Locked Out

Execution

Jaroenchai Degrom was led down the hallway to the airlocks, followed by Captain Behr and his command retinue. Jaro was dressed in his gray Colloquy Corporation jumper; his hands were bound and he was gagged, per Company Protocols. His deep, onyx-black eyes betrayed no emotion.

I watched from the back of the room with the technicians. I didn’t need to be there, but Jaro was my friend. I struggled to place the emotion the sight of him brought up in me. Benigns, like me, were genetically edited for pragmatism and artisanal work, not emotional intelligence. Sadness? Frustration? Distress? Not that any particular emotion would help. Jaro did what he did in direct violation of Protocols. Everyone knew how that ended.

A guard opened airlock one, and the captain—flanked by two guards and Hila Rask, his counsel (like me, a Benign)—marched Jaro inside. Everyone stepped back, except Jaro and the captain. Hila raised a holographic slate and swiped it to the captain’s wristscreen.

“Turn,” said Captain Behr.

Jaro did, slowly. The captain’s hulking shoulders and long, brown hair dwarfed the small scientist. Jaro appeared indifferent.

“Jaroenchai Navin Degrom,” said the captain, reading from his wristscreen. “You have been found guilty of illegal ship entry and are thereby charged with Corporate Treason, punishable by Article 3.11.A2. Therefore, by the power granted me by God and Colloquy Corporate Protocols, I, Goodman Behr, captain of the Aphelia, sentence you to die by airlock dispersion.

“Do you have any final words?”

One of the guards removed the metal gag around Jaro’s mouth. He looked at the captain for a long moment, then shrugged.

He spared me a glance…and winked.

The captain waved a hand in the air. Guards removed Jaro’s cuffs and shut the airlock door on him. Watching Jaro through the viewing glass, the air around him loudly siphoning out, I thought I might actually cry—an extreme rarity; it was nearly impossible for Benigns to show emotions physically. There was some talk around the ship that an exception might be made for Jaroenchai’s transgression. He was essential to the Aphelia’s mission, after all—a Paradigm scientist heading the exploratory team.

Evidently not that essential.

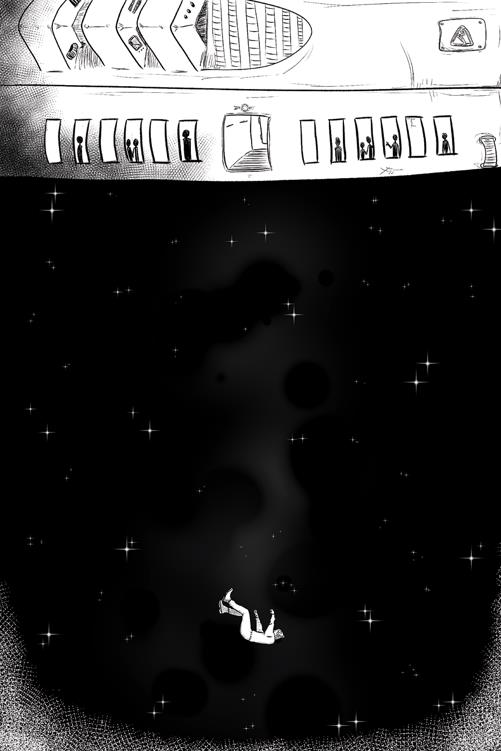

I felt a tightness in my throat, as the airlock warning blared, and my friend was launched into the black vacuum of space.

98 Hours Before Execution

“Hah!” said Jaro, slamming a plastic stein down, sloshing beer on the mess hall table. “They’ve got the gall to work you for twelve hour shifts?”

I shrugged. “My gene editing is largely muscular and cardiovascular. It takes awhile to get tired. I used to work on a ship in the asteroid belt that would keep shifts going for sixteen, eighteen hours.”

“Exploitation,” said Jaro. He scanned the busy room, focusing on the command table. It was weekly social time, so we were allowed alcohol and double rations. We were seated at tables of professional cliques—science, communications, cartography, medical, and technical—each one drunk and loud, as usual.

“Benigns shouldn’t be treated any differently than unedited,” spat Jaro. “Even Paradigms.”

