Sun Zi was an extraordinary thinker, still very influential. As a strategist he shares supremacy with just one other writer: Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), author of On War (1832). Like Clausewitz, Sun Zi is unfortunately most familiar at second hand, through a handful of quotations that lack context, for like Clausewitz, he, too, is rarely read in his entirety, with real care. One reason for this is the great difficulty of translating either of these works into lucid English in a way that is true to the texts. Vom Kriege is difficult enough. Not until 1976 did a first-rate translation appear, by Michael Howard and Peter Paret.1

The problems faced by the translator of Sun Zi—textually, philologically, and in every other respect (save length)—are, however, orders of magnitude greater. Many fine scholars have attempted the task, and several excellent versions are already published. This one, however, stands out above the others. I am deeply honored to be invited to offer a foreword to this English version of Sun Zi, by my colleague Victor Mair, which I am confident will become the standard, both because of the deep understanding of the text that it manifests and because of its great clarity and readability.

To begin at the beginning: The title of Sun Zi’s text, bingfa  is usually put into English as “the art of war,” which suggests a closeness of theme to Clausewtiz’s Vom Kriege, which unquestionably means “on war.” But bing in Chinese usually means soldier, and Sun Zi, as Mair makes clear in his notes and as is evident from the text, is almost entirely concerned with military methods that can lead to victory, rather than with war as a general phenomenon. In his first chapter Sun Zi says a certain amount about the importance of war to the state and the perils of waging it unsuccessfully. But he is not concerned, as Clausewitz is, to isolate the philosophical essence of war, in the manner that German philosophers among his contemporaries did, in their studies of history, aesthetics, morals, or similar topics.

is usually put into English as “the art of war,” which suggests a closeness of theme to Clausewtiz’s Vom Kriege, which unquestionably means “on war.” But bing in Chinese usually means soldier, and Sun Zi, as Mair makes clear in his notes and as is evident from the text, is almost entirely concerned with military methods that can lead to victory, rather than with war as a general phenomenon. In his first chapter Sun Zi says a certain amount about the importance of war to the state and the perils of waging it unsuccessfully. But he is not concerned, as Clausewitz is, to isolate the philosophical essence of war, in the manner that German philosophers among his contemporaries did, in their studies of history, aesthetics, morals, or similar topics.

Clausewitz has a good deal to say about the operational and tactical issues involved in winning a war, and comparing Sun Zi to him at these points is very useful. But no explicit counterpart exists in Sun Zi to the carefully articulated philosophical framework about the fundamental nature of war that Clausewitz develops. One can, however, deduce Sun Zi’s views on some of these issues.

Consider the question of the nature of war itself. Clausewitz had “first encountered war in 1793 as a twelve-year-old lance corporal” fighting the French, a task to which he was devoted until the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo thirty-two years later.2 The Napoleonic Wars, though punctuated by truces and the forming and re-forming of coalitions, were essentially continuous and protracted over decades. They provided vivid lessons in the way that no single battle, no matter how decisive it might seem—either Austerlitz or Trafalgar, both in 1805, for example—seemed ever to be genuinely conclusive. They showed how the use of force elicited counterforce, and how the scale of that force might be driven up by this reciprocal action, in what today is called “escalation.” The central importance of politics and the interaction between politics and the use of force was also clear in the Napoleonic Wars, particularly with respect to truces, the formation and maintenance of coalitions, and, in the final years, the issue of war aims with respect to Napoleon—could he be allowed to stay on as emperor in France, or was “unconditional surrender” (a term not yet in use) the goal?

From his experience of prolonged, escalating, and politically determined war, Clausewitz drew some of his most famous conclusions. What is war, in essence? His reply: “War is an act of force, and there is no logical limit to the application of that force. Each side, therefore, compels its opponent to follow suit; a reciprocal action is started which must lead, in theory, to extremes.”3 “War does not consist of a single short blow”;4 “In war the result is never final”;5 and, most famously, though the phrase can only be understood properly within the context that Clausewitz provides, “War is not merely an act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse, carried on with other means. What remains peculiar to war is simply the peculiar nature of its means.”6

Clausewitz’s fundamental concern is that unless they are firmly controlled by a political authority outside the military and having a fixed end in mind, the means by which war is waged—the application and counterapplication of force—will simply by their own interaction drive or escalate the conflict to a level of intensiveness and destruction that was not desired by either combatant and is not in either of their interests.

