BEFORE WORKING WITH SPECIFIC PAIN CONDITIONS, it is essential to review all your medical assessments and previous treatment experiences. It is good to know the history of your pain condition, any diagnoses you have received, and also how you understand these labels. In addition, it is important to know what treatments you have experienced and how successful these have been, as well as what types of professionals you have worked with. We suggest that you review this information for yourself and write it down—that way your current doctor has all of your information on hand so that she or he can best help you. This is the beginning of forming a working alliance that will maximize positive results.

We must always be open to the possibility that there can be structural or organic causes of pain. It’s essential to explore such “hard wiring” sources even though there may also be evidence of psychological components such as abuse or loss. It is always necessary to consider both physical factors and psychological/emotional/traumatic factors when deciding how to begin dealing with specific pain syndromes.

Ask yourself how much of the pain that you are experiencing now is related to your medical diagnosis? If the answer is, “I think it’s 100 percent related to what the doctor told me,” then you should focus more closely on reviewing our tips and guidance about getting the medical help you need. But if the answer is, “I feel like I’ve done a lot of healing. And yet, I think I still have a lot of stress that comes from the accident (or whatever event generated the pain in the first place),” then most certainly begin to look for possible emotional and traumatic sources. Likewise, if there seem to be earlier traumatic experiences that have not been resolved, this too might indicate a contributing factor to ongoing psychological stress/pain and prompt you to investigate further.

We begin by focusing on one of these two sides, either structural or “psychological,” to keep things simple. But we never neglect the other. So for example, even though there might be physical injury, this does not eliminate the need to work on the traumatic and emotional aspects. We also encourage you, when working on these emotional aspects of your pain, not to eliminate the possibility that there might also be a mechanical issue at hand, such as something being torn, ruptured, or broken. But at the same time, you don’t want to search endlessly for an organic cause when it simply might not exist. Also, it’s important to consider the fact that for some people, getting a specific pain diagnosis can be more stressful than enlightening, especially if the pain is related to a life-threatening condition like cancer.

When working with any specific pain condition, we consider five levels of trauma. You will notice our references to these trauma dimensions throughout this chapter and elsewhere in this program.

1. Trauma that is directly linked causally to the pain.

Some key examples are in the aftermath of illnesses, accidents, injuries, and surgeries.

2. Single event trauma that precedes the pain.

This can include falls and other accidents (as in #1), but more broadly involves events like rape, robbery, mugging, and natural disasters.

3. Developmental trauma.

This includes prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal distress, as well as issues with early parental bonding and ongoing parental relationships. This “attachment trauma” is different from single event trauma because it is generally pervasive and unconscious. Sometimes, if the child or mother is ill, bonding is interfered with. This can be particularly problematic if the mother suffers from postpartum depression. This kind of early trauma can lay a foundation for later pain conditions. If your parents are still alive, they might possibly provide some information. Of course this can be tricky, though sometimes a frank discussion can, in itself, be healing.

4. Childhood abuse.

Molestation, neglect, loss, and other kinds of repetitive emotional and psychological trauma frequently result in dissociation and can be the most corrosive roots of pain because they are often caused by the individuals who are supposed to love and protect us. These kinds of confusing situations make it very difficult to feel anger and so we often turn it on ourselves. Both abuse and developmental arrests can slow down the recovery from pain. If you suffer from the effects of these issues, patience and persistence are important comrades on your journey.

5. Trauma caused by chronic pain conditions.

Any chronic pain condition that has persisted can become traumatizing in and of itself. Pain causes fear and contributes to the emotional pain of depression. Each person’s specific pain condition has unique undermining effects on mind, body, heart, spirit, and on daily life functioning.

Even if you do not suffer from the particular pain conditions described in this chapter, you can still benefit from reading about each condition and the methods used to cope with and possibly transform it. We have organized this material as a general progression from relatively simple to deeper and more complex pain syndromes. Therefore, we will start with the more common neck and back pain problems.

When this kind of pain is in the acute phase, it is easily treated by rest, cold, and anti-inflammatory medications and often goes away on its own. However, when this type of condition becomes chronic, the situation becomes more elusive because the causes may not be easy to trace to a precipitating event. Diagnosis can be a lengthy process and this may mean that it takes the patient longer to find relief. The assessment might include MRIs, CT scans, and X-rays, various painful injections including epidurals, nerve root blocks, joint injections, and other types of nerve function evaluations. Of course, it is best if diagnosis can be done with non-invasive, non-painful procedures. This is something to consider with your physician or medical team.

Possible causes of back pain can include simple “muscle strains,” structural issues like disc problems that include sciatica, joint pain, and stenosis (narrowing of the spinal channel due to arthritis); and structural irregularities including scoliosis and osteoporosis. Still other sources of serious pain can include tumors, infections, and neurological problems.

The shoulders are one of the most common regions of pain problems and are particularly distressing because they are the most movable joints in the body and are used repeatedly for so many necessary movements. Causes of shoulder pain can include rotator cuff problems, tears and tendonitis, ligaments that tighten and cause “frozen” shoulder, and injuries that can fracture or separate the shoulder.

Vince’s symptoms had begun a few months before our appointment. He was working in his garage and picked up a starter motor to put into his car. As he lifted it, he felt “a twinge of something in his arm.” The next day his shoulder felt tight and sore. Over time, the pain became more acute and his range of motion progressively worsened, becoming chronic.

Vince’s story is surprisingly common: when the amount of pain isn’t congruent with the circumstances of a minor accident, we then begin to explore a possible trauma-related reason behind it.

