Chapter Six

Legitimacy and Global Governance

Introduction

This chapter will explore the idea of legitimacy in relation to global governance institutions by critically assessing three of the major accounts available in the field: the state consent, democratic and meta-coordination accounts.1 The argument will be that the state consent account generates a number of major difficulties and cannot be readily adapted to the complex and changing circumstances of global politics. While the democratic approach to legitimacy fares considerably better, it leaves open a number of major questions, which need further examination. The third approach, the meta-coordination view set out by Allen Buchanan, makes a number of important advances and offers much needed flexibility and adaptability in relation to the diversity of global governance institutions. However, Buchanan's view needs to be further developed in order to provide robust guidance on how to assess different types of global governance institutions.

Two concepts are central to our discussion: legitimacy and global governance. We understand legitimacy to refer, broadly speaking, to the difference between the imposition of rules or norms and their acceptance because of sound normative reasons. Legitimacy entails that rules and institutional arrangements are in some sense worthy or just, and thus should be followed for reasons other than expediency or the threat of sanctions. Furthermore, legitimacy confers a certain standing on institutions. There are different ways of portraying the precise nature of this standing, but we think that it is best to conceive it as a kind of respect for institutional directives. The latter idea can be contrasted to the much narrower use of the term that is often employed in technical discussions within political philosophy. In more technical language, political legitimacy is often understood as the claim of an agent to have a right to rule over some other agent with respect to a given domain. A right to rule correlates to a duty to obey. A duty to obey can be understood in different ways, but it usually entails that those who have such a duty consider the directives issued by the legitimate authority as providing them with content-independent reasons to follow them (see Lefkowitz in this volume for a more detailed treatment). When we use the term legitimacy in this chapter, we refer to the broader definition of the term. Employing what we have called the technical definition would, for our purposes here, unduly narrow the discussion (see section 2 for a fuller discussion).

By global governance, we refer to a complex mixture of multilateral and transnational governance arrangements. Global governance is multilayered insofar as the making and implementation of global policies can involve a process of political cooperation and coordination between suprastate, national, transnational and often substate agencies. It is a highly differentiated sphere: the politics of global trade regulation is, for instance, distinct from the politics of climate or peacekeeping. Rather than being monolithic or unitary, the global governance system is best conceived as sectoral or segmented. Moreover, many of the agencies of, and participants in, the global governance complex are no longer simply public bodies; it is a multiactor complex in which diverse agencies participate in the formulation and conduct of global public policy. The complexity and polycentricity of global governance is an important backdrop to the discussion below.

1 The State Consent Theory of Legitimacy

According to the consent-based approach to legitimacy, an institution is legitimate only if its subjects-to-be have consented to it. This view, originally associated with the work of Hobbes, Grotius, Locke and Pufendorf (see Hampsher-Monk, 1993), has been more recently revived by Simmons (2001). The basic idea is that what binds us to an institution is the voluntary acceptance of its authority. From an historical perspective, the idea that consent grounds legitimacy constitutes a strong departure from traditional Christian perspectives as developed in Western Europe. In this Christian worldview, human beings are part of an immutable order of nature. Their subjection to political authority is coextensive with their subjection to God. The consent approach to legitimacy provides a dramatic transformation of the way we conceptualize the political sphere. If we accept the consent view, it is the individual who determines his or her political obligations. The focus in this section is, of course, the state consent theory of the legitimacy of global governance institutions. This theory essentially transposes the traditional consent-based view and applies it to the realm of international politics. According to this account, a global governance institution is legitimate if it has been created via the consent of the states that will be subject to it (see Held, 2002).

A consent-based account of global governance institutions fits closely with the traditional conception of Westphalian sovereignty. Reflecting on the intense religious and civil struggles of the sixteenth century, Bodin (1992) argued for the establishment of an unrestricted ruling power competent to overrule all religious and customary authorities. In his view, an ‘ordered commonwealth’ depended on the creation of a central authority that was all-powerful. While Bodin was not the first to make this case, he developed what is commonly regarded as the first statement of the modern theory of sovereignty: that there must be within every political community or state a determinate sovereign authority whose powers are decisive and whose powers are recognized as the rightful or legitimate basis of authority. Sovereignty, according to him, is the undivided and untrammelled power to make and enforce the law and, as such, it is the defining characteristic of the state.

The doctrine of sovereignty developed in two distinct dimensions: the first concerned with the ‘internal’, and the second with the ‘external’ aspects of sovereignty (see Hinsley, 1986; Cassese, 1995). The former involves the claim that a person, or political body, established as sovereign rightly exercises the ‘supreme command’ over a particular society. Government – whether monarchical, aristocratic or democratic – must enjoy the ‘final and absolute authority’ within a given territory. The latter involves the assertion that there is no final and absolute authority above and beyond the sovereign state. In the traditional conception of external sovereignty, nothing but the will of the sovereign can effectively bind the state. It follows that international institutions can only be legitimate if they can rely on the consent of the subjects over which they claim authority, namely, sovereign states.

This ‘classic’ conception of sovereignty envisages the development of a world community consisting of sovereign states in which states are, in principle, free and equal; enjoy supreme authority over all subjects and objects within a given territory; form discrete political orders with their own interests; engage in diplomatic initiatives and ensure cooperation between states, if and only if this cooperation is in their mutual interest and reduces transaction costs. Territorial sovereignty, the formal equality of states, non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other recognized states and state consent become the basis of international legal obligation and the core elements of international law (see Crawford and Marks, 1998). Of course, this conception of sovereignty was often ignored by leading powers seeking to carve out particular spheres of influence. The reality of classic sovereignty was often messy, fraught and compromised (see Krasner, 1999). But this should not lead one to ignore the systematic shift that took place in the principles underlying political order with the rise of the modern sovereign state.

Yet, right from the beginning, the state consent theory of legitimacy exhibited a number of problems. The first and most obvious is that to conceive of consent as both necessary and sufficient for legitimacy may be deeply counterintuitive if what is consented to is grossly immoral (Estlund, 2009). One could call this the ‘immoral consent’ problem. An example of this is that most people would feel uncomfortable with the idea that an institution is legitimate if its members have consented to it while, at one and the same time, the institution operates in a way that violates basic human rights. As the old adage goes, the fact that something is accepted need not be a good guide to what is acceptable. This is not, of course, to claim that consent is irrelevant to the legitimacy of an institution. In a democratic age, the latter claim would be highly implausible. However, it tells us that a completely procedural view of the legitimacy of an institution based on consent intuitively runs counter to our considered convictions about both sufficient and necessary conditions for legitimacy.

