obligations. For donors to overcome this dilemma would have required in-depth knowledge of the histories and politics of local groups—expertise they seldom sought or appreciated the value of.

Once again, then, Western donors seemed to be caught in a paradox: To achieve their stated reform goals (in this case, of pluralism, civil society, and democracy), they selected and promoted specific political parties and groups. But this strategy seemed more likely to help narrow, rather than to widen, the range of participation.

LEFT-OUT LOCALITIES

Throughout the region, the groups favored by most donors were typically located in large cities such as Budapest, Warsaw, Kraków, Gdańsk, and Prague, particularly in the immediate post-1989 aftermath. In the rush to move funds quickly in the first years of the aid effort, donors concentrated on cities that were centers of government, even when their projects had no link to government. Donors hoped that funds would “filter down” to the localities. However, without accountability and incentives for dispersal, funds typically stayed at the center.

Many local leaders, who had heard about and were eager to accept the massive foreign aid that was said to be on its way, did not view this development favorably. Tadeusz Wrona, mayor of the Polish city of Częstochowa, declared in April 1991 that foreign aid “should go to big towns and counties, not to [the] Warsaw government.… If it goes to Warsaw, nothing will get to us.… If there’s to be real help from the West, you have to strengthen the counties. Because if the county goes bankrupt, we’ll have to go back to the old centralized system.” Nevertheless, prosperity was not far away, although not often as a result of foreign aid: During the 1990s, markets and business infrastructure developed very quickly in certain cities and areas (as described in chapter 5), including Częstochowa. The effects of these changes were soon felt in many of the smallest of towns and communities in Poland.

Some donors succeeded at providing decentralized aid. Germany, which shares borders with Poland and the Czech Republic and also is active in Hungary, took advantage of its proximity, knowledge of these countries, and issues of mutual interest to develop links and projects in an attempt to achieve influence in Central Europe. Much of Germany’s aid to Central Europe went directly to the localities. In this model, aid flowed from one land (region) to another land with an emphasis on cross-border initiatives, especially between Germany and Poland. The point of departure, the delivery mechanisms, and the targets all were decentralized.43 This land to land approach has earned a reputation for facilitating valuable cross-border cooperation in commercial and cultural exchange in many areas44 and also has been employed farther east.

By the mid-1990s, the United States and the EU targeted much more aid to the localities. These donors invested in some projects, several of which dealt with business and infrastructure development (described in chapter 5), that effectively tapped into local knowledge and worked with the localities. Between 1994 and 1998, the EU committed 18 percent of all PHARE monies to cross-border cooperation between recipient countries and their adjacent EU neighbors and to addressing the development problems that they may face.45 However, the instruction that might be gleaned from any effective projects was little considered farther east.

PARLOR POLITICS

A look at aid distribution in Central and Eastern Europe helps to explain why understanding the dynamics of the individual countries was so important and what happened when donors overlooked them.

The fall of communism had brought an “open historical situation”—a period of immense structural change, in which a new universe of possibilities suddenly comes into being—as historian Karl Wittfogel has termed it.46 Such open moments encourage a free-for-all environment in which unclaimed resources and untapped opportunities are pursued. In the new East, those who were the most energetic, savvy, and, in some cases, unscrupulous were the most successful. Many others felt left behind as they watched their friends take advantage of opportunities. As an acquaintance expressed in 1995: “I feel that I’m on the dock and everyone else has taken off.”

With much of the state bureaucracy still entrenched, but disoriented, and with many social institutions in disarray or being dismantled, certain elites were well placed to get whatever they wanted—from business monopolies to great advantages in privatization. Opportunities were sometimes fleeting: They opened up for weeks or months, only to close as someone cornered them, laws or other circumstances changed, or better opportunities came along. The ambitions and activities of the players were not curbed by rules and regulations, which often were nonexistent, unknown, unenforced, or simply ignored. Many prominent Central and Eastern Europeans—and equally as many of their less prominent brethren—could not be pegged simply as lawyers, businessmen, scholars, or consultants. They had their fingers in a kitchenful of pies and were adept at cultivating international contacts. Unlike in some Western countries, where control of much more of the political economy was settled and where professional differentiation and conflict-of-interest practices were highly developed, in the new East, those who legislated and implemented law were often those who regulated change and were responsible for monitoring abuse.