Not surprisingly, Vince attributed his shoulder “strain” to working on his car. This is somewhat like the person who reaches down and picks up a piece of paper, only to have their back go into spasm. Common sense, and the clinical observation of most chiropractors, physical therapists, and massage therapists, dictates that this was already “back primed”—an accident waiting to happen. In Vince’s case, since there was no apparent physical injury, his physical therapist referred him to me in the hope of avoiding more difficult procedures.

Vince was obviously confused about seeing a “mind doctor,” and was reluctant to engage with me. Sensing this, I reassured him that I would not be asking him personal questions, but would just focus on helping him get rid of his symptoms. “Yeah,” he said, “my body sure is broke.” I asked him to show me how far he could move his arm before it started to hurt. He moved it a few inches and then looked up at me: “That’s about it.” “OK, now I want you to move it the same way, but much slower, like this.” I showed him with my arm. “Huh,” he replied as he glanced at his arm. He was clearly surprised that he could move it a few inches further without the pain. “Even slower, this time, Vince. Let’s see what happens this time . . . I want you to really give it your full attention; focus your mind on your arm now.” Moving slowly allowed him a greater awareness of his arm. Just moving it quickly, without mindfulness, would have been likely to recreate the protective holding pattern, causing more pain.

His hand began to tremble and Vince looked to me for reassurance. “Yes, Vince, just let that happen . . . it’s a good thing . . . it’s your muscles starting to let go. Try to keep your mind focused there, with your arm and with the trembling . . . just let your arm move the way it wants to.” The trembling went on for a while and then stopped; his forehead broke out in sweat.

As he moved to the edge of the bracing pattern, some of the energy held in his muscular-defense pattern began to release. This included the involuntary, autonomic nervous system reactions, such as shaking, trembling, sweating, and temperature changes. Because these are sub-cortical actions, the person does not have a feeling of control over his or her reactions. This may be quite unsettling at first. My function here was that of a coach/midwife, helping him to befriend these alien sensations, especially since he was wholly unaccustomed to involuntary reactions that he couldn’t control.

“What is this, why is it happening?” he asked me in the voice of a frightened child. “Vince, I’m going to ask you to just close your eyes for a minute now and go inside your body . . . I’ll be right here.” After some moments of silence, his hands and arm began to extend outward: his whole arm, shoulders, and hands were now shaking more intensely. “It’s OK for that to happen,” I encouraged him, “Just let it do what it needs to do and keep feeling your body.”

“It feels cold then hot,” he said as he continued to reach out, moving now to about 45 degrees. Then he halted abruptly. His eyes opened wide, amazed that he could reach out so far without pain. At the same time, he seemed agitated; his face suddenly turned pale. He complained of feeling sick.

Instead of backing off, I coached him to stay present with his physical sensations. He started to breathe rapidly. “Oh my God, I know what this is.” “Yes, good,” I interrupted, “but let’s just stay with the sensations for a little longer, then we’ll talk about it, if you want. Is that OK?” Vince nodded and moved his arm back and forth from his shoulder as though he were sawing a piece of wood in slow motion. The trembling increased and decreased again, then settled. Tears flowed freely from his eyes. He took a deep spontaneous breath and then reached out, fully, in front of himself. “It doesn’t hurt at all!” This corresponds with what we often have found with chronic pain: there is generally an underlying bracing pattern, and when the bracing pattern resolves, the pain often dissolves.

A large percentage of chronic neck, shoulder, and back pain is related to accident and injury. Our musculoskeletal system is designed to protect our bodies from threat of harm by bracing. Pain problems occur when these bracing patterns are never released. For Vince, it was the slow mindful movements that let him resolve his bracing pattern. Although Vince’s body had already developed this bracing pattern, it took the minor strain from lifting the starter motor into his car to catalyze the reaction that set off the pain.

At the end of his session, Vince opened his eyes and looked at me. Because of the connections made between his mind awareness and his body sensations, he was now able to form new meanings. He told me about the following event. About eight months earlier, he had gone shopping for his wife. As he came out of the grocery store, he heard a loud crash. Across the street, a car had smashed into a light pole. He dropped his shopping bag and ran to the accident. The driver, a woman, sat motionless in an apparent state of shock. The motor of the car was still running so he reached across her inert body to turn off the key, which is standard procedure to prevent fires or explosion. Just as he started to turn the key, he saw a young child in the passenger seat, his head fatally injured by an air bag. And then Vince told me why his shoulder got frozen: “I was fine before I saw the kid. As a fireman, I’m used to doing things like that, things that are dangerous . . . but when I saw the kid, part of me wanted to grab my arm back and turn away . . . I felt like puking . . . and the other part just stayed there and did what I had to do . . . sometimes it’s really hard to do what you have to do.” I agreed. “Yes, it’s hard and you and your buddies keep doing it anyway. Thank you.”

“Hmm,” he added as he was leaving, “I guess I have to learn to mind my body.” Vince had learned that mind and body are not separate entities; that he was a whole person. He said he wanted to learn more about himself and came in for three more sessions. He learned how to better handle stressful and conflicting situations and, needless to say, didn’t need surgery.

While it was Vince’s shoulder that was frozen, any part of our bodies can become frozen. By gently teasing out the conflicting forces and letting each one have its unobstructed voice, we too can thaw our frozen parts (one to reach out—and the other to retract in horror, in Vince’s case). In the slow mindful movement of sawing his hand back and forth, Vince began to explore the inner movement “held in check” and locked into a bracing pattern. He had now separated two conflicting impulses: one involving reaching toward the keys and the other of pulling away in revulsion.

