March 23, 1943

Dear Montgomery Clift:

My sister has only just told me of your ill health. As grateful author I have the best of reasons for regretting your withdrawal from the play,94 but the important thing is that you restore your health before you have overtaxed it and that you restore it for a long and triumphant career in the theatre.

I hope you are going somewhere for a long rest under wise care. Do not trouble to answer this letter now, but when the convalescence is well on its way, I should be very interested to know what you are thinking about, what you are reading, and what you are seeing; (this last shows that I hope you are considering our Western desert country where most of the invalids I’ve known have got ringingly well—“seeing” means the profile of mountains around Tucson.)

Be patient in your resting. Give in to resting. Put the present agon of the world out of your mind—with the invalid’s legitimate permitted selfishness.—Read and think over only the works from which the stress has been removed by the author’s art—about suffering but not of it—Sophocles not Euripides; Mozart not Beethoven; late Shakespeare not middle.

Think of yourself as surrounded by the grateful thoughts of your friends—among whom i hope you count

Sincerely yours

Thornton Wilder

Last hours at the Billetting office, Air Base,

Presque Isle, Maine.

Hereafter: APO # 4002, c/o The Postmaster, N.Y.

May 21, 1943.

Dear Michael:

Try and remember at what moment you arrived at the point when you were unable to discuss the production with anybody.

It would teach you a lot about yourself, your past and your future.

What was the moment when you locked up your mind in a steel brace.—and transferred the operations of the reason over to sheer blocked unlistening will?

From that moment you talked like a hysterical madman,—building up exaggerations; contradicting yourself hit or miss; substituting wish-fantasies for arguments.

Notice our last conversation:

I said in a spirit of sheer discussion, and with your interest in mind, that the decisions you were making were all gambling (i.e. taking a chance on Tallulah’s returning to the part; taking a chance on the public’s finding any interest in the play with Hopkins and Nagel in it) and you answered that you’d never made a wrong move yet.96

What kind of answer is that?

In the first place, it’s untrue; a manager whose 3 stars abandon a successful play the minute their contracts run out has bungled his managerial function in a way that would make Charles Frohman, Belasco, Sam Harris and Max Gordon97 laugh with contempt.

In the second place, it’s a wishful fantasy. It’s a little venture at prophecy. Business isn’t conducted by boasts and predictions; neither is war.

In the third place, it shows how completely emotional your whole relation to the production has become. Your answer shows that for you the whole production is staked on your self-consciousness.

The moment that happened your ears became closed to discussion; you dried up any approach of friendship that I could make toward you; and you became a tiresome bore.

Through emotional self-justification you began raving about how Conrad Nagel and Miriam Hopkins would give better performances than Freddie and Tallulah; and how Tallulah’s record in THE LITTLE FOXES98 proved that there’d be no audiences for her in this play,—you knew in your gizzard that that was all eye-wash, but you were deaf and dumb and thought that Harold99 and I were infants.

You broke the approach of friendship; you made discussion impossible; and you became a hysterical bore.

That’s what the practice of hate does. By design and by your own confession, you employed hatred as an administrative method from the beginning. It took; and the blood has rushed to your head ever since. Now you imagine that everyone hates you and you plunge from one distorted position to another.

For God’s sake, clear your head.

You have a large theatrical property.

Manage it judiciously, and from a distance.

It’s a play basically requiring high standards; maintain them.

Don’t listen to Shubert Alley wise-guy advice; they don’t know anything about this kind of property.

See that it satisfies the highest type of audience in every town,—then the hoi-polloi will follow. But if you direct it to the hoi-polloi, they won’t like it and you’ll have lost any solid following.

You have my friendship waiting for you when you’ve emerged from your illness, and show yourself again an able business man; a cool clear administrator; and a worker in the arts who is unshakeably set on only being connected with the highest standards procurable.

When you can assure me of that, I’m

Your old friend,

Thornton

Censored

T.N. Wilder

HQ NAAF A-5

APO 650

c/o Postmaster NY NY

Sept 15 1943

Dear Mom:

Lovely long letter from you.

I am delighted to learn from you that I am the one of your children who is now most a subject for your concern; for I am not likely to cause you any beyond what your imagination can invent. The city I was in for a month and a half had many mosquitoes, but the citizens were proud to say that none of them had been carriers for ten years. This is hard to understand, because the city was very dirty, as they all are here. At present I am about 10 miles from another famous city; here the mosquitos are carriers and we sleep under nets. A number of my colleagues have had short fits of malaria, dysintery, etc. I suffered with the latter for one day. I confess I do not take the atropin table<t>s urged on us by the Medical Corps and placed in every mess. I don’t like drugs of any kind, unless you call whisky a drug and I get none of that here. Africa is the continent of insects. I think using Lifebuoy soap has kept me fairly unmolested.

A-5 has moved into a wealthy Mohammedan’s villa. Seven rooms about a large central court. Hideous “European” murals. A Squadron Leader; (i.e Major) a Flight Lieutenant (Captain) and I share a room, and are a congenial and gratifying example of “combined staff” harmony. The Mediterranean is a heavenly blue. The place-names of the region are famous in warfare, ancient and modern.

It’s true that I was in one raid which I shall remember as the most magnificent display of pyrotechnics that a small boy could imagine. 40 planes of the enemy did little damage and were driven off with losses. It was at 4:00 a.m. and you know how I like early rising.

I loved your going to Hartford to shop with Mrs Burton, and would like to see what you both bought. And I loved Isabel’s account of your gira100 to Boston, the Pioneer, the visit backstage, etc. And I liked best your determined resolve to live well past 90. Take care of yourself, especially on those back stairs. Try not to be a concern to me and I’ll take care not to be one to you.

Lots of Love,

Thornt.

Mediterranean Air Command APO 512

c/o Postmaster, NY, NY.

Dec. 20(?) <1943>

Dear Ones:

A new address

I don’t dare think how long it may have been since I last wrote.

We moved because we have a big piece of new work to do, and we had to begin the work before and during the work<move?>. We’re back in the second city in which I was stationed before. I love it when the work is concrete.

This afternoon when we asked our boss, the Group Captain, whether there was to be a “office conference on progress” he stopped and thought a minute and said, “No,—my advice to all of you is to go out and take a long walk.” Oh, boy,—I walked home and took a nap which was mighty welcome.

Now, dears, I gotta tell you an awful thing,—I am now established in a billet of delicious comfort!! It weighs on me. Two other officers and I have a 5 room apartment on the main street of the city (elevator and everything); we have a bonne à tout faire,101—une “perle”,102 who adores us. We draw comestibles from the quartermaster and she cooks our breakfasts and dinners. The minute we take off a piece of clothes she whisks it away and washes and irons it, and refuses to think of keeping a record and being paid for it. What’s more, her soups are delicious, her coquilles (from G.I. salmon with bechamel sauce), everything.

She is slightly touched with what G. Stein calls “cook-stove craziness”; but I like her fine and she’s recounted the story of her 56 years to me with details which would have startled the late Delia Porter.103

I get up at quarter to seven from between real sheets. I bathe cold, but I could bathe hot, if I dared manage the alarming looking geyser which has a pilot-light on, like a perpetual votive flame. I take bus, tram or hitchhike a considerable distance to the hut (“Nissen hut”) in which my desk is. Lunch at “Senior Officers’ Mess”. Start home about 7. Loud welcomes from Françoise. Dinner and early to bed to read a little Balzac before turning out the light. Such are the rigours of war.

Another thing has arrested us all from writing. No one can settle for us what our address is. We have risen one echelon higher, yes, ma’am. I am now the head of Mediterranean Air Command Air Plans III. All MAC is one APO number. Should we or not, include our section? Is it a breach of security? Yet if we omit it, would correspondence ever reach us?

Darlings, your packages are piled up in one corner of my armoire. Christmas day will be like any other day probably; but one of my housemates has ordered a turkey from a farmer (an American!) 15 miles from this city, and that we’ll have on the Eve and I’ll open my packages by myself in my luxurious bed after dinner.

Dec. 21

Again interrupted.

Work increases. I love it, and enjoy the approval of my bosses. Someday I shall a tale unfold.

This letter’ll never get off, if I don’t give it up to the Sgt. now.

Look at the date.

We don’t even think Xmas yet.

