A Few Good Reformers: The Chubais Clan, Harvard, and “Economic” Aid*

The story … begins … when an idealistic, but pragmatic “St. Petersburg mafia” of young economists led by Mr. [Anatoly] Chubais … infiltrated the power structure in Moscow.… It is the story of how a modest amount of funding from the United States Agency for International Development enabled a handful of bright kids from Harvard and a few dozen middle-aged pros from Wall Street to help the Russian privatization agency begin to build the regulatory framework and trading infrastructure necessary to develop the new securities market.

—Briefing paper prepared for USAID by the “Harvard Project,” the chief conduit of U.S. economic aid to Russia1

THE DISSOLUTION OF THE SOVIET UNION in December 1991 and the end of the Cold War paved the way for the aid story to move east. The West began a repeat performance of its efforts in Central and Eastern Europe: International lending institutions and the foreign aid community pressed for economic reform and the privatization of state-owned resources; donors promised billions of dollars in aid to the former Soviet republics. Many aid programs set up in Central and Eastern Europe were transported to Russia and the other former republics; a host of Western consultants moved with them. By 1994, aid to Russia was in full swing.2

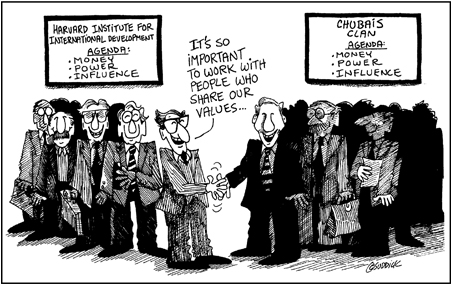

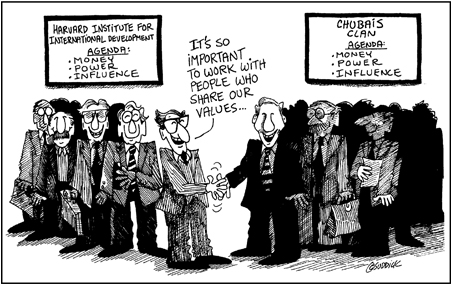

It had been damaging enough when Western donors selected a few groups in Central and Eastern Europe to receive aid, especially when the donors barely knew whom they were supporting. But in Russia (and later Ukraine), major donors—particularly the United States—took this approach to an extreme. The United States placed its economic reform portfolio—set up to help engineer the enormous shift from a command economy to free markets—into the hands of a single group of self-styled Russian “reformers.” From 1992, when aid first appeared, through much of the decade, U.S. economic aid to Russia was entrusted to these men, who were dominated by a long-standing group of friends from St. Petersburg that Russians called a “clan” (here referred to as the “St. Petersburg Clan” or the “Chubais Clan,” after its leader, Anatoly Chubais). This Clan worked closely with Harvard University’s Institute for International Development (HIID) and its associates to establish and run a Moscow-based program that leveraged U.S. support. The program served as the gatekeeper for hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and G-7 taxpayer aid, subsidized loans, and other Western funds and was known simply as the Harvard Project.3

The Clan came to control, directly and indirectly, millions of dollars in aid through a variety of organizations that were set up to bring about privatization, legal reform, the development of capital markets, a securities and exchange commission, and other economic reforms.4 Through these organizations, two Clan members alone became the gatekeepers for hundreds of millions of dollars in aid money and loans from international financial institutions. U.S. support also helped to propel Clan members into top positions in the Russian government and to make them formidable players in local politics and economics. U.S. support bolstered the Clan’s standing as Russia’s chief brokers with the West and the international financial institutions. The aid seemed to yield results, notably the transfer of a large number of state-owned companies to “private” ownership.

But was economic reform the driving agenda of the Chubais Clan? And what made it deserve the status of partner with the West more than other Russian reform groups? More important, did the strategy of focusing largely on one group further the aid community’s stated goal of establishing the transparent, accountable institutions so critical to the development of democracy and a stable economy for this world power in transition? As in Central Europe, what were the long-term implications in Russia of supporting one group of reformers at the expense of others? From the very beginning, Russian observers took note of the activities and motivations of the Chubais Clan. But it would not be until the late 1990s—and the eruption of a scandal that could hardly be ignored—that many Western observers would begin to consider the implications of U.S. and Western policy and what it had wrought.

THE FORGING OF THE HARVARD—ST. PETERSBURG PARTNERSHIP

In the late summer and fall of 1991, as the vast Soviet state was collapsing, Harvard professor Jeffrey Sachs and other Western economists participated in meetings at a dacha outside Moscow where young “reformers” planned Russia’s economic and political future. Boris Yeltsin, then in the leadership and undermining Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet Union (which would break up by year’s end), was building his teams of advisers—and the men from St. Petersburg were to figure prominently in that team. Their vital Western contacts distinguished them from other groups looking to have a hand in shaping Russia’s economic policy.

It was the springtime of East-West courtship. Russia seemed a blank slate ready for reform; dramatic change was in the air. The West fell in love with the new faces cast from its own ideological mold, and this cadre of “reformers” assumed the role that the West had created for them. They promised quick, all-encompassing change that would remake Russia in the Western image and eliminate the vestiges of communism.

At the dacha, Sachs and several other Westerners, some of whom were senior members in a project paid to Sachs’s consulting firm, Jeffrey D. Sachs and Associates, Inc.,5 offered their services and access to Western money. They would provide the theory and advice to reinvent the Russian economy. The key Russians present were Yegor Gaidar, the first “architect” of economic reform, and Anatoly Chubais, who was part of Gaidar’s team and later would replace him as the “economic reform czar.” Individual Russians paired off with their Western counterparts to work on economic policy. Chubais, with his savvy, American self-starting style, found common ground with Andrei Shleifer, a Russian-born émigré who, still in his early 30s, had climbed to the pinnacle of academic success in America as a tenured professor of economics at Harvard and who served as a senior member in Sachs’s consulting project named above. Shleifer met Chubais through Sachs, according to a book co-authored by Shleifer.6 Both Shleifer and Chubais were young, ambitious, and apparently eager to make economic policy history. They combined forces to plan the privatization of Russia’s state-owned enterprises.

Supporting the Sachs-Gaidar-Chubais policies (though not at the dacha meetings) was yet another Harvard man, Lawrence Summers. In 1991, Summers was named chief economist at the World Bank. Summers would later occupy the posts of undersecretary, then deputy secretary, and, finally, secretary of the Treasury. In 1993, newly inaugurated President Clinton appointed Summers under secretary of the Treasury for international affairs. In this role, Summers was directly responsible for designing Treasury’s country-assistance strategies and for the formulation and implementation of international economic policies.7 He had deep-rooted ties to the principals of Harvard’s Russia project. Shleifer credits Summers with inspiring him to study economics;8 the two received at least one foundation grant together.9 Summers’s publicity quote for Privatizing Russia, a book co-authored by Shleifer, declares that “[t]he authors did remarkable things in Russia and now they have written a remarkable book.”10

Summers had also long been connected to Sachs, his colleague from Harvard. Summers hired Sachs’s protégé, David Lipton, a Harvard Ph.D. who had been vice president of Jeffrey D. Sachs and Associates (and who, together with Sachs and Shleifer, was listed as a senior member of the Sachs consulting project), to be deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury for Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. After Summers was promoted to deputy secretary in 1995, Lipton moved into Summers’s old job and assumed “broad responsibility” for all aspects of international economic policy development. Lipton and Sachs published numerous joint papers and served together on consulting missions in Poland and Russia. “Jeff and David always came [to Russia] together,” remarked Andrei Vernikov, a Russian representative at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). “They were like an inseparable couple.”11 According to Vernikov and other sources, Sachs presented himself as a power broker who could deliver Western aid.