Even though we were far from the command table, I glanced at Captain Behr’s stern figure, worried he might overhear. Jaro’d had a lot of beer. I didn’t stop him, though. Jaro was a Paradigm—a lavishly edited human like the captain and some other Aphelia team leads. Jaro was one of the few Paradigms who was friendly to Benigns, let alone willing to drink with one. When others on the ship saw us socializing, I was told I should feel “honored.”

“I’m used to being worked like a dog,” I said.

Jaro stopped his stein an inch from his face and narrowed his eyes. “Malik,” he said slowly. “Did you just use…a metaphor?”

“No.” I said, with a rehearsed smile. “It was a simile.”

Jaro laughed loudly. He slapped a hand on my shoulder, and I smiled again. “They don’t really respect you, do they?”

“I am paid well.”

“That’s not what I mean.” He leaned in, drunkenly severe. “They don’t…tell you anything?”

“I get my work orders.”

“They don’t tell you what we’re mining.”

My impulse was to respond that they were not mining anything. The Aphelia was an exploratory science vessel. A proper mining vessel would be thrice the size with quintuple the crew, at least. He was referring to the specimens we were collecting from Qallupilluk, the Trans-Neptunian Object (TNO) the Aphelia orbited. Qallupilluk was once a part of Nanook, a much larger, hypothesized TNO, likely a dwarf planet, that had been destroyed at some point in the distant past.

The scientists, like Jaro, had been using drones to harvest small samples of a unique mineral from the TNO’s surface, which they called savirajak. The savirajak had a beautiful blue glow when brought up to the Aphelia by the drones. For precautionary reasons, it was quarantined in the lab until it could be examined in a controlled environment back at Base Tycho.

I don’t correct him, though. Mining was the common, if inaccurate, term—metaphor?—used by the crew.

“What have they told you about savirajak?” he continued.

“It might be dangerous. Perhaps even toxic.”

He burped. “Christ. No one tells Benigns anything.”

I shrugged. “Benigns have been known to unintentionally betray confidence.”

“You don’t resent being left out?”

“No. I respect that you and the scientists will act in our best interests.”

“You’re one-in-a-million, Malik.” He smiled; we clinked steins. “One-in-a-damn-million.”

Execution

I left the airlocks and walked with the others into the ship’s atrium, a cavernous room connecting both levels of the ship, with a fully-grown arbutus tree at its center. Though it was not customary for crew to attend the actual execution, it’s common for them to witness the condemned’s body float out to space. Thus, the majority of the nearly 300 person crew gathered around the viewing glass. I walked to the back of the room and heard muttering: that Jaro had it coming; that he was a good man; that he deserved it; that he didn’t.

Out the window, Jaroenchai Degrom floated silently, pathetically into the blackness. He was still alive; his hands moved. Jaro signed Help repeatedly, likely the only word he remembered from training. Others in the room noted it, too. Many looked away, some cried.

“How long does it take to die out there?” asked an operator, glancing at the time on his wristscreen.

“For a Paradigm?” said a nearby scientist. “Perhaps three minutes.”

Her estimate seemed accurate. Paradigms were edited in every conceivable way—physically, cognitively, psychologically. To edit an effective Benign was expensive; to meet the threshold for a Paradigm was obscene. The fact that the Aphelia had four onboard—three now, I suppose—spoke to the importance of its mission.

“Interesting,” said the operator. “He’s been out there five minutes.”

As Jaro floated outside the viewing screen, about a quarter-kilometer from the Aphelia, he continued to sign.

…Help…

40 Hours Before Execution

I laid on my back in Ion Propulsor Two, cleaning hardened plasma buildup from the inner ring. There’s a misconception that ion thrusters were “clean” energy, which may be true in the ecological sense, but shredding plasmics with a handtorch covered my mask in stinking, noxious film.

My wristscreen beeped and blinked red. Urgent. From Jaro Degrom.

Need a favor, was all it read.

I exited the propulsor. The job was only half-finished, but we’d be in stasis around Qallupilluk for at least another month. Plenty of time to complete the job. Wiping down my mask, I was surprised to see Jaro standing at the console in the center of the engine room—face uncovered.

“You need a mask,” I said, indicating the thick air.

He waved me off. “The dangers of gaseous plasmics have been vastly overstated. Old wives tale! Listen, Malik. I need help.”

As a Benign engineer, I had no business contradicting a Paradigm scientist. Jaro looked fine. Still, I guided him toward a nearby engineering bay, shut the door, and vented the Engine Room.

