Nelson, Willie

(b. 1933) COUNTRY MUSIC SINGER.

Willie Hugh Nelson was born in Fort Worth, Tex., on 30 April 1933 and was reared in the little central Texas town of Abbott, where he was exposed to a wide variety of musical influences. He grew up singing gospel songs in the Baptist church but also played in honkytonks all over the state. Before he was a teenager, he began playing guitar in the German-Czech polka bands in the “Bohemian” communities of central Texas; he listened to the country music of Bob Wills, Lefty Frizzell, and Floyd Tillman, but he was also an avid fan of jazz and vintage pop music. All of these forms clearly influence the music he plays today.

Despite his skills as a guitarist and unorthodox singer (with his blues inflections and off-the-beat phrasing), Nelson’s ticket to Nashville came through his songwriting. In 1960 he moved to Nashville, where he became part of an important coterie of writers, which included Hank Cochran, Harlan Howard, and Roger Miller. Nelson made a major contribution to country music’s post–rock-and-roll revival with such songs as “Funny How Time Slips Away,” “Hello, Walls,” “Night Life,” and “Crazy,” all of which were successfully recorded by other singers.

Recording for RCA Victor in the mid-1960s, Nelson became widely admired by his colleagues as a “singer’s singer,” but he did not achieve the stardom that he sought. In 1972 he relocated to Austin, Tex., where he became part of an already-thriving music scene that was strongly oriented toward youth who had grown up listening to rock and urban folk music. Nelson made a calculated attempt to appeal to this audience by changing his physical image: he let his hair grow long, grew a beard, and began wearing a headband, an earring, jeans, and jogging shoes (a striking contrast to the well-groomed, middle-class appearance he had affected during his Nashville years). He also publicized himself with his huge annual “picnics,” first held in Dripping Springs, Tex., in 1972 and 1973 and later staged in a variety of Texas communities, usually on the Fourth of July. These festivals were intended to bridge the gap between youth and adults, while bringing together varied lifestyles and musical forms. The picnics, however, soon lost their appeal to older people or to traditional country fans and instead became havens for uninhibited youth and for musicians who seemed most comfortable with a country-rock perspective.

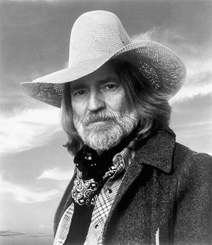

Willie Nelson, country music singer, 1980s (Columbia Records, New York)

After winning the youth audience, Nelson then captured the adult market. In 1975 he recorded a best-selling album called The Red Headed Stranger, and one song from the album, Fred Rose’s “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” became the No. 1 country song of the year (it is ironic that the first superhit recorded by this master songwriter was a song written by someone else). Nelson’s ascent to superstardom and his building of a large and diverse audience were accomplished without significant departures from his traditional style. Indeed, his repertoire became even more traditional as he reached back to the performance of older gospel, country, and pop songs. No one in American music performed a more eclectic sampling of songs. He also preserved his unorthodox style of singing and sang over a rather spare and uncluttered scheme of instrumentation, which was dominated by his own inventive, single-string style of guitar playing.

Nelson has won many country music awards since the mid-1970s, including the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award in 1979, but his appeal has extended far beyond the country music world. Nelson has collaborated with a diverse array of stars from various genres of music, including Toby Keith, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Bonnie Raitt, Merle Haggard, and Paul Simon.

Nelson has received favorable reviews for his roles in several movies, such as The Electric Horseman (1979) and Wag the Dog (1997). Nelson also played Uncle Jesse in the 2005 cinematic remake of The Dukes of Hazzard. He has been feted constantly by the American media, and he has entertained often at political events, including the Democratic National Convention in 1980, during the Carter presidency. Few country singers have enjoyed such broad exposure. In addition to performance, Nelson has invested his energies in charity work, such as establishing the Farm Aid concert in 1985 and organizing a concert in 2005 for the victims of the Indian Ocean earthquake with UNICEF. Nelson continues to tour, and during breaks from touring he spends time at his Pedernales estate outside of Austin, Tex.

BILL C. MALONE

Madison, Wisconsin

Willie Nelson, The Facts of Life and Other Dirty Jokes (2002), Willie Nelson: Teatro (2001); Willie Nelson and Bud Shrake, Willie: An Autobiography (1992); Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (1974); Al Reinert, New York Times Magazine (26 March 1978); Clint Richmond, Willie Nelson: Behind the Music (2000); Lola Scobey, Willie Nelson (1982).

Neville Brothers

RHYTHM-AND-BLUES, SOUL, AND FUNK SINGERS.

The Neville brothers—Art, Aaron, Charles, and Cyril—are likely the best-known musical family to come out of New Orleans in recent decades. Both as individuals and as a group, they have made crucial contributions to several genres of popular music. Building on early careers in the fields of R&B and soul, the brothers were instrumental in defining the funk sound of the 1970s by reconnecting New Orleans music with its Caribbean and Afro-diasporic roots.

Art, Charles, and Aaron were born in 1937, 1938, and 1941, respectively. Music and dance were central in their upbringing. Although not a musician, their father, Arthur, was close to singer-guitarist Smiley Lewis, and their mother, Amelia, had performed in a dance team with her younger brother, George Landry. Known to his nephews by the nickname “Uncle Jolly,” Landry was a gifted piano player who, like their father, traveled the world as a merchant seaman.

As they grew up, Art learned to play barrelhouse-style piano, Aaron built his skills as a vocalist by singing gospel music, and Charles studied the saxophone. The brothers played in various groups, and by the time Cyril was born in 1948, Art was well on his way to making a name for himself in the local music scene. His group, the Hawketts, recorded a song called “Mardi Gras Mambo” for radio DJ Ken “Jack the Cat” Elliot. The record, released by Chess in 1954, was widely popular and quickly became an enduring staple of the Carnival season, although the performers saw none of the profits.

Charles, who also played with the Hawketts, dropped out of school at age 15 to tour as a tenor saxophone player with Gene Franklin’s House Rockers. R&B star Larry Williams took several of the brothers under his wing and, along with producer Harold Battiste (who ran the New Orleans office of L.A.-based Specialty Records), helped Art develop as a solo artist. He cut several sides for Specialty, including “Cha-Dooky-Doo” and “Ooh-Whee Baby,” before moving to the Instant label in 1962, where he had a local hit with the ballad “All These Things.”

Aaron began recording songs for local label Minit in 1960 and was working as a longshoreman when he had a hit record with the Allen Toussaint–produced ballad “Tell It Like It Is” in late 1966. The song showcased his impressive falsetto range and spent 17 weeks on the BillboardR&B charts, peaking at No. 1 and earning him a gold record in the early part of 1967. Unfortunately, this success overwhelmed the start-up independent Par-Lo record label, which soon folded. With few royalties arriving, Aaron went on the road, backed by his brother Art’s group, to exploit his hit record.

Art Neville and the Neville Sounds was a large group, which included, among others, Art, Aaron, and Cyril Neville on percussion and vocals. The group played regularly at the Nite Cap until 1967, when Art Neville and the rhythm section departed, forming a new four-piece group, which would become known as the Meters, releasing a string of albums in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Aaron, Cyril, and other remaining members formed another group, called the Soul Machine. Charles, meanwhile, had his musical career interrupted by a three-and-a-half-year stint in the state prison at Angola, after being arrested on minor drug charges. Upon release, he moved to New York City, where he found work playing with a white soul group, Tony Ferrar and the Band of Gold.

By 1976 George “Chief Jolly” Landry had become centrally involved in the city’s Mardi Gras Indian scene and teamed up with the four brothers in 1976 to record the Wild Tchoupitoulas album for Island Records. The effort marked the beginning of a new era in the brothers’ careers, with New Orleans Carnival and parade music becoming even more central than before. Soon afterward, they formed the Neville Brothers, which has been their musical home ever since.

After building their local reputation, the brothers secured a record deal with Capitol, releasing their eponymous debut in 1978. The eclectic album was poorly promoted, and the brothers soon moved to A&M Records, where they released Fiyo on the Bayou in 1981. They documented one of their frequent appearances at New Orleans bar Tipitina’s on 1984’s Live Nevillization and won a Grammy for their song “Healing Chant” from their 1989 album Yellow Moon. Through most of the 1990s, they continued to record for A&M, moving to Columbia late in the decade, where they released Valence Street in 1999.