Second, according to most accounts of the consent theory of legitimacy, the normative force of consent can only be obtained if consent has been genuinely given. This is contrary to the Hobbesian view that norms and institutions can be legitimate even if they are accepted through coercion, manipulation, substantially asymmetric bargaining circumstances or lack of epistemic awareness. Valid consent is always free and informed consent. The idea of free and informed consent needs to be qualified in some respect. In the first instance, it is reductive to imagine that the only properties that can be attached to ‘consent’ are binary distinctions such as ‘free/unfree’ and ‘informed/uninformed’. For example, Held (2006: 155) develops a typology based on seven different ways in which consent can be given. To mention just two options, consent can be given as a result of unreflective choices based on tradition, or because we lack specific preferences in relation to what we consent to. Furthermore, even accepting the relevance of the aforementioned binary distinctions, the latter rely on epistemically and normatively loaded concepts. How much information is enough to justify the label ‘informed’? And what counts as a freely undertaken choice? For example: up to what point are market transactions freely undertaken given the background of unemployment and financial constraints that some market actors face? Similarly, voters regularly express their political preference and cast their ballots without necessarily being fully aware of the nature of the political options available to them; nor, often, do they have a satisfactory epistemic understanding of the technical issues linked to various economic and social policies proposed by different parties and coalitions. Is the average voter's ballot an expression of informed consent? Can we say it meets the standards of deliberative reasoning (Fishkin, 1991; Offe and Preuss, 1991)? Needless to say, these are questions that we will not be able to settle here.

Thus, while stating that valid consent must be free and informed seems a sound way of putting restrictions on what constitutes valid consent, the claim is not necessarily very helpful. As such, these restrictions do not easily help us to specify concretely which instances of consent are genuinely free and genuinely informed. They do provide a benchmark, but only a very abstract one. The presence of largely grey areas, and difficult cases, should not, however, preclude the assessment of more clear-cut scenarios. Some instances of consent are easy enough to classify: consenting to the highway robber who ‘asks’ for our money in return for our lives is not what most of us would consider as free consent. In the same way, young children cannot enter into contractual relations because we believe that their age precludes them from fully understanding what they would be agreeing to.

One way to take the argument forward is to note that what seems to be central in all the aforementioned cases are the background circumstances under which consent is given, such as the extent to which those who have consented knew what they were consenting to, or the implications, from a moral point of view, of not consenting. Given that background circumstances are important to determine the nature of consent, how does the state consent approach to the legitimacy of global governance institution fare? A significant number of international interactions and agreements, in the first instance, clearly run afoul of the ideas of free and informed consent. Having a seat at a negotiating table in a major international organization or at a major conference does not ensure effective representation; even if there is a parity of formal representation, it is often the case, for example, that developed countries have large delegations equipped with extensive negotiation and technical expertise, while poorer developing countries often depend on one-person delegations, or even have to rely on the sharing of a delegate (see Held, 2004: 95–6). The latter example enables us to portray what we can call the ‘uninformed consent’ problem that plagues global governance institutions. A substantial number of their members are simply unable to process all the relevant information that would allow them to be fully informed about the agreements they are subscribing to. In the same way, given the bargaining asymmetries that characterize international negotiations, the state consent theory is unlikely to provide a satisfactory general account of the legitimacy of global governance institutions. If consent must be ‘free’ in order to be valid, the large imbalances in economic and political power between negotiating parties clearly cast a shadow on its validity. Put differently, global governance institutions suffer from a ‘coerced consent’ problem.

These concerns are also reinforced by the development of the international system from the 1960s onward. As Robert Jackson (1990) has argued, decolonization has allowed a large number of former colonial countries to become independent. However, their formal independence, what Jackson labels as negative sovereignty, was often not matched by their substantive ability to govern themselves and to become institutionally and politically self-standing, or what should otherwise be understood as positive sovereignty. In other words, the international system after the decolonization process can be described as an arena where a large number of players are essentially unable to stand on their own, and are instead ‘territorial jurisdictions supported from above by international law and material aid’ (Jackson, 1990: 5). In a world of ‘quasi-states’, the state consent theory seems a peculiarly unsound guide to the legitimacy of global governance institutions. Quasi-states lack both the bargaining power and, often, the technical capabilities to consent genuinely to the way in which global governance institutions are run.

There are two further limitations found in the state consent view of the legitimacy of global governance institutions. The first is that global governance is increasingly difficult to capture simply through the lens of state-to-state interactions (Weiss and Wilkinson, 2014). Call this the ‘scope’ problem. The massive growth of transborder governance arrangements has transformed the very way in which we conceptualize global politics. The global political domain is still the stage for power politics between states. However, it certainly cannot be fully captured simply through a state-to-state lens. The latter idea is based on the appreciation of what we take to be two central structural changes in the global political domain since the Second World War (see Held, 2014). First, global governance has been characterized by the proliferation of influential nonstate actors. From multinational corporations (MNCs) to international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), the global political landscape has evolved and become more complex, with a vast array of agents actively participating in the formation of global policy. Second, and relatedly, global governance arrangements have been increasingly characterized by new types of institutional arrangements. In many issue areas, and to different extents according to the issue area, global governance institutions are not simply constituted by state-to-state interactions. The case of global finance stands out in this regard (e.g. the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the Financial Stability Board), but other examples include global health governance (e.g. the Global Fund, the GAVI alliance, and polio eradication efforts) and climate governance (which seeks to coordinate diverse actors in relation to a single norm – 2 per cent as the agreed limit placed on climate change) (Held, 2014: 65).

In short, the contemporary global governance system has features of both complexity and polycentricity, as noted above in the Introduction. Such features are, simply put, impossible to assess if we remain anchored to a view of the global political domain that is based solely on the actions and interactions among political communities. In this respect, then, the state consent view is incomplete and unable to function as a tool for the critical scrutiny of the legitimacy of existing global governance institutions. Or to put the point differently, even if one accepted the normative correctness of the state consent theory, the latter would be irrelevant when it comes to legitimacy assessments concerning many global governance institutions.

Of course, those who subscribe to the state consent view may reply that our objection cannot really demonstrate that the state consent approach is inadequate. It is, they could say after all, a normative view about how global governance should be, and not a descriptive account. At best, the scope problem can show that some global governance institutions are illegitimate given that they are not subject to state consent. Such a position would have implications for large parts of contemporary global governance arrangements, indicating that they cannot have an authoritative role in the spheres in which they operate. If this judgment were taken seriously, however, it could have profound negative implications for the efficacy of global governance.

Those who favour the state consent view might reply that we do not need to consider an institution legitimate in order to believe that following its directives is, ‘all things considered’, required. Put differently, even illegitimate institutions may generate directives that we have independent reasons to comply with. While, theoretically, this is certainly an option, it is not one we find appealing. First, note that, in this context, nothing much seems to follow from the fact that an institution is illegitimate. Second, it is unclear how exactly one can generate effective forms of institutional cooperation if one denies the legitimacy of a substantial part of global governance and leaves the decision to comply with global governance institutions to a case-by-case approach.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the state consent theory of legitimacy becomes increasingly less tenable to the extent that withholding consent may have severe externalities. Call this the ‘externalities’ problem. This seems to be the case for global governance institutions that serve, in principle, the purpose of solving collective action problems, or addressing ‘global public bads’ such as climate change, pandemics, financial instability and nuclear proliferation. These global public bads are indicative of three core sets of challenges we face – those concerned with (a) sharing our planet (climate change, but also biodiversity losses and water deficits); (b) sustaining our humanity (global pandemics, but also conflict management and prevention); and (c) developing our rulebook (nuclear proliferation treaties, but also global international trade and taxation regimes) (see Rischard, 2002). In our increasingly interconnected world, these global problems cannot be solved by any one nation-state acting alone. They call for collective and collaborative action (Held, 2004: 11–12). The state consent view of legitimacy essentially gives unlimited opting-out powers to states and, yet, given the global collective action problems we currently face, withholding consent from even reasonable attempts at their solution may imply imposing severe costs on others. Put differently, consent must be limited by the type of externalities it generates. Of course, it is open to those who favour the state consent view to claim that the latter contention is not very informative without a clear account of the externalities in question and, in the present context, without a clear picture of what kind of externalities we may permissibly impose on others. We cannot fully address this point here. However, we think that at least for a central class of cases that are at the heart of global governance, such as climate change, prudential financial regulations and nuclear proliferation, the types of externalities involved would, in the absence of cooperation, have important implications for the basic interests of humankind. Accordingly, they would be part of any plausible account of the kind of externalities we are not allowed to impose on others.