Another example is Bill, the patient with shoulder pain in chapter 1 who was able to resolve his pain by being supported gently, and gradually releasing his arm and its attachments through the mid-back area. With help, he first tracked the bracing patterns to his fall into the water during the weekend celebration of his engagement as a young man, and later realized that these patterns overlapped with his headlong bicyclecrash into the utilities truck. As his arm and shoulder were cradled, Bill experienced gentle waves of trembling and shaking, which allowed the constriction to release. Over the span of several sessions, the neuromuscular pain, which had been locked in his body for more than six years, was released and resolved.

Now, while these cases are quite dramatic, you can certainly learn to work with various types of shoulder, neck, and back pain using the exercises in this book, including the following exercise.

If you have problems in these (or other) areas of your body, take a few minutes to try a simple experiment, applying some of the principles that worked for Vince and Bill.

Sense the location that feels locked or constricted. Explore the sensations in the area surrounding the locked place. Name these for yourself using the language of sensation: tight, constricted, cold, hot, tingly, vibrating, shaking, trembling, and so forth.

Begin to shift your breathing so you can begin to explore the locked area. Imagine that you can breathe into the center of the locked area. Notice what begins to happen. Is there expansion? How do you know?

Sense any movement your body might want to make. Imagine the movement before you allow it to begin. Like Bill, does your arm want to be supported and cradled with pillows or a soft blanket so that it can gently vibrate or tremble to release the shock of a current or past injury? Like Vince, does your arm want to reach out in front of you to make rhythmic motions?

Slowly, and with gently directed awareness, allow these movements to begin. As you sense the motions, allow them to continue more slowly still. You might inhale as you allow part of a movement, and as you exhale, pause and feel your body’s response. Continue until you reach a sense of completion, at least for now.

If you’d like, spend a few minutes recording your experience in your pain journal. Over time, notice the differences that take place in the previously locked area and in the rest of your body.

Fibromyalgia is a condition that affects millions of Americans, the majority of whom are women. These individuals suffer from an array of symptoms, primarily persistent muscular pain. Many of these people also suffer from chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and spastic colon. Still other individuals may be afflicted with migraines, severe premenstrual syndrome, and even heart arrhythmias.

At one time, the medical model attributed fibromyalgia to “psychosomatic” origins—in other words, that it was “all in your head.” These sorts of labels were counterproductive and did little more than “blame the victim.” They dismissed patients, who had very real symptoms, as hypochondriacs and malingerers, implying that they were basically imagining their complaints.

Now that the tide is finally turning, many researchers are looking for viral, biochemical, and genetic causation to fibromyalgia. Yet, as is often the case when the pendulum swings, the truth has been passed over in the race for the new breakthrough. While we can’t rule out molecular and genetic influences, the current opposing psychosomatic-versus-biological explanations have largely missed the mark and are of limited value in suggesting effective treatment.

From the perspective of this program, one of the most important underlying factors in fibromyalgia is the stuck fight/flight/freeze (i.e. trauma) reaction. Simply put, the unreleased muscle tensing leads to pain, which leads, in turn, to fear and more bracing, and more pain, and so on. When enough of this pain affects enough of the body, people are diagnosed (somewhat arbitrarily) with “fibromyalgia.”

Neglect and abuse are powerful factors in predisposing the development of fibromyalgia. Another important component of fibromyalgia is repressed anger. In general, traumatized individuals are afraid to feel their anger and own their healthy aggression.

In seeking resolution to the pain, you must proceed ever-so-slowly and carefully because of the severity of symptoms, particularly if they involve the gastrointestinal system, migraines, or severe PMS. At the same time it is essential that you consult an internist, as some of these symptoms might conceivably be due to an organic cause. Keep in mind that as you begin to release some of this locked-in energy, there may be a temporary exacerbation of your symptoms. Less is more, so proceed at your own self-compassionate pace. At any time, if you feel that working with your symptoms may be too much, please seek a therapist, particularly one trained in Somatic Experiencing or another modality that works effectively in a very gentle way. Trust your instincts and intuition to find the right therapist for you; no matter how many diplomas they may have hanging on their wall, rely on your feelings about who is right for you.

Helen had begun to show the early signs of fibromyalgia. While this was causing her concern, this was not the reason she sought consultation. She came to the office because of emotions that she could not “understand.” Her friends had become concerned that she was increasingly submissive and unpredictably explosive. At the point when her behavior threatened her relations with friends and colleagues, she too became concerned. Helen did not make the connection between her physical and behavioral changes and an event that had transpired three years earlier, which, as far as she was concerned, was irrelevant.

I asked Helen to recall a recent encounter with a colleague that illustrated her sudden shift in behavior. We both noted Helen’s bodily reactions as she recounted the event. I noticed that her shoulders were high and “hunched over” and brought that to Helen’s attention. She reported that her shoulder and neck were getting tight and painful. “It’s like the pain I feel when I am under stress.” Helen then said that she felt that she had done something wrong. I asked if this was a feeling or a thought. After a moment Helen replied: “I think it’s a thought.” We both giggled. Very often we are not aware that we are having a thought. Frequently we confuse our thoughts with reality, rather than realizing they’re just thoughts. I then asked her to bring her attention to her body. She reported a sinking sensation in her belly. “It makes me hate myself.” Helen was taken aback by this sudden outburst of self-loathing.

