WHEN THORNTON WILDER GRADUATED FROM YALE IN JUNE 1920, he was the only one of the five Wilder children who had never been to Europe. His youngest sisters, Isabel and Janet, lived in Italy and Switzerland with their mother from 1911 to 1913 while Thornton and his sister Charlotte were in school in China and then California. After her college graduation in 1919, Charlotte worked in a YWCA hostel in Milan, Italy. In June 1920, Thornton’s brother, Amos, who had served overseas during World War I, returned to Europe after receiving his Yale degree and began a fellowship at the University of Brussels. Thornton’s immediate future was decided when he was accepted as a paying visiting student and boarder in the School of Classical Studies at the American Academy in Rome for the term beginning in October 1920.

Worried about his second son’s employment after college, Wilder’s father encouraged him to enter the teaching profession as a prep school Latin instructor. The elder Wilder believed that his son’s enrollment in the School of Classical Studies would enhance his credentials on job applications. Despite the family’s limited resources, the foreign exchange rate was so favorable that nine hundred dollars—which the senior Wilder doled out in installments—fully covered his son’s year abroad. Before Wilder sailed for Italy on September 1, he completed six weeks of work in the last of five farm jobs he had held over the past seven summers.

Wilder arrived in Rome on October 14, 1920, and remained at the American Academy for seven months, taking graduate courses and participating in student social life. His social circle widened due to informal introductions to young American embassy personnel and more formal introductions from family and friends that provided him entrée to the large English and American community in Rome. He especially enjoyed his visits to the home of the Italian poet Adolfo de Bosis and his family, where on one occasion he met Ezra Pound. Wilder continued his writing, focusing on playwriting. He hoped to complete “Villa Rhabini,” a play with strong Jamesian overtones, and to read it to some of the literary ladies whose tea parties he frequented. He made short trips to other parts of Italy, such as his “Umbrian week” in Perugia and Assisi. After leaving the American Academy in Rome on May 18, 1921, he explored Florence and nearby Siena and stopped off in Milan to see his sister Charlotte.

From the time Wilder learned he was to go to Rome, he longed to spend time in Paris. He wanted to see a close friend who was studying music there, and to attend performances at the Vieux-Columbier, a theater established in 1913, whose founder, Jacques Copeau, employed novel stage techniques Wilder had read about and wished to experience firsthand. In early June, Wilder arrived in Paris, where he spent two and a half months. Although he had initially planned to stay there a shorter time, his father cabled him to say that the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey had offered Thornton a position as a French teacher. Once Wilder accepted the offer, he felt it necessary to study and immerse himself in French grammar and conversation.

While Wilder was in Paris, his mother and two youngest sisters sailed for Southampton, England. They spent time in London with Wilder’s maternal aunt, Charlotte Tappan Niven, and visited Amos, who had completed his fellowship year and was living and working at Toynbee Hall, the oldest settlement house in London. When Amos matriculated that fall at Mansfield College, Oxford, to study for a degree in theology, Mrs. Wilder and her daughters took up residence in that academic community. While the foursome settled down in Oxford, both Thornton and Charlotte left the Continent at the end of the summer. Charlotte gave up her job in Milan to work in Boston, and Thornton left Paris on August 31, 1921, on board the French liner Roussillon, to begin his teaching job at Lawrenceville, a private boarding school for boys. Their father had remained in New Haven, where he was now associate editor of the New Haven Journal-Courier. Once again, the Wilder family was separated by an ocean.

From September 1921 to June 1925, Wilder taught French and served as the assistant housemaster of Davis House, a dormitory at Lawrenceville. The school and the surrounding community provided a congenial place for Wilder to earn his living and continue his writing projects. He became especially close to Edwin Clyde Foresman, the housemaster at Davis, his wife, Grace, and their young daughter Emily, and to C. Leslie Glenn, a young math teacher who later became a distinguished Episcopal clergyman. Glenn remained a close friend for the rest of Wilder’s life. Nearby Princeton University had a wonderful library and kindred groups of musicians and literary figures. Lawrenceville was also only a short train ride from Trenton, Philadelphia, and New York City, where the off-duty schoolmaster could easily enjoy the current theatrical fare. As a result, during this time, Wilder broadened his ties to literary and dramatic circles in New York. These associations fostered his writing life, provided informal but professional criticism of his work, introduced him to Off-Broadway theatrical groups, and opened doors to residential programs for aspiring writers.

In the fall of 1925, Wilder, the successful teacher and housemaster, took a two-year leave of absence from Lawrenceville to enter the graduate program in French at Princeton University. The three siblings closest to him in age had either completed degrees or were about to enter graduate programs. Charlotte, who had received her M.A. in English from Radcliffe in June 1925, began teaching at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts. Amos returned from England in 1923 (as did Mrs. Wilder and her two youngest daughters) and completed his B.D. degree at the Yale nity School in 1924. After a year of tutoring and travel in the Middle East, Amos was ordained in 1925 and became the minister of the First Congregational Church in North Conway, New Hampshire. When Isabel returned from England in 1923, she worked for two years in New York before entering the three year certificate program at the Yale School of Drama. The youngest sister, Janet, now fifteen, attended high school and lived with her parents, who had moved from Mount Carmel, Connecticut, to Mansfield Street in New Haven. In the fall of 1925, the members of the Wilder family were not only all together on the same continent but living near one another in the Northeast.

Thornton Wilder’s commitment to graduate studies did not affect his determination to pursue a writing life, nor did it stifle the ideas, characters, and plots that filled his imagination. During July 1924, when he was awarded his first residency at the MacDowell Colony, an artist’s retreat in Peterborough, New Hampshire, he concentrated on a group of “Roman Portraits” he had begun in 1921, probably in Paris. He had worked on these pieces intermittently, but there was a new impetus to complete them. In March 1925, he had received welcome news from a Yale classmate who was working at a publishing house. He had requested a copy of Wilder’s manuscript months before and had shown it to the directors of his firm. Now they were interested in publishing it. Wilder expanded and revised the manuscript, and in November 1925, a month after he began his graduate studies, he signed a contract for his first novel. The Cabala was published in the United States by Albert & Charles Boni in April 1926 and in England by Longmans, Green in October of that year. Most reviews were positive and sales were strong, although not sufficient for Wilder to live by his pen alone.

After Wilder received his M.A. degree from Princeton in June 1926, he returned to the summer routine he had followed since his second year of teaching, dividing his vacation into two parts. He reserved one month to write and another to earn money tutoring at a boys’ camp. In July 1926, he was accepted for a second residency at MacDowell, where he began a new book. In August, he returned to Sunapee, the tutoring camp where he had been employed for the past two summers. From late September until the beginning of December, Wilder toured Europe as the paid companion of a boy he had tutored the previous spring. By December, he was in Paris, where he remained when his duties as companion had ended. There he met another young American author, Ernest Hemingway, whose second novel, The Sun Also Rises, had been published that year to excellent reviews, and whose writing Wilder admired.

Wilder enjoyed a banner year in 1926: In addition to the publication in April of his first book, on December 10, 1926, The Trumpet Shall Sound, a slightly revised version of a play that had won a Yale writing prize in 1920, was directed by Richard Boleslavsky at the Off-Broadway American Laboratory Theatre. Although it did not receive favorable reviews, the play remained in repertory for several months. Wilder was not overly concerned about its reception, because he was then deeply engaged in a new work, a novel set in Peru. He worked on it over the Christmas holidays, which he spent at a pension on the French Riviera with some Yale friends who were now studying at Oxford. There he met Glenway Wescott, another contemporary author he admired.

On January 31, 1927, Wilder sailed for New York on the Asconia. He rented rooms in New Haven, where, away from the hubbub of family life, he would have a quiet place to work on his second novel. Shortly thereafter, to supplement his small income, he accepted a six-week residential tutoring job in Briarcliff, New York, from February to early April, and also agreed that spring to translate a French novel for his English publisher. In July, at the urging of his father and the headmaster of Lawrenceville, he accepted the position of housemaster of his old dormitory, following the untimely death of Edwin Clyde Fores-man. Throughout this period, Wilder worked on his Peruvian novel. In July 1927, a year after he began it at the MacDowell Colony, Wilder delivered the final manuscript of The Bridge of San Luis Rey to his publisher. In August, he resumed his tutoring position at the camp in New Hampshire.