But

tons of love

Thornton

T.N. Wilder, Major AC

HQ MAAF

APO 650

U.S. Army

July 28. 1944

Dear Mrs Metcalfe:

Indeed I understand very well the assumption behind your letter that Charlotte judging by her letters may be soon permitted to return to normal living.105 We have it often, too, after a visit to her when her conversation for the most part gives every indication of being restored to herself. I have not seen her since I came overseas, more than a year ago. For a time she had seemed to benefit greatly from the shock treatments and several of the nurses said that they had never seen such improvement in her type of illness.

Unfortunately, however, the lucid interval and the balanced letter are only a part of the story. For us the distressing part is the sudden bottom falling out of a conversation and the disappointment to our hopes: the sudden insistance that she has only been ill a year; the announcement that there are many people going around in the world saying that they are Evelyn Scott or Thornton Wilder, but that they aren’t and that we must protect ourselves against them. From the doctors’ point of view a still more conclusive reason that she is not well enough for removal is the fact <that> she towards the doctors—all of whom have been unfailingly tactful and discreet—she maintains an implacable silence & pretends not to see nor hear them.

Fortunately for my own reassurance that no injustice is being done Charlotte’s opportunity for the best surroundings conducive to her recovery is the fact that Dr Tom Rennie, the head of the Psychiatric Section of the NY Hospital and one of the most distinguished doctors for mental illness in the country is a friend of mine; has interested himself in Charlotte’s case and is able to read the reports which we are not allowed to see. He assures me that there is still a measure of hope that she may rejoin the outside world and that he will continue to follow her case and let us know when he thinks that she has sufficiently recovered to justify a change of background.

Sincerely yours

Thornton Wilder

HQ MAAF APO 650 Oct 17, 1944

Dearest Twain: Suddenly I’m aware again that quite a time must have elapsed since I last not only vowed each morning to get a letter off before the day was over, but did it. My days are more and more cluttered with other duties than my military. The American service personnel who are interested in putting on plays have urged me to let them do Our Town, and I can’t offer any very good reasons not to, so a group of soldiers with little theatre and professional experience and some WACs are already rehearsing. In addition, I was pushed into being Acting Chairman—I at least insisted it was only “acting”—of the committee supervising all productions at the Hq., and now there’s a perfect fever of theatre going on.—there were highly successful runs of “Outward Bound” “Rope” “French without Tears” and <“>Pirates of Penzance” and now four companies are rehearsing Arsenic and Old Lace, Blithe Spirit, Tons of Money and Our Town. All this requires a lot of coordination and committee and club meetings, and is accompanied I’m sorry to say with a lot of underground politics and some very bitter feuds. I’m getting out of the chairmanship as soon as I can, and will restrict myself solely to overseeing the Our Town. ¶ The Wing Commander is back from his wedding journey106 and the eternal teasing of him by the entire staff will soon die down, speriamo.

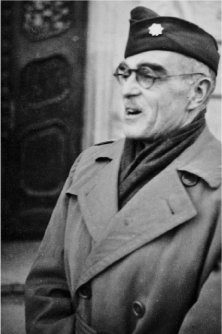

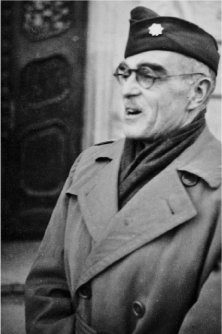

TNW as a lieutenant colonel in the Army Air Force.

TNW as a lieutenant colonel in the Army Air Force. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The capitols of enemy held Europe, are falling<.> Riga and Athens these last few days; two more any day now.

We gave a goodbye party to another of our staff who got an appointment at the Pentagon. I was told the same could be had for me for the asking but I replied that I didn’t want to go there or home, until this mighty action had seen its ending.

It’s getting colder, dearies. I don’t wish to harrow my mama, but it certainly is idiotic the way that during the day I forget to call up the billetting officer and ask for another blanket. I only think of it nights when it’s too late!! So I put rolls of Sunday NY newspapers under my lower blankets—newspapers are very good insulation—and my heavy raincoat over my feet and over the two other blankets—can you bear it, mother?—and make out very well. Today, and no later, I shall call up and arrange for everything. My colleagues who were here last winter say that seven blankets is par.

Rê Xmas presents. Well, dears, edibles are highly welcome. Due to my not going to mess at noon and merely nibbling sweets. From the PX we can draw unlimited fruit juice so that prevents my picnic lunches from being downright deleterious. What is most deleterious, however, is sitting down to a full dinner at noon. As for the rest, any practical clothing from underwear to sox are also welcome. Heigh-ho—what I want most is to give you some big hugs and lie on the hearth rug and listen to the radio describing the reconstruction activity after the war.

lots of love and you’ll hear from me oftener.

Thine Thorny

P.S. I’m still in top health, girls, explain it.

HQ MAAF APO 650 c/o P/M NY NY Nov. 10, 1944

Dear Ones.

Such fascinating packages arriving from you every day. The smaller ones I shall dip into as comestible in order to augment my picnic lunches,—ie that retirement to my tent, disdaining the plethora of the mess, and opening a can of fruit juice, etc, etc, reading a few pages of Freeman on Lees Lieutenants or Croce on old Naples,107 occasionally catching a cat’s nap, etc.

Our Town rehearsals go on pretty well. I’ve rec’d very high approval for the transfer from an air combat unit of a sergeant who was asst stage manager at the Los Angeles production—so I won’t have to give so much time to it. The “Stage Manager” does pretty well, but he’s atrocious in the clergyman’s speech at the wedding. How that must have been misread in the many small-town productions. It’s not a small-town comment on the ceremony!

I loved your letter on the garden. I love all your letters and don’t deserve them. Its downright abysmal how few I write: between rehearsals on alternate nights; Hq. Theatre Club committees (very stormy) on other nights; a new military committee I’m on and which requires writing up reports on other nights, I get very little time. Since with old fashioned scrupulousness I refuse to using<use> the working day for such things. This minute it is 0825 and my colleagues have not yet appeared.

Nice letters from Eliza and Rebeckah Higginson.108 Helen Hawey<?>109 sends me impetuous greetings from time to time and even got a book to me without my having requested it (Little Coquette—tepid Tilleul)110

Day follows days with an featureless uniformity, a sort of winter quarters monotony. Some pleasant new officers have joined our section to replace those who sweated to get themselves into the Pentagon. An order suddenly closes all civilian restaurants in Italy to service personnel, so the little Italian grape arbor trattoria to which I took many an acquaintance is now out of bounds. I paid a last visit to Signora Napolitano (the family name) and to little Catarina (aged 10—but what a capable little manageress since she speaks Inglis) with many protestations of undying affection.

The wedding which I practically staged is a great success in many ways. Already Mrs L. (Flight-Officer WAAF) knows she is to become a mother, so by regulations she is hustled back to England by the first boat, discharged from the service (tho’ honorably) and generally encouraged to increase the population of the United Kingdom. I have been a very close party to all this, even my rich store of learning in gynecology being put to service, so there’ll be lots of tears to shed when Eileen leaves her husband and “loco parentis”.

Oh angel-mama, the letter I wrote to make you happy, succeeded only in distressing you. I cannot repeat too often that I love my tent and my fixtures and my getting up and my lying down. It’s not only comfortable in itself, but I have a temper which finds things comfortable about me, what a fortunate young man, and how devoted to his mother and sister to whom he sends his love

Thorny

Feb 15 1945

Dear Eileen:

You can imagine with what absorbed interest I read your letter (and reading correctly, I hope, still further between the lines) and with what interest I listen to Roland as he thinks aloud about you, which he loves to do with such moving affection.

I try to imagine what the life is like there. I’m angry angry angry at the weather. There’s nothing harmful about outdoor cold as long as one is warmly dressed and if there is, at least occasionally, sunlight. Its long been noticed that very young children thrive on outdoor cold, if they’re warmly dressed. Their faces seem not only <to> bear the cold better than ours, but even rejoice in it. But, oh. I wish you had more sunlight.

