Six weeks after visiting Jamy, we’re sitting on the patio of the Cheu-vront restaurant and wine bar on Central Avenue in Phoenix, long-stemmed glasses in hand. The light rail train running up the middle of the avenue scrapes and clanks its way northward and makes a stop a few hundred yards away. A sole figure descends onto the platform and walks toward us, a black bag swinging with each step. It’s Anthony Barnhart, or Magic Tony to his fans, and he’s carrying the tools of his trade—playing cards, a little bag of coins, red sponge balls, and prepared ropes for tricks.

Magic Tony is our mentor and magic instructor, and we’re meeting him for another rollicking session of “teach the scientists how to prestidigitate or at least pull off some classic magic tricks without embarrassing themselves when they try out at the Magic Castle.” Tony is a big guy with a black crew cut and a jovial demeanor. During the week, he’s a PhD candidate in psychology at Arizona State University in Tempe. But on Friday nights he dons his dorky red fish tie (“I just wear it for the halibut”) and his leopard print shoes (“It took two leopards to make these, but it’s okay because they were babies”) and strolls from table to table doing tricks at the Dragonfly Café in North Scottsdale. Customers love him. We do, too.

Tony grew up in Milledgeville, Illinois, where he had a swim coach who taught magic on the side. Along with the Australian crawl, seven-year-old Tony took beginner’s magic lessons and was hooked. He also learned a critically important lesson: magic is about entertaining the audience. Young magicians should not focus on methodology at the expense of theatrics.

A magic shop, the Magic Manor, was located an hour away in a strip mall in the neighboring town of Rockford. Like many young boys who fall in love with magic, Tony spent countless afternoons at the shop rummaging through bins and taking group lessons, where he was always the youngest person in the class (and the quickest learner). He attended Tannen’s Magic Camp on Long Island for two years in a row. His favorite memory of getting fried (that is, fooled badly) happened in his dorm room in the middle of the night. He was rooming with two other campers. At about two in the morning, the counselor woke them up and said to Tony, “Think of a card.” He did so, and the counselor subsequently named the card that Tony had sleepily thought of (it was the seven of clubs). “I’m still not sure how he did it,” says Tony. “He must have primed me in some way, but I can’t be sure. I sort of like not knowing.”

Today Tony is going to teach us two methods used in the Ambitious Card routine. This famous trick can be done in an infinite number of ways, but the ones we are about to learn are especially germane to how magicians trip up your visual system. The magician asks you to choose a card, any card, from a deck. You do so and then place the card in the middle of the deck. The magician snaps his fingers over the deck and voilà—your card has mysteriously risen to the top. It is an ambitious card—it rises through all the other cards every time.

The routine is renowned in the annals of magic as the trick that fooled Harry Houdini. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Houdini was the most famous magician in the world. Whereas he had earned supreme confidence in his abilities to pull off spectacular escapes, he was perhaps too confident in his abilities in close-up magic. With fulsome bravado, Houdini issued a challenge to all magicians: Show me any trick three times in a row and I’ll tell you how you did it.

At the Great Northern Hotel in Chicago in 1922, a gifted magician, Dai Vernon, met the challenge by demonstrating his version of the ambitious card routine. Vernon, known as the “Professor,” was more than a match for Houdini. He was one of the best sleight of hand artists who ever lived and, with another magician, Ed Marlo, possibly the most influential card magician of the twentieth century. Vernon was a brilliant inventor of close-up effects with cards, coins, balls, and other small items.

Vernon asked Houdini to choose a card and sign it, in ink, with his initials. The card went into the middle of the deck. Vernon snapped his fingers. Houdini’s card was on top.

Houdini was stumped. “You must have a duplicate card.”

“With your initials, Harry?” asked Vernon.

Vernon repeated the trick three times, using a different method each time. Houdini was incensed. He couldn’t figure out how it was done. Vernon did the trick four more times. Still Houdini was fooled—though he never admitted it publicly.

Sleight of hand magic, when done well, is miraculous to behold. (The word “sleight” comes from Old Norse and means cleverness, cunning, slyness.) It is usually performed close-up, within a few feet of a spectator. There are hundreds of different sleights. Some involve misdirecting your attention (we’ll get to those in chapter 4). Others exploit foibles of your visual system. Indeed, the role of visual perception in sleight of hand is fundamental to magic.

