AS 1961 BEGAN, THORNTON WILDER VOWED TO WORK ONLY on novels and plays; he stopped writing essays and introductions, and he discontinued giving lectures and speeches. He had several current writing projects in his portfolio as he drove north after spending February 1961 in Florida. The libretto for The Alcestiad opera was completed, and the libretto for the Hindemith opera of The Long Christmas Dinner was almost finished and would be ready in time for its December 26 premiere in Mannheim, Germany. Wilder was also at work on the two series of one-act plays, “The Seven Deadly Sins” and “The Seven Ages of Man,” for the arena stage at New York’s Circle in the Square Theatre, and these manuscript materials were packed in his luggage when he left in March for a two-month trip to Italy, Switzerland, and Germany.

After his return from Europe, Wilder worked on several of the plays at New England summer retreats and continued this writing throughout the fall. There were to be fourteen one-acts in all, but only three were ready to be staged. His “Plays for Bleecker Street,” so called because the Circle in the Square was on Bleecker Street, opened on January 11, 1962. Someone from Assisi was from the “Sin” series and Infancy and Childhood were from the “Ages” series. Wilder kept working on both series, and, as was his habit, he did not attend the premiere. Instead, he was in Atlantic City, helping Jerome Kilty, a young actor/playwright friend, adapt Wilder’s 1948 novel, The Ides of March, into a play. Shortly thereafter, Thornton and Isabel left for Frankfurt, Germany, for the rehearsals and premiere of The Alcestiad opera, which was scheduled to open on March 2, 1962. “An Evening with Thornton Wilder” was held in Washington, D.C., in April. At this event, Wilder read from his work in front of an audience that included President Kennedy’s cabinet and invited guests. Less than a month later, he drove to Arizona to become a self-styled “hermit in the desert,” planning to live anonymously and write for two years. He set off in his car on May 9, 1962, and arrived in Douglas, Arizona, on May 26.

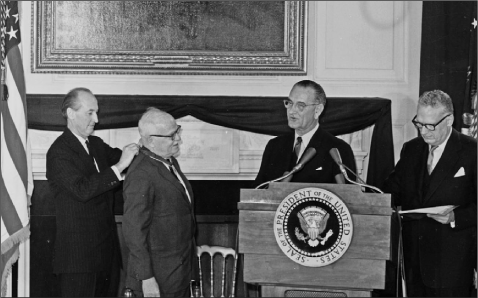

Wilder stayed in Douglas, with occasional visits to Tucson, for a year and a half. While he was working on the one-act plays around Christmastime in 1962, he decided to change course. He began a new novel, which he would work on during his entire stay in Douglas. Since he was unsure at the outset whether this project would continue to flourish, he did not mention it to his sister Isabel until March 1963. He intended to be in Arizona for two years, and he planned to leave only for a brief trip, scheduled for September 1963, when he was to receive the Medal of Freedom from President Kennedy in Washington. The ceremony was postponed twice, once because of the death of the president’s newborn son in August 1963 and then because of the president’s assassination. A new date for the ceremony was set, and Wilder left Douglas in late November in order to reach Washington for the presentation of the award by President Lyndon Johnson on December 6.

Having decided not to return to Arizona, Wilder traveled to Hamden and then went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to attend his brother’s retirement dinner at the Harvard Divinity School and spend the Christmas holidays with his family before setting off in early January 1964 for a four-month stay in Europe. That month, after he had left for Europe, a musical based on his play The Matchmaker opened in New York; the great success of Hello, Dolly! gave the Wilder finances a tremendous boost. His goal during his time abroad was to complete his novel, but he began to realize in April that it would be significantly longer than his previous ones. In May 1964, he booked passage on an Italian ship traveling from Genoa to Curaçao, a three-week voyage that would allow him to continue writing in comfort and without interruption.

He remained in Curaçao for a week before flying to Florida, where his concentration was hampered by the necessity of driving himself around and visiting his aunt Charlotte Niven, who was now living in St. Petersburg. When he reached Hamden at the end of June, Wilder had a routine eye examination and a cancerous mole was discovered near his left eye. He subsequently underwent surgery to have the tumor removed, then spent most of July undergoing radiation treatments. By August, he was pronounced fit enough to resume his travels around New England. By mid-September, he was off to Quebec, and by December, he was able to make the long car journey to Florida.

In January 1965, Wilder was ready to return to Europe to continue work on his ever-expanding novel. Reversing the route he had taken from Europe the previous spring, he flew from Florida to Curaçao and embarked on a leisurely three-week Atlantic crossing, this time to the French Riviera. He spent six weeks writing in Europe, then embarked on another three-week ocean voyage, returning to Curaçao. He was back in Florida by mid-April. May 4, 1965, was the only inflexible date on his calendar that year. That was the day Wilder was due at the White House to receive the first Medal for Literature award from the National Book Committee, which was presented to him by Lady Bird Johnson. After that, he was off to New York to see, for the first and only time, the long-running Hello, Dolly! and, as promised, pose for publicity photos for the show. Early June found him in New Haven to attend his forty-fifth Yale reunion; he remained in Connecticut for most of the summer, working on his novel, and then spent several weeks in August with Isabel on Martha’s Vineyard. With the manuscript of his unfinished novel in tow, Wilder sailed for Europe with Isabel in October. They stayed three months; in early February 1966, Wilder embarked on his now-preferred leisurely ocean voyage from Genoa to Curaçao, then flew to Florida, where he spent three months writing.

upon his return from Florida, he spent a short time at home in Hamden, then set off to writing retreats in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and Quebec. He spent August 1965 in solitude at New Haven’s Hotel Taft before joining his sister on Martha’s Vineyard for September. When Wilder traveled, he could set the parameters of his writing and social life. This solved the difficulty of declining invitations and offending friends and family. As a solitary vagabond, he could also make the abrupt changes of locale that sometimes helped to stimulate his thought processes when he felt stymied in the midst of his work. Wilder had been working on his novel full-time since January 1963, and now it was almost completed. At the end of October, he returned to Europe, visiting Paris and Munich. Then on November 26, 1966, in Innsbruck, Austria, he signed off on the proofs of the new novel, The Eighth Day. He spent Christmas in Switzerland, traveled in Italy, then sailed back home and arrived in Hamden a few days before the March 29, 1967, publication of the novel, three weeks short of his seventieth birthday.

After the publication of The Eighth Day, Wilder retired to Martha’s Vineyard for two months. He wrote for several hours each day, trying to find the ideas and imagine the form that would shape his next creative venture. He changed his locale at the end of June, traveling to Stockbridge, New York, and New Haven, then returning to Martha’s Vineyard in September, where he and his sister bought a house. Wilder stayed on the island for the month of October, still with no definite writing project in mind. In November, as was his custom, he returned to Europe for the winter months, and, unusual for him, spent more than a month in Paris. Isabel joined him there for Christmas and then they left for their regular haunts in Switzerland, Austria, and Italy. While he was abroad, Wilder learned that The Eighth Day had won the 1968 National Book Award for Fiction. It had been on the New York Times best-seller list for twenty-six weeks.

He did not return to the United States for the ceremony; his thoughts were focused on the future and on his next “real right” writing project. He continued to write, as well as reading, rereading, and annotating the books in his collection, whether an old copy of Goethe’s poetry, a volume on Kierkegaard’s philosophy, or a new paperback treatise on linguistics, archaeology, or social science. Wilder was particularly interested in the authors whose fiction and nonfiction works informed or influenced the thinking of young people coming of age in the 1960s. When that generation challenged established social institutions and practices, he observed with interest the civil rights protests, dissent over university governance, and demonstrations against the Vietnam War, attempting to interpret these events in a more inclusive, universal context. This was especially true during the summer of 1968, when he was recuperating on Martha’s Vineyard from a long-delayed hernia operation. Wilder recovered in full and, like clockwork, was off to Europe in November to remove himself from interruptions to his writing life.

These periods abroad were as important to Wilder as the slow ocean voyages to get there and the hotel rooms he lived in; he considered the ships and rooms his “places of business,” his essential workplaces, his “offices.” This way of living was modified in the next few years, however. Soon after Wilder’s fiftieth Yale reunion in June 1970, he began to experience serious vision problems. In late June, he learned that this was a circulatory, rather than an ocular, problem. He was suffering from hypertension, and because his sight was reduced to some degree, he was advised to limit the time he spent using his eyes. During the almost three months he was in residence on Martha’s Vineyard, an additional ailment—severe back pain—also limited his activities. In the late fall of 1970, accompanied by his sister, Wilder took his last trip to Europe. Since he was no longer allowed to live at high altitudes, they spent the two months of their stay mostly in Venice and Cortina, Italy. They also went to Innsbruck and Zurich for a short time before returning to Italy, where they stayed in Naples. Wilder worked four hours a day, despite the problems caused by high blood pressure, poor eyesight, and intermittent deafness. He was on the brink of an idea for a new novel.

