A Few Good Financiers: Wall Street Bankers and Biznesmeni

It’s typical of every fund that they set out to do something with small and medium sized enterprises and then it became clear that it’s not so easy.

—Marek Kozak, head of an aid-funded program to foster business development in Poland1

IF DONORS CONFRONTED A TRADE OFF between the latitude they conferred upon consultants and recipients to design and implement aid programs and their own control and oversight of these programs (as seen in the types of aid discussed in chapters 2 through 4), there was equally a balance to be struck in yet another area of aid to the Second World: assisting private business in diverse and rapidly changing business environments.

The disintegrating Eastern Bloc ushered in a new era of what the Poles called biznes—mom-and-pop service industries and traders hawking everything from bananas to computers. An important stated goal for Western donors—and a key to creating competitive markets—was to provide support for new small and medium-sized businesses and especially to help foster stronger, more highly developed business sectors as a prerequisite to the development of a market economy and democracy.

In lending support to this sector, donors employed a combination of aid approaches—sending Western consultants and funding indigenous groups—described in chapters 2 through 4. The consultants were loan officers or advisors on such issues as how to write a business plan; the groups were newly emerging “businesses”—often family members or partners of previous acquaintance.

Like the privatization of state-owned companies, the creation of a new business sector carried symbolic weight for the donors. Under socialism, business had been either heavily restricted, or, as in the Soviet Union, totally outlawed and pushed into an underground economy. The creation of a flourishing business sector was an integral part of entombing the socialist state and creating a capitalist one.

However, Central and Eastern Europe was a diverse landscape of fluctuating business conditions and of changing politics and domestic and external economic constraints. It would be very difficult to strike a balance between incorporating knowledge of local business practices, conditions, and needs of a given time and place and imposing donor standards and oversight.

FAMILY BUSINESS

Just what was the “private sector” in Central Europe circa 1990, and in what fields could foreign aid programs play a useful role? This question could not be answered once and for all: given that biznes practices and conditions varied considerably over time and place, there were differences in the need and demand for any kind of business support. In the immediate post-1989 aftermath in Central Europe, new opportunities for trade seemed to open up for a few weeks or months, only to close again. Legal infrastructure and enforcement and financial terms were in flux.

The communist legacies that shaped the emergent business sectors, and the effects of those legacies on further development, however, were steady. Part of the private sector was comprised of formerly state-owned companies that private people—often former nomenklatura managers—had simply “made one’s own.” Put another way, these companies had been “privatized” by virtue of state managers having acquired them. (See chapter 2 for discussion of the privatization of state-owned enterprises.) The other, more dynamic, part of the private sector consisted of new business.

In Poland under communism in the 1980s, the legal private sector—which included much of agriculture, construction, small shops, restaurants, handicrafts, and taxis—was the largest in the region. It generated nearly one-fifth of the national income and employed nearly one-third of the work force in the early 1980s.2 Despite the considerable risks entrepreneurs still had to assume to operate in 1990, the number of businesses increased from 805,879 on January 1, 1990, to 1,028,484 on August 8, 1990.3 Such activity was grounded primarily in trading, not acquisition of state resources and property.

Throughout the 1990s, Poland saw an explosion of new businesses. Most of these were domestic or household enterprises: in 1992, the average number of employees in new businesses was 1.7, including owners, according to a World Bank study.4

The family as a unit of business was not a new invention. Under the informal economies that flourished with communism, the family was the focus of work and consumption and the starting point for the exchange of information, which at that time was critical to the success of many activities. The family was the survival unit of pooled scarce goods and services.5 Trust was essential in informal economies: it simply did not make sense in most cases to hire outside of one’s social circle. Although such behavior may appear irrational to outsiders, family relationships facilitated certain understandings that did not require legal contracts. Being outside on one’s own—without networks—was like being on a sinking ship without a life jacket. Both trust and the use of family networks figured prominently in the evolution of biznes in the 1990s.

The idea of formal labor markets—in which employers advertise jobs and people apply for them—was problematic when applied to Central and Eastern Europe. Polish employers of new businesses, for example, seldom hired in a meritocratic way; instead, they chose workers from the ranks of those already in their networks. Someone working at the university would receive a call from a member of his social circle now in public office who was “looking for someone from our circle” to head up a project in the government civil service. A study by sociologist Barbara Heyns found that the use of such friendship and family networks to find jobs persisted even when factors that typically predicted employment in the private sector (such as being male, young, urban, and educated) were taken into account,6 although, in Central Europe, the trend, at least among some groups and the younger generation, appears to be toward professionalization and the adaptation of Western “professional standards.”