Sachs helped Gaidar, who served as minister of finance and the economy from November 1991 to April 1992, then as first deputy prime minister, followed by acting prime minister to December 1992, promote a policy of “shock therapy,” which aimed to swiftly eliminate most of the price controls and subsidies that had underpinned life for Soviet citizens for decades.12 Gaidar, Sachs, and their supporters believed that such a policy would lift the nation out of the doldrums of its command economy and set it on the bright road to capitalism. Shock therapy did free most prices, but it did not pay sufficient attention to the fact that the economy was monopolistic. Many experts believed that shock therapy contributed significantly to the subsequent hyperinflation of 2,500 percent. One result of the hyperinflation was the evaporation of much potential investment capital: the substantial savings of ordinary Russians.13 By November 1992, Gaidar was under severe attack for his failed policies. He was ousted in December of that year. Despite a brief return as first deputy prime minister, Gaidar continued his policy influence primarily behind the scenes.

Chubais took over where Gaidar left off. According to some Westerners’ reports, he was much more presentable than Gaidar. He seemed suave and well spoken. Then in his mid-30s, Chubais was adept at cultivating and charming his Western contacts. The British magazine Economist predicted a future for Chubais as Russian president by the year 2010.14 Western politicians and investors came to see him as the only man capable of keeping the nation on the troublesome road to economic reform. Chubais was on intimate terms with some Western officials, including high officials of the World Bank, the IMF, and the U.S. government, including Deputy Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers. In a letter of April 1997 (obtained and published by a Russian newspaper) addressed “Dear Anatoly,” Summers instructed Chubais on the conduct of Russian foreign and domestic economic policy.15

To help him in his appointed task, Chubais assembled a group of Westward-looking, energetic associates in their 30s, many of whom were long-standing friends from St. Petersburg. From the start, the “young reformers” and their Harvard helpmates chose rapid, massive privatization as their showcase reform. The Harvard group secured awards from the U.S. Agency for International Development for work on privatization and other economic reforms and channeled them through the Harvard Institute for International Development. According to Treasury official Mark Medish, “Sachs was the one who packaged HIID as an AID consultant.”16 Harvard economist Shleifer became director of the Institute’s Russia project. Another Harvard player was a former World Bank consultant named Jonathan Hay, who played a minor part in the Jeffrey D. Sachs and Associates project.17 In 1991, while still at Harvard Law School, Hay had become a senior legal adviser to Russia’s new privatization agency, the State Property Committee (GKI).18 The following year, the youthful, hard-working Hay was made the Harvard Institute’s general director in Moscow.

With aid money and Harvard’s involvement, the St. Petersburg Clan, which Deputy Secretary Summers later called a “dream team”19 (an invaluable endorsement given his position and status), came to occupy important positions in the Russian government and ran a series of aid-created and funded “private” institutions. Made significant by virtue of hundreds of millions of Western dollars, Chubais was a useful figure for Yeltsin: first as head of the GKI, beginning in November 1991, then additionally as first deputy prime minister in 1994, and later as the lightning rod for complaints about economic policies after the communists won the Russian parliament (Duma) election in December 1995. Chubais made a comeback in 1996 as head of Yeltsin’s successful reelection campaign and was named chief of staff for the president. In March 1997, Western support and political maneuvering catapulted him to first deputy prime minister and minister of finance. Although fired by Yeltsin in March 1998, Chubais was reappointed in June 1998 to be Yeltsin’s special envoy in charge of Russia’s relations with international lending institutions.

Chubais’s success at courting power on all sides placed the Chubais Clan in a unique position. As Russian sociologist Olga Kryshtanovskaya explained it, “Chubais has what no other elite group has, which is the support of the top political quarters in the West, above all the USA, the World Bank and the IMF, and consequently, control over the money flow from the West to Russia. In this way, a small group of young educated reformers led by Anatoly Chubais turned into the most powerful elite clan of Russia in the past five years.”20

The interests of the Harvard Institute group and the Chubais Clan soon became one and the same. Their members became known for their loyalty to each other and for the unified front they projected to the outside world. By mid-1993, the Harvard-Chubais players had formed an informal, collusive and extremely influential group of “transactors” that was shaping the direction and consequences of U.S. economic aid and much Western economic policy toward Russia. “Transactors” work together for mutual gain, even while formally representing their respective parties. Transactors may genuinely share the stated goals of the parties they represent—in this case, the United States and Russia—but they have additional goals that may, advertently or inadvertently, subvert or subordinate the purposes of the parties they ostensibly represent.21 As a new decade begins, some key transactors in this story are under investigation for corruption and other criminal activities—the consequences of their undeclared goals. Recently, the U.S. government brought a suit against four American transactors and Harvard University. It alleges that the defendants “were using their positions, inside information and influence, as well as USAID-funded resources, to advance their own personal business interests and investments and those of their wives and friends.”22

HARVARD’S BLANK CHECK FROM UNCLE SAM

Without experience in Russia and under obligation to carry out congressional spending mandates, an insecure USAID was persuaded to largely delegate responsibility for America’s role in reshaping the Russian economy to the Harvard Institute group. The Institute’s first award from USAID for work in Russia came in 1992, during the Bush administration. Over the next four years, between 1992 and 1997, with the endorsement of influential proponents in the Clinton administration, the Institute received $40.4 million from USAID in noncompetitive grants for work in Russia. It was slated to receive another $17.4 million, but USAID suspended its funding in May 1997, citing allegations of misuse of funds.23 Approving such a large sum of money as a noncompetitive “amendment” to a much smaller award (the Harvard Institute’s original 1992 award was $2.1 million) was highly unusual, according to U.S. officials.24 Also highly unusual was the citing of “foreign policy” considerations—that is, the national security of the United States—as the reason for the waiver.

Nonetheless, the waiver was endorsed by five U.S. government agencies, including the Department of the Treasury and the National Security Council (NSC), two of the leading bodies making U.S. aid and economic policy toward Russia (and Ukraine). From Treasury, the Harvard-connected David Lipton and Lawrence Summers supported the Harvard Institute projects. In his capacity as USAID’s deputy assistant administrator of the Bureau for Europe and the New Independent States, Carlos Pascual signed the waiver on behalf of USAID. Pascual’s support for Harvard projects continued, and he was later promoted to the NSC, where he served as director of Russian, Ukrainian, and Eurasian Affairs from 1995 to 1999.25

Thus, through high government directives promoted by Harvard-connected administration officials, and with competitive bidding and other standard government regulations and procedures largely circumvented, the Harvard Institute secured terms that were different from, and more advantageous than, those for many other aid contractors. Further, key Harvard-connected officials were responsible for handing the Institute not only the bulk of USAID’s economic reform portfolio in Russia, but also the authority to manage other contractors. In addition to receiving tens of millions in direct funding, the Institute helped steer and coordinate USAID’s $300 million reform portfolio in grants to the Big Six accounting firms and other companies such as the public relations firm Burson-Marsteller.26 This put the Harvard Institute in the unique position of recommending U.S. aid policies in support of market reforms while being a chief recipient of the aid, as well as overseeing other aid contractors, some of whom were the Institute’s competitors. Louis Zanardi, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) official who spearheaded the GAO investigation of the Harvard Institute’s activities, adds that the Institute’s substantial influence was possible “because of its close relationship with the Chubais group and USAID.”27

Beginning in 1992, Jonathan Hay, the Harvard Institute’s general director and its public face in Moscow, served as a key link between the Chubais Clan and the aid community at large. Hay assumed large power over contractors, policies, and program specifics. He said he viewed his role as “getting policy focused right and turning that into a message for donors,” which included helping Chubais and others to prepare requests to the leadership of USAID that communicated what the Russian government wanted to do.28

Because of their special standing with high government officials, the Chubais-Harvard transactors were able to urge contractors to use certain institutions and people. Many consultants not connected to Harvard indicated that Hay had some control over their purse strings and that he spoke on behalf of the Russian government (that is, the Chubais Clan) to USAID and other Western organizations. Thus, it is not surprising that at a meeting that the author observed among Hay, representatives of the Clan, and senior aid-paid Western consultants, the consultants treated Hay with considerable deference.29

Hay had easy access to the powerful Chubais Clan and often served as its spokesman. Clan principals directed donor officials, contractors, and even GAO investigators wanting to talk to Russian officials responsible for aid to Hay. The Institute sometimes spoke on behalf of the Clan, sometimes on behalf of itself as an aid contractor, and sometimes also as a contractor managing the projects of competitor contractors. From an American perspective, the Harvard Institute appeared to have a conflict of interest.

