Author’s Note: The True Story of the Mysterious Stolen Letters

In June 2022, I visited Jersey, on my last research trip to the island, and uncovered a story I shan’t forget.

I had the privilege of visiting a charming elderly man, who shall have to remain anonymous, who told me a story that shows that some secrets simply can’t be lived with.

“I was doing my homework one evening in 1941, eighteen months after the invasion, when in came my two older brothers,” he told me. “They started to open the zips on their jackets and out fell letters, which they had stolen from the German Post Office on Beresford Street. It didn’t surprise me. The pair of them worked as bank clerks and, together with a gang of young teenagers, were always up to tricks, mainly as a way to frustrate and antagonize the Germans.”

That adolescent energy found its release in many outlets, including burning down a German warehouse and flouting curfew. The letter theft was an audacious way to demoralize German troops and could have resulted in deportation or even death.

“They were lucky not to have been caught. They swore me to secrecy and hid them in the bottom of the family piano.”

The teenagers vowed never to speak of the theft again. And there the stolen letters remained, gathering dust year on year, decade after decade. Until 2007, 66 years later, one of the brothers, no longer an impulsive teenager, but a much older and wiser man, decided to hand them back. He walked into Jersey Archive and handed them over after confessing to his brother. “They might be history.”

Jersey Heritage Archive swung into action and took the 86 cards and letters to Jersey Post, who in turn teamed up with Deutsche Post. Handwriting experts, the German military and the German Red Cross were all consulted by Jersey Post and Deutsche Post during their research.

After months of painstaking research on the greetings, dated 16 and 17 December 1941, 10 of the letters were finally handed to their intended recipients.

One from Lance-Corporal Lothar Wilhelm to his fiancée, Kaete Schwartz, read:

Christmas won’t be so happy for me this year, because I’m only happy when I’m with you. God grant that we can spend next year’s Christmas together again. Best wishes and a thousand kisses. Your bridegroom Lothar.

They were delivered to her grandchildren, who surely must have been astonished to hear from their deceased grandmother’s wartime sweetheart.

But alas not all letters could be delivered and many remain at Jersey Archive. I went to view them and found myself lost in a world of forgotten letters. The sentiments and longing expressed by these young German men, a long way from home, reveal the frustration, loneliness and boredom of many fighting a war they did not want to be in.

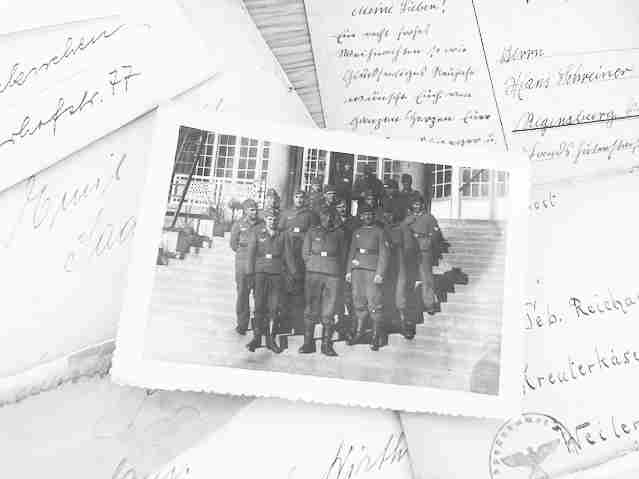

Some of the stolen letters and photos, yellowed with time, kept at Jersey Archive. Images courtesy of Jersey Archive.

One soldier wrote with desperation:

In your last letter you didn’t write “your Maria” any more. I felt offended. I want to spend my life with you. We must be frank with one another. Do I have to be worried? You can be sure of my love.

Did his and Maria’s love stand the test of war? Alas, we shall never know. Some, it seemed, used the German postal service as a kind of long-distance dating club. Writing to Liesel, Josef says:

With this letter I am sending a picture of me that you can see what kind of man I am. On 6 July, it’s my 26th birthday; size 174cm; my nose is in the middle of my face. I like water sports like you. Can you send me a picture of you in your next letter?

And another man wrote, with doomed irony:

Do my letters arrive in time? The war will pass. I’ll be home soon. Your faithful husband.

The war didn’t pass for another three years and you can’t help but wonder if he did make it home.

It felt a bit voyeuristic handling the stolen letters, reading the innermost thoughts and desires of these men as they poured their hearts out onto the page, knowing in some cases, they might never get a reply. But as a piece of social history they are gold dust and, as you can see, inspired Bea’s story.