Another important dynamic of the emergent private sector (and one that casts doubt on some Western models) involved the relationship of two spheres of activity and employment: state and private. Some economists studying household strategies tended to assume that the two spheres were separate and distinct.7 Yet, in reality, they may not be so easily separable. Household strategies and patterns defied the neat ideological categories of planned versus market economy and state versus private sector.

In fact, some evidence suggests that families throughout the region tended to pursue diversified choices.8 In a common pattern, one member of the family would be employed in the more stable state sector while another would work in the private sector, which provided more opportunities but at greater risk. In Tula, Russia, men worked at reduced salaries in munitions factories, the main industry in a city with a population of about 600,000, while their wives traveled to Moscow to buy goods to sell in the Tula bazaars. When trading became too risky, families could fall back on the low but reliable salaries and benefits provided by state jobs, which included “side earnings”—trading or additional work opportunities available by virtue of the job. This was an insurance strategy: families pursued reasonable options in the context of the constraints and the enabling features of their environment. Their behavior was logical, not ideological.

It was also typical throughout the region, especially among certain groups, for a member or members of the family to work in both the state and private sectors. In Central Europe, as well as in Russia and Ukraine, many scholars on leave from the academies of science (which continued to provide long-term guarantees and some benefits) also were employed by Western-funded organizations. Many people with their own private consulting firms kept one foot in the government sector, thus staying on government payrolls. In Central Europe circa 1990-91 (but rarely much later) as well as further east quite consistently, visitors who interviewed officials in their official capacities frequently were offered “private” business cards from the officials’ side businesses, which sometimes had business dealings with the ministries for which they worked. This indicated that the host officials were looking for other opportunities. Such other opportunities would introduce, by many Western standards, a “conflict of interest” or potential conflict of interest with their government jobs. However, one of the few advantages of working at low-wage civil-service jobs was the opportunity for Western contacts and contracts that the jobs sometimes could provide. Thus, someone from the region might see a fringe benefit where an outsider saw a conflict of interest. One government official in Kiev gave the author three business cards: two for his own private consulting firms and one for his state job as an adviser to the president.

These 1990s relationships between “private” biznes activities and “state” sectors were deeply rooted in socialism. Given that such patterns were likely to continue to influence business development, what were the needs of the evolving business sectors, and where could foreign aid programs play a useful role?

PROGRAMS

The United States was among the first of the donors to begin to find out. Authorized under the SEED Act in 1989,9 the U.S. Enterprise Funds were designed to promote the development of Central and Eastern European private sectors, including loans, equity investments, grants, technical assistance, and joint ventures. Although the SEED legislation provided an overall framework for the funds, it allowed them substantial latitude in how they actually would operate.10 This portfolio was deemed so important that the $240 million authorized for the Polish-American Enterprise Fund and the $60 million for the Hungarian-American Enterprise Fund—the first to get under way in 1990—consumed a substantial portion of the initial U.S. aid package.11 Enterprise Funds accounted for some 28 percent of the SEED assistance for the region between fiscal years 1990 and 1993.12 The funds received considerable publicity, both at home and in the recipient countries. A USAID-commissioned evaluation affirms that “The funds became one of the most visible manifestations of the U.S. pledge to support the transformation.”13

From the perspective of the aid community, the hallmark of the funds was their independence of operation and the limited government oversight to which they were subject. As originally structured, they were accountable only to their boards of directors. In 1993, however, Congress charged USAID with greater oversight responsibility but maintained USAID’s very limited approval authority over program decisions.14 With little competition from other donors for loans or grants to support Central and Eastern European business, the Enterprise Funds were seen by many as a premier assistance program, and one that constituted a new kind of public-private partnership: a less-regulated type of foreign aid that would encourage private enterprise mainly through loans and direct investments rather than traditional grants. The management of the Polish-American Enterprise Fund described it as a “bold experiment—a new way for the U.S. government to deliver economic assistance to Poland, tapping into private sector expertise unencumbered by the bureaucratic constraints normally associated with governmental organizations.”15 The funds often were cited as an aid “success story” and held up by the U.S. Congress and critics of traditional aid programs as a template for future aid. In 1995, the funds had disbursed nearly $270 million in investments to 3,305 companies. By 2000, the funds had obligated more than $1 billion to 18 countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.16