More than two years before, in February 1968, in Europe, he had begun a semiautobiographical, semifictional series of sketches drawn from different stages of his life. He continued to develop the separate pieces during his international and domestic travels thereafter. Now that Wilder’s journeys were limited to low altitudes, he spent the winter months each year in New Mexico, Texas, and Florida. When he returned to Hamden in the spring of 1972, the “real right” idea coalesced. He envisioned the protagonist for a projected chapter of his memoir as the hero of an entire novel, one devoted to his adventures in Newport, Rhode Island. Wilder began and finished this novel, Theophilus North, in his seventy-fifth year, writing it from April 1972 to April 1973. His final book, it was published in October 1973.

He began work on a sequel, which he was calling “Theophilus North—Zen Detective,” even as he was plagued with increasing health problems: a slipped disk, increasing blindness, continued high blood pressure, breathlessness while walking even at an unaccustomed slow pace, and, in September 1975, an operation for prostate cancer. Despite his poor physical condition, Wilder remained the same energetic and cheerful conversationalist as always, particularly at Thanksgiving dinner in 1975 in New York with his old friends Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin. That holiday week in the city proved tiring, however. He returned from New York on December 6 to his home in Hamden, “The House The Bridge Built.” On December 7, still feeling tired, he took an afternoon nap and died in his sleep of an apparent heart attack.

June 25. 1960<1961>

Dear Mr. Rorem:

Many thanks for your letter and interest.1

Sure, I’d be proud to have you find something there that you could set to music.

But I’ll have to ask you to wait a year.

There are three operas now being written to words of mine—and probably a fourth which has been pending a long time. This constitutes a sort of glut. I wouldn’t mind it, but the first two composers take the view that it diminishes their chances at getting a hearing, or some reservation like that.

If, after a year’s wait, you should still be interested, I would be inclined to ask you to consider the question as to whether it is worth your while to set to music such brief pieces. Those three-minute plays were more planned as dramatic exercises or sketches—than as practical theatre-pieces. I’m inclined to think that drama (and musical drama) doesn’t really begin to work under half-an-hour. But I’m not certain about this and we can discuss it later.

I wish I could suggest something for you to work on, in the meantime. I’ve never heard of anyone setting Edna Millay’s Aria da Capo2 to music. More and more I hear of productions, here and in Europe, of those fragments (imitation of an American revue) grouped around T. S. Eliot’s Sweeney Agonistes3j

I’m sorry this letter may be a disappointment; I hope it’s only a delay.

All cordial best wishes.

Sincerely yours

Thornton Wilder

July 25. 1961

Dear Miss Niemoeller:

Late in life I have taken a great interest in the Noh plays—first through Fenollosa and Pound.5 A Japanese translator (of my work) sent me as a present a most satisfying selection with a rich annotation. It’s a very great manifestation of theatre.

And I wish I had known it earlier in my life. My plays may seem to reflect some elements of Chinese and Japanese theatre but—in spite of the years I spent in the orient as a boy—I have not been aware of any influence prior to the ’40s that could derive from the East. My use of a “free” stage has other sources. (To this day I have never seen a Noh or Kabuki performance—and no Chinese theatre except that program of “selections” which Mei Lan Fang6 gave in New York in the 30s.)

My admiration for Noh was first caught by Claudel’s account in L’Oiseau du Soleil Levant (have I remembered that title correctly?)7 but by that time I had already written the plays you name.

No, I never met Copeau8 or Claudel.

So all I can say is that I deeply regret that I had not known Noh earlier. The six devices you list can also be found in other forms of drama. What I would have borrowed would be

the two-part drama—real, then supernatural.

the two-part drama—real, then supernatural.

the device of the journey

the device of the journey

the relation of protagonist and chorus-observer.

the relation of protagonist and chorus-observer.

the ideal spectator seated in the audience

the ideal spectator seated in the audience

the entrance of the Spirit across a “bridge”.

the entrance of the Spirit across a “bridge”.

perhaps the use of quotations from classic poetry

perhaps the use of quotations from classic poetry

All cordial best to you in your work

Sincerely yours,

Thornton Wilder

P.S. Both the addresses you give are very near my birthplace—heigh-ho 64 years ago

TNW

Sunday eve

August 27 <1961>

Dear Labor-Day-Week-End Merrymakers:

Look at where I am!

In a temple of sheer romance.

Time stands still here. Down the corridor Miss Ruth Gordon is studying the new act-ending for Saturday’s Children. Down another Garson Kanin is worrying about whether Judy Holliday can replace Jean Arthur. …Tallulah is screaming at Michael Myerberg. (A few years later she is (in The Eagle has Two Heads) throwing “that Marlo Brandy” out of the cast) and a few years later I’m sitting on the floor in Gadget’s suite after the first performance of Streetcar and Brando looks in the door for a minute with supreme contempt at all us effete intellectuals.9

Sheer romance.

x

I’m going to evoke delighted pictures of you all in the penthouse of The Sands at Las Vegas; but I’m going to congratulate you that I’m not there.

There’s an old almanac saw that “the friends of friends are friends.” Nothing is less certain.

Alec tried to endear me to Neysa (a frost), to Cornelia Otis Skinner (a freeze); but to Alice Duer Miller (soul-mates)*

*And we’re all indebted to Alex for Gus Eckstein who met him through Kit?12Sibyl tried to kindle a congeniality with Vita Sackville-West and Miss Mitford (arctic); with David Cecil and Cecil Beaton and Morgan Forster (not a vibration); but with Max Beerbohm (the flowers of friendship). Gertrude took this kind of lamp-lighting very seriously and suffered at her failures: who could like Bernard Fäy or Sir Francis Rose?10

The reason I don’t mix well is because I’m a “confiding nature.” Hence I fall silent when there are more than five people in a room. One can’t confide one’s tentative notions to a roundtable, to a circle; nor—save very exceptionally—to <a> new acquaintance.

Enuff.

x

I hope I thanked you ringingly for the delicious dinner at Cote Basque and for the joy of seeing you—and Ruth so adorable in that dress (at the time I groped to describe it—the word came to me later: isn’t it “eyelet” embroidery, or something like that?)

x

Folks, after your quoting—on the phone—that wish of George Brush,11 I went downstairs to see if I had a copy. Yes, there it was. I certainly haven’t looked into it for 25 years. I read it. Long passages I seemed never to have read before. I must say I think it “holds”. Second, I was reminded of my feeling soon after writing: it could have been a longer book and each episode could have been longer. My passion for compression sure had me in its grip. It actually cries out for expansion—legitimate expansion to make its points. Thirdly, what a sad book it is! Fourthly, how the Depression hangs over it like a stifling cloud.

After Gertrude Stein continued her journey—having stayed 2 weeks in my apartment at the university of Chicago—she wrote from some place like Cornell:

“People tell us you have published a new book. Why did you not tell us you had written a new book. [No question mark.]”

So I sent the book—that book.

“We have read your book. Yes, in the middle it has balance. It is such a pleasure when a book has balance. Yes, I can say that in the middle it has balance.”

And, rereading it, I became aware of the moment when the book swung into balance. And the whole damn thing would have been in balance if I’d let it ride more easily and not tried to be so sec13 and compressed and drastic. I should’ a reread Don Quixote—of the relaxed free rein.

Lots of love

Thornt

Oct 14. 1961

Dear Herr Helmensdorfer:

Yes—long before I met M. Obey I had been deeply impressed by those first two plays he wrote for the Compagnie des Quinze,—Noé and Le Viol.15 But I never saw either of them in French and for several years I was not even able to find a copy to read. The Professors don’t always realize that literary influence can be propagated by the slightest of intimations: I had merely read brief accounts of the plays and of their productions. (Similarly I was deeply influenced by Paul Claudel’s account of a Noh play long before I was able to read one—if it can be said that any Westerner can really read a Noh play.)

Michel St. Denis’ method of staging—as I read about it—was also a large part of this influence: the treatment of Noah’s Ark—the fact that Tarquin prowling through the house walked merely between posts set up on the stage; the figures of the two commentators—all that was very exciting to me and led to my writing The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden, The Long Christmas Dinner—and later the longer plays.16

It was years later when I had dinner with M. obey one night in Paris, the recollection of which is of his great distinction of mind and spirit.