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

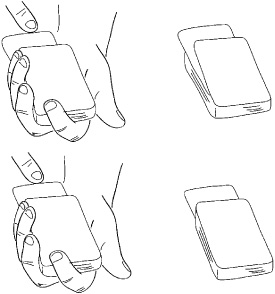

It’s no coincidence that magicians use decks of playing cards to convey their magic. Cards are remarkable in that they are stiff, yet very thin. They fit inside the palm of your hand and can be hidden easily. They can be shuffled, fanned, flipped, palmed, cut, gripped, and pocketed. Our first lesson today is the double lift, probably the most basic and most central sleight in the magician’s repertoire—and a key feature of Ambitious Card routines. The trick is to turn over two cards on the top of the deck while making it look as if you are flipping only one. It’s that simple. But when it is used at the right time in concert with other types of misdirection, it is utterly astonishing. Dai Vernon was a master of the double lift. Say your card is the ace of clubs. The magician fans the cards and you put the ace in the deck. As he closes the fan, he puts one card on top of the ace and surreptitiously marks the spot, called a break, with his pinky finger. He makes a quick cut of the cards so that the ace is now the second card from the top. Then comes the double lift. He lifts two cards so that the ace is faceup, on top. It is the ambitious card.

The magician smiles and says, “Yes, it is an ambitious card.” He double flips the cards facedown once again and then takes the top card (which you think is the ace but of course it is not) and puts it in the middle of the deck. He snaps his fingers and turns over the top card, which is—the ace! It is surely ambitious, and you are dumbfounded.

Magicians train for thousands of hours to double-lift without revealing that they are “handling” the cards. They must train their fingers to deftly lift two cards while convincing you that they are lifting only one. This involves various maneuvers such as putting a small crimp in the two cards so that when they are facedown the magician can feel them as one. When the cards are flipped, the crimp is released and the cards lie flat. In mastering this sleight, magicians must be able to make the moves without paying attention to what they are doing. Vernon, in a 1961 book, Stars of Magic, warned that many magicians screw up the double lift because they are terrified that the two cards are going to separate. “A playing card,” he said, “is a light and delicate object and should not be turned over like a cement block.”

So how does the double lift fool you each and every time? Why can’t your visual system track the cards correctly? It has to do with your center of vision. If you were going to detect two cards pressed firmly together moving as a unit, you would have to put your eyes inches in front of the magician’s hands and stare at the cards as if under a magnifying glass. Even then you might miss the sleight of hand.

The reason for this is that your visual system has very poor resolution except at the very center of your gaze. The cards are so thin that your vision is not up to the task of distinguishing them, especially in the hands of a skilled card sharp. Your center of gaze is called the macula—the region near the center of your retinas packed with photoreceptors. It, along with the fovea (the very center of the macula and the part with the very highest resolution), is responsible for high-acuity vision. It’s a piece of your anatomy that is so specialized it has its own set of diseases, including age-related macular degeneration. In fact, macular degeneration is the most common form of blindness in older people, as maculas slowly die over the course of a few years. Without maculas, you can see only with your peripheral vision, which has very low resolution. You navigate by seeing the world in terms of what appears off to the sides of your head.

END OF SPOILER ALERT![]()

Tony shows us another way to do the Ambitious Card routine called the Vernon Depth Illusion (also known as the Marlo Tilt because the two magicians developed it independently). Long after Houdini died, Vernon continued to refine the trick with diabolical insight into visual processing.

In this sleight of mind—captured on rare film footage in the 1950s—Vernon asks you to choose a card and sign it.* He takes the card and clearly sticks it into the middle of the deck, slowly and purposefully, so there can be no mistake that it’s your card. Then he flips the top card of the deck, and voilà!—it’s your signed card.

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

It is an incredible, astonishing, maddening event. Here is how he did it.

After Vernon receives your card, he twists it slightly and sticks it partway into the center of the deck from the back. The twist ensures that the card does not enter the deck. Instead, it forces others cards to protrude where you are looking—at the front of the deck about halfway down. These pushed-out cards reinforce the idea that Vernon is really planning on pushing your card into the center of the deck. But it’s a ruse. While resquaring the deck (pushing the cards back in), as if to fix his mistake, Vernon tilts the back of the top card of the deck slightly upward. From the perspective of where you are standing, you cannot see the tilt, though there is now a gap of almost a centimeter between the top card and the next card down, as seen from the back of the deck.