MATT MILLER

Emory University

Jason Berry, Jonathan Foose, and Tad Jones, Up from the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music since World War II (1986); Art Neville, Aaron Neville, Cyril Neville, and Charles Neville, The Brothers: An Autobiography (2000).

New Orleans Sound

New Orleans has played a central role in the development of American—and especially African American—popular music and dance styles. Although jazz remains its most famous product, the city has made key contributions to rhythm and blues, rock and roll, soul, funk, and rap. Within the context of the United States, New Orleans’s uniquely diverse and layered history of cultural intermixture has helped the city to maintain a central presence in the national popular music culture, even as it remains on the margins of the corporate music industry.

Settled by the French in 1718, Louisiana depended heavily upon enslaved black labor, which in its early decades was extracted largely from the Senegambia region. A high level of cultural cohesion and continuity among these slaves, combined with the relatively tolerant attitude of the French, contributed to the continuation and adaptation of West African–originated cultural practices in musical and other contexts, which in turn significantly influenced the development of a creolized culture in the colony generally.

The numbers of slaves and free blacks grew under a brief period of Spanish control and were augmented by refugees from the revolutions in San Domingo and Cuba. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the beginning of American control, the city became an important commercial center heavily invested in the slave trade. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, large numbers of enslaved and free blacks from New Orleans and its hinterlands regularly gathered in city markets to buy and sell produce and to engage in a variety of leisure activities, including music and dance. The most famous of these was a large field off of Rampart Street, which became known as Congo Square. The gatherings there had largely ended by the Civil War, but their mythic reputation as a manifestation of African-originated cultural practices has persisted.

The assumption of control by the United States introduced several important changes. The full implementation of a more restrictive Anglo-Protestant approach to race and social control would take more than a century, but an influx of English-speaking Americans began to alter the character of the city almost immediately. Blacks from the surrounding Delta region flowed into the city, their numbers surging after the Civil War and Emancipation. These migrants generally settled in the less desirable parts of the Uptown area, upriver from the French Quarter; French-speaking blacks remained tied to an area down-river called Downtown, which included neighborhoods like Faubourg Tremé. The French-speaking blacks enjoyed traditions of education, mutual aid, and formal musical instruction, but the American blacks brought with them a more rural musical sensibility rooted in blues and string band music. The interaction of these two distinct but compatible musical traditions formed the basis for the emergence of jazz in the final decades of the 19th century.

Charles “Buddy” Bolden, a black barber, cornetist, and bandleader from Uptown, is widely credited with the introduction of jazz as it is generally understood—highly syncopated ensemble dance music in which improvisation plays a central role. Bolden failed to reap the full rewards of what he had introduced in the 1890s—he never recorded and retired from playing relatively early—but his efforts laid the groundwork for the development of a new direction in New Orleans music. Like many of his contemporaries, Bolden was able to draw from a rich array of environmental musical influences that existed in New Orleans, which ranged from military bands to the cries of street vendors hawking their wares.

Jazz developed in diverse forms and contexts. Building upon the rag-time genre, piano players like Tony Jackson and Jelly Roll Morton entertained patrons with propulsive dance music in various establishments of the Storyville tenderloin district, which operated legally between 1897 and 1917. Other venues—including barrooms, ballrooms, steamboat excursion rides, dances of all kinds, and outdoor gatherings—called for larger and louder music, and the city soon saw the proliferation of the five- to seven-piece ensemble groups playing “hot” jazz music characterized by chaotic-seeming collective improvisation.

By the time the secretary of the navy ordered the closing of Storyville in 1917, jazz was already being disseminated throughout the country. River towns like Memphis, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Chicago were a natural destination for New Orleans musicians, and several established themselves in New York. Some players, like the early cornet innovator Bunk Johnson, remained in the Gulf South, while others, like Joseph “King” Oliver and, later, his young protégé Louis Armstrong, struck out for greener pastures upriver. Chicago became a home away from home for many New Orleans musicians, who by leaving their native city avoided some of the effects of Jim Crow segregation.

In the closing decades of the 1800s, large numbers of Italians and Irish had immigrated to New Orleans, and these groups also contributed to the ranks of early jazz artists and audiences. The first band to make a jazz recording was the white Nick LaRocca’s Original Dixieland Jazz band in 1917, which produced the first million-seller for RCA Victor. Other important figures in the development of New Orleans jazz in the 1910s and 1920s include cornetist Freddie Keppard, clarinetist Sidney Bechet, and bandleader George Vital “Papa Jack” Laine.

The combined effects of the Depression and World War II severely curtailed the ability of New Orleans musicians to record, although a vital vernacular music culture persisted. The city’s Carnival (the largest in the United States) has helped to foster a collective musical sensibility and has presented opportunities for celebration, self-expression, and the occupation of public spaces, which blacks rarely failed to exploit. So-called Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs and Carnival societies like the Zulus hire brass bands for members’ funerals, which often feature the now-familiar mixture of somber music on the way to the graveyard followed by celebratory and expressive dance music after interment. In a tradition that dates back to the 19th century, parades with brass bands are usually accompanied by a “second line,” an informal contingent of spectator-participants who dance and accompany the band on percussion instruments, including tambourines, glass bottles, and other improvised materials. Musical techniques derived from street parade music have formed a crucial component of the city’s distinctive musical sensibility over the last century.

The music of the Mardi Gras Indians—groups of working-class blacks organized along neighborhood lines who parade in elaborate Native American–inspired costumes during Carnival season—has also exercised significant influence over popular music forms emanating from New Orleans in the last century. The rehearsals and public appearances of these groups are characterized by music making that relies heavily upon percussion ensemble and the collective performance of chanted lyrics in a call-and-response format.

During the postwar years, a thriving music scene developed again in New Orleans, now based around a genre known as rhythm and blues, or R&B. Bands led by Roy Brown and Dave Bartholomew were among the top acts in the city during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Working with California-based Imperial Records in the 1950s, Bartholomew produced a string of national hits for the amiable piano player and singer Antoine “Fats” Domino, who remains one of the most popular artists to emerge from New Orleans in any time period. A host of other talented R&B artists came out of the city in these years, including Smiley Lewis, Jewel King, Lloyd Price, and the teen piano sensation James Booker, among others. In the 1950s, L.A.-based labels like Imperial and Specialty Records mined the New Orleans scene for marketable talent and also sent performers there to record with expert musicians and arrangers.

The city’s relationship with the emerging rock-and-roll genre was relatively brief but crucial in terms of the influence that New Orleans–based studio musicians, like drummer Earl Palmer and saxophone player Alvin “Red” Tyler, exercised over the developing rhythmic sensibility of the genre. With artists like Huey “Piano” Smith, Jimmy Clanton, and others, Ace Records released many pioneers of the style and drew “Little” Richard Penniman to the city, where he made his early recordings in 1955 and 1956 and hired the band the Upsetters to back him on the road.

The Dew Drop Inn, a combination bar and hotel where the city’s top black performers and sidemen shared the stage with female impersonators and burlesque dancers, was a musical hot spot during these years, along with other clubs like the TiaJuana and the Caldonia. Among the many talented performers from this period, Roy “Professor Longhair” Byrd is one of the most celebrated, although he was only moderately successful during his peak of recording activity in the 1950s. Longhair flavored his barrelhouse piano style with Caribbean accents and bouncing left-hand rhythms, producing a style that, for many, would come to represent the city’s musical identity.

During the 1960s New Orleans was the home of a thriving independent music scene, with producers like Wardell Quezergue and Allen Toussaint frequently using Cosimo Matassa’s recording facilities and studio band. Nothing can quite match the success of Fats Domino in the 1950s, but the 1960s saw a string of national hits emerge from the city by the likes of Chris Kenner, Robert Parker, the Dixie Cups, Johnny Adams, and Irma Thomas, among others. The city’s musical reputation attracted international stars like Paul McCartney and Robert Palmer, who both recorded there during the mid-1970s.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, New Orleans–based artists like the Meters and Dr. John increasingly began to draw inspiration from the parade and Carnival traditions of the city. Aided by the inauguration of the annual Jazz and Heritage Festival, the city experienced an R&B revival of sorts in the 1970s, reviving the career of Professor Longhair, among others. Other dimensions of the city’s musical heritage also reached wider audiences: several Mardi Gras Indian groups released albums during the 1970s, and the brass band form began a revival, with groups like the Dirty Dozen, which broke new ground by infusing the form with a swinging funkiness. Groups like Re-Birth, the Hot 8, and others continue to produce some of the most compelling and propulsive brass band music to be heard anywhere in the United States.