I send all my cordial wishes for the success of your production.

With many regards,

Sincerely yours

Thornton Wilder

In festo sancti

Valentini 1962

<February 14, 1962>17

Dear Louise:

Where there’s a will there’s a way.

I went to the Captain and said:

“Captain, the Atlantic Ocean’s awfully wide. There’s a letter that I’d like to get to a certain party in Europe. And I can’t afford radio-telegraphy. Can’t you think of some other way?”

“Well, let me see.—They’re training porpoises and sea-gulls; but they haven’t quite taught them yet to read addresses.”

“Oh!—Aren’t there some inhabited islands we could stop at? The Canaries or Ascention?”

“Look here, Mr. Wilson, since you’re so serious about this, I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll make a left turn and stop at Halifax in Canada. Would that suit you? I won’t mention it in the Log—see what I mean?”

“Put it there, Captain. You wait and see if I don’t always cross on the Dutch Line.”

“Are you and Miss Watson comfortable?”

“Oh, yes. My sister has her bed-board and I have my… a-hem… basins… I have only one very small criticism to make… I’ll keep my voice down to a whisper: the orchestra doesn’t quite play in tune.”

“You don’t say!! I thought they did the Potpourri from Madame Butterfly very nicely”

“Oh, that.—Yes, all those quarter-tones and super-imposed keys added a certain interest that isn’t always there. But in that place where the Geisha says that some day Lieutenant Pilsbury18 will come,—you know, there’s real pathos there: because I doubt if he could find her.”

“How do you mean?”

“Well, Captain, it’s like your charts. He’d be looking for her in E-Flat and she wouldn’t be there.”

“Why, Mr. Wesley—where’d she be?”

“Well, today I got the impression she was out shopping, at a considerable distance, too.”

“Well,” replied my Captain, drying his eyes, “there’s nothing like those old Japanese myths to move the human hear<t>: Madame Butterfly and The Mikado … and Japanese Sandman.19 Now, Mr. Williams, I’ll stop in at Halifax, if you’ll do something for me.”

“Yes, indeed, I will. What is it?”

“I want you to sit at my table so we can have some more meaty conversations like this. You can’t imagine the amount of drivel I have to listen to. And: in that letter of yours that we’re making this little detour for—be sure you put some more of this good sense into it—and this inspiration… How… how did you plan to end your letter?”

“I thought I’d simply say

‘with love,

Theodore.’”

Last days in Frankfurt

March 13. 1962

Dear Cass:

At everything I do these days I whisper happily to myself “for the last time.”

Last lecture, last class, last “dinner coat”, last première, …. its a great feeling. By mid-May I shall be in the desert of Arizona, … loafing, cultivating my hobbies (Lope de Vega, Finnegans Wake, Shake-speare)<,> learning Russian, refurbishing ancient Greek… And after a while, doing some writing. I should have retired long ago.

An odd thing happened at our opera-première here—unprecedented ovation… curtain calls for 19 minutes. The composer Louise Talma naturally elated …then in the next few days the critics’ reviews: none denied her mastery of means, but all but two have been severe. These things don’t affect me (an old battered ship) but it is especially hard for Louise with her first large work and coming after that undoubted appreciation by the audience.

Rè Goldstone. A friendship picked up in officers’ messes in the army. Well, I tried to be obliging. I submitted to the Paris Review thing groaning; but most of it was from tape and many answers I submitted in longhand.20 But I told him that that was to be all. Imagine my horror when I heard that he was writing to old friends (Bob Hutchins and Harry Luce etc) for character sketches etc. Hell’s Blazes!! What could be more mortifying. And for them to think that I was behind it—gloatingly waiting for any pretty things they might say about me.

I’ve told Goldstone over and over again that I won’t have it. But he has the skin of a rhinoceros. All his fellow-profs at N.Y.U<.> are publishing—have gotta publish. And he’s got his teeth set.

I won’t help him one inch.

And I’ve written several friends to slap him down.

If there’s ever to be a book about me (and what an uneventful putter-putter book that will be) let Isabel do it. It’s not any harsh truths that I mind, its the unfocus’d admiration of a Goldstone—which also contains almost unknown to himself a good measure of animus,—especially now when I’ve had to treat him so badly.

Anyway books about living persons are inevitably porous—I helped Eliz Sergeant chapter by chapter through that book on Frost21 and a woeful task it was.

I’m going to Berlin next Saturday (I’ve always admired the Berliners) and shall give a reading (my LAST) at the Amerika Haus. Thereafter “I have one more river to cross Oh Lord”, I’ve go<t> to go to Washington for a “Wilder Evening” (confidential) before Certain Listeners.22

THEN … Oh, Glory. … The cactus and the rattlesnakes. I’ll be away about 2 ½ years and then return 20 years younger and with a portfolio of stuff for Master Harpers.

All cordial best to the House.

Ihr alter Freund23

Sagebrush Thorni

March 18 1962

Dear Irene:

Oh, it’s awful; oh, it’s shameful, I’ve owed dear Irene a letter for so long. FIRST, to thank her for the Empson book.24 I revel in it; I read it over and over. I don’t agree with every word; time after time he’s the outrageous enfant terrible. He gets Milton’s God mixed up with the God he revolted against in some Church of England he was forced to attend when he was 12. But he’s so full of ideas—of splendid digressions—of gallant crusades (for Dalilah, for example). It’s about time he settled down from all this flambouyant Don Quixotism and did another really focus’d book, but until then I’ll joyously follow him across heath and jungle slaying beasts real and imaginary.

Now—you’re to do Lady Macbeth “most of the year” in Stratford25—and what else? You shouldn’t pine to do his Cleopatra. It’s not grateful; it only looks grateful. The play should be called Antony and Octavius. Shakespeare was much more interested in that scene of the drunken triumvirates on the boat than in the amours in Egypt. With “Cleopatra” in the title no wonder directors have to scissor scissor the last act. Won’t they let you do A Woman Killed with Kindness? Or a restoration or Lady Teazle?26

I hope you got some pleasure out of the Elizabeth in Rome27 and that there are some passages in it where I can cry out “Theres Irene actin’ great.” And tho’ it’s incidental, I hope you had many a feast in Rome—of art and of knives-and-forks—and of good talk.

Maybe you’re in London now and Isabel has been seeing you. In which case you’ll know our news but I’ll sketch it lightly.

With our opera we had the damnedest experience. The House gave us all we could ask for: five singers (led by Inge Borkle)—a noble conductor—countless rehearsal hours (the score is devilishly difficult) and the première was followed by an unprecedented ovation—19 minutes—over 40 curtain calls. Naturally, Louise thought this was IT. Then in the next few day<s> the region’s critics: cool to worse. To be expected we were told by the Director: an opera by an American! … by a woman! … by a composer of French background i.e. understatement of big situations instead of the Wagnerian-Straussian soaring-racket. Now the reviews have begun to come in from farther off—Zurich etc… much more favorable especially to the stature of the music. And the public is filling the house (I heard the first three) and the silence during the big scenes and the applause is very real.

But, damn’it, those reviews have so far prevented other opera houses from picking it up and a Publishing House from adopting it. Damn, damn, double damn. Anyway it is beautiful music and in time it will be rediscovered.

I shall soon be far away. Farewell, O world. Arizona desert—2½ years. A bum. Loaf, read, learn Russian, polish up my Greek, do Lope de Vega and Finnegans Wake … and finally start some writing of my own. Go for weeks without saying a word (oh blessing) except buying avocado pears and helping to close bars at 2:00 a.m.

But before I plunge into this long-delayed obscurity I’ve been splashing like a seal in its reverse. The Russians wouldnt dare encroach on Berlin while this publicity-mad hostage is here. I’m dining with General Clay28 tonight and reading from my works Tuesday to autograph-frantic maenads. I’ll bet you’re raising and lowering your chin and muttering “Old Thorny thinks he likes solitude and cactus, but just wait. … he’s the biggest popinjay in the puppet-cabinet; he’ll be back from his sandpile from<in> two months calling attention to himself like a blasted Rubirosa.”29

Berlin is fascinating in itself but oh the art treasures in the Kaiser Friederich-Museum, beginning with the Nefertite.

Lots of love

Thy

Sagebrush Thornt’

S.S. “Bremen” approaching New York, March 30. 1962

Dear Glenway:

I hope you felt sort of more free knowing that T.N. would postpone reading your words until they were freed from time and place—like those rooms which we once lived in and loved but into which other people have moved; they are ours in the truer if not in the literal sense.