The often slow, bureaucracy-laden EU, which, in contrast to the United States, channeled its aid to governments, was not prepared to start up a substantial business-aid program so quickly. However, in time, the EU’s PHARE program introduced an innovative concept conceived by Polish specialists. Beginning in 1993, as the EU broadened its portfolio to include small- and medium-sized enterprises and infrastructure support, it launched the “Struder” program for development in selected regions of Poland. Largely designed by Poles with EU support, Struder was administered by the Polish Agency for Regional Development, a government agency established in 1993 to support regional development. Struder was to spur development in six (later, under Struder II, fourteen) voivodships (provinces) that suffered from the costs of economic restructuring but were deemed to have significant growth potential. The program provided grants, equity capital, guarantees, training, and advisory services in an effort to stimulate profitable investments and infrastructure development.17 By the end of 1997, when Struder was phased out, the EU had provided 76.7 million ECU (about $85 million18) to the program. Other small EU-funded programs followed (primarily for infrastructure, with limited resources available for technical assistance and training), bringing the figure up to more than 100 million ECU in 2000.19 However, largely a local invention, Struder never expanded into other countries.

Other donors and programs also launched business-development programs: a host of mostly small initiatives, such as microcredit lending, was funded by Western foundations, governments, or some combination thereof. Still, the U.S. Enterprise Funds were held up as a model, especially among some European donors that worked solely through governments and felt constrained by that practice. The funds were relatively unencumbered by government regulation on the donor side, and, in some recipient countries, on the recipient side as well. One independent evaluation of the funds noted that “Other donor agencies in the region were envious of the speed with which the funds became operational, and the flexibility and independence allowed in the programs.”20

Yet nearly all business-support programs faced daily dilemmas that reflected a larger trade-off: to what extent to impose donor standards of paper trails and accountability and to what extent to take into account the knowledge and business conditions of the hosts.

MISSION AND MOTIVATIONS

The U.S. Enterprise Funds appear to have had differing answers to that question, depending largely on the context in which a specific fund was operating and the leadership of that fund. The major challenge facing the Enterprise Funds was an inherent conflict between “aid” and “business” orientations—an identity crisis typical of some development banks. Should they support risky business activities that could produce big results or less risky activities that would demonstrate “success,” especially to the U.S. Congress? And was their mission to give aid liberally or to make sound business decisions using stringent Western loan criteria? And so this fundamental—and probably unavoidable—dilemma enveloped their mission: were they in the aid business or were they in business?

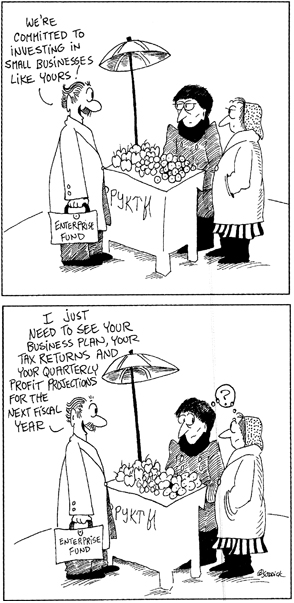

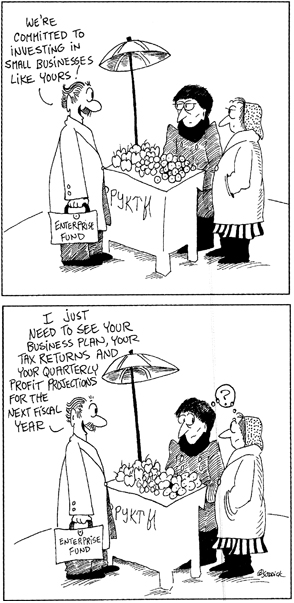

The question arose forcefully in Central Europe where the Enterprise Funds got off to a rough start. Central Europeans often were introduced to the Enterprise Funds through publicity surrounding the visits of President George Bush and other American dignitaries who announced their launch. The Enterprise Funds fell into the rhapsodic phase of Triumphalism. A USAID-commissioned report notes that