Rather than analyzing why she felt that way, I guided her back to the sensations in her body. After a pause, Helen reported that her “heart and mind were racing a million miles an hour.” She then became disturbed by what she described as a “sweaty, smelly, hot sensation” on her back, which left her feeling nauseated. The pain in her neck and shoulders intensified to a 7.5 on a pain scale of 10. The pain, she said, “is driving me crazy.” Helen now seemed more agitated—her face turned pale and she felt an urge to get up and leave the room. After reassurance, Helen continued tracking her discomfort. The pain intensified again, and then gradually diminished. Following this ebb and flow, Helen became aware of another sensation—a more specific tension in the back of her right arm and shoulder.

When she focused her attention on this sensation, she started to feel an urge to thrust her elbow backward. I offered a hand as a support and as a resistance so that Helen could safely feel the power in her arm as she gently pushed it slowly backward. After pushing for several seconds, her body began to shake and tremble. Her legs also began to move slowly up and down as if they were on a sewing machine treadle, or as though she were running.

As Helen’s arm continued to slowly press backwards, the shaking decreased and she felt as though her legs were getting stronger. “They feel like they want to move,” she said. Helen then reported noticing a strong urge propelling her forward. Suddenly, a picture flashed before her: a street lamp and the image of a couple who had helped her. “I got away . . . I got away . . . ” she cried softly. It was then she remembered molding into the man’s torso as he held a knife to her throat. She went on, “I did that to make him think I was his . . . then my body knew what to do and it did it . . . that’s what let me escape.”

The story that her body had been telling then emerged in words: three years earlier, Helen had been the victim of an attempted rape. While she was walking home after visiting a friend in an unfamiliar neighborhood, a stranger had pulled her into an alley and threatened to kill her if she didn’t cooperate. Somehow, she was able to break free and run to a lighted street corner where two passersby yelled for the police. Helen was politely interviewed by the police and then taken home by her friend. Surprisingly, she could not remember how she had escaped, but was tearfully grateful to have been left unharmed. Afterward, her life appeared to return to normal, but when she felt stressed or in conflict, her body was still responding as it had when the knife was held to her throat. Her body was bearing the burden in the form of chronic pain.

Helen found herself helpless and passive or easily enraged under everyday stress, not “realizing” that this was a replay of the brief pretense at submissiveness that had probably saved her life. Her “submission” successfully fooled the assailant, allowing a momentary opportunity for the instinctual energy of a wild animal to take over, propelling her arms and legs in a successful escape. However, it had all happened so fast that she had not had the chance to integrate the experience. At a primitive body level, she still didn’t “know” that she had escaped, and remained identified with the submissiveness rather than with her complete two-phase strategy that had in fact saved her life. Somatically and emotionally, it was as if part of her was still in the assailant’s clutches.

After processing and completing the rape-related actions, Helen now reported having an overall sense of “capability” and empowerment. In place of the previous submissive self-hatred, she was “back to even more of her (old) self.” This new self came from being able to physically feel the motor response of elbowing her assailant, and then sense the immense power in her legs, which had carried her to safety. Helen realized that the painful tension in her neck, shoulders, and legs was the energy needed to protect herself, energy that got stuck. In her words, “It released like waves of warm tingly vibration.” She had made a major step in freeing herself from the prison of chronic pain. In the following weeks her symptoms lessened, and though she had some flare-ups, her symptoms gradually disappeared. Helen’s fibromyalgia was mild, and her early childhood history of trauma was relatively minor; it should be noted that in most cases of fibromyalgia changes occur more slowly over time.

How many of our habitual behaviors and feelings are outside of our conscious awareness or are long accepted as part of ourselves, of who we are, when in fact they are not? Often, these behaviors are reactions to events long forgotten or rationalized by our minds, but remembered accurately by our bodies. Sigmund Freud once said: “The mind has forgotten but the body has not, thankfully.” We can thank Freud for correctly surmising that both the imprints of horrible experiences as well as their antidotes—in the form of resiliency and the capacity for forming new experiences that lead to transformation—exist within our living, feeling, knowing bodies.

Results with Helen were achieved when she could safely feel and release her anger and re-own her sense of self-protection. Here are some ways you can try this approach for yourself.

Sit comfortably and slowly push your legs into the ground. To do so, you might want to place both feet on the floor, making sure that the rest of your body is supported—whether you are lying or sitting.

As you breathe in, feel your energy rise through your core, and as you breathe out, press down gently through your feet (see the grounding exercise, track 4). Experiment for a few breath cycles; if this is not helping you feel more grounded, reverse the directions (pressing down through your feet and legs as you breathe in and letting go as you breathe out). Notice what you begin to feel.

Sense any anger you might be aware of related to fibromyalgia or another pain condition. Imagine the movements your body might want to make to express this frustration, anger, or irritability. For example, you might perceive pushing or chopping motions, or sense an impulse to move your arm to strike out.

Allow this movement to occur very, very slowly so that you can integrate all the subtleties that take place. As examples, allow your hands to push forward very slowly, feeling each movement; or allow your hands to make slow motions, gentle karate chops into a pillow. You can also add resistance by placing a soft, thick pillow against the wall (or better still, asking a friend to hold the pillow) as you gradually push into it.

It is important to move gradually to complete the action of healthy aggression, and thereby release the stuck survival energy that is locked in your muscles and nervous system. The key is to feel yourself completing the full range of the movement and directing the movement. It isn’t enough to mindlessly or mechanically karate chop a pillow. You must feel what it is like to prepare for the strike, align your spine with the strike, and come down with the intention of cutting through that obstacle—and then feel your hand successfully shear through the pillow.

Give yourself time to stop and integrate what you have experienced. How does your body feel different? When you think about the stimulus for your anger, how is your reaction different now? You may want to record what you are noticing in your pain journal so that you can come back to this when you feel anger activation again.