Anyway, I knew you understood.

Isabel thinks very highly of them and says there are some pages about the very nature of the novel that I am greedy to read.30

x

The older I get the more things I find funny. I really ought to grow a pot-belly and resemble those ribald drunken old poets that are pictured sitting under cliffs and waterfalls on Chinese wall-hangings.

x

For instance: I ask a woman to write an opera with me. This seems, after Dame Ethel Smythe,31 to be the second time in all history that a woman has set out to write a real “grand” opera. The sound sturdy musicians in the orchestra pit at Frankfurt took a sardonic view of all this. And they engaged in a furtive conspiracy—not to sabotage the work; that’s not German, that’s French and frequent there—but to test her out. But Louise Talma is métier to her fingertips (acquired under that terrible whiplasher Mlle Boulanger32). Louise stops the piccolo-player in the corridor: “You did that high trill on C splendidly but what was the matter with the G-sharp iterations?” “Gnädige Frau, it’s not playable.” And she showed him a fingering. Things like that get around. The conductor asked her to show Percussion a certain riffle on the snare-drum. And finally they were playing like angels. Why is it that I find such things funny?

x

And. So it gets around that I plan to go to Arizona to be a hermit—without shoe-laces necktie or telephone.33

Well, the realtors swamp me with offers of 20 room houses in 40 acres with swimming-pools. (The letters are full of facetious remarks to show that they know, too, the Bohemian side of life.) A woman offers me a ghost-town which she had won in a contest from the Saturday Evening Post. … This is absolutely true … It had been called Stanton but the Post changed the name to Ulcer Gulch and so it is called now on the map…. A woman offers me a house where she had been happy with the husband who designed it: it is in the form of a star for aspiration and a spider web, because the spiders are the greatest of all architects. There is no square room in the house, but there are four bathrooms.

It’s not hard to see why I find those returns funny.

x

Less amusing is that they stage a play of mine about St Francis … I wanted one almost blind, toothless, but a flame of happiness; and they give me a man who could be a full-back on the Indiana football team tomorrow and who has just risen from mountains of corned beef and cabbage.34

x

So you’re working on the Odyssey—that’s one of the things I’m to do in the desert: renew my Greek. The widow of Karl Reinhardt has just given me his posthumous book Die Ilias und ihr Dichter35…The conjectures of scholars about the layers… the growth of its structure… The lost epics which it reflects… This book all the richer because it is made up of notes written over many years which he did not live to re-shape into a stately volume.—the immediate insights of a great scholar. Not funny, but fun.

x

Please share this letter with Beulah36… under her grave glance is concealed a boundless capacity to find things funny—especially young chaps from Wisconsin

like

your devoted old friend

Thornton

May 17. 1962

Dear Louise:

Delighted, delighted about the Colony. tho’ it would have been “fun” to think of you here in August, both Isabel and I were concerned about some of those crushing days that can descend on us here.37 (Yet, too, there can be halcyon days for a week on end, even in August.)

L. Bernstein,38 whom I recently met “in society” will be at the Colony. What do you think of that? Are you going to tell him right to his face that he’d better re-contemplate Beethoven?

Oh, I’ll betya he’ll be charmed by you—transported—and things will come of it that’ll almost persuade me to buy an air-ticket and fly east. Remember my prophecy.

x

So you want to know what the Washington “do” was like?39

What did I talk about with M. Malraux.

I talked about “good evening” and that was all—and not even in French.

Gracious sakes, there were 162 guests.

The high points for me were  meeting Scott Fitzgerald’s beautiful “Shakespearean” daughter who remembered a walk we took in a rose-garden when she was eleven40

meeting Scott Fitzgerald’s beautiful “Shakespearean” daughter who remembered a walk we took in a rose-garden when she was eleven40  meeting Balanchine and telling him, plump, in his face all that I owed to him and

meeting Balanchine and telling him, plump, in his face all that I owed to him and  the President in the handshake line saying: “I want to thank you, Mr. Wilder, for what you said about last week” (at my “reading” in the State Department.*)

the President in the handshake line saying: “I want to thank you, Mr. Wilder, for what you said about last week” (at my “reading” in the State Department.*)

The greeting line was alphabetical and we were a nice little contingent in “W”s: Penn Warrens,41 Wilder, Tennessee Williams.

I sat at the Vice President’s table with Alexis Léger, Mrs Lindbergh, Mrs Bohlen, Robert Lowell.42

The first Lady was glorious in a white and pale raspberry Dior.

The food (Vendredi, maigre43) was perfect.

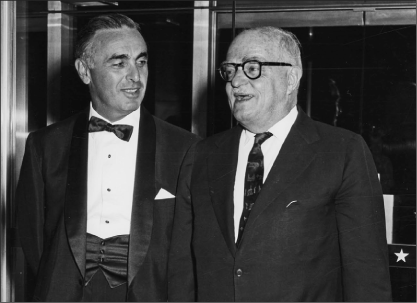

TNW with Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Abraham Ribicoff on April 30, 1962, at the State Department, where TNW read excerpts from his work to an invited audience.

TNW with Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Abraham Ribicoff on April 30, 1962, at the State Department, where TNW read excerpts from his work to an invited audience. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Stern-Rose-Istomin44 played the Schubert E-flat superbly but the audience, excited by all that glamor and a little tight, did not behave as it should. (I sat by Mrs Sam Behrman45—and a lovely person she is—who is Jascha Heifetz’s sister.<)> We listened. Lenny was the only musician there—they having been at the Casals night. I finished the evening at the Francis Biddles46 with the Edmund Wilsons, the Saul Bellows, Balanchine, and Lowell.

Fun?

A little contretemps took place involving our hosts which I will only tell you in confidence in 1965 (not involving me, deo gratiâ.)47

I start driving west Saturday. Don Quixote following his mission. Friday I go to Long Island to see Charlotte.

I love the Rumpelmeyer passacaglia.48 What a girl! I suppose that the surpassing difficulty is in allusion to my rusty old steps on the parquet. Oh, how often I shall think of those Frankfurt days in my new home and it’ll all get more and more lyrical. And all on the tide of the rich right flowing music.

love

Thornt’

<Douglas, Arizona>

August 26. 1962

Dear lsa—

This letter’s for Aunt Charlotte,49 too, but prepare her for the insubstantial bulletins I’m reduced to.

Tonight, having eaten without break six of my own meals I drove over to the Copper Queen Hotel in Bisbee for dinner. I went all that way to get the sirloin steak and the salad. I don’t like steak or lettuce (who can?) but a little voice kept saying I ought to, I should.

Now that I’m housekeeping I’m getting to be really like that smalltown eccentric that I envisaged, and described to you in Patagonia. To get the paper—the mail—a little food-shopping is the only thing that takes me out of my room. That’s not right.—oh, I go out to drive—and glorious drives they are; I meant: to walk.

x

Girls<,> enough has not been said about the dangers of the kitchen. Several times I’ve almost lost an eye from far-spitting fat; and that lifting hot water from one place to another. I think a campaign should be made to warn us beginners. When I eat out, Sammy’s or The Embers at Buena Vista and see all these brides (nicely nurtured girls who’ve married engineers in the hush hush Establishment—three children by the age of 25 but still brides) were they warned about this. Don’t I remember our own mother—in Man<s>field Street days, and maybe in Mo<u>nt Carmel—always having accidents and cicatrices? Aren’t I right about that? Please reply.

x

What do I like most about cooking? The various ways of doing eggs.

What do I hate most? Washing and drying drinking glasses. (That’s because I inherited from both the Wilder and Niven side a compulsive perfectionism. I can never believe that the glass is clean and dry.)

What do I hate most about my kitchen as a work-place? Damn it, the four pilot lights. They’re not, as in Deepwood Drive, unobtrusive little beacons; they’re actual flames. At night they’re four big eyes. And—in this weather—they’re enough to heat the kitchen in themselves. You could fry an egg on them in 10 minutes—pfui!

What do I like most about my kitchen as a work-place? Why, the frigidaire. I moon about it. I dream about it. I think of all the workers for 10,000 years to whom it would have been a miracle. You remember my feeling about the obtuseness of Delia Bacon50 (noble Christian woman) letting her Noras and Hilda’s deform their bodies by stooping over those damnable washing troughs—so I think of the labor saved now … let’s not talk about it. Let’s just be grateful. And the money saved—when every dime meant so much in the mid-west and in these states.

x

Dear Aunt Charlotte I wonder what it’ll be like when this letter reaches Hamden. The social interchange won’t have begun (thank you, I don’t miss it yet); I hope the weather won’t be oppressive still; (it’s accablant,51here). I wish I could show you the acres of houses for retired people, like you and me, under the shade of these great mountains—acres, yet they in no sense crowd the landscape—the Biblical desert remains as on the day when Jacob worked for Leban and his two beautiful daughters.

x

I’m saving this letter to mail it when it will arrive when you do. Lots of love to both of you, from your vagrant

Thornt

Sat’dy Sept. 8. 1962

Dear Aunt Charlotte =

Sunday’s my day for writing to Isabel, so I don’t have to work until tomorrow.