As discussed in chapter 2, some Polish government officials operated consulting firms that did business with their own ministries. For example, the deputy minister of privatization in the first two postcommunist governments (those of Tadeusz Mazowiecki and Jan Krzysztof Bielecki), who was responsible for joint ventures, at the same time owned a consulting firm that specialized in such ventures. According to sociologist Antoni Kamiński, “[a] distinctive mark of the post-Solidarity elite’s rule was considerable tolerance of conflicts of interest.”47 And in a 1991 Polish banking scandal, speculators working with several state-owned Polish banks made off with hundreds of millions of dollars.48

Groups could wield extensive influence because of the contexts in which they were operating: where, to varying degrees, the rule of law was weakly established, “the rules were what you made them,” and interpretation and enforcement of the law was subject to much manipulation. The differences in legal context in the nations of Central and Eastern Europe were not sufficiently appreciated by donors, and that lack of appreciation reduced the effectiveness of Western aid. Aid agencies involved in these environments also could fall victim to such practices.

Also underappreciated by donors was the communist upbringing of Eastern partners. Donors failed to understand that, in some Central European nations, especially those that donors considered aid priorities, a limited “civil society” had existed long before the fall of communism.49 Central European dissidents had been only partly right about the absence of a civil society, as anthropologist Chris Hann has noted:

I was, and remain, very sceptical of the way “society” was invoked by some “dissident” intellectuals and by various commentators outside the region to imply that Eastern European populations were united in their opposition to socialist governments. In this discourse, civil society is a slogan, reified as a collective, homogenised agent, combating a demonic state.50

Many Central European scholars and dissidents had seen a wide gap between “state” and “society.”51 Polish sociologist Stefan Nowak developed this argument in his theory of the “social vacuum.” Nowak’s theory conceived of postwar Poland as an “atomized” society, its mediating institutions destroyed by war and imposed revolution. Family endured in harsh dichotomy to the state; an overgrown public sphere pressed heavily against the private. People collided with rigid institutions. Nowak evoked this vision in a single dictum: “The lowest level is the family, and perhaps the social circle. The highest is the nation … and in the middle is a social vacuum.”52

However, Nowak and his followers overlooked the degree to which their societies had evolved alternative institutions; this fact fit neither Western nor Eastern models. If Nowak were correct and there was no middle ground, it is difficult to imagine how bureaucratic systems, totally divorced from the community they allegedly served, could function at all, as clearly they did. In Central and Eastern European societies, many of the most vital institutions were intentionally nonpublic and insubstantial. The Nowak model overlooked the labyrinth of channels through which deals and exchanges were made, both between people as “themselves”—private individuals—and as representatives of economic, political, and social institutions. This complex system of informal relationships, involving personalized patron-client contacts and lateral networks, pervaded the official economy and bureaucracy and connected them to the social circle. Although not explicitly institutional, these relationships exhibited clear patterns.53

Under communism, the sudden and massive social changes throughout the region, notably the huge urbanization of the peasantry, contributed to the erosion of social norms. People became adept at operating in a twilight world of nods and winks, in which what counted was not formalized agreement but dependable complicity. Where organizing outside of state bodies was banned, people who dared to undertake such activities did so as part of a close-knit circle of some kind, in which enduring relationships, frequent contact, and the ability to verify reputation made trust a critical component.54 In the Polish case, this was the social circle, or środowisko (among intelligentsia often called salons), a trusted group of friends forged through family and social background. Members of the same parlor mixed socializing with politicking. Anthropologist Jeremy Boissevain has described such groups as “cliques,” made up of dense55 and multiplex56 networks whose members have a common identity.57 (Clique in this social anthropological meaning should not be confused with the Polish or Russian klika, which has very pejorative meaning.) Boissevain has noted that the clique has both an objective existence, in that “it forms a cluster of persons all of whom are linked to each other,” and a subjective one, “for members as well as nonmembers are conscious of its common identity.” Members of these publicly informal but internally rigorous elite circles worked together for years and developed intricate, efficient, and undeclared networks to get things done in the face of dangers and difficulties that intensify bonds. Civil society in the 1990s would, by definition, arise from—or at least against the backdrop of—those well-established relationships and organizational capacities.