The city’s musical distinctiveness continued into the rap era. A dance-oriented style called “bounce” took over the local market in the early 1990s and by the end of that decade had helped to propel artists like Juvenile into the national spotlight. However, the Katrina disaster of 2005 severely disrupted the deeply rooted traditions and cultural practices of working-class and poor black communities, a loss that will doubtlessly affect the ability of New Orleans to produce innovative forms of dance music in the future.

MATT MILLER

Emory University

Danny Barker, Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville, ed. Alyn Shipton (1998); John Broven, Rhythm & Blues in New Orleans (1988); Court Carney, Popular Music in Society (2006); Jeff Hannusch, I Hear You Knockin’: The Sound of New Orleans Rhythm and Blues (1985); Curtis D. Jerde, Black Music Research Journal (Spring 1990); Jerah Johnson, Louisiana History (Spring 1991), Popular Music (April 2000); Frederic Ramsey Jr. and Charles Edward Smith, eds., Jazzmen (1939); Michael P. Smith, Black Music Research Journal (Spring 1994); Alexander Stewart, Popular Music (October 2000).

Oliver, King

(1885–1938) JAZZ MUSICIAN.

Joseph “King” Oliver was born in or near New Orleans and became an early black jazz cornetist and bandleader. By 1900 he was playing cornet in a youthful parade band. From 1905 to 1915 Oliver became a prominent figure in various brass and dance bands and with small groups in bars and cafés. He soon gained the title “King” in competition with other leading local cornetists. In 1918 he joined a New Orleans band playing in Chicago, and by 1920 he was leading his own group there. He toured with this band in California in 1921 and, returning to Chicago the next year, enlarged it as King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. This handpicked ensemble boasted some of New Orleans’s best black instrumentalists, including Johnny and “Baby” Dodds (clarinet and drums, respectively) and Oliver’s brilliant young protégé, Louis Armstrong (second cornet). The Creole Band’s beautifully drilled performances at Chicago’s Lincoln Gardens and its tour through the Midwest created a sensation among northern musicians, and in 1923 it made the most extensive series of recordings (some three dozen) of any early jazz band.

When several members, including Armstrong, left the band in late 1924, Oliver formed a new, larger dance orchestra with saxophones, called the Dixie Syncopators. This sporadically successful orchestra, with changing personnel, played in Chicago from 1925 to 1927 and at New York’s Savoy Ballroom in 1927. Between 1926 and 1928 the orchestra made a number of recordings of uneven quality, though a few were popular hits. By 1930 Oliver’s career as a soloist had ended. From 1930 to 1936 he led a succession of small orchestras across the country, though a severe dental condition prevented him from playing. After 1936 he lived in Savannah, with an ailing heart, and spent his last year there running a fruit stand and working as a janitor in a pool hall. He died on 8 April 1938.

One of the foremost first-generation New Orleans jazz cornetists, Oliver was a central figure in the transfer of rag-time and of the black blues and gospel song from nearby rural areas to the New Orleans urban band tradition. The recordings of his Creole Jazz Band are the best and most extensive documentation of how vocal blues and instrumental ragtime were fused by emerging jazz bands into a new music of distinctively black southern origins.

JOHN JOYCE

Tulane University

Ray Bisso, Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver (2001); Lawrence Gushee, in Jazz Panorama, ed. Martin Williams (1962); Frederic Ramsey Jr., in Jazzmen, ed. Frederic Ramsey Jr. and Charles E. Smith (1939); Martin Williams, King Oliver (1960).

OutKast

RAP GROUP.

The Atlanta-based rap duo known as OutKast—composed of Andre Benjamin (known as “Dre” and, after 1999, “Andre 3000”) and Antwan “Big Boi” Patton—is one of the most successful southern rap groups and has been instrumental in focusing national attention on the “Dirty South,” the burgeoning rap music scenes and industry in Atlanta and other major southern cities. The duo has produced a series of singles and albums that have earned widespread critical acclaim, with each successive effort reaching wider audiences, and has built a reputation for eclectic and experimental rap and pop music, which nevertheless remains grounded in the environs, experiences, and cultural values of black, working-class urban southerners.

The two aspiring rappers began their collaboration while students at Tri-Cities High School in the East Point area of Southwest Atlanta, finding common ground in a preference for sharp dressing and New York rap groups like A Tribe Called Quest. Their recording career began in 1994, when they auditioned for producer Rico Wade, who worked out of his unfinished basement (called “the Dungeon”) as part of a production team known as Organized Noize. After recording the 17-year-old rappers in the Dungeon, Wade soon secured a deal for them with LaFace Records, an Arista-backed company operated by Antonio “LA” Reid and Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds, known primarily for R&B groups like TLC and Xscape.

Their first single, “Player’s Ball,” was a Christmas song set in the context of Atlanta’s “player” culture and spent six weeks at the top of the Billboard rap charts in 1993. Their debut album, 1994’s Southernplayalisticadillacmusik, featured richly textured production that was slower than most southern rap of the time and lyrics that, although still strongly oriented toward the spaces and culture of black Atlantans, rejected the hook-based approach of many southern bass rappers in favor of more complexly rendered themes and vocal performances. The album sold more than a million copies, reaching the Top 20 on the Billboard album charts and earning the group the “best new artist of the year award” from Source magazine in 1995.

In the 1996 release ATLiens, Patton and Benjamin ventured into production, efforts that resulted in the hit song “Elevators (Me and You).” The album met with widespread critical and commercial acclaim, selling more than a million and a half copies. The pair solidified their creative control by producing most of the songs on their next album, 1998’s Aquemini, which reached sales of 2.5 million copies. The album’s hit song, “Rosa Parks,” provoked a lawsuit by the song’s namesake and civil rights–era legend, which was eventually settled in the group’s favor.

The 2000 album Stankonia was a tour de force for OutKast and its label LaFace. The album sold five million copies and broke new ground as the first all-rap record to contend for the prestigious “Album of the Year” award at the Grammy awards. “Ms. Jackson” became the duo’s first No. 1 pop single, and the album won two Grammy awards out of five nominations. Subsequently, they toured as the opening act for hip-hop singer Lauryn Hill, using a live backup band and cementing their position as representatives of hip-hop music’s creative vanguard.

Following the release of Stankonia, the pair started their own record label, Aquemini Records, and in mid-2001 (a year that also saw the introduction of another venture, OutKast Clothing) Aquemini released its first record, by rapper Slimm Calhoun. OutKast released Speakerboxxx/The Love Below in 2003, which proved to be an enormous commercial, critical, and crossover success, earning the duo three Grammy awards, including “Album of the Year.” The album produced two hit singles, “Hey Ya!” and “The Way You Move.” Beginning in 2004, the pair further diversified by coproducing and starring in the $27 million film production Idle-wild, which, along with an accompanying sound track album composed by the group, was released in 2006.

OutKast’s career both contributed to and benefited from the emergence and subsequent development of Atlanta as the Southeast’s rap music capital. Hailed in Source as “the country’s newest and hottest hip-hop center” in 1994, by 2002 rap music was estimated to contribute half a billion dollars to Atlanta’s economy. Over the course of the last decade, artists and labels from the city have increasingly dominated the “Dirty South” movement, which has helped the South move from a rap music backwater to a national center of rap music production. With a career that now has run for more than a decade, OutKast remains central to Atlanta’s reputation as a center for innovative and compelling interpretations of the rap form.

MATT MILLER

Emory University

Chris Nickson, Hey Ya! The Unauthorized Biography of Outkast (2004); Roni Sarig, Third Coast: Outkast, Timbaland, and How Hip-Hop Became a Southern Thing (2007).

Parsons, Gram

(1946–1973) ROCK SINGER.

Born 5 November 1946 in Winter-haven, Fla., Gram Parsons was one of the most influential popular musicians of his generation. As a teenager, a devoted follower of Elvis Presley, Parsons performed with rock-and-roll bands from 1959 until 1963, when he joined an urban folk music group, the Shilos. After briefly attending Harvard in 1965, he joined the International Submarine Band and began drawing upon his southern background in an early attempt to synthesize country and rock. Beginning in the mid-1960s, Parsons devoted himself to what he called “cosmic American music”—essentially a dynamic combination of southern-derived styles with a solid country core.

