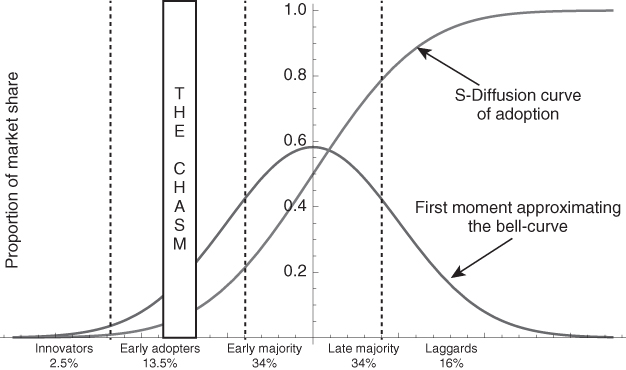

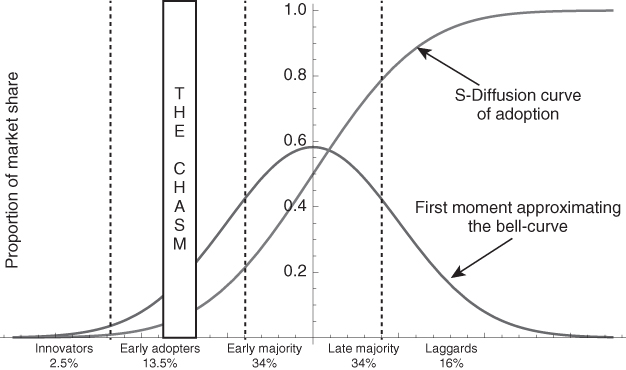

Figure 6.1 Moore's chasm and Rogers' diffusion curve [after Moore, 1991; Rogers et al., 2005].

The most hateful human misfortune is for a wise man to have no influence.

Greek historian Herodotus 484–425 BC.

The people in your social network matter. That is, the makeup of an individual's social network (the kinds of individuals in it) also influences the ideas, attitudes, and beliefs of the individual. In Western society, the value we place on individualism causes us to overlook relational factors in social phenomena. This is an essential principle for understanding social diffusion processes in connected groups. Social diffusion is the process by which ideas, innovations, knowledge, disease, and other things spread through a social group. Although we have all heard of peer influence, most fail to consider its impact when exploring policy decisions or group dynamics. Groups are more stable if they have a variety of roles present, including people in roles designed to encourage socializing, and the presence or absence of particular roles can increase or decrease the likelihood that people engage in threatening behavior such as suicide or civil acts of violence (Palinkas et al., 2004). In this chapter, the social mechanisms for diffusion will be explored and presented in the context of insurgency, industry, health behaviors, and crime.

Many people see insurgency as a natural outcome of unresolved social grievances. For example, if a group of people are enslaved, denied civil rights, oppressed, lack basic needs, or are restricted in religious worship they are thought to engage in insurgent activities as a means of fighting back. Following this logic, if government can address legitimate grievances, the insurgency will lack popular support and fail. Unfortunately, this theory does not account for relational aspects of this social process. As a result, many military counter-insurgency efforts in the past decade have failed. The US military did an excellent job of conducting many civil works projects in Iraq to address social grievances following their occupation in 2003; however, an insurgency developed in the face of these efforts that plagued the US military for 7 years. Successful counter-insurgency efforts by the US military were invariably supported with some degree of influence operations to shape group perceptions of activities. From a more complete understanding of social theory, the importance of these activities can be better understood.

In industry, many believe that the decision by individuals to adopt an innovation is based on the quality of that innovation. For example, if the device is cheaper, faster, better, or solves a problem, then people will want it. Engineering invariably focuses on improving the innovation. Rarely is the social context considered. Cultural anthropologists have studied the diffusion of innovations for years (Rogers, 2003). However, research has shown that the quality of the innovation is usually not the most important factor in the spread of its adoption. In a similar manner, attitudes toward what are acceptable jobs are influenced by those with stronger connections, but information on where to find a job comes from those to whom we are less closely connected (Granovetter, 1978).

Explanations of why people engage in high risk health behavior such as smoking, drug abuse, and unprotected casual sex can also be understood from a social diffusion perspective (Smith and Christakis, 2008). Mercken and colleagues (2010) demonstrated significant affiliation and influence effects on smoking among adolescents. Both of these are relational effects. Valente and colleagues (1997) showed that the underlying social network was important to understanding contraceptive use among women in the Cameroon. Similar studies have demonstrated the importance of social network diffusion in other health applications such as the spread of obesity (Christakis and Fowler, 2007); depression (Rosenquist et al., 2010a); and alcohol consumption (Rosenquist et al., 2010b).

Social diffusion provides an improved understanding of risk factors for criminal behavior. For example, the willingness of young people to engage in crime is highly influenced by their peer group and the lack of male authority figures at home (Glaeser et al., 1996). Traditional approaches that focus on risk at the node level (i.e., age, gender, socioeconomics, drug use, etc.) and neglect relational variables fail to explain why the majority of people characterized by the risk are not affected. In other words, these models have very low explanatory value. Studies of crime in Boston, for example, show that 74% of gun assaults occur in 5% of city block faces and corners (Braga et al., 2010). Furthermore, 75% of gun assaults were committed by less than 1% of the city's youth, who were generally repeat offenders with gang affiliations (Braga et al., 2008).Network models of diffusion have been shown to offer greater explanatory power in the diffusion of crime across social groups (Baerveldt and Snijders, 1994; Houtzager and Baerveldt, 1999).

Closely related to network diffusion theory is Robert Merton's Anomie (also known as Strain) theory (Merton, 1938, 1949). Merton recognized the impact of social structure on behavior and ideology; however, he did not present a formal social network model of his theory. According to strain theory, social groups will often culturally define goals and acceptable means to achieve those goals. In Merton's illustration of his theory within the context of the “American Dream,” he argued that wealth was an American goal and hard work and education were acceptable means to achieve those goals. He further describes the cultural view of people who fail to achieve wealth as lazy, unintelligent, or otherwise defective. Unfortunately, people do not have equal opportunities to achieve goals. Americans born of wealthier parents have greater opportunity to amass wealth than those who are born in poverty. Children of wealthy or highly educated parents have greater access to education. This social inequality across the population places a strain on a segment of individuals. The people will respond with one of five adaptations: conformity, innovation, ritualism, retreat, or rebellion.