All this meant that, in practice, and under cover of economic aid, the United States delegated to the Harvard Institute, a private entity, foreign policy in a crucial area that involved complicated choices. This arrangement eventually came under scrutiny. In 1996, Congress asked the GAO to investigate the Harvard Institute’s activities in Russia and Ukraine. The GAO found that “HIID served in an oversight role for a substantial portion of the Russian assistance program,”30 that the Harvard Institute had “substantial control of the U.S. assistance program,”31 and that USAID’s management and oversight over Harvard was “lax.”32

In 1997, as the result of yet another investigation, this time beginning with USAID’s inspector general (and later referred to the U.S. Department of Justice), USAID canceled nearly $14 million of its commitments to the Harvard Institute amid allegations that Andrei Shleifer and Jonathan Hay, the Russia project’s two principals, had “abused the trust of the United States Government by using personal relationships … for private gain.”33 In May 1997, citing evidence that the two men had used their positions and inside knowledge as advisers to profit from investments in the Russian securities markets and other private enterprises, the Harvard Institute fired them. In January 2000, a Harvard task force issued a report alluding to the financial scandal and recommending that the Harvard Institute be closed.34

In September 2000, in a suit brought against Harvard University, Shleifer, Hay, and their wives, the U.S. government alleged that the two men “were making prohibited investments in Russia in the areas in which they were providing advice.”35 Although acknowledging that they participated in and benefited from many of the alleged activities, Hay and Shleifer denied that their activities constituted a conflict of interest with their official positions. Tellingly, USAID Deputy Administrator Donald Pressley acknowledged: “We had even more than usual confidence in them [Harvard advisers], and that’s one reason we are so distressed that this has occurred.”36

A FEW GOOD MEN

Just what was this Chubais Clan? A core group of people who contacted one another for many purposes, the clan was a “clique,” as defined in chapter 3. The clique was a strategic alliance that responded to changing circumstances and helped its members promote common interests through concentration of power and resources.37 (As noted earlier, this use of “clique” should not be confused with the Russian klika, which has a decidedly pejorative connotation—that of an establishment gang.) Sociologist Olga Kryshtanovskaya explains the clique, or “clan” in the Russian context, as follows:

A clan is based on informal relations between its members, and has no registered structure. Its members can be dispersed, but have their men everywhere. They are united by a community of views and loyalty to an idea or a leader.… But the head of a clan cannot be pensioned off. He has his men everywhere, his influence is dispersed and not always noticeable. Today he can be in the spotlight, and tomorrow he can retreat into the shadow. He can become the country’s top leader, but prefer to remain his grey cardinal. Unlike the leaders of other elite groups, he does not give his undivided attention to any one organisation.38

Core members of the St. Petersburg Clan were originally brought together through university and club activities in the mid-1980s in what was then Leningrad. Most members of the Clan studied at the Leningrad Institute of Engineering Production, where Chubais was a student; the Institute of Finance and Economics; or Leningrad State University.39 Some also were associated with the Leningrad Shipbuilding Institute and the Leningrad Polytechnical Institute.40 Chubais was an active participant in ECO (Economics and Organization of Industrial Production), a club, and its namesake magazine, which was published by the Russian Academy of Sciences. According to Leonid Bazilevich, vice president of the club, who was Chubais’s professor and was acquainted with several members of the Clan, members were “very intensively connected” with one another at that time and “well-oriented to Western economic models.”41

Later, in the Gorbachev years of glasnost, some members of the Clan became involved in explicitly political activities and established an informal club that called itself Reforma. This club organized special meetings on economic issues that sometimes attracted hundreds of people. Reforma put together lists of candidates and platforms for local and national elections, as well as drafts of legislation and a business plan for a free-enterprise zone in Leningrad.42 Later, Chubais and other members of the Clan established a connection with the mayor of the city, Anatoly Sobchak, and became influential in its administration. In moving from academia to city government, “Chubais brought with him many of the brightest young scholars he had come to know working in Leningrad’s well-developed intellectual circles,” political scientist Robert Orttung has noted.43 Before going to Moscow, several members of the Clan served as first deputy mayor under Sobchak (Chubais, Alexey Kudrin,44 Sergei Belyaev, and Vladimir Putin—Russia’s new president). Some (Chubais, Belyaev, Eduard Boure, and Mikhail Manevich45) headed state privatization agencies there, and still others (Dmitry Vasiliev and Alfred Kokh46) worked as deputies in those offices.

Although later in Moscow, the St. Petersburg Clan took on some powerful members who were not from their hometown (notably Maxim Boycko from Moscow, whom Shleifer says he introduced to the Clan), all were tied and obligated to Chubais. Chubais and the Clan depended on, and appeared to work closely with, still others, such as Ruslan Orekhov, head of the president’s legal office. According to Shleifer, Orekhov’s association with the group began in 1993, when its members had to work with Orekhov because decrees went through his office.47

Although cliques do not necessarily have a center or leader,48 they have recognized authorities who often retain their standing and influence whether they shoulder responsibility or not. By skillfully manipulating others’ interests, a clique authority builds up a following of those who are under obligation to return past favors and support.49 According to Bazilevich, members of the Chubais Clan supported one another “in critical situations.”50

There were powerful reasons for the Clan to stick together after the breakup of the Soviet empire in 1991. Chubais called on its members to serve in key government positions. Operating as part of a strategic alliance was crucial to the Clan’s effectiveness in helping to run the country, as well as in tapping into lucrative opportunities.51 Members of the Clan discovered that, working together, their Western contacts could help them leverage foreign support for use as a political and financial resource at home. And, indeed, the Clan did serve as a critical launching pad and resource for Chubais.

NOBLE REFORMERS IN THE SHADOWS OF SOCIALISM

The Chubais Clan was well positioned to become the group of “reformers” favored by the West. Donors tended to identify the reformer as such, not because he was a change agent in support of market reform, but because he possessed the personal attributes that Westerners responded to favorably. Although the reformer might, indeed, have embraced market reform, the identity markers that Westerners appeared to recognize most often were a pro-Western orientation; the ability to speak English and to converse in the donor vernacular of “markets,” “reform,” and “civil society”; established Western contacts (the more known or influential, the better); travel to and/or study in the West (a privilege generally reserved for the economic elite); and, perhaps most important, a self-proclaimed identity (at least vis-à-vis the West) as a reformer who associated with other reformers.