The academic year 1927-1928 at Lawrenceville began inauspiciously. The new housemaster, with his three-thousand-dollar-a-year salary, settled into his six-room quarters and prepared for the customary trials and tribulations that punctuated residential life at a boys’ school. The first trial, however, had nothing to do with his charges. A few weeks into the fall term, Wilder had a mild attack of appendicitis but was able to return to his duties. Another flare-up later in the fall required surgery and an absence from teaching.

The Bridge of San Luis Rey was published in the United States on November 3, 1927 (the English edition had appeared the previous month), to rave reviews and stunning sales on both sides of the Atlantic. By the time Wilder traveled to Miami, Florida, over the Christmas holidays to recuperate from his surgery, it had become clear that his second novel was already a huge success. The implications of this became apparent when he returned to Lawrenceville for the spring term: His dormitory home was deluged with telegrams and letters requesting interviews and speaking engagements, and packages of books to be signed were delivered daily. Most gratifying, perhaps, were invitations to meet notable authors whom Wilder, hitherto, had admired only from afar. In May, his novel won the Pulitzer Prize. Wilder had suddenly become an acclaimed author with a popular following and a great deal of money in his pocket.

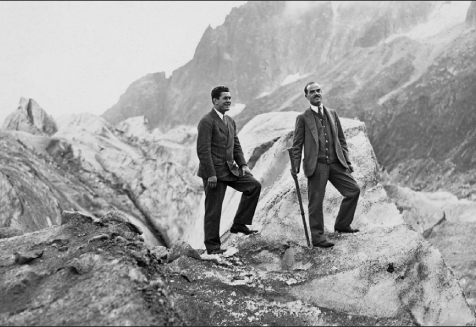

In June 1928, Wilder resigned his position at Lawrenceville, but his association with the school was not entirely severed. At the beginning of July, he sailed for Europe with three Lawrenceville boys he had agreed to chaperone for a few weeks in England. After some travel, they joined Wilder’s mother and two younger sisters in a large house in Surrey he had rented for his family. Wilder stayed on in Europe for the rest of the year. During his recuperation in Miami the previous December he had made a new friend, someone just his age, and had planned a walking trip in the Alps with him for September. His companion was the book-loving heavyweight boxing champion of the world, Gene Tunney, an acclaimed athlete and international celebrity. Because Wilder’s recent success had turned him into a literary lion, it was not surprising that this seemingly disparate pair attracted widespread press attention, which continually interrupted their trip. The press surveillance ended only when the two men were able to slip down to Rome for Tunney’s private wedding.

With that furor behind him, Wilder retreated to the south of France, where he spent a month writing, exercising, and socializing before meeting his sister Isabel for a round of theatergoing, concerts, and visits to museums in Munich and Vienna. After spending Christmas with their aunt Charlotte in Switzerland, Wilder and Isabel returned home at the end of January 1929. No longer could he pursue his vocation as a writer in relative anonymity. From this point until the end of his life, forty-six years later, Thornton Wilder was to live the life of an internationally renowned and acclaimed literary figure. In this climate, the privacy and seclusion he needed to pursue his vocation became increasingly difficult to find.

Oct. 14 <1920>

Roma

Dear Family:

I have this minute arrived in Rome, and am waiting up in my room at half-past ten for some supper. The train was two-and-a-half hours late, and I know no more of Rome than can be gained on rainy evenings crossing the street that separates the station from the Hotel Continentale (the last room left for 22 lire). I had resolved not to write you until I had received your letters forwarded, but they failed day by day to come so I have hurried up to Rome to get them. French Lemon1 may have decided not to forward to Cocumella on the Wagers’ casual advice, or they may be found at the Boston. Tomorrow will straighten out.

In the meantime (while my hunger resounds in my stomach like a great bell) I must tell you some of the news of the last week and a half in Sorrento. One day for instance when I had been walking enraptured for hours among the bronzes and marbles of the Museo Nazionale I returned at 3:30 to the Immaculata to take the Sorrento boat. I bought my ticket, went aboard; it was expected<inspected> by three guards. We started and I settled down to read my Paris Temps and Berliner Tageblatt.2 I fell into conversation with an Italian sailor who had had a fruit store on upper Broadway. Suddenly I found I was on the wrong boat: I was bound for Procida and Ischia, and there was no return that night. Seaman Esposito embarrassedly offered to take me into his home at Procida but I laughed it off, saying that I would go on to the Ischia that had been good enough for Vittoria Collonna and Lamartine.3 Then I fell into conversation with a handsome middle-aged Anglo Italian who is employed between London and Rome in the wheat business. There are half a dozen exceedingly beautiful villas on Ischia because the bathing is so perfect for children, there being no cliffs as at Sorrento. This gentleman tried to be as helpful to me as possible, but with a touch of caution. I was hatless, in an eccentric-looking baggy grey-suit, and with a strange air of being at my ease that suggested arriére-pensée.4 We drove up towards his villa, whereupon he extricated himself, telling the coachman to carry me on to the Floridiana Hotel (“the best one” on the Island, but not very good.) In the glass of my Italian, darkly, I found the Floridiana closed for the season, and was waved on to the second best which was full. Then I was sent to the Albergo del’ belli guiardini<giardini> which turned out to be a rather ambitious kitchen-in-the-wall, peopled by several suspicious old women in black dresses who discussed things in whispers among themselves. I feared I was going to sleep in Vittoria Collonna’s castle, now a house of correction, but one of the women emerged and beckoned to me ungraciously to follow her. We passed to an outdoor court (the beautiful gardens perhaps of the title) and on the second story through four spacious dark funereal bedrooms, there being no hall, and no light, and no privacy. The last was offered to me, to my simulated delight, and I gazed at the great shapeless shabby bed where so soon (I foresaw) my throat would be cut. I wanted to keep my relations with my hosts as sweet as possible and so refrained from bargaining until the morning. I slept very well; I was awakened only once by a dog under my bed eating the Paris Temps, the Berliner Tageblatt having been used in a more humble and not inappropriate way elsewhere. The return boat for Naples left at six the next morning and I had told them to call me at five, so I lazily replied to a knocking in the dark. It seemed to me, as always on waking, that I was happily back at 72 Conn. or on Whitney Avenue.5 Soon the truth came to me that I was in a dubious situation on the island of Ischia. I threw some cold water at my face from a washstand in the corner, dressed and descended. There was a yellow streak in a dark sky visible above the narrow blanching street. By lamplight my padrona made me a cup of coffee and presented her conto.6 Twenty-two lire for that wretched room, a supper and a breakfast! It was too late to argue. I paid it and threw myself on circumstance. Except for my Express checks which were uncashable until late in the morning I had only three lire left, and the fare to Naples was five lire. I asked the woman if she’d give me two more, and I’d mail her five, but she concealed her obduracy under a flow of rapid Neapolitan dialetta.7 I left quickly without mancia8 and reaching the ticket-kiosk explained myself to the official. Suddenly it occurred to me that 3 lire would at least buy me a 3rdClass passage, and so it did with a lire to spare. So at ten o’clock I reached Naples and going to beloved piazza dei Martiri cashed another Express at 25 lire to the dollar! Suddenly I passed an American soldier (as I thought) in the street. I ran back and spoke to him, inviting him to have an ice-cream with me. He turned out to be a Princeton boy of <an> imposing New York family who ran away from bank servitude to join the Near Eastern Relief. He was actually in the Wall Street Explosion.9 The J. P. Morgan skylight fell on him, and he’s got the scars! He came over and spent two days with me at the Cocumella, and we went to Pompeii and climbed Vesuvius together. (I keep going to the window. Outside in wonderful Rome, it is drizzling. Carriages and trams pass. Not far away the Pope and forty cardinals are sleeping, the coliseum and the forum are lying dampish, and silent and locked up but with one burning light at least, the Sistine chapel is glimmering, and somewhere further off, in the struggling starlight, your graves, John Keats and Percy Shelley, lie, succeeding to establish, if anyone can, that it is better to be in a moist hell with glory, than live in an elegant hotel with stupidity.) When we got quarter way up Vesuvius, at a hotel where are<our> horses were supposed to be waiting saddled for us, there were suddenly no horses. So we cut the price of our agents in half and agreed to walk. It’s a wicked mountain, half of every step you take is lost in the sliding blue-black dust, yet so steep that every step for two hours and a half is palpably lift. I suddenly got anxious about Charley White; he has been shut up in a bank for a year and a half and was unprepared for this. He insisted on going on, though he was on the verge of palpit<at>ions and heaves and blood-coughing the whole way. Yet Father and I had wisely let pass the call of the Near Eastern Relief because of my constitution: I who talked Italian all the way up with our guide, Nicola!