The strain adaption is based on their response to the societal goals and means. Individuals who accept both the goals and means will conform, continuing their attempts to achieve social goals through acceptable means. These people follow the rules and societal norms. Actors who accept the goals, yet reject the means are labeled innovators. These individuals seek alternate means to achieve social goals and typically have a blatant disregard for socially accepted means to achieve those goals. These individuals can significantly enhance creative problem solving and develop novel opportunities for an organization. They are also the individuals most likely to engage in criminal activity. When a poor minority with no education is unable to win a high paying job, the innovator is likely to resort to crime in an effort to achieve success through socially unacceptable means. Likewise, the white-collar worker may resort to fraud or other crimes to gain accelerated social mobility. It is the creativity and simultaneous disregard for the rules that makes this individual successful in criminal activities. Actors who follow the rules, yet reject the goal are adapting to strain with ritualism. These people will follow society's rules; however, they have given up hope on attaining the socially established goals. Individuals who have abandoned both the social goal and means make up the remaining two adaptations. People in retreat will disengage from social norms, often replacing goals and means with new counter-cultural norms. These are typically homeless, hermits, or severe alcoholics. Actors in rebellion will replace goals and means and then actively attempt to change the larger social norms. These individuals are most likely to engage in extremist behavior such as terrorism, racial supremacist groups, subversive political parties, and insurgencies.

People who adapt to social inequality through anything but conformity will experience some degree of cognitive dissonance. Extending the theories on balance that were presented in the previous chapter, this cognitive dissonance results from incompatible views between self-identity and the competing social norm (goal attainment or means). This phenomenon leads to the establishment of new social circles with their own subculture. Innovators who engage in criminal activity or deviant behavior to attain social goals, for example, may develop social ties and eventually social circles with other criminals or deviants (Baerveldt and Snijders, 1994). New social norms governing the means of attaining social goals emerge. Those actors that excel under the new social norms will achieve prestige within the newly defined social circle. Similarly, rebellious actors may define both goals and means within the context of a new social circle. Those actors that epitomize the newly established norms achieve greater self-actualization and status. This is an important mechanism for understanding deviant behavior within the context of social structure.

Strain theory has some limitations as a coherent theory. Due to the diversity of social goals and culturally defined means of attaining those goals, there may exist great overlap between the social circles that both define and attract individuals. This overlap makes it difficult to distinguish salient driving variables in group motivation. “One of the major limitations in previous research, however, is that strains are not adequately and properly measured, failing to assess the effects of duration, magnitude, and subjectiveness of strains on delinquency” (Moon et al., 2008). Understanding the strain theory, in combination with the theory of social link formation presented in Chapter 4, however, are important background for our treatment of diffusion in social networks.

Social diffusion is the social context mechanism that governs how people adopt an innovation. In this sense of the word many things can be considered as an innovation. It could be the latest cell phone technology, or it could be a religious ideal, or it could be a moral value/judgment. It could be information or even disease. The term diffusion of innovation takes its name from those who first investigated the topic for marketing of new products. In recent years, these same models have been used to study the spread of just about anything through a social network.

The spread of ideology or innovations in a group of people is extremely dependent on the underlying social structure (Rogers, 2003; Carley, 1995, 2001). It is also dependent on the underlying cultural structure (Carley, 1991). For each person, their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs are a function of both who they know (the social network) and what who they know knows (the knowledge or cultural network). The role of these networks in effecting consensus, belief formation, attitude shifts, knowledge diffusion, collective decision making, cooperation, health, and behavior is well established in the literature (Katz, 1961; Glance and Huberman, 1993; Morris and Kretzschmar, 1995; Rogers, 2003; Carley, 1986, 2001; Friedkin, 2001; Deroïan, 2002; Watts, 2003). From fashion preferences (Aguirre et al., 1988), to willingness to take risks (Pruitt and Teger, 1971), people are influenced by their social network. In general, our ideas, opinions, attitudes, and beliefs are a function of who we interact with, their importance to us, our prior ideas, attitudes, and beliefs, our level of education, new information that we receive, the credibility of that source of information, the emotional content of the message, and the extent to which new information agrees with our existing ideas, attitudes, and beliefs (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Erickson, 1988; Friedkin and Johnsen, 2003).

Our understanding of how the social and cultural structures influence the spread of ideas, attitudes, and beliefs has reached a usable level of maturity. As such, multiple methodologies and models, based on over 60 years of research, exist for tracking, assessing, and using these networks to forecast the spread of ideas, key actors in this spread, and the evolution of beliefs and attitudes.

Some individuals have more influence than others. Within these networks, the attitude and influence of a few individuals can radically alter the collective opinions and actions of the group. That is, some individuals, by virtue of their position in the social network, have disproportional influence (Friedkin and Johnsen, 2003; Coleman et al., 1957). Such individuals are often referred to as opinion leaders or super-empowered individuals or key actors. Lazarsfeld and Katz (1955) suggested a two-step flow model of the impact of media on social behavior in which mass media information is channeled to the “masses” through opinion leaders. In areas where access to mass media is reduced, due to literacy or the cost of accessing the media (lack of Internet penetration, etc.), those with better access to the media and who have a more literate understanding of media content are likely to explain and diffuse the content to others and so have a disproportional influence on changes in ideas, attitudes, and beliefs.

A variation on the opinion leader is the role of the authority figure. In the famous Milgram experiment (Milgram, 1963, 1974) conducted at the Yale University, Milgram studied the willingness of people to obey perceived authority figures, when their instructions conflicted with moral conscience. He found that 26 of the 40 subjects (65%) followed the immoral instructions. This suggests that people can be influenced to a greater degree, by a minority of people, if the minority is seen as an authority figure. In some sense the authority figure is very similar to a node with high prestige within the context of a particular social circle. A key point is that the opinion leader and authority figure may not be obvious. An important step in understanding and assessing organizational risk is to realize that opinion leaders, authority figures, and high prestige nodes exist and have high influence on group behavior.