In Clausewitz’s time, the ability to wage long, difficult, and ultimately decisive campaigns was all important. Troops and money could be found by the nation-states of late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Europe. By contrast, in the China of Sun Zi’s time, nothing like the decades of conflict with Napoleon was possible. Simply to raise a single army taxed any state to the limit. If it was to have any political usefulness, violence therefore had to be concentrated in a handful of encounters, with rapid decision the goal.

This fact goes some way toward explaining the differences between the ways the two authors look at war in general. For Clausewitz it is above all a test of force. For Sun Zi it is more a psychological contest, with force having a far more limited role. For Clausewitz, war and fighting are, by their very nature, protracted. Sun Zi’s ideal is to avoid fighting altogether. Political objectives and the ways they are affected by the successes and failures of combat are for Clausewitz of utmost importance. Sun Zi assumes a straightforward political goal. After this goal has been conveyed to him by the ruler, the general does what is appropriate until he wins. The reciprocal interaction between politics and fighting, upon which Clausewitz lays such stress, is virtually absent in Sun Zi. “The peculiar nature of its means” is what distinguishes war from other forms of political activity according to Clausewitz, who discusses much about war other than its means. Methods, however, “Soldierly Methods,” are Sun Zi’s primary and almost sole concern.

For both authors, the goal of war is, as Clausewitz states it, “to compel the enemy to do our will.”7 But how is this to be done? Clausewitz assumes the task will be accomplished by “an act of force.”8 The use of force is, after all, the feature that Clausewitz takes as distinguishing war from other state activities, such as diplomacy. But Sun Zi, concerned not with war so much as with the methods best employed by soldiers, seeks to minimize the use of force, rather as did the mercenary leaders, the condottieri of the European renaissance.

Probably the most celebrated and often quoted line from Sun Zi is the one that Professor Mair renders as: “Being victorious a hundred times in a hundred battles is not the most excellent approach. Causing the enemy forces to submit without a battle is the most excellent approach.”9 The vision of victory without fighting is fundamental to Sun Zi’s entire argument. I will turn in a moment to considering how he seeks to achieve it. But his search for victory without what Clausewitz regularly calls “the maximum use of force”10 is evident simply from the low frequency with which Sun Zi invokes the concept. The Chinese word li,  meaning “force,” is used only nine times in all thirteen chapters of Sun Zi, with some of these occurrences being negative in implication, in fact, warnings against the misuse of force. The corresponding German word, Gewalt, by contrast occurs eight times in just the two paragraphs in which Clausewitz defines war.11

meaning “force,” is used only nine times in all thirteen chapters of Sun Zi, with some of these occurrences being negative in implication, in fact, warnings against the misuse of force. The corresponding German word, Gewalt, by contrast occurs eight times in just the two paragraphs in which Clausewitz defines war.11

Clausewitz could not be clearer in his insistence that fighting is at the center of warfare. As he puts it in a celebrated passage:

We are not interested in generals who win victories without bloodshed. The fact that slaughter is a horrifying spectacle must make us take war more seriously, but not provide an excuse for gradually blunting our swords in the name of humanity. Sooner or later someone will come along with a sharp sword and hack off our arms.12

What, then, is Clausewitz’s soldierly method? It is, to be sure, to wage war ferociously, exerting maximum force, but in a carefully considered way. But the mind is key to how force is to be applied. “The maximum use of force is in no way incompatible with the simultaneous use of the intellect.”13 As the shape of the conflict becomes clear, the perceptive general will be able to identify what Clausewitz calls the “center of gravity [Schwerpunkt].” As he explains, “One must keep the dominant characteristics of both belligerents in mind. Out of those characteristics a certain center of gravity develops, the hub of all power and movement, on which everything depends. That is the point at which all our energies should be directed.”14 This center of gravity is likely to be military: the army of the opposing commander, for example. But it need not be such. Clausewitz is fully aware that some other aspect of a society at war may be all important and potentially decisive.