The most popular Russian reformers in Western political and aid circles were young, energetic, and adept in their dealings with donors. As Donald Jensen, former second secretary at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, put it: “Absolutely, they knew how to play us.… And knew very consciously how to project what they wanted to an American audience and get the Americans to go along.”52

Westerners often took members of the Clan at face value. As USAID’s Thomas A. Dine stated, “If [Chubais associate] Maxim Boycko tells me that X, Y, and Z are reformers, I believe him.”53 Dine went on to note that “it’s no secret that nationalists and communists don’t like [Chubais], and perhaps that’s the best proof of all [of his reform credentials].”54 Western officials and the media promoted the of Chubais and the “Young Reformers” and overlooked other reform-minded groups. A self-promoting view that the only alternative to the Chubais Clan was the communists, loudly advanced by the Chubais-Harvard transactors (and by influential parts of the Western aid and political community), does not hold up under careful scrutiny. Throughout the aid story, at every step of the way, there existed viable and important alternatives to the policy choices that were made and to the West’s strategy of conducting economic reform through political support of the Yeltsin government and one clan.55

Identifying reformers on the basis of personal attributes and declared ideological positions, as they looked in the West, clearly had a cost: It alienated and often overwhelmed other reformers and potential reformers, as well as many Russians generally. Aleksandr Lebed, Russia’s national security chief, questioned Western perceptions of reformers throughout the aid effort. In 1996, his spokesman pointed to a common misperception by contrasting two governors:

We Russians and you Americans often use the same words meaning different things. For example “the true reformer”: Is it a friend of the West, as you usually think? We have two governors—one is considered by mass media to be a true liberal, reformer, market-thinker. He really uses only the market language, is West-oriented, young, has “camera appeal,” is full of energy and zeal. He has all the opportunities that the title—“true reformer”—affords him: support from Moscow and the West. The second reformer is called “Red,” almost communist, anti-reformer, old-thinker. No one can say that this man is the friend of the West and the central government. At first glance the picture is clear, there is no doubt: one is “the Reformer,” the other “the communist.” But in reality the first man can speak well and advertise himself to the West, while the other one tries to do little, slow but effective steps to achieve civilized market reform and does not care how he looks in the eyes of the mass media.56

In short, donors, by equating Western-oriented Russians with reform agendas and traditionalist or communist Russians with anti-reform agendas, created stereotypes. As political scientist Peter Stavrakis observes, these stereotypes made it “virtually impossible to conceive of a pro-reform Russian nationalist.”57

An even more fundamental problem with the view that the fate of the Russian political economy was being decided by a contest between a few good reformers and everyone else was that this belief overemphasized ideology and neglected the role of communist legacies in change processes. Although such a dramatic step as the breakup of an empire might have looked like a death followed by a resurrection, in fact it was more like a messy divorce involving custody disputes over young children. The emergence of the new Russian state in 1991 did not constitute a fresh starting point: Deep-rooted groups and processes helped to shape the very nature of the Russian state.

While the chief political analyst at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, Thomas E. Graham speculated that Russia is run by rival “clans” with largely unchecked influence.58 With unstable political, legal, and administrative structures, there were myriad opportunities for clans to penetrate public institutions and lay claim to resources. This state of affairs enabled clans to bypass other sources of authority and influence and thereby enhance their own. As the main rivalry among clans occurred within the executive branch, the Russian government could not ensure impartiality under the rule of law.

The Chubais Clan was so closely identified with particular ministries and institutional segments of government that the respective agendas of the state and the Clan sometimes seemed identical. The same was true of competing clans, which had similar ties with other government organizations, such as the Central Bank, the Ministry of Finance, and the “power ministries” (the Ministries of Defense and Internal Affairs, and federal security services). These clans depended on state authorities to stand far enough away from commercial activities so as not to interfere with the clans’ acquisition and allocation of resources, but close enough to ensure that no rival clans would draw on the resources. Under these circumstances, it would be unreasonable to expect that any ambitious group would neglect its own financial and political agendas, especially when it had been designated the sole beneficiary of so much aid.

What were the effects of concentrating aid on one particular clan, if the clan system was “business as usual” as in Russia? Was it realistic to expect that any clan would operate in a vacuum, especially when it was singled out to receive resources to which competing clans would not have access? Beyond this, given the Russian self-image of a wounded superpower,59 was it reasonable to expect that Western support of one particular clan in a highly politicized environment would not fuel charges of Western interference from other clans? Aid designed to promote a particular political group does not advance the building of institutions that are transparent and unaligned with any one clan. The goal of working toward such institutions is critical in structuring a democratic political and economic system, even if the goal is virtually impossible to achieve.

Although Western donors were inclined to view the loyalty exhibited by the Chubais Clan as part of its effectiveness, many Russians regarded the Clan as a communist-style group that was adept at commandeering resources for itself. The Chubais transactors’ primary source of clout was neither ideology nor even reform strategy, but precisely their standing with and their ability to get resources from the West. Long-established loyalty might mean “They’re effective” in the West, but in Russia it tended to mean “They’re sharing money.”

THE GREAT GRAB

The Chubais Clan’s partnership with the Harvard group took shape in 1991 and 1992, when Russian economic reform activities were centralized in the GKI. It was as the engine of Russia’s ongoing privatization that Chubais played his largest role—an admirable one in the eyes of international financial institutions and many Western governments; a sinister one to many Russians.

Shortly after Boris Yeltsin became the elected president of the Russian Federation in June 1991, the Federation’s Supreme Soviet passed a law mandating privatization. This was two months before the August coup attempt. In the confused political environment that followed the attempt, several schemes to realize privatization were floated before the Supreme Soviet.60

One was the brainchild of the Chubais-Harvard team. As the first head of the new GKI beginning in November 1991, Chubais, together with his team of St. Petersburg and Western advisers, drew up plans to privatize no fewer than 15,000 state enterprises. The team designed and coordinated the signature mass-voucher privatization program, launched in November 1992, in which citizens were given shares, or “vouchers,” in state-owned enterprises. USAID spent $58 million to underwrite this privatization program, including its design, implementation, and promotion.61 Through the Harvard Institute, USAID supported about ten advisers to the GKI,62 whose contracts added up to $7.75 million.63

In addition to USAID and the Harvard Institute, the Harvard group worked under other venues and funding. Project documents of Jeffrey D. Sachs and Associates state that “Professor Sachs, Dr. Lipton, and Professor Shleifer have worked with Deputy Prime Minister Chubais and the staff of the Russian State Committee on Privatization.… The [Sachs] team has had an extensive interaction with the [Russian] State Committee on Privatization and has helped in the design of the mass privatization program legislation recently enacted by Parliament.”64 The documents further state that Andrei Shleifer “has played a central role in the formulation of the Russian privatization program.…”65

A USAID privatization official explained that “it was essential to jump-start the mass privatization program. At that time there was enormous pressure to get things going.”66 At first blush, it indeed seems that things “got going”—the U.S. Department of State’s 1996 annual report on aid to the former Soviet Union declared that “Russia’s mass-privatization program was successfully completed in July 1994, with state assets having been transferred to over 40 million new shareholders. By 1996 an estimated half of Russia’s workers were employed in private firms—almost three times as many as in 1992.”67

However, the privatization of state-owned enterprises by issuing vouchers was controversial from the start, and only a small minority of Russian citizens benefited from it. The privatization program that the Supreme Soviet had passed in 1992 was structured to prevent corruption, but the program that Chubais implemented encouraged the accumulation of vouchers and property in a few hands and opened the door to widespread corruption. Sociologists Lynn D. Nelson and Irina Y. Kuzes, who have detailed the minute-to-minute proposals and politicking around privatization, explain:

The reformers did not want to openly discuss the actual objective behind their voucher distribution proposal, because they were telling the public one thing while pursuing an entirely different goal. Whereas at the time of the parliament’s June discussions Chubais had clearly stated, “The politics of the State Property Management Committee are not to further the stratification of society but to let everyone take part in people-oriented privatization,” the plan that [the] GKI had secretly developed was designed to have the opposite effect. And by November, Chubais was not hesitant to advance an entirely different interpretation of voucher privatization’s meaning for the Russian citizenry. Now he was not speaking about the “stratification of society,” but rather about personal freedom, freedom to cash in on vouchers rather than to participate in “people-oriented privatization.”68

Citizens could purchase shares in formerly state-owned companies by investing their vouchers directly at auctions or indirectly through unregulated voucher investment funds. Either way, managers retained control over most industries, investors wound up owning very little, and the average Russian struggled to survive amid economic hardship.69 Economist James Millar concludes that voucher privatization was “a de facto fraud.”70

Privatization was intended to spread the fruits of the free market. Instead, it helped to create a system of “tycoon capitalism” acting in the service of half a dozen corrupt oligarchs. The “reforms” were more about wealth confiscation than wealth creation; and the incentive system encouraged looting, asset stripping, and capital flight.71 E. Wayne Merry, former chief political analyst at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, observes that “We created a virtual open shop for thievery at a national level and for capital flight in terms of hundreds of billions of dollars, and the raping of natural resources.…”72

Moreover, as crime specialists Svetlana Glinkina73 and Louise Shelley74 point out, privatization was carried out with little concern for organized crime.75 Yet privatization processes shaped the distribution of wealth in Russian society as well as citizens’ perceptions of democracy and capitalism. Part of the public came to associate the terms “market economy,” “economic reform,” and “the West” with dubious activities that benefited only a few people while others experienced a devastating decline in their standard of living—a far cry from their secure lives under socialism.