I’ve been thinking over, as you asked me to, some occupation for your time and attention that can remove you at least for a few hours every day from the routine-domestic and the self-occupied reverie. (There’s nothing wrong in itself with long meditative hours about yourself and Roland and the child; its only that there comes the moment in such thoughts daily when they start repeating themselves and going around in circles; that is the moment when they turn into dejection, or worry, or self-pity, or conscious loneliness: and that moment one must rise firmly above and occupy oneself at something else.) <appeared perpendicularly in left margin> Rê all this I remember my dear Gertrude Stein once saying that ‘the business of life is to create a solitude that is not a loneliness’’. And that’s where the fine arts and the intellect and each person’s creativity comes in. My regards to MM.111

What I am going to suggest is this that you set aside a number of hours every week to go to the University or municipal libraries (if you find yourself getting interested this may turn into several hours a day) to read and study systematically: the Psychology of Children. I have known a number of young mothers whose friends or doctors placed such volumes in their hands, but they read them only desultorily. They were too absorbed in maternity itself; they told themselves that the “maternal instinct will enable them to supervise the early years of their children, etc.” But it is a science, and one which has made extraordinary advances in modern years. Moreover, it is a profession requiring training and skill. I hope (and there is every reason to believe) that you and Roland will live a long long happy life together; but maturity teaches us to look in the face all the accidents which might arrive in the future. It is only one advantage of the project I suggest that if under certain contingencies you could demonstrate that you were well-read in the psychology of children you would find yourself eagerly sought after. one thing we’re sure of in the world of the future is that the Governments are going to interest themselves in the physical and mental well-being of children.

The one drawback against the above suggestion is that the latest studies about it are full of material which laymen would call: “unwholesome.” The world’s authority is Dr Anna Freud, whom I know, the daughter of the great Doctor. Don’t begin, then, with the psychoanalytic books on the subject; save them until the later stages. The really important thing now is that your mind is principally filled with confidence, gratitude, and proud tenderness. Whatever vexations the daily life and the weather and separation and the stringencies of wartime living may bring, do, do combat as far as possible any mental inroads on your sovereign mind: there we can all be rich, serene, and (blessèd word) independent. Perhaps one way to combat just such vexations is to tell Roland about them (and me, if you had time; or me through Roland). He won’t misunderstand as long as you can assure him that you’re also proud and happy to be Mrs Le Grand and mother.112 God bless you,

Thornton

HEADQUARTERS MEDITERRANEAN ALLIED AIR FORCES APO 650, U.S. Army

February 18, 1945

Laurence Olivier, Esq.

New Theatre,

London, England.

Dear Mr. Olivier:

It has been a great satisfaction to me to know that you and Miss Leigh are interested in putting on “The Skin of Our Teeth”. Through my sister Isabel’s letters I have followed the various negotiations including the preposterous deal Michael Myerberg got into with Miss Mannering. I hope that has been straightened out and that your title to it is completely clear.114 Isabel writes that your return to the service is due and that you will have time to direct but not to appear in the play. My admiration for your work is such that I am equally satisfied with this arrangement and hope that it can be put into effect.

I was delighted to hear that your idea was to caste the play with “unknowns” and to so direct them that the result would be a sort of half-way approach to an American manner. Such a procedure might improve on the one drawback I felt behind the New York presentation: the performances of the principals were excellent throughout, but they projected them with the studied precision one would look for in “The Wild Duck”. My idea is that the play could give practically the sense of improvisation, a free cartoon, “The History of the Human Race in Comic Strip”. At one time I hoped there would be a performance by negroes whose spirit of play, spontaneous emotions, musical voices and uncomplicated idealism (Rodin’s Adam!) would have captured this quality so well.

All negotiations about my plays have been handled from New York and New Haven to such an extent that I do not even know who is acting as my agent in London. Could I ask you therefore to see that the following appointment is offered to Lady Colefax, in the earnest hope that she will feel able to accept it, and that the appointment is understood and negotiated through that agent?

It is my hope that Lady Colefax will serve as the Author’s Representative and working very closely with the producer, will have full authority to answer for the author and represent him in the following ways:

The advisability of cutting certain lines and business or adding others necessary to the better understanding and effectiveness of the play.

Consultant on scenery and costumes. It is recommended that in deliberations on casting her opinion should carry considerable weight.

It is hoped that from time to time during rehearsals and performances she will circulate among the company and be accessible to the performers. It has been my experience that the author or his representative can adjust slight inconveniences and personal frictions in such a way as to aid the morale of the production out of all proportion to the apparent importance of such service.

For these services the Author’s Representative will receive 10% of the author’s royalities computed prior to the deduction of taxes.115

I hope the production will give you pleasure during its preparation and gratification with the results.116 Kindly convey my regard to Miss Leigh also.

Sincerely yours

50 Deepwood Drive Hamden

14 Connecticut (Only lookit: AAF Redistribution Station No #2 1020 at<?> AAFBU

Squadron H, Flight 455-C Hotel Caribbean, Miami Beach, Fla)

May 20. 1945

Dear Harry:

Now hold your horses. This is what happens when you return for reassignment.

Within three or four hours of arriving at the post of debarkation (hold your hats, now) you’re en route to your home on a 21-day visit. (I waived that in order to expedite matters and God what a fool I was.) Then you report to a Redistribution Station.

You bring your wife, if you choose. You live in a luxury hotel at the seashore—Santa Monica, Calif., or Atlantic City, or here. For nine days you have about two appointments a day. Physical exam, or Classification test, or orientation lecture. (Are you following me?) This applies to Enlisted Men or Officers, because they’re all in this very hotel, wives, too; the only protection against reciprocal contagion being that we’re on different floors.

Then you have to wait, some a few days, some months for their orders.

I’m in such a mess of red tape as has never been seen. Some Authorities say it’ll be two months before I even get to the Separation Centre. Archie Macleish phoned down yesterday, saying he’d effected my separation from the War Dept, but the separation within the Air Force is a thing that’ll pretty much have to take its own course. Anyway, tomorrow noon I start being on Inactive Status, which is Step One. With that I can go home and do my waiting, but I travel at my own expense. Query: crazy to learn tomorrow whether Inactive Status gives me gas and shoe ration coupons. All the shoes I got are those I stand in, and my family is certainly going to look for gas coupons after the first hug has abated.

May 22. 1945—Continued over.

Okay. I go North tomorrow on thirty days’ leave while the Headquarters meditate on my forward application for separation from the service, with the State Dept’s appointment submitted as In closure #1.

Well, well, well, won’t it be funny to see the family again and the New Haven Green? I’ve been here over two weeks, but I don’t feel I’ve appraised the United States yet. This town is as bad as Los Angeles and I hope no one ever takes it as an index of what the country has to offer. It’s a honkytonk de luxe and always has been.

I still have that feeling of being a piker through my running off and leaving you and Bernie and Morrill118 on that … ship. I hope all goes well with you, that you get interesting jobs until its all over, and that you get the advancement that lies just ahead of you. When I spoke of that to Col. Burwell, he acted surprised to hear that there was a Tech. sergeantship on the T.O. I hope he’s keeping it in mind.

When I phoned my family they told me that a cable from Laurence Oliver and Vivien Leigh had just arrived congratulating me on a big success in London with the play. I hope it’s true, as much for their sake as mine, because that play will always have brickbats and indignant customers, whatever the critical reception is.

I’ve already written the Wing Commander; give my regard to Col. Alston and tell him I’ll write him soon. And do me one favor: I was prevented on that last day from running around to find Wilcox. Do look him up and tell him he has my lasting esteem and that I shall always be glad to hear from him. The opportunity to do him a favor of any kind would always tickle me. The same applies to you ten-fold, Harry and don’t forget it, Indianapolis.

Yours in war and peace

Thornton Wilder

Back in a week or two at: 50 Deepwood Drive

Hamden 14, Connecticut

(AAFRS No. 2, Miami Beach, Florida)

August 20 1945

Dearest Sibyl:

Two letters from you, though written on the 2nd and the 11th, arrived this afternoon. ’Ate ’em up.

I’ll take up some of the agenda seriatim and then I’ll see what I’ve stored up to report.

RETREAT: We’ve just been released unlimited gasoline (but tires are hard to get). I’m thinking now of going, not to Colorado, but to Acapulco, Mexico. Driving there viâ Chicago (i.e. the Hutchi, Amos and my wunderkind nephew); down the Mississippi to New Orleans (Sibyl, what meals—): then to Texas, and down the great “new” road to Mexico City. Down SW past Cuernavaca (where I once went to work, but the work wouldn’t come), past Taxco with its famous little cathedral to Acapulco on the sea. It’s become very swank, unfortunately: Hollywood flies down there week-ends to marry and millionaires to fish for black marlins (having caught one, you sometimes have to “play it” for five hours). But there are many hotels strung along the black cliffs, a Mexican Town of 20,000, and I hope little subsidiary plages up and down the coast.