I removed my mask and washed my face at the sink. “How may I help you?”

“Well, er…” Jaro cleared his throat. He seemed uncharacteristically reserved. Nervous? “I’d like to get back into labs.”

“On-shift is over,” I said, flatly. The day/night cycle was irrelevant on an interstellar craft, but, for organizational and mental health reasons, it was Company Protocol to maintain that superficies. As Chief Engineer, I was one of the few who had access to every area of the ship at all times.

“I know, I know,” said Jaro. “The thing is…there’s something. Something big. Exciting. My research into the savirajak…I need to investigate. Won’t be able to sleep anyway.”

“I thought that the savirajak was being quarantined. That analysis would begin back at Tycho.”

He cocked his head at me, smirking. “Malik…” His face was—questioning? He waited for me to come to my own conclusion.

“You have begun analysis already.”

“And they say Benigns are slow!” Jaro smiled. “I think we’ve established that Behr and his cronies aren’t exactly open books. Please, Malik. It would mean the world. And, hey, if anyone catches me, I’ll blame it on that prick Smithe in maintenance, how about that?”

I hesitated for a moment, but nodded and followed my friend back to the science wing, letting him through the two security doors. He thanked me profusely along the way. Smithe in maintenance was indeed unpleasant, but blaming him would be impossible; my wristscreen would be logged upon entry. If anyone asked, I could say that I was doing routine equipment checks.

I opened lab four—Jaro’s personal lab—and let him in. He thanked me again and pointed.

“Look—”

Floating in a glass observation container in the middle of the lab was a hunk of glowing blue mineral.

Savirajak.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” said Jaro.

I stared for a long moment at its cerulean glow, almost hypnotized. I’d seen it being brought up from Qallupilluk by automated drones many times, but this was different.

“Yes,” I said.

“You’re a good friend, Malik,” Jaro said, smiling as he stepped into the lab. “A very good friend.”

4 Hours After Execution

The Atrium was like a warzone. Faces everywhere—confused, pained, and angry. But mostly, fearful—existential fear.

Four hours had passed, and Jaro Degrom had not died.

He had managed to grab hold of a drone charging cord and pull himself against a steel wing of the ship. He clung to the wing with his legs and continued to sign: Help.

Hypotheses were shared, accusations levied. A practical joke of some kind? Some elaborate ruse? A social experiment, some kind of test, orchestrated by command? One person loudly suggested that perhaps Jaro was wearing some kind of transparent space suit. If such a thing existed, I had never heard of it.

Those not panicked were ecstatic. Crying. Praying. Some called out to God, convinced that we were witnessing something genuinely metaphysical.

Captain Behr stood off to the side with his commanders, his face illustrating no emotion. There had been calls for him to do something—“Bank the ship sharply, commit to the execution!”—“Bring him back inside!”—but he had remained silent, uncharacteristically indecisive.

“This is concerning,” said Hila Rask behind me. “Is there precedent for such an event?”

“If you do not know, I certainly do not.”

She nodded. Her vocation, as Benign counsel, was to memorize Colloquy Corporation’s 600-page Operation Protocols, as well as the Protocols of all major rival companies. Not just a database, but a lawyer capable of interpreting data at a moment’s notice.

“If there’s anything you want to tell me,” she said, “do it now.”

I turned to her. “What do you mean?”

She remained silent for a moment, then said: “There will be a team lead meeting in Command soon. Be there.” And she was gone.

An odd comment. Of course I would be there. As Chief Engineer, I was a team lead. A suggestion of threat?

I stayed in the atrium for several more hours, watching my friend cling for dear life—if that expression still applies—onto the wing of the Aphelia. After some time, he stopped signing and began crawling along the exterior of the ship to the relative safety of the hull. When he was no longer visible, I moved back to work, answering tickets in tech and cartography. I worked like a somnambulist. The rest of the crew, too, returned to work in silence, their eyes wide—concerned, fearful.

At the end of my shift, I returned to the atrium, where many crew members remained gathered. The atrium had taken on a pious atmosphere. People knelt, prayed, stood in silent homage. Votive candles had been lit, Mezuzahs hung. Meditative and protective Buddhas. People held prayer beads, evil eyes, kara bangles. Others, more secular, brought some equipment out into one corner, attempting to scientifically decipher what was happening.