In this section, we have argued that the state consent theory of legitimacy is not a credible position. We have highlighted what we take to be five important problems with the state consent view, namely immoral consent, uninformed consent, coerced consent, scope and externalities. The first three problems are relatively familiar in traditional discussions of the consent view of legitimacy. They arise because consent is a procedural notion that provides no indication about the content of what is consented to and because the background conditions under which agents consent to something often invalidate the normative relevance of what is agreed to. The remaining two problems pertain to the extent to which the state consent position, as an application of the more general position that consent legitimizes institutions, is a plausible guide to the legitimacy of global governance institutions. They emerge because we live in a world where globalization has altered the types of agents that actively participate in the formation of global governance norms and regimes, and in which withholding consent can effectively represent, at least in the long run, an existential threat to the whole planet. These two objections to the state consent view of the legitimacy of global governance institutions tell us that even if we were to accept the moral justification linked to consent-based approaches to legitimacy, the current conditions of global politics make it an implausible candidate to judge global governance institutions.

Given the problems highlighted, it is natural to look elsewhere for a satisfactory account of the legitimacy of global governance institutions. The most important alternative suggested in the literature on the legitimacy of international and transnational institutions is democracy. Democracy often appears to legitimate modern political life: rulemaking and law enforcement often seem justified and appropriate when they are ‘democratic’. Of course, it has not always been so. A general commitment to democracy is a very modern phenomenon and the extension of the idea of democracy to the global domain is an even more recent phenomenon, marking a shift from a world of national communities of fate to a world of overlapping communities of fate – where the fortunes of countries are densely interwoven (Held, 2006). However, the idea of extending democracy beyond national communities has recently been subjected to a number of criticisms. Many have argued that democracy is inadequate to provide us with a relevant normative benchmark to assess global governance institutions. In the next section, we address what we believe to be some of the most sophisticated versions of these arguments. Our provisional conclusion is that, while such critiques are insightful, they do not provide conclusive reasons to abandon the democratic account in all respects.

2 The Democratic Account

Given the success of democratic forms of governance at the domestic level, it is hardly surprising that democracy has been proposed as a form of benchmark for the assessment of the legitimacy of global governance institutions. There are different ways of conceiving both how democratic decision-making confers legitimacy on institutions in general and how democracy can be understood as a relevant standard for global governance institutions.

Some accounts of democratic legitimacy rest exclusively on the empirical claim that democratic forms of governance are uniquely placed to produce good outcomes or decisions, while other accounts claim that the legitimacy of democratic institutions is the result of the democratic character of the decision-making procedure (for a discussion of the distinction and its relevance to legitimacy, see Peter, 2010; see also Christiano, 2008). Others still (see Peter, 2008; Christiano, 2012b) argue that the two dimensions (i.e., substantive and procedural) are irreducible to one another and, thus, that a successful account of the legitimacy conferring properties of democratic governance will rest on some form of combination between the two.

The idea of a democratic conception of the legitimacy of global governance is also closely connected to the idea of global democracy. Needless to say, there is more than one account of global democracy, and hence it is useful to say something more specific about what we mean by a democratic account of the legitimacy of global governance institutions. One characteristic way of classifying different models of global democracy is to analyse the different conceptions of the demoi upon which such models are built (Archibugi et al., 2011; Held, 1995, 2006; see also Marchetti, 2008). The first model of global democracy is based on intergovernmentalism and views global democracy as an international form of association based on the membership of democratic states. The second, transnational model, is based on the idea of stakeholdership and constitutes global democratic demoi through the application of the all-affected principle. The third model is the most inclusive and considers all human beings as members of a global demos qua individuals, rather than as national citizens or affected parties. In the latter model, a necessary condition for global governance institutions to be legitimate is that every human being should have an equal say in how these institutions operate and function. Accordingly, each model of global democracy offers a different account of the democratic bases of the legitimacy of global governance institutions.

In what follows we will not take a stand on which account of democratic legitimacy is the correct one. Our discussion below will be largely compatible with a number of ways of understanding what grounds democratic legitimacy. Rather, we will assume a specific account of global democracy, namely, the global demos model. This is for two reasons. First, we consider the latter to be the most inclusive and coherent one in order to assess the plausibility of democracy as a standard for global governance; and, second, most of the arguments we address below use, implicitly or explicitly, the global demos model as a critical target.

Several criticisms have been levelled against the democratic account of the legitimacy of global governance institutions. In what follows we assess two of them. The first considers the democratic principle as grounded on specific assumptions about background political conditions, some of which, so the argument goes, are absent in global politics. In other words, democratic rule presupposes a very specific set of empirical circumstances in order to be morally justified. In turn, the absence of at least a number of these empirical presuppositions invalidates the use of democracy as a benchmark for legitimacy assessments. Thomas Christiano (2010) has developed a powerful version of this argument. The second objection, initially developed by Allen Buchanan and Robert Keohane (2006), contends that the democratic model of legitimacy is constructed on the features of the traditional territorial state and thus is simply not applicable to institutions (i.e., global governance institutions) which are different in several normatively salient respects. We are broadly sympathetic to the overall concerns raised by Christiano. However, we contend that the way in which global politics is currently articulated makes the applicability of Christiano's arguments to global governance institutions precarious. In a similar way, we tentatively agree with Buchanan and Keohane that the complexity of global governance institutions may put pressure on the appropriateness of the applicability of the democratic standard. Having said this, we want to suggest that the democratic approach is more ‘flexible’ than they contend and thus that it may still have a role to play.

Christiano has put forward a sophisticated critique of the global demos account of the legitimacy of global governance institutions (2010, 2011, 2012a). More specifically, his argument highlights several conditions that need to be met if democracy can be considered an appropriate mode of governance at the global level. According to him, democracy is founded on the principle of public equality and can only realize public equality if very specific background conditions are in place. Adopting democratic forms of governance can only be justifiable when:

1. A number of important issues…arise for the whole community. 2. There [is] a rough equality of stakes among persons in the community concerning the whole package of issues. 3.…the community is [not] divided into discrete and insular groups with distinct preferences over all the issues in the community so that one or more substantial groups always lose out in majority voting.…4.…when it protects at least the fundamental human rights of all the persons in the community. 5.…when the issues with which it deals are not primarily of a purely scientific or technical character. 6.…[when] there [is] a dense network of institutions of civil society that connect[s] individuals to the activities of the democratic legislative power.