The International Submarine Band dissolved in 1967, just prior to the release of Safe at Home, arguably the first complete country-rock album. In 1968 Parsons joined the popular folk-rock group the Byrds and, in tandem with longtime member Chris Hillman, led the band in the direction of country music. The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, released in 1969, was a landmark in the evolution of country rock. It also featured one of Parsons’s finest compositions, “Hickory Wind,” an evocative tribute to his southern childhood. Parsons and Hillman went on to organize what became the definitive country-rock band, the Flying Burrito Brothers. As a Burrito, Parsons began to deepen his vision of the South, which had first emerged with “Hickory Wind.” In his songs as well as his lifestyle, Parsons often portrayed himself as a southern country boy set adrift in the contemporary urban maelstrom. His finest song, “Sin City” (1969), was the classic statement of this theme.

After leaving the Burritos in 1970, Parsons produced little significant work until the release of his first solo album, GP, in 1973. The album featured Emmylou Harris on vocals and confirmed his mastery of the country-rock idiom. Throughout the album, the South was portrayed as an almost mythical land of stability and steadfastness.

On 19 September 1973, Gram Parsons died in Joshua Tree, Calif. An autopsy was inconclusive as to the cause of death. Several posthumous works, including Grievous Angel (1974), Sleepless Nights(1976), and Gram Parsons and the Fallen Angels—Live 1973 (1982), attest to his exceptional gifts as a singer and songwriter. Much of his work continues to inform contemporary popular music, especially in the country field. The principal carrier of his legacy since his death has been his former partner, Emmylou Harris.

STEPHEN R. TUCKER

Tulane University

Richard Cusick, Goldmine (September 1982); Ben Fong-Torres, Hickory Wind: The Life and Times of Gram Parsons (1998); Sid Griffin, Nashville Gazette (April–June 1980); Judson Klinger and Greg Mitchell, Craw-daddy (October 1976); Jason Walker, God’s Own Singer: A Life of Gram Parsons (2002).

Parton, Dolly

(b. 1946) ENTERTAINER.

Dolly Parton is often described as a contemporary “Cinderella,” a fairy tale princess, or a country gypsy—a platinum blonde heroine who escapes poverty in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains, achieves fame and fortune in Nashville and later Hollywood, and lives happily ever after. More realistically, she is a talented and creative artist and businesswoman.

Dolly Parton was born in Locust Ridge in Sevier County, Tenn., the fourth of twelve children, to Avie Lee Owens and Randy Parton. Her grandfather Owens was a minister, and her early life with family and community centered around religion and the church. She learned to love storytelling, music, and singing, as well as to adhere to a rigid Christian moral code. Her mother sang the traditional folk songs she had learned from a harmonica-playing Grandmother Owens. By the time she was five years old Parton was imagining lyrics and tunes, and by the time she was seven she had written her first song. An exceptionally intelligent child, Dolly Parton used the rich southern folk environment surrounding her to create poetry and music.

She began her singing career as a child on the Cas Walker Radio Show, broadcast from Knoxville, and she released her first record, “Puppy Love,” in her early teens. At 18, after she graduated from high school, she moved to Nashville, and, despite a difficult beginning, which she describes in her song “Down on Music Row” (1973), she became a popular recording and television partner for country artist Porter Wagoner. Together, they recorded 13 albums and won awards for Vocal Duo of the Year in 1968, 1970, and 1971. In 1967 Dolly Parton released her first solo album. She has recorded over 30 albums for Monument and RCA. She has written and recorded hundreds of her own compositions, which are usually autobiographical songs, work songs, or sentimental, moralistic ballads, often sung in a traditional country style reminiscent of the Carter Family, an authentic southern folk group that was among the first to record country music during the early 20th century.

Based upon Billboard’s year-end hit charts, among her most successful singles have been “Mule Skinner Blues” (1970), “Joshua” (1971), “Jolene” (1974), “I Will Always Love You” (1974), “The Seeker” (1975), “All I Can Do” (1976), “Here You Come Again” (1978), “Heart-breaker” (1978), “Two Doors Down” (1978), “You’re the Only One” (1979), “Baby, I’m Burning” (1979), “Starting Over Again” (1980), “But You Know I Love You” (1981), and “Islands in the Stream,” a duet with Kenny Rogers (1983). She was Female Vocalist of the Year in 1975 and 1976 and was the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year in 1978. In 1980 Billboard listed her among the top female artists in country music and Dolly, Dolly, Dolly and 9 to 5 among the top albums.

Dolly Parton, country music singer and actress, 1987 (Columbia Records, New York)

Dolly Parton achieved celebrity status by appealing to both country and pop music audiences and by entering the fields of television, film, and freelance writing. She has been featured in numerous periodicals and has appeared on the cover of Playboy (1978), the Saturday Evening Post (1979), Parade (1980), and Rolling Stone (1980). In 1976 she became the first woman in country music history to acquire her own syndicated television show, and she has since starred in several films, 9 to 5 (1981), The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982), Rhinestone (1984), Steel Magnolias (1989), and Miss Congeniality 2: Armed and Fabulous (2005). She published a book of poems titled Just the Way I Am (edited by Susan P. Shultz, 1979), wrote a novel, Wild Flowers, and published an autobiography, Dolly: My Life and Other Unfinished Business (1994). Parton and Herchend Enterprises in 1986 opened Dollywood, a theme park based on Parton’s life and located at Pigeon Forge, Tenn. It remains among the most popular vacation destinations in the South. She has also donated more than one million books to preschool children across the United States, and she provides scholarships to high school students in Sevier County, Tenn. In return, the county honored her with a life-size statue in front of the courthouse.

Parton has received numerous awards. She has received seven Grammy awards—and garnered 42 nominations—and 10 awards from the Country Music Association—with 42 nominations. She received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1984. Parton was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1996 and the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1999. That same year she joined with independent label Sugar Hill Records to create the acoustic album The Grass Is Blue. An instant favorite among critics and longtime fans, it won the International Bluegrass Music Association’s album of the year and a Grammy for best bluegrass album. She followed it with Little Sparrow in 2001 and Halos & Horns in 2002. The patriotic For God and Country appeared in 2003 and was followed by the CD and DVDLive and Well a year later. Those Were the Days from 2005 found Parton covering her favorite pop songs from the 1960s and 1970s. She has received two Academy Award nominations, first for “9 to 5,” which appeared in the film by the same name in 1982, and then in 2006 for her song “Travelin’ Thru,” which she wrote specifically for the film Transamerica. Parton was awarded the Living Legend medal by the U.S. Library of Congress on 14 April 2004 for her contributions to the cultural heritage of the United States. This was followed in 2005 with the National Medal of Arts, the highest honor given by the U.S. government for excellence in the arts.

Dolly Parton has demonstrated the strength of a southern cultural and musical background, and she retains a loyalty to her home place and her people. The lyrics she writes in songs like “Jolene,” “My Tennessee Mountain Home,” and “Coat of Many Colors” portray strong women who hail from the working-class South. Moreover, in film, television, and music, Parton herself is a country woman with stamina, intelligence, independence, and a sense of humor. She has popularized the idea that mountain women in particular are not the stereotypical hillbillies viewed in comic strips or popular situation comedies, but rather are complex, intelligent, articulate, and loving. Dolly Parton’s music and personality will have a lasting impact upon popular images of women in the South.

RUTH A. BANES

University of South Florida

Chet Flippo, Rolling Stone (December 1980); Alanna Nash, Dolly (1978); Dolly Parton, Dolly: My Life and Other Unfinished Business (1994); Playboy (October 1978); Cecelia Tichi, ed., Reading Country Music: Steel Guitars, Opry Stars, and Honky-Tonk Bars (1998); Vertical files on “Dolly Parton,” Country Music Foundation Library and Media Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Patton, Charley

(c. 1891–1934) BLUES SINGER.

Few people have had as great an impact on American music as has Charley Patton. Not only was Patton the first superstar of the blues, but many other forms of music today, such as gospel, R&B, soul, and, most particularly, rock and roll, were directly influenced by his work.

Charley was born to Bill and Annie Patton around 1891 near the central Mississippi towns of Bolton and Edwards. At an early age he had a predilection for making music, and he learned to play the guitar when still very young. But Charley grew up in a hard-working and religious farming family, and his father considered playing the guitar a sin tantamount to selling one’s soul to the devil. His father often disciplined him for playing music, but Charley continued performing ragtime, folk songs, and spirituals at picnics and parties in Henderson Chatmon’s string band, most likely for all-black audiences at first and then for whites who could afford to pay better.

