APPENDIX A—METHYLATION

Introduction

Methylation is a biochemical process of extraordinary importance in human functioning. It may be defined as the addition of a methyl group (CH3) to an atom or molecule. Methyl groups participate in dozens of chemical reactions in the body and brain that are essential to physical and mental health. In addition, methylation status is a major factor in a person’s personality and traits. For example, undermethylation is associated with perfectionism, strong will, high accomplishment, OCD tendencies, and seasonal allergies. Typical features of overmethylation include excellent socialization skills, many friendships, non-competitiveness, artistic or musical interests, chemical and food sensitivities, and a tendency for high anxiety. Unfortunately methyl imbalances can also contribute to serious disorders that afflict millions of people. The new field of epigenetics is revolutionizing our understanding of cancer, heart disease, mental illness, and autism, and the most dominant chemical factor in epigenetics is methylation. Many disorders previously believed to be genetic and resistant to treatment are actually epigenetic and very treatable. Approaches for normalizing methylation are likely to be a primary focus of medical research over the next 20 years.

Prevalence of Methylation Disorders

Based on my detabase of 30,000 persons, about 70% of the population exhibits normal methylation, 22% are undermethylated, and 8% are overmethylated. However, more than two-thirds of persons diagnosed with a behavior or mental disorder exhibit a methylation imbalance. A person’s methyl status is established during the first few months of in-utero development and this condition tends to persist throughout life.

There are four primary types of methylation reactions that are essential to life:

Methylation of atoms: An important chemical reaction in humans is methylation of metals. For example, methylation of mercury or other toxic metals impacts the availability of the toxin to the brain and other organs, and influences the rate of excretion from the body.

Methylation of atoms: An important chemical reaction in humans is methylation of metals. For example, methylation of mercury or other toxic metals impacts the availability of the toxin to the brain and other organs, and influences the rate of excretion from the body.

Methylation of Molecules: There are hundreds of important biochemical reactions in which a methyl group is donated to a molecule. In most cases, the reaction requires a methyltransferase enzyme. Methylation of amino acids is an important mechanism for producing a wide variety of proteins in the body.

Methylation of Molecules: There are hundreds of important biochemical reactions in which a methyl group is donated to a molecule. In most cases, the reaction requires a methyltransferase enzyme. Methylation of amino acids is an important mechanism for producing a wide variety of proteins in the body.

DNA Methylation: Gene expression (protein production) within cells is regulated by methylation at certain cytosine sites along the DNA double-helix molecule. This reaction primarily occurs at CpG sites where a guanine residue is adjacent to cytosine … connected only by a phosphorous atom. With few exceptions, CpG methylation inhibits gene expression. The relative degree of CpG methylation can determine the rate of protein synthesis in individual cells and tissues.

DNA Methylation: Gene expression (protein production) within cells is regulated by methylation at certain cytosine sites along the DNA double-helix molecule. This reaction primarily occurs at CpG sites where a guanine residue is adjacent to cytosine … connected only by a phosphorous atom. With few exceptions, CpG methylation inhibits gene expression. The relative degree of CpG methylation can determine the rate of protein synthesis in individual cells and tissues.

Methylation of Histone Proteins: Another process for regulating gene expression involves methylation of acetylation of histones, the tiny protein aggregates that serve as structural supports for fragile DNA strands in the nucleus of every cell. Histone methylation usually occurs at lysine or arginine sites and results in compaction of the DNA, thereby restricting the access of transcription factor molecules necessary for gene expression. However, there are exceptions to this rule in which methylation at certain histone sites can promote gene expression.

Methylation of Histone Proteins: Another process for regulating gene expression involves methylation of acetylation of histones, the tiny protein aggregates that serve as structural supports for fragile DNA strands in the nucleus of every cell. Histone methylation usually occurs at lysine or arginine sites and results in compaction of the DNA, thereby restricting the access of transcription factor molecules necessary for gene expression. However, there are exceptions to this rule in which methylation at certain histone sites can promote gene expression.

Methylation Lab Testing

A person’s methyl status is affected by diet and environment but genetics is usually the dominant factor. Most methyl groups originate from dietary methionine that converts to s-adenosylmethionine, (SAMe), a relatively unstable molecule that donates methyl groups for dozens of essential methylation reactions. The production and regulation of SAMe is achieved by a complex “one-carbon cycle” or “methylation cycle” of biochemical reactions that depends on numerous enzymes that are prone to genetic mutations. Enzymes are formed in the body by genetic expression and many of them are extremely large molecules. For example the important MTHFR enzyme contains more than 500 amino acids and has a molecular weight exceeding 77,000. Genetic mutations usually take centuries to develop and statistically are most likely to occur in very large molecules. The most common mutations are “single nucleotide polymorphisms” or SNPs which can cause one of the enzyme’s amino acids to be in the wrong place. For example, a cysteine may be where an arginine is supposed to reside. While many SNPs do not alter the enzyme’s function, others such as certain MTHFR mutations can markedly reduce the priduction of SAMe and result in an undermethylated condition. To complicate matters, overmethylation can result from inefficient utilization of SAMe, especially in the creatine pathway. Normally, more than 70% of SAMe produced in the one-carbon cycle is consumed in the production of creatine. SNP mutations in this process can result in an overabundance of unused SAMe throughout the body.