(2010: 130)

In Christiano's view, conditions 2 and 3 on the list are closely related to the assessment of democracy as a standard of legitimacy for global governance. Condition 2 allows us to understand the specificity of the global political domain. It enables us to see that domestic and global politics may be different in a normatively salient way. Condition 3 highlights a general risk that democratic rule can face, but one that is likely to be higher if the idea of democracy is extended to the international system. Appreciating the relevance of both aforementioned conditions, in turn, renders the democratic account of legitimacy inappropriate for global governance institutions.

Let us call conditions 2 and 3 put forward by Christiano the equality of stake objection and the persistent minorities objection, respectively. The equality of stake objection seeks to provide a rebuttal to one of the most commonly used arguments in favour of some version of democratic global governance, namely, that an increasing number of social, political and economic problems have made persons around the globe more closely interdependent than they once were. Such interdependence is then taken to justify some form of global democratic system insofar as some mechanism of political and institutional accountability is required to regulate political decisions that have significant spillover effects across many jurisdictions. However, Christiano argues that the latter idea is not enough to justify the recourse to democratic forms of accountability. Democracy is justified not simply by interdependence, but by interdependence characterized by a rough equality of stakes between those who participate in the democratic process. By ‘stake’, Christiano refers to ‘the susceptibility of a person's interests or well-being to be advanced or set back by realistically possible ways of organizing the interdependent group’ (2010: 131). Given this definition, the requirement of equal stakes can be interpreted as a fairness-based one: it is simply unfair to give, as democracy does, equal influence over decision-making to people who are affected in radically unequal ways by the outcomes of such decision-making. Or, in Christiano's words: ‘If one group of persons has a very large stake in a community, in which there is interdependence of interests, and another has a fairly small stake, it seems unfair to give each an equal say in decision-making over this community’ (2010: 131). However, this is precisely what would happen, he argues, if we simply applied the democratic principle beyond the nation-state. While the modern nation-state has immense institutional capacity and thus impacts individuals’ interests and welfare to such a degree that the equal stakes condition applies (i.e., the stakes are comparable because they are very high for all citizens), the same cannot be said for international laws and institutions, since the latter ‘play a fairly small role in the lives of people throughout the world’ (2010: 132).

The problem highlighted by Christiano is clearly one that goes at the heart of democratic theory, and he should be credited with raising it in the context of global governance institutions. Nonetheless, we are not convinced that the unequal stakes argument is as damaging to the supporters of global democracy as Christiano seems to suggest. First, there is, clearly, an empirical dimension to the argument. At least at first sight, the presence/absence of equality of stakes seems to rest on the empirical appraisal of concrete political circumstances. While there is no doubt that, prima facie, the vast majority of domestic political communities feature a reasonable equality of overall stakes internally and, less so, when such stakes are compared to the global level, the latter judgment needs to be qualified by the appreciation of some of the most pressing global problems we currently face. Humanity is increasingly confronted by political challenges that are momentous if not existential in nature. From climate change and environmental degradation to nuclear proliferation, pandemics, financial instability, terrorism and failed states, global problems are becoming politically disruptive for the whole of humankind. Apocalypse may be an abused term, and yet it is not necessarily out of place to describe what some of the threats we are facing could lead to if they are not properly managed. In this context, equality of stakes is not as remote as one might initially conjecture. It is perhaps less visible and immediate than in everyday domestic politics, and yet all stakes seem to be roughly equal when each stake is close to being infinitely high.

Of course, it could be objected that many problems at the global level, such as terrorism and environmental degradation, often affect different political communities in different ways. For example, oil spills are localized, while restrictions on financial flows that are used to fight the financing of terrorist activities are becoming burdensome on countries that heavily rely on remittances. These points are certainly correct. What is less clear is the extent to which they invalidate our broader argument. Several of the collective action problems we face at the global level are not easily captured by the aforementioned examples. One way to see this is to think about the very idea of how we want to define a ‘stake’. If we define it as the actual impact that some specific political event has on a specific set of people, then inequality of stakes may very well be prevalent. If, instead, we broaden the definition of ‘stakes’ to include the risks that are generated by some political and economic activities, then they are more evenly spread. In the same way, although climate governance regimes, nuclear proliferation regimes, global capital requirements regimes, etc. will, synchronically and taken individually, affect different peoples differently, in time, and taken together, their shape and very existence will affect everyone in a similar way.

These remarks also signal, in our view, the potential to reconcile our arguments with Christiano's position. Accepting that a significant set of global collective goods is congruent with the broad idea of equality of stakes may signal that, at least with respect to those important political questions, equality of stakes cannot be taken to be a decisive objection to the adoption of the global demos model. However, the latter contention is compatible with the idea that several other domains in which global governance institutions operate may not necessarily display the same type of empirical features. In those domains, it could well be correct, following Christiano, to accept that a global demos approach may be inapplicable, as it would give equal weight to unevenly affected groups. We think that the global demos model is flexible enough to accept this kind of approach.

Finally, we should note that there is a potential difficulty connected to the very structure of Christiano's argument concerning equal stakes. The fact that the modern state has immense institutional capacity, to use his words, is not a natural phenomenon. Even accepting, for the sake of argument, that inequality of stakes is prevalent, we need to ask from where, politically speaking, does this inequality originate? Equality of stakes, just like the idea of the modern state, is not a natural condition. It is, instead, the result of institutional choices: for example, the persistent uneasiness and opposition on the part of most states to the delegation of sovereign powers to other forms of organizations. However, if we accept that the modern state has a much larger institutional capacity compared to global governance institutions as a result of past institutional choices by sectional groups and powerful interests, then it becomes less clear why the equality of stakes argument matters: the point is not that equal stakes do not arise at the global level, but rather that they have not been encouraged or even allowed, institutionally speaking. The question then is: should equality of stakes at the global level be something that we should aim for? Whether or not the answer to the latter question is affirmative, it cannot be settled just by looking at the current organization of the global political landscape. To an extent, we think, Christiano could agree with the latter contention. Given his account of the normative core of democracy, he might accept that in a world where stakes were allowed to become more ‘equal’ and people had more say on a wide range of pressing issues at the global level, the equal advancement of human interests is best served. As we have highlighted above, this does indeed seem to be the case for an important class of global collective goods.

The second objection we will discuss highlighted by Christiano is connected to the idea of permanent minorities. Once again, we believe the argument presented by him deserves careful consideration as it is central to the question of the desirability of global democracy. However, while the issue merits attention, and should clearly work as a factor that cautions us against easy transpositions of the democratic mode of governance into global politics, we are also convinced that the empirical picture suggested by Christiano is only partially convincing. He describes the problem as follows:

If the issues upon which a democratic international institution makes decisions are such that discrete and insular coalitions tend to form (with some forming a majority and some forming minority blocs), then there is a significant chance that some groups will simply be left out of the decision-making process. And this leaves open the possibility that their lives will be heavily determined by strangers.