While it wasn’t possible to still see Jaro naturally out of the viewing glass, a drone had moved near him, so crew could easily bring up the holographic feed on their ‘screens. There had been some rudimentary attempts to shoo people away, but Captain Behr had neglected to order the congregation away.

The holoscreen above a workstation they’d wheeled in was by far the clearest I’d seen my friend since he’d been thrown out the airlock. I did a double take at the sight on screen.

Jaro’s face was bright red, and bumpy.

I asked a nearby scientist what was wrong. She shook her head. “We don’t know. Some kind of reaction to being in the vacuum for an extended period of time.”

A nearby medical tech snorted laughter. “I’ve observed dozens of bodies after time in vacuo,” she said. “That is not what they look like.”

“Sure,” said a man—another medical officer. “Tell us all about the very many people who’ve survived prolonged exposure to naked space.”

The woman grumbled at what I presumed was the man’s sarcasm. She pointed at Jaro’s face on the holo. “These divots…They’re unlike any rash I’ve ever seen. Too uniform across the open skin.”

His rough, scarlet face suggested pain. It unsettled me.

The first scientist said, “A reaction between his blood flow and the vacuum. Normally, space is so cold that your blood freezes within less than a minute. Nothing biological has ever survived this long.” She paused. “But that’s only a working hypothesis. In all likelihood, the cause is something we haven’t yet considered.”

19 Hours After Execution

I took my seat around the cartographic map on the Command deck, a large circular table displaying a detailed holographic map of our immediate space. Around the silver representation of the Aphelia hovered about two dozen purple dots, each one representing an automated drone. A large blue orb did not accurately represent Qallupilluk’s true brilliance.

This two-story room had always felt unnecessarily minatory to me. Aside from the glow of the workstations and map table, there were no lights. The table was on a raised platform above a larger command hub. Fifteen feet below us, dozens of shapes milled about in the dark, navigators mostly, maintaining the ship’s orbit. Their chatter was a dull tittering from the shadows.

The Aphelia’s team leads and command retinue sat at intervals around the map. At the head of the table was the captain’s chair, turned away from the map beside an enormous workstation. Behr himself paced the room, while the rest of the team discussed—or, rather, argued.

“Two thrusters, full ionization, heavy bank to the left,” said the head of security, “and none of this ever happened.”

Immediate, forceful protests from the other side of the map. The medical lead said, “You encounter something inexplicable and your first suggestion is to fling it into space?”

He shrugged. “I’m here to suggest solutions, not kowtow to eggheads.”

“That’s disrespectful.”

“Listen. If what you’re bringing on the ship, that blue shit, did something to him—maybe to others—it’s my team that has to deal with—”

“Enough.” Behr’s voice immediately calmed the room. He took his seat, spinning his captain’s chair around to the map. “We need solutions—concrete solutions. Thus far, completing the execution seems to me the most concrete.”

Dissenting voices spoke in discordant unison again. Behr raised his hand. “Bringing him back on the ship is dangerous. The unknowns raise significant concerns.”

“Sir,” said the medical lead, “In science we must confront the unknown, not—”

“Fortunately, I am not a scientist,” interrupted the captain, “and this is not a democracy.”

“Actually, it is.” Hila Rask spoke from the shadows. “This situation may invoke the Clarke Clause.”

No response but some confused murmurs.

“‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’.”

Behr waved his hand. “A popular aphorism.”

She nodded. “Yes, but also a rarely invoked Protocol. ‘When faced with unprecedented circumstances suggesting the fantastic, exceptional solutions should be considered, including, but not limited to, breaking Company Protocol’.”

He stared at Hila. “And your discretion?”

“The Clause should be invoked.”

“Fine. What’s the next step?”

“‘Solutions, however extreme, should be tabled and voted upon by all crew of sound mind’.”

The captain slammed his hand on the edge of the table. Usually a stolid man, the prospect of losing autonomy of his command clearly bothered him.

“Well, perhaps there’s someone here who can elucidate these ‘unprecedented circumstances’.”

He looked up at me, then tapped on his wristscreen. Blue holographic numbers superimposed above the galactic map:

A2234-79.18h.+922°.8°

“Do those numbers mean anything to you, Engineer Malik?”