(Now it is morning and Stupidity is impatiently waiting for café-au-lait. A busy modern city with only a hint of romance is riding the tide under my window. In a few moments I am going to dash over to French-Lemons; then to the Londres-Cargill, an almost unheard of hotel with a room at about eight lire! Then this afternoon to the Academia.)

Love to you all. I’m dying to know about you.

Will write again tonight

Thornton

Looking in the cheval-glass I see a young man of about twenty-one who implicitly, or by his reason of his large shell glasses, presents an expectant eager face to the view. His shoes and clothes are in travelstate, but he is carefully shaved and brushed. On his pink cheeks and almost infantile mouth lies a young innocence that is not native to Italy and has to be imported in hollow ships, and about the eyes there is the same strong naivete, mercifully mitigated by a sort of frightened humor. He is very likely more intelligent than he looks, and less charming. Alone in Italy? To study archaeology! Why each single tooth in that engaging upper row is an appeal in the name of Froebel and in the name of Wordsworth to let childhood enjoy its rainbow skies and imagined gardens while it may.10 A delicious little breakfast has come, with a marmalade of orange and pineapple, and though I want you all here all the time, for this particular meal I choose Isabel.

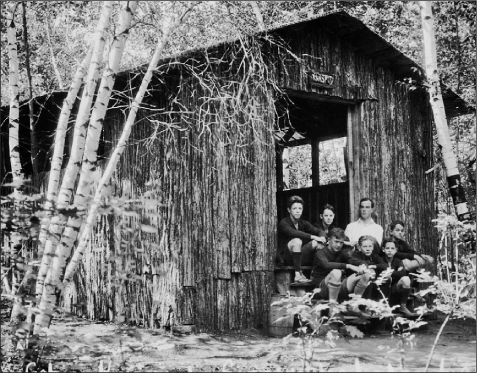

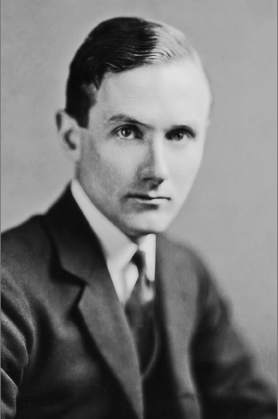

TNW’s Yale graduation photograph, 1920.

TNW’s Yale graduation photograph, 1920. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Am. Acad. At Rome

Dec. 4, 1920

Dear Papa:

I have received the remittance and acknowledge statim.11 I was told it was coming the latter half of November and had planned things down to a science. Its delay by so much as a week (to say the least) compelled me to ask the Secretary here to forward one hundred and fifty lire, as you will see on the bill enclosed. I was also told that you were sending me eighty dollars, which on the day of your mailing would have been at l<e>ast Lire 2160 and more likely £2300. I presume of course that you got full exchange (otherwise you would have left the exchanging to me as the advantage lies here) and that your remittance was $55. about.

If this means that your method of conducting my arrangement has changed it deserved explanation before it was put in practice. I gratefully accept anything, but like to know the worst. If I am to <be> paid with you getting the benefit of the exchange, I shan’t be able to go with the Classical School for three weeks to Pompeii; I shan’t be able even to buy the pocket microscope we must have for the numismatics study in the course on Roman Private Life. I shan’t be able to go to the Opera, which definitely narrows my visit to Europe as being purely Classical Study.

Out of the 1500 I have already paid:

| The bill for November | Lire 709.45 |

| 10 Italian lessons | 70.00 |

| A pair of gloves | 45.00 |

I’ve immediately stopped Italian lessons.

Is the idea for me to stay in Italy as long as I can for $900, or is it to stay for one year under as pinched conditions as possible? We parted on the first agreement.

On a generous amount of money I could make quite a little agitation on this Roman scene that recognizes extraordinary eccentric sharp young men, as it did when Emperors adopted them! Enclose yesterday’s cards received.

On a generous amount of money I could make quite a little agitation on this Roman scene that recognizes extraordinary eccentric sharp young men, as it did when Emperors adopted them! Enclose yesterday’s cards received.

On a discreet amount I could still do the name Wilder modest credit and gain entrance to regions incomputably valuable to a younger writer who misses nothing, as far as observation goes.

On a discreet amount I could still do the name Wilder modest credit and gain entrance to regions incomputably valuable to a younger writer who misses nothing, as far as observation goes.

On an adequate student allowance I can walk about and see things and meet rather complacent Americans at the hotels, and do a little work without worries, and with an extraordinary amount of pleasure.

On an adequate student allowance I can walk about and see things and meet rather complacent Americans at the hotels, and do a little work without worries, and with an extraordinary amount of pleasure.

At present, as a shabby repressed soul, I can breathe and go into museums (not too often) and get a great deal of pleasure in a denied, envious sort of way with all my capabilities still in the cocoon.

At present, as a shabby repressed soul, I can breathe and go into museums (not too often) and get a great deal of pleasure in a denied, envious sort of way with all my capabilities still in the cocoon.

love

Thornton

<appeared perpendicularly in left margin>

On my margin I couldn’t b<u>y any Xmas presents on time. Photos later,—

Porta San Pancrazio

Roma Italia

Dec 13, 1920

Dear Amos:

I’m so ashamed at not writing before, especially in view of your closely-written and -observed letters, that I don’t know what to say. I have certainly be<en> idler than you, too, full though my days have been with sightseeing and lectures. I think I must unconsciously have postponed writing you from pique at your intimation that I was probably on the point of borrowing money from you, a terror which Charlotte also experiences, and gratuitously reminds me from time to time that she hasn’t enough to live on herself. Hug your avarice as closely as you please; it never occurred to me to borrow from either of you! Though, since both of you got the idea simultaneously I suppose penury and dependance are as conspicuous as two red flags in my temperament, or else father, whose idée fixe about borrowing is perfectly Freudian, has been warning you about what he calls the Leech of Rome. I have every intention of being parasitic all my life, but always on those who can easily afford so expensive an encumbrance and who take a special delight in subsidizing those talents to which I make so modest a claim. I have at last found in Italy a mecca for just such patrons, and am myself presenting myself as a sort of objet-d’art of a most singular and quaint charm, rentable for teas, dinner-parties and dances; will read MSS plays to adoring ladies; will sit in their palaces and talk to them about their own uniqueness; will — and so on, in a catalogue that you blue-nosed Flemings can only envy and disapprove of.

A vacation from dalliance comes to me with the visit of Harry Luce and Bill Whitney over Xmas.12 I have just trod the via dolorosa of Roman pensions (unprecedentedly overcrowded) and finally found them a room-and-pension for 25 lire a day—less than a dollar in present exchange: Within stones-throw of the house where Keats died (little as that will mean to them!) and the College of the Propeganda of the Faith13 (little distinguished in your mind, you Calvin, from the Inquisition and other practices of the Whore of Rome,14 about which you have only the vaguest and most superstitious of ideas). This last thought of mine is so important that I am going to drag it out of brackets and continue it, by belaboring you for your ignorance and prejudice before the most beautiful religious system that ever eased the heart of man; centering about a liturgy built like Thebes, by poets, four-square, on the desert of man’s need. You and I will never be Roman Catholics, but I tell you now, you will never be saved until you lower your impious superiority toward this magnificent and eternal institution, and humbly sit down to learn from her the secret by which she held great men, a thing the modern church cannot do; and a church without its contemporary great men is merely pathetic.

¶ Charlotte is spending Xmas with the Blakes15 in Florence, I hear, then coming on to me. I receive this indirectly. ¶ Don’t acquire a barbarous lowland accent to your French. ¶ I’ll try and pick you up something for Xmas, though I must borrow to buy it. ¶ Tell me any intimate dope you may get from America on our parents; Mother’s letters are delightful quiet dining-room table affairs, and Father’s are trenchant homiletic. It’s foolish to expect other people to write as revelatory letters as I do, but I wish that they’d at least intimate the alternations of climate in their minds and hearts. ¶ I’m not at all sympathetic with your shockedness over fellow-students conduct: you haven’t learned Morals, you’ve learned the Code of Morals. Politeness and Celibacy are a matter of indifference to God. Go deeper. If possible, sin yourself and discover the innocence of it.

love

Thornton

Accademia Americana

Porta San Pancrazio, Roma

Feb 1, 1921

Dear Papa:

I have been shamefacedly conscious all these last few weeks that you were just about to receive, or had received, an ugly-toned letter from me. I would give the world to recall it, especially now that your beautiful grave reply has come. Now I am conscious that you are receiving two more “financial” letters, not bad-spirited I hope, but violent and despairing. You see the date on my letter and will be glad to hear that I have payed my January bill with a little help from a discreet unexpected source, and can now live weeks and weeks without raising my voice. The whole original trouble lay in the fact that I did not realize my monthly Academy bill was £500 (now £600) and that my original Express checks gave out soon after I arrived in Rome and could no longer eke out the transoceanic remittances. I think I have now learnt how not to spend lire; and am out of the danger of ever exhibiting myself in such a disgusting uncontrolled state as you’ve had to look at lately.