The funds became one of the most visible manifestations of the U.S. pledge to support the transformation. As such, they have brought considerable political good-will to the United States.21

However, the phase of Disillusionment was not far behind. The same report goes on to say that

this political dimension created two serious problems. First the announcement of the funds created an avalanche of requests for money from would-be business owners, putting a great strain on the funds during their start-up phase. Second, there was a great deal of disappointment and negative publicity in the countries when people discovered that the funds were requiring repayment of the capital with interest.22

Indeed, the high profile of the Enterprise Funds helped to raise peoples’ expectations—expectations that were greatly out-of-step with the funds’ possibilities for delivery. In the first weeks and months following the launching of a fund, the local offices—which often at the time had only skeleton staffs—received hundreds of applications, which often were little more than handwritten requests for money. The Polish Fund, for example, was announced before it was up and running, creating a huge backlog of applications that led to frustration and resentment.23

Greatly contributing to the problem was the fact that Central and Eastern Europeans generally had little background for understanding just what fund managers expected by way of documentation and collateral. They had scant understanding of the necessity of a business plan, let alone how to put one together. Further, there had been little clarification explaining that the funds would not be disbursed in the form of grants, but were loans that had to be repaid—and with interest. Former Czechoslovak aid coordinator Zdeněk Drábek said that people had understood that the funds would consist of grants to small businesses. “[There was] a lot of disappointment,” he said, “when they [people] discovered that money was not to be given away freely.”24

There was also a perception among some recipient officials that the needs of Central and Eastern European business were not necessarily foremost among the concerns of the Enterprise Fund managers. Each fund was a private, nonprofit corporation. Boards were headed by prominent financiers and venture capitalists, and board members, such as AFL-CIO president Lane Kirkland and former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, donated their time. The funds embarked on a three-pronged investment strategy: (1) direct investments involving equity or debt-equity combinations to joint ventures or privatized enterprises; (2) joint bank lending programs designed to direct credit in the range of $20,000 to $200,000 to small businesses; and (3) small-loan programs for small businesses and lending programs to specific industries.25

Funds operating in Central Europe generally took a conservative approach to lending money, to achieve the goal of self-sufficiency. They did not dispense monies easily or quickly, requiring loan applicants to produce much of the same kind of financial documentation that typically was required for loans in the United States. For most businesspeople in the former communist countries this was nearly impossible at least in the immediate postcommunist aftermath: they lacked a paper trail and credit track record (audited financial statements and tax returns were typically unavailable) and were unaccustomed to Western loan-application procedures. Further, as the managing director of the Hungarian-American Enterprise Fund, Charles Huebner, related, given their lack of such experience under communism, Hungarians had little sense of obligation to pay back loans. As stealing from the state had been a key survival strategy under communism, why should repaying a banking institution be expected?26 However, within a few years Central European businessmen had generally become familiar with acceptable Western business practices.

More often than not, Enterprise Fund managers opted to devote their efforts not to the small businesses requiring just a little capital that typified the region, but to big, visible deals and joint ventures that promised rewards in prestige and cash. Joint ventures, which the SEED legislation listed as an option,27 were easy to create, lucrative, yielded incentive funds for the partners, and looked good to Congress because they helped U.S. business—even though smaller, indigenous businesses were the ostensible primary targets of the funds’ attentions.

The Polish Fund was known for its profits. To bypass the $150,000-a-year salary ceiling for fund officers set by Congress, some officers devised enterprising ways to augment their salaries. In Poland, fund managers created a “clone,” the Polish Private Equity Fund, which was financed partly by foreign private investments and partly by the original Enterprise Fund. Unlike the Enterprise Fund, a share of the profits of the Equity Fund went to the managers. It made both equity and loan investments but did not take part in the fund’s small loans program, high-risk agricultural investments, or join in technical assistance efforts.28 Fund managers also discovered that one way of getting in on potentially lucrative deals was to enlist the help of former Polish government operatives. By 1994, the fund resembled a Washington revolving door, with several former high privatization officials having been hired to manage fund portfolios. The Polish Fund, unlike others in Central Europe, maintained costly executive and investment offices in the United States.29