(2010: 133; emphasis added)

Christiano goes on to distinguish the problem of permanent minorities from the problem of the tyranny of the majority: while the two often go together, they need not do so conceptually speaking, as it is entirely possible that a permanent majority could treat members of a permanent minority in accordance with human rights even while denying the minority any input into the decision-making process (2010: 134). Christiano also qualifies his concern for the formation of global permanent minorities by observing that we cannot know in advance whether such a problem would in fact occur, and that even if it occurred it could, at least potentially, be addressed through the same types of institutional mechanisms that are used within domestic democratic settings. However, he concludes that the prospects for such institutional solutions to emerge are poor given the comparative weakness of global civil society (2010: 134).

As we have mentioned above, it is hard to disagree with Christiano about the importance of the problem of permanent minorities: they are certainly an issue. However, at the empirical level, the way in which new global problems are generated by globalization seems to render this critique partly inert. The fact of globalization and the rise of what some have called intermestic issues (see Rosenau, 2002) suggest that there is no way (or at least no sensible way) to retreat from certain domains of international or transnational interaction. Clearly, the latter is not an uncontroversial claim (however, see Held et al., 1999; Held and McGrew, 2007; Hale et al., 2013). Yet it is important to pause and ask ourselves what the truth of such a claim would imply for the permanent minorities argument. The fact that we may consider global democracy as morally unattractive because it might engender permanent minorities seems to rely on the existence of an alternative framework, one in which, by not engaging in democratic forms of global governance, one could avoid the formation of permanent minorities. Such an arrangement could perhaps be one in which all countries retreat to their own political backyard. But how plausible is this alternative background picture? Is it empirically and politically credible? If, for example, as we have suggested, globalization makes the retreat to domestic politics increasingly difficult, then this background picture is simply not one that we can seriously entertain. The most credible alternative scenario, alas, is the one we are facing right now: the existence of permanent political minorities without the (albeit minimal) guarantees of the democratic process. Instead of permanent minorities within shared institutional settings, what we get is peoples with no say over institutions that will affect their lives whether or not they participate in those institutions. Christiano correctly balks at the ‘possibility that (people's) lives will be heavily determined by strangers’. Yet, the world we are facing is, precisely, one in which we witness more than the mere possibility of this happening.

Christiano could argue that to deny that the current system is legitimate is not to provide an argument that supports global democracy. Put differently, the fact that we are experiencing the de facto formation of global permanent minorities on several important issues, does not disprove the contention that global democracy would suffer from the same ills. It just tells us that the dangers of permanent minorities formation are shared by the current non-democratic system and the putatively democratic one that global democrats champion. This is a fair point, though not one that is conclusive. The global democracy model could offer some guarantees that the current non-democratic system is not well placed to provide. For example, a global democracy approach could feature standards of formal representation in key global governance institutions that would allow less powerful and currently underrepresented or disenfranchised actors more leverage than they currently have and the opportunity to form coalitions. Comparatively speaking, the global democratic approach could well fare better in the precise sense of providing more political representation and voice to a larger range of actors than we currently witness.

Yet, Christiano could contend that real issue does not concern the comparative effectiveness of different arrangements with respect to the problem of permanent minorities. Rather, the problem is whether the issue is likely to arise again. Improving on what we have may not be enough if the risk of generating permanent minorities is still significant. Christiano (2011) himself has argued for what he calls the ‘fair democratic association’ (FDA) model. This is essentially an internationalist model based on the consent of democratic states. FDA, he contends, would fare better when it comes to the problem of permanent minorities, since it would allow participants to refuse to enter into treaties and institutions that they would not find acceptable or beneficial. Nonetheless, it must be stressed, as Christiano recognizes, that the price of this ability to withdraw participation is very high, given that it would engender significant problems with externalities imposed on third parties (see above). Furthermore, note that Christiano argues for the FDA model in the context of a discussion of the legitimacy of international institutions. Yet, as we have shown in section 1, global governance is subject to a proliferation of relevant actors and is thus increasingly difficult to capture in terms of state-to-state interactions. This tells us that FDA, even if justifiable as an account of the legitimacy of international institutions, cannot be easily transposed to the broader issue of the legitimacy of global governance. Finally, note that, as argued above, the global demos approach is potentially flexible and can be deployed according to its suitability for specific issue areas. Thus, it is open to global democrats to claim that the problem of permanent minorities should be one factor that cautions against the blanket application of the global democracy approach to all institutions in global governance.

To sum up, the permanent minorities and unequal stakes arguments, while normatively correct in themselves, still rest on empirically disputable accounts of global politics: equality of stakes is often a reality when humanity faces several existential threats and permanent minorities are exactly what the present system of global governance already allows, given that it embeds institutions that are only responsive to the needs of the few and affect the fate of the many.

Finally, we consider a further recent critique of the democratic account of the legitimacy of global governance institutions, namely, the one levelled by Allen Buchanan and Robert Keohane (2006). In order to understand the roots of their critique, it is important to recall a shared feature of the arguments we have put forward to assess both the state consent model and the critique of the democratic account made by Christiano. Throughout this chapter, we have stressed the importance for normative accounts of legitimacy to be isomorphic or congruent with the empirical reality that they are trying to assess. The latter view is, of course, controversial (at least when applied to debates about the nature of justice and other core moral and political concepts; see, for example, Valentini, 2009). Nonetheless, taking this point of departure seriously, we are able to put forward what we think is a prima facie sound criticism of the adequacy of democracy as a standard for the legitimacy of global governance institutions. The problem is essentially one of fit: fit between the features of global governance institutions taken generally and the features of the democratic account of legitimacy. We will not belabour the point excessively, as it has already been extensively developed elsewhere (see Buchanan and Keohane, 2006; Buchanan, 2010, 2013). The democratic account of legitimacy is a demanding one. It has been, at least initially, developed for institutions, political communities broadly understood, which possess certain important features that are morally speaking salient when it comes to the types of normative expectations we have about them. Such features are, among others, the claim to possess a right to rule and to have exclusive jurisdiction over a given domain, and the ability to attach penalties, usually physical coercion, to non-compliance. The democratic account of legitimacy is geared to reflect these features of domestic political communities: from Greek city-states to the modern nation-state, these features were and are essential elements of our understanding of the exercise of political power in territorially bound political communities (Held, 2006).

However, political power is not simply the exercise of power by institutions claiming a right to rule backed by the use of coercion and physical force. Moreover, many institutions, strictly speaking, neither aim to, nor credibly exercise, political power in any recognizable meaning that we can attribute to the notion. This is precisely what we find in global politics. From NGOs to transnational public and private bodies that issue standards and regulations, to the various UN agencies and the pillars of the international economic order such as the IMF and the WTO, the array of characteristics displayed by the institutions in question cannot be fully captured by traditional ideas concerning the exercise of political power. Many such institutions do not claim a right to rule, most cannot really attach penalties to their commands, the vast majority make no claim to exclusive jurisdiction, while even those institutions that come close to claiming a right to rule and attach some form of enforcement mechanism to their rulings do not rely on the use of coercion or, at least, do so in a very decentralized and/or indirect fashion. It would thus be surprising if exactly the same standard of legitimacy applied across all these types of institutions and if that standard were to be the demanding one we attach to more traditional exercises of political power, as we experience them in domestic political societies. However, we routinely speak of the legitimacy of such institutions, and we judge them from a moral and political point of view. While these institutions have different constituencies, different goals and different ways of advancing such goals, we nonetheless portray them as legitimate or illegitimate. Of course, it is entirely possible that, when describing these institutions as legitimate or illegitimate, we may be using entirely different concepts altogether. It may be the case that our use of language is simply loose in this respect. However, it is also possible that the very concept of legitimacy is broader than the democratic account suggests alone and that to require every institutional form at the global level to be governed democratically is, simply put, not very useful or appropriate.