FROM COMMUNISM TO CIVIL SOCIETY?

In the late 1980s, as Central and Eastern European states weakened and exerted less control over organizations independent of them, there was an outburst of activities that challenged the state and its restrictions—especially in Poland and Hungary, the nations most tolerant of such activities. Although little organizing outside the state was officially permitted, even before the political revolutions of fall 1989, starting an organization or business had become a ticket to success in Poland.58 As communism began to loosen its reins, some noncommunist elites began to create voluntary associations that were illegal, but sometimes tolerated, for purposes ranging from improved housing and environment to halting the construction of nuclear power plants.

Through “social self-organization,” these new standard-bearers of civil society sought to revive long-suppressed civic values and grassroots organizations. But organizing itself was often more important than a group’s stated purpose: The very act of bringing together like-minded colleagues and drafting a manifesto was sometimes the most essential activity of a group’s entire history. Although most of these groups were not explicitly political, their very founding was a political statement in countries that, at best, shakily tolerated them.59

In 1989, members of these elite cliques emerged to direct their energies simultaneously into a number of arenas, including business, government, the international domain, and also politics. Because the groups operated in many arenas beyond the political, it was misleading to assume that they were just another form of interest group, faction, or coalition—conventional categories often used in the fields of comparative politics, public administration, and sociology. The potential influence of the clique was much more widespread and monopolistic than that of interest groups, factions, or coalitions. Cliques served to mediate between the state and private sectors, as well as between bureaucracy and private enterprise. Ill-equipped to deal with such a phenomenon, conventional social science could not sufficiently explain the role of cliques in changing state-private and political-administrative relations.60

Another feature of these cliques—and another departure from conventional models—is that they, not the individual, typically chose how to respond to new opportunities. Economists usually consider individuals as the primary unit of response to economic opportunities, but in the new East, the more correct unit of analysis of response to economic incentives was often the clique. Operating as part of a strategic alliance enabled the clique’s members to survive and thrive in an environment of uncertainty.

With crumbling states and weak institutions, Central and Eastern European cliques had wide latitude and few restraints. They tended to pursue their own agendas, regardless of their connections to formal institutions. They were “institutional nomads,” because circumstances demanded loyalty to the group but not necessarily to the formal institutions with which the members of the group were associated.61 For example, a civil servant (dependent on the tenure of a specific political leadership, if not actually brought in or bought by it) was typically more loyal to his or her clique than to some weak “office.” Another result of this state of affairs was that resources and decision making in economic, political, and social spheres tended to be concentrated in just a few hands.

Like the “big men” of Melanesia, whose position depends on their ability to maintain personal prestige and the prestige of the group, figures such as Adam Michnik were larger-than-life institutions in themselves. Their standing did not stem so much from formal authority or title, but from abiding informal authority and reputation. They were more than the sum of their titles, and special access to Western aid compounded the advantages. Just as Melanesian big men accumulate wealth and regularly hold feasts and shower lavish gifts upon their less eminent tribesmen, Central and Eastern European big men were expected by those in their circles to carry out certain duties, among them giving to those less privileged. They offered their members perks such as Western contacts and business clients and trips abroad sponsored by Western foundations. This arrangement enhanced the clout, internal political standing, and symbolic capital of the privileged men, which in turn served to enhance their reputations in the West. Naturally, those who were indebted to these men also sang their praises abroad and reinforced their authority and mystique. It was a self-fulfilling and self-perpetuating cycle.

The initiatives of the big men were often more informed by politics than the donors expected. Western funding reinforced the ability of certain influential groups to shape all aspects of economy, politics, and society, undeterred by the rule of law. What did this portend for the efforts of Western donors, whose stated goal was to encourage the development of a civil society? Because many funds went to groups that were exclusive, informal, de facto political clubs, they helped to reinforce the clubs rather than to widen political participation or to “build democratic institutions.” Some funds empowered entrenched political and economic cliques and power brokers, in some cases undercutting legitimate state institutions and governance.

