305. TO JOHN K. TIBBY, JR. ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Yale

<appeared above the letterhead>

P.O. 862 Edgartown, Mass. 02539

May 5 1967

Dear Jack:

Before I received your letter one arrived from Grace Foresman telling me of the divorce, of Emily’s and Bill’s interests. I’m glad to hear from you.

I hope for both of you that the new situation—since it had to be—is “working”, that you’re making a good thing of it.

I burst out laughing at your mention of p. 327 of my book. Old writing-hand though I am, it still comes as a surprise (even a shock) to me that readers find anything “usable” in my ruminations. I am so little of a dogmatic type that my first impulse is to exclaim “Oh, I didn’t mean to be taken as seriously at that,—I was just kicking the subject around.”

My sister Isabel will forward the Life-Time Tributes to Harry Luce soon. I just received a reply from Mrs Luce (Tempe, Arizona). She thought I was still living the “hermit” in Arizona and wished I would come up and spend a day with her: she wanted to learn about those early years of Harry that she had never understood. (Incidentally, she described herself to my sister as very lonesome.)128

Harry Luce, Bob Hutchins, my brother Amos and I (all near classmates in New Haven) are a very special breed of cats. Our fathers were very religious, very dogmatic Patriarchs. They preached and talked cant from morning til night—not because they were hypocritical but because they knew no other language. They were forceful men. They thought they were “spiritual”—damn it, they should have been in industry. They had no insight into the lives of others—least of all their families. They had an Old Testament view (sentimentalized around the edges) of what a WIFE, DAUGHTER, SON, CITIZEN should be. We’re the product of those (finally bewildered and unhappy) Worthies. In Harry it took the shape of a shy joyless power-drive. And like so many he intermittently longed to be loved, enjoyed, laughed with. But he didn’t understand give-and-take. Bob and Amos and I—bottom of p. 148!

I wish you’d known Brit Hadden.129

I wonder what school you’ll select for Bill. Largely approve of your avoiding the big ones—but such decisions are closely related to the nature of the student.

Martha’s Vineyard is my hideaway now—until the “summer people” come. Bad weather, seagulls and I.

If you feel like it some rainy Sunday afternoon open a beer and write me. (God, you typewrite elegantly.) Oh, I forgot, on Sunday afternoon you’re on your boat,—well, Sunday night. Where were you born? Where did you school?—Are you making most of your own meals, like me? Since the divorce are you more of a convivial or less? Do you do a lot of reading? What are you reading?

Your loyal

Uncle Thornton

P.S. I gathered, between the lines, that Grace admires you very much. TNW.

306. TO WILLIAM I. NICHOLS. ALS 4 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) LofC

<appeared above the letterhead>

Passing through N.Y. to see my sister Charlotte in the sanatorium on Long Island

Friday

<August 1967>

Dear Bill:

Many thanks for sending me your “talk.”

The larger part of it is finely organized and phrased.

I think it’s a very important movement (for good or ill) and not likely to be drowned out by civil rights riots.

I think you can very much count on its CONTINUING to change it<s> form:

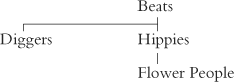

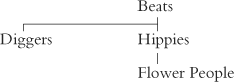

The Beats were vagrant (few women; you can’t wander about with women); picked up occasional jobs (no begging) and little said about “smoking”, etc. Lots of poetry-readings; quasi-religious via the Orient.

x

Hippies—sedentary community. Totally drug-oriented. Hence—as you point out—the atrophy of the “will”. Debasement into panhandling and begging (very un-American.) Debasement of the ideological rationales—don’t know anything about their Hindu chants or Zen disciplines. Omnipresence of women, but “pot” is very much a sex-substitute: “you pursue your beatitude; I’ll pursue mine.”

x

The Diggers: I wish I knew more about them (including the history of their name and their hats—a sect in England—deported as convicts to Australia—the altruistic mission of the sect survives all those vicissitudes and reappears in the Hippie movement.)

The Diggers show us all the admiral<admirable?> aspects of this Revolt of Youth; what it could have been, if it had not become devitalized and “fuzzied out” by pot.

x

The sad thing about youth is that it doesn’t know anything.

The admirable thing about youth is that it truly desires to live correctly and to use sincerity—not convention—as the criticism of the “correct.”

After the First World War German youth broke away from the German home,—and what a “home” it was: “if Paul-Jurgen and Grete do their homework every night of the week they can go for a walk in the hills with Papa and Mama on Sunday!”

To the consternation of all decent-minded people, the youth left the house and wandered over the world. Literary influences, also: they sang mediaeval latin songs to the zither; a certain amount of shocking free-love also, but a strong askesis: they repudiated beer as identified with the “fat” generation that had lost the war. They were emancipated—free, vocal, happy in “nature” and intensely hopeful. The Wandervogel movement.

And Hitler seized all that promise and adopted it to his own purposes—just as “drugs” have betrayed this movement. Because the young don’t know anything.

Everybody blames the American home, but that’s only part of the injustice to the young.

There’s the school. The American School (and the German before it) have failed to render knowledge and the exercise of the mind attractive.

There’s a terrible line in an old play by Thomas Corneille—brother of the great Corneille: Combien de virtus vous me faîtes haïr130

The American home can’t help the young becomes<because> the parents, too, went to the American school.

Children love to learn. But they’re fed “canned facts”. The schools, outside the cities, look more and more like country clubs—which is all right—but English and History and Math still resemble punishments.

A revolt (and an understandable revolt) has been led into the wilderness by drugs.

But—as you say—it’s discovering its own dead-end and bankruptcy.

But the movement goes on. And new young people are reaching 17 every day and will repudiate this generation.

I’m eager to see what’s coming.

Damn it, I didn’t mean to run on like this.

But, Lord!—I’ve battered your poor ear off before.

Again thanks for your fine address.

My regards to Gnädige Frau.

Your old friend

Thornt.

307. TO JAMES LEO HERLIHY.131 ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed Norddeutscher Lloyd Bremen an Bord <TNW added “BREMEN” to the printed letterhead>) Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

<appeared above the letterhead>

until after Christmas at, or near, American Express Co. 11 rue Scribe, Paris.

Middle of the Atlantic

November 10 <1967>

Dear Mr. Herlihy:

Your letter gave me much pleasure

Forgive my being so long in answering. I was living all alone on Martha’s Vineyard. SUMMER people gone, most of the eating places and bars closed—just us natives and the seagulls.

I was enjoying a breakdown—not a nervous breakdown, or a mental one—just a breakdown of the will. Nothing tragic, nothing even pathetic—merely dreary and unmanly—very Russian,—but deeper than mere laziness and sloth.

So much for apology. I’ve shaken off the condition on shipboard.

I knew your name—and with lively esteem—but I couldn’t recall where I knew it. When suddenly I found in the local stationery shop a copy of ALL FALL DOWN. I’d never read it, but I remembered the movie well—not only for three striking performances132 but for an overall searching honesty in all that suffering and a rich illustration of the world in which those persons lived. I’d made a mental note to get hold of the book, but other things intervened.

Well, I read it and the pleasure I got from it multiplied the pleasure your letter gave me.

Yes, you and I are Middle Westerners.133 (I left my birthplace Madison Wisc. at the age of nine, but returned for two years at Oberlin—and then for six years teaching in Chicago.) But more than that we have a feeling about the Middle West’s non-prosperous middle class that is not often found. We don’t hate or mock it or sentimentalize it (Booth Tarkington) or condescend to it (Sinclair Lewis). It is, as it were, <“>romantic” for us: we rejoice in the whole gamut from farce to tragedy. (For my part, I’m including not only The Eighth Day but the “road” and the Kansas City of Heavens My Destination.) Gertrude Stein has a very fine passage about how every writer should have the country he lives in and knows and the country he—in no trivial sense—romant<ic>izes. For the Elizabethans she said it was Italy; she lived in Paris but she “dreamed” about America. This is true about strata of society, too. My first book The Cabala was about a very rich milieu in Rome that I knew nothing about. My New Hampshire village in Our Town is pure imagination: I tutored in summer camps and I was a guest at the MacDowell Colony. I seldom entered “homes.” I took late strolls and looked through windows. I lingered in stores and post offices. I looked and listened. I don’t know whether your Cleveland comes from a saturation of actual experience: for me it has the solidity and fascination of a partially imaginative reconstruction. Have you ever noticed that Farrell’s Chicago134—for all its millions of words (and his undoubted gifts)—has no real “psychic color” of the place?