Public sentiment against privatization was visceral: Russians came to call it the “great grab.” Distancing himself from Chubais’s policies and citing the corrupt nature of the governmental apparatus, Yeltsin derided “Chubais-style” privatization.76 In the December 1995 Duma election in Russia, communist parties won about one-third of the popular vote and 42 percent of the seats, a strong showing that was partly attributable to anti-privatization sentiment.77 Reform came under siege by citizens and parliamentarians, and activities of the Chubais Clan were placed under investigation by parliamentary bodies. As Russia scholar Peter Reddaway reports:

In 1997, the Duma voted by 288 to 6 to denounce the privatization program of 1992-1996 as “unsatisfactory.” According to the chairman of the Duma commission set up to examine the program, its results were “chaotic” and “criminal”: Although 57 percent of Russia’s firms were privatized, the state budget received only $3-5 billion for them, because they were sold at nominal prices to corrupt cliques.78

Chubais, one of the most hated public figures in Russia, was branded by millions of Russians as the architect of “grabitization”—the man who gave away the nation’s great factories and its vast wealth of natural resources at fire-sale prices. As the executor of privatization, he had strong links with some of Russia’s rising power groups and new rich, and many average people perceived him as an agent of the privileged. In 1997 nationwide public opinion polls, 70 percent of those surveyed said that Chubais’s privatization policies had a “bad” effect79—one that was linked to Harvard and America. At a 1998 symposium entitled “Investment Opportunities in Russia” at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, Yuri Luzhkov, the mayor of Moscow, made what might have seemed to many an impolite reference to his hosts. After castigating Chubais and his monetarist policies, Luzhkov, according to a report of the event, “singled out Harvard for the harm inflicted on the Russian economy by its advisers who encouraged Chubais’s misguided approach to privatization and monetarism.”80 Luzhkov said that “Harvard was in fact harmful to us by having proposed one of the models for privatization in Russia. Moreover this was a substantive harm.”81

DEMOCRACY BY DECREE

Beginning in 1992, Chubais acquired a broad portfolio, ranging from privatization and the restructuring of enterprises to legal reform, the development of capital markets, and the creation of a regulatory framework for business and securities transactions. A number of commissions dealing with bankruptcies, tax arrears, and debt were set up under Chubais, who also headed the GKI and in 1994 became first deputy prime minister. The creation of the Commission on Economic Reform in 1995 was further confirmation, as the Russian newspaper Kommersant-Daily states, that “a new center of economic power is being created around First Deputy Prime Minister Anatoly Chubais.” With “very great” powers, the commission was described as “a quasi-Council of Ministers … in direct competition with the bodies that have already been vested with such powers.”82 As sociologist Kryshtanovskaya summed it up, “Gradually, his [Chubais’s] men started controlling not just privatization, but also the anti-trust policy, the bankruptcy mechanism, taxes, relations with regions (including the organization of the gubernatorial elections) and what was called ‘the propaganda work’ in Soviet times.”83

Chubais’s program was so controversial that he ultimately had to rely largely on presidential decrees, the preferred method of many market reformers, for implementation. Members of the Chubais Clan bragged that, after the privatization program passed Russia’s parliament, “every subsequent major regulation of privatization was introduced by Presidential decree rather than parliamentary action.”84 And a 1996 presidential directive dictated that only Chubais (at the time Yeltsin’s chief of staff) had the authority to decide whether presidential decrees were ready to be signed—a directive that could be circumvented only upon receiving direct instructions from the president.85

Over the years, many aid officials embraced this dictatorial modus operandi and promoted presidential decree and the circumvention of parliamentary authority as a means of achieving market reform. Jonathan Hay and his associates actually drafted many of the Kremlin decrees. As USAID’s Walter Coles, a key American official in the privatization and economic restructuring program in Russia, pointed out, “If we needed a decree, Chubais didn’t have to go through the bureaucracy.” Further, with U.S. funding, Western public relations firms have engaged in “public education” to promote privatization. USAID spent $18.9 million on public education for mass privatization alone, including publicity around the voucher auction.86 Acknowledging the lack of political support for many “reform” measures, Coles said, “There was no way that reformers could go to the Duma [the parliament of the Russian Federation set up in 1993] for large amounts of money to move along reform.”87 They didn’t have to. U.S. assistance policies in Russia, like some of those in Central Europe, supported specific individuals and reforms at the expense of democratic processes and institutions.

Of course, the Russians themselves are primarily responsible for the manner in which reform was carried out. But by putting its reform portfolio in the hands of the Chubais Clan, USAID alienated other parties to the reform process who clearly had to be brought on board if legal and regulatory reforms were to be implemented. Without public support or understanding, decrees constitute a weak foundation on which to build a market economy. Some reforms, such as lifting price controls, may be achieved by decree. But many others, including those of privatization and economic restructuring, depend on changes in law, public administration, or mind-sets, and require cooperation across the full spectrum of legislative and market participants, not just a clan. Without support from parties to the reform process, reforms were almost certain to be ignored or even subverted during implementation.

A case in point was USAID’s showcase effort to reform Russia’s tax system and to set up clearing and settlement organizations (CSOs)—an essential ingredient in a sophisticated financial system. Those efforts failed largely because they were put solely into the hands of one group, which declined to work with other market participants. In Moscow, for example, despite millions of USAID dollars, many of the Russian brokers were excluded from the process and declined to use the Moscow CSO.88 Thus, since 1994, when consultants working under USAID contracts totaling $13.9 million set out to design and implement CSOs in five Russian cities, very little evidence of progress has emerged. The GAO’s report called the CSO effort “disappointing.”89

This did not surprise Charles Cadwell, a consultant working in Russia under USAID’s legal reform program. He explained that “to the extent you want to control relationships among firms and to affect the behavior of managers, that is the last thing that can be done by decree. Managers will continue to operate in the old ways until there are incentives to operate in new ones. You have got to have people on board.”90 Responsible USAID contractors working in Russia also felt compelled to address the issue of inclusion. As Cadwell put it, “Do you access and deal with local politicians and political realities, or do you bulldoze over them?”91

Indeed, some influential Russians complained of just that. Leonid Abalkin, director of the Institute of Economics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said that American aid was “given to Chubais” and that it was about “personal contacts.”92 Sergei V. Burkov, chairman of the Duma’s Committee for Property, Privatization, and Economic Activity, concurred that American aid supported one particular political group. The “process needs to be opened up,” he stated.93

It is easy to understand the donors’ impulse to support a “reformer” group. As the U.S. Department of State’s deputy aid coordinator (now coordinator) William B. Taylor explained, U.S. aid officials chose a narrow focus: “We have a limited amount of money. If you spread your money too thin, you probably won’t have as much of an effect. As [USAID Administrator] Brian Atwood has said, you can go [in] … as a sprinkler and spread out over a lawn or can go in as a firehose.”94 Of course, the strategic targeting and coordination of resources are critical. But USAID went further to sustain certain firemen. As USAID’s Coles proclaimed, “Reformers are the ones that are willing to take the risk. Their necks are on the line.”95

While this approach sounds good in principle, it is less convincing when put into practice because it is an inherently political decision thinly disguised as a technical matter. As Harvard-Chubais principals Andrei Shleifer and Maxim Boycko themselves acknowledged in an American book funded by the Harvard Institute96 and found on the desks of many USAID officials:

Aid can change the political equilibrium by explicitly helping free-market reformers to defeat their opponents.… Aid can help reformers by paying for the design and implementation of their projects, which gives them a greater capacity for action than their opponents have. Aid helps reform not because it directly helps the economy—it is simply too small for that—but because it helps the reformers in their political battles.97

In a 1997 interview, Ambassador Richard L. Morningstar, the Department of State’s top aid official, stood by this approach: “If we hadn’t been there to provide funding to Chubais, could we have won the battle to carry out privatization? Probably not. When you’re talking about a few hundred million dollars, you’re not going to change the country, but you can provide targeted assistance to help Chubais”98—an admission of direct interference in Russia’s political life.99

Shleifer and Boycko defined the goal of U.S. assistance to “alter the balance of power between reformers and their opponents” and confirmed that “United States assistance to the Russian privatization has shown how to do this effectively.”100 In answer to the question “Did USAID help propel Chubais into top positions in Russian government?” USAID Assistant Administrator Thomas A. Dine concurred with the “reformers”: “As an observer, I would say yes.”101 In other words, on its own terms, the firehose approach worked.