Chapter 4 presents several theories pertaining to social link formation and the development of social norms and mores. These group values will of course vary from group to group. Individuals who epitomize these group values will hold positions of high status or prestige in the group. These individuals will be able to influence others in the group by virtue of their status. In the context of diffusion, these individuals are known as opinion leaders. Opinion leaders will occupy positions of high centrality in a social network. In general they will have high degree and high closeness centrality and will be able to directly influence many in the group.

An opinion leader must be very careful of what innovations or ideology they adopt. If an opinion leader adopts something that contradicts a group value, they risk losing their status as an opinion leader by no longer epitomizing social norms. Therefore, successful change must be implemented slowly and with the group consensus.

Several factors contribute to successful adoption by group members (Rogers, 2003). First the innovation must have a perceived benefit over the existing status quo. Note that this is not an actual benefit, but there must exist some incentive for some one to change the existing status quo. The innovation must be compatible with existing beliefs and systems. People may refrain from buying the latest new video game if their computer system cannot support the memory and processor requirements. In this instance, the innovation is not compatible with the existing system. There must exist an extreme perceived benefit to motivate the consumer to buy an upgraded system. Likewise, if a radical idea contradicts a moral value held by the group, a compelling case (perceived benefit) must be made to justify the idea. The complexity of the innovation must be low. If the innovation requires too much effort to adopt, it will not be as successful. Trialability is another important consideration. If people can test out a new innovation prior to making a decision to adopt permanently, they will feel more comfortable in their decision.

All of these considerations still speak to the quality of the innovation. The social structure is perhaps an even more significant factor however. Recall that the very source of an opinion leader's influence is in their conformance to group norms and mores. Change agents, by contrast, are individuals who attempt to change the ideology or values of a group or introduce new technology. By definition, they are not similar to the group by nature of their desire to implement change. Successful change occurs when a change agent is able to influence opinion leaders to adopt the innovation, at which point it can spread to the rest of the social group. Reviewing the causes for social links, change agents must make a deliberate effort to establish homophily, reciprocity, proximity, and balance with opinion leaders in order to influence them to change. The change must be measured and incremental, so that their intended changes are not completely unappealing to the opinion leader. Finally, the change agent must consider perceived benefits, compatibility, complexity, and trialability when implementing change.

What are the factors that influence the spread of a new innovation and its adoption?

Spread of a new innovation is influenced by the underlying social and cultural structures. This includes who and what they know, and also what is known by who they know. The adoption of new innovations is affected by its perceived benefit, compatibility with existing beliefs and structures, minimum complexity, and trialability by testing.

In Example 1.2 on page 13, a military noncommissioned officer assumed leadership of a military unit. Although he had formal authority over the unit, his effectiveness was compromised by his failure to recognize a low ranking, yet informal leader within the unit. In his previous assignment, which was very similar to the present one, he had been able to implement many successful changes leading to his promotion and current assignment. In the present unit, none of these measures was effective, due to the animosity between him and the informal leader. This example shows that even military discipline cannot compensate for the strong informal network dynamics. Even formal managers must assess the organizational culture and informal opinion leaders within their organizations. Successful change is implemented in cooperation with the opinion leader.

Chem Coy

Chem Coy is the anonymous name of a large chemical manufacturing company in Western Australia (Alexander et al., 2011). The company attempted to implement a new enterprise resource planning (ERP) tool to improve efficiency and reduce costs. The ERP was a well-validated tool and a proper feasibility study was conducted to determine that the ERP would improve profits if implemented. Consultants were brought in to manage the organizational change as Chem Coy adopted the new system.

The executive level leadership all discussed the new tool and had opportunities to engage in discourse, ask questions, and plan for the ERP implementation. Through these discussions, the executive level leadership reached consensus on the efficacy of the ERP and expressed positive approval of the new tool. Some middle-management and lower-level employees were not consulted on the ERP implementation and were simply told that they would receive training and be required to start using the new system according to a schedule created by the consultants.

The implementation of the new ERP system was considered a failure. One year following the failed implementation, the company was no longer deemed to be competitive, the executive level leadership was laid off, and Chem Coy was merged with its parent company. Subsequent relational algebra (Chapter 7) revealed an informal network in the company's production chain. Central figures in the informal network were not only ignored throughout the implementation of the ERP, they had outspoken objections to the new system that were never addressed. This provides another example where formal authority may not overcome the lack of ideology diffusion throughout the informal network. Perhaps, the ERP implementation would have been effective had management identified informal opinion leaders, sought their buy-in by investing time and resources listening to their concerns and explaining the benefits of the new ERP. These examples demonstrate the importance of social context in diffusion.

True or False. Individuals who attempt to change the ideology or values of a group or introduce new technology are known as opinion leaders.

False. These are known as change agents.

Tightly connected groups are prone to group think. In addition to the impact of the opinion leader there is a social network group effect. That is, research shows repeatedly that groups can exert implicit pressure to influence opinions leading to higher conformity, more extreme views, and a group-think mentality where contradictory evidence is ignored. As discussed in Chapter 4, Asch's study demonstrates how people will ignore first-hand evidence and conform to the common opinion held by the group (Asch, 1955, 1956). Furthermore, Asch found that a single voice among the group that was not unanimous resulted in a drop in conformity from 37% to 5.5%. Asch's finding provided empirical evidence that an individual's perception of reality may be influenced by those with whom they share social connections. This conformity effect increases as people have increased dependence upon the group for social acceptance and when the correct solutions to problems become less clear.

Cliques, isolated tribes, and groups that inhibit interaction with the outside are all more prone to this negative group-think side of networks. This concept is sometimes referred to as social insulation, taking its name from a physics analogy. Thermal insulation works by creating an evacuated space between molecules of high and low temperature, thereby preventing heat transfer. By analogy, a radical idea or innovation is like heat energy that is diffused through a substance through interacting molecules. When there is an evacuated space preventing molecules from interacting, the heat cannot diffuse and the substance will remain hot. With a social network, a radical idea presented to an isolated group has limited resources to verify the veracity of the radical idea. If they see that others may have similar views, Asch's conformity suggests that they are likely to conform to the group's opinion. In contrast, an individual with access to others outside the group with differing opinions has greater freedom in questioning the radical idea. They also have a social freedom to associate with a different social circle that is more compatible with their views. A cult, such as the Branch Davidians in Waco, was able to maintain radical beliefs, because their social network was isolated from the rest of society, and highly connected with those of similar beliefs. Terrorist groups are able to influence insurgents through a social network designed to isolate the insurgent in a group of radical Islamists (Howard and Gunaratna, 2006). In these examples, social insulation is necessary to heat the group views with a radical ideology.