One of the first things to know about a hermit is that he hasn’t much to say. I’m perfectly content in my thébiade<thébaïde>.52 Every now and then I get a faint twinge of nostalgia—for Martha’s Vineyard and for the New England road; but then I take a sunset drive on my glorious desert and the uneasiness abates.

This is a very nice town of a little over 5000. Wide streets; one and a half with shops. We’re right on the Mexican border and we’re at least 50% Mexican descent ourselves. The Junior High School is catty-corner from where I live and the several hundred children who collect at 8:30 under my window are at least that per-cent of Mexican descent. There is no hoodlumism here among the working class; that’s only at the top. The head of one of our chief banks has just had to go to prison for peculation.

The signs of frontier are all around us. Ready courtesy and much reserve. A real deference for women, immediately recognizable as different from big city politeness. As frontier, very church-going. A leaflet was giving<given> showing me 36 churches in Douglas and immediate vicinity,—includes Spanish Baptist and Methodist and all sorts of cult churches and, of course, Mormons. You would go to St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church.

We’ve just lived through July and August which I’ll try not to do again. It’s the rainy season—very little rain but mighty thunder and lightning every day—and humidity with the great heat.

But on the whole, I chose better than I knew. As far as I know only 4 people in town know “who I am” and they don’t spread it. About once a month I go to Tucson (250,000) for a few days, partly to visit the University library.

Im “getting well” so fast that maybe my retirement from civilization may not be as long as I first thought it would be.

I am very eager to look over your retreat.53 It’s certainly much prettier than mine which just escapes looking like a barracks or even a tenement. But we have two tall Lombardy pines at our door like sentinals. I’m just getting to brief-chat relations with some of my neighbors,—an arthritic lady on the first floor who’s reading W. Wilkie’s One World54 and a retired engineer who can only walk from the porch to his room. We have young couples too, teachers in the schools here. But I’ve made a resolution not to “get friends” with anybody for a year; so to my own surprise, I’m curbing my natural tendancy to expand. Have a good time in New England, dear Aunt Charlotte,—and when you rejoin your car—drive carefully.

I wish you could see the Y here—its the busiest place in town and the YWCA in nearby Bisbee is the second most imposing building in town. The town used to be much bigger than it is now—the fortunes of mining have made and unmade regular cities out here.

Lots of love

always

Thornt

General Delivery Douglas, Arizona—

Sept. 12. 1962

Dear Elizabeth:

Delighted to receive your letter. You dont mention when you are going home so I assume that you will stay on in Peterborough through September.

Yes, it must be “costing” to recall in writing (which is a higher concentration than reverie or conversation) the days of early childhood.55 Gertrude Stein said: “Communists are people who fancy they had an unhappy childhood” i.e. the same people who can imagine themselves in a social order where nothing is ever ever wrong are the same people who can rewrite their past and declare that they went through years when nothing was ever ever right. It seems to me that the early years can be interpreted both ways: since neither memory nor prevision has begun to operate<,> the heavens and hells alternate without relation to one another.

I recently read the two volumes of Lawrence letters56 (sent me by their editor Harry Thornton Moore—a pupil of mine at the University of Chicago.) I read the second volume first, partly because it contained reference to many people I have known, and because I assumed that the maturer letters would be of greater interest. But later I was to find that the first volume was far superior. How I envied that youthful bull-in-a china shop way of talking straight truth. (Oh, how often I should have done that—even though my view might have been wrong: the honesty in intention would have saved the venture; and from time to time I would have been, valuably, both honest and right.)

D.H.L was in those early novels a great novelist; but there was one serious dead-weight they had to carry. English women—through their situation—have not been “interesting” for a century and a half. They can’t be; their bringing up has been so stifling. I’ve always said that English actresses always behave like vicar’s daughters at a garden-party where the Duchess is expected. The only actresses that count over there from Mrs Patrick Campbell, Meggie Albanesi;57 to Edith Evans have had the redeeming drops of Jewish Italian or Celtic-Welsh blood. Women in Love is a fine novel—, but those two girls (Miriam?) are constantly reflecting Nanny-training. And I bet they were physically cumbrous. Any way all you have to do is to think of Anna K—or Emma B—or Natasha R—or to go back <to> Jane Austen’s. (Dorothy in Middlemarch shows the transition.)

There’s little to say about me except that I should have done this long ago. From time to time I get a pang for friends and conversation and music, but all I have to do is to take a late afternoon drive into this glorious desert and the velléité58 abates. It’s taken several months for the cobwebs to dissipate, but they’re going—and little steady excited work-hours are beginning.

Since you don’t mention your health I hope I can gladly assume that you’re much better.

Will portions of the work you’re on appear in periodicals? I’m to have something in The Hudson59—way off next January; but it’s the University of Texas Review that pays—well, Texanly—and for sheer disinterested belles-lettres,—with a special interest however in that South West.

¶ Now that I’m housekeeping a whole new field of curiosities has swung into view. The fact that I don’t know a thing about cooking is a positive advantage: I improvise; I make advantage of ignorance. My deep regards to the Kendalls. Blessings to you and to your working hours

love ever

Thornton

As from: 757 12th St. Douglas, Arizona.

[Tucson, Arizona]

Dec. 10. 1962

<appeared perpendicularly in left margin>

¶ I told you, didn’t I, that I found an allusion to Peperharow in the new edition of Boswell’s Journal etc of Dr. Johnson in the Hebrides?60

Dear Les Grands:

Selah!

Lobet den Herrn!

I’m up in the big city for a few days to buy Christmas presents and—gee whillikers!—for a practicing hermit the ado of a city of 200,000 is abrutissant.61 I return to my cactus stretches tomorrow. And, Eileen, to my own housekeeping, because my cooking though still modest, is improving.

There’s not much I miss in The East (“civilization”) but I do have other hankerings. I found myself with a longing for the sea and I drove for a day to reach Guaymas, in Mexico on the Gulf of Lower California, known to the Mexicans as El Mar de Cortéz. I was there almost two weeks and never grew tired of watching the waves come in as they did “before there were any of us around.” And now (you’ll think I’m frivolously restless) I pine to stand amid falling snowflakes.

x

Roland! You’re going to stage The Matchmaker! (I wrote most of it in this very Tucson under the name of The Merchant of Yonkers some 24 years ago.<)>

Well, here are some reflections.

You may find it too long. I wouldn’t know where to cut it, but don’t cut it by racing the three main dialogues between Dolly and the Miser (Heavens! I’ve forgotten his name!) Especially, not the dinner scene: it may give the effect of being rapid but an actress would lose her grip on it without calculated pauses followed by fresh attacks and changes of tone.

The longest laugh in the play has to be artfully watched. It’s where Cornelius creeps on hands and knees into the “armoire”. Have Dolly Levi perfectly motionless as she watches him; that builds up the “comedy” of I’m-going-so-self-effacingly-that-I’m-invisible. Don’t get worried if the audience doesn’t laugh at first and don’t hurry it. The laugh should build and last until he’s completely hidden in the cupboard.

The other big laugh requires a most expert actor: it precedes Melchior’s monologue. He starts to return the newly found purse to Cornelius. … Then half-way across the stage, turns and says to the audience “You’re surprised?” The audience falls apart—partly, I think, surprise at being addressed directly—so that actor must do it very real, sin cere … Implication: “you thought I was a low bum who’d certainly keep any money I found in public places.”

I hope you remember Ruth Gordon’s wonderful reading <in> Act IV to Vandergelder (now I remember his name)…“Horace … I never thought I’d hear you say a thing like that!!” Surprise—laughter—warmth. It lets the audience believe that they can be happy with one another. LOUD impulsive and very sincere.

I don’t know what sweet old-fashioned melody you’ll use for “Tenting Tonight” in the Cafe scene, but be sure that it’s a real little pool of simplicity and aural beauty not without a touch of pathos.

Cast your Cornelius for true naive idealistic. A touch of worldly-wise “knowingness” and the role is ruined. He is wide-eyed and bedazzled by woman and love. …

And even more so his young companion: I hope you have an engaging young irrepressible.