THE TWILIGHT ZONE OF FLEX ORGANIZATIONS

As the locus of reform shifted following the mass-privatization activities centered around the GKI, USAID set up a separate office for the Harvard Project and funded a network of private organizations run by the Harvard-Chubais transactors.

For many in the donor community, channeling money through private organizations was ideal, as that would circumvent inefficient and cumbersome bureaucracy. USAID’s Walter Coles acknowledged that the organizations were “set up as a way to get around the government bureaucracy.”102 But some “private” organizations created by USAID in Russia often carried out functions that ought to have been the province of the state. The organizations helped the transactors to bypass legitimate bodies of government, such as ministries and branch ministries relevant to the activities being performed, and to circumvent the democratically elected Duma. Indeed, the transactor-run organizations frequently carried out key functions of the state (for example, negotiating loans with international financial institutions, making and executing economic policy, and implementing legal reform).

The donors’ flagship organization was the “private,” Moscow-based Russian Privatization Center (RPC), which was held up by many in the aid community as a model for other aid-supported organizations. The RPC was established by Russian presidential decree in November 1992 under the direction of Chubais, who was chairman of its board even while head of the GKI.103 After reform activities expanded beyond the GKI, the RPC received its own aid-funded office in a separate building.

The RPC epitomized the operations of the aid-sustained Harvard-Chubais transactors. It was closely tied to Harvard in myriad ways, only one of which was characterized by a USAID-supplied explanation: that the Harvard Institute provided management support to the RPC.104 RPC documents state that Harvard University was both a “founder” and “Full Member of the [Russian Privatization] Center,” which was the “highest governing body of the RPC.”105 Harvard’s Shleifer served on the board of directors, along with Anders Åslund, a Washington-based former Swedish diplomat, long connected to Sachs and Shleifer. Åslund helped to deliver Swedish government monies to the RPC and served as a broker between the Chubais coterie and the governments of Sweden and the United States. Members of the Clan appointed one another to serve in the founding, governing, and management structure of the RPC;106 Chubais was chairman of the board; Maxim Boycko, managing director until July 1, 1996; Eduard Boure, managing director after July 1, 1996; and Dmitry Vasiliev, who also served as a vice chair of the GKI, deputy chairman of the board. Chubais, who recruited the RPCs board members, continued to serve on it even after Yeltsin dismissed him from government.107

The World Bank’s Ira Lieberman, a senior manager in the Private Sector Development Department, who helped design the RPC, said that it had “become a very convenient source for multidonor funding.”108 Setting up the RPC, USAID’s Coles said, “was a way … to get good people like Maxim Boycko … [and the] group of people that Chubais was managing that were sitting at the GKI.” Coles thought it was beneficial that setting up the RPC took ministries and branch ministries out of the policy process and gave the green light to an “independent body”—that is, Chubais, Boycko, Vasiliev, and the Harvard Institute. Such an “independent group being financed outside government structure could be hired and paid market rates.”109

With the Harvard Institute’s help, the RPC received some $45 million from USAID110 and millions of dollars more in grants from the EU, the governments of Japan111 and Germany, the British Know How Fund, and “many other governmental and non-governmental organizations,” according to the RPCs annual report.112 The RPC also received loans both from the World Bank ($59 million) and the EBRD ($43 million) to be repaid by the Russian people.113 A 1996 confidential report commissioned by the State Department’s Coordinator of U.S. Assistance to the NIS called the RPC “substantially over funded and largely ‘an instrument in search of a mission.’”114 The report also said that the RPC suffered from “‘imperial overstretch.’”115

In 1996, the World Bank committed a $90 million loan to support privatization and post-privatization activities, of which $59 million was to be managed by the RPC. The RPC was important in planning the loan, according to Lieberman. The World Bank picked up some of the overhead and operating costs that USAID previously covered.116 Despite Finance Minister Boris Fedorov’s opposition to at least some aspects of this loan,117 the World Bank (and the RPC) proceeded, and additional loans were negotiated.118

The largesse that flowed through the RPC appears to have been much greater than the sum total of all these figures would indicate. The RPC’s CEO and Chubais Clan principal Maxim Boycko has written that he managed some $4 billion dollars from the West while head of the RPC, according to Veniamin Sokolov, head of the Chamber of Accounts of the Russian Federation, Russia’s equivalent of the U.S. General Accounting Office. The Chamber has attempted to investigate how some of this money was spent. According to Sokolov, a report issued by the Chamber in May 1998 shows that the “money was not spent as designated. Donors paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for nothing … for something you can’t determine.”119

Formally and legally, the RPC was a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization. But the “private” RPC was funded by Russian presidential decree and received foreign aid funds because it was run by the St. Petersburg “reformers,” who occupied key positions in the Russian government. Was it, then, a government organization? Lending credibility to its identity as such, the RPC’s tasks included helping to make policy on inflation and other major macroeconomic issues, as well as negotiating loans with international financial institutions. Even more convincing was the fact that the RPC had more control than the GKI over some secret privatization documents and directives, according to the Chamber of Accounts. Two RPC officials were authorized to sign privatization decisions (Boycko and the American Jonathan Hay).120 So a Russian and an American—both representing a private entity—were approving major privatization decisions on behalf of the Russian Federation.

This blurring of the RPCs identity led to confusion among aid officials. USAID’s Dine said that he thought USAID saw the RPC as a government organization but that he had “never considered” the question. Dine added that “Maxim [Boycko] was a government employee [when heading up the RPC].”121 All the while asserting its nongovernmental status, the RPC was treated by USAID as a government ministry when U.S. assistance authorities asked it to nominate one person to serve on a technical evaluation panel to select a contractor.122 According to USAID contracts officer Stanley R. Nevin, USAID normally chooses this representative from a recipient government ministry, not from private bodies.123

The World Bank’s treatment of the RPC provides yet another example of its ambiguous status. The Bank’s funding of the not-for-profit, nongovernmental RPC was unusual in that the Bank typically negotiates with governments. In this case, repayment was to be made by the Ministry of Finance, the official borrower for the Russian government, while the RPC served as the implementing agency.124 The Bank’s Lieberman maintained that “we [the Bank] didn’t give [the loan] to [the RPC] as a private organization but as an agent for the government of Russia … the government of Russia is responsible for paying it back.”125 However, as a Russian representative to an international financial institution observed, “the same people who approve the loans use the money. This is what I don’t like about it.”

Concerned about conflicts of interest and questions of accountability, donors created the trappings of independent institutions. The RPC, for example, was set up with much of the usual Western apparatus of bona fide nonprofit organizations and even employed some Western administrators paid by donors. As a U.S. aid official in Moscow put it: “The RPC may be private but certainly looks political, just as the Heritage Foundation may be private but certainly supports a political constituency. The average Russian doesn’t make that distinction.”