Vernon then takes your signed card and slips it into the deck at the bottom of the unseen gap. From your vantage point it looks like it is going into the middle of the deck, but in fact it is now the second card down. You don’t notice this discrepancy for two reasons. First, from your perspective, you can’t see the tilt of the top card. It never occurs to you that he could be sliding your card into the second-card-down position, directly under the top card.

Second, your visual system convinces you that your card is much farther down than the second position. It looks to be in the middle of the deck, in approximately the same position as when Vernon first “accidentally” pushed out the cards with the twisted card. You saw other cards pushed out as it was “inserted.” But did you really see it go in?

The magician can push the card into the middle of the deck (below right) or just under a tilted top card (above right). Either way, the card looks like it’s going into the middle of the deck from the vantage point of the spectator (left column). (Drawn by Jorge Otero-Millan)

Obviously not, but your visual system also tells you that your card is now occluded by the top of the deck. Your angle of perspective tells you that your card is being inserted. And your three-dimensional vision tells you that your card must be in the middle of the deck—about twenty-five cards down from the top card.

Of course this logic is all wrong when the back of the top card is tilted up during the second insertion attempt. Afterward, a very innocent motion of Vernon’s hand allows the tilted card to drop, and the gap is now closed. Your signed card is now in perfect position to be revealed by a double lift. Vernon tells you that your ambitious card has risen to the top, and there it is. Then he compounds your sense of awe by saying, “Let me show that to you again.” He double-lifts the two faceup cards back down, and then he removes the top card (which is not your signed card, though you think it is) and actually puts it into the middle of deck. And you know the rest. Your signed card is now on top.

Two normal depth perception cues—occlusion and perspective—have conspired to fool you. These processes are automatic and occur without your being aware of them, which is why the trick works. Remember we said your brain constructs reality? In this case, your visual system is telling you what is “real,” but it is a hapless victim in the hands of a skilled magician.

Occlusion refers to the fact that if one person is partly hiding behind another person, you naturally assume that the person who is not occluded is closer to you. The same goes for playing cards. This is a logical deduction made by your brain, done automatically and virtually instantaneously, without conscious thought.

Again, Vernon fools your visual system. Because you “see” your card being inserted into the middle of the deck, well then, the other cards must be on top. They are occluding your card, which must be fairly far down the deck.

Nobody knows where occlusion is computed in the brain, but it presumably happens high enough in your visual system that the relevant neurons encode individual shapes. Neurons that become active early in your visual pathway detect only small features of the world—edges, corners, curves. To put together an entire shape and see an object of interest (a person, a card), you need shape-selective neurons that combine the outputs from early feature detectors. Following this logic, you need an even later level of computation that can determine that a neuron’s favorite shape is being occluded. In this way, your visual system builds your depth perception like an automobile assembly line, one piece at a time, until you end up with a percept rich in depth.*

Also, Vernon is hacking into your brain’s drive to understand the world in perspective. Linear perspective rests on the fact that parallel lines, such as those in a railroad track, appear to converge in the distance (the Leaning Tower illusion in chapter 3 is based on this phenomenon). Your visual system interprets convergence as depth because it assumes parallel lines will remain parallel.

In Vernon’s card trick, size perspective comes into play. If two similar objects appear different in size, your visual system assumes the smaller one is more distant. Here, the signed card is slightly smaller on your retina, which means it must be farther away. It must be going into the middle of the deck, based on all the other clues you are seeing.

END OF SPOILER ALERT![]()

In the early 1970s, a new magic superstar swept onto the world stage. His name was Uri Geller—a tall, lanky Israeli with a Beatlesque mop of black hair, dark brows, and a penetrating stare. A charismatic stage performer, Geller could bend spoons, make watches stop or run faster, telepathically read hidden drawings, and otherwise blow people’s minds with his “supernatural powers.”

It was an era of unalloyed credulity.

Perhaps it was the drugs. When you place a windowpane of LSD on your tongue and watch the world transform into a Salvador Dalí landscape of radiant colors, shimmering geometric shapes, and morphing phantasmagoria while your sense of self dissolves—well, why can’t someone bend a spoon with his thoughts?