Migraine headaches arise from a fundamental dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system. What’s known about migraines is that they seem to be caused first by a constricting of the blood vessels in the head, followed by a precipitous dilation, or expansion, of these blood vessels. It is this abrupt stretching that causes the pain.

To reduce the severity of migraines, it’s important to focus on what happens before the migraine, especially the preliminary signals that occur just before you recognize its onset. This is sometimes called the prodromal stage of migraine. Often, people with migraines will identify flickering lights, an aura, a certain feeling or sensation, a taste or even a smell prior to the onset of the full migraine. When they learn how to become aware of what happens just before the first symptom appears, they generally find that the attack doesn’t occur or at least is diminished We have found that the majority of individuals who practice mindful awareness and tracking of sensations have gotten significant relief with the frequency and severity of their migraine symptoms. This type of work must be conducted at a careful pace, because symptoms like migraines have a great deal of locked-in energy that requires gradual release.

Donna had struggled with migraines off and on during the last ten years. Her only child, Sam, had recently graduated from college and was out on his own. She and her husband were now empty nesters who had frequent surges of tension as old conflicts resurfaced in more intense forms without the buffering that their son Sam had provided.

In the last two years, Donna’s migraines had worsened as she moved into perimenopause. She had tried several medications without significant results, and acupuncture brought only temporary relief. At the time she sought treatment, she was missing an average of half a day a week at work because of the unmanageable pain. She was becoming concerned about losing her job, a worry that increased her complaints of anxiety as well as the frequency of migraines.

Donna’s history revealed several traumatic events related to men, beginning with her father, who had had numerous affairs and a gambling addiction. This situation had thrown the family into bankruptcy. She also reported an attempted date rape in high school by her boyfriend of two years, and feelings of betrayal because of her husband’s flirtations early in their marriage. A trial of couple counseling at that time had had little long-term benefit.

Although Donna was motivated and quite eager to relieve her headaches, it was very difficult for her to connect with her body sensations. In fact, her body was the enemy, the source of pain that was also holding on to excess weight (related to medications and hormonal fluctuations). “I don’t want to get to know my body,” she said. “I understand from what you’ve told me that I cannot recover from migraines without being able to feel what’s happening so I can prevent the full attacks, but all I feel is disgust.” After learning about mindfulness, however, Donna was more hopeful. “I’ve heard about this approach and I’d like to try it.”

Her first attempts at practicing mindfulness were often interrupted by self-judgment and obsessive negative thinking. She participated in several mindfulness sessions, using tools similar to the exercise that follows. Eventually, Donna was able to lower her pain a point or two when she chose to lie down and practice steady, balanced breathing. This success helped her to track sensations that seemed to underlie the pain. She was ultimately able to utilize her obsessive-thinking style as a skill to help her name and write down each sensation that occurred. This self-designed practice allowed her to connect enough with her body to move through each migraine episode—each time with a little more ease.

Gradually, she was able to identify the earliest signs of a migraine, which for her were throbbing sensations in her temples followed by feelings of pressure in the front of her head. She used these warning signals as opportunities to lower her stress at work or at home, including requesting that her husband prepare meals so she could rest.

Donna’s approach suggests a strategy you might try. Like Donna, when you notice sensations that herald the beginning of a pain episode, you can remind yourself that these are frequently signs that a migraine or other pain symptom might be approaching. At that point, if at home, you can train yourself to ask family members to prepare meals or complete other chores, so you can lie down for an hour or so to use the tools you know to lessen the pain. If the symptoms occur at work, you can practice shifting to less demanding tasks or ask a team member for help.

Gradually, using these strategies, Donna’s headaches diminished in intensity and frequency. “I still have migraines,” she reported at our last session, “but I know I can rest and I know that I can bring the pain down. What I have now that I did not have before is peace of mind.”

Mindfulness-based practice can be useful with any kind of pain. If you’d like to explore this, find a comfortable position where your body feels supported and where you are relatively free from distraction.

Begin by using one of the tools you have learned thus far from the Freedom from Pain program that helps you connect safely and comfortably with your body. For example, go back to the Just One Breath exercise (track 5) and/or work with the Securing a Resting Place in Your Body exercise (track 3).

Then, when you’re ready to begin exploring this exercise, imagine that you can step into a new moment with beginner’s mind as if for the very first time. Begin to notice what you find in this new moment.

Take an inventory of your thoughts, feelings, sensations, inner images, movements in your body, posture, and gestures. Describe them out loud. For example: “Now I feel that pressure in my temples and notice that my vision is beginning to change like it does before a migraine.” Or with another type of pain: “Right now, I can feel a burning in my left leg, a cramping in my stomach, and I have the thought that I’m discouraged. I don’t think I can get past this pain.”

When you reach a natural pause in the flow of your awareness, take a deep breath in and hold it; then allow yourself to accept, with kindness and compassion, that you feel a pressure in your temples and a blurring and narrowing of your vision (or burning in your left leg, a cramping in your stomach, or the thought that you’re discouraged because you don’t think you can make it through this). Accept the thought, and accept the pain. Hold all of the awarenesses that you have named along with your breath . . . and when you’re ready . . . let them all go as you breathe out.

Then with the next breath in, step into the next new moment as if for the very first time. Explore this new moment and name for yourself what you’re aware of at that point; for example: “I’m still feeling the pressure in my temples and the changes in my vision, except the pressure is lighter and there is now a pulsing in the back of my head.” Another possibility might be, “I’m still feeling the burning in my left leg, only it’s moved down into my lower leg,” and so on.