Similarly, the Hungarian-American Enterprise Fund set up, and invested $4 million in an investment services company, nearly all of its paid-in capital, which earned some of its partners twice (or higher) the fund’s salary ceiling. This deal violated fund policies, which restricted investments to $3 million and required substantial contributions by coinvestors.30 In addition to questions about the salaries of fund partners and staff, the GAO found cases of potential conflicts of interest or the appearance thereof. For example, a Polish fund director served as president of a fund-supported foundation, as well as a professor at the university where the foundation was established. He was paid for serving in all three capacities at the same time.31

All this led to criticism that the funds, being too risk averse, failed to fulfill their primary mission of supporting small and medium-sized indigenous businesses.32 As Henryka Bochniarz, a former Polish privatization official (not working for the fund) charged: “They [the funds] want to have very good investments without headaches.… They behave like a demanding commercial institution.… This was not the idea of the Enterprise Funds.… When you talk to the [fund] people, you have the feeling that the windows program [of small loans] is totally not important.… But from the point of view of Polish society, the windows program was very important.”33

Similar views were expressed elsewhere in Central Europe. Zdeněk Drábek, former aid coordinator of Czechoslovakia, said, “The idea was that it [the fund] would go to small firms.… The reality was that it went to finance companies that had 500 to 1,000 employees.”34 When the Hungarian Fund invested in companies that had access to other sources of capital (representing 12 percent of its invested capital), the GAO questioned “whether such investments were consistent with the fund’s mandate to develop small- and medium-size businesses.” Hungarian Fund officials countered with trickle-down economics, asserting that these investments in publicly traded companies “leveraged additional investment capital by (1) encouraging other investors to invest and (2) helping to stabilize the stock market, which was not very efficient in pricing stock offerings.” Fund officials added that the investments helped to balance the portfolio and enabled the fund to invest in other, riskier businesses.35 But Zbigniew Brzezinski, a member of a board of the Polish Fund, seconded the judgment of GAO, remarking, “These funds should promote native private enterprises. They were not set up to establish foreign private investment.”36 However, compared with the development banks operating in the region, the Enterprise Funds maintained a favorable track record, as reported in a USAID-commissioned evaluation:

Enterprise funds are helping to broaden access to capital for entrepreneurs by investing in enterprises that have few alternatives. The funds have invested more than $267 million, a high percentage of which has gone to small and medium-sized enterprises. Enterprise funds are more effective at providing capital to private businesses than are other international organizations such as EBRD, World Bank, and EC Phare. Nevertheless, even under the best of circumstances, enterprise funds are able to help only a small percentage of the newly emerging private enterprises in the region.37

And, with such a large gap between the expectations created and the ultimate results, the fact that the funds failed to concentrate on small targets was not lost on the recipients, especially given the publicity the funds had generated in the host countries. As Bochniarz reported, “Today [the Polish Fund is] one of many financial institutions coming here and trying to make money. Nobody considers this part of American aid.”38

The Polish Fund’s profitability eventually created a dilemma: What to do with some $300 million (generated by fund loans and investments) left over when the fund declared its mission fulfilled and went out of business? After some controversy,39 it was decided in 1999 that $120 million would be returned to the U.S. Treasury, while the remainder would be used to set up the Polish American Freedom Foundation.40 The foundation has begun its work by subsidizing local educational programs and enterprise development projects in local communities, according to Poland’s former Ambassador to the United States and foundation president Jerzy Kozminski.41

In time, some fund-sponsored programs made important contributions. The Polish Fund pioneered mortgage banking, a form of financing previously unavailable in Poland. Aiming to encourage residential construction and home ownership, the Polish-American Mortgage Bank operated by first financing residential construction projects and later furnishing mortgage loans to buyers of the units.42 Mortgage programs are being tried in some countries further east.43

Nowhere was the tension between taking risks and playing it safe, between smaller and larger investments, more pronounced than in Russia, where the business environment generally presented tougher obstacles than in Central Europe. Robert Towbin, who served as president of the Russian-American Enterprise Fund during 18 months in 1994 and 1995, said that, when he set up the office in Russia and hired staff, he envisioned that the fund would invest in small and medium-sized companies.44 But finding such companies was not easy. Racketeers and government-favored monopolies stacked the deck against newcomers and forced many of them out of business. As Towbin put it, “You had to go out to the countryside and find investments.… That’s a lot harder than it looks.” The most successful program, in Towbin’s view, was the small-loans program, a program under which Russian banks found the client and serviced the loan, and the fund put up the money. The bank received half the interest; the fund, the other half. Most of the loans were repaid. Towbin said that “Of all the things the fund has done, the small loans program was probably the most successful.”45