Just the same I’d like to go away from this crowd about Easter time. My two courses in Epigraphy and Roman Private Life will be finished by then, and I think the new one, Numismatics. They are full Post-Graduate School courses, and although I have groped, and scrambled and lagged behind the PhD fellow-students I think I can get the professors to sign a little document to the effect that I passed the courses. Teas and dinners increase, and I hope it can be said I have improved those opportunities too, but I would be glad to leave that. There is only one friend I shall greatly miss. The dim churches, the pines, the yellow sunlight you will see in my eyes for years—it doesn’t matter when I leave them. I should like to leave for a week or two in Florence and the hill towns about the middle of April—then up to Paris until sailing home in late June,—either by the Fabre Line again from Marseilles or if I can find one cheaper from northern France.

In imagination I hear you quite clearly wondering reproachfully why Thornton—in the middle of great natural beauties, amid masterpieces, with a great deal of free time, well-housed and fed, among friends—shouldn’t at least be docile and simply grateful. My only answer is that the very complexity of things flays one’s peace of mind to the point of torment. You are haunted by the great vistas of learning to which you are unequal; continuous gazing at masterpieces leaves you torn by ineffectual conflicting aspirations; the social pleasures and cheap successes bring (against this antique and Rennaisance background) more immediate revulsions and satiety. A snowy walk in Mt. Carmel, Mother’s sewing and you with your pipe hold for me now all I hold of order and peace. Your queer “aesthetic” over-cerebral son may yet turn out to be your most fundamental New Englander and most appreciative of the sentiment of group; when Amos and Charlotte have set up independent self-centred institutions, I shall turn out to be a sort of male Cordelia!16

Your enclosures give me the keenest pleasure. I miss only one sort; the “Alumni” and newspaper reports of your recent speeches. I am very pleased and proud of all these menu-cards and the letters that come in to you. I can’t have too many of these, and am jealous of every one you sort out into Amos’ or Charlotte’s mail: if I can’t claim a great part of the inheritance of your patience and sublime endurance (virtues you have consigned to my light-haired fellows) I can at least rush forward and stake out reflections of your animation and vitality and (hear, ye Heavens!) your eloquence.17 You will always turn to find my eyes bright with delight and admiration at your wit and charm, even if I am occasionally (Oh, for the last time!) thoughtless of your sacrifices. And I can already see Amos and I, whiteheaded at the age of eighty, disputing amicably as to which of us knew you best, Amos who could not take his eyes off of your labors, so beautifully and quietly sustained, or I who was always after cajoling you into those moods of quickness and inspiration that you were allowing to grow less frequent. Either aspect alone could make the reputation of a great father, but with both we have a right to feel a little bewildered and hide ourselves from the responsibility of standing up to so much privilege and love. Here I am, a sort of Arthur Pendennis,18 breaking down in front of you, and wishing old words unsaid and old silences forgotten, and remembering you so intensely as you were when you came to Litchfield, or to Mt. Hermon, or to the Duttons’. I hope this letter will get to you at about your birthday and if you sit down on that day to think us all over, I hope it may lift from my record some of the discredit left there by my last three letters.

Much love

Thornton

Accad. Americana

Roma: Aprile 13 1921

Dear Mother:

I have just sent off letters to Father and Amos, and feel so virtuous that I must write you two<too>. I left you after my last, hung up in suspense over my luncheon at the De Bosis.19 It fell out almost as I anticipated, only twice as delightful. The reddish-yellow villa, hung with flowering wistaria at the end of a long avenue of trees; choked garden plots with various statues of Ezekiel glimpsed through foliage; the rooms of the house furnished in rather ugly Victorian manner—all modern Italian taste in music and art being deplorable, perhaps because they are so discriminating in literature. Some guests, a young Englishman named James; a Miss Steinman; the young Marchese di Viti whose sisters I had met, a beautifully bred discreet medical student. Signor de Bosis himself has a sort of abstracted gently humorous air, silent, that sits agreeably upon one who having so many over-intelligent children doesn’t have to descend into the arena of conversation very often, and then only to kill. These days—perhaps I told you—he is revising his verse translation of Shelley’s The Cenci for immediate performance by Italy’s foremost company now in Rome. He is one of the best Italian poets (conservative) and as such made an address in the Protestant Cemetary on the anniversary of Keats’ death last month. [Upstairs he showed me his recent discovery of the meaning of the first two lines of the Epipsychidion, and if you turn to the lines you will be glad two <to> find that the Emilia Viviani’s sister spirit is not (as she herself thought and Ed. Garnett) Mary Wollstoncraft, but Shelley who puns here on his name Percy—in Italian “lost”—as Signor De B. found in a few casual lines where Shelley began translating his poem into Italian.]20 At table things went merrily in and out of both languages. Lauro—my friend—and the Arabic-Arimaic sister I admire, so began throwing at each other in latin and from memory the ridiculous list of beautiful books which Rabelais says Pantagruel found at the library of Saint-Victor.21

I went with some of them last night to the last Symphony Concert conducted by Arthur Nikisch; the program was “popularissimmo” Beethoven’s Egmont and 5th; Lohengrin and Tristan and Tannhauser Overtures and the Liebstod, but I have never heard such conducting in my life. ¶ Signór de Bosis has sent me a book of his verses inscribed. ¶ I have found an Italian playwright whose plays I adore, the Sicilian Luigi Pirandello. Philosophical farces, actually,—strange contorted domestic situations illustrating some metaphysical proposition, with one eccentric raissoneur in the cast to point out the strangely suggestive implications of the action. The very titles evoke an idea of his method: “Se Non Cosí” “Cosí è (se vi pare)” “Il Piacere dell’ Onestà” “Ma non è una cosa seria.”

¶ One of our boys here is developing such serious hallucinations that he may have to be treated for madness. He is insanely in love with a lady more clever than considerate, and altho’ she is away fancies her arrival momently, prepares imaginary teas under the delusion that she is arriving, rushes out as each streetcar climbs the hill. He fancies also that she is just around the corner but refuses to come in, that she stands evening-long under the arc light opposite gazing at his window, or prowling about the iron fence of the Villino Bellacci. By an impossible chain of logic he fancies me in league with her, dictating letters for her to have mailed from Siena (where she is in fact) while she obscurely fixes her gaze upon him in Rome. I no longer try to reason with him; (as Freud will tell you) the idee fixe is only agravated by contradiction. The woman is a pure adventuress,—like the woman in my play strangely enough, a Bohemian countess.22 ¶ I had myself a strange little sentimental experience that made concrete the warnings that Continental women however impersonal, comradely and full of good sense they seem, cannot understand friendship that is without romantic concommittants, cannot, cannot. Queer!

love Thornton

American Express Co. 11 Rue Scribe Paris

June 27, 1920<1921> Sunday

Dear Papa:

A letter came from Mother dated June 1, Mt. Carmel, giving me directions to write her at the boat’s landing Southampton. But it only reached me on the 16th and I could never meet her then, so I await further addresses. People about here are full of the delays and losses of mail in the American Express Co; I hope I am missing no one’s letters altogether.