When you sense a pause or completion, take a deep breath in and hold it while you accept with kindness and gentleness toward yourself whatever you’re experiencing. Vocalize what you are sensing and feeling. For example, maybe the pressure has lightened and the pulsing is slowing. Or the burning in your left leg has moved lower, you still have the stomach cramping, and you’re wondering, “Can I really make it through all of this? Will I have a normal life again?” Hold your breath along with all of these thoughts and feelings and when you’re ready, let it all go along with your breath as you exhale.

Continue this process of accepting what you are experiencing, naming what you are aware of, then holding your breath and releasing all of your experience through your out-breath; then return to your body with the next new inhalation as if it were the very first time.

You can continue to explore mindfully additional, new moments in this way until you reach a sense of completion or readiness to stop the exercise. Generally, less is more—so no need to push yourself. Also, check in and review your progress as you continue this exercise over time. What has happened during the time you’ve been practicing this mindfulness exercise regularly? What is different about your sense of pain? Do you experience more energy, or feel an enhanced sense of aliveness? Are you noticing more fluid shifts between constriction and expansion in your body? We encourage you to record your experiences with this exercise in your pain journal.

There are many types of mindfulness exercises that can help you strengthen your awareness of sensation in your body. Coupling nonjudgmental thoughts with sensate awareness (body awareness), and using your breath to open pathways in your body, can help you shift your discomfort into a dynamic flow of self-discovery.

Interstitial cystitis, sometimes called bladder pain syndrome, is a disorder characterized by pain associated with urination or with increased urinary frequency (often as frequently as every ten minutes). There is also urgency and/or pressure in the bladder and even in much of the pelvis. It is more common in women than men. With men, mild cases are often associated with pain or difficulty when urinating in a public bathroom. For both men and women, it is exacerbated by stress.1 A Harvard University study concluded that “the impact of interstitial cystitis on quality of life is severe and debilitating.”2 The condition is now officially recognized as a disability.

The cause of this disorder seems to be complex and is largely unknown. However, we believe it is due to a sympathetic nervous (fight/flight) system constriction of the smooth muscle in the bladder and urinary tract. Exposure to childhood trauma is associated with a six-fold increased risk of developing the disorder—about the same correlation as with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and irritable bowel syndrome. As many as 70 percent of these individuals have suffered physical and/or emotional abuse as compared to 15 percent of healthy individuals.3 And this is not even taking into account other traumas such as medical traumas and accidents. There are strong indications that both irritable bladder and fibromyalgia are trauma related.

The various breathing and pendulation exercises you have practiced for other pain syndromes are applicable to this disorder as well. In addition, we suggest you try sitting on a gymnastic ball with your feet shoulder-width apart, contacting the floor to maintain an easy balance. Then become aware of how the ball contacts and supports the floor of your pelvis as you breathe in. With your out-breath, just allow the floor of your pelvis to sink into the ball. This particular exercise is often quite useful in working with PMS and other types of pelvic pain.

One of the most challenging pain conditions is reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), which is now, generally, called chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS). It is another pain condition related to regulatory problems in the autonomic nervous system. Sometimes the pain is in one part of the body and will appear to generate a freezing cold sensation, while another part of the body will feel burning hot. These temperatures can actually be felt on the outside of the body as well as on the inside. This kind of pain is called “exquisite pain.” The word “exquisite” is used here in a negative sense, as in “exquisitely painful.”

One approach that has been very successful with CRPS/RSD is the use of very light touch across the limb, joint, or area involved. Some Somatic Experiencing therapists have developed this method. In this case, touch is used to help amplify a person’s ability to get under the pain and experience their underlying non-pain sensations, while also providing support to the individual to keep exploring.

An example of this approach was used with Michael, a ninety-two-year old man diagnosed with neuropathy, which is often one of the symptoms of CRPS. He had classic symptoms in his extremities—burning sensations in his arms, hands, legs, and feet. He was guided to do some simple tracking of sensations, and two incidents came up which greatly surprised him. Michael had been a marine under fire during World War II and, many years later, also survived a fatality-causing tornado that threatened his home. He had never talked to anyone about these experiences. He had difficulties feeling into the pain, typically reporting “feeling nothing” or “feeling the same.” Eventually, he noticed that when he achieved awareness of the sensations related to these two traumatic events, and amplified them slowly through touching these areas gently with his hands, his pain level went from 8 to a pain level of between 2 and 3.

The typical medical thinking is that neuropathy and other types of CRPS cannot be reversed. Many medical practitioners tend to be very frustrated about CRPS, sometimes even venting anger with comments like, “Wait a minute, what’s going on here? Your pain was in your left knee last week, now you say it’s in your right hip?!” The shifting from place to place in the body, known as migrating pain, may be an expression of involuntary dysregulation in the autonomic nervous system. Our position is that even if this kind of pain is caused by some structural change in the tissues, when the patient can achieve better self-regulation, pain levels can dramatically change.

It’s really important to appreciate that CRPS is not all in your head. Knowledge can be empowering, especially if you understand that migrating pain has a cause, and that the cause is not that something is wrong with you, but occurs because of the pervasive dysregulation. There are special skills that you need to learn in order to work with these elusive pain sensations to achieve regulation and relief.

One effective way of working with CRPS or other types of migrating pain is to learn to connect the different sensations and regions of the body that are linked with pain. The following is an exercise that can be used whether you have CRPS or other types of pain that affect different parts of your body.

Take a few moments now to explore various areas of discomfort. If helpful, use your hands to gently touch those areas of your body as Michael was taught to do. Place your hand gently on one area at a time and imagine that you can breathe into it very gently. Notice what shifts with the sensations.