However, the bulk of the fund’s lending ended up consisting of direct equity investment. In this portfolio, Towbin invested in small and medium-sized companies in basic industries such as machinery equipment, dress manufacturing, supermarkets, and finance. Each of these investments was a three- to four-year project. Towbin and other foreigners who worked successfully in the Russian environment underscored the necessity of working with such companies as partners. According to Towbin, “You’ve got to really work with companies who don’t understand the profit motive … to keep expenses down, prices up, and make up the difference in the middle. In contrast to the old days, where the more people you employed, the better you were doing,… you have to take risks and hopefully you’ll get rewards.”46

But other decisionmakers thought that the Russian fund should speculate in vouchers, buy into investment funds, and invest in American companies doing business in Russia. When Towbin resigned over this difference of opinion, many of the commitments he had made were simply dropped and some funding that had been promised never provided. In any case, operating in Russia was far from easy, especially given the amount of corruption in Russian business (including banks), as shown in chapter 4. The Russian fund, generally operating under much more difficult conditions than those in Central Europe, walked a perpetual tightrope between making conservative and risky judgments.

Some business-support programs failed both to make profit and take risks, as the Czech and Slovak Fund demonstrates. A USAID-commissioned evaluation wrote that the fund “is failing to achieve either commercial success or development impact. The investments are suffering major losses, and are generally marginal both in market and in development terms.”47 A member of the fund’s board, which was encouraged to resign following a scandal involving its director,48 emphasized the ambiguity of the funds’ mission. “They are neither fish nor fowl,” he said.49

LOCUS OF LOANS

The tension between the stated mission of the Enterprise Funds and the disbursement of loans also appeared in the geographical concentration of monies. The funds tended to focus on the most developed areas of the recipient countries, where investment already was concentrated, rather than underdeveloped ones. Yet the greater need was often in the latter, where there was little investment.

For example, the Czech Republic experienced “an emerging regional polarisation along the east-west axis,” according to sociologist Michael Illner. Regions with the highest developmental potential were those with higher levels of private business and foreign capital investment and also with many trans-border linkages. The two largest urban centers of Prague and Brno enjoyed especially favorable developmental potential.50

Likewise, in Poland, very low unemployment and a high degree of private-sector development, privatization, and investment characterized a few favored regions. High unemployment, a virtual stalemate in privatization and the development of business infrastructure, and scant foreign investment all were concentrated in certain other regions.51 The Warsaw province accounted for about 41 percent of all foreign capital invested in Poland and about 33 percent of the total number of joint-venture companies in March 1993.52 The pattern of regional disparities (of weak and strong regions) was much the same at the turn of the century.53

This trend holds across the landscape of Central and Eastern Europe: diversity characterizes not only individual countries of the region, but also communities and regions within each country. Summing up a volume of work dealing, in part, with the increasing accentuation of regional, ethnic, and other historical differences after 1989, anthropologists Frances Pine and Sue Bridger state:

The economic prospects of villagers living in beautiful mountain areas near western borders may be very different from those of industrial workers in areas highly polluted by crumbling and archaic factories. For the former, the new order may open opportunities for local developments such as tourism and cross-border trade; for the latter, unemployment and increasing privation has been a more common experience.54

Jacek Szlachta, a specialist in regional development, has a similar assessment: “The leaders of the transformation are the capitals and western portions of countries. The problem areas are the eastern and rural areas. This means efficiency and also means there are areas like Appalachia.”55

Two important experiments designed to narrow this gap were attempted in Poland as the period of Adjustment came into its own: a microlending program under the Enterprise Fund and the EU’s Struder program. These programs had as their goal to provide small loans and/or capital-equity grant support in underdeveloped areas.