Perhaps it was Cold War paranoia. The CIA believed that the KGB had learned how to exploit extrasensory perception or remote viewing. Enemy spies could penetrate our secrets from halfway around the world using their telepathic powers. They could stop heartbeats from a distance (for an amusing look at his era, see the film Men Who Stare at Goats).

Perhaps it was one of those bizarre moments in history when unusually large numbers of otherwise rational people are seduced by magical thinking. New Age fads emblazoned the wonders of tarot cards, I Ching, Kirlian photography, crystal power, dowsing, astrology, and new approaches to personal development in harmony with planetary evolution.

Geller, at the forefront of this craze, was best known for his ability to bend spoons. “Isn’t it amazing?” he would marvel while holding a spoon at its neck, stroking it gently but rapidly with his index finger. Slowly, like an acrobat doing a languorous backbend, the spoon would bend, and bend, until it flopped at an askew angle. Spoon magic.

Millions of people were taken in by Geller’s act, until famed debunker of paranormal claims, James the Amaz!ng Randi, stepped up to throw a dose of cold water on Geller’s hot act.*

Geller said he performed his feats through supernatural powers. Randi came along and said that Geller’s feats were parlor tricks. He repeated them all, explaining how each was done—spoon bending, mind reading, stopping watches, dowsing, all of it. “Magical thinking is a slippery slope,” Randi says during his demonstrations. “Some-times it is harmless, other times quite dangerous. I expose people and their illusions for what they really are.”

For example, Randi explains that mentalists have been duplicating hidden drawings for years. A person draws something on a piece of paper and hides it, and the magician reveals what is on the drawing. Sometimes the magician turns his back and covers his eyes while the drawing is made. Randi wonders, “Why cover your eyes with your back turned?” He demonstrates. A small mirror concealed in the palm of his hand as it covers his eyes shows exactly what the person is drawing.

But despite Randi’s efforts to expose Geller as an illusionist, people kept believing. Even some scientists were taken in. In 1975 two researchers of paranormal psychology at the Stanford Research Institute, Russell Targ and Harold Puthoff, tested Geller and concluded he had performed successfully enough to warrant further serious study. They called it the “Geller effect.” Brain waves, they said, could affect pliable metal.

Danny Hillis, a renowned computer scientist and amateur magician, has an explanation for why scientists are particularly gullible to the Gellers of this world. “The better the scientist, the easier it is to fool them,” he says.

For example, Hillis once showed a magic trick to Richard Feyn-man, the Caltech physicist widely regarded as one of the most brilliant people who ever lived. “I’d do the trick and challenge him to figure it out. He’d go off for a day or two, think it through, and come back with the correct answer,” says Hillis. “Then I would repeat the trick using an entirely different method. And it drove him crazy. He never got the meta principle that I changed methods. This may be because of how scientists are trained to use the scientific method. You keep doing experiments until you find the answer. Nature is reliable. The idea that someone would switch methods just flummoxed him.”

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

Spoon bending can be done many ways. Here is how Tony taught us.*

He starts with three spoons and has someone pick one and examine it. He asks that person to put the spoon to his forehead—Tony demonstrates by putting a spoon to his own forehead—and tells the spectator to report when it starts feeling warm.

As Tony brings his spoon down from his little demonstration—while everyone’s attention is focused on the poor sucker holding a spoon to his forehead—Tony simultaneously bends both of his spoons ninety degrees at the neck.

This is the essence of spoon bending. The spoons are bent before the illusion is created. Magicians call it ratcheting. He bends the first one in his right hand with his thumb while holding the stem of the spoon in his fist. He simultaneously bends the second spoon at the neck by pushing the bowl against the inside of his inner right wrist. The maneuver is very clean and natural. It’s meant to look as though he is merely bringing the spoons together into his right hand. In any case, everybody’s attention is on the guy holding the spoon to his head. Meanwhile, Tony quickly transfers the now bent left-hand spoon into his right hand. He holds the two spoons between his right thumb and forefinger so that the bends of the two spoons touch each other knee to knee. It appears that he is holding two unbent spoons that are crossed at their necks.