THE NEW PLAYS: (Thanks for asking.) For Alcestis I want Elizabeth Bergner. Who else? In the first act, an exaltée faintly “goose”-like young girl; in the second, the greatest golden young matron of all tradition; and in the last the agéd slave, water-bearer in her own palace, with scenes of tragic power and mystical elevation. Who else? And all to be played against that crazy atmosphere of the numenous that is possibly hoax and the charlatanism that may be the divine. And the preposterous-comic continually married to the shudder of Terror. When Heracles goes down to wrestle with the Guardian of the Dead for Alcestis, it’s no joke and yet the great generous demigod is terrified and very drunk. I sit here writing one big scene a day (awaiting orders in this luxury hotel, my window over the surf and the greenest ocean,—with next to nothing on, for its very hot and humid); the play is a chain of big scènes à faire.119 But oh, Sibyl, it’s very hard and every-other day it seems clear to me that it can’t be done. The whole play must be subtended by one idea, which is not an idea but a question (and the same question as the Bridge of San Luis Rey!); and each of these scenes must be balanced just so and not give a wrong impression about that idea. And no two minutes of it must be too romantic, and none too pedestrian, and none too comic, and none too grandiose. And the great temptation is “to just write it any old way” and trust that “no one will notice” anything but its dazzling theatrics. oh, dear.

“The Hell of Vizier Kâbaar”, that will be more difficult still, but in a different way. That will require the good old-fashioned plotcarpentry that I’ve never done; the joiner’s art that must be then rendered invisible, as though it were perfectly easy (like the last movement of the Jupiter, God save the mark.) The danger of the Alcestiad is that the effectiveness may be greater than the content (to which Jed replied, quoting an old Jewish exclamation: “May you have greater troubles!” but what greater trouble could an artist have?) The Hell of. …. can’t run into that danger. It’s content is not a hesitant though despairing question.120

THE OLIVIERS: Oh, dear. I’m afraid that I may have said something in one of my letters that hurt their feelings. I’ve never met them; but even to strangers in whom I have such confidence as I have in them, I run on so, I babble, as though I’d known them twenty years. I assume that they know me, that idiotic bundle of conceit and modesty, of dogmatic assertion and exasperating non-commital; of excessive intimacy and intermittent withdrawal. At a pinch I can write a formal letter. But I can’t write an almost-formal letter, and so I’m always getting the tone wrong. Anyway, I honor and admire them boundlessly. I hope they will dismiss me as crazy, rather than think me rude.

CHURCHILL: Do you still have the feeling that the election could be described as showing ingratitude to the Prime Minister? Or that, the first week past, he would interpret it so? Never did he have a better press than the valedictory one, over here. But I’m like to get beyond my depths in your politics or ours.121

KIERKEGAARD: Strange things happen when I start raving about S.K. I blew a blast of him, over some cocktails, at Cheryl Crawford. She couldn’t wait until Brentano’s opened next morning and marched off with Either/Or (a vast mixed dish) and The Theory of Dread (the first half of it, uncharacteristic metaphysics). I recommend starting with two little volumes Fear and Trembling and Philosophical Scraps122 (or Remnants as sometimes translated.) Anyone<Anyhow>, if you are indeed tempted, and thus have given me permission, I shall send you copies, perhaps my copies with their vociferous marginalia, if I can get them back from the latest borrowers. The best sign that I like a book is that it has left my house. Yes, beauty, art, and memory are enough. As bargainers say: I’ll settle for them. But the point of S.K. is that he begs us not to settle for them too soon; the prizes beyond those things he makes more enviable exactly by making them more difficult and more painful (just where protestantism has been saying they are easy and consoling.)

I must go or I’ll miss mess. All my colleagues are ex-PW from Germany. Stories!

Sibyl dear, (as brides say: “I want you to be among the first to know”) I have been awarded the Order of the British Empire. That with my Legion of Merit brings my three years of the war to a happy close. There are few satisfactions greater than knowing you have the approval of your superiors in a job which involved their responsibility as well as your own. When I heard of this, I thought of my favorite Britisher in the world: “Sibyl will be pleased,<”> I said; <“>Sibyl, who’s done so much for me, who’s worked over me.<”> There’s a part of my heart that is forever England and over it is a little band of pink and grey ribbon.

(Mess call.)

Lots of love

Thornton

Jan 2. 1946

Dear Byron:

Fine.

Fine.

Delighted that you both met the Chief.124 Though I’m concerned about his being x-ray’d.

x

Emmet Rogers.125

A nice enough fellow—but, believe me, acting is not a profession for adults. It is mostly entered into by the kind of person who has no intention of being an adult, and once in it the very exercise of the profession breaks down most of the traits that make for being-the-master-of-one self.

Think of how extra bad it is for a man:

You must say words which are not your own.

You must say words which are not your own.

You must assume emotions—which are not spontaneously prompted.

You must assume emotions—which are not spontaneously prompted.

You must be aware, down to the finest shade, of what you look like.

You must be aware, down to the finest shade, of what you look like.

You live to please, impress, or gratify strangers.

You live to please, impress, or gratify strangers.

I’ve known many actors and Larry Olivier is the only one who has not been trivialized and soften<ed> by those requirements.

x

Your paragraph on the U.S. and your idea of a livelihood is written as though you expected me to disagree with it word by word.

x

No, no. Since these things are real to you it’s important you do them  live outside the U.S.

live outside the U.S.  teach English to support yourself.

teach English to support yourself.  deliberately set your marks for a very limited income.

deliberately set your marks for a very limited income.

All I say is do not concretely or mentally pour your thought into that as a life-long picture. Because:

one falls into the danger of confusing one’s impatience with one’s fellow-countrymen and one’s impatience with human beings. The trouble with America is that its full of Americans, that’s certainly true, but it’s not a more pleasing thought when one reflects that (in the mass) England’s full of the English; and so on. I have known many expatriots (this does not include refugees) and I swear to you that I’ve only known one who was not devitalized by it, and that was Gertrude Stein. Aldous Huxley is palpably thinned out by it; the American “artists” in Rome; the worldlings and the couples with jobs in Paris (“Oh, we adore Paris; we wouldn’t think of going back to Baltimore!!<”>) whom I knew; such people at Capri; at Taxco; at Oxford. Without realizing it one has been made American by living here the first 15 years of one’s life; to slip away from coping with it is to injure oneself.

one falls into the danger of confusing one’s impatience with one’s fellow-countrymen and one’s impatience with human beings. The trouble with America is that its full of Americans, that’s certainly true, but it’s not a more pleasing thought when one reflects that (in the mass) England’s full of the English; and so on. I have known many expatriots (this does not include refugees) and I swear to you that I’ve only known one who was not devitalized by it, and that was Gertrude Stein. Aldous Huxley is palpably thinned out by it; the American “artists” in Rome; the worldlings and the couples with jobs in Paris (“Oh, we adore Paris; we wouldn’t think of going back to Baltimore!!<”>) whom I knew; such people at Capri; at Taxco; at Oxford. Without realizing it one has been made American by living here the first 15 years of one’s life; to slip away from coping with it is to injure oneself.

All right—one teaches a subject 5 or 8 hours a day in order to make the livelihood by which one exists. But isn’t that a second prize? Isn’t the first prize to make one’s livelihood with joy, as well as one’s leisure? Five hours to drudgery in order to have 8 in which one “lives”—but the happiest lives are those in which there is no division between “working” and “enjoying”.

All right—one teaches a subject 5 or 8 hours a day in order to make the livelihood by which one exists. But isn’t that a second prize? Isn’t the first prize to make one’s livelihood with joy, as well as one’s leisure? Five hours to drudgery in order to have 8 in which one “lives”—but the happiest lives are those in which there is no division between “working” and “enjoying”.

Money. Through the Grace of God you happen to have the finest wife in the world.126 Never forget, however, that straightened means bear down on the wife twenty times harder than on the husband. However, clever she is in running up meals “by magic”, in cleaning and dusting as tho’ it were “fun”—they pay. They pay not only by work, but by preoccupation; it literally and inevitably takes their mind. Women live and love to serve us; it’s part of our business to prevent them doing it beyond a certain point. ¶ Money has three dignified uses (and they do not include owning beautiful things or providing recreation)

Money. Through the Grace of God you happen to have the finest wife in the world.126 Never forget, however, that straightened means bear down on the wife twenty times harder than on the husband. However, clever she is in running up meals “by magic”, in cleaning and dusting as tho’ it were “fun”—they pay. They pay not only by work, but by preoccupation; it literally and inevitably takes their mind. Women live and love to serve us; it’s part of our business to prevent them doing it beyond a certain point. ¶ Money has three dignified uses (and they do not include owning beautiful things or providing recreation)

Saving time

Reducing drudgery

Furthering the health and education of children. Well—never did I feel so like an uncle, nor so devoted to my nepotes

Ever

Thornt.

