In no time flat, Uncle Digby had delivered the suitcases to the rooms and everyone had unpacked, ready to start their holiday. Mr Phipps towed Uncle Digby’s car to his workshop. It wasn’t a bother, as they weren’t planning to use the car at all. They wouldn’t need to, because the guesthouse was right in the middle of the village, with the beach just across the road.

Downstairs, the sweet smell of freshly baked cakes filled the air and the long dining room table was perfectly laid with fine china and pretty floral napkins.

‘Mrs Dent, you really didn’t have to go to all this trouble,’ Clarissa protested when she saw the room. ‘We’d have been just as happy in the kitchen.’

‘Oh, my dear, I couldn’t do that to you on your first afternoon. But I might from now on, if you really don’t mind. I’ve got a beautiful old table in there – perhaps we can have breakfast and lunch in the kitchen and I’ll use the dining room in the evenings,’ the old woman suggested.

Clementine thought Mrs Dent had the loveliest smile wrinkles she’d ever seen.

‘Well, I know that Clementine and Uncle Digby and I would be very happy with that, and Aunt Violet will just have to get used to it,’ said Lady Clarissa firmly.

Aunt Violet appeared in the doorway. ‘What will I have to get used to?’ She’d changed out of the navy pants-suit she’d worn for travelling and was now in a smart pair of cream trousers with a red silk blouse and matching ballet flats. Clementine thought that she looked very stylish, although perhaps a bit overdressed for a beach holiday.

‘I was just saying that Mrs Dent didn’t have to go to all this trouble for us. We’d be happy taking tea in the kitchen,’ Clarissa said.

‘Oh yes, absolutely,’ Aunt Violet agreed.

Clarissa was surprised to hear it. So was Clementine, who asked if her great-aunt was feeling all right.

‘Yes, of course. A bit thirsty, but I’m fine,’ the old woman replied. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘Well, at home you’re always grouching that the guests get to use the dining room and we have to stay in the kitchen,’ Clementine explained.

‘Just as long as I don’t have to do any work for the next week, I don’t mind where Mrs Dent feeds us,’ Aunt Violet said.

Clementine stared at her, puzzled. ‘But you don’t do any work at home.’

‘I beg your pardon, young lady,’ the old woman snapped. ‘I’ll have you know I’m a very busy person.’

‘Usually busy complaining,’ said Uncle Digby under his breath.

Aunt Violet spun around and narrowed her eyes. ‘I heard that, Pertwhistle.’

‘Why don’t you all come and have a drink and something to eat?’ said Mrs Dent. She winked at Clementine. She could see that her guests were going to keep her entertained.

Digby Pertwhistle helped seat the ladies, as he was used to doing at home. He glanced up at Mrs Dent, and his forehead creased. ‘I can’t help thinking I’ve met you before, Mrs Dent.’

She looked up. ‘You know, I’ve been thinking the same thing. You look familiar but I don’t recognise your name.’

‘Has the house always taken guests?’ Digby asked.

The woman shook her head. ‘No, my late husband and I bought it as a family home – from my aunt and uncle, actually. They used to come here for holidays. When Hector passed away a few years ago, I turned it into a guesthouse. I couldn’t stand rattling around here on my own.’

Digby frowned. There was a memory scratching inside his head.

‘So much for that mind like a steel trap, eh, Pertwhistle?’ Aunt Violet teased. ‘More like a sieve, don’t you think?’

Digby grinned. ‘Well, as Clementine pointed out earlier, neither of us are spring chickens any more.’

Just as Mrs Dent finished pouring the tea and Lady Clarissa served the cake, the front door banged and there was the sound of feet running down the hallway.

‘I think the children are back,’ said Mrs Dent. She went to intercept them.

‘What have you done with Lavender?’ Uncle Digby asked.

‘She’s having a sleep in her basket,’ Clementine said. ‘She was ’sausted.’

Clementine took a bite of her sponge cake and picked up the glass of lemonade Mrs Dent had poured for her.

‘This is almost as good as Uncle Pierre’s cake,’ said Clemmie, while munching happily.