Then practice a special kind of pendulation (see exercise, track 13) by connecting these pain areas together. For example, if you are experiencing pain in your foot and also along the sciatic nerve and in your lower back, take time to breathe into one area and then, one by one, into the others. Now use your attention and focus to move from one of these locations to another. For example, you could first bridge from your foot to the sciatic area, noticing the effects that occur, then shift back and forth several times, noting what becomes different. Next, you could bridge from your sciatic area to your lower back, going back and forth between each of these two locations several times.

Finally, use your breath to help this along. Breathe in when you connect with one location, then breathe out when you connect with the second (or the reverse: breathe in when you connect with the second and out when linking to the first area). What do you notice after shifting in this way?

If needed, you can add an area of relative comfort or neutrality as one of your bridging destinations. What difference does this resource make? You may want to take a little time to write about your experiences of this mini-exercise in your pain journal.

Chronic depression is emotional pain often related to separation, loss, abandonment, and insecure attachment relationships. Depression can also be a byproduct of chronic pain because we can become worn down by intense and unrelenting discomfort. Since depression so often accompanies many pain conditions, antidepressants are often included in pain treatment protocols.

The biggest challenge involved in resolving depression is to thaw the freeze or immobility response on a daily basis by mobilizing toward action within your body and in your greater life. Taking a fifteen to twenty minute walk a couple of times a day can begin to make a difference. It’s helpful to understand that depression, especially when viewed from its close relationship to the freeze response, is a way of shutting down as a “last-ditch” form of protection. Although there is no specific way of determining whether a given case of depression is linked to unresolved immobility, some of the signs of this connection are a lower blood pressure and slower heart rate and respiration under stress. Dizziness and light-headedness can also be symptoms.

When SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) such as Prozac came into mainstream use, experts suggested that depression must be a disorder of insufficient serotonin. Although there’s some truth to this premise, what’s interesting is that a brisk walk around the block can elevate serotonin levels as effectively as medication. There is no cost involved in walking—nor are there any bothersome side effects.

You might begin by making choices that allow you to be more active in your body, such as gentle stretching, practicing simple yoga poses, or taking a short walk when you would rather collapse and lie in bed. Even more effective is to engage in action that involves the company of another person, such as playing with a child, going to a “safe” non-triggering movie, or dancing to your preferred type of music. In this case, activity is especially important at times when you least feel like being active.

Taking action to raise serotonin levels is only part of the solution, however. People who use exercise (or anti-depressants) to help regulate their neurotransmitters may become less depressed, but sometimes will experience more anxiety. The question then becomes how to deal effectively with the anxiety that often surfaces so as not to flip back into the depression.

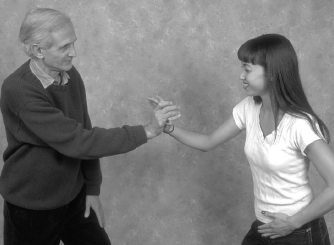

It is important to develop simple, effective ways of self-soothing that allow you to access a sense of safety, strength, and support through your body experience, and which support movement into safe action. For example, if you have a friend or partner who is willing to help you, ask that person to stand facing you partly, with one leg in front of the other for support, and offer you one or both hands for you to push against with your hand (or hands). If it feels safe to do so, you can name what you are pushing against that triggers a depressive reaction in you (for example, pain, discouragement, a critical boss, or a mysterious new pain symptom).4

Figure A

Figure B

Naturally, if your pain increases, stop and rest. Debrief afterward by communicating what you experienced. You might want to write about this practice session in your pain journal: specifically, what did you learn about how to work with your depression?

Although breathing techniques can be very helpful with depression, deep breathing techniques sometimes cause an increase in anxiety, and can even incite a greater collapse into depression or helplessness. So understand that if this happens, just rest and then try it again, if you like. Very often, just a few moments of rest is all that it takes for your nervous system to come one more step out of the depression. In addition to circle breathing (see exercise, track 2), you can also learn to create a body safe place by first identifying a place in your body that is a little more comfortable than any other. Once you find this, breathe gently and normally into that area of the body to better connect with a sense of safety or strength or comfort. With practice over time, your body safe place can become a touchstone for connection that is reliably positive.

Since depression is linked with the freeze response, as the response begins to “thaw,” different layers of distress, including hyperarousal, rage, grief, or fear may surface. In these cases, it is often helpful to use the breath to regulate the distress by voicing a sound such as “voo” during a slow exhalation. This tends to help titrate or naturally dilute the surfacing emotions that often can feel overwhelming and uncontrollable. (See Voo Breathing exercise, track 6.)

To help further with a hyperactivated or anxious state that can emerge when the freeze of the depression begins to shift, you can use the same pushing practice with a partner described earlier to gently release the anxiety.

Rage and aggression are also commonly connected with depression. Studies and clinical observation have indicated that some types of depression are caused by rage turned inward against the self. It’s very important to know how to work with rage in a contained way. Imagery can be very helpful in beginning to process rage in a safe way. Following is a useful application of imagery. Even though this is a fantasy, it can be unsettling at first. If it seems too much for you, just skip over it for now.

Ask yourself the question, “If my rage could be expressed right now, what might that look like? What color might it be? What would it want to do? Who (or what) would be the target of my anger?”

Sometimes, just by looking from a distance at one aspect of your anger or aggression, you can envision or fantasize expressing it. Would you like to pound the source of your anger to a pulp? Would you like to cut it up with a knife, or stomp on it until nothing is left, until it is completely destroyed? As you connect with any of these images, what do you notice in your body right now?