For Alexander, Gustavus Adolphus, Charles XII, and Frederick the Great, the center of gravity was their army. If the army had been destroyed, they would all have gone down in history as failures. In countries subject to domestic strife, the center of gravity is generally the capital. In small countries that rely on large ones, it is usually the army of their protector. Among alliances, it lies in the community of interest, and in popular uprisings it is the personalities of the leaders and public opinion. It is against these that our energies should be directed. If the enemy is thrown off balance, he must not be given time to recover. Blow after blow must be aimed in the same direction: the victor, in other words, must strike with all his strength, and not just against a fraction of the enemy’s. Not by taking things the easy way—using superior strength to filch some province, preferring the security of this minor conquest to great success—but by constantly seeking out the center of his power, and by daring all to win all, will one really defeat the enemy.15

Sun Zi adopts a different premise. Far from finding the center of gravity in the battle, he finds it in the psychology of the adversary. His goal is to unnerve his opponents, to demoralize them, to mislead them, and to outmaneuver and threaten them, in such a way that their social cohesion breaks down and their rulers and military find themselves in disorder and chaos. If force is indispensable to doing this then he advocates its careful use. But he does not look to force as a first resort.

The chaos and disorder Sun Zi seeks to create may be a physical state resulting from a decisive military defeat. But its sources are psychological. A useful way of understanding this is to say that while Clausewitz seeks to take a state that is independent and defiant, and inflict upon it physical and moral defeat, Sun Zi seeks to undermine the orderliness of his opponent, the situation expressed by the character zhi,  in which the state is being stably ruled, and render it luan

in which the state is being stably ruled, and render it luan  which is to say, chaotic. The Chinese populations for control of which the kings of the warring states contended had no nationalistic passions of the sort that enflamed the Napoleonic Wars. Provided rule was not too onerous, they cared no more about which kingly clan was in charge than did German farmers in the Holy Roman Empire about which of a changeable constellation of nobles and ecclesiastical authorities had sovereignty over them. With Sun Zi we are in a world that corresponds to the European world of dynasties, in which kings fought with specialized armies and ordinary people cared little about the outcome of war. Clausewitz writes about quite a different world, most importantly, one in which national identities are congealing and national passions have been released.

which is to say, chaotic. The Chinese populations for control of which the kings of the warring states contended had no nationalistic passions of the sort that enflamed the Napoleonic Wars. Provided rule was not too onerous, they cared no more about which kingly clan was in charge than did German farmers in the Holy Roman Empire about which of a changeable constellation of nobles and ecclesiastical authorities had sovereignty over them. With Sun Zi we are in a world that corresponds to the European world of dynasties, in which kings fought with specialized armies and ordinary people cared little about the outcome of war. Clausewitz writes about quite a different world, most importantly, one in which national identities are congealing and national passions have been released.

For Sun Zi, then, the center of gravity is not the enemy’s army or his capital. It is the enemy’s mind and the morale of his soldiers. How, we may ask, does Sun Zi suggest we attack such an intangible-seeming a target?

Sun Zi’s method can be summed up by four characters, in sequence. These are quan,  which we may call “assessment” (the word’s origin is “to weigh”); shi,

which we may call “assessment” (the word’s origin is “to weigh”); shi,  which should be understood as all of the factors and tendencies bearing on a possible battle, and which Mair translates marvelously as “configuration”; then ji,

which should be understood as all of the factors and tendencies bearing on a possible battle, and which Mair translates marvelously as “configuration”; then ji,  which indicates the moment at which the “configuration” of the various influences is most propitious for action; and finally mou,

which indicates the moment at which the “configuration” of the various influences is most propitious for action; and finally mou,  which is often translated by the little-used English word “stratagem,” a term that suggests not simply an “operational plan” as it would be called today, but in particular an operational plan that extracts maximum value from psychological as opposed to material factors. An ambush is a stratagem; a frontal attack is simply an operational plan.

which is often translated by the little-used English word “stratagem,” a term that suggests not simply an “operational plan” as it would be called today, but in particular an operational plan that extracts maximum value from psychological as opposed to material factors. An ambush is a stratagem; a frontal attack is simply an operational plan.

Clausewitz would probably agree with all of this, except for the implication that if properly executed—indeed, if properly threatened but not executed—the method Sun Zi proposes can transform order or zhi into chaos or luan simply by psychological dislocation.

Certainly the great Prussian writer would agree about the tremendous importance of judgment, quan. This is apparent in the stress he lays on the quality and independent creativity of the commander, to whom he accords every bit as much importance as does Sun Zi. For it is from the mind of the commander that victory comes. Material balances, morale, logistics, and so forth are all important. But only a commander of genius can develop a winning strategy or stratagem. Both authors, therefore, differ very much from writers who see warfare as a test of national resources, technology, and resolve. War is above all a matter of solving complex intellectual problems, many of which have no simple formula or algorithm. Sun Zi would agree, I think, with Clausewitz that:

The man responsible for evaluating the whole must bring to his task the quality of intuition that perceives the truth at every point…. Bonaparte rightly said in this connection that many of the decisions faced by the commander-in-chief resemble mathematical problems worthy of the gifts of a Newton or an Euler.