The microlending program, a subsidiary of the Polish American Enterprise Fund, funded by the U.S. Congress, got under way in 1995 with a fraction of the operating budget of its parent fund. The program was distinctive in that it served clients with little or no access to bank lending. It provided loans to very small businesses: the average size of its loans was only 7,000 złoty—roughly $2,88756—and the average number of employees in the businesses funded was one to five people. Most firms supported were involved in trading, services (hair dressers, plumbers, construction services, repair shops), and production (bicycles, car parts, toys). As of mid-2000, the program had given more than 34,000 loans, operating through 30 branch centers in Poland.57

The microlending program was designed mostly by Poles familiar with the record of microlending programs elsewhere. The program’s design was an innovative combination of features adapted from other contexts to the Polish environment and grounded in knowledge of Polish cultural practices. For example, prospective recipients of loans first had to find other firms that also needed loans. A system of interdependencies with these firms, building on models tried in Bolivia and Bangladesh, was then established to ensure loan repayment.58 The microlending program has been seen by many as contributing valuable support to Poland’s small businesses.59

The Struder program also made headway toward the goal of supporting small businesses in problem areas. Struder funds sustained some regional institutions and operations, including support for investment projects that created new jobs in the small-business sector. Funds also were provided for the development of small infrastructure projects that were deemed of direct benefit to small and medium-sized enterprises. These programs for regional development were within the framework of Poland’s accession to the EU.60

Fluctuating business conditions in the recipient countries also meant that needs for dollar-denominated loans would change over time and place. The need for Enterprise Funds in the host countries had to be periodically reconsidered due to changing financial conditions. Whereas, for example, in the early 1990s in Poland there was demand for loans under the Enterprise Fund, demand later diminished due to the fact that the fund’s dollar-denominated loans lost attractiveness to borrowers as the Polish inflation rate went down and bank interest rates in złoty declined accordingly. Businesses generally preferred to take credit in local currency. In addition, the Polish banks became increasingly reluctant to refer credit-worthy borrowers to the fund’s program as the banks became more experienced in credit analysis and risk assessment. By 1994, the banks began extending loans to those borrowers themselves.

Thus, to be useful in a given business environment, funds needed to constantly adapt themselves to the vagaries of that environment.61 A USAID-commissioned evaluation concluded that the “Funds must establish an investment philosophy based on a clear understanding of the host country’s business, legal, and policy environments and not simply mirror the approach of other funds.”62 USAID Enterprise Fund adviser Timothy Knowlton put it simply: “Before you start lending money and investing, you should know where you are.”63

LOCAL ADAPTATION, LEADERSHIP, AND THE LIMITS OF WALL STREET

The quality of leadership was a critical factor that determined the demand for, and effectiveness of, the development funds in a given setting. Many fund principals exhibited problems noted earlier with consultants: lack of long-term commitment to their jobs and lack of knowledge about and interest in the realities and business conditions of the countries in which they were operating. As with the consultants discussed in chapter 2, those fund leaders who made extended commitments, grounded themselves in the conditions in which they were working, and developed good working relationships with local people tended to be effective. The tenures of those who did not show respect for the region were often short. Indeed, the funds became noted for a tremendous amount of turnover in leadership.

The relative success of the Slovak Fund versus the Czech Fund—despite the fact that the former operated in a less propitious region— was attributed to its leadership’s commitment and adaptation to local business and cultural practices. Many more deals were finalized in the Slovak Republic than in the Czech Republic according to the GAO.64 The leadership of the Slovak Fund exhibited much more continuity and interest in local business dynamics than did the leadership of the Czech Fund, which was marked by turnover and exhibited little adaptation to the local business climate.65 A USAID-commissioned evaluation concluded that “the Czech fund has not established a viable program.… [It] has been plagued by an inordinate degree of staff turnover, and has failed to put an effective investment team in place.… The Czech Republic has perhaps the most conducive country conditions in all of Eastern Europe, yet the CAEF [Czech American Enterprise Fund] has one of the worst performance records.”66 In 1995, the U.S. government intervened in the fund, closing the Washington and Prague offices, replacing management, and selling the Czech investment portfolio (at a 92 percent loss of its invested capital). Henceforth the fund focused on Slovakia.67