As we have initially stated, we are broadly sympathetic to some of the concerns raised by this critique of the democratic account. We also share with Buchanan and Keohane the goal of achieving a more encompassing and, at the same time, a more general understanding of the concept of legitimacy, one that is flexible enough to capture the wide array of institutional forms that populate global governance (more on this below). Nonetheless, we want to conclude this section by making a distinction and by explaining why such a distinction invites caution when it comes to the demise of the democratic model of legitimacy applied to global governance institutions. The distinction is, roughly put, one between democratic institutional forms, on the one hand, and democratic values and ideals on the other. As examples of the former, one can think of the different shapes that the majority principle can take, or of the role of parties in the democratic process. As examples of the latter one can think of political equality, accountability, public deliberation, self-determination and political autonomy. Needless to say, the distinction is not meant to be sharp. Furthermore, it is abundantly clear that the two ideas are intimately related. Yet, it is also patently clear that the two are not one and the same thing. Democracy as an institutional form has been articulated and interpreted in several different and historically contingent ways (see Held, 2006). The same goes for democratic values and ideals. What does this tell us? It tells us that to discuss the appropriateness of democracy as a standard for the legitimacy of global governance institutions is, at least in one important respect, an open-ended exercise in which the choice of target seems to matter as much as the content of one's arguments.

The distinction between the values and ideal of democracy and the institutional forms in which such values and ideals can be embedded suggests, in our view, that the democratic approach is potentially more flexible than many of its critics seem to suggest. For example, even if we do not think that a specific global governance institution should be organized according to the majority principle, we could argue that its governance should be inspired by broadly democratic values and ideals by stressing the importance of transparency and accountability, or the fact that those that are affected by its decisions should have their voices heard. This is something that Buchanan and Keohane (2006) clearly acknowledge when they refer to the idea of ‘broad accountability’ as a key component of the legitimacy of global governance. Of course, broad accountability cannot be considered equivalent to a majoritarian account of democracy (Buchanan, 2010: 93). However, there is no reason to equate the democratic approach to a specific, majoritarian, model. Rejecting the latter, while plausible, does not allow us to assess conclusively the suitability of the former.

Moreover, just as a democratic country can embody a diversity of types of public institutions, which function according to different conceptions of legitimacy, there is no reason that this could not also be true for global democracy. The argument that institutional types vary is not an argument per se against assigning a role to democratic values at the global level. The ideal of global democracy is compatible with a diversity of types of public institutions that could be evaluated according to normative standards that are not institutionally democratic but still congruent with democratic values and ideals. The latter picture mirrors what many liberals think is the role of conceptions of justice at the domestic level. Conceptions of social and distributive justice are not meant to apply to institutional forms within civil society (nor, for that matter, to all public institutions), and yet they constrain and shape the evaluative criteria that we use to assess such institutions.

Whether these comments wholly rescue the democratic account is something that we cannot settle here. However, we do believe that the rejection of specific institutional instantiations of the democratic model should not necessarily be translated in the rejection of robustly and recognizably democratic values and ideals to be used as benchmarks for institutional evaluations. This is a point worth stressing. The complexity of global governance certainly cautions us against a one-size-fits-all approach. Nonetheless, there is no reason to believe that this is the only option that is open to a democratic approach to the legitimacy of global governance institutions. In the long run, the values and ideals of democracy may still have a part to play in the normative assessments of global governance institutions.

3 The Virtues and Problems of the Meta-Coordination View of Legitimacy

In the first two sections of this chapter, we have critically engaged with the state consent view of legitimacy and with the democratic account. The former is both morally and empirically implausible. The latter fares better, yet we have reason to believe that it too faces problems, at least if it is interpreted too narrowly. In this section, we discuss a recent attempt by Allen Buchanan (2013) to put forward an alternative to the aforementioned traditional accounts of legitimacy. Buchanan aims to provide a general account of institutional legitimacy. He calls this account the meta-coordination view. His analysis starts from two observations. The first one concerns what he calls the ‘distinctive practical role of legitimacy judgments’; that is, the fact they are necessary to solve meta-coordination problems. Meta-coordination problems refer to attempts to converge on (normative) public standards that institutions are required to meet in order to be accorded the relevant standing that they need to function effectively (2013: 178). The second concerns the type of conceptual space that our solutions to coordination problems should occupy. In order to be legitimate, we should require these solutions to be in-between two poles: mere advantage compared to a non-institutional benchmark is not enough, and yet full justice and perfect efficiency are simply too much. Between these poles lies our ability to respect institutions normatively and to take their directives as providing, at the very least, weighty reasons to comply. In this framework, legitimacy is clearly a weaker notion than justice and we can give standing to institutions that we do not find to be fully just.

While providing a conceptual location for legitimacy is important, it is of course not conclusive, since, as Buchanan recognizes, there is likely to be more than one set of criteria that satisfy the requirement of being better than non-coordination and less than full justice or optimality. Furthermore, some are bound to be sceptical of the idea that we can confer normative standing on an institution that is not fully just. Buchanan addresses both problems. He provides a set of what he calls variable criteria in order to narrow down the potentially unlimited number of solutions to coordination problems that we can describe as legitimate (2013: 188–90), and, at the same time, he puts forward what, at least in our view, are good reasons to allow institutional standing and full justice to diverge in many circumstances (2013: 180–3).

The criteria suggested are (1) good or at least not seriously tainted origins; (2) the reliable provision of the goods the institutions are designed to deliver (assuming reasonably favourable circumstances); (3) institutional integrity or the match between the institution's justifying aims and performance; (4) the avoidance of serious unfairness; and (5) the accountability of the most important institutional agents (2013: 189). These criteria should not be understood as necessary and/or sufficient to establish the legitimacy of an institution. Rather, they are to be understood as ‘counting principles’ the satisfaction of which should be seen as a ‘good-making’ feature of our legitimacy assessments. The reasons why legitimacy should be understood both as a weaker normative requirement than justice and constitute an appropriate benchmark to bestow standing on an institution are broadly connected to the idea that the best can be the enemy of the good – many institutions can provide the distinctive benefits they were designed to provide without excessive and undue costs even when they are not fully just. More specifically, Buchanan highlights how (1) it is unreasonable to expect agreement on what full justice requires and easier to converge on what we should consider to be the worst injustices; (2) in the absence of functioning institutions, what justice requires is often indeterminate because non-institutionalized moral thinking cannot be fully specific or action guiding; (3) justice may not be attainable in the here and now but more often than not will require the existence of functioning institutions in order to make progress towards what justice requires.