What this task requires in the way of higher intellectual gift s is a sense of unity and a power of judgment raised to a marvelous pitch of vision, which easily grasps and dismisses a thousand remote possibilities which an ordinary mind would labor to identify and wear itself out in so doing.16

Where the two men would disagree, I think, is about the means that the commander of genius will employ. How does Sun Zi envision decisive psychological dislocation as being achieved absent the use of force?

In a famous passage, Sun Zi writes that all war is deception, gui dao.  When Westerners think of deception their minds will likely turn to dummy tanks and guns or, at the best, to the successful allied effort to mislead the Germans as to where the D-Day landing would occur. No Western strategist, and certainly not Clausewitz, would ever put deception at the heart of military method. Yet Sun Zi does this. The fact is clear linguistically. In Chinese philosophy, the moral way, or dao,

When Westerners think of deception their minds will likely turn to dummy tanks and guns or, at the best, to the successful allied effort to mislead the Germans as to where the D-Day landing would occur. No Western strategist, and certainly not Clausewitz, would ever put deception at the heart of military method. Yet Sun Zi does this. The fact is clear linguistically. In Chinese philosophy, the moral way, or dao,  is what gives rulers their legitimacy and society its cohesion. Sun Zi makes this clear at the very beginning of his treatise. The centrality of the concept in general political thought means that its manipulation must also be central. To twist the dao itself and create a deceptive dao is to subvert the foundation upon which all society and human activity is believed, by Chinese philosophers, to rest. Doing so is therefore far more grave and potentially far more powerful than any mere “deception” would be in the West.

is what gives rulers their legitimacy and society its cohesion. Sun Zi makes this clear at the very beginning of his treatise. The centrality of the concept in general political thought means that its manipulation must also be central. To twist the dao itself and create a deceptive dao is to subvert the foundation upon which all society and human activity is believed, by Chinese philosophers, to rest. Doing so is therefore far more grave and potentially far more powerful than any mere “deception” would be in the West.

Western writers and strategists have understood the importance of psychological dimensions in warfare. Consider the climax of the Battle of Waterloo. As John Keegan describes it:

Napoleon was heavily engaged on two fronts and threatened with encirclement by the advancing Prussians. He had only one group of soldiers left with which to break the closing ring and swing the advantage back to himself. This group was the infantry of the Imperial Guard. At about seven it left its position…. The British battalions on the crest fired volleys into its front and flank … heavy and unexpected [emphasis supplied]—and, to their surprise, saw the Guard turn and disappear into the smoke from which it had emerged. On the Duke of Wellington’s signal, the whole line advanced…. Napoleon had been beaten.17

The sudden turn of the tide caused by the withdrawal of La Garde fits into a Western pattern of warfare that has existed since the hoplite battles in Greek times, in which the final phase of “collapse” or trope (τροπη) is followed by “confusion, misdirection, and mob violence.”18 At Waterloo, just why the Imperial Guard pulled back is impossible to say, but Keegan and others stress psychological factors.19

But as we will see, Western methods of war have evolved away from psychological means toward ever greater applications of men, technology, and materiel. At Waterloo the retreat of the Guards took all by surprise. Chinese operations, by contrast, invariably have a strong psychological aspect even today. Perhaps the best example is the collapse of the Eighth Army in Korea, which led to the longest retreat in American military history and introduced the phrase “bug out” to our language. This began in late November 1950, as American forces approached the Yalu River, when Chinese units that had been secretly deployed outflanked and ambushed the American Second Division at the disastrous battle of Kunuri beginning November 26. In the period that followed, morale collapsed, and most of the Americans fled in disorder.20 Chaos and disorder induced by psychological mechanisms triggered by military facts have a long history in both China and the West.