People are more inclined to adopt group beliefs than reality. Individuals need social acceptance as explained in Chapter 4. This inherently requires some level of social conformity. When an actor perceives that group views and his observation are inconsistent, they experience cognitive dissonance resulting from the unbalanced triad. Nyhan and Reifler (2010) demonstrate this concept in politics where they show that citizens will reject certain facts when they contradict political group values. A 2011 poll of US voters showed that three out of four Republican voters thought that the US President could take greater action to reduce gasoline prices, in contrast to one out of four Democrat voters with the same view. In 2006, when there was a Republican president instead of a Democrat, however, the views were reversed. Only one out of four Republican voters thought that the US President could do more to affect gasoline prices, whereas three out of four Democrat voters held the same view. Arguably, the US President has limited ability to affect global gasoline prices and US policies are not significantly different between 2006 and 2011. Why then, would voter views be so different? Nyhan and Reifler's explanation is that when a person holds an affinity for a particular politician and perhaps gains some identity through the represented political party, it is difficult to maintain a view that they are not performing well. This creates a cognitive dissonance. It is easier for the individual to reject the facts in order to support an opinion that provides them identity and acceptance. Thus, the greater extent to which a fact may contradict social norms and values, the more likely an actor will reject the fact in favor of the group belief.

The actual benefit or value of the innovation is not as important as the social structure through which it is diffused. In the 1940s, W. Edward Deming proposed total quality management (TQM), which was largely ignored in the United States. Deming lacked any prestige or opinion leadership at the time. Deming eventually met a leading Japanese businessman, Ichiro Ichikawa, who had a high level of opinion leadership within Japan, whom he convinced of the value of TQM. Through Ichikawa's social network, TQM rapidly diffused and eventually revolutionized quality engineering in Japan, as well as the United States, where it had previously been ignored (Halberstam, 1986).

Another example of failed innovation was evidence that lime juice cured scurvy. James Lancaster, a British sea captain, proposed this innovation in 1601 with little effect. The innovation was rediscovered almost a century and a half later in 1747 by an English Navy physician, James Lind. Neither Lancaster nor Lind held any opinion leadership within their social networks and the innovation was not adopted. It was not until 1795 that scurvy was eradicated throughout the British Navy with the innovation of lime juice (Mosteller, 1981).

Wellin (1955) conducted a 3-year ethnographic study of a failed public health effort to convince families in Los Molinos, Peru, to boil their drinking water to prevent water-borne illnesses that were plaguing the town. A young health professional, Nelida, was sent to educate housewives on the benefits of boiling water. She succeeded in convincing 11 out of approximately 200 families to boil water. Wellin reports that boiling water had a cultural meaning within the target society. Certain objects were considered hot or cold. Water was cold. “Cooking” the water had been culturally linked to illness and members of that society had been taught to detest boiled water. In fact, one woman who adopted the innovation of boiling water became ostracized by other housewives of Los Molinos for her decision to contradict the social norm. In this situation, the reality of water-borne illness was rejected in favor of the cultural belief.

Rogers mapped the diffusion of innovations as the rate of adoption. He observed that the adoption process followed an S-shaped curve, where at a given point in time, the number of adopters rapidly increased and then tapered off after most available people adopted the innovation. He discovered that the rate of adoption over time (the first moment of the adoption curve) approximated the bell curve of the normal probability density function. Rogers categorized the bell curve based on standard deviations from the mean adoption time. The five categories consist of innovators (<2 standard deviations before the mean); early adopters (between 1 and 2 standard deviations before the mean); early majority (between the mean and 1 standard deviation before the mean); late majority (between the mean and 1 standard deviation after the mean); and laggards (later than 1 standard deviation after the mean).

Moore (1991) describes a “chasm” between the early adopters and the early majority to describe the point at which many innovations fail to diffuse. Rogers et al. (2005) further defined a critical threshold, also known as a “tipping point” (Gladwell, 2002) where a sufficient number of adopters are required to generate mass adoption or the death of the innovation. If enough actors adopt the innovation, it may diffuse virally throughout the social network, reaching a saturation point where new adopters are unlikely. Eventually, adoption will fade as new technologies and ideas replace the existing innovation. When introducing an innovation or idea, there are opportunities to affect attitudes toward the innovation up to the tipping point. Past this point, when the innovation is spreading viral, there is little ability to adjust people's perception of the ideology or innovation. There may be opportunity to introduce alternatives that may lower the saturation point or create conditions to induce an earlier drop-off point where the adoption fades. Figure 6.1 shows Rogers' diffusion curve with Moore's chasm.

Figure 6.1 Moore's chasm and Rogers' diffusion curve [after Moore, 1991; Rogers et al., 2005].

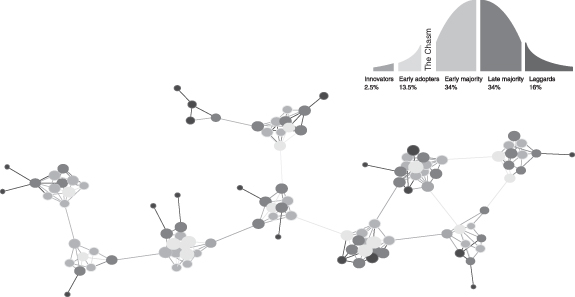

Social network analysis provides tools to map the social structure for which innovations will diffuse. Innovators will occupy boundary spanning, high brokerage positions between network subgroups. Innovators are often not central to a social circle. Centrality is typically correlated with conformity to social norms. Either central figures hold prestige, in part based on their epitomizing social norms or other actors in the network conform to the opinion leader due to their influence. This mechanism creates group think, which actually inhibits innovation. Nodes that span multiple social circles are in a position to diversify their need for acceptance across multiple groups, which frees them to take risk. They are also in a position to broker successful innovations from one social circle to another. In contrast, actors who affiliate with a limited set of social circles are less likely to become aware of potential innovations. Figure 6.2 displays network positions of actors involved in the diffusion process.