Well, I have begun conducting a column in the Telegram called The Boulevards and the Latin Quarter. It takes no time to do it and I am already following up openings that lead to jobs to combine with it. But there is so much “call Thursday, if you can. Mr. Y will be here,” calling over and over. If I get enough of these, I hope you will approve of my staying until Xmas. I am making as little inroad as possible into the money that is understood to be my passage money. I have still over 1500 francs there, and if the readers and advisers of the new Telegram write in that the chatty theatrical column is an ornament I shall be taken on regularly and perhaps given more—interviewing and so on. In the meantime I am provided with addresses of American movie people who want someone to write cinema “titles” etc.23

Don’t worry or think about me. I wear clean linen, brush my teeth, “hear Mass” and drink much certified water. Without sticking to Americans I meet many people you would like to feel near me in ambiguous Paris—Mrs. Sergeant Kendall, for instance. Polly Comstock (of Trumbull St.) asked me to lunch at her pension the other day, and there was a Mr. Winslow of Madison who remember<s> me as a baby. I couldn’t tell him that Mr. Cushing and himself were the two people always held up as object-lessons to avoid. Bill Douglas is here, too.24 Steve Benét returned to America, but will be back in October. I have met his fiancée here, a journalist on the Tribune.25 She has made him give up drinking so, or almost. Mrs. Wells is here, though I haven’t seen her yet. It seems quite true that Danford Barney26 is incredibly mean and brutal to his wife. I ran into Frank Brownell of Thacher and his mother the other day; and a young Mr. and Mrs. Holcomb York of New Haven. I don’t know what’s become of Amos and Charlotte since last I wrote you. Charlotte hasn’t even acknowledged the receipt of the twenty-eight dollars which vexes me: I have all the receipts however.

I buy little penny paper copies of the great French classics and read indefatigably, but I am increasingly at a loss how to find opportunities to speak French at <a> stretch. I go often to the clubrooms of the American University Union and there are some notices hung up there of students wishing to exchange hours with an American but inquiry at the desk reveals that the notices are months old and the requests long filled. This is something to worry about for me—since you must—and also about the difficulty of keeping one’s stomach working regularly. And the distastefulness of having to go to public baths for one’s shower; a vulgar practice that I resent, universal and respectable though they are over here. I am often homesick for America or Italy. The Frenchmen are not so immediately “sympathetic” as the Italians, and I am eager for letters from you and mother. I should like to know if the Mt Carmel house is given up, and if you are left to the depressing emptiness of Taylor Hall.27 I hope you have made a homely room in the Graduate Club,28 with your photographs, Thoreau, and the neckties (from which Amos and I long since rifled the best) about you—I remember against the wall, too, long envelopes bursting with matter that I have always supposed to be your notes on the years in China. They will be in your new room. A cup or two of Amos’s.29 You may feel quite free to smoke, too, for even if it’s example should penetrate to me, it would do little harm for I don’t finish a cigarette a week. An arrangement so that you can read in bed, read Walpole and Burke and Mrs. Montague and Swift—all the inexhaustible standards that wait for me someday when I have lost both legs in a streetcar accident, and need stout trenchant reading. Copies of The Literary Digest and other sources to transmute into public reflection.

You see I wish you happy. When you have counted your troubles with a certain Puritan satisfaction in the reflection that the Inexplicable Disposer of Things has thought you worthy of trials beyond the endurance or even sympathy of most men—leave me out. Consider me as some other man’s son, strange and remote, loving you at that distance prodigiously and unaccountably.

Thornton

269 Rue St. Jacques. <Paris>

Thurs. <August 1921>

Dear Mother:

I’m so amazed I don’t know what to do! All the millions of French books I’ve read this last year haven’t helped me the slightest in speaking or in grammar? However I am bold to bluff. I rushed right out to take a lesson every day with a certain lady who has been taking my fellow-pensionairres; she will supplement my forced marches through grammars at home.

I shall come over and see you very soon but not until the day before my mois30 is up here—money must be saved at every corner, and although its worth a hundred dollars that I should see you again before going back, it is hardly worth ten that I should see you seven days instead of six. So I shall probably come over—following your directions—the night of the 26th of August. More later.

Let Isabel be very cautious about her movie course. The magazines are flooded with inducements to take courses. Let us talk over.31

I shall try and see Aunt Charlotte tomorrow morning, although I have heard no word of her.32

I have not cashed the money yet but am sure it will go through as quietly as the other did. ¶ A letter from father Aug. 1. in which from what he says he seems not to have received my cable YES nor my S.O.S!

Lawrenceville you know is the smart prep. school for Princeton and entertains only big husky team material. Oh, how well dressed I must be! I’d better grow a moustache for maturity.

Well, well, I’m as excited as a decapitated goose. Will see you soon. I might perhaps get a later sailing but I’d rather not and I dont think Father’d mind, since my stay has been a month prolonged as it is.

None of you say how you like London. It has finally broken into Rain here and the whole world seems better. You must polish up your French and find a neighbor or two, a French maid perhaps who will sit on the area steps with me gently exchanging subjunctives.

Isn’t it perfectly mad of Father; but it’ll be awfully good for me in the long run.

Love to the whole caboodle.

Thorny—soon

Oct. 3 1921

Lawrenceville

Dear Father:

I didn’t realize until I got your letter, on returning from Trenton that the suit and the other obligations were to be separate. I didn’t send you enough, of course. So I am enclosing the first of my checks. Will send on more whenever you say.

I hope they can cash this for you without delay; otherwise let me know by card and I will send you the same thing by postal money-order.

The work goes on by strange ups-and-downs. The heart of the matter is that no amount of good intentions or mental coercion can really bring my interests into our table conversation, our discussions of verbs, of athletics. I am still in Europe. I especially cannot forget Italy. The boys see instinctively that I am not the collegiate live-wire.

But then again—especially mornings before I am tired by the awful excitement of dragging a class through the iron teeth of an assignment—I seem to be irresponsible and “good fellow” and we exchange the expected breakfast remarks with all the spontaneity in the world. There are a number of boys in the house for whom Mr. Wilder is quite an adequate Assistant House Master. I get on well with Mr. Foresman too, but I suspect he regrets not have<having> the vigorous snorter assigned to him.

There are times of great pleasure in the class-room when I know I’m not merely adequate, but really good. It only took me a day to reach perfect composure; I usually stroll about if a class is reciting well directing olympianally now from the side now from the back. With my older class—we are reading a French classic—quite unconsciously I get drawn into some exposition of idea or technical expression—and I suddenly think that that art of holding twenty intelligences in hushed attention is going to justify my coming down here in the capacity of unprepared teacher and unsuitable companion

—afftly

Thorny

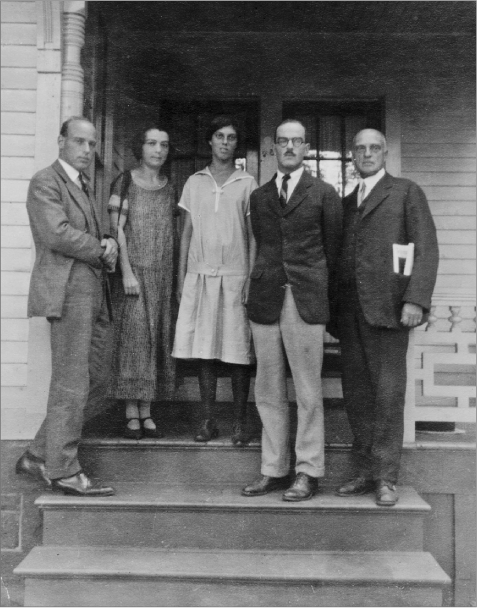

Davis House, Lawrenceville School.

Davis House, Lawrenceville School. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. 151

<Lawrenceville>

Nov. 4 1921

Dear Dr. Wager:

Four evenings a week I sit up in my study from seven until ten while my thirty-two boys do their preparation for the morrow. They begin to drop in, a difficult phrase in Caesar, a little Trig, “Please, sir, what does mendacity mean?” some French, a little chat, “would you like some fudge my sister made, sir?” Every now and then there is a sound of scuffling on one of the three floors. I rise, and descend the stairs with majestic and perfectly audible advance, dispensing awe and order like fragrance. Finally fifteen minutes freedom before lights-out; sudden activity, four Victrolas play, rushings to the bathroom, four-part harmony. Then the last bell and I lower the lights. An expensive benevolent peace invests us; my heavy reconnoitring footsteps flower into symbolic significance as I lock the backdoors and try the windows. Follows about ten minutes of furtive whisperings from bed to bed, and they fall off to sleep—most of them having sustained the incessant impacts of football practice throughout three hours of the afternoon. People said to me Never teach school, You will be so unhappy, It will deaden you. But what happy surprises you find here; how delightful the relations of the teacher and an interested class; casual encounters with retiring boys on the campus, and at lights-out the strange big protective feeling, locking the doors against dark principalities and powers and thrones, and the great lamp-eyed whales that walk ashore in New Jersey—

Thornton

Davis House

March 4 <19>’22

night

Dear Father:

I wish I wrote you often. My natural inertia is now fortified by my professional lack of quiet time, and I write even less often than before. ¶ It is agreed that I am to stay on here another year. I had no way of knowing whether I “suited” or not,—at times it seemed to me that the Headmaster loathed me, my housemaster longed for a change of assistant, and the boys on the point of petitioning my removal. But these must have been phantoms of an (at times) overworked nervous system, for the day, March 1, when you must announce your decision about next year, and when—so says the contract—the H’dmaster must announce his objection to you, if such there be, has gone by. Mr. Foresman was amazed when I told him that I had expected to be called into the Foundation House, told that I was an entertaining guest but that they required a more athletic type. He told me that I was considered a pearl of great price, that he for the first time felt secure about the house when he was absent, and that if the vote of the boys counted for anything I had reason to feel signally pleased. There is a considerable amount of double-reading in all this that mitigates its flattery, but on the whole I feel like one who has come out of a perplexed bad dream into a more confident waking.