Tony then shakes the spoons and “lets them wilt.” It looks as if the spoons become soft and floppy and the necks slowly bend. Actually, he is allowing the bent spoons to turn slowly between his fingers so that the bends are in the same direction, and the bowls eventually hang down. While the spoons are bending, Tony takes a brief break and retrieves the third spoon from the spectator with his free hand. He redirects everyone’s attention back to the bending spoons by saying that he is concentrating on them. His mind is bending them. Meanwhile, he surreptitiously bends the third spoon against his leg and then holds it so that only the stem is visible.

When the two “wilting” spoons are completely bent, Tony hands them back to the assisting spectator and says, “Now let’s try that again.” He holds the third spoon in both hands so that the stem is pointed vertically from behind his two interleaved hands. Neither the bowl of the spoon nor the now extant ninety-degree bend in its neck is visible. The audience assumes the spoon is still straight, since the spectator just inspected it.

The principle of good continuation helps you see the spoons are crossing when they are held by the magician (left), despite the fact that they are actually bent (right). (Drawn by Jorge Otero- Millan)

Tony begins to concentrate on the third spoon, and slowly, excruciatingly, without his applying any perceptible pressure, the stem of the spoon folds until its neck is bent toward him at a ninety-degree angle. Tony hands the bent spoon to the spectator, the audience applauds, and the routine is over.

A few critical psychological concepts help fool you into thinking the spoons must be straight when in fact they are already bent. The first is what visual scientists call amodal completion—the process by which an object that is occluded by a second object appears whole to you, even though it’s occluded. Imagine you are sitting in for one of our magic lessons here in Phoenix with Magic Tony. You’re at Cheuvront, munching on a Spanish cheese plate of manchego and queso de País, glass of Rioja in hand, and looking out across the vast Sonoran desert in between tricks. You notice a jackrabbit. It jumps three bounds and lands partially behind a massive four-armed saguaro cactus, with only its hindquarters sticking out, fuzzy white tail twitching. Does the rabbit still have a head? Of course it does. But how do you know? You can’t see it. How is it that your brain informs you about the shape of the hidden part of the rabbit behind the cactus? What if we were not discussing a rabbit but a blank rectangular surface that sticks out from one side of the cactus instead? In that case, you could not know from your experience how big the occluded part is, because rectangles, unlike rabbits, can have any size. But now imagine the rectangle poked out on both sides of the cactus so that you could see all four corners of the rectangle, but the middle remained occluded. Now, despite the fact that most of the surface is occluded, you have a very strong impression of how big the object is and what shape it takes—even though you can’t truly know what’s going on with the portion of the surface that’s behind the cactus.

In the case of the rabbit, your brain has mapped a three-dimensional biological model of a jackrabbit, and it makes perceptual guesses as to what the occluded part of the animal must look like. That’s very helpful, especially if you are hunting rabbits. And in the case of the rectangle, your brain can make certain perceptual guesses but not others, depending on how much information it has.

Tony took advantage of amodal completion when he pinched the two bent spoons between his thumb and forefingers. Because the stem from spoon number one lined up with the bowl of spoon number two, and vice versa, each spoon looked straight; amodal completion inappropriately completed both objects behind Tony’s fingers. Tony explains that this process obeys the law of “good continuation,” first codified by the German Gestalt psychologists of the turn of the century.

WHY GOOD CONTINUATION IS SO GREAT

![]()

Good continuation is the process by which your brain makes things seem whole based on sparse information. Amodal completion is one example of good continuation, but there are many others. We already mentioned filling in. The world is too large and too complex for you to see every item in it. When you look at a pebble-strewn beach or intricately woven Persian carpet, your brain is not resolving every pebble or every stitch of fabric. You don’t have enough cells in your retina for that. You see a small portion of beach or carpet and fill in the rest. Good continuation is so integral to a plethora of brain mechanisms that Tony thinks it is the most exploited principle in all of magic.