A critical civil society question concerns the capacity of these groups to expand beyond their originating circles. Would they remain exclusive or would they attract new members on the basis of common interests? Under communism, the groups and networks that made up “civil society” were, by their very creation, making a political statement. After the collapse of communism, “the public domain underwent a rapid bifurcation,” as Grzegorz Ekiert and Jan Kubik describe it: “Two separate (at least in Poland) domains emerged: a vibrant and growing domain of civic associations and organizations and a more torpid and elitist domain of political parties and ‘political’ interest groups.”62

Generally, voluntary associations and political movements form themselves around new leaders, issues, and interests, rather than around long-established relationships. Several social scientists point to the restricted capacity of voluntary associations to expand beyond their originating circles, a contention borne out by the behavior of many Central and Eastern European groups.63 Although their inability to expand limited the creation of a more extensive civil society, organizing around common interests continued to evolve, at least in some contexts.

The case of Poland, which before the fall of communism probably had the region’s most advanced “civil society,” albeit based on deep-rooted associations, suggests that building a civil society based on common interests was not so easily accomplished. In the early 1990s, there was little apparent coalition building among social circles; the creation of coalition movements with national political goals seemed especially difficult. Some circles were made up of members of the old communist establishment; others comprised members of the old anticommunist one, such as the Solidarity activists drawn from Poland’s intelligentsia-Opposition establishment. There was much antagonism among the latter: The divisions within Solidarity-Opposition64 were especially visible following the deep social conflicts among circles that surfaced during the presidential campaign of late 1990. The Warsaw-Kraków Opposition circle (from which was largely drawn the government of Prime Minister Mazowiecki) confronted Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa, and his followers in a bitter social conflict that smoldered long after the election.

Scant research has been done thus far on coalition building in the region and emerging patterns of social organization. However, there is little in the legacies of communism and of the fragmented nature of postcommunist political systems to suggest that significant capacities for coalition building among cliques developed in the 1990s in many Central and Eastern European settings. In Russia, for example, nearly $1 million in U.S. funding from NDI and NRI to support “reformist” political parties yielded few results, according to the GAO: “Despite the institutes’ work, reformist parties have been either unwilling or unable to form broad-based coalitions or build national organizations and large segments of the Russian public have not been receptive to their political message.”65 Anthropologist Hann rightly determines that, despite multiparty elections and robust promotion of market-oriented economic policies, “it has not been easy to establish the rich network of associations outside of the state that comprises the essence of the romanticized western model of civil society.”66 Political scientists Ekiert and Kubik likewise conclude that “the postcommunist civil society represents a complex amalgam of old and new organizations and is often characterized by considerable fragmentation and political divisions.”67

NGO SPEAK

By the time the Iron Curtain parted and exposed private groups to the West, the development community had been supporting NGOs for about a decade.68 NGOs were, as Sampson has noted, “creatures of the global community of democratic rhetoric, of human rights, of grants, conferences, lobbies and politics, which characterizes East-West relations generally.”69 A recent Carnegie Endowment-sponsored study of foreign-funded NGOs in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union found that “local groups proliferated in Poland, Hungary, Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan often around issues that Western donors found important, but rarely around issues that locals confronted on a daily basis.”70

The philosophy underlying the NGO movement held that recipient groups could do all sorts of good things that traditional projects attempting “development” through governments could not: build community capacity, propose solutions to local problems, and provide a social safety net. And so NGOs became a doubly attractive opportunity for donors. NGOs were a special favorite of the United States, with its emphasis on funding the “private” sectors of Central and Eastern Europe.