My little English Club is coming along in the most delightful manner. The boys read very earnest bad original poems to oneanother. We take, eight of us, walks through the bare tree trunks of a hesitant Spring; its really too easy for me—imaginative boys from homes and schools that never fed an imagination—my flattest remarks on books or style or even people are manna to them. I’d like to give you all their innocent names if I thought they would evoke for you as they do for me, the awkwardness and charm and rush of their opening minds. ¶ We have almost found, you and I, that, with food and shelter, I can be happy almost anywhere. If the Amherst offer comes after all, and now I can no longer accept it, without doubt it indicates a scene where I might too have been happy; but not happier than my second year promises to be. Now I have learned some of the principles of teaching, now that I have mastered all but the obstinate core of the problem of classroom discipl<in>e (the core—those one or two fundamentally bad boys who are bored and restless and vindictive anywhere except in a pond of mud); and that I have made many friends and got over my worried distressed eager-to-please attitude,—I look forward to reaping a harvest after my real labors of this year.

Will you send an occasional letter of mine to Oxford. I write to the mad air-fed ladies every now and then myself. To you I can write hurriedly, between bells, but to them I compose like an artificer, and the result <is> I write them with despicable infrequency. Keep urging the wild witch Charlotte to tell me how it goes.33 ¶ If I save hard, am I justified in looking forward to months on it at Monhegan this summer?

love from

Thornton

Box 282, Newport, R.I.

August 3, 1922

The Editors of The Dial

152 West 13th Street New York City.

Dear Sirs:—

I am submitting under separate cover the MSS of a series of imaginary memoirs of a year spent in Rome, entitiled The Trasteverine. These give the appearance of being faithful portraits of living persons, but the work is a purely fanciful effort in the manner of Marcel Proust, or at times, of Paul Morand.34

Attached hereto find return postage.

Very truly yours,

Thornton N. Wilder

Box 282, Newport, R.I.

August 22, 1922

Dear Mom:

I have told the family where I tutor that I must go away Friday; so now I give a lesson every day and am a solid fellow. In the afternoons I take the ferry to Jamestown, walk out to a remote point of land, so far from the World (that father cannot get over his fear I am in town to cultivate!) that I need only wear the trunk of my bathing-suit. Here I read and read, exposing myself to the ultra-violet rays of the sun that give me a thorough sunburn. Every now and then I plunge in and swim a big arc, then come back to read some more. The other day as I was just about to enter the ferry on my return a boy came running out of breath to shake hands; a Laurentian whom I didn’t remember from Adam, but an auspicious beginning of the new year.

There is a new, very radical magazine, called the Double Dealer, published in New Orleans, that has accepted two “Sentences” of mine, drawn from the Roman memoirs. I’ve never even seen a copy of the paper; but will forward all to you when it comes out.35 “The Dial” a very high class, though ultramodern, review is flirting with the publication of the whole Memoir. I only sent them the first book, ten or twelve thousand words. They write back that it is hard to estimate a fragment, that some pages are interesting, and those that aren’t may be so because of their relation to the unfinished whole. They enco<u> rage me to send them the rest. Well, I can hardly send them books seven and eight when I have not begun Book Two. And I am unwilling to kill myself with the composition of an interminable Book Two without still greater assurance of their using it.36

You remember that I told you how when I met Mrs Augustus St Gaudens in Rome? She confided to me that her son, Homer, the stage designer, was engaged in dramatizing General Ople and Lady Camper, a long short story of George Meredith, for Maude Adams, their very good friend.37 I suddenly became curious to see it and send<sent> to Trixie Troxell,38 my friend in the Yale Library, to send it to me. It is quite amusing, but utterly unsuited to stage arrangement; and the idea of Maude Adams as the sophisticated dictatorial Lady Camper is the crowning absurdity. Since then I am mulling a play about the riotous character of the Countess of Saldar in Evan Harrington.39 I tell you all these tentatives because it may set you reading the old books to distract your mind, and because even as unfinished impulses they might interest you.

The fleet has been in the harbor and the community is after giving them a block dance. A stretch of well-paved Washington Square, as wide as the Yale campus and twice as long was roped off and sprinkled with corn meal. The moon was shamed by strings of colored electric bulbs and by batteries of searchlights with petticoats of amber gelatine in front of them. Up until eight oclock a twenty-foot hem of craning citizens was held back by the police, while in the center of the naked acre on a few precarious chairs sat the patronesses, Mrs Admiral Sims, the mayoress, and some ladies from the Summer Colony whose closest connexion with the navy resided in the fact that they were great-grand-daughters-in-law of Cornelys van der Bildt,40 the ferry-boy of Staten Island and pseudo-commodore. The grand march was so long that it reminded me of the armies of David Belasco41 where, as soon as a soldier passes out of sight of the audience, he rushes around behind the scenes and re-enters on the other sight<side> as some one else; it was headed by a great deal of gold braid and brought up by a million gobs and their girls. There were two alternating bands composed of musicians off all the cruisers and very good they were too. I went and stood near them to subject my deliciously suffering spine to the rages and hurricane of the great brasses; just as in Rome (when the lira was at twenty-eight) I would get a seat for Verdi’s Otello fairly on the percussion, so that during the Taking of the Oath at the end of the Second Act my nervous system might happily be reduced to rags. Someday I shall take a camp stool and sit inside the bass drum during a performance of Elektra.

You will have a great headache from seeing all these misprints. I will close by saying that I shall not be able to see Charlotte after all; she is gone on a few vacation trips until the thirtieth. I take the night boat for New York Friday night and will be with Father Monday morning to help him on the Journal Courier for two weeks while he goes to Maine. I don’t know what he thinks I can do, but I am willing to try. Love to you all, named Wilder and to Aunt Charlotte. I am eager to hear anything you can snatch time to say.

love

Thornt

Davis House Lawrenceville NJ.

Sept 19 1922

Dear Mother:

I must write you something at this psychological moment. This is the first night that the boys are back in the house. Mr Foresman is away at committee meeting and I have just turned out the last lights. A most well-omened silence wraps the house. Thirty-three heads have fallen back on their pillows as though they had been chopped off. The excitement of arriving and shaking several hundred hands has fatigued them, just as football practice and Latin will next week. There are a dozen new boys in the house and of course we are all looking each other over furtively. There are almost a dozen new masters in the School, too, all young but three. They come from all sorts of backgrounds and are much shyer than even the new boys. Mr. and Mrs. Foresman, with whom I live are looking well; he is a little stout man, an old football celebrity, with blunt ideas and a jovial reticent manner; she is much superior intellectually, a Cornell graduate, but domesticating rapidly—her not inconsiderable good-looks gradually approaching the benignant maternal. Her French and Latin are in astonishingly good repair, and we play piano four-hands after a fashion. The baby Emily, age three, is a squirming little girl with a piquant French face. Contrasting though we are, Mr. Foresman and I get on finely. I often think that the reason I have got on in the House so well, is because his personal affection for me is always forseeing and averting things that might embarrass me. The result is that I am being extremely well paid for being happy. In return fortunately I am able tacitly to help him; today, for example: Mr. Foresman has a horror of meeting the fathers and mothers and making conversation. Consequently in the face of express orders from Foundation House to stay at home, he drives off to Trenton, and leaves to me to a dozen fascinating encounters with mamas depositing their sons in our spiritual Pawn-shop* Human nature is often as simplified as the comic supplements represent it: I have had exactly twelve proud, deprecating, anxious accounts of some priceless sons. The same apology for their inability to study, the same confidence that the fundamental gray-matter is all right, the same anxiety about blankets.