March 9. 1946

Dear Friends:

It is not only work which has kept me silent and interrupted my correspondence with even my best friends. It is a sort of post-war malaise which I won’t go into further lest I give the impression of self-pity or misanthropy or melancholia. It’s none of those things. Call it out-of-jointness, and forgive me. I think I’ve recovered now. Whatever it was it didn’t overcloud the fact that I love the Le Grands, old and new, and always shall.

As I think I told you, red tape delayed my demobilization from May to September. The papers must have been lost in some officers in/out baskets. I didn’t greatly mind; some of the time I was allowed to wait at home; the rest I spent in the hotels of Miami Beach which had been turned into “redistribution” quarters; but waiting-time is not conducive to work, and perhaps what I wanted was a good excuse not to settle down to work. Finally out I took a trip to Florida and Georgia and did begin work, but its been slow, reacquiring habits of concentration and perserverance.

In the meantime I have been “inhabited” by two compelling enthusiasms. An accident turned my attention to the problems connected with the chronology of the (circa) 500 extant plays of Lope de Vega. I hurled myself into scholarship, spending 10 hours a day in the University Library and making trips to libraries 100 miles away in search of further sources, and I discovered new data. I think that this passion was a useful therapy: pure research has nothing to do with human beings; it has little even to do with taste or aesthetic judgments. Finally I saw that the ground I was working in was a Life-work; wider and wider vistas opened. It was Escape, and finally I willed myself to quit it. Roland, if you want to prepare a thesis in the Spanish golden age, I’ll send you all my notes. There’s a beautiful thesis there, in a territory where all the Spanish and international scholars were in error. Ready for the asking.

Lately, I have been absorbed by Existential philosophy and its literary diffusion, especially in France. Jean-Paul Sartre has been here, and I have seen him many times. Your London reviews are full of it. It is fascinating, not as nihilistic as it appears to be on the surface, and it is magnificent evidence that France remains a great power, whatever its political and economic situation.

The Alcestiad is almost finished. It waits on one last clarification which I must clear up in my own head, philosophically, before I can project it into the web and woof of the lives of my characters. I have also begun that novel-in-letters about Julius caesar and the scandal of the profanation of the mysteries of the Bona Dea.127 I should say that the two works are racing in competition except that such slow work could scarcely be called a race.

Now that I am out of my acedia128 sufficiently to write letters, I shall write Pank, and Vera and Mike Morgan and the Trolleys, but I’ve begun with you, dear Kinder. The silver mug is all engraved with Julian’s name, but we were told that it can’t be sent. My sister Isabel is going to London with the newly-formed “Our Town” co., and if she goes by boat she can bring it.129 That may be very soon. I may follow in the Autumn,—oh, what good talks. Oh, what dandling of babies. Oh, what insidious instruction in an American accent to say “Uncle Thornton!” Heartfelt blessings on you all—

devotedly

Thornton

<P.M. March 30, 1946>

Kinder, Kinder, dear Kinder:

Excuse me if I sound smug, but I’m in a beautiful place under a beautiful sun and I haven’t a trouble in the world except that I’m pennilous, tubercular, and I’m not sure whether what I’m writing is worth a bean. Apart from that I haven’t a trouble in the world and am inanely happy.

Now let’s hear about you.

Kinder, do you read plays? Jean-Paul Sartre has given me the American disposition of a play he’s written that would freeze your gullets.131 Will any American manager produce it? Five French Maquis are variously tortured and raped by some Petain militiamen. But it’s not about the Resistance movement; it’s about the dignity of man and the freedom of the will. There’s not a cliché in it; its as bare as a bone in New Mexico; five characters wear handcuffs through the entire play; every agony in it must have been experienced in Europe a thousand time<s> and yet no American manager would venture to present it and we’re not grown-up enough for it and we’re not worthy of the U.N.O.132 and so let’s think of other things.

When are you two going to get a rest? Now, really; life’s short enough as it is. I’ll bet you Garson hasn’t had a 15-hour sleep for four years,—at least not without anxieties marching through his dreams like Hessians. I’ll begin to think that you two are bitten by the hornets of Ambition or the wasps of Competition. Swear to me on the Prayer-book and Talmud that you aren’t; that you’re sane, that your love for one another and the love that we extend to you is/are calmatives enough. You are successes, you are, because you’re loveable intelligent wonderchildren, but I’m beginning to think that there’s a slight admixture of Mexican jumping bean in you too. I wish to address the one nonchalant philosopher in the family and send my love to Jones.133

I wouldn’t scold the Kanins, if I didn’t feel lots of love

Thornton

May 31 <1946>

Dear Amy:

Can’t believe it. Isabel’s was over twice that. Glad to see that it’s deference to the Cloth.134

No, never heard of E. Rosenstock-Huessy.135 Glad to read anything you recommend and will return scrupulously.

Had some hours with A Camus. Lord be praised, I didn’t like him as much as Sartre or I’d have committed my time away in translations, services, etc. But I respect him and Le Mythe de Sisyphe is fine romantic writing, though he’d hate to hear it called that.

Isabel heard Dylan Thomas read some of his poems in London (she sat two yards from the Queen!), fine self-forgetting projection she says. He dresses “non-gentleman”. The distrust and unkindness of Englishman to Englishman along those hair-fine social categories has to be seen within the military framework to be believed; in what century did this profound evil enter English life? The infiltrations of vulgarians into the Serenissimi136 circles during the Industrial Revolution? That is just what Proust describes in his world, but there it didn’t result in the fear, nay panic, in an Englishman’s heart lest he be addressed cordially by some one! So of course Dylan Thomas wears colored wool shirts. How wonderful that the Scots lack any shade of it and move in and out. English life, not imitated and not catalytic, but unaffected.

The Achilles’ heel of the French is property and avarice (not luxuria137); of the British “Racha, thou fool”;138 of the Americans, self-righteousness—and here I am displaying it.

Our girls here are fine.

Our house is honored this week-end by two Golden Guests, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. Larry, the greatest English actor in 200 years, says he is using the drive down here to study Lear which he brings to London in the Fall!139

Love to you and your Loved-ones

Thorny.

Last days at Nantucket.

As from: 50 Deepwood Drive Hamden 14 Conn.

July 23. 1946

Dear Ones:

At the end all her dear traits became clear to us again but in a new light: her self-effacement in loving and serving; her Scots independence and desire to endure whatever she had to endure, alone; her distress at “putting people out”; and finally one we had never seen before,—the call for help.140

Isabel has been wonderful throughout.

I dread writing Vivien, Binkie,141 Sibyl, etc. that I am not going abroad, after all. I shall be at Deepwood Drive until Christmas, finishing the novel and sort-of re-establishing a home. Important for Isabel is the feeling that she is needed and useful somewhere; otherwise—you can see—she seems to hang in mid-air. ……

My hard work begins next Monday. I’m looking forward to those five weeks. Summer theatre’s so damned occupying. Carol Stone is to be our Sabina at Cohasset; the other productions will be full of old friends. Doro Merande, Coolidge, Tom Coley, etc.142

The novel’s full of glitter now that Cleopatra has arrived in Rome, but its also getting deeper, wider, and more preposterous,—yes, that’s the word for the burden of vast implications I’ve assigned myself.

We’ve been reading about the March’s possibly taking part in Miss Jones.143 I’m sure that under Garson’s hand they’d be fine; but I’ll have to hover about in the last row disguised. Florence was very incensed by a moderate letter I wrote her and I doubt that she’ll ever consent to speak to me.

Monty Clift writes me that Garson was a wonderful help to him in the tangles of Hollywood negotiation. I’m afraid that fellow’s going to get caught in delays, re-tests, refusals of scripts, and a whole season will go by without his having played anything or ending up as the Young Man rejected by Barbara Stanwyck’s daughter.