But oh! that Seminary Street, and that Florida!

And Clinton’s suicide letter!135 And lots and lots of pages.

Belatedly

but with

plenty of

sincere thanks and regards

Thornton Wilder

I wish you could see your way to the theatre again,136 but the trouble with the theatre (now days) is that you’ve got not only to tell your story, but you’ve got to devise some novel element in the manner of telling it,—to innovate in form, damn it.

308. TO SCHUYLER CHAPIN.137 ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed Hotel Continental / 3, Rue de Castiglione / Paris) Yale

American Express Co. 11 rue Scribe Paris

Nov 29 1967

Dear Mr. Chapin:

Many thanks for your letter. I follow closely the work at the Vivian Beaumont Theater and am delighted that it has gained its stride and is doing fine things. All continued success to it.

The thing that prevents my wishing to see my play in the Lincoln Center might seem to many a small idiosyncratic difficulty, but to me it’s important.

That 30-year-old play has been done over and over again in school auditoriums, Sunday School halls, gymnasiums and theaters-in-the-round. I have seldom heard of its being performed in the theater for which it was intended: the conventional box-set stage with the brick wall at the back, the heating-system pipes, etc. I have always felt certain that a large part of the effectiveness of the original production came from the emergence of Grovers Corners—not from an abstract “non-place”, but from that homely even ugly “rehearsal stage”. (The same is true of “Seven<Six> Characters in Search of an Author.”)138 The audience’s imagination has to fight doubly hard to overcome and transcend those concrete facts.

I was confirmed in this conviction when I read the reviews (and received letters from friends and strangers) of William Ball’s revival last year in San Francisco.139 They were surprised that the play had such meat in it; they had seen it often (usually with relatives in the cast) and remembered it as pretty and pathetic and easily forgetable.

So when I—at the age of 70—was approached on the matter of a “serious” anniversary revival, I was filled with the hope that we could have either of the two theaters of the first run: the Henry Miller or the Morosco,—or certainly one like them. There’s poetry in Our Town—those crickets, the toot of the train’s whistle approaching Contookuk; but its not the same kind of poetry as in the dramas of the Elizabethan age and the Spanish Golden Age—which rejoices in an abstract scenery-less setting. My “poetry” rises from little homely objects; it must win its poetry from steampipes and back stage ladders.

[This is odd coming from me, who later went all out for the arena stage.]

Bill Schuman140 has also written me a friendly letter. I’ve told him that I’ve written you. Would you kindly let him see these paragraphs?

And all best wishes to the work you are doing.

Sincerely yours

Thornton Wilder

P.S. And Morton Gottlieb141 who, I think, didn’t get the point when I tried to explain it earlier.

TNW.

309. TO CASS CANFIELD. ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed Hotel / Colombia Excelsior / 16126 - Genova Italia) Yale

Friday March 1. 1968

Dear Cass:

Isabel’s phone call yesterday at dawn and her cable received this morning leave me in some doubt as to whether (“addressed to your home before Saturday noon”) you wish a mere statement of my acceptance of the prize or an extended portion of a 500-word speech of acceptance. I have sent you the cable of acceptance and I now send you a few notes to add to a short acknowledgement of my gratification—to be delivered, I believe, on March 5.142

Isabel said that you already had some fragments of a letter that I wrote you which you intended to draw upon.

x

Here are some additional jottings which you may or may not wish to incorporate.

x

The principal idea that is expressed in the novel (and in its title) has been present in Western thought for some time—that Man is not a final and arrested creation, but is evolving toward higher mental and spiritual faculties. The latest and boldest affirmation of this idea is to be found in the work of Père Teilhard de Chardin—to whom I am much indebted.

x

It has given me pleasure to be both commended and reproved for writing an “old-fashioned novel.” There is the convention of the omniscient narrator, reading his character’s thoughts and overhearing their most intimate conversations. I have been more reprehended than commended for introducing many short reflections or even “essays” into the story. That is old fashioned also, stemming from Henry Fielding. I did this even in my plays: there are little disquisitions on love and death and money in “Our Town” and “The Matchmaker.” I seem to be becoming worse with the years: the works of very young writers and very old writers tend to abound in these moralizing digressions.

It has somewhat surprised me that few readers have found enjoyment—or even noticed—the allusions, “symbols,” musical them<e>s that are a part of the structural organization. These cross-references are not there to tease or puzzle; they are not far-fetched or over-subtle. It is hoped that they reward and furnish both amusement and insight in a second reading of the book. It is a device particularly resorted to by writers in their later decades.

x

So, Cass—if there’s anything here that can save you time and trouble—use it—or just throw it away.

x

Again my thanks to the committee… deep appreciation, etc. …

The hermit of Arizona will be home soon—but even more hermitlike than before.

A world of regard to you, dear Cass—and to Beulah who may have to decypher these words

Ever

Thornton

310. TO TIMOTHY FINDLEY.143 ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) National Archives of Canada

April 20 1968

Dear Timothy:

Many congratulations. Thanks for your letter with the good news. Yes, indeed, Viking is <a> very fine publishing house.144

I’m glad you’re turning to write for the stage. I’m sure you’re endowed for it as well as experienced in it. Beware, however, of regarding yourself theatrically. You and your sense of guilt about Dr. King’s assassination! In a very general sense everyone is daily responsible for some measure of injustice and ill will in the world—but you taking that crime on your shoulders—it’s like putting on a penitent’s garb in amateur theatricals and admiring oneself as a “Great Sinner.” You rightly describe yourself as seeking “quiet”—well, don’t endanger your own quiet by introducing imagined troubles like that.

For this play:

Select your subject carefully. One very real and close to you—not autobiographically but inwardly. Take long walks—view it from all sides—test its strength—its suitability for the stage. Then start blocking out the main crises or stresses. I suggest (though all writers are different) that you don’t begin at the beginning but at some scene within the play that has already begun to “express itself in dialogue.” Don’t hurry. Don’t do too much a day. In my experience I’ve found that when I do a faithful unforced job of writing every day that the material for the next day’s writing moves into shape while I’m sleeping. Never hesitate to throw away a whole week’s good hard-won writing, if a better idea presents itself.

All cordial best wishes to you

your old friend

“T. N.”

311. TO CATHERINE COFFIN. ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Yale

April 22, <1968> some say

Dear Catherine:

This is one of the most heart-felt thank-you letters I ever wrote. I’m thanking you for pure intention. What could be more courtly?

Like some great lady of the Renaissance—a Borgia, a Medici, pupils of il grande Macchiavelli you extracted from me that I already owned the magistral recording by Fischer-Diskau<Dieskau> of Der Lied von der Erde.

A gift, an intention, à la hauteur145 of yourself and—I hope—of me.

So:

I thank you with the weight and expansiveness of my 72nd year.

x

Now I have a confession to make to you. When we saw you Thursday night I was all steamed up to tell you about my newly-acquired interest and concern about Professor Herbert Marcuse. It may be that you know more about him than I do. Besides, Thursday night I hadn’t my ideas fully organized and I was afraid that I’d make a foolish exposition of them.

My hotel in Genoa was on the same street as the main building of the University. Constant protest agitation. I passed it the day that the students sat—hundreds strong—in the mighty portals and on the vast staircases to prevent the Rector and his council from entering his office. I assume they were at the “back doors,<”> too.) Among their banners and placards were

and so the names were linked in Rome and Berlin. And Prof Marcuse was calmly giving Socratic interviews to pilgrims from all over the world in his office as Professor at the University of California in San Diego.

The first wide-spread revolt that has not been able to engage the cooperation or even sympathy of the laboring classes and the proletariat. He explains that.

In all ages a ruling hierarchy has exploited the slaves, the enfief-fés<?>.146 the industrial worker… and revolts have been about economic justice—ie money.

But now Capitalism has reached a new type of reducing men to servitude. The Technological Establishment makes sheep of men by making them “one-dimentional men”: by publicity means it tells them what they want and gives them what they have been taught to want. The industrial workers and the bourgeosie like their new condition. They’re seduced. <appeared perpendicularly in left margin beside previous three paragraphs> N.B. Marcuse is a Marxian but believes that Kremlin-Communism is doing exactly what Capitalism is.

The press (hence the students’ hatred in Germany of the magazine-lord Springer147) feed them irrelevant pap; the universities form technological robots and irrelevant “culture”; the governments “absorb” and trim the claws of socialist parties—

All is soothing de-individualizing—

Marcuse showed the young what to revolt against; and how to go about it—

Massive resistance—with or without violence.