I stood at attention. Blood rushed to my head—it had been almost thirty hours since I’d slept—but I remained steady. The numbers were galactic coordinates. But outside of this number using the Aphelia as an origin point, I knew little of cartography. “No, sir.”

“Do you have any notion of why I might be asking this?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Tell me.”

“Roughly 60 hours ago, I allowed Jaroenchai Degrom into labs during off-shift. I suspect that whatever he did had something to do with the…infraction for which he was executed.” I nodded to the numbers. “I suspect these do, too. I readily admit to breaking protocol and submit myself to any necessary disciplinary action.”

There was chatter, even chuckling, around the table. Usually thought to be slow-witted, the unedited often illustrate similar surprise at Benign reasoning capabilities.

“Discipline will come in due course,” said Behr. “Degrom sent a cached packet of classified data to these coordinates. A clear sign of corporate espionage. Can you tell us anything else?”

I shook my head. “No, sir.”

“Wait,” said the cartography team lead. “These make no sense.” She reached out her wristscreen and used it to adjust the holographic map like a dial, zooming in. “These coordinates reach out into deep-space.”

“Message to a cloaked ship?” offered another voice.

“Or a message into the void,” said another.

Voices raised. Chatter and speculation began again. All the while, Behr never took his eyes off me.

41 Hours After Execution

I awoke with a start—panting, heaving. A hideous dream, instantly receding. I rose and splashed some water on my face, heart pounding, and was surprised by the time on my wallscreen. I’d barely been asleep an hour. Before finally falling asleep, I’d been awake for more than fifty hours. That I could not sleep like a stone seemed absurd. Were the previous days’ events having more emotional impact than I’d realized?

When I looked up from the sink, I nearly fell backwards.

A face hung there, ringed by the circular viewing port of my quarters—outside the ship. A bright red face with two wide, pitch-dark eyes.

Jaro had somehow crawled around the exterior of the ship. The bumpy rash on his face had…evolved. The bumps were thicker, fatter. Like warts, evenly spread, uniformly indenting his skin.

Because of my editing, I rarely felt fear, disgust, or concern. But the sight of what his face had activated something primal in me—abject, trypophobic revulsion.

I backed away from the viewing port. A hideous dream, surely. I was dreaming, I told myself. Until my friend raised his hand and signed again.

Help.

Then he made a different sign, a movement from his throat down to his stomach.

Hungry.

45 Hours After Execution

I tried to go back to sleep, to convince myself it had been a dream, but I was unable. Sixty hours, no sleep. I decided to rise and return to the atrium.

It was like pandemonium.

A huge, swaying crowd, people screaming at each other. Behr and his retinue stood off to one side, weapons out but not aimed. I watched from beside the arbutus. There had been a few fights. Nearby, a cartographer lay crumpled against the wall with a bloody rag held to his nose. Guards tried to de-escalate and keep peace, but there was too much passion, too much fury in this room. The sheer volume—combined with my sleep deprivation—made my vision quiver.

The sight of the normally rational, hard-working crew in this state was disturbing. Violence could break out at any moment.

I quickly gathered that news about this Clarke Clause—the vote—had gotten around. And everyone had opinions: Jaro should be killed. He should be worshipped. He should be brought to medical. Qallupilluk should be nuked and this entire expedition forgotten. We should repent, ask God’s forgiveness.

“Calm yourselves!” shouted Behr. “We need to be rational and composed, now more than ever.”

“What are you waiting for?” screamed someone in the crowd. “Let’s vote!”

“Miracle!” shouted another, echoed by others and a chorus of: “Let him in! Let him in! Let him in!”

“We will vote,” said Behr, which finally tranquilized the crowd somewhat. He shared a glance with Hila Rask. “But hear this. What’s going on with Jaro Degrom is alien in the truest sense of the word. We have no idea what is causing this, no idea what might happen if we bring him back onto the ship.

“He was executed under the fair decree of Company and God. We should commit to his death, keep the savirajak under quarantine, and return to Tycho. It is the safest, most logical course of action—understood?”

The crowd looked on, silent.

46 Hours After Execution

My magboots locked onto the side of the Aphelia’s exterior with a soundless clunk. I unspooled enough safety cord for twice the length of the ship and attached it to my belt with a carabiner. I looked down towards the engines. Jaro clung to one of the propulsor elevon flaps.