In 1897, seeking to capitalize on the economic opportunities that the Mississippi Delta had begun to offer planters and day laborers, Bill Patton packed up his family and relocated north to Will Dockery’s farm. It was at Dockery Farms that Charley invested his musical ability in the burgeoning blues. A number of guitar players already lived there, and Charley began to study the raw and rhythmic blues-playing technique of Henry Sloan, eventually crafting an extraordinarily inventive style of his own, which incorporated hitting heavy bass notes and playing slide guitar with a knife.

In the 22 years that followed his arrival at Dockery Farms, Charley never completely disavowed his religious upbringing. He continually vacillated between the roles of hard-drinking, womanizing rambler and god-fearing preacher. The rambling bluesman in him won out most often, but even then he stayed relatively close to home, never traveling farther than western Tennessee, eastern Arkansas, or northeastern Louisiana to play gigs. While in Jackson, Miss., in the summer of 1927, Henry C. Spier, a white music-store owner, arranged for Charley to go to Richmond, Ind., to record. Charley spent June 14 in a Gennett Records recording studio recording 14 songs. That recording session produced some of his most celebrated work, including “Pea Vine Blues,” “Tom Rushen Blues,” and “Pony Blues,” the latter becoming an immediate “race record” hit. Later in that year, Charley traveled to Grafton, Wis., to record again, this time with fellow Deltaresident bluesman and fiddler Henry “Son” Sims. He recorded several more times, and his last recording session took place in New York City in January 1934.

Ever the Delta performer, Charley sang and recorded songs that included people, places, and events in his community. “Tom Rushen Blues” bemoans the possibility of a friendly sheriff losing his office to one not so amenable to public drunkenness: “Laid down last night, hopin’ I would have my peace / I laid down last night, hopin’ I would have my peace / But when I woke up Tom Rushen was shakin’ me.” In “Green River Blues” he sings “I’m goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog,” the junction of the Southern (Yazoo) and the Dog (Mississippi Valley) railroad lines, which lay just a few miles south of Dockery Farms, and in “Pea Vine Blues” he sings about a lover leaving on a train that ran to and from Dockery: “I think I heard the Pea Vine when it blowed. / I think I heard the Pea Vine when it blowed. / It blow just like my rider gettin’ on board.” In “High Water Everywhere (Pts. 1 & 2)” Charley sings about the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, a flood that devastated much of the region: “Look-a here the water now, Lordy, / Levee broke, rose most everywhere / The water at Greenville and Leland, / Lord, it done rose everywhere / Boy, you can’t never stay here / I would go down to Rosedale, / but, they tell me there’s water there.”

Over his short yet illustrious recording career, Charley recorded a variety of songs, including blues, which he sang in a loud, rough voice (much of which was nearly incomprehensible), and religious songs such as “You Gonna Need Some body When You Die” (recorded under the pseudonym Elder J. J. Hadley), “Oh Death,” and “I Shall Not Be Moved.” His recordings earned him much widespread recognition, but his impact on American music stems primarily from those with whom he played, like Tommy Johnson, Son House, Big Joe Williams, Howlin’ Wolf, and Muddy Waters. Bukka White once said his ambition in life was “to be a great man—like Charley Patton.” Other blues musicians copied his style, and it can be reasonably argued that every rock and roller has been influenced by his style and music, whether consciously or not. His influence extends further than blues and rock and roll, though. Gospel patriarch Roebuck Staples, who also grew up on Dockery Farms, once said of Charley, “He was one of my great persons that inspired me to play guitar. He was a really great man.”

Known today as the “Father of Delta Blues,” Charley Patton died at 350 Heathman Street, in Indianola, Miss., on 28 April 1934, shortly after returning from his final recording session.

JAMES G. THOMAS JR.

University of Mississippi

Francis Davis, The History of the Blues (1995); David Evans, Big Road Blues: Tradition and Creativity in Folk Blues (1982), Blues World (August 1970); Gérard Herzhaft, Encyclopedia of the Blues (1997); Giles Oakley, The Devil’s Music (1977); Robert Palmer, Deep Blues (1981); Gayle Dean Wardlow, Blues Unlimited (February 1966); Gayle Dean Wardlow and Edward M. Komara, Chasin’ That Devil Music: Searching for the Blues (1998).

Pearl, Minnie

(1912–1996) COMIC FIGURE.

Minnie Pearl, the stage character created and performed by Sarah Colley, was one of the most popular and beloved performers in country music. Born on 25 October 1912 to a prominent family in Centerville, Tenn., Colley graduated from one of the South’s premier women’s schools, Nashville’s Ward-Belmont, and aspired afterward to a theatrical career. In 1934 she began work for the Sewell Production Company, which organized dramatic and musical shows in small towns across the South. Colley became director of the company, and while promoting a play in Sand Mountain, Ala., she met a woman who became the model for her later comic creation. The hill country woman told her wry stories that reflected a humorous outlook on life, which appealed to Colley, who was soon repeating the stories and emulating the woman’s temperament in creating the character of Minnie Pearl.

Minnie Pearl impressed audiences with her look. She wore a checked gingham dress, with cotton stockings, simple shoes, and most notably a straw hat with silk feathers and a dangling $1.98 price tag. “Howdeeee! I’m jest so proud to be here,” Pearl screamed as she came on stage, and audiences soon learned to deliver the friendly greeting “Howdeee” back at her. She told stories and gossip of the fictional Grinder’s Switch, which Colley based on the small-town doings of Centerville. Her routines revolved around her relatives and the towns people, such as Uncle Nabob, Brother, Aunt Ambrosia, Doc Payne, Lizzie Tinkum, and Hezzie—Minnie’s somewhat slow-witted yet marriage-evasive “feller.”

Minnie Pearl first appeared on the Grand Ole Opry in 1940 and would be a fixture on the show for 50 years. She was a regular on the television series Hee Haw from 1969 to 1991 and later appeared often on the cable television talk show, Nashville Now, with Ralph Emery. In 1975 she was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Colley, who married pilot and businessman Henry Cannon in 1947, was a far cry from the simple country girl of her alter ego. She was a gracious embodiment of Nashville’s gentrified society and active in numerous humanitarian causes. Diagnosed with breast cancer, she became a public spokes-woman in the 1990s for prevention and treatment of the disease, and the Sarah Cannon Cancer Center, the Sarah Cannon Research Institute, and the Minnie Pearl Cancer Foundation all honor her philanthropic work.

Colley died on 3 March 1996 after suffering a stroke, but the memory of her character, Minnie Pearl, survives as one of the South’s most memorable comic figures.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Minnie Pearl, Minnie Pearl: An Autobiography (1980).

Peer, Ralph

(1892–1960) MUSIC PUBLISHER AND TALENT SCOUT.

Although he was born in Kansas City, Mo. (on 22 May 1892), and although he never expressed a great fondness for southern folk music, Ralph Sylvester Peer became the single most important entrepreneur for country and blues recordings. He discovered, or was instrumental in the careers of, dozens of southern artists, both black and white, including Louis Armstrong, the Memphis Jug Band, Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, Mamie Smith, the Georgia Yellow Hammers, Fiddlin’ John Carson, Ernest Stoneman, Grayson and Whitter (with their initial recording of the murder ballad “Tom Dooley”), the Rev. J. M. Gates (one of the first black preachers to record extensively), the Rev. Andrew Jenkins (a prolific “event song” composer of items like “The Death of Floyd Collins”), and Gene Autry (who began as an imitator of Jimmie Rodgers). He initiated the practice of bringing recording crews into the South to document black and white folk music; he created the idea of having “blues” and “hillbilly” numerical series on commercial phonograph records; he was one of the first to publish and copyright country and blues songs; and in the 1930s and 1940s he became an innovative and trend-setting publisher of international reputation.

Peer’s father was a Columbia Record Company phonograph dealer in Independence, Mo., and by the time he was 20, Ralph Peer was working full time in the retail record business. By 1920 he was in New York working for the Okeh Record Company (actually the General Phonograph Corporation), then one of the smaller of the record companies and one looking for ways to get an edge on its bigger competitors. It found one, when on 10 August 1920 Peer recorded black Cincinnati vaudeville performer Mamie Smith singing “Crazy Blues,” a composition by a Georgia native named Perry Bradford. The record sold 7,500 copies within a week after its release and became the first in a long line of commercial recordings of blues by black artists. Three years later, in June 1923, Peer stumbled into a similar discovery for white folk music; on a field trip to Atlanta he recorded a millhand and radio personality named Fiddlin’ John Carson. Peer thought Carson’s singing was “pluperfect awful” but agreed to release his rendition of “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane,” an 1871 pop song by Will Hays. It duplicated the success of “Crazy Blues,” and soon Peer had initiated an “old-time music” record series on Okeh to parallel its blues series.