What he proposes (now their aim) is a dictatorship (yes) of the intellectuals who see through the technological strategy: a dictatorship which once having produced the New Man will be superceded, will disappear into thin air.

So utopian dream fantasies—again.

In the meantime we have this really “massive resistance” against the technological stupifying of man.

Love—every day of the year

Thorntie

312. TO WILLIAM A. SWANBERG.148 ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Columbia

July 25. 1968

Dear Mr. Swanberg:

Please forgive this delay of my reply to your letter of July 10. I have recently returned from the hospital after a serious operation.149 I shall be out of circulation for some time.

Yes, I knew Harry Luce over many years. He was, for the most part, a shy and guarded man. I think it was the fact of our long association that made him particularly so with me. After college days I saw him seldom—always in large groups—once when he came to speak at the University of Chicago;—at the reunions of the Class of ‘20—I dined with the Luces twice in the Waldorf Towers. About 10 years ago Harry invited me to a meeting at the Chinese Inst<it>ute (if I remember the name of the institute correctly) to honor the recently dead Dr. Hu Shih.150 He gave me no intimation that I was to be called on to speak. I went to this meeting in New York merely to express my regard for Harry. (I have never been sympathetic to the non-recognition of the People’s Republic of China.) To my surprise I discovered that I had been assigned the rôle of concluding speaker on the program. I heard Harry introduce me as an old friend of Dr. Huh Shih. I spoke—to the best of my knowledge—of Dr. Huh Shih’s work as a scholar and reformer of the Chinese language. I did not tell the audience (nor Harry until the close of the meeting) that I had never met Dr. Huh Shih.

I liked and admired much in Harry. I believe (with Charles Lamb) that “one should keep one’s friendships in repair”; but that takes two.

I shall be here a number of weeks under house arrest. If you wish to mail me the photo from the China Inland Boys’ School I shall endeavor to identify Harry; but I am still too tired to receive any callers except relatives and old friends.

All best wishes toward your task.

Sincerely yours

Thornton Wilder

313. TO E. MARTIN BROWNE.151 ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Harvard

July 30 1968

Dear Friends:

Absolutely delighted. Couldn’t be in better hands.

Oh, how I hope it finds friends among you all.

There’s usually an air of suppressed excitement about rehearsals—because its a large cast with so many “distinct” parts in it; and because the actor begins to feel an additional responsibility on him because there is no scenery.

If I’m not mistaken Martin—the kindest of men—will discover that he has to be as “mean” and tyrannical as a lion-tamer or as a Toscanini. Actors—by selection and training—are highly suggestible; they will try to impose the mood (not the content) of the last act on the first two. They will “grave-yard” the whole play. (Oh, the productions I’ve seen; this applies to The Long Christmas Dinner, too.) For two acts nobody has the faintest notion that they will die or even that time is passing (except the Stage Manager and he only indicates that he is aware of it by an increasing dryness of tone); and even in the third act the mood is not elegiac: it mounts to a praise of life that is not impassioned regret but insight—and affirmative insight. The poignance is not on the stage but in the hearts of the onlookers.

I love those moments when the actors are real loud—milkman with his horse; Emily and her school friends. We found that the biggest laughs in the play (and legitimate laughs) are when George decends to breakfast.

“Four more hours to live”—noise, real loud, of cutting his throat.

Breakfast with Mr. Webb. Long embarrassed pauses and glances while stirring their coffee, then MR WEBB—real loud!—“Well, George, how are you?” George almost loses his mouthful.

God grant you can find an actress who can say Emily’s farewell to the world not as “wild regret” but as love and discovery.

[Did you recognize that that speech is stolen from the Odyssey—Achilles in the underworld remembers “sleeping<?> and wine and fresh raiment”!!]

N.B. It was GBS who said “Every child born into the world… etc”

I’ll be interested to know if an English audience finds Emily’s self-satisfactions (about being “wonderful” in her class studies) unappealing.

NB One Mrs Webb in ten is able to remain apparently unresponsive to Emily’s appeal to her in Act III

I love dear Henzie152 as Mrs Soames—real loud, her voice cutting across the wedding—the village gossip, etc. Fun.

I’ll send a cable

lots of love to you both

Thorny—

P.S. Had an operation July 2—hernia—am still under house-arrest—progressing fine—Isabel taking wonderful care of me. She sends her love, too.

TNW.

314. TO RICHARD GOLDSTONE. ALS 3 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) NYU

Nov. 19, 1968

Dear Richard:

This is going to be an unpleasing letter for you to read So sit down and reach for a cigarette.

x

I’ve been telling you for years that I’m not the kind of author that you understand—that you should treat. I’m not tearful, I’m not self-pitying, I don’t view myself tragically, I don’t spend any time complaining or even looking backward. I’m energetic, full of projects for the future, engrossed in other people’s writing (Lope de Vega, Joyce), engrossed in what happens about me.

x

In July a week after my operation you wrote me a letter that contained some phrases that were so absurd, so obtuse, so lacrimose wrong-headed that I burst out laughing and then got mad. Damn it, you wrote:

“and each year I understand you better. I understand that your life has been difficult, filled with profound disappointments, with strivings and struggles, that the rewards have not been many.”

Where the hell do you get that?

You get that out of your own damp self-dramatizing nature.

God damn it, I’ve lived a long life with very little ill health or pain [in the same letter you talk of the “great pain and discomfort. … all the agony” of my operation. Go fly a kite—it was amazingly free of discomfort; it was bracing; I wouldn’t have missed it… you derive some dreary relish in draping other people with fake misery]. Struggles? Disappointments? Just out of college I got a good job at Lawrenceville and enjoyed it. I made a resounding success with my second book. The years at Chicago were among the happiest in my life. I got a Pulitzer Prize with my first play.153 What friendships—Bob Hutchins, Sibyl Colefax (400 letters) Gertrude Stein, Ruth Gordon (hundreds of joyous letters, right up to this week).

What’s the matter with you?

x

Of course my work is foreign to you.

You can’t see or feel the play of irony.

You have no faculty for digesting serious matters when treated with that wide range that humor confers.

For you the woeful is “mature”—you chose the Pariah as a thesis-subject154—the solemn-humorless alone is “grand.”

Go pick on Dreiser or Faulkner. Leave me alone. Write about Arthur Miller.

x

Also you’ve never understood—though I’ve warned you—that I am not interested in my past work. I refused to cooperate with those authors who put out books about it—poor Isabel had to bear the burden.

I can’t help feeling that you so far misunderstand me that you think I’m flattered when you run up palliatory extenuating phrases about The Trumpet Shall Sound or The Marriage of Zabett (I can’t remember a word of it—not even “the yellow lakes”).155 I suspect that every self-respecting author loathes hearing his juvenilia mentioned. stop it.

x

In Gertrude Stein’s Portrait of me she says:

“He has no fears.

At most he has no tears.

For them most likely he is made of them.”156

“For them” means for a large part of the reading public—and for you—The Bridge of San Luis Rey and Our Town are tender, tear-drenched, and consoling. But they aren’t, they’re hard and even grimly challenging, for “he has no fears.” Stop wringing your hands over me and find your own congenial subject.

x

I’m leaving a copy of your letter of July 10th and this letter with my literary executor

x

I’m sorry I’ve had to write this letter, but at 71-plus I must speak to you with absolute firmness (you have a way of not grasping what I’ve said a number of times) and I must clear my decks.

Sincerely yours

Thornton

315. TO CATHARINE DIX WILDER. ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Yale

Nov 19. 1968

Dear Dixie:

Loved your letter.

Rê Mexico.157

I never got much relish out of Mexico City. Maybe the altitude leaves you with a faint malaise (don’t move fast, or touch alcohol the first 24 hours.) Mostly because the young ambitious republic tried to build its capital in imitation of Paris of the Exposition style.

But the Mexico of the villages and smaller towns is a warm glowing mysterious proud and gracious thing—largely derived from the survival of Indian blood in the people (they are descendants of great civilizations, too.) The Spanish civilization was a great one, but its descendants in the new world exhibit too much and in adulterated form the old world characteristics—vanity, pompousness, insecure and easily injured pride, obstinacy, “closed minds.”

Try to see something of the villages, especially on their market days. Note the eyes of Indians—obsidian black, but so watchful (not primarily distrustfully, but humanly) and so quick to catch a courteous or friendly overture. You have a tendency to be “little princess” shy and stand-offish—oh, don’t be so with the Mexicans or you’ll come to hate Mexico—catch the eye of every waiter and waitress, of every sales-girl, and watch the result; abound in muchas gracias and buenos dias, buenos tardes.