Amid the drive to create NGOs, however, donors often lost sight of the extent to which NGOs, like “civil society,” represent models, that is, ideal representations of how things ought to work. Sampson has observed that “as models, they do not actually operate that way in those countries which are exporting them.”71 The same appears to be true in the countries to which NGOs are exported. The Carnegie Endowment-sponsored study concluded that “Western NGOs have played a large and important role in the design and building of institutions associated with democratic states. These same strategies used by NGOs, however, have had minimal impact on how these new institutions actually function.”72 A popular handbook for Russian environmental groups translated concepts such as strategic planning, fundraising, and press releases as “strategicheskoe planirovanie,” “fandraizing,” and “press-relizy,” an indication of their alien nature.73

Part of the problem was that the NGOs exported by the donors were frequently at odds with Second World legacies. Whether their ostensible purpose was social welfare, election education, or improvement of environmental conditions, NGOs were seen as furthering “transition,” or at least as being important by-products of these other endeavors. This interpretation assumed that the emerging NGOs were similar to their Western counterparts, despite the very different conditions under which they developed and operated. But many of the donors’ assumptions about how NGOs would operate and what they would contribute were inaccurate in the new contexts. “Voluntary,” “private,” and “philanthropic” initiatives were permeated by the market and politics. NGOs could play productive roles, but they were not necessarily equipped to be the building blocks of democracy that the donors envisioned.

Even the vocabulary used to describe the concept of NGOs, usually adopted from English, was confused in the context of Central and Eastern Europe. “Third sector,” “independent sector,” “private voluntary sector,” “nonprofit sector,” “charitable organization,” and “foundation,” defined in varying ways even in the West, all were mouthed by Eastern counterparts, often with only the vaguest notions of their meanings and of the legal-regulatory regimes from which they sprang. Jakub Wygnański, a sociologist and expert on Central European NGOs, has observed a “lack of communication” between East and West in which people used the same terms to mean different things.74

For instance, NGOs in Central Europe generally incorporated themselves as either foundations or associations. Registering as a foundation typically provided more favorable legal and tax advantages than registering as an association. Foundations were usually service-providing groups that did not give grants (as they would have in the West), but raised money in order to carry out activities themselves. Foundations encompassed a number of types of organizations, including larger and more stable NGOs and the region’s few grant-making organizations. On the other hand, most small, grassroots-oriented NGOs organized around common interests were registered as associations.75 By 2000, in Poland, for example, there were more than 5,000 foundations and some 21,000 associations.76

The Support for East European Democracy (SEED) legislation of 1989, which authorized millions of dollars to the region to “promote the private sector [and] democratic pluralism,” specified that funds should go only to private entities in Central and Eastern Europe. But at the time the donors arrived, institutional arrangements between private and state sectors were shifting. Given the complex (and diverse) interrelationships of state, private, and civil societies that had emerged in the region, there was evidence to suggest that these relationships would eventually take a different shape from those generally familiar to donors. The donors’ faith in the private sector also appeared simplistic in light of the complex and diverse state-private institutional arrangements that Western democracies themselves had developed. (For example, most American and British NGOs, although “private,” receive some governmental funding.)77 Given the fact that the state remained a major source of resources, demarcation between private and governmental organizations was often obscure.

As many different forms of ownership emerged in the latter days of communism, state employees such as managers “acquired” state enterprises or portions thereof, all the while maintaining some relationship with the state. After 1989, private-state institutional arrangements built on, and further developed, this model. For example, some Hungarian and Polish officials interested in attracting Western funds earmarked for NGOs had little trouble bypassing the private-sector requirement. They started “nonprofit” organizations attached to their state agencies. While state employees actually received the money, it still could be categorized as going to the private sector.

Even in Poland, which has enjoyed some success in its economic reforms, ambiguous state-private relationships appear to be institutionalized. Since 1989, legislative initiatives have enabled the creation of corporate, profitmaking bodies, which are formally nongovernmental but that use state resources and “rely on the coercive powers of the state administration,” as sociologist Kamiński has analyzed it.78 These bodies make it legally possible for private groups and institutions to appropriate public resources to themselves “through the spread of political corruption.” Kamiński elaborates:

One way of obliterating the distinction between public and private consists in the creation of autonomous institutions, “foundations” or “agencies” of unclear status, with broad prerogatives supported by administrative sanctions, and limited public accountability. The real aim of these institutions is to transfer public means to private individuals or organisations or to create funds within the public sector which can then be intercepted by the initiating parties.79