From 1923 to 1932 Peer made dozens of trips into southern cities—Dallas, El Paso, Nashville, Memphis, Atlanta, New Orleans, Charlotte, and Bristol—seeking out and recording on the spot hundreds of blues, gospel, jazz, country, Cajun, and Tex-Mex performers. On one such trip, to the Virginia-Tennessee border town of Bristol in August 1927, he discovered two acts that were to become cornerstones for commercial country music—the Carter Family and “blue yodeler” Jimmie Rodgers.

Central to all of this, though, was Peer’s unusual interest in both black and white music and his perception of ways in which the two could mutually influence each other. He theorized that both genres were just emerging from their vernacular regional base into the national limelight. He encouraged acts like the Allen Brothers, the Carolina Tar Heels, and Jimmie Rodgers to incorporate blues into their music and felt that this was one of the reasons that Rodgers enjoyed a wider national appeal than did the Carters.

In 1925 Peer left the Okeh Company and went to work for the Victor Company, trading his huge Okeh salary for more modest gains but an additional incentive: the right to control the copyrights on the new song materials recorded by his artists. Peer began to look for artists who could create original material, which he could copyright for them and place in his newly formed Southern Music Publishing Company (1928); such artists would get payment not only for records but for song performance rights as well. The increased emphasis on new material encouraged many blues and part-time country singers to become professionals and prompted the music as a whole to become more commercialized. And throughout the 1930s and 1940s he continued to build a publishing empire (which exists today as one of the country’s largest, the Peer-Southern organization) and to excel even at casual hobbies, such as horticulture, for which he received a gold medal for his important work. Though in later years he expressed disdain for the country and blues artists he developed (“I’ve tried so hard to forget them,” he told a reporter), and though some of his artists felt that he had exploited them, Peer laid the foundation for the commercialization of American vernacular music and thrust the rich southern folk music tradition into the mainstream of American popular music.

CHARLES K. WOLFE

Middle Tennessee State University

Nolan Porterfield, Journal of Country Music (December 1978); Charles K. Wolfe, in The Illustrated History of Country Music, ed. Patrick Carr (1979).

Penniman, Richard (Little Richard)

(b. 1933) ROCK-AND-ROLL SINGER.

Born into a large black family, in Macon, Ga., on 5 December 1933, Penniman adopted his nickname, Little Richard, at about age eight, when he began singing at church and school functions. By his early teens, Little Richard was performing on the road all across the South. He sang in minstrel shows, attracting audiences and selling snake oil. He sang the blues in bands following migrant workers as far afield as Lake Okeechobee in Florida, and he journeyed into cities to find gay clubs, where he played Princess Lavonne in the first of his several transvestite acts. Before he was 20 he had recorded, with little profit, for RCA twice and for Peacock Records once. These songs were conventional jump blues that made him sound like a melancholy Dinah Washington.

Success came in New Orleans in September 1955 when he joined Robert “Bumps” Blackwell on Specialty Records and made “Tutti Frutti,” one of the first and most important rock records. “Tutti Frutti” was a sublimated version of a bawdy song he had performed in sideshows for years but had never considered recordable. He and Blackwell then followed with a series of influential rock-and-roll hits. “Miss Ann” was about loving a white woman and included a 500-year-old rhyming folk riddle from the English oral tradition. “Long Tall Sally,” backed with “Slippin’ and Slidin’,” narrated the antics of standard black folk figures such as John and Aunt Mary, along with more contemporary ones like Sally, who was “built for speed.” “Keep a-Knockin’” and “Good Golly Miss Molly” emerged from the randy lore of prostitutes, circuses, and after-hours clubs and was reshaped as pop and teen lore—as when he purred to Molly, “When you rock ’n’ roll, can’t hear your mother call.”

By 1957, however, Little Richard was called away from rock and roll, entered Bible school, and began preaching. Since then he has made several attempts to return to the world of rock and roll that he helped create, and his performance as a rock-and-roll singer in the 1986 movie Down and Out in Beverly Hills brought good reviews and new attention. Nevertheless, he has not regained the power he had in the mid-1950s to mine the underground lore of the American South and fix it in an iconic style for the international youth culture.

When the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame opened in 1986, Little Richard was among the first inductees. His pioneering contribution to the genre has also been recognized by the Rockabilly Hall of Fame. In 2005 Little Richard starred in a popular commercial series and worked on a pop single with Michael Jackson benefiting victims of Hurricane Katrina. Although he has been called back to performing since the mid-1980s, Little Richard’s popularity has not matched that of his early career.

W. T. LHAMON JR.

Florida State University

W. T. Lhamon Jr., Studies in Popular Culture (1985); Charles White, The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock (1994); Langdon Winner, in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock ’n’ Roll, ed. Jim Miller (1976).

Pickett, Wilson

(1941–2006) SOUL ANDR&BSINGER.

The “Wicked” Wilson Pickett had one of the most fiery and distinctive voices of 1960s soul music. Many historians and fans agree that few artists could match Pickett’s deep, guttural intensity in the studio and onstage while he was in his prime during his years of recording for Atlantic Records. Born in rural Plattville, Ala., on 18 March 1941, Pickett was one of 11 children in a family of God-fearing sharecroppers. Here he got his first taste of music, singing in local Baptist church choirs as a child. But like many of his generation, Pickett tired of the hardships of the agrarian life and headed north in his late teens to find better opportunity.

Landing in Detroit, Pickett fell into singing with a local gospel group called the Violinaires, who in their brief career accompanied the likes of the Soul Stirrers and the Swan Silvertones at church gigs around the country. It was not long, though, before the pull of the secular music world of R&B became too strong for Pickett, and he joined an up-and-coming vocal group called the Falcons, which also featured Sir Mack Rice and Eddie Floyd. The union would prove successful as the Falcons found a Top 10 R&B hit in 1962 with the searing “I Found a Love,” featuring none other than Pickett on lead vocals.

Realizing his own solo potential, Pickett soon left the Falcons and was eventually signed by Atlantic Records in 1964. After a few initial misfires, Pickett struck gold when Atlantic sent him down to Memphis to record with its then-partner, Stax Records, where he began to hit his stride. He teamed up with Stax golden-boy producer, songwriter, and guitarist Steve Cropper, and the duo’s first effort, “In the Midnight Hour,” resulted in a definitive hit on the R&B and pop charts in 1965. The flurry of hits to follow in the next six years would prove to be the most successful era of Pickett’s career. Gritty work outs like “634-5789 (Soulsville, USA),” “Mustang Sally,” “Funky Broadway,” and “Land of 1,000 Dances” would set a benchmark in the Deep Soul movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Pickett did not confine himself to recording at Stax during these years. Several of his albums were recorded at the legendary FAME studios, another partner of Atlantic, in Muscle Shoals, Ala., with such prolific studio musicians, producers, and songwriters as Chips Moman, Spooner Oldham, and Rick Hall. Pickett even teamed up with young FAME studio musician Duane Allman on a blistering cover of the Beatles’ “Hey Jude” while in Muscle Shoals in 1969. Also during the late 1960s, Pickett collaborated on many popular songs with famed soul singer and songwriter Bobby Womack.

Pickett returned north in 1970 to record one of his last popular albums on Atlantic, Wilson Pickett in Philadelphia. Pickett’s commercial career soon started to wane, though, and after recording one more album for Atlantic in 1971 Pickett left the label. He would spend the 1970s at RCA struggling with mediocre material and new trends, such as disco, that did not always suit his gospel and soul past. During the 1980s Pickett all but dropped off the recording map, though he did occasionally perform.

After spending almost two decades battling drug addiction and having several run-ins with the law, Pickett reemerged in 1999 with the critically acclaimed It’s Harder Now on Bullseye Blues. The album gave him a comeback career on blues and soul circuits, earning him three W. C. Handy Awards and a Grammy nomination.

In 2004 Pickett retired from touring because of declining health, and two years later, on 19 January 2006, he died of a heart attack in his Reston, Va., home, leaving behind two daughters and a musical legacy matched by few of his era or any other.