Even American tourists—they’re crazy to talk to other Americans. Give them the outgoing warmth, too. You may find some tedious sides of the hosiery manufacturers from St. Louis—but you’re a beautiful young woman. Get to know them: you can brighten their voyage.

x

Mural painting is one of the greatest of all art-forms. It’s dead in Europe and in Boston (Sargent and Abbey and Puvis de Chavannes—in the Library—dead.). But it came to life in Mexico (from the Indian blood—how to cover a wall—)<.> We now know the once-fashionable Rivera was merely a gaudy illustrator; but Siqueiros and especially Orozco are magnificent.

x

The great betrayal, the Tragedy of Montezuma—

x

The charm and felicity of the folk-arts,—taste. Taste always resumes centuries of high culture—that the Mexican Indians have.

x

Maybe you’ll have time to read D. H. Lawrence’s The Plumed Serpent—a lot of it is downright silly, Lawrence’s Messianic complex—but the description of Mexico City at the beginning and of the village life on the lake later—is masterful.

x

There are hundreds of travel books, mostly ephemeral. A good travel book doesnt date: Flandreau’s Viva Mexico158 is still as telling as though it were written this morning.

x

A trip to a foreign country can also be a renewal of oneself. Go to Mexico as a new Dixie. Be audacious, daring, fun-loving, vulgar, “Mexican”—I send you my CHRISTMAS PRESENT in advance—have (create) the hell of a time. I sail for Europe next Monday (Isabel follows me soon to Paris and Switzerland) but wherever you are you are my treasured niece

sez with love

Old Uncle Thornton

316. TO JAMES LEO HERLIHY. ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed Post Office Box 862 / Edgartown, Massachusetts 02539) Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

<appeared above the letterhead>

Last day at

(Martha’s Vineyard.) until after Labor Day. But my sister will be here and will be forwarding mail.

July 25 <1969>

Dear Herlihy

Selah!

Here’s the dope you asked about:

I got fed up with academic and cultured society. (As I put it: “if one more person asks me what I think of T.S. Eliot, I’ll shoot<”>). May 1962.

I decided to go to the desert and be a hermit. From the map I picked out Patagonia, Arizona. (As children we didn’t say “Go to Hell!” but “Go to Patagonia!”<)> I drove across the country for the sixth time—love the Road, the gas stations, the motels—the fried egg sandwich joints.

My car began to stagger and poop out as I came to a hill and a sign saying WELCOME TO ARIZONA. I just managed to get to the bottom of the hill: DOUGLAS, ARIZONA. 1 ½ miles from the Mexican border. I stayed there 20 months. No phone. Made my own breakfast and lunch. Closed* the local bar (midnight in that State.). 5,000 people—¾ of them Mexicans come over the border to put their children in our schools. A once pretentious hotel for T.B’s and asthmatics and arthritics—on its last legs, breaking up. A few small ranchers. Local airport staff. Bar “help”, restaurant “help.” (There was a bit of “society” there; engineers at a smelting works, with a country club, etc. but I never went into their homes and was never asked.) There was a vague notion that I “wrote”, but whether it was phony Westerns or books for children no one gave a damn. Once a week I drove 60 miles to Tombstone for dinner or Nogales; once a month to Tucson or Phoenix. Some casual and agreeable friends—no attachments, no claims or demands either way. JUST WHAT I NEEDED. Took me three months to blow the cobwebs of self-conscious genteeldom out of my head. Then I started the novel (I thought it would be a short novella.) A record player—I worked under the clouds of Bach motets and Mozarts last string quintets—just about the tops of all music.

So after 20 months I left, reluctantly, but I knew that inevitably the blessing of change that it offered would in time cease to be change.

Ever since I keep hunting for another “Douglas.” Nearest to it are SPAS out-of-season. (I’ve never stayed here so late before but the give-and-take of hospitality is beginning to overwhelm any idea of work: all pleasant people: Lillian Hellman, the Feiffers, Mia Farrow,—like that.<)> I return in Sept, Oct—nobody here but the chowder-makers, the sea gulls and me. … St. Moritz out-of-season—Saratoga Springs out of season.

No, I didn’t say the couch was the writer’s enemy but I quoted George Moore: the writer must resist the writer’s temptation—the desire to go out and find someone to talk with. Desultory conversation—gassing—is the enemy.

We have a hippy population on this island. But ours are “well-to-do” ones. It costs $5.50 to get on and off the island by ferry. The Police cracked down on them last week and jailed a dozen or more (there had been an FBI informer among them for months); they put their finger on the pushers. We have also a stratum of drop-outs—girls “waiting” in the bars and restaurants—very nice some of them. And men who talk your ears off about how they’re learning from LIFE,—“the school of hard knocks” (laughter.) The girls are fine—the men are awful. Insecurely boastful; great intellectual pretension and bone-ignorant. Here’s “Wilder’s Law”—a man between 18 and 25 who for several years has done nothing becomes a misery to himself and a bore to others. It is written into the human constitution that MALENESS means work: homo faber.159 The British aristocracy is no ball of fire, but it would long ago have struck out but for the law of primogeniture—only the oldest son got any dough: his brothers had to go into Army, Navy, Church, Diplomacy, or “running the Estate.”

Look about you.

Went to Boston for 3 days.

Saw Midnight Cowboy. Much to admire. Some splendid performances. Something’s missing. I shall read the book to find out. (There were Long Lines at the Box-office)

Mia was delighted to receive that book from you and with its inscription.

She’s a very interesting girl. In my opinion her career is in great danger if she plays any more of those hex’d girls.160 Her directors don’t seem to distinguish between girls conditioned to neurosis and mentally arrested. She’s strong healthy and intelligent and she’s being forced into the straight jacket of an “image” which the public will soon weary of.

At present she is overwhelmedly in love. In a few weeks she will marry Maestro Previn.161

I returned Monday from Boston to find this community like a cow that’s been hit on the head with a mallet.

They’d had to go through their exaltation about the moonwalk and their learning of the squalid Edward Kennedy behavior on their own doorstep.

Tough.

JLH,—you’re as crazy as a coot, if you think I could enjoy conversation with the knowledge that someone was “taking notes.”

So start reshuffling what you take to be your image of me.

I suspect you of being deficient in a sense of humor.

We’d better not meet—I’d constantly distress you.

As it say<s> in you-know-what book when other people are bellyaching about the incommunicability* of human-to-human, about their “loneliness”, about the bondage to a technological civilization I get more and more elated, euphoric, happy, frivolous, trivial; and when others are in ecstasy about their halucygenic visions and their love-of-all-mankind and their kinship with the universe I get more and more sombre and metaphysically depressed. I’m terrible.

Arrange the flowers, sure; pet the cat, sure; but also do a number of hours daily of relaxed but single-minded work.

Glad to hear from you.

Old

TNW.

317. TO MIA FARROW. ALS 2 pp. Yale

Last five days at Neues Posthotel, St Moritz,

Feb 2. 1970

Dear Mia:

Ruth has given me your address and suggested that I write you—and I always do what Ruthie suggests, especially if it’s something that I want to do, too.

I hesitated a bit, but then I said to myself: January and February are the two most cheerless months in the year—especially in England and New England—sunless, heart-in-your-boots months—and a letter from a friend that loves you is a cheerful thing on your breakfast tray.

My thoughts often return to the radiant gifted FRIEND you’re waiting for (gifted by Papa and gifted by Mama).162 My niece is to have a baby in April. You know the Spanish idiom for having a baby—dar luz a: to give light.163 So Spanish! I’ve seen you with your own niece and an unforgettable sight it was.

I try to imagine what your life’s like while you’re waiting. I follow the London papers and saw Andre’s concert there and read the news of his forthcoming American tour. I wish Ruthie had told me what your plans are. Well, mine are fairly set: go to Milan Friday—two weeks—then to Genoa (stay in nearby Rapallo a few weeks)—take ship to Curaçao (Central America)—go slowly up the Carribean (I spelled that wrong, I think)—visit my mother’s sister, 88—in Florida—then to Martha’s Vineyard, end of April, with only a few days in New York and at home. I’ve been working hard—some stuff that’ll make you laugh, I hope. With the years I’m getting less gloomy.