Further east, astute leadership also was often lacking, although even more crucial. Barry Thomas, who previously had worked for the International Executive Service Corporation and Arthur Andersen under USAID contracts in Russia, explained what happened when he served as the chief financial officer for a company in which the U.S.-Russia Investment Fund (which was created in 1995 from the Russian-American Enterprise Fund and another similar fund) invested $5 million in return for a 50 percent ownership interest. This initial “ill-conceived” investment, reported Thomas, “was made without doing conventional planning and future cash flow expectations.… Certain basic things didn’t seem to be part of the investment process: the assessment and development of a business plan, the expectation of future cash flow. Things were pretty loose.” Furthermore, when the company was “disappearing in an insolvent condition with capital having been consumed and no sources of capital, and major problems with one investment, there didn’t seem to be a reaction of the Russian Investment Fund,” despite the company’s preparation of quarterly reports and budgets specifically for the fund.68

The identity crisis of the Enterprise Funds was reflected in, and appears to have been encouraged by, a lack of clarity as to the desired expertise of fund leadership. The funds generally opted to hire investment bankers, but many of those involved in the funds at various levels suggested that people with straightforward business backgrounds were much more needed. Fund overseers and some principals tended to be enamored of a highflying, seemingly sophisticated “investment” approach, involving finance people with major Wall Street reputations. Barry Thomas, who had dealings with the Russian Fund, explained that those hired were “people maybe knowledgeable in Wall Street but not about business—a lot of people from the young MBA marketplace—aspiring investment bankers [whose] business knowledge and background was limited.”69

Yet taking risks in a tough environment such as Russia did not mean that investments and decisions should be made without calculation, business sense, or preparation. The wrong kind of expertise was emphasized: success in such an environment required strong business skills, knowledge of Russian business conditions, and the ability to work closely with local partners to resolve issues. Instead, as Thomas reported, the fund “got enamored with something, put money into something, and didn’t do proper diligence.”70

Financial and marketing skills alone were not sufficient to run a successful Enterprise Fund operation. Paul Gibian, president of the Czech and Slovak Fund further explained:

I don’t think that sophisticated deal structures that investment bankers have created almost as an art form is what is ultimately most important.… The Morgan Stanleys—the numbers people—that may still have a valid role if you talk to airline or utility or energy or [the Czech automobile manufacturer] Skoda because there you have somewhat sophisticated companies that have a market track record.… But the sector that we are trying to support … has less history, so that’s where the operating experience and management evaluation of local companies become much more important.… We need to end up not only with Western financial wizards, but also to develop local operating experience.71

Indeed, the record of the Enterprise Funds demonstrates that financial and marketing skills alone were not sufficient to run a successful operation. A USAID-funded evaluation of the funds concluded:

The most successful funds are those that have built a strong, capable investment staff in the country. Ideally, the staff should be headed by an investment manager from the host country who also has extensive training and experience in business investing.… The presence of a knowledgeable and competent professional investment staff in the host country, combined with an investment strategy that matches the evolving market conditions, is the most important precondition for success.… As new Funds are started, greater effort should be made to understand local market conditions in those countries and to tailor a program that is consistent with market needs and of an appropriate scale.72

A MORE PROMISING APPROACH?

Aid programs to encourage business and infrastructure development suffered from many of the same problems as the other approaches outlined in chapters 2 through 4. Startup was strained and expectations were created that could not be met. Fund representatives were the targets of much of the same kinds of local criticism as were the consultants featured in chapter 2. Like the previous approaches, the effectiveness of the funds in a given case depended largely on the aid workers’ (in this case, the loan officers’) level of adaptation to local conditions, their knowledge of the local players, the quality of their leadership, and their long-term commitment to the effort. The identity crisis of the funds contributed to the problems: tensions between the goals of small, local businesspeople and those of fund managers (including some local elites) who wanted to look good on balance sheets and also to make money fostered frustrated relations between donors and recipients.

However, a major advantage of loan and equity programs to support business was that they did not have to rely on any one group to implement a program. They were more diversified in terms of whom they worked with, and they cooperated with a broader range of recipient individuals and groups. Thus, although the funds achieved uneven results across time and place, as a model they appeared to be more promising than many other aid strategies pursued in Central and Eastern Europe. As USAID Enterprise Fund adviser Knowlton expressed it: “We have spent a gazillion dollars starting stock exchanges as part of privatization. This was premature because value was difficult to determine and there was no transparency and people had nothing to trade. Programs that encourage local private business are the best way we’ve found to achieve our own goal of sustainability.”73