MARK COLTRAIN

Hillsborough, North Carolina

Gerri Hirshey, Nowhere to Run: The Story of Soul Music (1984); Peter Shapiro, The Rough Guide to Soul and R&B(2006).

Powell, John

(1882–1963) MUSICIAN AND COMPOSER.

Powell was born in Richmond, Va., where his father, a schoolteacher, and his mother, an amateur musician, provided his primary musical education at home. He then studied music with his sister and piano and harmony with F. C. Hahr, a onetime student of Liszt. After receiving his B.A. from the University of Virginia in 1901, he studied piano with Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna (1902–7). There he also studied composition with Carl Navratil (1904–7). Powell made his debut as a pianist in Berlin in 1907. After four years of giving concerts in Europe, he returned to the United States, touring the country as a pianist and playing some of his own works. He continued to perform for many years in leading cities of Europe and America.

Powell composed many orchestral works, arrangements of folk songs, and choral settings; he also wrote three piano sonatas, one violin concerto, two piano concertos, and an opera, Judith and Holofernes. His other works include Rhapsodie Negre (piano and orchestra), 1918; Sonata Virginianesque (violin and piano), 1919; In Old Virginia (overture), 1921; At the Fair (suite for piano, also for orchestra), 1925; Natchez on the Hill (three country dances for orchestra), 1932; A Set of Three (orchestra), 1935; and Symphony in A Major (orchestra), 1947.

One of Powell’s most important achievements lies in the area of ethno-musicology. A methodical collector of the South’s rural songs, he was the founder of the Virginia State Choral Festival and the moving spirit behind the annual White Top Mountain Folk Music Festival. A member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, Powell was honored by his native state when Governor John S. Battle designated 5 November 1951 as John Powell Day. Powell died in Charlottesville, Va., in 1963.

For the most part southerners have contented themselves with inherited music, folk songs, and contemporary tunes. Apart from Powell, southern composers have remained virtually unknown except to other musicians. During the first half of the 20th century, however, Powell received national recognition and acclaim not only as a virtuoso performer of the classical repertoire at home and abroad but also as a composer of distinctively American music. Although Powell used African American elements in his Rhapsodie Negre and Sonata Virginianesque, his abiding concern was with the cultivation of Anglo-American folk music, of which there existed a rich heritage in the South. His Virginian antecedents and environment had given him a profound sense of intimacy with the founders of the American nation.

Powell felt strongly about the value of those Anglo-Saxon cultural and ethical forces that he believed had motivated the molders of the American past; he wished to preserve them for future generations and ensure the persistence of those Anglo-Saxon ideals that he regarded as characteristically American. By the early 1920s patient research and study had convinced Powell that American folk music derived from Anglo-Saxon sources was of fundamental importance to the cultural life of the United States and to the development of a truly national school of American music.

L. MOODY SIMMS JR.

Illinois State University

Daniel Gregory Mason, Music in My Time, and Other Reminiscences (1983); L. Moody Simms Jr., Journal of Popular Culture (Winter 1973).

Preservation Hall

Preservation Hall, a New Orleans institution, celebrates the emergence of jazz as a popular musical innovation in the South. Philadelphians Allan and Sandra Jaffe founded the hall in the early 1960s at the suggestion of (and on property owned by) artist Larry Borenstein. Endeavoring to revitalize the roots of jazz, it has supported a resurgence of interest and activity in classic New Orleans jazz.

At its outset, Preservation Hall provided a stage for fine old black jazz musicians who were unemployed. It also resuscitated a nearly extinct institution of musical life in the Crescent City—the community hall. Figures of the New Orleans revival, such as George Lewis, Jim Robinson, and Alvin Alcorn, took up musical residence there. Repeatedly throughout the past four decades, classic jazz musicians of the city have looked to Preservation Hall to renew the old idiom.

Like Perseverance Hall and San Jacinto Hall before it, Preservation Hall serves a total community. It addresses social and economic problems as well as cultural needs of the city’s jazz people. The preservationist impulse itself accounts for the fundamental contribution of Preservation Hall. In an effort to preserve jazz, the Jaffes and their associates have recycled it, establishing the classic jazz aesthetic for a new era. The hall has in fact reinvented and revitalized its community for the future by reaching decisively into the past.

Preservation Hall has succeeded by combining imported, updated marketing techniques with an abiding appreciation for local, traditional lifeways. Its success rests in large part upon the generous life support it has provided to old jazz greats. Preservation Hall emerged as part of a national folk revival in the 1950s and 1960s, and its activities have sought from the beginning to underscore the primal claim to jazz of black Americans.

Hurricane Katrina devastated the musical culture of New Orleans, including affecting Preservation Hall. The institution closed in August 2005 for several months after the building flooded. The first post-Katrina performance by the Preservation Hall Jazz Band was on 27–28 April 2006. Benjamin Jaffe, son of the owners, salvaged from the flood historic master tracks, which became the basis for Made in New Orleans: The Hurricane Sessions, a compilation of rare recordings, photographs, and text about Preservation Hall, which was released in July 2007.

CURTIS D. JERDE

W. R. Hogan Jazz Archive Tulane University

Jason Berry, Jonathan Foose, and Tad Jones, Up from the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music since World War II (1987); Al Rose and Edmond Souchon, New Orleans Jazz: A Family Album (1967; rev. ed., 1978).

Presley, Elvis

(1935–1977) ROCK-AND-ROLL SINGER.

Presley is probably the most famous southerner of the 20th century. Born in Tupelo, Miss., and reared in Memphis in near poverty, he became an international celebrity and one of the wealthiest entertainers in history. He has sold a billion record units worldwide, more than any other entertainer. Elvis had 149 singles on Billboard’s popular music charts, with 114 in the Top 40, 40 in the Top 10, and 18 singles reaching No. 1.

In 1954 Presley made his first recordings for Sam Phillips’s Memphis-based Sun Records in a style that drew from diverse sources—gospel (black and white), blues (rural and urban), and country. In effect, he and his band forged a dynamic new musical synthesis, which later became known as “rockabilly.” In 1955, after joining the Louisiana Hayride, a popular country show broadcast from Shreveport, Presley toured extensively throughout the South and acquired a vast and fervent following. National recognition came in 1956 with the success of his first RCA Victor release, “Heartbreak Hotel,” a series of network television appearances, and a movie, Love Me Tender. He was often the subject of controversy, for his frenetic performances and his conspicuous adoption of black-derived material and musical styles.

From 1956 to 1966, including his celebrated stint in the army (1958–60), Presley dominated popular music. He also starred in 31 feature films. After a brief decline in popularity during the mid-1960s, he began a sustained comeback in 1968 and 1969 with an acclaimed television special, and his television specials in 1973 and 1977 remain among the highest-rated musical specials. During this period Presley returned to live performances for the first time since 1961.

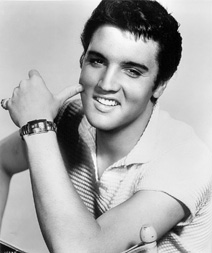

Elvis Presley, the “King of Rock and Roll,” age 22, 1957 (Graceland, Inc., Memphis)

In the 1970s Presley again became a major figure in American popular culture. He broke attendance records for his Las Vegas shows, and from 1969 to 1977 he performed 1,100 concerts across the nation. As the decade progressed, he often returned to the southern-rooted material and styles of his youth. Songs like “Amazing Grace” (1971), “Promised Land” (1973), and especially “American Trilogy” (1972) dramatized and reiterated Presley’s affinity for the South.

His death in 1977 and the subsequent outpouring of public interest in his life and music served to expose the many tensions and contradictions in southern culture, which he had so vividly symbolized. He was insolent yet courteous; narcissistic yet humble; pious (reflecting the Pentecostalism of his childhood) yet often hedonistic, especially in his final years; extremely wealthy yet ever conscious of his poor origins. His diet, accent, name, and, most of all, his music, remained indelibly southern. His Memphis home, Graceland (open to the public since 1982), one of the most popular tourist attractions in the South, is an enduring reminder of the quintessentially southern character of Elvis Presley. It attracts over 600,000 annual visitors, and in 2006 Graceland was designated a National Historic Landmark. In 1992 the U.S. Postal Service honored Presley with a postage stamp, which became the best-selling commemorative stamp in history.