My thoughts keep returning to the time when the Chichester Festival approached you about doing a play. Romeo and Juliet would be best, but London and New York have been—for the time—surfeited with that in both film and ballet. I still dream of The Wild Duck for you, but your idea of A Doll’s House is fine. I’ve never seen a very young Nora—who has? It’s about maturing: it’s about deepening spiritual insights. She’s made some frightening mistakes—but through ignorance, through love of her husband and children. Now she resolves to live correctly, truthfully,—but the person who is nearest and dearest to her doesn’t understand this “new Nora”, this moral urgency.

You’re a born actress. I dream of you constantly returning to the theater. And that’s best in London with all those companies with that continual variety of good parts and plays. Look at Irene Worth—two years ago a great success in Heartbreak House (Chichester and London); then with the National Theatre with Gielgud in Seneca’s Oedipus; now there<?> with the Royal Shakespeare Company in Tiny Alice.164 Well, she writes me that she’s to play Hedda in Stratford-on-Avon, Canada (where years ago she did All’s Well that ends Well and As You like it with Alec Guinness.) She’s just written me asking for my “ideas” about Hedda. All my life I’ve had ever-changing ideas about Hedda, but I haven’t any more. I don’t like plays about clinical cases, especially destroyer-women. But I love Irene’s clear pursuit of “good plays in good companies.”

But that’s not the important thing just now. Now I see you sitting before an open grate in Eaton Square, gazing into the live coals and dreaming. From time to time you put on the record of Albinoni’s Adagio—but that’s too sad. A Mozart—have you Klemperer’s recording of Mozart’s Serenade for Thirteen Wind Instruments? Maybe Andre has recorded it, in which case forgive me recommending another. At intervals you turn the pages of one of these “art books” that have reached such a perfection in our time. Your eyes fall on Giotto’s The Virgin’s meeting with St. Anne. Both are very pregnant and there is such a hushed solemn gravity in their faces, in their embrace, as takes your breath away. Don’t take time to answer these rambling thoughts, dear Mia. I put an address on the back of the envelope that will reach me for the next four weeks, on the chance that there is some way in which I could be useful to me<you>.

LOVE to all three of you

your devoted

uncle Thornton

318. TO JAMES LEO HERLIHY. ALS 2 pp. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Milan Feb 12 1970

I don’t know whether you’re still a Roman Catholic in good standing, but I’ll tell you a story that will reawaken old pieties. Yesterday was Ash-Wednesday. The carnival season came to an end,—carne = meat; the season before Lent when you could eat meat.

But we in Milan can eat meat for three more days—the only place in the WHOLE DEVOUT WORLD where one can eat meat without sin. Because we are enjoying the Carnivale de Sant’ Ambrogio. Centuries ago this city had been smitten by the plague; we died like flies. Finally as Lent approached the pestilence abated. And our good Archbishop—later our Patron Saint—St Ambrose passed a miracle. The survivors of that terrible time needed to eat meat to keep up their strength. So our wise and tender father and leader announced that fasting would be postponed for three days. So ever since the City goes wild with feasting and rioting and civic pride while the rest of the world goes into sackcloth and ashes.

I hope the tears are rolling down your cheeks like marbles.

Pass the wine and have a little more of this steak; it’ll keep up your strength.

x

I’d go crazy, if I weren’t pursuing some hobby—absorbing, totally occupying train of inquiry. At present it’s Greek Vase-painting. I’ve lived 72 and 10/12 years without giving it a thought. For something I’m writing I needed just a small bit of knowledge about it.165 (Not what they call research: I don’t do research—that’s why I make so many bloomers<bloopers?>.) Just enough to make a bit of literary magic about it. Couldn’t get any books up at St Moritz, so I came down here and picked up a few. Fun? yes and more than that—exaltation. Also, for what I’m reading I felt I should know something about the Tibetan mandala. Before that it was Levi-Straus and structuralism. I think I told you about that. Now for these hobbies I hook on to a subject and read what the authorities have to say and then I start and construct my own theories. Every hobby is also an exploration, a constructive question-answering journey of my own,—“creative”, as they say in college classes. Within no time I’m saying that those authorities, those professors are blind, stupid, academic-obtuse. These glorious objects were painted at a time when Athens was at its pinnacle—the great architecture, and sculpture, the tragedies were being written, the lung-expanding comedies. And yet: Athens was in mortal danger—the Persians were advancing; the war with Sparta was ultimately inevitable.

It seems never to have occurred to the scholars to ask what is the relation between the scene pictured on one side of the pot and the scene picture<d> on the other, why Bacchus and his frantic women-followers on one side and Hector taking leave of Andromache on the other. God damn it … in times of mortal danger (which is also any time in life, if you’re really alive) you must encompass both poles—life and death (Bacchus’s vine-plants which renew themselves annually—the life-enhancing force—and the death of Hector, the great and good. That’s where the mandala comes in, too. James-the-Lion, see to it than <that> in every novel you write (NOVEL: a window on Life—and on all life] you touch all bases: death and despair and also the ever-renewing life-force, sex, courage, food, the family. I think you’ve always done that anyway, but know that you’re doing it. Touch all bases to make a home run.

x

I’m shy of writing you because you want to make me into a guru of some kind. More and more I see the havoc that’s made in life by overvaluation. After overvaluation there’s always a bitter disillusioned morning-after. Marriages are wrecked by it; father-and-son relationships are wrecked by it. It’s popular name is idealization. It would be terrible if we didn’t have it—it’s present everywhere around us, but oh, if we could only guard ourselves against OVER-valuation, we save ourselves a lot of shipwreck.

x

This is the Beethoven anniversary year.166 He’s not my topmost music-maker but he sure was a wonderful man. Now that you’re as rich as Croesus, give yourself a journey from the early Septet through the quartets and violin sonatas to those last quartets. (I’ve never been able to hook on very much to the piano sonatas.)

x

I’m soon starting home by the slowest ship on the sea.

I’ve been writing some stuff that’ll maybe make you laugh. You don’t hate laughing, do you? Remember true laughing requires a wide departure from the self and its self-preoccupation. But, after all, I don’t know you and maybe you’re a buoyant roaring boy.

If Tennessee’s167 still there, give him my deep deep regard. Forgive this long-delayed answer to your letter and be sure that I’m always glad to receive one from you—now it must be via Hamden. I just got a buoyant letter from Mia—she reports that she and André are sitting in London happily awaiting the baby that’s kicking boisterously within her. She just rec’d the British Academy Award nomination for best actress.168 hope all’s going great with you and the work.

Your old friend

319. TO AMOS TAPPAN AND ROBIN G. WILDER.169 ALS 2 pp. Private

Last day in Miami Fla.

April 18 1970

Dear Robin and Tapper

The great-uncle is as impatient as you are for the entrance on the scene.

I know you’re looking about for a baby-sitter. Well, as you know, I’m a stay-at-home. I don’t mind yelling and screeching as long as I’m certain that baby hasn’t swallowed a string of beads or something<.> I’ll assume the child is merely practicing to be an opera singer.

So when you’re invited out to dinner just bring the bassinet up to my study (with the bottle and a page of instructions—your phone-number and the phone-numbers of the half-dozen best pediatricians in town (headed by my old friend, Dr. Betsy Harrison<?> who can always soothe me, too)

My terms are very high but I offer these services gratis to great-nephews and double-gratis to great-nieces.

So lots of love to dear little Gloriana or sturdy little Augustus.

And thanks for the birthday greeting.

love

Uncle T.

Wilder family, Thanksgiving 1970, in Amherst, Massachusetts. Left to right: Amos N. Wilder, Isabel Wilder, Robin Wilder (holding Amos T. Wilder), Amos Tappan Wilder, Catharine Dix Wilder, TNW, Arthur Hazard Dakin, Winthrop S. Dakin.

Wilder family, Thanksgiving 1970, in Amherst, Massachusetts. Private collection.

320. TO GENE TUNNEY. TL (Copy)170 3 pp. (Heading 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Private

December 4, 1970

Dear Gene:

There are certain long-time deeply valued friends whom I find it strangely difficult to write letters to. One of them is Bob Hutchins (President of “my” freshman class in Oberlin, 1915; my boss when he was President of the University of Chicago). Another, Bob Shaw, now director of the Atlanta Symphony. Another is your so-much-admired self. I think the difficulty is that I have to write so many letters on the relatively superficial discursive level—, that I shrink from the danger of falling into mere chatter with these friends. I notice that those two “Bobs” seem to understand this “bloc” (and perhaps suffer from it, too), because when we do meet—so seldom—we behave as though no lapse of time had taken place at all.