Since there are SNPs that tend to reduce methylation and others that tend to increase methylation, a patient’s overall methyl status depends on the overall combined impact of these SNPs. The popular genetic tests for MTHFR, MS, and other SNPs provide interesting information, but are qualitative in nature and limited in their ability to accurately determine overall methyl status. SNPs that reduce SAMe production are often counterbalanced by SNPs that tend toward overmethylation. Diagnosis of overall methyl status is very important in clinical treatment of mental disorders. Two lab assays that directly measure the net effect of the competing SNPs are SAMe/SAH ratio and whole-blood histamine.

The One-Carbon Cycle

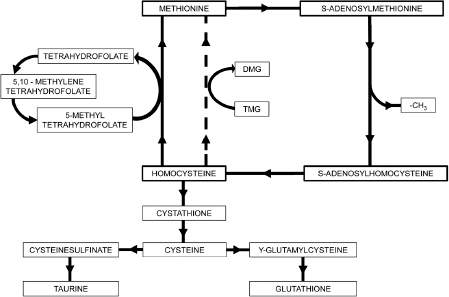

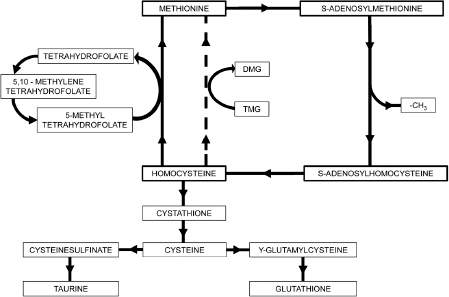

A versatile methyl donor is SAMe, a molecule found in each of the trillions of cells in the human body. SAMe is produced from methionine, an amino acid present in dietary protein. A stable SAMe concentration is essential to normal embryonic development and a multitude of chemical processes throughout life. An important means for regulating SAMe levels is the one-carbon cycle, also known as the SAM cycle or the methylation cycle. This process consists of a series of chemical reactions that produce, consume, and regenerate SAMe. A schematic diagram of the one-carbon cycle is presented in Figure A-1. This biochemical cycle consists of four primary steps:

Figure A-1. Methylation Cycle

Step 1: Dietary methionine combines with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to form SAMe. ATP is a high-energy molecule that drives the reaction with the assistance of magnesium. SAMe is a molecule that readily gives up its methyl group.

Step 2: After giving its methyl group away, SAMe is transformed into SAH (S-adenosylhomocysteine), a molecule that can be recycled to form methionine. However, if SAH builds up to excessive levels, methylation by SAMe slows down. Therefore, it is necessary for SAH to be efficiently removed by chemical reaction to enable proper methylation capability. The gold standard test for methylation status is the ratio of SAMe to SAH.

Step 3: In healthy persons, SAH is efficiently converted to homocysteine (Hcy) and proper methylation levels are maintained. The reaction involves removal of the adenosine group, assisted by an enzyme. Adenosine, in turn, is removed from the scene by adenosine deaminase (ADA), a zinc-containing enzyme. There is considerable evidence that the ADA enzyme reaction is abnormally weak in autism and other disorders.

Step 4: Part of the homocysteine is recycled to methionine, with the remainder converted to cystathionine. Both of these pathways are essential to good health: (a) recycling to methionine assists in maintenance of SAMe levels, and (b) the cystathionine pathway is a primary source of cysteine, glutathione, and other valuable antioxidants. The fraction of Hcy converted to methionine (or alternatively to cystathionine) depends on the level of oxidative stress present. It’s interesting to note that high oxidative stress can cause undermethylation and also that undermethylation can cause excessive oxidative stress. The presence of either imbalance can cause the other. Recycling of Hcy to methionine can be achieved by reactions with 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MeTHF) and vitamin B-12. The 5-MeTHF supplies a methyl group to form methyl-B-12, which then reacts with Hcy to produce recycled methionine. This reaction is enabled by the methionine synthase enzyme. Hcy can also convert to methionine by direct reaction with trimethylglycine (TMG), a molecule that transfers a methyl group to Hcy to form methionine and dimethylglycine (DMG).

Methylation of atoms: An important chemical reaction in humans is methylation of metals. For example, methylation of mercury or other toxic metals impacts the availability of the toxin to the brain and other organs, and influences the rate of excretion from the body.

Methylation of atoms: An important chemical reaction in humans is methylation of metals. For example, methylation of mercury or other toxic metals impacts the availability of the toxin to the brain and other organs, and influences the rate of excretion from the body.