LIFE HAS RETURNED TO almost normal.

The hole in the foyer has been fixed. The carpets have been professionally cleaned. Phil’s house has been painted a whole new color, a very attractive royal blue. Best of all, Dad and Caroline seem back on an even keel again; I don’t hear them arguing anymore about what happened on New Year’s, or about dishes or socks. And Schrödinger is completely recovered; in fact, Ashley says I’d better put him on a diet because he’s getting fat.

Also, we’ve hung Mom’s painting of the bowl of fruit over the fireplace in the living room. Everyone likes it. Even Ashley. And it makes me happy that we can all see one more reminder of the amazing person my mom was.

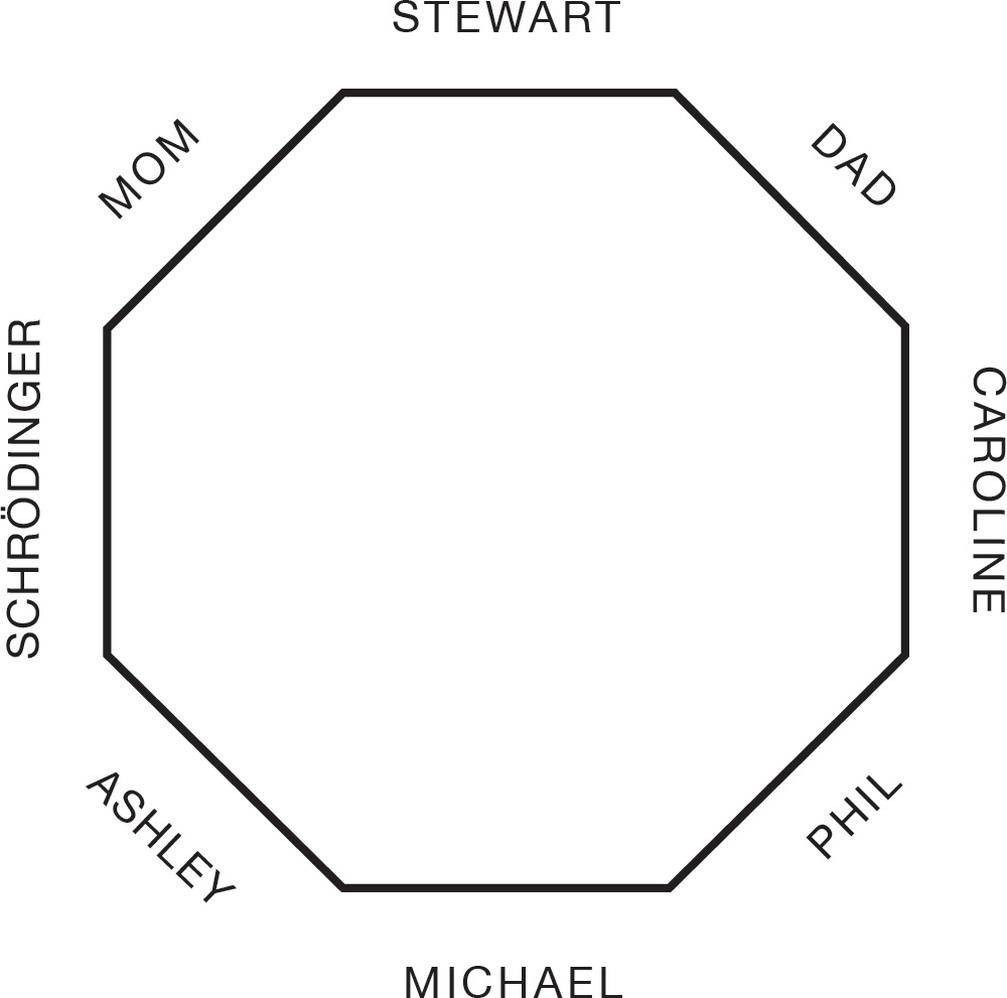

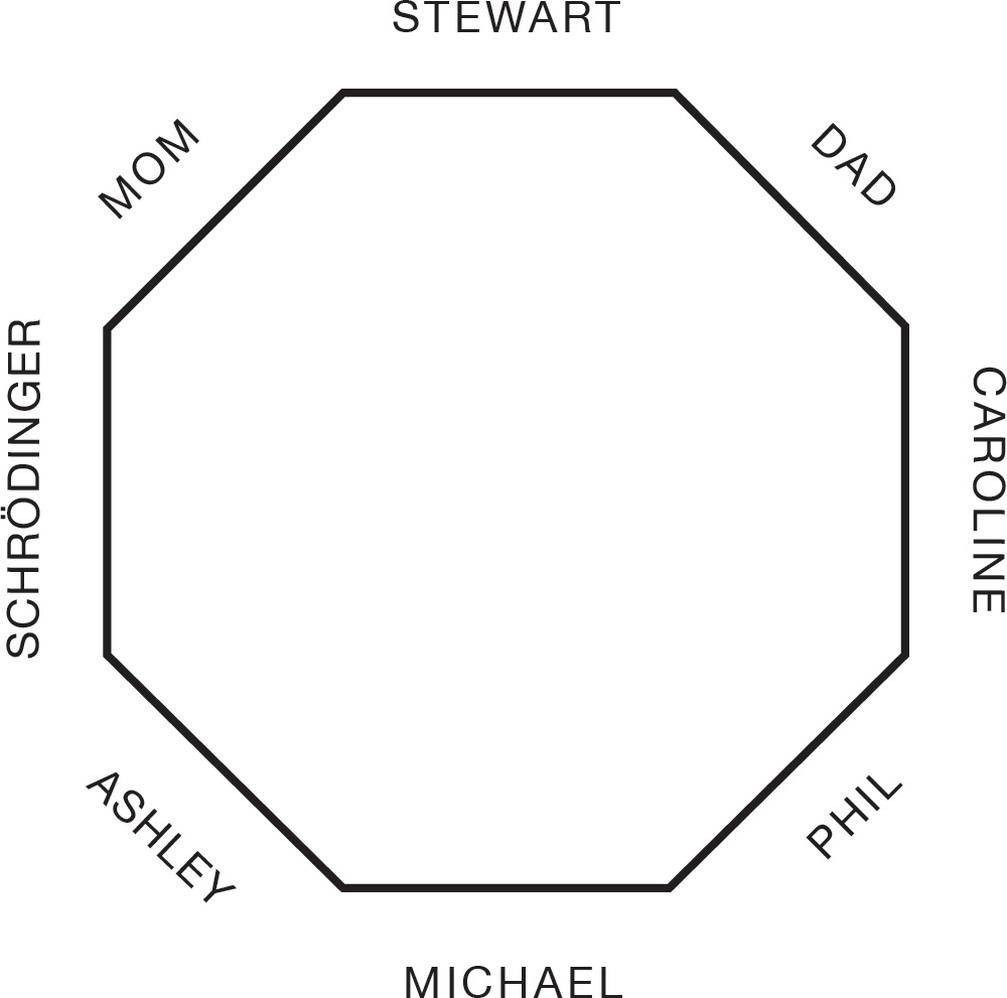

Now I think of my new family not as a quadrangle, but as an octagon.

I have concluded that Mom belongs there along with everyone else, because her memory—and her molecules—live on.

—

I’VE BEEN BACK AT Borden for a month. Dad walked with me on my first day after the suspension ended. We went to Mr. Stellar’s office and handed in my mascot outfit. Mr. Stellar told me I was the most enthusiastic mascot the team had ever had, and he was sorry to lose me. But after what had happened, he had no choice.

Then we went to the counselor’s office. A lot of kids stared at me as we walked down the corridor. A surprising number of them high-fived me.

Sylvia managed to get me into a different phys ed class for the rest of the year so I wouldn’t have to face Jared in the change room. It was a start. Then Dad dropped me at my first class. “Call me anytime if you need me.” He was worried. I couldn’t blame him; I was worried, too.