Just the same, it is not right; I think of you and dear Polly often.171 I think of you often with the most affectionate laughter—the fun we had at the training camp in The Adirondacks; or with delighted surprise, as when I was trotting beside you and you turned to me (after stepping on a caterpillar) and quoted solemnly:

“The humblest beetle that we tread upon in corporal sufferance feels a pang as great as when a giant dies.”172

(Scientists tell me that Shakespeare wasn’t quite right about that.)

Or I think of you with quiet joy, as in that beautiful wedding in the Hotel de Russie at Rome; or with apprehension, as when you felt indisposed in Aix-les-Bains.

Recently I have heard that you have been suffering considerable pain. Day before yesterday I met Mary Jackson173 in the train going to New York; she was on her way to see Polly. I sent my love and we talked of you both with much admiration and love.

No one lives to my time of life without experience of pain—of body and of spirit. My trials of body have not been as extensive or as racking as yours, but I have known them. Each person meets these demands in a different way. I am not a religious man in the conventional sense and cannot claim that consolation that is conveyed in the word “trial” (“God has sent me this ordeal as a test of my confidence in Him and in His ordering of the world”); nor am I willing to endure pain in that spirit that so many noble men and women have done—merely stoically. My strategy—if I may call it so—is to attempt to associate myself to persons I love and honor in the past or to multitudes unknown to fame and barely alluded to in history. At three in the morning carried through the streets with a bursting appendix I murmured “This is nothing to what Dr. Johnson endured when he was “cut for the stone” (gall stones); ever after he took to dating his life from that experience. In 1951 while teaching at Harvard I was “struck down,” as they say, by a sacroiliac dislocation. I was barbarously tended at the Harvard Infirmary (where they thought it was some kind of laughable charley horse). I was finally transferred to Massachusetts General. From time to time I could “lose myself” in an attempt to join those who had suffered ten times what I was undergoing—political <illegible>, heretics, the victims of Nazis, the great and the good. Physical pain is the summit of aloneness, of solitude. I tried to catch glimpses of a companionship in Endurance.

Very certainly I shall have to face such hours again—I shall think of you; I shall “telegraph” you.

The doctors have just “sprung” me after months of treatment—deterioration of eyesight and hypertension—and next week Isabel and I are taking a slow, slow ship, the Christoforo Colombo, to Europe: New York, Dec. 10—Venice, Dec. 23. Soon after Isabel returns here to look after the house; I stay on somewhere over there to resume work after this long interruption.

In the meantime I send you affectionate wishes for improved well being, memories of many happy hours in your company and in Polly’s and my hope that you can understand and forgive my foolish immature difficulty about writing letters.

Love to Polly.

Ever,

(Signed) THORNTON

Mailed Dec. 11

321. TO EILEEN AND ROLAND LE GRAND ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Private

April 25 1971

Dear Roland; dear Eileen:

Many thanks for your letter.

Yes, we know Julian’s news.

We have met Damaris and found her most attractive and likeable.

No doubt you were much surprised at their decision to be married in Philadelphia when they were also planning to go to England so soon after to see you there (“To see the relatives” he wrote us.)

It would be hard to make clear to you what a thorough revolution has taken place in the mentality of young people during these last years. You are certainly aware of it—it is world-wide—without however grasping the extent.

They wish to do things their own way. No fussing, no interference, not even counsel. There are very few families that have not been confronted by this “independence,” often to a heart-breaking extent. The root of it seems to be a shrinking from any claims that may be made upon them—emotional claims, approval or disapproval. This isolation often makes them unhappy but they will it.

I have watched this increasing for more than ten years and have seen it in my own near-kin.

You may have noticed that in all the years that Julian has been here I have never called on him in his rooms in Philadelphia.174 Nor—though a very concerned godfather—have I intruded with a word of advice (unless asked, and I was never asked on any matter of importance) until about two months ago, on the delayed appearance of a thesis.

What kind of wedding do they want? Do they really want us to be present? Julian has never mentioned any church affiliation. I think it very likely that they want what in England you know as a visit to the Registry Office.

I love Julian and am ready to love Damaris,—may they long be happy—AND I am prepared to let them make all the conditions in this matter. Are Damaris’s parents planning to cross the sea? In Our Town the congregaters and especially the mothers weep copiously. Those days are completely over.

I have been “poorly” as they say in the American language—eye-doctors, ear-doctors—respiration-doctors. Now at 74 I don’t bustle about easily. I would like to propose that I give the young people a dinner in New York on the eve of their flight to England and let them go to the Registry Office with their co-evals.

In the meantime I await clearer instructions as to what the young people want. Do share with us how you feel about all this.

love

Thornton

322. TO ENID BAGNOLD.175 ALS 4 pp. (Stationery embossed Post Office Box 862 / Edgartown, Massachusetts 02539) Yale

It’s June 29th, they say; anyway its 1972 and I’m 75 years old, so I’m just in condition for a little epistolary flirtation.

Dear Enid:

So you’re posting memory tests!

Well, you flunked right off: I’ve never worn a bowler hat or “growler” 176 in my life.

What did you wear? You wore a sort of land-girls uniform, just short of farmer’s trouser overalls, because you took me around and showed me the cows you’d milked, the cabbages you’d hoed, and you were adorable; and two weeks later, you were just as adorable, very ladified, when you had dinner with me at Boulestins (where Paula177 used to meet her gentlemen friends before she married into the Tan-querays.)

But I have forgotten the third way to open a play.

In the intervening 30 years, I’ve changed my mind often.

For a time I loved opening in silence. Feed the audience’s eye with the stage-setting, if you have one to offer. Then a bit of pantomime in silence, to capture their curiosity. (Hamlet: nothing.—then a sentry—go—Gruff exchanges. Then a bull’s eye: “Tis bitter cold and I am sick at heart”). The greatest living dramatist-actor-regisseur, whom you’ve just been seeing in London<,> Eduardo di Filippo178 has wonderful silent openings. But I’ve totally forgotten my third recommendation of 30 years ago. Did you notice that after calling my first the “Figaro” opening, you gave as my second “Sir, you have raped my daughter!”—which is precisely the opening of Don Giovanni. I have never doubted that Mozart had a large share in the libretti of his operas—pace Da Ponte who is now resting in the cemetery of Trinity Church in Wall Street, New York.179

You are quite right that Ruth Gordon played in a play of mine—just over a thousand showings and she never missed a performance!180—but far from having quarrelled she is my dearest friend and she and Garson are have<having> dinner with me tonight,—I having dined with them four times in the last two weeks and having put down my foot about the ignominy of such one-way hospitality. I must take them out to a public place—because Isabel has left me alone on this island to work and I am wallowing in bachelor squalor—sheer Heaven!—and writing like a fiend possessed.

Oh, I wish you were dining with us tonight: I cannot yet give you the menu, but here are some items on the conversational agenda:

Simone de Beauvoir’s La Vieillesse. (As Mrs Fiske181 said of a rival actress’s performance “She played all evening with her hand firmly on the wrong note.”<)> She seems to have no organ for the perception of innerness … but then that’s very French … apart from Pascal (who is apart from everyone) the only great French authors who had that gift were Montaigne and Proust—and both their mothers were Jewesses … Gertrude Stein told me that Picasso’s mother said (another Jewess!): “The only time that I realize that I am the mother of a grownup son is when I look in the mirror.”

Simone de Beauvoir’s La Vieillesse. (As Mrs Fiske181 said of a rival actress’s performance “She played all evening with her hand firmly on the wrong note.”<)> She seems to have no organ for the perception of innerness … but then that’s very French … apart from Pascal (who is apart from everyone) the only great French authors who had that gift were Montaigne and Proust—and both their mothers were Jewesses … Gertrude Stein told me that Picasso’s mother said (another Jewess!): “The only time that I realize that I am the mother of a grownup son is when I look in the mirror.”

Your dear self—an account of your first play produced I believe in Santa Barbara—with that redheaded girl (Fitzgerald?) about an understudy who did away with the star. I wasn’t there but I read about it avidly.182

Your dear self—an account of your first play produced I believe in Santa Barbara—with that redheaded girl (Fitzgerald?) about an understudy who did away with the star. I wasn’t there but I read about it avidly.182

A stern injunction not to neglect HANDEL—the manly nobility of his pathos, the buoyancy of his fugues (the twelve concerti grossi: he had suffered a stroke a year and a half before composing them), the sunburst splendor of his choruses in praise of God (Israel in Egypt, Theodora, and passim.<)> Be not ungrateful of the gifts of Heaven.