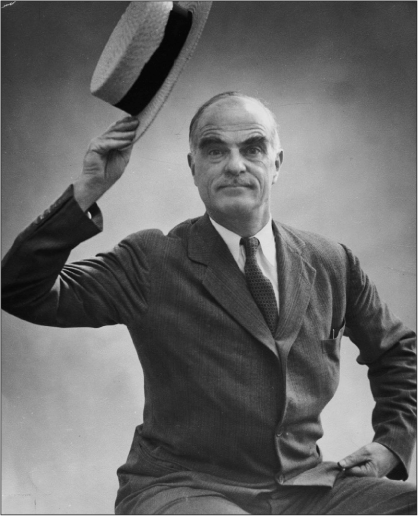

TNW as George Antrobus in The Skin of Our Teeth.

TNW as George Antrobus in The Skin of Our Teeth. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Garson, William Layton writes me that there is talk of his being asked to read for the part of the New Republic Editor in one of your companies.144 At his request and in dutiful memory of Woollcott who’s secretary he was, I hereby put in a word for him. He’s just come back from the London “Our Town”; was the Radio Operator in a year of “The Man who came to Dinner”; a Marine in the Pacific for years; a trained actor, with a steady unvarying authority that was a benefit to the whole London venture, and a fine fellow. To be reached through Joe Magee of the Wm Morris office.

Try and remain modest and unspoiled, dears, in spite of the fact that you’re the best, brightest, sturdiest, most gifted and most lovable urchins in the world.

your old

Thornton

October 8 1946

Dear Alice:

These last weeks, in whatever company I’ve been in, I’ve silenced the aimless talk that goes on in order to tell them about Gertrude, about the several Gertrudes, the Gertrude who with zest and vitality could make so much out of every moment of the daily life, the Gertrude who listened to each new person with such attention and could make out of her listening such rich reinforcing friendship, the Gertrude of intellectual combat who couldn’t let any nonsense or sentimentality or easy generalization go by unpunished, and finally the greatest Gertrude of all, the inspired giant-Gertrude who knew, and who discovered and who broke the milestones behind her.145

Oh, miserable me, I lost my mother this summer. I havent a right sense of time. I’ve lived as though I assumed that we’d have these infinitely treasurable people always with us. I never foresee their not being there. It may be that this makes my losses twice as cutting, but I think it has one consolation: while they were alive I had them really as a possession, I didn’t feel them as temporary. My Gertrude is always there, as she was there before I knew her, which is to say: always here.

My poignant self-reproach at not having written her is acute. It doesn’t help that I remember that she taught me how all those audience-activities—“articles”, letter-writing, and conversation itself are impure at the source,—but oh! that I had at least sent her signs and signals of my ever-deeper love and endebtedness.

At the time of her death, so soon after my mother’s, I was booked up with engagements acting in my plays in the summer theatres. I was unable in that stupifying work to write an adequate, a half-adequate article for one of the weekly reviews,—revolted though I was at the incomprehension of their papers about her. Again, this unmarked sense of time came into play—that someday when I had realized fully her loss and had penetrated still further into the greatness of her achievement I should write what I remembered and what I had come to grasp.

During the War I was not exposed to any particular danger or even tension; I have no right, compared to my friends in combat, to claim any long slow and difficult readjustment; but nevertheless that’s what I’ve been undergoing. I seem only now to be emerging from a long torpor and misanthropy and paralysis of the will. My outward health soon recovered—the disabilities that prevented my fulfilling the appointment to the Embassy in Paris—but the psychological effects have dragged on for a long time.146

I do not know whether this silence and “absence” led Gertrude to believe that the literary executorship of her work would better be transferred to another person.147 If she felt so, I would very well understand it. If, however, she wished me to assume it I am as eager as ever and I hope as efficient. I mention it because I have interested the editors of the Yale University Press in a possible publication of Four in America which seems to me one of her most significant as well as her most charming works. It is the one I dreamed of publishing myself “the next time I made some money.” My money-making capabilities have slowed down, along with the rest of me, and if this turns out to be a real offer of publication I think it should be accepted. In whose hands would you like to place the negotiations?148

I have not said anything, dearest Alice, about the loneliness you must be feeling. All I can say is: WASN’T IT WONDERFUL TO HAVE KNOWN AND LOVED HER? What glory! What fun! What goodness! What loveableness!

Everything one can say falls short of it. Someday before long I shall try to put all that down in words as carefully chosen as I can choose them—in the meantime she grows in my mind and heart and realization. Her greatness in the larger world has scarcely begun yet; long after you and I are dead she will be becoming clearer and clearer as the great thinker and the great soul of our time.

With much love, dear Alice,

much love

Thornton

January 7.

<19>47

Monday

Dear Sibyl:

That’s the chief thing I have to say so I write that big.149

So, dear, I put this Fall into living in Deepwood Drive, and refocusing the ménage after it’s loss. We coped with the community; we went to people’s houses and we had people in. All this became positively mountainous over the holidays, what with eggnogs and everybody’s relatives visiting from out of town. Such greetings over cocktails; such “now we have to hurry on to the Tuttles or the Donaldson’s, or the. ….”.

So that’s done. The house is repainted. Isabel is installed in a great wheel of social give-and-take that will occupy her for years. During my absence a friend of long standing is coming to live in the house.

My sense that any particular value of heart or head is transmitted in “conversation” has never been very strong. It was much sapped during the War. So I went through all this with mounting fretfulness. I even developed a technique of coping with it. Dreading the conversations of others. … on politics or literature or on our neighbors. …. I resolutely set about talking myself on what interested me. During those obligatory two hours after rising from table at a dinner party or even in the meleé of a cocktail party, I too often threw my partenaires150 into consternation by insisting on telling them about Lope de Vega, Freud’s theory of the physiological basis for avarice, Kierkegaard and the “leap”. This practice cannot be acquitted of egotism; but it was not at least complacent egotism, for I did not enjoy it. It was a modus vivendi.

At last I can go. On the 15th of January I start driving to Mexico. And oh the exhalation of Relief and the joys of holding my tongue.

The work on the novel stumbled. But just last week I rolled up my sleeves to do a page or two to keep it in hand, and it came fine. [A sample from the Notebooks that Cornelius Nepos kept for potential biographies he might write some day. He had had Cicero to dinner and lured him into talking about Caesar. Cicero’s fear, envy, and incomprehension comes out as wit. Very funny. This book ought to have every color, and I knew that it had developed without much being funny—now it’s got some very funny places and will have more, juxtaposed with much that is painful and much that is, I hope, beautiful.]

So, dear, I shall miss Henry Uxbridge151 and John Gielgud. In the light of Lady Anderson152 all your recommendees are so joyfully rewarding that I regret this much. But I shall be at San Miguel or at Manzaniko.

Look at this wildly self-centered letter. Well, I am spiritually ill from lack of solitude. I shall return healed and a Franciscan brother of the human community. Now that the Dioscuri (Larry and Vivien,—I like to think of happy married couples as twins) are resting I shall venture to write them a letter. Yours are of such fascination and vitality that we forget that you are surmounting pain

You will hear from me oftener when finally I am not in the situation of a bear frustrated of his hibernation.

Lots of love

Thornton

As from: 50 Deepwood Drive. Hamden 14. Connecticut

New Orleans, La. Feb. 23. 1947

Dear June; dear Leonard:

I throw myself on your forgiveness. I had a sheltered life during the War and have no right to talk of post-war maladjustment, but that uprooting in my middle age did have bad after effects on me. One of them was a relapse into melancholia, lethargy and unsociableness. The death of my mother and the consequent necessity of settling in New Haven (i.e. Hamden) all Fall in order to rebuild the home for my sister after it had lost its center, all added to this. What I needed was to work, and in order to work, solitude, so soon after the New Year I left home and came down here. Tomorrow I take a tramp ship to Yucatán, and that will be sufficiently “cut off” and solitary. So I ask your forgiveness; and plunge at once into answering your questions.

a. Common Sense says that you shouldn’t cross the water now,—and yet. …… On the one hand, you know our Actors Equity rule that a non-American citizen engaged for a role here must wait six months at the termination of that role before assuming another. [Occasional exceptions are made when a manager goes before Equity’s council and asserts that such-an-such a non-American actor is the only one he can find to fill a given part.] Moreover, jobs are hard to find. Your theatre structures were reduced by bombing; our<s> by the fact that movies buy up the houses and convert them into cinema halls. There’s an awful dearth of theatres and plays wander around the provinces waiting to enter New York when a theatre tenancy is vacated.