The vote had been handily decided in favor of bringing Jaro back onto the ship. 111 yay—40 nay—139 abstentions. As Chief Engineer with significant spacewalk experience and Jaro’s friend, it was no question who’d get the task of bringing him back in.

I took measured steps towards the ship’s engines at aft. Forty meters. The only sound was my heavy breathing. Thirty meters. I could have moved faster. Perhaps it was the sleep deprivation, perhaps the strangeness of the situation, but I was unusually careful. I wanted to save my friend, yet did not want to see his red, swollen face up close again.

At twenty meters, my wristscreen beeped. Urgent. From Captain Behr. Before I could even answer, his voice came through my comms.

“Listen to me, Malik.” His voice was quiet, severe. “Kill him. Get close, detach him from the ship. Make him float. This is an order.”

“Why?”

“Don’t ask questions. Follow my orders. I will protect you—physically, legally.” I didn’t need to see him to know his teeth were clenched. “I am the captain. You would not be committing treason. I have always acted in the Aphelia’s best interest, now I ask that you do, too.”

I took a moment to collect my thoughts. “You are the captain, sir. But Colloquy Protocol supersedes all, as you know. Therefore, if I were to follow this order, I would, in fact, be committing treason. I’m sorry, sir.”

“Idiot Benign,” he hissed, and my suit comms went dead.

I waited a second before taking another step. My eyes began to fuzz. I blinked repeatedly, trying to clear my vision. Was I right to refuse Behr? My logic was entirely sound, according to Protocol, but I also knew that logically sound actions are not always circumstantially ethical.

Fifteen meters.

No, I told myself—no. Behr simply doesn’t want to relinquish control, to admit defeat. I did not resent Paradigms like some Benigns, despite their more fortuitous editing, but I did see their one glaring, uneditable flaw: a superiority complex. To get a Paradigm to admit they’re wrong is like pulling teeth.

Ten meters.

Jaro clung to the edge of the ion propulsor. He stared at me, waiting. His deep-black eyes beckoned me forward. He reached out a red hand. I shuddered as his knobby flesh came into focus.

My legs shuddered suddenly. Jaro began to shake, too. The exterior of the Aphelia shivered, then quaked.

No—no, no.

The engine was activating.

I started to move faster, but stumbled as a rough ripple moved through the body of the ship. Jaro was only barely clinging to the elevon. Then the ship lurched, and an enormous blast of blue flame burst out the back of the propulsor.

I tripped at the force of the blast and choked on my spit, getting saliva on the inside of the mask. Were we not in the vacuum, the sound would have been deafening. Only the second propulsor fired, but at full force; the ship began to arc in a semi-circle. A huge chunk of hardened plasmics shattered out of the back of the propulsor. I thought, stupidly: I knew I should have finished cleaning that.

I wasn’t thrown off thanks to my magboots. Jaro was not so lucky. Ripped free of his grasp, he was flung into empty space.

Without thinking, I demagnetized my boots and kicked off the ship. I engaged suit thrusters, but Jaro had been thrown off with enormous force. I could hardly see through my suit visor, smeared with saliva and condensation from my breath.

I unclipped a carabiner and reached out my arms; the safety cord unspooled quickly, quickly.

Five feet, four, three, two, and—

Our hands connected, just barely, and I pulled Jaro towards me. I wrapped the cord around his waist and crotch and arms, quickly securing a square knot and reattaching the carabiner to my belt. His entire body was covered in the rashy, red bumps. I realized, nauseated, that the rashy ridges were preventing his hand from slipping out of mine.

Once secure, I felt a sharp tug at the other end of the safety cord. We were being reeled back in. The ship had stopped moving. The engine was dead. Floating there like ragdolls being pulled back to the ship, realization hit: Captain Behr had tried to kill us.

Back in the sealed airlock, I fell to my knees and detached the cord. Jaro crumpled to the floor, followed by a blast of sound and breathable air. The light above the inner airlock door turned green. It opened and crew members poured in to help.

Someone helped me to my feet, another removed my mask. Vacant, hollow words came from all angles:

“Are you alright?”

“Anything broken?”

“Are you bleeding?”

“Is he alright?”

I looked down at the crumpled body of my friend. He’d been turned onto his back, but his chest moved up and down, up and down—breathing. Alive. I knelt beside him.

His face, his skin was indescribable. The wart-like bumps had grown into thick pustules several centimeters each, and rounded at the tips like the limbs of a sea anemone.