In the Bible we learn that the Philistines were thrown into disorder when they realized that no less than Yahweh himself was assisting the Israelites in I Samuel 7:10. “The Philistines drew near to battle against Israel: but the LORD thundered with a great thunder on that day upon the Philistines and discomfited them; and they were smitten before Israel.” Here “discomfited” is the Hebrew “wayehummem [ ],” meaning “to throw into confusion and panic” and is used especially with Yahweh as subject and an enemy as object within a holy war context. The associated noun mehumah [

],” meaning “to throw into confusion and panic” and is used especially with Yahweh as subject and an enemy as object within a holy war context. The associated noun mehumah [ ] denotes “the divine consternation or panic” produced by Yahweh’s self-manifestation, through storms.21

] denotes “the divine consternation or panic” produced by Yahweh’s self-manifestation, through storms.21

The Canaanite god Ba‘al was also well known “as the divine warrior and thunderer.” According to Frank Cross, one pattern of such appearance is “the march of the Divine Warrior to battle, bearing his terrible weapons, the thunder-bolt and the winds. He drives his fiery cloud-chariot against his enemy. His wrath is reflected in all nature. Mountains shatter; the heavens collapse at his glance. A terrible slaughter is appointed.”22

As Jeffrey Tigay points out (see note 21), a similar notion of decisive confusion in war is conveyed by the Greek kudoimos (κυδοιμοσ), as in the Iliad, when Athena intervenes:

There he [Achilles] stood, and shouted, and from her place Pallas Athene

Gave cry, and drove an endless terror [i.e., confusion] upon the Trojans.23

Or the comparable phenomenon in the Odyssey, as the long-absent hero slays his wife’s suitors:

And now Athene waved the aegis [shield] that blights humanity,

from high aloft on the roof, and all their wits were bewildered;

and they stampeded about the hall, like a herd of cattle

set upon and driven wild by the darting horsefly.24

Tian,  the Chinese “Heaven,” lacked the anthropomorphic features of the Yahweh or Ba‘al or Pallas Athena, but it could intervene in battle, through the power of virtue, or de

the Chinese “Heaven,” lacked the anthropomorphic features of the Yahweh or Ba‘al or Pallas Athena, but it could intervene in battle, through the power of virtue, or de

For Confucian thinkers, a ruler who followed the way of the true king (wang dao  ) would never need to use force. His moral example would be enough to give order to his realm. The proof text is the classical account of how the Zhou dynasty overthrew the corrupt Shang at the semilegendary battle of the Wilderness of Mu [Muye]

) would never need to use force. His moral example would be enough to give order to his realm. The proof text is the classical account of how the Zhou dynasty overthrew the corrupt Shang at the semilegendary battle of the Wilderness of Mu [Muye]  in 1045 B.C., which Confucian philosophers took as the prototype of proper warfare. According to the Classic of Documents, the Shang troops “would offer no opposition to our army. Those in front inverted their spears and attacked those behind them, till they fled, and the blood flowed.” The victory was achieved by the working of Zhou virtue on the Shang forces. The empire was restored in the same way: King Wu of Zhou “had only to let his robes fall down, and fold his hands, and the empire was orderly ruled.”25

in 1045 B.C., which Confucian philosophers took as the prototype of proper warfare. According to the Classic of Documents, the Shang troops “would offer no opposition to our army. Those in front inverted their spears and attacked those behind them, till they fled, and the blood flowed.” The victory was achieved by the working of Zhou virtue on the Shang forces. The empire was restored in the same way: King Wu of Zhou “had only to let his robes fall down, and fold his hands, and the empire was orderly ruled.”25

Sun Zi, to be sure, does not rely upon Heaven to produce the psychological dislocation that brings the enemy down. Nor does he look for repeated military blows to produce it. Instead, Sun Zi assumes that he will possess near-perfect knowledge of the enemy’s dispositions—intelligence dominance in today’s parlance—as well as secret agents in the enemy’s country and even his court, ready to rise up when the signal is given. He will be able to deceive his adversary and move unobserved. (His own dispositions, however, will be utterly opaque to the enemy.) When the enemy discovers the hopelessness of its situation, its commander will find himself totally bewildered, and its troops will panic. Divine intervention is not necessary for this. “Betrayal” is enough, as in the French cry, “Nous sommes trahis! [We are betrayed!],” often heard when they have, in fact, simply been outmaneuvered, or the simple “We’re buggin’ out—We’re movin’ on!” of the Second Division’s “Bugout Boogie.”26

Clausewitz understands psychological factors, but he does not believe they can reliably stand alone or play a greater role in battle than actual fighting. As for intelligence, on the basis of his many years as a soldier, Clausewitz simply discounts the possibility of ever achieving such dominance as Sun Zi takes for granted. Clausewitz is dismissive about intelligence in general:

The textbooks agree, of course, that we should only believe reliable intelligence, and should never cease to be suspicious, but what is the use of such feeble maxims? They belong to that wisdom which for want of anything better scribblers of systems and compendia resort to when they run out of ideas. Many intelligence reports in war are contradictory, even more are false, and most are uncertain.27

Here in fact is the basic difference between Clausewitz and Sun Zi. Perhaps because he lives in a culturally uniform world having very limited resources, Sun Zi concentrates on making the most of nonmaterial cultural commonalities (which render deception and espionage easier) and minimizing the expenditure of materiel. Clausewitz lives in a world where nation-states are very different, espionage and deception difficult, and materiel relatively more abundant. In any case, Sun Zi is above all concerned with maximizing the efficacy of any military operation while limiting its duration. Indeed, the duration of his ideal military operation, which succeeds without fighting, is zero. Clausewitz, by contrast, seeks to maximize the cumulative effectiveness of force applied over time, against the enemy’s center of gravity.

What we have here are two different approaches to the problem of the great costliness of war. In the West conflicts were often over matters difficult to resolve, such as religious belief or national affiliation, and even the most skillful military tactics—Napoleon’s for example—could not avoid immense costs. So the state was transformed in the West to support such war: serfdom was abolished; taxation and national borrowing greatly expanded; armies were reformed and made professional; national leadership was entrenched and legitimized by mass participation; and so forth. In China, however, the goal was usually control of a people left unchanged by the conflict, and the attempt was to transform war so as to make it less costly and more rapidly decisive. This is what the Chinese military classics are about.

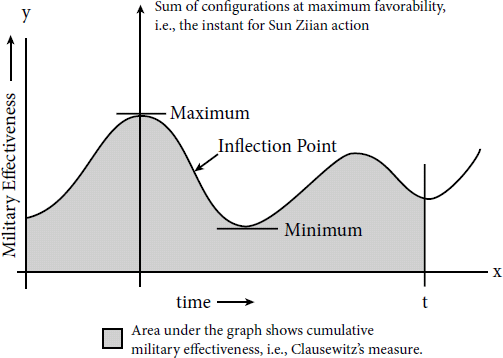

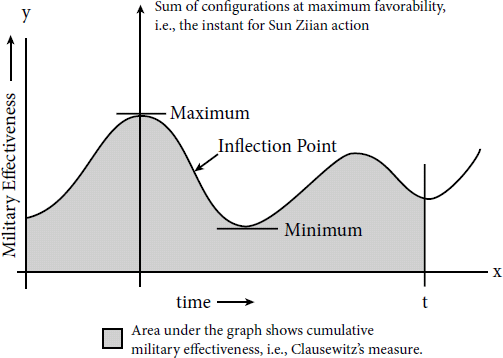

Consider Sun Zi’s idea of “configuration.” What this means is that, over time, day to day or hour to hour, the potential effectiveness of a military operation will rise and fall as the factors contributing to configuration change. Sun Zi has only a limited amount of force at his disposal. Once it has fought, his army cannot be replenished to fight again. So configuration must be assessed with great precision, and the moment to expend force must be chosen with care. The natural and other forces associated with war are far more powerful than any military factors. Compared to the number of opportunities presented, Sun Zi’s general will fight only rarely.

Clausewitz, by contrast, expects war to go on until one side or the other is broken: materially, strategically, psychologically, or all three. Many factors may slow war down. At some point only the will of the commander remains. But persistence in fighting, provided strategy and tactics are sound, is likely to prevail—but cumulatively, not instantaneously.

Now suppose that we think about this using the language of mathematics. Suppose we graph the potential effectiveness of a military operation, expressing it as y = f(x) where x is time and y is the effectiveness of a military operation, with f(x) being a measurement or a function that processes all the factors bearing on “configuration” and their interactions at time x.

In other words, if c represents the weighted value of one or another dimension of “configuration” at time x, f(x) may be thought of as Σ c1 + c2 + … cn where n is the number of variables being considered. What aspects of this curve will be of interest to Sun Zi? The answer, I think, is that Sun Zi will be most interested in the points where the curve changes direction or reaches a maximum or minimum, that is to say, in f ′ and f ″, the first and second derivatives of the function.