And yet! There’s always the chance that a manager about to put on a British play would snap you up. For instance, John Golden plans to put on J. B. Priestley’s The Inspector Calls.154 I imagine there must be several roles in it that you could do; but Golden would have been interviewing hosts of young actors, British or pseudo-British

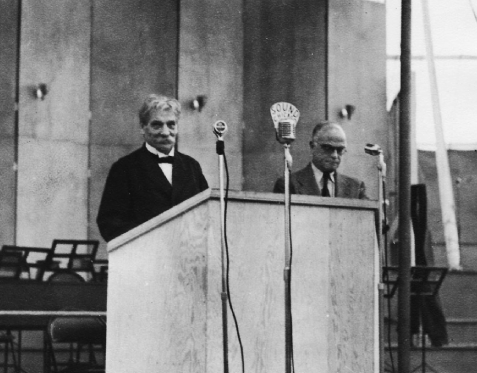

TNW with June and Leonard Trolley following their wedding in Rome on February 12, 1945.

TNW with June and Leonard Trolley following their wedding in Rome on February 12, 1945. Courtesy of Harry Traugott.

b. Movie work and radio would I think be out of the question until you had a number of engagements to point to as “experience”. Entrance to those fields is dark and mysterious. I know some awfully bad actors who flourish in them, and some excellent ones who can’t get a look in.

c. However, if the English stage is as blocked as our<s> is, and you may temporarily have to go into some other kind of job anyway, like the hotel business, or “gentleman front man” in a firm selling motor boats or motor cars, etc; maybe it would be right for you to cross over anyway—and do both your “earning a living” and your theatre career over here. The world’s going through an awful time; everywhere it’s hard; great migrations are taking place everywhere; one’s “nationality” is no longer as sacred a matter as it used to be. If you bright young children have to struggle and suffer somewhere, maybe you could do it here, where opportunity is perhaps a very few degrees less cruel. I don’t dare call what I’m saying advice. Perhaps June’s mother may have some thoughts in the same direction. We’re such old friends that I can say at once that I’d practically adopt you and would lend you the money to sustain yourself until you got on your feet. Such a transplantation should only be contemplated, however, if you sadly and inevitably accept the fact that you would at least for a time have to make a livelihood outside the theatre, and probably with an ultimate view of taking out citizenship papers here.

I’m including two letters, one to Larry and one to Hugh Beaumont. [That crossing out is because at first I thought I’d not include covering envelopes; but I’ve decided to send them also, for maximum efficacy.]

As part of my malaise, dear children, I gave up working on the Alcestiad, though it was well into the 3rd Act and was very beautiful. But my ideas about life had changed and I felt it to be sentimental. Instead I’m working on my novel about Julius Caesar, told in letters exchanged between the characters.—and such characters!! Caesar, Cicero, Catullus and Cleopatra!! And that’s what I shall be doing in Yucatán next week. Letters will be forwarded to me promptly from Hamden and I promise to reply promptly and faithfully. Forgive an old bungling misfit of a foster-father; I’m better already and know that I shall be all my better self by Spring.

Write me your thoughts on these things.

Ever devotedly though undeservedly

your old pal

Thornton

P.S. My regards to Wilkinson.155 I rec’d a cable from him and am delighted that he used my name and hope good came of it.

New Orleans, La.

April 1. 1947

Dear Lillian:

It’s a joy to get a letter from you and to think about you.

Now as to this proposal, I don’t say yes or no, but I call your attention to the following points:156

The plot-lines have no real tension. The novel combines two famous well-tried plot motives<:> the Magdalene-Thaïs story (or Fallen woman with heart of gold) and Camille (Fallen woman barred by social opinion from achieving a happy union). But my novel has robbed both of these stories of their popular pull. Chrysis is helpless silent and dies having won a success only in her mind. And Glycerium-Pamphilus story is a matter of waiting helplessly and then coming to very little.

The plot-lines have no real tension. The novel combines two famous well-tried plot motives<:> the Magdalene-Thaïs story (or Fallen woman with heart of gold) and Camille (Fallen woman barred by social opinion from achieving a happy union). But my novel has robbed both of these stories of their popular pull. Chrysis is helpless silent and dies having won a success only in her mind. And Glycerium-Pamphilus story is a matter of waiting helplessly and then coming to very little.

All the characters are externally passive and engaged in waiting. (b) Have you ever noticed that the one costume that always looks phoney and corny on the screen is the Graeco-Roman? Modern man cannot wear that dress and appear real. Think of the “Passion Plays” and the De Mille Quo Vadis, Ben Hur and The Sign of the Cross. The only way to get away with it is by extreme “character” types, like Charles Laughton as Nero or Claude Rains as Caesar.157 Otherwise, everybody looks like dead chromo illustrations of ancient history.

All the characters are externally passive and engaged in waiting. (b) Have you ever noticed that the one costume that always looks phoney and corny on the screen is the Graeco-Roman? Modern man cannot wear that dress and appear real. Think of the “Passion Plays” and the De Mille Quo Vadis, Ben Hur and The Sign of the Cross. The only way to get away with it is by extreme “character” types, like Charles Laughton as Nero or Claude Rains as Caesar.157 Otherwise, everybody looks like dead chromo illustrations of ancient history.

Readers of Andros write me all the time. The thing<s> they like about the book are the descriptions of nature, and the “thoughts” of the characters. Now there’s certainly room for thoughts on the screen, sure,—but they only live on the screen when they are carried by strong situations and strong emotions. Now the Woman of Andros from the point of view of action is pale, muted, and passive. In a novel characters can suffer and meditate, but on the screen wouldn’t it all look dreary and spineless?

Readers of Andros write me all the time. The thing<s> they like about the book are the descriptions of nature, and the “thoughts” of the characters. Now there’s certainly room for thoughts on the screen, sure,—but they only live on the screen when they are carried by strong situations and strong emotions. Now the Woman of Andros from the point of view of action is pale, muted, and passive. In a novel characters can suffer and meditate, but on the screen wouldn’t it all look dreary and spineless?

Suppose you hopped up the plot for the screen. Contrived real clashes between the characters. Then I think you’d run into another danger,—in those unconvincing costumes, no one would believe it. Lots of action and crisis but all looking like wax-works charades or a Sunday School pageant. To bring any vitality to Ben Hur they have to work up a vast spectacle and was there any real vitality? And to make Quo Vadis come alive don’t they crown the picture with a mighty orgy? (In Hollywood I used to have lunch with the script writer who was trying to think up a sensational item to “top” the orgy. I think he ended up with naked women bound to the backs of bulls. All concerned knew that the “story” wasn’t holding the audience, so that they had to inject sensation and spectacle).

Suppose you hopped up the plot for the screen. Contrived real clashes between the characters. Then I think you’d run into another danger,—in those unconvincing costumes, no one would believe it. Lots of action and crisis but all looking like wax-works charades or a Sunday School pageant. To bring any vitality to Ben Hur they have to work up a vast spectacle and was there any real vitality? And to make Quo Vadis come alive don’t they crown the picture with a mighty orgy? (In Hollywood I used to have lunch with the script writer who was trying to think up a sensational item to “top” the orgy. I think he ended up with naked women bound to the backs of bulls. All concerned knew that the “story” wasn’t holding the audience, so that they had to inject sensation and spectacle).

But, dear Lillian, I don’t say yes or no. I’ve always believed that you have a magnificent sense of all aspects of movie and theatre. At various times Pauline Lord and Blanche Yurka approached me about a play from it; an opera for Helen Traubel158 was written from it (she sang arias from it at concerts, but the opera was never put on). I feel that it is just about material for a short novel, some word-landscapes, and some semi-philosophic reflections: to expand it would break its back; to transfer it to the stage would reveal the fact that none of the characters really pull themselves together to do anything until it’s too late; and to picturize it would reveal that it falls into a series of melancholy tableaux.

All this is merely subject to your judgment and intuition. And it comes with

devotedly

Thornton

en route to Mayfair Inn

Sanford Fla.

April 7. 1947

Dear Evelyne:

I’ve known unpublished writers who thought their work was very great indeed and I’ve known unpublished writers who’ve feared they were very bad,—but you seem to be both.

When you ask me for the name of a Columbia University teacher who would read them over—what am I to think? That idea would never occur to a reader<writer> with any self-confidence at all. What made you ask for that? If you are a writer of high originality and power what on Heaven could a Columbia University academic do for you?