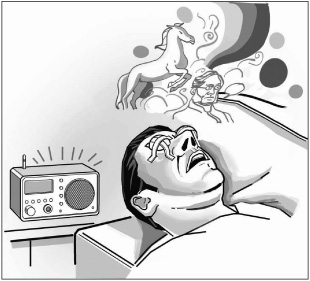

To see how clever your brain is at filling in, try the Ganzfeld procedure. (Ganzfeld is German for “the entire field.”) First, cut a Ping-Pong ball in half. Then tune your radio to static. Lie down, tape a half ball over each eye, and wait. Within minutes you will experience a flood of bizarre sensations. Polar bears cavort with elephants. Your long-deceased uncle comes into view. Whatever. Your brain cannot deal with zero sensory input, so it makes up its own reality. The point here is that your brain is constantly making up its own reality whether it receives actual reality-driven input from your senses or not. In the absence of sensory input, your brain’s own world making machinations keep on truckin’ nevertheless. That’s why solitary confinement is considered a punishment in our prison system. You might think that solitary confinement would be a relief from the dangers and unpleasantnesses of prison life. But it is just about the worst thing that you can do to prisoners, because they lose touch with reality. Many consider the practice a form of torture, and volumes have been written on the negative psychological effects of solitary confinement. Prisoners eventually report having hallucinations and other types of psychotic reactions. That is, they begin to believe the illusions.

How to hallucinate using Ping-Pong balls and a radio. (“Hack Your Brain,” republished with permission of Globe Newspaper Company, Inc., from a 2010 edition of the Boston Globe © copyright 2010)

Have you ever wondered how a magician saws a woman in half? The illusion is based on two things—a hollowed-out box and your brain’s desire for good continuation. When the woman lies down in the box, you see her head at one end and her feet at the other. Your brain tells you that she is supine and in one piece. Actually she is not lying down flat. The box is constructed so that the head protruding from one end and the feet sticking out the other end belong to two different women. The illusion is often enhanced by a painting of her supine body on the side of the box. How easily you are fooled.

Some mechanisms behind good continuation are becoming well understood. For example, in the visual system, good continuation depends on the orientation and spatial position of lines you may be looking at. When the relative position and orientation of two or more line segments are in alignment, you may see a contour. When two or more lines having similar orientations are positioned close together with their ends aligned, you may notice that individual segments are more visually salient: they pop out against the background. But if the separation between segments, or the differences in their orientations, is too great, good continuation fails and the segments are more difficult to discriminate from the background.

Charles Gilbert and colleagues in his laboratory at the Rockefeller University have found a physical basis for good continuation in the visual system. Recall that neurons in your primary visual cortex are tuned to specific orientations—they prefer, say, horizontal line segments or vertical ones. Such specialized neurons are found in different parts of the primary visual cortex so that your brain can integrate information well beyond the boundaries of single neurons. It turns out that neurons with similar attributes are connected via horizontal fibers that travel long distances in the primary visual cortex. Your mind’s eye can “see” the rabbit behind the cactus because of the long-range connections between similar types of neurons in the cortex. The same processes could play a role in more cognitive types of visual perception, which we will discuss more fully in later chapters.

A second concept behind the spoon illusion has been documented. When spoons are shaken just so, they suddenly appear floppy. The illusion occurs because your visual system has two different mechanisms for seeing lines: one that specializes in edges and another that specializes in the ends of lines. To detect the edge of a line, you rely on neurons in your primary visual cortex. To localize the ends of a line, however, you call on endstopped cells that are tuned to respond to the ends of long contours.

Some orientation and endstopped neurons respond especially well to moving stimuli, such as the stem of a shaking spoon. But the timing of their responses is different. Your brain perceives the orientation of lines faster than the ends of lines. Thus the stem of a shaking spoon appears to move before the ends move—giving rise to the illusion that the spoon is bending.

END OF SPOILER ALERT![]()

As romantic as it may be to conclude that thoughts can bend spoons or levitate tables or that psychic powers, clairvoyance, and mind over matter are real phenomena, the consequences of such beliefs can be painful, or at least embarrassing. When Susana was about eight years old, she got it in her head that she should be able to walk through barriers by sheer mental effort. The heavy wrought iron gates of her grandparents’ apartment building in Santander, Spain, seemed ideal for the experiment. When the adults were down for siesta, she sneaked out and ran down the three flights of stairs leading to the entrance of the building. She was determined and she ran at full speed, headfirst. Surprisingly, the wrought iron didn’t budge, as evidenced by the small scar she still has on her left temple. It took more than a decade for her to confess to her family that she hadn’t accidentally tripped that day.

Some performers believe they have genuine gifts. Others are clearly con-men who take advantage of unsuspecting or desperate customers who honestly believe in psychic abilities. Psychics, faith healers or mediums appear to defy the laws of nature—but part of this book is about discovering how they really work.