I have written now into profoundest night. The last mattress has creaked, the last slipper flopped back from the bathroom, the last yawn-blurred words between room-mates, exchanged.

lots of love

Thornt.

Dear Mom:—

I forget whether I sent you a copy of The Plain<Double> Dealer, so if I send you another put it down to utter indifference to the honor of print, rather than to pride. I shall send you Lefty’s novel42 too, when I can get into Trenton. You should see my room. I got an introduction to a department store and started shopping on account. Two deep blue rep curtains as a portere between my study and my bedroom (there was a dusty red thing there last year) two deep blue strip rugs crossed the empty bit of floor by my desk, a really beautiful blue, without design except for two inches of still darker blue around the edge; and white curtains for both windows. Vous m’en direz des nouvelles!43 I just controlled myself from buying one big deep blue rug a foot thick, that would pervade the room and (being a little too big) would turn up to climb the walls for about an inch all around, like the toe of a Turkish slipper. I have a big rectangle of blue cloth that says YALE on it, but it seems to have been lost over the Summer; it was to be, of course, the keystone of the decorative plan!

I am to teach 24 hours this year, if there is still pressure on me to take an hour of Bible. Naturally with such a load I don’t have to take any Study hour supervision in the Big Study (that I am very glad to be out of). I have no 1st Formers to teach, though I was supposed to have shown some aptitude for the wrigglers last year: instead I teach a 2nd 3rd 4th and 5th—these last two mature ones are, of course, my dulce decus.44

I am fashioning a new 3-minute playlet, very strange called And The Sea shall give up its Dead.45 which I shall send you, if it comes to anything.

Excuse now if your grown-up and busy son rushes away to help boys arrange their schedules to direct tramping negroes on the stairs as to the destination of trunks, and to brush the teeth of his thirty three stoopids. Love to Isabel, who may find an outlet for herself and a chance of helping Charlotte enormously on that page of the Youth’s Companion.46 I’ve just about broken my neck looking around for something else odd to send Janet, but I swear there’s no originality in our shops. To Amos a salute, as we may be on the brink of new wars, wars in Palestine too for a generation that can see no irony. love

Thornts

Davis House, Lawrenceville, N.J.

Oct 9, 1922

My Dear Mrs. Wilder,

Your son has asked me to write to you in his stead for two reasons. The first is that he is so ashamed of not having written you for so long that he has no idea of how he should begin. The second is that since you have never received a letter from Lawrenceville written by anyone except himself, you might enjoy someone else’s view of the life there. I am not only in his house, but in two of his classes and can give you some idea of how he appears to us.

If you are going to excuse his silence, it will be a shear act of grace. It is only fair however to tell you the few arguments he might put forward. He teaches twenty-four hours; most of the masters have between eighteen and twenty-three. The correction of papers for so many is enormous, to say nothing of the tiredness that follows it at night. Besides just as he was about to write you last week something urgent arose. One night while we were at supper I was bidden to answer the telephone. It was for him—a long distance call from New Haven. When I told him they were waiting for him, he changed colour, dropped his spoon into the soup, and ran. It turned out to be Mr. De Lacy of the Brick Row Book Shop. Mr. Hackett had been struck by an editorial in the Journal-Courier during the Summer on the Shelley Century, and had called up your husband, thinking he had written it. Dr. Wilder redirected him to your son. They wanted a longer article in the same vein, to be printed in the Yale Alumni Weekly as an introduction to the collection of Shelleyana they were offering for sale shortly. The collection was to include a locket containing some of the poet’s ashes, set in fourteen aquamarines and listed at three hundred and fifty dollars, a beautiful portrait of Mary Wallstonecraft Shelley, for the first time drawn out from the obscurity of a private collection, and many first editions. The Book Shop assumed that the article would be a labor of love, but would instruct its treasurer to mail him ten dollars. This was Thursday night and the material must be in New Haven Monday. The school pressure was hard enough without this, but he undertook it. He has intimated that if the article is printed in the Weekly and meets the favor of such Tinkers, Phelps, Berdans,47 as have hitherto watched him but doubted his adequacy to conventional tasks, like that, it might lead to offers of college teaching. Again, it is probably a delicate sounder from the Book Shop that has now three branches and is looking for cultivated young men to station at their outposts. At present he feels disinclined to join either connexion, but he would like to have them offered to him. The finished essay was amusing, although it had serious weaknesses of structure. To me it has a tremendous air of learning, though Mr. Wilder says that is merely the result of a hasty pillage of some source books that can be found in any good library. It is not unlikely however that the article will not suit the requirements of the Book Shop; it does not go into ecstacies over the brooch filled with ashes, and a repulsive portrait of Shelley (companion piece to that of his wife) is given a cold notice. Everybody knows that the Brick Row Shop has grown more and more bloodlessly financial, and the economic interpretation of your son’s piece is temperate; he refused to boot-lick. However, it is at least suave; they may have to use it for lack at that eleventh hour of other material. If it goes in, he is almost certain of its attracting notice. In parts it is green, but in others it is trenchant and witty with his characteristic precision of words tempered of late by his much French reading.48

We get on very well with him in the house. He almost never interferes with us, and we do not play dirty tricks on him like they do in other Houses. He doesn’t come out and watch our football much, but perhaps if he were the kind that did he wouldn’t be able so well to help us in Latin etcetera. In class he talks so fast and jumps on you so sudden for recitations that often you don’t know a thing. Please write him for his own good to speak slowlier, as it would be for his own good. Of course this year he is an old master now, and has the hang of keeping a classroom down and never has to give marks, any more, or even fire us out of the room, like new masters do. He must have learnt summers somewhere. Can you explain why he hasn’t any pictures of girls in his room, nor even of you, everybody has pictures of women in their room, can you explain this? Why did you give him a name like Thornton for, didn’t you know it would be a thing we would hold against him, you might have made it Theodore through<though> even Theodore is bad, and Bill or Fred is best. Don’t think I’m crabbing, because after all he’s all right for the present and you don’t expect a master to be everything. He says he has some sisters, are they good-looking, or are they like him, and nothing can be done about it. Thanking you for your patients, I am

faithfully yours

George Sawyer Naylor.

Davis House Lawrenceville N.J.

Feb 10 1923

Dear Mama:

Your wandering boy tonight is very contrite. If Father however forwarded to you my playlet, as I bade him, let me count that as a letter, and the case is a little less damaging.49 My letter before that described to you my Xmas vacation. Since then I have lain very low in Lawrenceville, teaching without respite. Last Tuesday however a fellow-Master, Mr. Rich, two faculty ladies and I acted Barrie’s The New Word50 before the Woman’s Club. This choice one-act play was in the volume Isabel sent me a year ago with the inscription “bought in a shop in Tottenham Court Road.” We are to repeat our performance Thursday night in front of the boys, our most exacting public. I am including a review I wrote of our student Dramatic Club’s latest effort.51 So much for “events.”

Isabel’s letters from Paris to yourself, to Father, and to me—I receive them all ultimately, are absorbing reading. My stomach faints with emotion at the very address: 269 Rue St. Jacques. I expect I shall have saved enough for a trip by this Summer, but I am afraid to use it. Any sums I may be able to put by (and even such will be less than a thousand) will be too valuable as a resource for us Wilders and I do not want to touch it until the year following. No doubt you are astounded to notice this touch of avarice; but believe me, I am a very naughty boy and the reverse of avaricious. I am just about agreed to join one of two Summer Camps that are angling for me—to do a little French tutoring, spend the days in a bathing-suit under breezes smelling of the pines, with almost no fixed or disciplinary duties. There will be a considerable interim at the beginning and end of the Summer, and generous leaves of absence during it, so if you are back here I shall <be> transported with joy and at your side. Father says the Adams are urging you to take their house for the Summer months, and in combination with the reduced fare to Mamauguin52 it seems a good start. Turn it over for yourself however, carina53; I’m behint you.

Great long stretches of my Roman Memoirs are now done, and I’ve a good mind to group together the Society sections and try and send them out into the world first, under the title: Elizabeth Grier and her Circle. To many readers they will seem (this show of the low-life and ecclesiastical material with which in the ultimate version they are relieved) too gossipy and feminine. Many passages however are of a valuable mordant satire, and others drenched with restrained pity; I am not ashamed of it. You would be a great help, but I cannot send my forlorn unique text across the ocean.