I repeat what I told you before—if you are a writer of assured powers the first thing to do is to try and sell it through the usual channels,—that is agent or publisher. It may be that your work is so highly original that they won’t be able to appreciate its merits, but at least you try them first.

I wasn’t condescending to you. I was paying you the compliment of assuming that you would at least begin by sounding out the professional ways of doing things. Readings by Columbia Univ. professors are not professional.

x

Your letter is very angry with me.

I don’t think I deserve it.

But not only is your letter angry at me, but for the second time, you get in some sideways sneers at me. Don’t do that.

If you have a friend whose singing, or painting, or writing you don’t like you either  drop the friend entirely

drop the friend entirely  tell him roundly you don’t like the work, and discuss it as far as he wishes to discuss it

tell him roundly you don’t like the work, and discuss it as far as he wishes to discuss it  adopt the plan of never mentioning the work at all—(that’s what I do in hundreds of cases). But the one thing you don’t do is to let fall passing sneers, like side-swipes, and then go on as though you hadn’t said anything at all. It gives you the appearance of thinking that you are wonderfully superior and smug—and I hope that’s not what you intended.

adopt the plan of never mentioning the work at all—(that’s what I do in hundreds of cases). But the one thing you don’t do is to let fall passing sneers, like side-swipes, and then go on as though you hadn’t said anything at all. It gives you the appearance of thinking that you are wonderfully superior and smug—and I hope that’s not what you intended.

Thornton

As from: 50 Deepwood Drive

Hamden 14, Conn.

Feb 28. 1948

Dear Helen:

I would be ashamed to take up your time with any request of my own, but I am doing it on behalf of a great actress and a gracious delightful woman.

I have just returned from Paris where I saw much of Jean-Louis Barrault and his wife Madeleine Renaud.160 They are at the Marigny—on the Champs-Elysées—having a great success in a repertory which includes “Hamlet”; Marivaux’s <“>Les Fausses Confidences”; Molière’s “Amphytrion”—with glorious scenery by Christian Bérard161; and the Gide-Kafka “The Trial”.

I met them first at a friend’s home and then I used to sit and eat and drink with them after the performances. And I noticed that Madame Renaud had a most unfortunate hand at make-off <make-up>. Off the stage without being classically beautiful, she has a fascinating and endearing face; on the stage (in plays that go into paroxysms about her beauty) her make-up did her every injustice.

Finally, I felt that I knew her well enough to mention it. She received my remarks with gratitude and anxiety. I then told her that I was once present when one of our first actresses gave to another of our first actresses—you to Ruth—your “formula”, worked out from a long experience on both stage and screen. I said that naturally such a thing required great readjustment from person to person, etc, etc. All that she understood. I told her I would see whether such a formula could be obtained. At our leave taking her last words were an imploring repeated “You won’t forget.”

It seems surprising that a Frenchwoman would be so unskilled. I think the explanation is that she rose from the Conservatoire, to the Odéon, to the first place in the Comédie Française and that the French (innovators in so many things; conservative in others) were still passing on a maquillage162 suitable for gaslight.

Mme Renaud is not tall; has light brown hair, and a complexion neither strikingly white nor pink. I think she could adapt any suggestions given to her.

Could your secretary type out that “plan”, together with the names of the ingredients which I would forward to her?

Maybe this is all impractical, but I know you will not mind my having tried to further a good service in the sisterhood of great actresses.

with devoted admiration ever

Thornton

Hamden, Conn.

As from: 50 Deepwood Drive, Hamden,

Conn.

Princeton Inn, Princeton, N.J. en route

April 7. 1948

Dear Glenway:

To be so generously commended by you sets off such a hurlyburly of self-examination and self-reproach, mixed with the delight, as you can hardly imagine.163 I am suddenly reminded of all the negligences and shortcuts, of the fact that I go through life postponing the book I shall really “work at”, as you so dedicatedly do. You are the only writer of our time who sovreignly means every word and weighs every word’s relation to every other. The thought of you reading mine aloud to your friends is very exciting to me because I can imagine you—as good actors do for our plays—subtly repairing balances and tactfully filling hiatuses. To all but the most attentive the book looks like a sedulous array of erudition and painstaking assembled mosaic,—Lordy, it’s what the architects call an esquisse-esquisse,164 an impenitent cartoon. It was, in fact, my post-war adjustment exercise, my therapy. Part almost febrile high spirits and part uncompleted speculations on the First Things.

All this is why it was so warming to know that falling into your heart and mind, you could see all that and understand all that, and yet, as you say, love it. Because with all its incompleteness it urgently asks to be loved. And that so many have denied it. It’s been called frigid,—when its all fun and about the passions; it’s been called calculated,—when its recklessly spontaneous; it’s been called hard,—when it’s almost pathologically tremulous.

This fact that (and about the plays!) everybody “gets me wrong” has made me accept the fact that I’m a very funny fellow. And it extends to my personal self and is reflected in your letter. The notion that a parti-pris165 could have prevented my seeing you in New York is unthinkable. Were you in New Haven, I should be importuning you continually to talk the night out over beer. Why, no month goes by but what I remember and profit by things you let fall at Villefranche,—on Beethoven’s style compared with Mozart’s, an extraordinarily enlightening remark on James’s The Golden Bowl,—those are extraordinary resources and if I were not inertia in person I would long since have travelled far to tap them. But here I am this very funny fellow, glad to drop in at cocktails anywhere in New Haven, speaking at any Veterans Wives sewing circle, if it’s in New Haven; going to New York “on business”, then getting a fit of shyness rather than call up friends, and eating alone at little boites in the West Forties and dropping in alone at whatever trembling pianist may be coping with a début at Town Hall.

Look, for instance, at what I am doing now, and what has delayed my reply to your letter. Idiotic!—I’ve been working all day and far into the night on the chronology of the plays of Lope de Vega (but out of the 500, only those between 1595 and 1610). Passion, fury and great delight. Yes, a compulsion complex. Sherlock Holmes as scholar. I am certainly the world’s authority and can correct all the scholars before me, but cui bono? only 20 people in the world would be interested. It is perhaps my harbor from the atomic bomb. In the meantime, letters mount up; duties neglected;—this is the funny fellow.

Next day—New Hope, Pennsylvania. There are lots of ways in which I’ve watched you these years,—for instance, in those sideshows (sometimes called duties) of an author’s life, prefaces, translations, recommendations, political statements. Next to you, I do it least of our colleagues; and I think you are right that we shouldn’t do it at all. (Ernest Hemingway used to do <it>; he has abandoned it, not however on grounds of principle, I think.) I’m getting a firmer No as I grow older and I often mutter to myself: Glenway Westcott’s right.

This is only one of a score of matters that I would like to submit to you some day. I’m about to be fifty-two years of age, but I still have an enormous appetite for advice; I seek it out and I act upon it; and you have always held for me the character of a sage.

So that’s one of the reasons why your letter was so much more than gratifying, and I thank you a thousand time<s>

Ever most cordially

Thornton

July 5 1948

Dear Max—

Don’t have to tell you how happy your letter made me.

Yes, I by-passed large quantities of the material that, given the title, should have been there,—the political life behind the conspiracy. For that I took refuge in—and overexploited the most exciting element of a letter-novel: the “jumps”, the hiatuses. Similarly, the Girls are harrying me about what they feel to be an omission,—what did Caesar feel about Cleopatra after he surprised her with Marc Antony? To that question I feel, smugly, that I gave the indications sufficiently. But the full picture of why Brutus did what he did I skimped.

x

Max, for over two years I’ve been working on Lope de Vega,—often 10 hours a day in happy contentment. It’ll be a short book “The Early Plays of L. de V.” for scholars only, all footnotes, no “literary” appraisal.166 I’ve been able to date play after play through observing his theatre practice, rôles tailor-made for the performers, etc. But some day I’d love to tell you about himself. At certain periods of his life he was finishing a play about every eleven days. Fascinating to see that the stupifying fecundity proceeded from the fact that he wrote from every motive for writing, good or bad: for money, for prestige, from vindictive competetive spirit (sideswiping savagely his great contemporary Ruiz de Alarcon and cool to Tirso de Molina167), from autobiographical overflow and confession, and of course from intoxication at the multiplicity of character and circumstance.

Mylabors have been sheer PhD work and I should have done it in my twenties, but I’m still living as though we were to live until a hundred and fifty.

That we all wish for you.