These state-private entities, lying somewhere between the state and the private sector,80 are enshrouded in ambiguity. They are part and parcel of the “privatization of the functions of the state,” as Piotr Kownacki, deputy director of NIK, the Polish government’s chief auditing agency, puts it, and they represent “areas of the state in which the state is responsible but has no control.”81 The entities’ “undefined functions and responsibilities” are a defining characteristic, as Kamiński explains: “From the government’s point of view, [these entities] have the legal status of private bodies, whereas from the point of view of the collectives controlled by these bodies, these are public institutions.”82

Given such institutional arrangements, then, it is not surprising that Central and Eastern E uropean NGOs often distributed Western perks to themselves and their peers on the basis of favoritism rather than merit. Those charged by the West with public outreach were often not equipped for that role.

Another important variance between Western NGO models and Eastern realities was the difference in attitudes and practices concerning trust in the workplace, especially in the early days of “transition.” Central and Eastern European groups often were unwilling to share information or otherwise cooperate with anyone who had not reached the status of personal friend. Sampson observes that “Westerners seem to be able to cooperate successfully even when they do not know each other at all, and in spite of having diverse political opinions, lifestyles and tastes. Put another way, work colleagues in the West can work well together on the job without ever becoming friends.” This ability to cooperate contrasted with the Eastern European NGOs he has observed, in which deep-rooted trust was a prerequisite to being able to work together. Along these lines, anthropologist Marta Bruno has observed the following:

The practice of bringing together in a workshop different groups of recipients who do not know each other can also have a boomerang effect. Individuals in post-socialist societies still tend to privilege those social relations determined exclusively through personal connections. Strangers are to be trusted only if they are linked by a common acquaintance who is also trustworthy. This system operates as much in the public and work spheres as it does in the private one. Unless western project workers have good and close personal relations with the recipients and therefore can serve as a guarantee of trustworthiness, it can be counterproductive to bring together previously unacquainted recipients. Given the usually limited amount of resources of aid projects, other recipients are seen as undesirable competition and the dominant attitude is one of suspicion. Furthermore, intricate cultural attitudes stemming from ethnic, social and gender stratification may also come into play and reinforce negative reciprocal feelings. These frameworks of social relations usually escape Westerners’ sensibilities, unless they are project workers with extensive knowledge of local cultures.83

Sampson adds that, to be successful in the new environment, NGOs had “to start realizing that the essence of democracy is not cultivating friends but ‘doing business’ with allies. This doing business is part of civil society in the market sense. Even market competitors who hate each other—mafia gangs, for example—can often find a common interest to do business together.”84

In the absence of sophisticated, well-conceived incentives on the part of donors to help build bridges among recipient groups, funding frequently inspired competition among groups, rather than cooperation, and served to reinforce existing hierarchies. Bruno has written that “Russians have accepted the ‘given’ of international aid and co-operation projects (whether wanted or not) and are weaving them into the complex system of patronage, social relations and survival strategies which are taking shape in post-socialist Russian reality.… Presumably involuntarily, donor agencies are offering, through development projects, new sources for reinforcing the elitist, feudal-type system of social stratification.”85

Anthropologist Hann has likewise concluded: “The focus [on NGOs] has tended to restrict funding to fairly narrow groups, typically intellectual elites concentrated in capital cities. Those who succeed in establishing good relations with a western organisation manoeuvre to retain the tremendous advantage this gives them. The effect of many foreign interventions is therefore to accentuate previous hierarchies, where almost everything depends on patronage and personal connections.”86

Another effect arises from dependence on foreign funding. With the outside donor as chief constituent, local NGOs are sometimes more firmly rooted in transnational networks than in their own societies. The Carnegie Endowment-sponsored study cited earlier noted that the dependence of local NGOs on Western assistance “often forces them to be more responsive to outside donors than to their internal constituencies.… Their dependence has the unintended consequence of removing incentives to mobilize new members and of fostering inter-organizational competition for grants that breeds mistrust, bitterness, and secrecy within and between organizations.”87

And so, while neglecting groups with laudatory goals and indigenous support, donors sometimes funded organizations that were not operating in the public interest, especially in the initial period of East-West contact.