Tell Dolly to advance on her monologue in Act IV with a meditative pause … The room empties; she alone on the sopha … change of mood … lost in thought, her eyes on the ground … collects the audience’s attention for her first words.

Please give my THANKS to all the players and to the Technical Staff (who so seldom get thanked) and my cordial best wishes for a happy preparation and a happy issue. Tell them the way to combat nervousness before entering on the scene is to stand at the entrance and breathe evenly and serenely—not too deep—but smilingly. Acting’s fun when the body is completely relaxed.

NOW I have almost no space left to wish you all a happy holiday. I sent on a little momento through the postal authorities today; I hope it gets through all right—it has to go through some kind of red tape in New York. … SPERIAMO as they say in Caserta. ¶ A world of affection to you Eileen; this letter has been taken up disproportionately with the strains and stresses of Show Biz. ¶ I wish I could SEE Julian. Is he in his last year at Eton? (All Americans believe firmly that there is a great deal of cruelty at Eton—I hope that’s no longer true!) ¶ And to you Roland

lots of old old friendship Ever Thornton

757 12th St. Douglas, Arizona

On or about Dec 11. 1962

Dear Catherine:

The Indians here used to communicate with one another over a distance by puffs of smoke; and that’s what my letters are reduced to. As the months go by I have less and less to recount, but more and more in the way of affection and regard to express. I don’t miss the centers of civilization, but I do miss the occasion to express affection and regard. Lord knows, one of the principal reasons I fled civilization was that I had to pretend such occasions so wearisomely often (all Americans play-act a social ecstacy—I more than others); now “society” is taking its revenge on me. Please accept the smoke and the bonfire under it; it says in papago language: bonjour chère Catherine.

It will require all your charity to understand me when I say that though I would be entranced to call on you this evening, and though it was always a happiness to come to dinner in East Rock Road,—an invitation to dinner with you tonight with the same friends would frighten me. I learned this on Thanksgiving Night at the seaport of Guaymas in Mexico. A friend had asked me to her house for the “rest of the turkey”; there were present two American couples, a Mexican couple and various children between 10 and 15. How quickly one becomes dishabituated. A dozen “personalities” in the room; two and three conversations going on; a distraction of lighting cigarettes and moving chairs and passing dishes and remembering names and being asked questions in non-sequitur.

And it can’t be denied that people wear a different face when there are more than three in a room.

When you live in isolation, as I do, you read more attentively. I pick up paperback novels in bus-stations. Ordeal of Richard Feverel62—doesn’t hold up. Return of the Native—doesn’t hold up. Jane Austen: incomparable. How seldom readers seem to remark on all that contempt for the whole human scene that lies just under the surface,—oh, more than that: a desespoir contenu, une rage déguisée63….. but by her art her spirit has been saved from mere spinster’s waspishness and from cholor. In Moliere the same contempt became aggressive. A man of religious mind believes the human race is correctable. There is not a hope of that in these two. Jane Austen’s only resource and consolation is the pleasure of the mind in observing absurdities.

¶ Word from Italy has given me great pleasure. In Milan the director staging the Assisi play found that actor after actor turned down the rôle of St. Francis—as blasphemous? non-canonical?—finally he engaged one of the finest of all Italian actors, Renzo Ricci (and his distinguished wife Anna Magni)64 and report is that all three plays are a great success. I did not express aloud my disappointment at the playing in New York or my chagrin at the spiritless reception. … all a dramatist can do is to murmur: “Some day. ….”

¶ The other day in Tucson I looked up an old Yale friend Jack Speiden, Yale ’22, in the hope he was still running his dude ranch where I might go for a few days around Christmas and imbibe martinis in front of a great log fire. Well, he’s retired; his wife is a grievous invalid with three nurses around the clock—a fall from a horse. Jack tried to persuade me to stay and dine with them Wednesday with the Paul Chavadjadzies—you know the spelling—I presume the parents of Bill’s friend. But I returned to Douglas.

Instead I am driving I think to Taos. Mabel and Tony are no more.65 Mabel rests and others are given a measure of rest. But I shall take Dorothy Brett out to dinner and ask her again of those old days—young D. H. Lawrence, Bertie Russell, Lady Ottoline, Katherine Mansfield … and about Mabel. It will be cold—it’s about 8,000 feet high—I hope I have cold’s compensation,—the beauty of snow.

Today (the 15th) I bought myself a Christmas present: a record player. I have three records, The Bach Magnificat; the Lotte Lehmann Lieder Recital; and the Mozart Sinfonia Concertante (Heifetz and Primrose).

From Tucson I sent a little <“>something for your breakfast tray,” just a pensee,66 a puff of smoke but laden. To all, all the Coffins and the-in-laws much affection

devotedly

Thornton

757 12th St. Douglas Arizona

Dec 19 1962

Dear Tappie:

So you’re a New Yorker.67

A New Yorker is like nothing else in the world.

I was once one, for about three months.68 I took an apartment in Irving Place. Morning after morning I’d get up at dawn, or before, and walk to the Battery, each day by a different route—through Chinatown, Polish Town, Italian Greenwich Village, the Jewish acres around Grand Street. At the Battery I’d feel myself nearer Europe toward which I suppose I strained.

The sense of the multitude of human souls affects every man in a different way. It renders some cynical; it frightens many; it made Wordsworth sad; me it exhilarates. I must go back and submerge myself in it from time to time or I go spiritually sluggish. What I have fled to the desert from is not the multitude but the coterie.

The sense of the multitude of souls is not the same thing as that of the diversity of souls—Shakespeare is the writer of their diversity: an island-dweller could not apprehend the millions of millions. The Old Testament is the work most freighted with realization of generations and generations.

As a New Yorker open your imagination to it.

I was delighted to hear from your mother on the telephone that you’re finding your classes absorbing: getting a good professor is a matter of sheer luck. In Oberlin I had one; in Yale I had none (but I had Tinker, though I was not registered in his course.) To be sure, I was not an assiduous student but any born teacher could have caught me—as Baitsell almost did in Biology and Lull in Geology—mighty remote from my daily preoccupations. (But they have left their mark in a tireless curiosity about science.)69

A little Christmas present has fallen to me in my literary life. That short play about St. Francis had a cool reception in New York. Divers friends and unshakeable judges let me know that I had not really finished it, or thought it through, that it was not thoroughly cooked. And I—o so deferentially—agreed with them. But something inside of me said: “Wait, just wait.” The three plays have just gone on in Milan. At first I was told that the director could find no actor who would consent to play Il Poverello. Did the role seem blasphemous or tasteless? or merely a colorless acting part? Finally the manager offered the play to a couple who are among the foremost in Italy, and the whole program is now a sensational success. MORAL: Pay no attention to the weather.

Now, Tappie, if you have to do an extended paper for one of your professors, and if you have to type it with carbon copies—please lend me one copy for one week. I not only want to read it because it’s yours, but because I want to see the kind of material and approach that the school expects, and because, as your father knows, I have a wide-ranging appetite to read anything in the field of humanities (except Old Goodenough on Josephus and T.S. Eliot on the theory of college education70).

I hope you take some exercise. Do you go to a gym? I hope you take some girls out dancing. And I hope that 1963 is your best year yet.

Lots of love

Uncle Thornton

P.O. Box 144 Douglas Arizona

Jan 11. 1963

Dear Thew:

Oh, I’m a skunk.

I meant to write you at once when I heard you were in the hospital.

I guess—from my proximity to Mexico—I’m catching the mañanas; I know I am.

Have you been a difficult patient? Throwing dishes at the wall, and turning up the TV full blast?

It must have been interesting having that other veteran of the Pacific Islands there; because you never talk about your war experiences. Does he, Kit?71 (And I go around ranting and raving about how I saved Europe—)

It turns out here that I’m not a 100% hermit. Once a month I have to go away. Usually to three or four days in TUCSON. But just as I went to Guaymas in Mexico over Thanksgiving to see the SEA, so I went to Santa Fe and Taos over Christmas to see the SNOW—and how I got it. My toes and ears darn near fell off. After 8 months here I’m a softie.

But I like it here completely.

I now have a considerable acquaintance but they are <the> type of persons that closes the bars. They say that Douglas and our sister-city Bisbee have the highest no. of churches per. cap. in the whole country. (It sure looks it.) But those exemplary citizens are safe in bed before I start going into society.

Tallulah is playing in Phoenix this week and I was half tempted to go up and sit up til four in the morning hearing four-letter words; but no! I’ve put all that kind of interest-curiosity behind. I’ve ’ad actors, I’ve really ’ad em.