A stern injunction not to neglect HANDEL—the manly nobility of his pathos, the buoyancy of his fugues (the twelve concerti grossi: he had suffered a stroke a year and a half before composing them), the sunburst splendor of his choruses in praise of God (Israel in Egypt, Theodora, and passim.<)> Be not ungrateful of the gifts of Heaven.

Dear Katharine Cornell with whom I am invited to lunch next Saturday, fragile but with an increasing etherial beauty and spiritual radiance.

Dear Katharine Cornell with whom I am invited to lunch next Saturday, fragile but with an increasing etherial beauty and spiritual radiance.

The weather.

The weather.  The locust-crowds of tourists; etc, etc.

The locust-crowds of tourists; etc, etc.

As this letter is not without its flirtatious aggression I must add (to make you jealous, I hope) that although I am 75 years old I received this week two letters, not without notes of tendresse, from two actresses: one very old, Miss Mia Farrow and one, very young, from Miss Irene Worth a-tiptoe for Corsica. Do you know Goethe’s poem to himself at eighty:

Du…….

Munter Geist…..

……

”Du auch sollst lieben“183

There is no age limit to creativity, but there are two required conditions: EROS at your right hand, Praise of life at your left.

Much love to the lady of Rottingdean184

devotedly

Thornton

323. TO MIA FARROW. ALS 4 pp. (Stationery embossed Post Office Box 862 / Edgartown, Massachusetts 02539) Yale

Oct 4. 1972

Mia Mia Carissima:

Loved your letter.

Loved your photos.

Loved your postscript (from André).

There is no news here except heavenly weather <last two words circled, with an arrow to text in left margin> THREE DAYS LATER: STILL ONE PERFECT DAY HAS BEEN FOLLOWING ANOTHER. and hard work. The Kanins were twice off the island for some time; they returned last night and we shall see them tomorrow here—when Isabel will cook some good things for them.

Your brother John and his co-worker Alden and a very nice girl came to dinner with us at the BLACK Dog. We had a very pleasant time and I think they did; but I must confess with chagrin that although I taught (and had conferences) for twelve years with boys and young men and young women between the ages of 15 and 25 (Law renceville School, University of Chicago, and Harvard) I find it very hard to reach the center of young persons of this generation,—the center of their interest. The center of their curiosités—the word has a richer and more dignified sense in French than in English. Whatever those centers are they keep them locked up from us older persons. But I like them and wish them enormously well.

I’m delighted that you are “reading” passages from the Midsummer’s Night’s Dream with MENDELSSOHN’S music under Erich Leinsdorff<Leinsdorf>. I can well understand that you’re nervous because it’s an aspect of the actress’s art that’s gone out of fashion for half a century. It’s that kind of “extending” yourself that’s going to be very useful to you as your career developes. That kind of presentation used to be called the mélodrame. Some Sunday evening ask some friends in to hear you read Richard Strauss’s setting of Tennyson’s Enoch Arden for speaker and piano. André will enjoy it, for the piano part is positively luscious. Your problem will be to keep the audience from laughing (I suppose it’s really for a male speaker) but it does have a real eloquence, however dated, like turning over the pages of old family albums.

Do you know the Quaker use of the word “concern”? “I have a real concern for thee,” they say. It means a sympathetic participation at a deep level,—not pathos, not anxiety, not mere wish “for every happiness” but a sharing in friendship of the recognition that basic existence is hard for everyone and can be sustained in Quaker quiet and reverence and innerness. My concern for thee comes from my knowledge that you carry so many concerns for others, and so well and so bravely.

Please have a concern for me. As my book185—I have been working very hard—approaches it’s end more and more earnest notes about suffering in life insist on coming to the surface—and I want to “get them right” and then the book will end in a blaze of fun and glamor and happy marriages (at the annual “Servants’ Ball” at Newport!); and you know what author I am trying to emulate.

What a lovely coronet of flowers you wear in the “wedding picture” —with a dress of a lighter color that’s just what you should wear while reading A Midsummer Night’s Dream—a mixture of Titania, without a royal crown, and of the dancers on the green when England was “Merrie England”—Perdita in A Winter’s Tale. Lovely.

What a sad thing for us that we can’t stay here into November and have some more happy hours at “your place” and at “our place.” But Isabel’s been under some strict regimen and has to see her doctor, and I have to interrupt my surprisingly happy “working vein” and attend to postponed matters in New Haven and New York.

We have changed our plans. We are not going abroad until early January. We have “escaped” too often the “family reunions” of Thanksgiving and Christmas—I far oftener than Isabel. My brother has just turned 77 (and is in buoyant health) and my great-nephew is two months younger than your boys—so we have a wide range at those celebrations! We sail on “our old friend” the “Cristoforo Columbo” and disembark at Genoa—maybe a few weeks at Rapallo and then back to our favorite hotel in Zürich—moderately good opera and often very good theater—rooms over the lake—an unexciting but congenial city. Isabel will return to Hamden (having missed the worst of the New Haven-Hamden man-high snowdrifts, breakdown of public services and facilities: because of the “miracles” of technology, winter in a medium-size city is getting to be worse than winter on a remote North Dakota farm.<)>

I wish I could sit beside you at André’s concerts. (When Larry came over for the first time I used to sit beside Vivien at each “first performance”—Oedipus, The Critic, Henry IV Parts I and II—on his second trip she was playing with him, the two Cleopatras and The School for Scandal)<.>186 And—there’s no law against dreaming—I’d order the programs: Bach’s seconde suite; Bruckner’s V, VI or VII, Berlioz Romeo (again), Mozart G-minor, any Rossini Overture, Vaughn-Williams Pastorale, and Haydn, Sinfonia Concertante; Oh, yes, and I’d order André to direct a Mozart concerto from the piano and improvise the cadenzas on the spot. Did you ever imagine I could be so presumptuous?

My love to Matthew and Sascha. My love to Alicia. My love to Tina.187 My love to the Maestro.

My love to the dear Lady who joins us all like the diamond on a necklace of the choicest emeralds.

In which Isabel also cries AMEN.

Thornt’

324. TO RUTH GORDON AND GARSON KANIN. ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Private

April 20 1973

Dear Kind Kanins:

I’ve held this enclosure for weeks. Où est ma tête.. ?188

x

So I finished the plaguéd book. I’m accustomed to turn my back on a piece of work once it’s finished—but it’s something new for me to feel empty-handed and deflated,—to wake up each morning without that sense of the task waiting for me on my desk. Daily writing is a habit—and a crutch and a support; and for the first time I feel cast adrift and roofless without it. I hate this and am going to get back into a harness as soon as I can.

x

Received a composite letter from Mia/Irene Worth written from Mia’s dressing room at the Three Sisters<.>189 Irene’s full <of> appreciation of the simplicity and skill of Mia’s playing of Irina—Irene is now in rehearsal at Chichester in<as> Madame Arkadina.

The papers announce that Mia is to film The Great Gatsby at Newport.190 I wonder which place they have selected for setting.

x

I’m jolly well, thanks to Garson’s tirelessly acquired wisdom and his firmness with me. I take all my medecines.

April 29.

Another time-lapse.

This house is in constant muddle. The book was finished but portions come and go to agents, typists, proofreader (la Talma) all in a muddle of missing pages, crossed letters, incorrect pagination, etc.

But I don’t let this bother me much.

I was suddenly stung with an idea for a play and can’t wait to get to the island and get back in harness. I must find a chauffeur—either a divinity school student who’s glad of the job or O’Neil,191 if he can get away from the Royalton Hotel (he could only do that on a weekend when maybe it would be impossible—I hear—to get a ferry boat reservation.)

Went to NY for 3 days (lunch at the Players192 with Cass Canfield, Beulah Hagen and Isabel—in that private dining room—perfect); dinner at Laurent’s with Carol Brandt and her husband193—delightful time, but ouch!). Forgive me but I saw A Little Night Music194 without Hermione Gingold; I constantly forget that I am no audience for musicals. Was very depressed by the air-pollution; but have now recovered. Forgive the delay of this letter and accept

a load of love

Thorny

325. TO C. LESLIE GLENN. ALS 2 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Yale

June 24. 1973

Dear and Reverend Doctor:

So you became a Dr. at Stevens Poly195: Did you remember that I spent a week there as your guest—in your absence—taking walks and taking notes on the Hoboken that I would fantasticate in The Eighth Day almost half a century later?

x

I’m mortified and distressed and confused that there’s a sort of conspiracy going on around here to collect old letters that I wrote …. I think that gives the impression that I’m behind it and am pretentious and self-infatuated … I wasn’t supposed to know about it … Hell! It’s enough to make a fellow incapable of ever writing a spontaneous word again.196

x

Dear Les,—I shall never speak, read, preach, orate, act, or sing from any podium, platform, or even hearth-rug again. It’s at least 15 years since I’ve done it.