Crew members ushered us inside, to medical. Computers, waste bins, people scattered everywhere because of the ship’s movement. I saw two groups in the middle of a fight, screaming at one another. We passed through the atrium.

The crowd remained but now surrounded six or seven figures on their knees in front of the arbutus tree. Captain Behr and his retinue—captive. The head of security’s face was swollen red, beaten. Hila Rask knelt nearby, her nose bloodied.

They had done it, a comms officer told me. He held a guard’s rifle. They had defied the vote and tried to kill us. They had broken into command and sharply banked the ship—throwing us into space.

Behr—on his knees, metal gag in his mouth—stared at me as we exited the atrium into medical.

After Execution

I awoke to blackness after…I do not know how long. I rose to my elbows, sluggish. My sleep had been deep. Memories turned in my head like wet concrete. Everything was a blur; all I knew is that I was examined, bandaged, and put to sleep. My room was completely dark, not even a glow from the ambience of my wallscreen. I examined my arm to discover that my wristscreen, too, was off.

Power failure?

The only light in the room was a thin, pulsating spear of blue across the floor. The door was ajar. When I stood, I nearly collapsed, my legs extraordinarily weak from the sleep. I had no memory of returning to my room last night. Had it only been last night?

Blue emergency lights ran along the length of the walkway. They pulsed in the direction of the consolidation area of the atrium. I followed the pulses, peering into several open rooms and passages as I walked. There was no one.

I began to notice odd, dark marks on the wall and floor. Smears or scratches? Difficult to tell in the low light. Nearing the atrium, the marks became thicker—puddles. An unmistakable, rusty iron scent hung in the air.

If it hadn’t been for the events of the last few days, I would’ve been more shocked at the sight of the atrium. There were bodies everywhere, stacked up against the walls. Mounds of dead flesh. I saw the body of a technician I sometimes sat with during social. Beside the arbutus tree lay the head of Hila Rask. Next to her, the corpse of the security team lead.

The walkway had been cleared of dead. I followed the pulsing lights to the consolidation area, surrounded by floating, firefly-like LEDs. I turned away from them into another, blood-smeared hallway, towards Command.

This room, somehow, still had power. The map table was illuminated. Our neighboring space against a background of stars. I saw the bluish glowing lights of the workstations on the lower level.

Captain Behr’s chair faced away from the map, silhouetted by the glow from his workstation.

“Sir?” I said.

“Malik?” A voice from the chair rasped laughter. “You are awake!”

I approached. “Jaro?”

“That name will do. For now.”

The chair spun around and revealed the man—if it could still be called a man. The red rash of his skin had metastasized. The bumps on his skin had grown into sharp, needle-like points, each one about a half-inch long. The spines glistened and shone as if wet. Points ripped through places on his filthy Aphelia uniform.

And he cradled the severed head of Captain Behr on his lap, his expression locked in mortal terror.

“Thank you for your help.” He held the head out to me in one spiny hand and smiled a smile that reminded me nothing of Jaroenchai Degrom. “You’ve been asleep awhile. Longer than expected.”

“What happened?”

He turned the captain’s head towards himself and gazed into its eyes, as though he were about to recite a monologue. “All of us missed you.” Then he dropped Behr’s head with a wet smack onto the floor.

“What have you done?”

The thing that had been Jaro looked at me, eyes dark. “I cannot thank you enough for your bravery, Malik. Your efforts were invaluable.”

The glow from the lower floor was not from any workstations but the savirajak. Hunks of the blue mineral had been shoved forcibly into the computers and machinery all throughout the Command Deck.

Savirajak powered the ship? How was that possible?

It was then I realized that we were not alone. Black shapes stood in the shadows of the lower floor. Dozens of people lined against the walls. Some held chunks of savirajak.

Watching us.

“Will you come along?” Jaro asked.

I looked from him back to the map, sick. My hands trembled. I found the little silver representation of the Aphelia nestled amongst the digital stars. We were moving. We had a destination—coordinates reaching into deep space. Qallupilluk was nowhere onscreen.

A2234-79.18h.+922°.8°

And below the numbers, the words: Locked In.

How far had we gone? How long had I slept?

“I can’t wait for you to see it, Malik.”

“What?”

My old friend smiled at me. “What we become.”