THE GREEN JET SET

A case in point was the Regional Environmental Center. In 1989-90, Western donors targeted the environment as a top funding priority, not only for the well-being of Central and Eastern Europe but also for the benefit of Western Europe, which was near enough to be damaged by its neighbors’ nuclear power plants, acid rain, or polluted waterways. So Western funders, especially foundations and bilateral donors, supported the environmental movement, largely by funding NGOs both directly and indirectly.

The antecedents of the environmental movement were Hungary’s Danube Circle, Czechoslovakia’s Green Circle, and other groups in the region that had challenged communism as they fought for environmental causes. Strongest from 1986 to 1989, the “environmental movement” included many people who used it as a means to engage in activities against or outside the state.

Given the movement’s multipurpose nature, it was natural that, once communism fell, many of those previously involved in the movement, who now could pursue other endeavors unconstrained, abandoned it to do just that. A wave of environmentalists—leaders of the region’s environmental organizations—stepped into key government posts in Central Europe. There, many abandoned environmental concerns in the name of budget cuts and helped to institute the shock therapy and other austerity measures of the day.

Meanwhile, the Western environmental and aid communities underwrote the region’s elite environmentalists. In 1990, Austria, Canada, Denmark, the EU, Finland, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United States donated some $20 million to the Regional Environmental Center, housed in a charming old silk mill in Budapest. Created as a result of the SEED legislation, the center had been conceived as a catalyst for activity throughout the entire region and attracted considerable donor resources. Its mandate was to develop institutional capabilities and outreach programs and to promote public awareness and participation.

Under the leadership of Executive Director Peter Hardi, a former communist, the center had weak links to the Hungarian government as well as to the region’s governmental bodies and environmental ministries. “An institution to give out money,” the Center awarded grants in ways that “divided the NGO community,” as István Tökés, an official in the Hungarian Ministry of the Environment, explained.88 Having virtually no agenda of its own, the Center disbursed money to favored environmental groups throughout the region, which were supposed to conduct studies and public outreach activities. Elena Petkova, a former board member of the Center, confirms that Hardi “failed to support any kind of mechanism to make grants competitive. He didn’t try to build capacity and there was no transparency. People got grants if they knew him or someone on the board.”89 Consequently, the Center fulfilled little of its public outreach mission, especially in its initial years.

In a setting in which there was little precedent for making information available to citizens, either for free or at all, the aid-funded environmental NGOs responsible for gathering and disseminating environmental information to the public often guarded the information they acquired and made it available only at a price. With resources in short supply, organizations and individuals tended to use the money and perks they received to broaden their own opportunities and enhance their résumés, rather than to develop environmental policy or support clean-up activities. It was hardly a step toward the civil society that donors thought they were underwriting.

This state of affairs was mirrored in the environmental ministries and institutes. State-run agencies that had been massively subsidized in the old system suddenly lost their funding or saw it dramatically cut. Their chief resources became their databases, such as geographical survey or monitoring information. In some scenarios, one branch of government sold to another.

Given the competitive atmosphere, it was not surprising that the NGOs often declined to share information and advantages with others and conducted little outreach. A few “environmentalists” spent their time on the international conference circuit, largely working their own contacts and opportunities. One Hungarian environmentalist spoke of herself and her colleagues as the “green jet set.”90 Moreover, according to the GAO, the Regional Environmental Center’s “early operations suffered from financial management and programmatic weakness.”91 As a result, USAID withheld approximately $1.4 million, about one-third of U.S. funding to the Center, until evidence could be provided that its operations had been improved,92 and Director Hardi resigned after being asked to leave by the donors.93

Given the fact that U.S. aid’s main job was to sign up projects and contractors and “to get the money out the door”—and there was considerable pressure from multiple sides to do so—intervention in problematic projects and admissions of failure were unusual. Consciously or unconsciously, project officers had incentives to go along with contractors and collude in the process. But U.S. aid officials took the uncommon step of trying to reorient the Center, an indication of the gravity of its problems. Following a financial and management audit in 1992, the Center was radically reorganized. With donors and recipients working together, the Center’s management and financial practices, program direction, and criteria for giving grants to NGOs all were revamped, a finding that the GAO independently confirmed.94