In what follows we assess the meta-coordination view. We believe that the position has several important positive features. At the same time, we contend that it also has some drawbacks that call for reflection on its actual potential to deliver the theoretical benefits that it claims to provide. The benefits of the meta-coordination view pertain to what we will call synchronic and diachronic flexibility. Its main drawback lies in what we will call latent indeterminacy. As it is often the case, what is good about something also marks out its limitations. The meta-coordination view is no exception to this general rule: the flexibility that allows it to adapt to the complexity of the current system of global governance has a theoretical price in terms of its ability to elicit determinate legitimacy assessments.

Why do we find the meta-coordination view attractive? Its main virtue is its flexibility, which is both synchronic and diachronic. Synchronically, the position is commendable because, by considering the criteria of legitimacy as variable counting principles, it allows us to adapt our specific conception of legitimacy to different types of institutional structures. If, following Rawls (1971/1999), we accept that the principle for a thing depends on the nature of that thing, then this is no small advantage. For example, it allows us to model our specific conception of legitimacy to different forms of institutions, which have radically divergent ways of operating. To illustrate, many global governance institutions have a technical nature; they fix standards for certain specific types of activities and create the conditions for lower transaction costs in the domains that they oversee (for instance, the International Standards Organisation, the International Maritime Organisation and the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers). For these institutions, it is plausible to think of institutional integrity (i.e., the degree to which they are able to accomplish the task(s) that they were created to perform) as going a significant way towards establishing their legitimacy, without consent or institutionally democratic requirements entering the frame. This is especially the case if we reject the idea that legitimacy is, necessarily, concerned with the establishment of a moral power (i.e., the power to impose duties), and we allow legitimacy assessments to be more widely construed as the establishment of some form of respect for institutional authority or standing (more on this below). Second, the position allows us to do this in a way that is, in our view, theoretically ecumenical. Insofar as it provides space for both deontological and teleological considerations and, at the same time, takes into account both institutional processes and outcomes, the view provides a unified form of normative assessment that tries to keep together the most important properties and benchmarks that we intuitively connect to legitimacy assessments.

The implications of such theoretical flexibility and overall ecumenical character are even more important if we think about the current state of global politics. In a world where many important international institutions and regimes are gridlocked (see Hale et al., 2013) the flexibility of the meta-coordination view allows us to be pragmatic without abandoning some our most stringent normative commitments. It allows us to understand, for example, that the benefits that we can, in principle, expect for solving specific coordination problems may be great enough to ensure we have principled reasons to relax the demandingness of the normative requirements that apply to institutional evaluations. This could be an advantage in two respects that are, in our view, morally significant. First, and most importantly, it could allow us to avoid serious harm, and harm that would in all likelihood fall on the weakest and most vulnerable people in the world, by cautioning us not to ask what is not achievable in the immediate future. Second, the meta-coordination view tries to avoid being, to paraphrase Rawls (1996), political in the wrong way. Our desire to relax the normative standards we apply to institutional structures is internal to the very idea of legitimacy, and reflects the complexity of our institutional and political landscape – not the surrender of our normative aspirations. But the meta-coordination view is also diachronically flexible. It allows us to recognize that, as circumstances change and, hopefully, become more favourable to progress towards what justice requires, we can gradually expect more from our institutions. Progress over time and according to circumstances keeps together the moral tension between more just arrangements and the reality of our present political condition.

However, as we have mentioned above, for all that is significant about the flexibility of the meta-coordination view, its flexibility has a price. The price, quite simply, is that, as it stands, it does not yet provide precise enough guidance. While Buchanan's broad position is, as we will see shortly, progress compared to some of the most influential accounts of the legitimacy of global governance institutions and public international law, it still needs to be further developed in order to provide concrete help in assessing existing institutional forms in global politics.

To see why Buchanan's view is progress, consider the Razian approach, which has recently been applied to public international law by John Tasioulas (2010). According to Joseph Raz:

[T]he normal way to establish that a person has authority over another person involves showing that the alleged subject is likely better to comply with reasons which apply to him (other than the alleged authoritative directives) if he accepts the directives of the alleged authority as authoritatively binding and tries to follow them, rather than by trying to follow the reasons which apply to him directly.

Raz refers to the latter as the Normal Justification Thesis (NJT). Roughly put, in the Razian picture of the legitimacy of authority, authority is bestowed to the extent that compliance with institutional directives gives those subject to the institution a better chance of acting rightly than does relying on private judgment alone. However, what the Razian account does not seem to provide is a way to recognize the specific conditions that should be met to reasonably believe that an institution realizes the NJT (see Lefkowitz in this volume). Lacking a more definite account of how the NJT can be satisfied hampers our ability to ascertain whether concrete institutions are to be judged as legitimate or not. It is fair to say that, without such an account, the Razian view seems to be almost completely silent about the content of legitimacy assessments. While, in our view, Buchanan's and Raz's accounts are broadly compatible, it should be clear that the meta-coordination view takes us further along the path that goes from the abstract exercise of developing the concept of legitimacy to the concrete assessment of specific institutions by providing a set of easily recognizable standards or criteria of legitimacy.

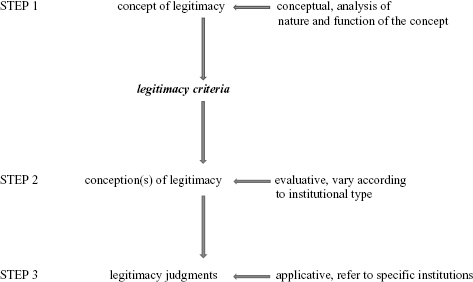

Nonetheless, some may also argue, as we do, that the meta-coordination view replaces one form of indeterminacy with another: we may have a framework to generate the appropriate types of reasons and criteria to recognize legitimate institutions, but we seem to lack a clear picture for when and how such reasons apply to different institutional types. To see why, it is useful to conceive concrete legitimacy appraisals as the result of three theoretical steps (see figure 1). The first step is the development of a concept of legitimacy, where a view of the nature and function of the very idea of legitimacy are elaborated. The second step takes us from the concept of legitimacy to different conceptions of legitimacy. Conceptions of legitimacy provide relatively abstract evaluative standards that, at least in the position we have advocated here, and which is consistent with Buchanan's view, depend on the features of the institutions we are evaluating. The third and final step gets us from a given conception of legitimacy to a judgment pertaining to a specific institution. Given our conception of legitimacy, can institution X be considered as legitimate?

Buchanan's view takes us further along the process of forming legitimacy assessments for specific institutional types and for concrete institutions. It does so by developing, as we have seen, a list of what Buchanan calls legitimacy criteria. Such criteria, understood as counting principles or good-making features of an institution, allow us to create a bridge between the concept of legitimacy and the different conceptions that will apply to different institutional types. However, while the criteria of legitimacy provided by Buchanan are useful and allow us to make progress, we still face a potentially strong form of indeterminacy given the latitude that the meta-coordination view permits. More specifically, what seems to be missing is an account of how exactly we can go from the standards of legitimacy (the variable criteria) to a specific conception of legitimacy that applies to a specific institutional type. Given that such criteria are to be understood simply as ‘counting principles’, which criteria are more salient for which type of institution? Even assuming agreement on the fact that the criteria of legitimacy suggested by Buchanan are correct (something we find plausible), there is bound to be significant disagreement about which criteria are more important for different types of institutions. For instance, should we give more prominence to the fact that institutions should not have tainted origins if the institution itself uses coercive means to ensure compliance with its directives? Should accountability become more important as the interests that are affected by an institution become more significant? In the same way, developing the precise meaning of the variable criteria provided by the meta-coordination view is going to be subject to interpretation, and relies on the understanding of the domain over which an institution operates, as well as its features. Here too, more guidance is needed to ascertain how this interpretive exercise should be conducted. For example, how are we to understand the ‘avoidance of serious unfairness’ in different contexts such as the setting of technical standards and international economic governance?