I’ve been very pleased that the one-acters are getting a good reception in Milan—especially the Assisi one that left people cold in N.Y. They go on in Munich this month.

La Gordon writes that Gower Champion says that the plans for the musical Matchmaker are coming along great. Ruthie has been taking singing lessons (she told her teacher that she didn’t want to sing half-talk half-sing like most actors do; no, she wanted to learn to sing LOUD, and she says she is singing LOUD.) Didn’t I read that the role was being designed for Ethel Merman? (There’s LOUD, for you.) Anyway Ruthie feels she has a lien on that role for life.72

When your knee’s better I suppose you’ll be going down with Kit (choose the baby-sitter wisely) to see Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Ed. Albee has been telling interviewers that a conversation with me long ago made him turn playwright. If so I’m very proud. He sent me a copy of the text. Gee whillikers. Steel yourself. Its a blockbuster; but I admire it enormously.73 And isn’t it fine to have a new dramatist who speaks in his own voice?

Tell Kit that a score of expectant mothers have taken my advice: gaze at drawings by Raphael; listen to music by Mozart; float through the Parthenon and stroll about the Taj Mahal. Honest,—they’ve written me about it afterwards.

Get well serenely, you too<two?>.

To you both all best

from your old

friend Thornt

P.O. Box 144 Douglas Arizona

Jan 14. 1963

Dear Kays:

I’ve been here 7 months.

x

It AGREES with me.

x

But le petit train-train74 of my life makes me a poor letter-writer.

x

Tallulah and Estelle W. are playing Tucson at the end of the week in HERE TODAY.75

x

I’m half tempted to go up and sit with them until four in the morning. But I’d better not. That’s a different world. I’m not ready to reopen that door yet.

x

Judith comes soon. Macbeth-scenes and Medea.76

x

And Celeste Holm. Road shows are reviving. Some agent sends them out, starting in L.A.

x

I enclose a glimpse of my activities. Note: I don’t see a soul until long after sunset.

x

I found the last surviving honest garage mechanic and now my car goes like a dream.

x

I love hearing from you, but gee I have nothing to recount in return.

Love and kisses

Thornt’

SOCIETY NOTES

by our Douglas correspondent

A shower was given for RUSTY (barman at the Tophat) and his bride, at MIKE’s on Route 80 in Silver Springs. Beer, dancing, and clandestine gambling were enjoyed by over 90 guests. …. Among the presents were…..a can of Crosse and Blackwell’s kippered herrings and a can of coffee for percolating, from the Professor.

x

On Saturday night Louie (engineer) and Pete (highway patrol) and the Professor crossed into Mexico and had dinner and danced and smooched at the Copa. They then went on to visit a house of ill-fame, where the Professor’s Spanish was much in demand. All of the gentlemen returned to their homes at four in the morning, their virtue intact, but leaving most tender regrets with the beautiful young ladies.

x

Vera R., waitress at the Palm Grove, has gone to the Douglas Hospital for an operation. Among her callers was the Professor, who was not admitted to see the patient, but whose flowers were much appreciated.

x

The usual Stein Night (second Fridays) was observed at the Crystal Palace Saloon in Tombstone. Beer and tacos were much enjoyed by 85 guests. The beautiful “Duffie” (Miss Duffield) behind the bar was pleased to welcome her shy admirer, the Professor.

x

Mr. J. L. whose travels for electronic gadgets bring him frequently to Douglas received the help of the Professor in writing a letter to council and judge requesting that his alimony be reduced. Mr. J. L. hasn’t a bean; he lives in a trailer while his wife and two sons enjoy his six-room house. The Professor believes Mr. J. L. to the effect that he had never offended his wife in any way. She and another woman concocted a story about how he had struck her cruelly on six different occasions. Tie that!

x

Mrs A … B … a winter guest at the Hotel Gadsden again closed the bar (“one o’clock, ladies and gentlemen, thank you”) in deep conversation with her friend the Professor. There are now not many chapters in Mrs B’s life which have not been imparted to her attentive friend.

x

Dawson’s on the Lordsburg road is becoming more and more a place of entertainment for our Young Married set. Miss Winnie Shaw—former waitress at the Gadsden<,> now cook at her brother’s Hamburgateria—laughingly persuaded the Professor to dance with her. The crowded floor was soon cleared as the other dancers stood against the wall and watched the charming couple with admiration. Miss Shaw was told by her parents that she was related to the English dramatist George Bernard Shaw, which in view of her lively ripostes is not hard to believe.

x

P.O. Box 144 Douglas Arizona

Feb 7. 1963

Dear Catherine:

Many thanks for the records. I’m perfectly delighted with them both—the Mozart Quartets and the Landowska. My collection is still so small that each of them has its own particular invitation; I have the feeling that I’d lose that pleasure in them if I had, as some of my friends have, a whole wall of them.

I suppose Isabel may have told you that the New York representative of Ricordi—music publisher of Verdi, Puccini etc—has entered into a 5-year agreement with Louise Talma to promote The Alcestiad. Schirmers has just published her Etudes. She’s playing her new Passacaglia and Fugue next week at a concert in honor of Aaron Copeland at the Gardner Museum in Boston and the new Violin Sonata somewhere else and other performances are cracking on radio and in concert halls. I’m a good picker.

The Hindemiths were thrown into a consternation that I didn’t fly to Europe to hear the first of The Long Christmas Dinner in Mannheim or the second in Rome and now that I’m not flying to New York.77 Well, I’ve never attended the premières of my own plays. Shucks, it’s the public that’s on trial, not the authors. Hindemith’s opera is a jewel; it will appear everywhere; I shall be catching its 500th performance somewhere.

“How vainly men themselves amaze To win the Palm, or Oke, or Bayes; And their uncessant Labours see…”78

That’s the hermit’s beads. “Shouts in the distance.” I’ve just got a letter from Jerry Kilty. The Moscow Ministry of Culture has approved the dramatized Ides of March. It has been accepted for production in Warsaw; Turino-Milano-Roma October to December; London (with John Gielgud) in June. Paris in October.79 I presume it’s the same text that had a bad reception in Berlin. I wrote some new scenes for it; then my will-power broke down. It’s tedious work to rewarm yesterday’s porridge; and one can put no heart into putting patch-patch-patch on to a framework that was never designed as theatre. Had I intended to write a play on that lofty subject I would have gone about it differently in every detail.

x

I hope the worst of your winter is over—the famous winter of 19621963. Here, again erratic, we have plunged into full spring. We are in the 80’s by noon. Oh, how wonderful the sun is—and the moon no less so these nights. I now have quite an acquaintance in town, through I still havent been in a single home. There’s a Judge Hanson, 75—still on the city bench, who was born in Denmark. An omniverous reader and in small small way (he was director of the YMCA here and in Texas for years) a collector of pictures. Years ago in a second hand store he picked up a portrait of Walt Whitman (it was in Philadelphia) which he thinks is by Thomas Eakins. He’s consulted some experts and has a pile of documents but as yet no full assurance. If it is an Eakins of Whitman, think of what value it would have in the national interest. I’m to see it this week for my expertise! Often when the bars close at one we rakes cross over into Mexico where they don’t close if there’s still one customer sitting up straight,—Louie, the town engineer, Eddie, the Federal A.A representative at the airport; Rosie the elevator girl at the Gadsden; Gladys (great company) the cook at the Palm Grove and her sister Mrs Hert, an attorney. Well, well,—I’m the oldest by 30 years but nothing tells me so. The ladies drink margaritas, a tequila daiqueri that<’s> sipped from a champagne glass the rim of which has been dipped in salt. My best friend is Harry Ames who’s been going through a terrible time—the chicanery and general bitchiness of his father’s partner’s widow has ousted him from his Round-UP bar and liquor store,—a long Balzacian story. Harry’s wife Nanette has been crying for weeks. Harry will land on his feet, though. Harry and Nanette are college graduates—all of the above-named are except Rosie and Gladys,—but that doesn’t mean, ahem, that the conversation turns on T. S. Eliot and Boulez.

Well, I’m going to play myself KÖCHEL 46580 which I shall henceforward identify with you,—except that I don’t want to associate you with any of those passages of “glimpsed unfathomable dejection,” wonderful though they are. Give my love to all in Bill’s house and to Massachusetts and Long Island.81

your devoted cavaliere servante

Thornt’

P.O. Box 144 Douglas Arizona

March 17. 1963

Dear Isa:

Well, the opera thing is over.82 I know I would have found it very hard to live through. The easy thing about the Frankfurt occasion83 was that it was a beautiful professional performance. It’s as hard to be complimented as to be blamed for a performance when you know that some one or more elements in it (the recent Mr Antrobuses, or the actor playing St. Francis) absolutely deform the work. I’m tranquil about blame or praise if the work was adequately represented. Otherwise your lips are sealed; you’re not allowed <to> utter a judgment on your team-mates.