Figure 6.2 Actors involved in the diffusion process.

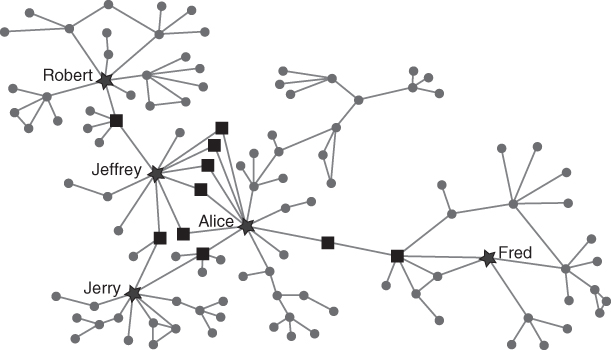

Boundary spanning nodes are not in a position to diffuse an innovation by themselves. The innovator must have a social connection with an opinion leader within a social circle in order to diffuse the idea or innovation. Opinion leaders are often central figures within the network. High degree and closeness centrality are good indicators of opinion leadership. Opinion leaders in Figure 6.3 are represented with a star. Those actors closest to the opinion leader make up the early majority. Innovators are squares. Laggards occupy positions on the edge of a social network with no position of brokerage.

Figure 6.3 Opinion leaders in a network.

An interesting extension of diffusion is a competing influence model. Consider two actors in the network displayed in Figure 6.3: Robert and Fred. Each actor has an opposing ideological belief. For example, Robert believes in government regulation of the economy and Fred believes in free markets. Jeffrey, Alice, and Jerry are in a position to establish the social policy for this notional government. Within this network, Robert is more likely to diffuse his ideology to Jeffrey through the shared connection they have to an innovator. Similarly, Fred is more likely to influence Alice. Jeffrey and Alice share connections with five common alters. Depending upon the position of those five alters on the issue Jeffrey and Alice may be more or less likely to adopt a position. Valente (1996) argues that an actor's likelihood to adopt an innovation is dependent upon the number of alters that have also adopted the innovation. Thus one might argue that if Robert is faster in diffusing his ideology to Jeffrey, who in turn spreads the ideology to the alters he shares with Alice, Alice may be effectively inoculated to Fred's ideas. Fred must now overcome the social norm emerging within Alice's social circle. Assuming that Robert and Fred are effective at convincing Jeffrey and Alice to adopt their respective views, they must in turn diffuse that ideology to Jerry. Jerry shares a single common alter with Jeffrey and similar connection to Alice. In this situation, neither Jeffrey nor Alice is able to gain a consensus advantage for influencing Jerry. Jerry is then socially free to weigh the merits of both ideologies against his current socially accepted values to determine which one he may adopt. Individuals will apply nonnetwork based criteria in making an adoption decision as well. Actors evaluate their perceived value of the innovation, the compatibility with existing ideology or technology, the complexity of the innovation, the perceived risk and commitment. The social network is simply another competing factor in a person's adoption decision. Social pressure is an important and often overlooked factor in social diffusion. The social network may also vet the trust an actor places on the information they receive from others. Alice is more likely to believe the information coming from the shared connection she has with Fred than a non-vetted source. If that information exists outside of Alice's social norms, however, it is not likely that she will adopt the ideology as it would create a cognitive dissonance with group values. Thus, even nonnetwork based criteria can be influenced by social network position.

The discussion thus far has been centered on the dynamics of how influence behaves in networks. This section will identify well-established strategies for group influence, often used in marketing as proposed by Cialdini (2001), or in leadership as proposed by French and Raven (1959). These strategies will be tied back to the network based mechanisms presented earlier in the chapter. Cialdini identifies six principles of influence: reciprocity, commitment, social proof, authority, liking, and scarcity.

Reciprocity, as we have seen in Chapter 4, is a means to establish a relationship. People not only tend to reciprocate friendship, they also reciprocate a favor. This has led to the use of free samples in marketing. In conferences, Cialdini often uses the example of Ethiopia providing humanitarian aid to Mexico after their 1985 earthquake, even though Ethiopia was suffering from a devastating famine and civil war. Ethiopia was reciprocating diplomatic support provided by Mexico after Italy invaded in 1935.

Individuals who commit to an idea, contract, or goal are more likely to honor it, even if the original incentive has been removed. An example is a salesman who either raises the price of a product or discloses hidden fees at the last minute. This technique works, because the individual has already committed to buying the product. The commitment is actually a process where the person has associated the product with their self-identity. They believe that the product may provide greater group acceptance or there may exist a cultural norm to honor commitment. Cialdini ties his definition of commitment to being congruent with self-image. In Chapter 4, self-image was in turn placed in the context of a wider social circle and acceptance. Thus, commitment and self-image may be impacted by network effects.

Social proof is a concept where people do things that others do. Cialdini aligns this back to Asch conformity. This principle is directly related to social acceptance and link formation. People have a tendency to conform to perceived social norms.

Authority has also been presented in this text, earlier in this chapter. Cialdini cites incidents such as the Milgram experiment or the My Lai massacre in the US Vietnam War. People have been demonstrated to conduct even unethical behavior, when directed by a perceived authority figure. The authors posit that the authority figure is actually a group opinion leader. The opinion leader may derive their opinion leadership from a perceived status, expertise, or social prominence within an individual's group. However, it is the individual's desire to gain and maintain membership and acceptance within a social circle that causes them to follow opinion leaders. This modification of Cialdini extends this principle to peer pressure and group think.

People are influenced by people they like. Cialdini shows that people are more likely to buy something if they like the person who is selling it to them. An extension of this is that people who are physically attractive are more likely to be well-liked (Miller, 1970; Dion et al., 1972). People prescribe positive cultural attributes to attractive individuals without realizing it. There are other reasons for individuals to be liked by others, such as their epitomizing cultural norms, which in turn leads to their opinion leadership. Liking is more distinct from opinion leadership in situations where there is an initial or temporary contact with another, such as buying a car. It is unlikely that the customer will ever see the salesperson again after the purchase. However, in this situation, there may still be a desire for social acceptance on the part of the customer, which may make the customer more susceptible to influence by the salesman.