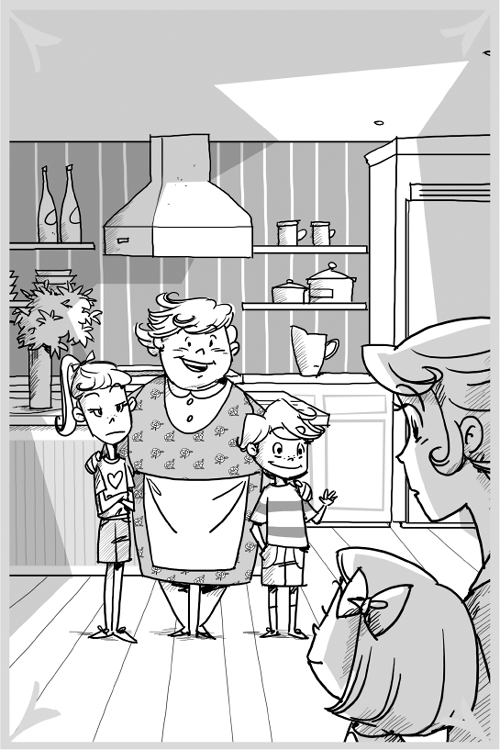

Mrs Dent appeared in the doorway with two children. ‘I’d like you to meet my granddaughter, Della, and my grandson, Freddy.’

The girl was tall and thin with light-brown hair pulled into a ponytail. She had piercing green eyes and wore green shorts and a pink t-shirt with a glittery heart in the centre. The boy was blond-haired and blue-eyed and, on first glance, looked more like Clementine than his sister.

There was a chorus of hellos from the adults.

‘You said she was older,’ Della whispered to her grandmother. ‘She’s just a baby.’

‘Della,’ Mrs Dent chided.

Clementine looked at the girl. She wore nice clothes but her face seemed the complete opposite of her grandmother’s. There was no sparkling and twinkling. Della looked as if she had swallowed something nasty.

‘Freddy, Della, aren’t you going to say hello to Clementine?’ Mrs Dent asked.

‘Hello.’ Freddy gave a shy smile.

‘Hello,’ Della said with a pout.

Clementine’s tummy twinged. Her mother looked at her and nodded.

‘Hello,’ Clementine replied.

Mrs Dent set about cutting some more cake for the children and directed them to sit at the other end of the table, near Clementine.

Soon the adults were chatting about this and that and the children were left to their own devices.

‘How old are you?’ Della asked Clementine with a mouthful of cake.

‘I’m five and a half,’ the younger girl replied.

Della sighed. ‘Granny said that I’d have someone to play with but you’re way too young. I only play with people who are seven and over.’

‘I can do lots of things a seven-year-old can,’ Clementine said hopefully.

‘Like what?’ Della challenged her.

‘I can skip with a rope,’ Clementine said.

‘Any baby can do that,’ Della scoffed.

‘I can read lots of hard words and I can make up poems,’ Clementine said.

‘No, you can’t.’ Della shook her head. ‘Five-year-olds are too stupid to make up poems.’

‘That’s not true,’ Clementine said. She wondered why this girl was so mean and bossy. It seemed strange that her grandmother was about the kindest person Clemmie had met, but Della was crabbier than her teacher, Mrs Bottomley, and Joshua Tribble put together.

‘I can make up a poem about you,’ Clementine blurted.

Della’s eyes narrowed. ‘No, you can’t.’

‘Yes, I can,’ Clementine nodded.

‘Show me then,’ said Della.

Clementine was trying to remember what Uncle Digby had taught her about limericks.

‘There once was a girl called Della . . .’ Clementine stopped. She was thinking about the next line. It was hard to come up with something that rhymed with that name.

Uncle Digby had half an ear on what was happening and leaned over and whispered something to Clementine.

The child smiled.

‘Well, get on with it,’ Della said.

Clementine tried again: ‘There once was a girl called Della, who was in love with a cute little fella –’

Della glared at Clementine. ‘I don’t love anybody!’

‘But I haven’t finished yet.’ Clementine felt her bottom lip wobble. She hadn’t meant to upset the girl.

‘Come on, Freddy. We’re going upstairs.’ Della pushed back her chair and pinched her brother’s arm.

‘Ow,’ the boy complained.

‘Della, why don’t you take Clementine with you too?’ Mrs Dent suggested.

But the girl raced off. Freddy turned and looked at Clementine. He gave an embarrassed half-smile and scurried from the room.

A fat tear sprouted in the corner of Clementine’s eye.

‘Are you all right, darling?’ her mother asked.

Clementine brushed it away and nodded.

Digby Pertwhistle leaned over and kissed the top of the child’s head. ‘Don’t worry about her, Clemmie. I don’t think she appreciates poetry.’

‘Did Della say something to upset you?’ Mrs Dent asked from her seat at the other end of the table.

‘She’d better not have,’ Aunt Violet said tersely.

Clementine shook her head. She didn’t want to get anyone in trouble, especially not if she had to share the house with them for the next week.