Heigh-ho.

I wrote those people who wanted me to find an agent for the Nebraska play, and the inquiry about the long poem translated from the German—I got out of them both prettily. I signed the book for publisher of the Penguins. N.B. The last line of The Matchmaker is six words short there, too.

I had a dinner party last night. Harry Ames who has lost his bar the ROUND-UP, has no job; and his wife and mother. His father was what in Brooklyn would be a saloon-keeper but here in the West was a sort of city father, the most admired man in town, a hand in politics, friend of all the governors and senators—even of Isabella Greenway.84 And his widow has the carriage and taste in dress of the best <of> St Ronan Street.85 Harry’s wife Nannette, very pretty, though she has been crying for weeks, Scandinavian, physical culture teacher until her baby came a year ago,—all very nice people and it never occurs to them to read a book. Cocktails, first in Apartment 6: I put Karkana cheddar and white fish roe on little crackers; and New York State champagne cocktails. After the first bewilderment they accept the fact that the Professor doesn’t go into homes.

Well. I won’t stew about any longer but come right out with it that I’ve written what must be 90 pages or more of a novel.86 I can’t describe it except by suggesting that it’s as though Little Women were being mulled over by Dostoievsky<.> It takes place in a mining town in southern Illinois (“Anthracite”) around 1902. And there’s Hoboken … and Tia Bates of Araquipa, Peru, transferred to Chile87…… and theres the opera-singer Clare Dux (Swift)88 …and Holy Rollers….. and how a Great Love causes havoc (the motto of the book could be “nothing too much”) and how gifts descend in family lines, making for good, making for ill, and demanding victims. You’ll be astonished at how much I know about how a family, reduced and ostracized, runs a boarding house. But mostly its about familial ties, and oh, you’ll need a handkerchief as big as a patchwork quilt. The action jumps about in time, though not as schematically as in The Ides. The form is just original enough to seem fresh; its not really like usual novels.

This morning I was doing a passage (Sophia’s nightmare) and was so shaken that I couldn’t go. I’ve had a headache ever since.—It’s terrible, the book!

All this since Christmas. I didn’t venture to mention it earlier because project after project has wilted away. But I’m darn well certain now that this is here to stay. I think it was the record-player that set things in motion, some Mozart and some organ works of Bach. Nothing I’ve written has advanced so fast, but it doesn’t worry me. Between the lines there’s lots of “Wilders”.

To think that that stroll that you and I took about Hoboken should have made such an impression on me! I must find out what kind of trees those were—lindens?

There’s melodrama in it, too, and a trial for murder.

So that’s the secret.

And you can imagine how my mode of life here now suits me.

I’m distraught on the two days of the week when I have to get out because the cleaning woman comes; I could eat glass with rage because I’ve mislaid my reading glasses; I postpone the boring necessity of taking my drivers test. I’m only ready for interruptions after sunset. I don’t work at night—twice it led to two sleepless nights—I, who never have any trouble sleeping. (You should read the account of Mrs. Ashly’s insomnia!)

Every new day is so exciting because I have no idea beforehand what will come out of the fountain-pen.

I hope Alice lives to read it; she has gently implored me to do a novel for a long time.89

love

Thornt

<appeared above the letterhead>

Last days at

Nov 18 1963

Dear Harold:

It puts me in a very funny position to have to repeat to kind well-wishers that I think The Alcestiad is not a workable play. It makes me look like someone fishing for more and more compliments.

I don’t mind having a failure but I hate to involve others in a failure.

Mr. Strasberg90 wrote me about the play, but (confidentially) his interpretation of the first two acts was miles from what I meant and his recommendation for the rewriting of the last act was unbelievable. That’s not his fault, but mine. As I wrote Cheryl91: it’s a pan of rolls that didn’t get cooked through in the oven.

It’s too bad.

The only way I can pull myself out of this awkward position is to do another so that these well-wishers can forget poor Alcestis

I’ve written Isabel that I’m not yet ready to return to urban civilization. I need one more year in some village, probably abroad. My new novel (not announced yet) is approaching its final draft. Then I’ll “go theatre” again.

I’m sorry to be leaving the desert. It’s done a lot for me.

But so will a change. Including (oh Lord!) a change of food. Can you imagine living a year and a half with almost never an attractive bit in<on> your plate?

But I’m well and cheerful and grateful to Arizona (the State where WATER is GOLD. You should hear the political thinking in the bars that I frequent! I was told the other night—in a fist-beating roar—that the late Mrs Roosevelt did more harm in the world than TEN Hitlers.) A woman working in the Douglas Telephone office asked an acquaintance “Who is that Mr. Wilder? Is he a communist?<”> Her thinking goes like this:

He makes $8 long-distance calls (once a week to Isabel, yet <).>

He makes $8 long-distance calls (once a week to Isabel, yet <).>

He doesn’t own a phone.

He doesn’t own a phone.

He makes them through the central office so that they can’t be traced.

He makes them through the central office so that they can’t be traced.

He has a funny accent and even in August he wears a necktie

He has a funny accent and even in August he wears a necktie

Q.E.D.

Please give my affectionate best to Sam and Elza.92 and love to Sam<,> May and Bobbie93

from

Thornt’

TNW receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson in the White House, December 6, 1963.

TNW receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Baines Johnson in the White House, December 6, 1963. Cecil Stoughton, courtesy of LBJ Library.

Dec 29 1963

Dear Tappie:

D’une elégance! D’une beauté94

And particularly welcome now—can you guess why?

Not only are they warm and comfortable, but they are of this elegance.

For the next few months, perhaps the whole year, I must live (as so often before) on boats and in hotels.

Nothing impresses the stewards on boats and the chambermaids in hotels like a luxurious pair of pyjamas to spread on the bed every night.

I’m sorry to say it, but there’s no snob like a servant. And I’m sorry to say it, but there’s no ill-clad down-at-heel bum like your uncle. So now you’ve given me a chance to hold up my head and get a little more considerate service. Thanks, many thanks.

x

As you are beginning to think about writing a novel, here are some suggestions that would be of use to some young writers—but every writer is different and they might not apply to you at all:

Don’t begin at the beginning. Begin at some situation near the middle of the work that is livest to your imagination.

Don’t begin at the beginning. Begin at some situation near the middle of the work that is livest to your imagination.

In fact, don’t begin a novel; begin a note-book toward a novel.

In fact, don’t begin a novel; begin a note-book toward a novel.

This notebook contains not only scenes and bits of conversation that may find their place in the novel; but make it a sort of journal wherein you talk to yourself about the novel (objectify your thoughts about it, by writing them down.)

This notebook contains not only scenes and bits of conversation that may find their place in the novel; but make it a sort of journal wherein you talk to yourself about the novel (objectify your thoughts about it, by writing them down.)

Lots of novelists waste time and “poetic” energy and courage (the most important ingredient of all) by not deciding early what kind of novel it is. In some novels the reader simply hears and sees what happens; in others he hears the author’s voice explaining and analyzing what’s going on. The two methods may be combined but must be evenly distributed. You can’t indicate for 30 pages that you know all about Jim and Nelly and then withdraw and merely exhibit Jim and Nelly for the next 30.

Lots of novelists waste time and “poetic” energy and courage (the most important ingredient of all) by not deciding early what kind of novel it is. In some novels the reader simply hears and sees what happens; in others he hears the author’s voice explaining and analyzing what’s going on. The two methods may be combined but must be evenly distributed. You can’t indicate for 30 pages that you know all about Jim and Nelly and then withdraw and merely exhibit Jim and Nelly for the next 30.

You’re a Wilder. Fight against the didactic,—the didactic-direct.

You’re a Wilder. Fight against the didactic,—the didactic-direct.

When you are about one-third through your work, you will pass through a phase in which you despair of it, you loathe it, you loathe yourself, etc. Any work—a sonnet, a short story, or an epic poem. Always happens. Expect it. Be ready for it.

When you are about one-third through your work, you will pass through a phase in which you despair of it, you loathe it, you loathe yourself, etc. Any work—a sonnet, a short story, or an epic poem. Always happens. Expect it. Be ready for it.

The theme of a work should express some inner latent question in yourself. It is best when this is so deeply present that no one else would recognize it. Without this you will become bored with writing.