Scarcity is Cialdini's final principle. He explains that offers available for a “limited time only” will make a person more likely to buy. The perception of scarcity will instill a sense of urgency on the part of the buyer, making them more likely to purchase in fear of “missing out.” The authors argue that there must be some other perceived benefit of the product to generate sales. The benefit, if it provides value in a social context, will be a source of acceptance. An individual may normally wait or negotiate to obtain the product at the lowest possible cost, optimizing their benefit. However, if the product is scarce, their desire to have the product outweighs the risk of overpaying for it. Their fear of missing the opportunity outweighs their desire to negotiate for a better price, or taking time to see if others in the social group will adopt the innovation.

French and Raven (1959) identify five bases of power used by leaders to influence others: coercion, reward, legitimate, expert, and referent. Coercion power is the ability of a person to force someone to do something that they do not want to do. This often involves threats or abuse. In a military context, it is the application of combat force upon another population. A leader employing this type of power may threaten to reduce an employee's hours or withhold a bonus. The only means of influence that coercion can achieve is that of short-term compliance. Over time, if coercion is the primary means of influence, if it is applied unfairly across the group, or if it is perceived to be abusive, people will be motivated to resist and undermine that leader. This type of power completely ignores the informal network. It may expect people to conduct actions outside the cultural norm, which may threaten their acceptance and sense of identity. It is not surprising that this type of power is often ineffective in the long run for achieving influence goals.

Reward power is the ability to provide a person something they desire or take away a negative stimulus that they dislike. Rewards are generally more effective than coercion in motivating compliance. Unfortunately, rewards typically need to be greater each time they are applied to have the same influence effect. When rewards no longer have a perceived value, people are no longer influenced by the reward. The perception of value is only understood within the context of the social circle for which it is applied. Thus, if everybody receives a bonus, it becomes a welcome expectation rather than a reward to influence behavior. Opinion leaders are important informal leaders who set value to potential rewards. If the group believes that rewards are being applied in a manner that is unfair or given to people not esteemed by the informal group, reward power can have a negative effect and lead toward group resentment and resistance.

Legitimate power is the ability to instill a sense of obligation or responsibility based on the formal position an individual occupies. This power only lasts as long as individuals occupy the same formal positions. People often expect formal leaders to exercise some degree of coercion and reward in the execution of their duties (Bass, 1990), which creates an interaction effect between legitimate, reward, and coercion power. If the informal group perceives the legitimate power to be abused or applied unfairly, however, it can become an ineffective means of influencing others. Sociologically, the basis for legitimate power is drawn from two complementary theories. The legitimate power is always held by a perceived authority figure and is supported by the Milgram experiments. Secondly, a formal leader's role is legitimized by a culturally accepted view of the social circle that provides the formal leader with his position. Thus, rejecting the formal leader may contradict cultural norms and mores and threaten an individual's acceptance in the social circle. Leaders should recognize that their formal position provides influence only in as much as organizational culture places value on their formal position. Opinion leaders not only have the ability to reinforce the formal leader's position; they have equal ability to undermine the leader and strip him of his legitimate power, even if he retains the formal position.

Expert power is the ability to provide others with access to knowledge, resources, specialized tasks, information, or other forms of expertise. For example, a novice going on a white water rafting trip will listen to (be influenced by) the guide due to his expertise associated with white water rafting. Similarly, an employee may defer to the judgment and guidance of a more experienced colleague. This power, combined with the correct use of reward power develops trust by those who are influenced. The expert power is again based on perceptions held by those in a culturally defined social circle. Some individuals may initially have high expert power based on observed traits such as an advanced degree, military rank, or specialized training. If, however, those individuals fail to demonstrate expertise, make consistent mistakes, or behave in a manner that contradicts the culturally defined norms of their expertise (i.e., a military officer who is physically unfit), they can lose their expert power in the view of those they are trying to influence.

Referent power is the ability to appeal to an individual's sense of personal acceptance or approval. In other words, referent power appeals directly to a person's sense of self-worth. This type of power is derived from position in the informal network. Formal leaders may attain this type of power by engaging in the informal network or demonstrating that they adhere to the culturally defined norms and mores of the group. This power is often manifest as charisma or charm (Raven, 1990). The referent power leader assumes a position as a role model. This type of power is highly effective when combined with other forms of power.

In all cases, however, the ability of an individual to apply any of these bases of power is dependent upon the informal social network and culturally defined norms. These forms of power can be linked to their effectiveness in attitude change. Kelman (1958) identified three types of attitude change: compliance, identification, and internalization. Compliance occurs when a person's behavior is not necessarily linked to their beliefs. An individual complies to avoid punishment, gain reward, or achieve social acceptance. Identification involves a change in belief in an effort to become more similar with someone the person likes or admires. The desire to adopt a new idea is not based on the content of the idea, but on the desire to have a relationship. Identification is an effect of cognitive dissonance in maintaining a positive relationship with an alter who possesses certain beliefs. The beliefs rarely persist beyond the relationship with the alter. Internalization occurs when a belief is intrinsically accepted and merged with the existing values. The content of the belief is considered desirable to the individual and persists beyond relationships with alters.

Coercion power only has the ability to achieve compliance in the short term. Over time, the target population will begin to resist if this is the only base of power applied. Reward power is more effective at achieving compliance than coercion power; however, overtime rewards must be greater and greater. This makes reward power only effective in the short term as well. Legitimate power is necessary to move a person toward identification. However, the legitimate power must be approved of by the cultural norms of the individual's social circle. Leaders who abuse their legitimate power can quickly lose their influence and the target audience will readily move toward compliance as they lose respect for the leader. Expert power is the first base of power that may solicit emulation and begin to broach internalization. However, mistakes or actions that violate expected norms of the expert may cause them to lose the ability to maintain internalized values in a target audience. Thus, expert power only reaches the cusp of the identification–internalization threshold. Referent power is necessary to reach internalization. Referent power appeals directly to a person's core sense of self and as such has greater ability to gain trust and influence an individual's value system. Once an agent internalizes a belief, they are much less likely to change even if the relationship no longer persists. Recall that referent power is gained through direct engagement with the informal social network. It requires behavior consistent with culturally defined norms and relationships with key opinion leaders in the social circle.