What will Clausewitz be interested in? For him, military effort is continuous, so he will want to look at the sum total, the cumulation of the function, over a period of time, that is, the area under the curve. In mathematical terms, if x is time, it is the integral from x = 0 to x = t of the function, i.e., ∫0tf (x).

Of course, it would be absurd to attempt to quantify Clausewitz or Sun Zi. Both stress the independence of mind that goes into inventing good stratagems and making wise choices. The point of using mathematical language here is to drive home the basic difference between the two thinkers that I have attempted to state above in ordinary English. Clausewitz is an “integral strategist,” concerned with prolongation of effort, the summing up of various components of a strategy at a culminating point—the entire area under the curve. Sun Zi is what might be called a “differential strategist,” concerned with timing, turning points, and the ever-changing play of circumstances and opportunities. His ideal war is one in which the fighting diminishes to zero: in other words, in which the short and decisive battle reaches its limit, as an infinitesimal.

The phenomenon they examine is the same. But their approaches are both mutually exclusive and mutually necessary for completeness, just as differentiation and integration are in mathematics.

Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

January 2007

Notes

is usually put into English as “the art of war,” which suggests a closeness of theme to Clausewtiz’s Vom Kriege, which unquestionably means “on war.” But bing in Chinese usually means soldier, and Sun Zi, as Mair makes clear in his notes and as is evident from the text, is almost entirely concerned with military methods that can lead to victory, rather than with war as a general phenomenon. In his first chapter Sun Zi says a certain amount about the importance of war to the state and the perils of waging it unsuccessfully. But he is not concerned, as Clausewitz is, to isolate the philosophical essence of war, in the manner that German philosophers among his contemporaries did, in their studies of history, aesthetics, morals, or similar topics.

is usually put into English as “the art of war,” which suggests a closeness of theme to Clausewtiz’s Vom Kriege, which unquestionably means “on war.” But bing in Chinese usually means soldier, and Sun Zi, as Mair makes clear in his notes and as is evident from the text, is almost entirely concerned with military methods that can lead to victory, rather than with war as a general phenomenon. In his first chapter Sun Zi says a certain amount about the importance of war to the state and the perils of waging it unsuccessfully. But he is not concerned, as Clausewitz is, to isolate the philosophical essence of war, in the manner that German philosophers among his contemporaries did, in their studies of history, aesthetics, morals, or similar topics. meaning “force,” is used only nine times in all thirteen chapters of Sun Zi, with some of these occurrences being negative in implication, in fact, warnings against the misuse of force. The corresponding German word, Gewalt, by contrast occurs eight times in just the two paragraphs in which Clausewitz defines war.

meaning “force,” is used only nine times in all thirteen chapters of Sun Zi, with some of these occurrences being negative in implication, in fact, warnings against the misuse of force. The corresponding German word, Gewalt, by contrast occurs eight times in just the two paragraphs in which Clausewitz defines war. in which the state is being stably ruled, and render it luan

in which the state is being stably ruled, and render it luan  which is to say, chaotic. The Chinese populations for control of which the kings of the warring states contended had no nationalistic passions of the sort that enflamed the Napoleonic Wars. Provided rule was not too onerous, they cared no more about which kingly clan was in charge than did German farmers in the Holy Roman Empire about which of a changeable constellation of nobles and ecclesiastical authorities had sovereignty over them. With Sun Zi we are in a world that corresponds to the European world of dynasties, in which kings fought with specialized armies and ordinary people cared little about the outcome of war. Clausewitz writes about quite a different world, most importantly, one in which national identities are congealing and national passions have been released.

which is to say, chaotic. The Chinese populations for control of which the kings of the warring states contended had no nationalistic passions of the sort that enflamed the Napoleonic Wars. Provided rule was not too onerous, they cared no more about which kingly clan was in charge than did German farmers in the Holy Roman Empire about which of a changeable constellation of nobles and ecclesiastical authorities had sovereignty over them. With Sun Zi we are in a world that corresponds to the European world of dynasties, in which kings fought with specialized armies and ordinary people cared little about the outcome of war. Clausewitz writes about quite a different world, most importantly, one in which national identities are congealing and national passions have been released. which we may call “assessment” (the word’s origin is “to weigh”); shi,

which we may call “assessment” (the word’s origin is “to weigh”); shi,  which should be understood as all of the factors and tendencies bearing on a possible battle, and which Mair translates marvelously as “configuration”; then ji,

which should be understood as all of the factors and tendencies bearing on a possible battle, and which Mair translates marvelously as “configuration”; then ji,  which indicates the moment at which the “configuration” of the various influences is most propitious for action; and finally mou,

which indicates the moment at which the “configuration” of the various influences is most propitious for action; and finally mou,  which is often translated by the little-used English word “stratagem,” a term that suggests not simply an “operational plan” as it would be called today, but in particular an operational plan that extracts maximum value from psychological as opposed to material factors. An ambush is a stratagem; a frontal attack is simply an operational plan.