A couple of kids in my class were wearing matching blue scoop-neck T-shirts and purple berets, but I didn’t think much of it. When the bell rang, I walked into the hallway. The blue shirts followed me. A few kids in purple shirts and blue berets—including Phoebe, Violet, and Walter from Mathletes—joined them. And then, the biggest shock of all: Ashley appeared, wearing one of the blue T-shirts and a purple beret. They flanked me and walked me to my next class. “What is this?” I asked.

“Think of us as your sort-of bodyguards,” said Ashley.

To say I was surprised would be an understatement.

“I hate this stupid hat,” muttered Walter, and he yanked it from his head.

“I second that,” said Phoebe, taking hers off, too.

“I third it!” said Violet, and she flung her beret like a Frisbee into a nearby garbage can. The others did the same.

“But it’s part of the ensemble!” Ashley protested, plucking the berets out of the trash.

“Ensemble for what?” I asked.

She explained that the Friday before I returned to school, she, Phoebe, Violet, and some others had managed to get close to twenty kids signed up for their new “protection squad” program. It wasn’t as many as they’d hoped for, but it was a start. Over the weekend, Michael helped her source the T-shirts, and they’d got them dirt cheap. Then Ashley and Jeff went on a sewing binge all weekend in Phil’s laneway house, creating the berets, which hardly anyone, it rapidly became clear, would wear.

By the end of my first week back, almost forty kids were signed up. They didn’t just protect me; they escorted any student who felt uneasy about Jared, or about anyone else.

I’ve seen Jared dozens of times now. He doesn’t seem nearly as scary, or cocky. Is this because of the protection squads? Maybe a little. He knows a lot of people—not just the squads, but the principal and the teachers, too—are keeping an eye on him. And it hasn’t hurt that a tenth-grade rugby player named Darren has taken quite an interest in Ashley. He seems like a real step up from Jared: he’s a genuinely nice guy who also happens to be built like a Mack truck. He was intrigued when he saw all these people walking around in purple and blue. Ashley told him what it was about, and he signed up. He also got a bunch of his teammates to sign up, so by the end of the second week, the protection squad’s numbers soared to over fifty. I heard through the grapevine that Darren also took Jared aside one day and told him that if he so much as touches me or anyone else, the entire rugby team will be after him. So, while I would never say this to Ashley, Darren’s threat might have had a bigger effect on Jared than a bunch of kids in purple and blue.

Still, I can’t believe Ashley managed to put some of the power back into the hands of the little people. That Ashley wound up being a force for change. I told her another one of my favorite Einstein quotes: “The world is a dangerous place to live, not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.”

She just looked at me and said, “How that man went out in public with that hair is beyond me.”

But she’s proud of what she’s done. Being Ashley, when I call the T-shirts blue and purple, she corrects me. “Indigo and aubergine.”

I can tell she still misses Lauren. But I’m pretty sure that friendship is over. One day Lauren was in tears at her locker, and I saw Ashley try to talk to her, but Lauren just told her to eff off.

Except she didn’t say “eff.”

—

EVERY NOW AND THEN, Ashley and I have moments where we genuinely connect. Like recently, I helped her come up with a structure for the new essay she had to write on To Kill a Mockingbird. After she’d finally finished reading the book, I rented the movie for us one night. Her comment? “Gregory Peck is super-handsome!” Then she turned her gaze from the screen to me. “Hmm. Interesting,” she said. “Gregory has sticky-outy ears, too. Just like you.”

“So?” I asked.

“So there’s hope for you yet.”

And at the end of my first week back to school, she actually asked for my input on finding a good name for the squads, because she wanted to get it printed on the T-shirts. We both agreed Protection Squad sounded too negative, and so was Anti-anything.

So I suggested a name and, miracle of miracles, Ashley liked it.

That’s what’s printed on all the T-shirts now.

WE ARE ALL MADE OF MOLECULES.