My revulsion from it was so sudden and so intense that it was like a prompting of The Inner Light, (or like Socrates’s daemon which never told him what to do, but what not to do.) Please convey graciously—as only you can—to your committee at the Corcoran197 my appreciation of the invitation and my regret that my disabilities—hypertension and deteriorating eyesight—prevent my accepting it.

x

Here’s a joke I heard. I told it to Isabel and she’s still laughing: Suppose that Wanda Landowska married Howard Hughes, divorced him and then married Kissinger—wouldn’t her name be

Wonder Who’s Kissinger, now?

Love to you and to dear Neville198 with felicitations on her birthday

And to you

Theophilus

P.S. I’m sending copies of this letter to the Archives of the International Geriatrics Society; the Lapaloosa Wilder Fan Club, Lapeloosa, Arkansas; and to the FB.I, who intercept all my sinister mail anyway.

TNW.

326. TO PEGGY AND ROY ANDERSON.199 ALS 4 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Redwood

Oct 11. 1973

Dear Peggy—Dear Roy

Dear Roy Dear Peggy

The postman is bringing you my new book.200

It will certainly seem a strange book to you,—all about Newport! A Newport in large part spun out of my own head. You will be sur-prised—and probably intrigued at my presumption. But it all takes place in 1926—almost half-a-century ago. It should be read as one of those historical novels—highly romantic and extravagant.

I hope you find some amusement in it, but I hope you find also an affectionate picture of the beauty of the place and then I hope you find—what the first reviewers, even the more favorable ones, seem to miss—a deep emotion behind most of the stories (its really a dozen novellas which finally “come together” and justify it’s being called one novel<)>. Please do find yourselves sincerely moved from time to time.

You’ll be relieved to know that there’s not a single portrait drawn from life in the whole book—least of all the hero, who is part “saint” and part rascal, a combination that is fairly rare in fiction.

x

I haven’t been well these last months—had a lumbago (slipped disc) from sheer fatigue after finishing the book and had two separate 9-day hospitalizations. Am better now, but limp about cautiously.

Had to cancel my trip abroad. I was slow convalescing because I’m so old.

x

I should have written you this letter before you received the book but my energy ran low.

I hope all is well with you and that you are rejoicing under the “glorious trees of Newport”

Ever affectionately

Thornton

and love to Kitty-Pooh

327. TO HELEN AND JACOB BLEIBTREU.201 ALS 3 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Columbia

Nov 3 1973

Dear Jack; dear Helen:

Delighted to receive your letter, though very sorry to hear of the trouble you have both been having with your health. I too have just graduated from the use of a “walker” (or “aluminum petticoat”) having been in the hospital 21 days for a slipped disc—my convalescence has been slow because I’m 76—but I’ve been cheerful inside and I see you are, with your lively recall of the Harrisburg days.

Naturally I’m proud to inscribe the book to you. The reviews have been generally favorable—a few LEMONS to keep me humble, but the big city reviewers don’t seem to get the point of the book (reviewers don’t read for pleasure but for pay and that dulls the perception.) They think it a topical book, picturesque social history, etc.

The hero as a child dreamed of becoming a saint—well, he fell far short of it but the dream remained and could not die. The book is about the humane impulse to be useful, about compassion, and about non-demanding love.

I hope you find it occasionally funny, too, but a very serious intention lies under the surface and becomes more evident as the story developes.

I’m sure Helen will see that it contains a great deal of homage to women (to all except “Rip’s wife<”>!).202

May you both be restored to excellent well being soon.

Even in our all-too-short meetings, I felt I was privileged to know you

with much affection

Thornton

P.S. The book returns under separate cover.

TNW

328. TO MICHAEL KAHN.203 ALS 4 pp. (Stationery embossed 50 Deepwood Drive / Hamden, Connecticut 06517) Yale

Nov. 8 1973

Dear Michael Kahn:

Greetings.

I do indeed remember your fine work on those plays and remain forever grateful to you.

I’m sorry about my delay in answering you, but it was necessary.

Several years ago I gave the rights to make a movie of The Skin of Our Teeth to Miss Mary Ellen Bute (Mrs. Nemeth) who made that delightful film fragment of Finnegans Wake.204 In the agreement between us I promised to veto any showing of the play within 50 or 60 miles of N.Y. She has been held up by financing but is eagerly planning the film.

I had to send out tactful feelers as to whether I remember the “mileage” correctly etc. At last she has replied that she would look favorably on a production of the play at Stratford.

Many have told me that they thought Miss Shelley205 to be the next authentic comedienne of this country: Ada Rehan → to Mrs Fiske—to Ina Claire—to Ruth Gordon. (Talullah was a wonderful being, but she never gave the same performance twice.) I’d only seen Miss Shelley in The Odd Couple but I spotted the real biz.

So all’s clear and I pass you over to Bill Koppelman at Brandt and Brandt.

I haven’t seen many SKIN<s> but the ones I’ve seen where it worked best were in Germany. They knew what is was about: survival, terror and hope. They played it for the story line. They didn’t stop to fool with gimmicks—there are gimmicks enough in the play itself—They played them for real. Georgio Strehler in Milan, being an ardent communist, directed the Antrobus family as members of the hated bourgeoisie—idiotic, vapid poseurs. Others—over here—are so busy horsing around that the curtain-scenes are a mere shambles of noise and confusion and miss any dynamic force. (One ended the play with newsboys rushing down the aisles crying “Extra—the atom bomb has fallen”—catastrophe number four.<) >

It is my impression that the structure of the Stratford stage dissipates tension—everything becomes “spectacle.” The end of Act One is all focus’d about one fireplace: the end of Act Two is all focus’d about one narrow pier leading out into the sea.

x

Menace hangs over the people in every act.

Sabina is only aware of it at intervals. She refuses to face facts—she thinks one should live for pleasure alone (for a short time she seduces Mr. Antrobus to her position.) Her pathos is when she sees that events are too big for her to grasp. Mrs Antrobus—absurd though she sometimes seems to be—is the pivot of the play. I’ve never seen an adequate Mrs A.—dear Helen Hayes didn’t have the voice or the stance206 …it’s hard to make humorless women sympathetic, but she must be sympathetic because of her single-minded will to survive.

Play it for melodramatic passion, and let the jokes take care of themselves,—the flare-up between father-and-son in the last act will be felt as organic in the play.

I’ll hope to see you during the spring and have a good talk.

In the meantime enjoy the project.

Ever cordially

Thornton Wilder

329. TO CATHARINE DIX WILDER. ALS 2 pp. Yale

Box 826 Edgartown Mass 02539

Sunday June 30 1974

Dear Dixie:

The weather’s been miserable down here and I keep hoping that its better up north by you.207 I don’t mind honest rain but we’ve been having two kinds of weather I don’t like: dull shilly-shally drizzle and hot weighty humidity—oppressive to man and beast. Whenever Isabel’s not around I tend to relapse into “bachelor squalor.” (I’m not really as untidy as that, but comparatively.) Since, like you I’m still convalescent (still, from that slipped disk) <(>I tend to let certain niceties lapse.) As not a soul has been in this house since she left except the master a measure of laxity can be presumed. Isabel arranged for a “girl” to clean up from time <to time> but “occasional help” in an overcrowded pleasure resort is proverbially unreliable. I make most of my own meals (huevos rancheros and Irish stews—from cans<)>—but I go out to dinner every other night and invite guests. The actor Robert Shaw is here, star of JAWS which is being intermittently shot all over the island. Bob dedicated a play to me—“Cato Street” which was played in England with Vanessa Redgrave in the lead, but had a short run.208 The other night I took his wife actress Mary Ure and the governess of her children came out to dinner with me and I plied them with Champagne and we were joined by the eminent and elderly cellist Otto von Copenhagen and I made up for a week’s silence and solitude. The Garson Kanins have been in New York and I’m going out to dinner with them tonight, but on the whole silence and solitude agrees with me very well.