Charlotte’s essay in the Atlantic54 has made a pretty stir in Lawrenceville. She has been sending me some sonnets of her writing that will make you hold your breath. If she keeps on right she may discover herself as something of a very high order that will scatter our magazine poetesses, as a hawk does the hens. Don’t say I didn’t tell you. What is the secret, madam, of having astonishing children? thousands of pretty, intelligent mothers growing old among their dull prosperous and un-appreciative sons and daughters ask you that question. Their life threatens to be a decrescendo; have you any advice as to how young mothers can guarantie themselves a crescendo?

Albert Parker Fitch55 of Amherst spoke at our School service today admirably. I met him here last year and twice this year; Stark Young56 had told him about me too,—we had fine talks. He spent the Summer at Fiesole in perfect quiet at a nuns’ nursing home. I have a letter from Gwynne Abbott57 full of how charming you and Isabel are. She has gone on to Merano in the Tyrol.

Anybody care to know what I’ve been reading. I’m now in the XIII’th tome of Saint-Simon,58 more adoring than ever. This influence, believe me, arrived most à propos—henceforward whenever I am endangered of falling into silken felicities and jewelled or flute-like cadences I have only to remember this memoirist whose three greatest virtues are energy and energy and energy. I have just read also “Siegfried et le limousin”59 by Giraudoux which I like for the rather weak reason that it is interested in the same things that interest me. The second instalment of your Xmas present has come and I have just derived a vast amount of pleasure from Doormats and Outcast. Who is Janet that you mention in your letters? some Y.W. worker doubtless; you say she enjoyed The Mollusc—send me a photograph.60 I can’t abide women who aren’t pretty; must I advance money for milk baths and electric exhilirators to make her more presentable? Is she by any chance interested in horses? When my book’s published, and I’m very rich, I’m going to live in the Connecticut hills and own a large stable of horses that can tell time and play bridge etc. I shall need a capable women <woman>, sympathetic (and pretty) to put over them. If you know anybody who might suit, have her write me at once and enclose a photograph. You can see how my ink is turning quite red with eagerness, and quite illegible with fear that such a valuable woman can’t be found.

—Quite a time has gone by since I began this letter and I want to add that my Eliz. Grier and her Circle is almost finished—watch and pray

love from a drying aging schoolmaster

Thornton

<Lawrenceville, New jersey>

May 3 1923

Dear Mrs. Isaacs:

Please take your time over the four acts I sent you.62 When reckoning comes do not spare me: I learn meekly. Besides they are from a closed chapter; after them came Dada.

Last night I shook hands with Max Reinhardt.

In the summer of Sixteen I spent a week on the lonely island of Monhegan, off the coast of Maine. In the colony of surf-painters and solitaries, human sea-gulls, that such an island would attract I frequented a group of Germans that gathered every evening in the draughty pine-board studio of I no longer know what musician, There was Herr Doktor Kuhnemann, University of Breslau, author of a standard life of Schiller; a Fraülein Schmidt or Müller, head of the German department at Bryn Mawr or Smith (one could verify these in an hour); and a Viennese dramatic critic named Rudolph<Rudolf> Kommer, who answered with unfailing good humor and wit my thousands of questions. Even while I was on the island I heard that the group was suspected of espionage, but, after I left, my Aunt says they were convicted of midnight signalling to a submarine base nearby, and interned. All these years go by and I see in the Sunday Times of two weeks ago that the article therein on Reinhardt is by Rudolph<Rudolf> Kommer now travelling with him as interpreter and agent. Just after I had made my plans to go to The Cherry Orchard in Philadelphia last night I saw, again in The Times, that Reinhardt was running down from New York to see the same performance. Sure enough, at the close of the first act, there he was in a stage box (with a gloriously beautiful actress setting off her face with the waftings of a huge feather fan in Paris green), and there behind him sat Rudolph<Rudolf> Kommer. They did not leave the box until the next intermission, when I pushed down the alley. Kommer was very cordial; declared that he had been wondering how he could find me, etc. He introduced me to Reinhardt, with a rapid, “nur als knabe er kannte mehr vom deutschen Literatur als die meisten Deutschen.”63 You know that the producer is astonishingly young and homely, but with bright eyes, and with a pretty, deferential manner. After a few polite changes, he said in good English that he was with a lady and must go; and went.

Kommer then said that it was all settled that he would return for production in the Fall; that he would begin with a big pantomime spectacle (though he is no longer fond of them); and that he ultimately hoped to do Strindberg’s The Dream Play and Shakespeare. He is excited about America, stunned and bewitched by the Ziegfeld Follies, and by the negro entertainers (he mentioned The Plantations). Kommer said that they had been to many plays and that Reinhardt was always pointing out actors in roles of fourth and fifth importance who were full of possibilities; he added that some of the actors for his Fall season were selected already.

Perhaps you have met them yourself these days and know a great deal more than this.

In the afternoon I saw Henry Miller, Blanche Bates, Laura Hope Crews and Ruth Chatterton in The Changelings a jumbled comedy by a New Haven friend, Lee Wilson Dodd; a quilt of contrasted intentions—ten minutes of drama about misguided ladies stealing to bachelors’ apartments; sudden rush for chairs and a poor Shavian badinage about morality; Blanche Bates suddenly turns farcical and does Hermione64 (just before the curtain she will return to her Noble Mother tune); stretches of preachment about pretty wives who shirk light-housekeeping and on studious young husbands who do not admit their wives into their enthusiasms and Ph.D. theses. Oh, how bad it was; even Laura Hope Crews was bad. And in the intermission Blanche Bates made a speech about how they all loved Henry Miller, how they knew they were out of the beaten track of the theatre, but that they were glad and proud to be with him, who had always led out in the direction of the Best Things in the Theatre …….. and Stanislawsky65 and Reinhardt both in town!

I should love to write you for seven days and nights, but I shall see you soon—unless you leave for Europe before the third week of June. You will have a glorious trip, but you will not regret too much arriving back in New York for the finest season in our history.

Give my very best to your husband and children. I hope I can see you when I come up from graduation, but I shall not force you to choose between me and Italy.

Affectionately,

P.S. I forgot to say that Kommer mentioned by name Bel-Geddes66 as one of the younger artists Reinhardt hoped to work with.

Davis House,

June 5 1923

Dear Mother;

Just a page to supplement the letters Father and Uncle Thornton wrote you about Grandmother’s last days.67 Father asked me if I could come up Sunday. I arrived at about two and turning into 44th St. from Broadway came upon Father leaning against the area-railings. He had waited in and around the hotel for three days, it seems, and was to be relieved that night when Uncle Thornton arrived on the midnight from St. Louis. He took me right up to Grandmother’s room, nodding to the various people in the lobby all of whom were very concerned. She had been moved into a larger and lighter room, with a big bed and was attended by a homely middle-aged nurse whom Father claimed to find “superior,” but who gained my confidence only by her stolidness. Father leaned down to Grandmother’s ear and said that ‘little Thornton from New Jersey had come up to see her’. She opened her eyes wide and I am sure she recognized me, for she framed with her lips the elongated O, and uttered the tremulous cooing noise with which she always greeted me when I knocked at her door for a visit. Father continued to repeat that it was grandson and not son Thornton, whereupon she broke into a musical but incoherent flow of words in which I read a reproach at his presuming her capable of such a mistake. Her words in themselves were clear and even beautiful; the difficulty lay not in speaking but in thinking. When after a few moments we made a motion to go, it distressed her, for she raised her hand and wrinkled her forehead in a characteristic expression of humorous reproach; so we sat down, until from fatigue or content she had closed her eyes and forgotten us. Somehow the interview was anything but painful; it seemed to breathe Grandmother at her best, sweetness and a touch of humor. Father has probably told you the many beautiful and characteristic incidents of the days he watched by her.

After that Father and I walked for a few hours in Central Park, and I left for School. I went up again for the Service on Thursday. There seemed to be quite a number of people in the Bible Study room behind the Church Auditorium (she and I had once sat there waiting for Church to begin). Father led me up to sit beside Charlotte; it had never occurred to me that she would be there and dressed in complete black. Dr. Kelman,68 whom Grandmother admired so and had taken me to hear during my Christmas vacation, the great Dr. Kelman, opened with a wonderful prayer; it wasn’t just good, for it was perfect. Then the Dobbs Ferry minister who conducted with him read some lines of your father’s that Grandmother had once found for him. Then just the six of us drove out to the cemetery, to the knoll amid countless columns marked Lewis and Nitchie.