The network of Local Privatization Centers, or LPCs, outside Moscow under the umbrella of the Moscow RPC illustrates this point. The LPCs were supposed to develop restructuring plans for enterprises and advise local governments on policy questions. With Western aid concentrated in Moscow, donors endorsed aid to the provinces. By 1996, ten LPCs had been set up, each with about 12 employees and one or two satellite offices with several employees.126 Three aid-paid consulting firms—Price Waterhouse, Arthur Andersen, and Carana—were charged with setting up the LPCs, two or three each. Representatives of all three reported that the LPCs, far from serving development, instead were steeped in political considerations, and they questioned the degree to which the LPCs were designed for sustainability.127

The idea of channeling technical resources beyond Moscow and setting up centers to help do so sounded promising. However, with aid as a political resource for the Chubais Clan and local leaders accustomed to looking to Moscow for favors, the Moscow RPC used its network of LPCs for its own political purposes.128 Dennis Mitchem, a former partner at Arthur Andersen, reported that “many things revolved around political considerations. I was told by Victor Pankrashchenko [deputy director at RPC] that, for political reasons, our center in Novosibirsk would not be opened.”129 Thus, although Arthur Andersen was supposed to set up four LPCs, it was allowed to set up only three.

The USAID-funded RPC replicated Moscow’s central authority in the patron-client tradition of Soviet society with regard to how central authority and local elites treated each other. Under that system, the careers of regional elites depended on high communist patrons in Moscow, and access and invitations to Moscow depended on the whim of high party officials there. Following that practice, Maxim Boycko, the RPCs managing director at the time, handpicked the directors and deputy directors of the regional centers, according to the consultants who helped to set up the LPCs and a USAID official in Moscow handling them.130 Mitchem noted that “there were political reasons behind appointments” and that “some appointments were purely political.”131

LPC leaders were rewarded for loyalty, even if that involved doing little or nothing, and sometimes even were reprimanded for local reform initiatives. Mitchem said that it was disconcerting to contractors that “we had some strong talents, and we made it clear to the RPC and AID that we wanted to use our talents,” but were often stymied. He also said that the LPC directors were concerned mainly with pleasing the RPC: “They did what Maxim [Boycko] wanted. Maybe the RPC didn’t want to accomplish anything.”132

Robert Otto of Carana, who set up the rest of the LPCs, likewise stated that local directors were “inclined to do whatever Moscow told them to do. The central office defines the rules of the road. From the start it was clear that the RPC wanted the LPCs to facilitate the RPC’s agenda.” Otto recounted that “the only thing that mattered to the RPC was that the LPCs did what [the RPC] wanted doing.… The LPC people slid very easily into that because it was normal for them to get orders from Moscow.”133

Under all these circumstances, were useful activities with a potentially lasting impact being accomplished? The RPC received so much money largely because of the Western clout of “reformers” Chubais and Boycko. Was an organization dependent on the clout of these two men able to spawn sustainable institutions? After a 1996 investigation into the Harvard Institute’s activities in Russia, the GAO concluded that “the RPC’s sustainability is in question once USAID assistance ends in 1997.”134

In the autumn of 1994, Harvard made another institutional push by creating several more aid-funded “private” institutions. One was the Russian Federal Commission on Securities and the Capital Market, or the Federal Securities Commission, a rough equivalent of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (also known by Americans as the “Russian SEC”). The Federal Securities Commission was founded by Russian presidential decree and run by Chubais Clan member Dmitry Vasiliev, who served as executive director and vice chairman of the board, while Chubais served as chairman. The commission had very limited enforcement powers and Russian funding, but USAID supplied funds through two Harvard-created and -funded organizations run by Jonathan Hay, Vasiliev, and other members of the Harvard-Chubais coterie.

One organization was the Institute for Law-Based Economy (ILBE), funded both by the World Bank and USAID. ILBE was set up to help develop a legal and regulatory framework for markets and evolved to entail drafting decrees for the Russian government. It received nearly $20 million from USAID. Like the RPC, one of ILBE’s founding partners was the “President and Fellows of Harvard University.”135 The 1996 confidential State Department report referred to earlier suggests that Harvard was involved in ILBE’s activities. The report states that, according to the Harvard Institute, ILBE’s “founders are expected to provide political support for the activities of the ILBE.”136

It is logical that this state of affairs led to abuse. In particular, key transactors obstructed reform when such initiatives originated outside their own group or when the initiatives were perceived as conflicting with the agendas of their group.137 When a USAID-funded organization run by the Chubais-Harvard transactors failed to receive the additional USAID funds they had expected, they promptly blocked legal reform activities in the areas of title registration and mortgages—programs that were launched by agencies of the Russian government.138 In such instances, the transactors’ interference put them at cross purposes with their own purported aim of fostering markets.

Despite persistent reports of such abuse, U.S. officials for many months defended and supported the Harvard-Chubais group, though from the beginning USAID had failed to monitor the group adequately, as indicated by the GAO’s 1996 finding that USAID’s management and oversight of the Harvard Institute was “lax.” When, in 1997, USAID’s inspector received disturbing documents and began investigating the Harvard Institute, the laundry list of alleged misconduct included investments in the lucrative Russian securities markets and other “activities for personal gain.”139 For example, the U.S. government suit against Harvard University and four American transactors in September 2000 alleged that “Shleifer, [Nancy] Zimmerman [Shleifer’s wife], and Hay purchased several hundred thousand dollars worth of shares in Russian oil companies, and concealed the ownership of those shares by using the name of Shleifer’s father-in-law.” Hay has been named in another investigation, as well.140

Hay allegedly also used his influence, as well as USAID-financed resources, to help his girlfriend (now wife), Elizabeth Hebert, set up Pallada Asset Management, a mutual fund, in Russia, according to government sources. A third transactor, Sergei Shishkin, appeared as needed, once as the head of ILBE, sometimes as the director of five Russian companies, among them Pallada. After U.S. investigators noticed this, new Pallada documents materialized without Shishkin’s name. Pallada became the first mutual fund to be licensed by Vasiliev’s Federal Securities Commission. Vasiliev approved Pallada ahead of both Credit Suisse First Boston and Pioneer First Voucher, much larger and more established financial institutions.141 Moreover, as reported in Russia, Vasiliev’s commission entrusted Pallada—without a competitive tender and with funding from the World Bank’s Investment Protection Fund—with management of a government fund to compensate victims of equities fraud. Russia’s Accounting Chamber reported that an investigation had revealed that not a single kopeck had been paid to a defrauded investor in the first year and a half of the fund’s existence, though the fund’s Western consultants had been receiving their salaries.142

As the flow of Western aid diminished, Hay, Shleifer, and Vasiliev looked to keep their activities going. Using ILBE resources and funding, they established a private consulting firm, ILBE Consulting, with taxpayer money. One of the firm’s first clients was Shleifer’s wife, Nancy Zimmerman, who operated a Boston-based hedge fund that traded heavily in Russian bonds. According to Russian registration documents, Zimmerman’s company set up a Russian firm with Sergei Shishkin, the ILBE chief, as general director. Corporate documents on file in Moscow showed that the address and phone number of the company and ILBE were the same.143

In August 1997, ILBE’s Russian directors were caught removing $500,000 worth of U.S. office equipment from the organization’s Moscow office.144 The equipment was returned only after weeks of U.S. pressure. When auditors from the USAID’s inspector general’s office sought records and documents regarding ILBE’s operations, the organization refused to turn them over, and the auditors left emptyhanded.145

Thus the transactor-created, aid-funded “flex organizations”—so-called in recognition of their impressively adaptable, chameleon-like, multipurpose character—played multiple and conflicting roles: They could switch their status and identity as situations dictated. They sat somewhere between state and private, between the Russian government and Western donors, and between Western and Russian allegiance and orientation. They were sometimes private, sometimes state,146 sometimes pro-Western, sometimes pro-Russian. Whatever their predilection at a given moment, the organizations were run by the Chubais-Harvard transactors (with financial support from USAID through Harvard and U.S. contractors)147 and served as the transactors’ domain and political and financial resource.