Identify the types of power reflected in the following situation:

You are a CEO of a large corporation and your medical practitioner tells you that your blood pressure is too high and if you do not change your lifestyle you will have a heart attack. She advises you to take medication to reduce your hypertension and urges you to replace your current high pressure job with one that is less stressful, enabling you to play more golf, which you really like. You obtain much social acceptance and respect from your position and do not wish to leave this prestigious job.

Networks are ubiquitous. As we have seen, social and cultural networks influence the spread of ideas, beliefs, and attitudes in numerous ways: opinion leaders, hidden sources of authority, group think, composition, and topology. Understanding how social and cultural networks affect the spread of ideas, beliefs, and attitudes is critical to developing an effective strategy to influence a social group. This understanding provides insight into new policy interventions that may prove effective in marketing, managing change, winning asymmetric conflicts, and reducing crime. An ability to understand how ideology spreads through a social network can provide critical insight to industry leaders, military commanders, law enforcement professionals, and organizational planners. This understanding will allow planners to develop improved strategies for influencing social networks through a variety of means.

In applying network principles to counter-insurgency, it is important to balance an understanding of social diffusion with actual and perceived grievances. The first task should be to identify opinion leaders in the social group. The next step is to identify the perceived social grievances according to the opinion leaders. At this point, a change agent, possibly a military leader, can assess what grievances they can address and how they can address these issues. This should involve discussion between the change agent and the opinion leader. As the change agent develops their intervention, they must keep in mind the four factors of successful adoption: perceived benefit, compatibility, complexity, and trialability. It is important to have the opinion leader's buy in to implement any type of social change. Although the change agent needs a reliable product to sell the social group, they must understand that the opinion leader's buy-in is the most critical component to actually implementing and change.

A manager in industry must also recognize the influence of the informal network and his ability to lead depends upon his successful interaction or participation within that network. If we consider a definition of leadership as “convince others to accept your goals as their own,” then a manager's leadership is based not on orders, coercion, and reward, but rather on influence. What source of influence does a manager have? They may have authority or expertise, which may affect their perceived status within the group. There may also be some status ascribed to the rank or status of the position if it is a culturally defined goal of the workplace social circle. If he has some opinion leadership, he may be able to alter the culturally defined goals to make them group performance standards. Involving members of the group in defining goals is an excellent technique to develop consensus; however, a manager with low opinion leadership can easily lose control of this process. Alternatively, the manager can identify the informal opinion leaders through social network analysis; develop relationships with those individuals, understanding the development of social links from Chapter 4; and then convince the opinion leaders to promote the manager's views. Thus, the successful manager must recognize the informal network and then decide to join this network or engage the opinion leaders to influence the group.

An important application area of influence is in marketing. The principles outlined in this chapter demonstrate that the informal social network is more important for marketing an innovation than the actual quality of the innovation itself. Pfeffer (2008) presented an excellent example of marketing a German novel, Das Kind, at the Sunbelt conference. The novel was a thriller, so Pfeffer mapped out a network of bloggers throughout Germany. He modeled several diffusion strategies, concluding that it would be more effective to concentrate resources in one cluster of the network. He designed a mixed-reality online game that served as a prequel to the book. They sent a pizza with a thumb drive taped to the box to 12 central individuals of whom 5 actually put the thumb drive in their computer. The game quickly diffused throughout Germany in the span of a couple months. Two weeks prior to the novel's release it was the twenty-third best seller on Amazon through presales, demonstrating that the calculated diffusion through the network was perhaps more important than the quality of the novel, as no one had read it yet.

Cialdini's six principles of influence for marketing are also dependent upon the informal social network. Crime can be considered an innovation that is diffused. As proposed by strain theory, social inequality exists where there is disparate access to wealth and education. Innovators who reject the acceptable means of attaining wealth and explore crime as an alternative still require social acceptance. These innovators can diffuse crime through opinion leaders or establish new social circles where crime is socially acceptable. Those who excel in criminal activities may gain prestige and become opinion leaders in newly defined cultures where certain crime is acceptable. Strategies to counter crime have focused on removing the strain by providing opportunity to the disadvantaged. This is similar in practice to addressing grievances in counter-insurgency. Strategies must address the social network. Opportunities must be diffused through culturally defined opinion leaders. These opportunities must also be presented in a manner that is culturally acceptable given the norms and mores of the unique social context of the disadvantaged population.

Social networks provide an important context for diffusion and influence. Any effort to influence people must consider the informal network and its unique culture. From insurgency to healthcare, leadership to crime, marketing to politics, the social dynamics of networks are present. This chapter has provided a brief summary of important theories in diffusion and influence and integrated them through a context of social networks.

6.1 List five recent electronic devices that have hit the market. Which of these devices have you adopted? How soon after they were released did you adopt them? Did you buy them because someone you respect had purchased them? Write down where you fit in Rogers' adoption categories (innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, laggards).

6.2 Compare and contrast the roles of the opinion leader, authority figure, and change agent.

6.3 Find examples from your own social networks of the application of Cialdini's six principles of influence.

6.4 You are the manager of two project teams whose performance needs to be raised. You wish them to adopt a new IT system, which will enable them to be more productive as well as result in greater customer satisfaction. Using the models on diffusion and adoption and types of power discussed in this chapter explain how you would achieve your goal.

6.5 Who, in your social networks, is an opinion leader? How much do you trust new information or ideas they give you? How readily do you accept these new ideas when they do not conform to your existing ideas and attitudes?

Aguirre, B. E., Quarantelli, E. L., and Mendoza, J. L. (1988). The collective behavior of fads: the characteristics, effects, and career of streaking. American Sociological Review, 53(4):569–584.

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior, volume 278, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Alexander, P., Armstrong, H., and McCulloh, I. (2011). Towards supply chain excellence using network analysis. IEEE Network Science Workshop.

Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Nature, 176:1009–1011.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. a minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70(9):1–70.

Baerveldt, C. and Snijders, T. (1994). Influences on and from the segmentation of networks: hypotheses and tests. Social Networks, 16(3):213–232.

Bass, B. (1990). Bass & Stogdill's Handbook of Leadership (3rd ed.). Free Press, New York.

Braga, A.A., Hureau, D., and Winship, C. (2008). Losing Faith? Police, Black Churches, and the Resurgence of Youth Violence in Boston. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 6:141–172.