Asking the meta-coordination view for more guidance may strike the reader as an unfair request. Perhaps, the reader will add, we are asking something that theory alone cannot provide. Perhaps the only way to be more clearly action-guiding is to allow theory to be complemented by historical and sociological argument in order to put forward more specific proposals. Furthermore, once we have accepted that conceptions of legitimacy are linked to the type of institution we are considering and the context in which such institutions operate, then to give guidance cannot mean to provide a formula for each possible institutional type. These are fair points and, to the extent that we can accept them, our criticism of the meta-coordination view should be seen more as an opportunity for further research rather than an open challenge to its validity or desirability. In our view, what is needed, is a framework for generating conceptions of legitimacy. It should be one that provides us with grounds to assess the relative importance and the correct way of interpreting the legitimacy criteria developed by the meta-coordination view, as it applies to some of the main institutional types (i.e., the modern state, major global governance institutions within the economic sphere, transnational institutions which have mainly coordination functions with respect to technical standards, human rights institutions, etc.). Providing this type of framework is no easy task. And it may very well be the case that more empirically informed research is required to make progress. For example, progress could require a large-scale project that analyses the empirical features of a large number of specific global governance institutions to retrieve any generalizable conclusions that pertain to their legitimacy given their domain of action and the type of directives that they generate. Nonetheless, we hold that providing such a framework is an urgent priority if the Buchanan view is to be fully compelling and if it is to be adopted as an important guide for the evaluation of legitimacy of global governance institutions.

4 Conclusion

While the accounts of legitimacy explored in this chapter have different strengths and weaknesses, we have argued that state consent theory is both conceptually weak and a poor fit to the complexity of contemporary global governance; that the democratic theory of legitimacy, although more robust than state consent theory in many respects, too often seeks an inappropriate one-size-fits-all solution to institutional diversity and is too abstract to provide precise judgments of legitimacy in relation to particular organizations; and that the meta-coordination view, while it has distinct advantages of providing greater flexibility and adaptability to the diversity of global governance institutions, is vulnerable to indeterminacy. In a robust general theory of the legitimacy of global governance institutions, we think that elements of both the democratic and meta-coordination views may have a qualified role, but this theory is far from available at the present time.

The case for defending democratic ideals remains very strong in the context of severe existential threats and permanent minorities (perhaps, more accurately, substantial majorities on many issues) effectively excluded from the global and economic political system. Severe global challenges generate equality of stakes that democracy, appropriately embedded, could legitimately address in the long term. Likewise, suitably developed, democracy provides the means to address the problem of minority exclusion and to develop accountability mechanisms that are broadly inclusive. After all, democracy is a system of ideals and practices that seeks to ensure that regulatory structures and rule sets are accountable in the public domain. Yet, in the short term, the meta-coordination view provides important signposts and stepping stones to resolving legitimacy queries which inevitably arise under imperfect political circumstances. A general theory of legitimacy, accordingly, would seek to combine these two approaches.

References

- Archibugi, D., Archibugi, M. and Marchetti, R., eds. 2011. Global Democracy: Normative and Empirical Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bodin, J. 1992. On Sovereignty, trans. and ed. J. H. Franklin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buchanan, A. 2010. ‘The Legitimacy of International Law, Democratic Legitimacy and International Institutions’, in S. Besson and J. Tasioulas, eds., The Philosophy of International Law, 79–96. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buchanan, A. 2013. The Heart of Human Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buchanan, A. and Keohane, R. 2006. ‘The Legitimacy of Global Governance Institutions’, Ethics & International Affairs 20(4): 405–437.

- Cassese, A. 1995. Self-Determination of Peoples: A Legal Reappraisal. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Christiano, T. 2008. The Constitution of Equality: Democratic Authority and Its Limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Christiano, T. 2010. ‘Democratic Legitimacy and International Institutions’, in S. Besson and J. Tasioulas, eds., The Philosophy of International Law, 119–138. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Christiano, T. 2011. ‘Is Democratic Legitimacy Possible for International Institutions?’, in D. Archibugi, M. Koenig-Archibugi and R. Marchetti, eds., Global Democracy, 60–95. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Christiano, T. 2012a. ‘The Legitimacy of International Institutions’, in A. Marmor, ed., The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Law, 380–394. New York: Routledge.

- Christiano, T. 2012b. ‘Authority’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. E. N. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/authority/.

- Crawford, J. and Marks, S. 1988. ‘The Global Democracy Deficit: An Essay on International Law and Its Limits’, in D. Archibugi, D. Held and M. Köhler, eds., Re-imagining Political Community, 72–90. Cambridge: Polity.

- Estlund, D. M. 2009. Democratic Authority: A Philosophical Framework. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fishkin, J. 1991. Democracy and Deliberation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Hale, T., Held, D. and Young, K. 2013. Gridlock: Why Global Cooperation is Failing When We Need It Most. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hampsher-Monk, I. 1993. A History of Modern Political Thought: Major Political Thinkers from Hobbes to Marx. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Held, D. 1995. Democracy and the Global Order. Cambridge: Polity.

- Held, D. 2002. ‘Law of States, Law of Peoples’, Legal Theory 8(1): 1–44.

- Held, D. 2004. Global Covenant: The Social Democratic Alternative to the Washington Consensus. Cambridge: Polity.

- Held, D. 2006. Models of Democracy, 3rd edn. Cambridge: Polity.

- Held, D. 2014. ‘The Diffusion of Authority’, in T. Weiss and R. Wilkinson, eds., International Organization and Global Governance, 60–72. London: Routledge.

- Held, D. and McGrew, A. 2007. Globalization/Anti-Globalization, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Polity.

- Held, D., McGrew, A., Goldblatt, D. and Perraton, J. 1999. Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hinsley, F. H. 1986. Sovereignty, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jackson, R. J. 1990. Quasi-States: Sovereignty, International Relations and the Third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Krasner, S. 1999. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Marchetti, R. 2008. Global Democracy: For and Against. New York: Routledge.

- Offe, C. and Preuss, U. 1991. ‘Democratic Institutions and Moral Resources’, in D. Held, ed., Political Theory Today, 143–171. Cambridge: Polity.

- Peter, F. 2010. ‘Political Legitimacy’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. E. N. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/legitimacy/

- Peter, F. 2008. Democratic Legitimacy. New York: Routledge.

- Rawls, J. 1971/1999. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rawls, J. 1996. Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Raz, J. 1986. The Morality of Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rischard, J. F. 2002. High Noon. New York: Basic Books.