STEPHEN R. TUCKER

Tulane University

Peter Guralnick, Careless Love: The Un making of Elvis Presley (2000), Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley (1994); Peter Guralnick and Ernst Jorgensen, Elvis Day by Day (1999); Valerie Harms, Tryin’ to Get to You: The Story of Elvis Presley (2000); Greil Marcus, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ’n’ Roll Music (rev. ed., 1982); Dave Marsh, Elvis (1982); Alanna Nash, The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley (2003); Stanley Oberst and Lori Torrance, Elvis in Texas: The Undiscovered King, 1954–1958 (2001); Jac Tharpe, ed., Elvis: Images and Fancies (1979).

Price, Leontyne

(b. 1927) GRAND OPERA AND CONCERT SINGER.

Leontyne Price was born in Laurel, Miss., where she grew up playing the piano and singing in the church choir. She graduated from Oak Park High School in 1944 and Wilberforce College in Ohio four years later. She then attended Juilliard School of Music on a scholarship, with financial aid from the Alexander F. Chisholm family of Laurel. Virgil Thomson selected her to sing the role of Saint Cecilia in a revival of his Four Saints in Three Acts on Broadway and at the 1952 International Arts Festival in Paris. After an audition with Ira Gershwin, she won the female lead in an important revival of Porgy and Bess opposite William Warfield, playing to packed houses from June 1952 until June 1954 on Broadway and in a world tour. In 1953 composer Samuel Barber asked her to sing the premiere of his Hermit Songs at the Library of Congress, and in 1954 she gave a Town Hall recital to enthusiastic reviews.

The NBC Opera Theater’s production of Tosca in January 1955 marked her professional debut in grand opera, although her first performance in a major opera house came two years later in San Francisco, as Madame Lidoine in Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites. In succeeding seasons she returned to San Francisco to interpret the title role of Verdi’s Aïda, Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni, Leonora in Il Trovatore, the lead in the American premiere of Carl Orff’s The Wise Maiden, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, Giorgetta in Il Tabarro, and the title role in Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos. With the Lyric Opera of Chicago she first sang Massenet’s Thaïs, one of her few failures, and the role of Liù in Puccini’s Turandot. She also appeared in Handel’s Julius Caesar and Monteverdi’s Coronation of Poppea in concert form with the American Opera Society.

Her Metropolitan Opera debut came on 27 January 1961, as Leonora in Verdi’s Il Trovatore. In October of that year she became the first black to open a Metropolitan Opera season, appearing as Minnie in Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West. She later sang Tatyana in Eugene Onegin, Pamina in The Magic Flute, and Fiordiligi in Così Fan Tutte at the Metropolitan. She opened the new house at Lincoln Center as Cleopatra in Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra. She has performed with the Vienna State Opera, the Royal Opera House in London, the Paris Opera, La Scala, the Verona Arena, the Berlin Opera, the Hamburg Opera, and Teatro Colon. In 1961 she sang recitals at the World’s Fair in Brussels and has given concerts throughout the world. She has recorded extensively, including American popular songs and black spirituals. She received 19 Grammy awards, more than any other classical singer, and was awarded a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989. She often returns to Laurel, Miss., and gave one of the first nonsegregated recitals there. She retired after a final performance on 3 January 1985.

Price performed recitals in the United States and Europe after her retirement, and she gave a memorable concert at Carnegie Hall in October 2001 honoring the victims of the September 11 terrorist attack. In 1997 she wrote a children’s book, Aida, which became the basis for a Broadway musical.

RONALD L. DAVIS

Southern Methodist University

Sir Rudolf Bing, 5000 Nights at the Opera (1972); Arthur J. Bloomfield, 50 Years of the San Francisco Opera (1972); Peter G. Davis, The American Opera Singer: The Lives and Achievements of America’s Great Singers in Opera and Concert from 1825 to the Present (1999); Hugh Lee Lyon, Leontyne Price: Highlights of a Prima Donna (1973); Helena Matheopoulos, Diva: Great Sopranos and Mezzos Discuss Their Art (1992).

Price, Ray

(b. 1926) COUNTRY MUSIC SINGER.

Ray Price, in a music career that has lasted more than 55 years, helped country music survive the death of Hank Williams and the introduction of rock and roll by creating a more forceful, rhythm-driven form of honky-tonk music. Later, in the 1960s, he broadened country music’s audience by moving toward a lush, sophisticated sound.

He was born Noble Ray Price on 12 January 1926 in the east Texas farming community of Peach in rural Wood County. His parents split up when he was a young boy. He grew up spending summers working on his father’s farm in Perryville, Tex., and attending school in Dallas while living with his mother. He also took classical voice lessons for several years, encouraged by his step-father, an Italian immigrant who loved opera. The vocal control and power he learned would later set him apart as a singer who could soar above his arrangements with a clarity and power that many other country singers lacked.

After serving as a U.S. Marine in World War II, Price began singing in Dallas-area nightclubs and, before long, on the city’s Big D Jamboree radio show. He recorded his first songs for Bullet Records in 1951 and the following year signed with Columbia Records. Moving to Nashville, he briefly roomed with Hank Williams.

Price had several Top 10 hits early in his career, including “I’ll Be There (If You Ever Want Me)” and “Release Me,” but it wasn’t until 1956 that he scored a No. 1 hit, with “Crazy Arms.” The latter established Price’s signature sound, a 4/4 shuffle beat spiced by single-note fiddle and a stinging steel guitar. Other country dance floor hits followed, including “I’ve Got a New Heartache,” “My Shoes Keep Walking Back to You,” “City Lights,” “Invitation to the Blues,” and “Heartaches by the Number.”

In the 1960s Price shifted from traditional country music to a smoother style featuring sweet violins rather than raw fiddles. Although songs like “Make the World Go Away,” “The Other Woman,” and his emotion-drenched version of “Danny Boy” all did well, it was not until 1970, when he recorded a Kris Kristofferson song, “For the Good Times,” that he returned to the No. 1 spot.

Price also has been known for identifying significant songwriters early in their careers. He cut the first major hits of Kristofferson, Bill Anderson, and Roger Miller, and he recorded early hits by writers Harlan Howard, Willie Nelson, Hank Cochran, Danny Dill, and Mel Tillis. He also was known for hiring top musicians for his Cherokee Cowboys band, including steel guitarists Jimmy Day and Buddy Emmons, fiddlers Tommy Jackson and Buddy Spicher, and guitarist Pete Wade. Future country stars Willie Nelson, Roger Miller, Johnny Paycheck, and Johnny Bush were all members of his band before going on to launch their own singing careers.

Price has continued to perform into his eighties, his voice still rich and resonant. In March 2007, he released an album, Last of the Breed, with old friends Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard, both of whom consider Price a primary influence and, as Nelson put it, “the best country singer I’ve ever heard.”

MICHAEL MCCALL

Country Music Hall of Fame

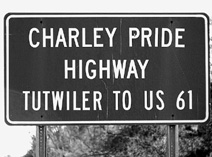

Pride, Charley

(b. 1938) COUNTRY MUSIC SINGER.

A little over a decade after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball, Charley Pride accomplished a similar feat in country music. Born in Sledge, Miss., in the depths of the Great Depression to a family of poor cotton laborers, Pride not only opened new avenues of acceptance to minorities but set high standards of excellence in the field of country music.

Many blacks in the Mississippi Delta were drawn to the blues, but Pride was more interested in country music, especially the songs of Hank Williams. At night he would listen to country music radio programs, memorizing the words of their songs. The only member of his family with any musical inclination, Pride scraped up enough money when he was 14 to buy his first guitar, which he learned to play by listening to different picking styles. (Pride received only $3 per 100 pounds of cotton he picked with his 10 brothers and sisters.) When Pride left Mississippi three years later, he departed not to pursue a career in music but to try for athletic success through baseball.

Pride’s luck with baseball was short lived. After stints with the Memphis Red Sox and Birmingham Black Barons, teams in the Negro American League, and two years in the army in the late 1950s, Pride eventually made it to the minor leagues, playing in 1960 for a team in Helena, Mont. Pride often sang between innings; the response he received from the venture encouraged him to sing more. Through his landlady in Helena he got his first musical break, singing in a local country bar. Still hungry to play major league baseball, Pride earned a tryout in 1961 from the California Angels. He did not make the team, and he returned to Helena, where he worked for a refining plant and sang in area nightclubs. The nightclub performances led to an invitation from Red Sovine in 1963 to do a recording audition in Nashville. Pride auditioned in Nashville for Chet Atkins the following year and signed with RCA Victor after the session.