Braga, A., Papachristos, A., and Hureau, D. (2010). The concentration and stability of gun violence at micro places in boston, 1980–2008. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26:33–53. doi: 10.1007/s10940-009-9082-x.

Carley, K. (1991). A theory of group stability. American Sociological Review, 56(3):331–354.

Carley, K. M. (1986). Knowledge acquisition as a social phenomenon. Instructional Science, 14:381–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00051829.

Carley, K. M. (1995). Communication technologies and their effect on cultural homogeneity, consensus, and the diffusion of new ideas. Sociological Perspectives, 38(4):547–571.

Carley, K. M. (2001). Learning and using new ideas; a sociocognitive perspective. In Council, N. R., editor, Diffusion Processes and Fertility Transition: Selected Perspectives, chapter 6, pp. 179–207. National Academy Press, Washington DC.

Christakis, N. and Fowler, J. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(4):370–379.

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. Collins Business Essentials, New York, NY.

Coleman, J., Katz, E., and Menzel, H. (1957). The diffusion of an innovation among physicians. Sociometry, 20(4):253–270.

Deroïan, F. (2002). Formation of social networks and diffusion of innovations. Research Policy, 31(5):835–846.

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., and Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(3):285–290.

Erickson, B. H. (1988). The relational basis of attitudes. In Wellman, B. and Berkowitz, S. D., editors, Social Structures: A Network Approach, volume 2 of Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences, pp. 99–121. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.

French, J. and Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In Cartwright, D. (Ed.), Studies in Social Power. Institute for Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI.

Friedkin, N. E. (2001). Norm formation in social influence networks. Social Networks, 23(3):167–189.

Friedkin, N. E. and Johnsen, E. C. (2003). Attitude Change, Affect Control, and Expectation States in the Formation of Influence Networks. Advances in Group Processes, 20:1–29.

Gladwell, M. (2002). The Tipping Point: How Little Things can make a Big Difference. Little, Brown and Co, Boston, MA.

Glaeser, E. L., Sacerdote, B., and Scheinkman, J. A. (1996). Crime and social interactions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(2):507–548.

Glance, N. S. and Huberman, B. A. (1993). The outbreak of cooperation. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 17(4):281–302.

Granovetter, M. (1978). Threshold models of collective behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 83(6):1420–1443.

Halberstam, D. (1986). The Reckoning. New York, NY: Avon Books.

Houtzager, B. and Baerveldt, C. (1999). Just like normal: a social network study of the relation between petty crime and the intimacy of adolescent friendships. Social Behavior and Personality an International Journal, 27(2):177–192.

Howard, R. and Gunaratna, R. (2006). Winning the war on terrorism in singapore. Lecture given at the United States Military Academy Combating Terrorism Center.

Katz, E. (1961). The social itinerary of technical change: two studies on the diffusion of innovation. Human Organization, 20(2):70–82.

Katz, E. and Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communication. The Free Press, Glencoe, Ill.

Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization: three processes of attitude change. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1):51–60.

Mercken, L., Snijders, T., Steglich, C., Vartiainen, E., and de Vries, H. (2010). Dynamics of adolescent friendship networks and smoking behavior. Social Networks, 32(1):72–81.

Merton, R. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5):672–682.

Merton, R. (1949). Social structure and anomie: Revisions and extensions. In Anshen, R., editor, The Family, pp. 226–257. Harper Brothers, New York.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 67:371–378.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. New York, NY: Harpercollins.

Miller, A. G. (1970). Role of physical attractiveness in impression formation. Psychonomic Science, 19(4):241–243.

Moon, B., Blurton, D., and McCluskey, J. D. (2008). General strain theory and delinquency: focusing on the influences of key strain characteristics on delinquency. Crime & Delinquency, 54(4):582–613.

Moore, G. A. (1991). Crossing the Chasm. Harper Business, New York, NY.

Morris, M. and Kretzschmar, M. (1995). Concurrent partnerships and transmission dynamics in networks. Social Networks, 17:299–318. Social networks and infectious disease: HIV/AIDS.

Mosteller, F. (1981). Innovation and evaluation. Science, 211(4485):881–886.

Nyhan, B. and Reifler, J. (2010). Misinformation and Fact-Checking: Research Findings From Social Science. Washington, DC: New America Foundation.

Palinkas, L. A., Johnson, J. C., Boster, J. S., Rakusa-Suszczewski, S., Klopov, V. P., Fu, X. Q., and Sachdeva, U. (2004). Cross-cultural differences in psychosocial adaption to isolated and confined environments. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 75(11):973–980.

Pfeffer, J. (2008). The structure of buzz: Modeling rumor diffusion in dynamic social networks. Sunbelt XXVIII International Social Network Conference. International Network for Social Network Analysis.

Pruitt, D. G. and Teger, A. I. (1971). Reply to belovitz and finch's comments on “the risky shift in group betting”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7(1):84–86.

Raven, B. H. (1990). Political applications of the psychology of interpersonal influence and social power. Political Psychology, 11(3):493–520.

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations, 5th edition. Free Press, New York, NY.

Rogers, E. M., Medina, U. E., Rivera, M. A., and Wiley, C. J. (2005). Complex adaptive system and the diffusion of innovations. Small, 10(3):30.

Rosenquist, J., Fowler, J., and Christakis, N. (2010a). Social network determinants of depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 16(3):273–281.

Rosenquist, N., Murabito, J., Fowler, J., and Christakis, N. (2010b). The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Annals of Internal Medicine, 152(7):426–433.

Smith, K. P. and Christakis, N. A. (2008). Social networks and health. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1):405–429.

Valente, T. W. (1996). Social network thresholds in the diffusion of innovations. Social Networks, 18(1):69–89.

Valente, T. W., Watkins, S. C., Jato, M. N., Straten, A. V. D., and Tsitsol, L.-P. M. (1997). Social network associations with contraceptive use among cameroonian women in voluntary associations. Social Science Medicine, 45(5):677–687.

Watts, D. (2003). Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, New York, NY.

Wellin, E. (1955). Water boiling in a peruvian town. In Paul, B. D., editor, Health, Culture, and Community: Case Studies of Public Reactions to Health Programs, pp. 71–103. Russell Sage, New York, NY.