which is often translated by the little-used English word “stratagem,” a term that suggests not simply an “operational plan” as it would be called today, but in particular an operational plan that extracts maximum value from psychological as opposed to material factors. An ambush is a stratagem; a frontal attack is simply an operational plan. When Westerners think of deception their minds will likely turn to dummy tanks and guns or, at the best, to the successful allied effort to mislead the Germans as to where the D-Day landing would occur. No Western strategist, and certainly not Clausewitz, would ever put deception at the heart of military method. Yet Sun Zi does this. The fact is clear linguistically. In Chinese philosophy, the moral way, or dao,

When Westerners think of deception their minds will likely turn to dummy tanks and guns or, at the best, to the successful allied effort to mislead the Germans as to where the D-Day landing would occur. No Western strategist, and certainly not Clausewitz, would ever put deception at the heart of military method. Yet Sun Zi does this. The fact is clear linguistically. In Chinese philosophy, the moral way, or dao,  is what gives rulers their legitimacy and society its cohesion. Sun Zi makes this clear at the very beginning of his treatise. The centrality of the concept in general political thought means that its manipulation must also be central. To twist the dao itself and create a deceptive dao is to subvert the foundation upon which all society and human activity is believed, by Chinese philosophers, to rest. Doing so is therefore far more grave and potentially far more powerful than any mere “deception” would be in the West.

is what gives rulers their legitimacy and society its cohesion. Sun Zi makes this clear at the very beginning of his treatise. The centrality of the concept in general political thought means that its manipulation must also be central. To twist the dao itself and create a deceptive dao is to subvert the foundation upon which all society and human activity is believed, by Chinese philosophers, to rest. Doing so is therefore far more grave and potentially far more powerful than any mere “deception” would be in the West. ],” meaning “to throw into confusion and panic” and is used especially with Yahweh as subject and an enemy as object within a holy war context. The associated noun mehumah [

],” meaning “to throw into confusion and panic” and is used especially with Yahweh as subject and an enemy as object within a holy war context. The associated noun mehumah [ ] denotes “the divine consternation or panic” produced by Yahweh’s self-manifestation, through storms.

] denotes “the divine consternation or panic” produced by Yahweh’s self-manifestation, through storms. the Chinese “Heaven,” lacked the anthropomorphic features of the Yahweh or Ba‘al or Pallas Athena, but it could intervene in battle, through the power of virtue, or de

the Chinese “Heaven,” lacked the anthropomorphic features of the Yahweh or Ba‘al or Pallas Athena, but it could intervene in battle, through the power of virtue, or de

) would never need to use force. His moral example would be enough to give order to his realm. The proof text is the classical account of how the Zhou dynasty overthrew the corrupt Shang at the semilegendary battle of the Wilderness of Mu [Muye]

) would never need to use force. His moral example would be enough to give order to his realm. The proof text is the classical account of how the Zhou dynasty overthrew the corrupt Shang at the semilegendary battle of the Wilderness of Mu [Muye]  in 1045 B.C., which Confucian philosophers took as the prototype of proper warfare. According to the Classic of Documents, the Shang troops “would offer no opposition to our army. Those in front inverted their spears and attacked those behind them, till they fled, and the blood flowed.” The victory was achieved by the working of Zhou virtue on the Shang forces. The empire was restored in the same way: King Wu of Zhou “had only to let his robes fall down, and fold his hands, and the empire was orderly ruled.”

in 1045 B.C., which Confucian philosophers took as the prototype of proper warfare. According to the Classic of Documents, the Shang troops “would offer no opposition to our army. Those in front inverted their spears and attacked those behind them, till they fled, and the blood flowed.” The victory was achieved by the working of Zhou virtue on the Shang forces. The empire was restored in the same way: King Wu of Zhou “had only to let his robes fall down, and fold his hands, and the empire was orderly ruled.”