Flex organizations were also compatible with the Russian cultural context, in which control and influence, not ownership, were pivotal.148 They mimicked the dual system under communism, in which many state organizations had counterpart Communist Party organizations that wielded the prevailing influence. And they may have facilitated the development of what the author has called the “clan-state,” a state captured by unauthorized groups and characterized by pervasive corruption.149 E. Wayne Merry, the former U.S. senior political officer, regretted the U.S.-sponsored creation of “extra-constitutional institutions to end-run the legislature.” He added that “many people in Moscow were comfortable with this, because it looked like the old communistic structure. It was just like home.”150

TRANSIDENTITIES

Not only could transactor-run organizations switch status and identity according to the situation, so could some individual transactors. Key Harvard-Chubais transactors could change their national identity back and forth as convenient: sometimes as American representatives, sometimes as Russian ones, regardless of which side they came from. To suit the transactors’ purposes, the same individual could represent the United States in one meeting and Russia in the next—and perhaps himself at a third—regardless of national origin. Such “transidentity capabilities”151—this ability of an individual to shift his identity at will, irrespective of which side originally designated him as a representative—lent yet another source of flexibility and influence to the transactors.

A significant example is that of the Harvard Institute’s Russia project general director Jonathan Hay. Hay’s transidentity was institutionalized by policies and procedures on both sides. Formally a representative of the United States, Hay interchangeably acted as an American and a Russian. As an American, Hay not only acted as Harvard’s chief representative in Russia, but also exercised formal management authority over other U.S. contractors, which the U.S. government had granted to the Harvard Institute under a cooperative agreement. In addition to being one of the most influential foreign consultants in Russia, Hay was also appointed by members of the Chubais Clan to be a Russian. As a Russian, Hay was empowered to sign off on pivotal, high-level privatization decisions of the Russian government.152 According to a U.S. official investigating Harvard’s activities, Hay “played more Russian than American.”

Another example of transidentities is that of Julia Zagachin, an associate of Hay’s. Zagachin, an American citizen married to a Russian who was chosen by Chubais Clan principal Dmitry Vasiliev, head of the Russian Federal Securities Commission, to assume a position designated for a Russian citizen. Zagachin was to run the First Russian Specialized Depository, which holds the records of mutual fund investors’ holdings and was funded by a 1996 World Bank loan. As journalist Anne Williamson, who specializes in Soviet and Russian affairs, has reported, the World Bank had established that the head of the Depository was to be a Russian citizen. But Vasiliev and other members of the Clan apparently had determined that if their associate Zagachin headed the Depository, they would retain greater control over its assets and functions, so as to evade accountability if necessary.153 The financial arena yields many such examples of transidentity, in which Chubais transactors appointed Americans to act as Russians.

It was (and is) difficult to glean exactly who at any given time prominent consultants on the international circuit represented, for whom they actually worked, all sources of funds, and where their ambitions lay. Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs, who served as director of the Harvard Institute from 1995 to 1999, and conducted advisory projects in the region, in the early 1990s sometimes under the umbrella of Jeffrey D. Sachs and Associates, Inc.,154 provides a case in point.155 According to journalist John Helmer, Sachs and his associates (including David Lipton, who later went to Treasury with Lawrence Summers) played both the Russian and the IMF sides. During negotiations in 1992 between the IMF and the Russian government, Sachs and associates appeared as advisers to the Russian side.156 However, Helmer writes that “they played both sides, writing secret memoranda advising the IMF negotiators as well.”157

Adding to the ambiguity was the question of whether Sachs was an official adviser to the Russian government. Although he maintains that he was158—and he certainly was often portrayed as such in the West—some key Russian economists as well as international and American officials have suggested otherwise.159 Jean Foglizzo, the IMF’s first Moscow resident representative, was taken aback by Sachs’s practice of introducing himself as an adviser to the Russian government. As Foglizzo told Williamson, “[When] the prime minister [Viktor Chernomyrdin], who is the head of government, says ‘I never requested Mr. Sachs to advise me’—it triggers an unpleasant feeling, meaning, who is he?”160

Whatever ambiguity surrounded Sachs in terms of whom he represented at a given time, his role as an intermediary and promoter seemed clear. In 1992, when Yegor Gaidar (with whom Sachs had been working) was under attack and his future looked precarious, Sachs offered his services to Gaidar’s parliamentary opposition. In November 1992, Sachs wrote a memorandum to the chairman of the Supreme Soviet, Ruslan Khasbulatov (whose reputation in the West was that of a retrograde communist), offering advice, Western aid, and contacts with the U.S. Congress. (Khasbulatov declined Sachs’s help after circulating the memo.)161 Sachs was also adept at lobbying American policymakers, as indicated, for example, in U.S. State Department memoranda.162 And he was visible in a promotional role in Russia, holding press conferences to explain, justify, and advocate the economic policies of the Russian government to the Russian public.

An associate of Sachs’s and another ubiquitous transactor was Anders Åslund, the former Swedish envoy to Russia. Åslund was connected to Chubais and the Clan even before the dacha days. Based in Washington, he worked with Sachs and Yegor Gaidar. Like the grants Sachs secured, those that Åslund received from several sources were substantial.163 He played a key role in promoting the Chubais group. Åslund appeared to represent and to speak on behalf of American, Russian, and Swedish governments and authorities. He was seen by some Russian officials in Washington as Chubais’s personal envoy, and is known to have played a role in Swedish aid and policy toward Russia, as stated earlier. (For example, Åslund was highly influential with Sweden’s Prime Minister Carl Bildt, who promoted him in Washington and included him in a high-level official delegation to the White House.164) Although a private citizen of Sweden, he participated in high-level, closed meetings shaping U.S. and IMF policies toward Russia in the Departments of Treasury, State, and USAID.165

Åslund was also involved in brokering business activities in Russia.166 He had “significant” business investments there, according to Vyacheslav Razinkin, head of the Interior Ministry’s Department of Organized Crime.167 In addition to (or perhaps as part of) his work for the Chubais Clan, governments and business, Åslund was paid to do public relations. His assignment in Ukraine, where he also was active and funded by George Soros’s Open Societies Institute, explicitly included public relations on behalf of Ukraine, according to Soros-funded advisers who worked with Åslund in Russia and Ukraine.168 Åslund’s effectiveness in this role no doubt was enhanced by his affiliation with Washington think tanks, his frequent contributions on Russia and Ukraine to publications such as the Washington Post and the London Financial Times, and the fact that he was invariably presented as an objective analyst, despite the promotional roles he additionally played.169

Clearly, the most effective transactors are the ones most skilled at exploiting fragmentation and amorphous structure: flex organizations, bureaucracy, and governments. The transactors have multiple roles and identities at their disposal and are adept at working them.

ORCHESTRATED MUSICAL CHAIRS

The Chubais-Harvard transactors’ near monopoly on aid in support of market reform, which they often realized through decree and “private” organizations used as political machines, made it easy for their representatives to actively pursue their own interests and to work on all sides of the table both in Russia and with the donors. The transactors worked through the donor community to influence aid policies toward Russia, to direct the allocation of technical assistance grants, and then to manage the monies themselves. Chubais signed letters requesting foreign aid while he and his associates were also the recipients of the aid.

With the backing of the United States, other donor nations, and the international financial institutions, the Chubais Clan and the Harvard Institute group were loyal and mutually dependent. Each was the other one’s entree. The Clan was Harvard’s avenue to Russia, key to its ability to claim clout and contacts with the Russian government. In turn, Harvard was the Clan’s channel to U.S. policymakers and aid dollars, although members of the Chubais group learned to cultivate their own contacts and subsequently often spoke on their own. Jonathan Hay often spoke on behalf of Maxim Boycko, Dmitry Vasiliev, and other Chubais Clan members.170