Working with aggression and impulses with the goal of complete destruction at least allows the acceptance of these taboo emotions. Then you can begin to understand that rage is indeed linked to the impulse to destroy, but is also a feeling and an image of destroying. This is different than actually hurting someone else or hurting yourself. So while the imagery can be a bit scary at first, with a little creative practice, it can become exhilarating.

In addition to channeling aggression and dealing with anger (in resolving depression), the most important interventions are related to helping you develop the skills to socialize and accept social support. This allows your ventral vagal,5 or social engagement system, to re-engage and provides additional resources to counter the depressive, isolating tendencies that can take you back into the state of freeze and collapse. The right kind of support group can be invaluable in reinforcing and strengthening social skills. I once led a pain group, and by the end of the night, we were all laughing uncontrollably at each other’s gallows humor. Such laughter, by the way, is a great way to release endorphins, the body’s built-in pain control agents.

If you are frozen in chronic depression, it is necessary to take very small steps toward recovery. Maybe you can begin by discovering what gives you even a tiny bit of pleasure, or what is at least reliably neutral. If you cannot find this small island of “OK-ness,” a professional might help you to learn to take small actions to generate new experience. Also medications can sometimes give people enough of a lift to mobilize them to use the Freedom from Pain tools more effectively.

Are you willing just one time when you get up in the morning to put on some gentle music to accompany some slow easy movements and stretching instead of going back to bed, just to find out what that feels like? We can’t predict how that will feel to you, but do you have anything to lose? We can predict how constricted life will remain if you continue to follow your usual patterns.

It’s also important to remember that there may be a great deal of shame embedded in depression. Shame is often coupled with helplessness and collapse. You may feel shame in asking for or receiving the level of help and support you really need and in allowing others to see your imperfections and helplessness. Feeling shame can send you deeper into a state of withdrawal and collapse. Learning to identify, feel, and regulate the sensations related to shame, however, can help decrease your pain and depression.

One of the most effective types of intervention with chronic depression, as with chronic pain, is mindfulness. An example is learning to develop what psychologist and lay Buddhist priest Tara Brach calls “radical self-acceptance.”6 This is a truly radical practice because at the moment that you are least able to give yourself acceptance, you are called on to give complete and authentic acceptance to yourself, which can result in a conflict-free moment of acceptance and love for yourself.

Here’s a three-step method that can help you develop radical self-acceptance. First, you must be willing to pause and notice that you are not accepting yourself . . . and to accept your lack of acceptance for the time being. There are a number of ways to notice this: there’s the voice you hear in your mind telling you that you’re no good, or you may find yourself disconnecting or dissociating from body experience when you don’t want to accept or feel it. Another way might be to notice the unwanted shame triggered by devaluing social interactions that make you think that you are worthless or unlovable, thus compounding the lack of self-acceptance you feel. This first step, called the “sacred pause,” is often the most challenging. You must be willing to stop, as Brach suggests, and simply notice your lack of acceptance.

Step two is to make an inner commitment to turn your mind toward some form of acceptance, whatever is possible at a given moment. For example, you can shift from “I am worthless” to “I feel worthwhile when I am at work, or when I am with my children.”

And step three is to continue to repeat the first two steps as long as it’s helpful. Understandably, like life itself, this is an endless practice. You might want to work with this as a mini-practice exercise and note your results in your pain journal. The following exercise may also provide additional practice for you.

One practical example of how to turn your mind toward self-acceptance is derived from what is called Energy Psychology. This technique is used to clear reversals, which in energy terms are disturbances that usually come from an inner conflict where the person is both moving toward a positive change and moving away from this change at the same time.

To clear an energy reversal, we use positive self-affirmations while stimulating specific energy points along one of the meridians or energy pathways in your body. To practice this, find your so-called neurolymphatic points by feeling your collarbone at your neckline, then coming toward the midline of your body, from that point moving one inch down toward your feet on the left side (or both sides), and then over four to six inches toward your shoulder. If you encounter the fold of the shoulder, you’ve gone too far. If you rub in the correct area, you’ll usually feel tenderness.7 (If these directions sound confusing, please see diagrams referenced in the endnote to clarify this practice.)

The approach is to rub these points on either side of the chest (but especially on the left side) because this is believed to help release toxins and stress. As you rub those points on your chest, you say a simple affirmation such as, “I deeply and completely love and accept myself, even with all my problems and limitations.” This clearing technique requires you to say this or another similar phrase three times.

The affirmation works because it expresses your positive intentions toward yourself even if you are not able to actualize them or believe them yet. You can also add other specific affirmations like, “I deeply and completely love and accept myself even though I don’t think I’ll ever be free of depression” or “I deeply and completely love and accept myself even though I hate the way I am right now,” or whatever is true at the moment. It’s important to word the main affirmation so that you can really resonate with it; for example, “I want to deeply and completely love and accept myself ” or “I wish I could deeply and completely love and accept myself.”

We can understand why affirmations work by examining research conducted in neuroplasticity, which has demonstrated that our physical reality is formed from past experience.

In other words, whatever symptoms or problems we have, including pain, as well as whatever strengths we have, are much more based on experience than we ever thought was true. Most of us subscribe to the theory that DNA genetically determines who and how we are in the world. Neuroplasticity research has turned this theory on its head and gives us an entirely new way to look at the impact of our thoughts and beliefs.

We know that thoughts literally change brain chemistry. Research indicates that the chemical composition of the body can change in relation to a specific thought within twenty seconds.8 This shift can be measured in a number of surprising ways. One way is to measure the acid or alkaline effect the thought has on the body.

If we’re really focused on a negative thought or limiting belief, our nervous system will send messages almost immediately to our muscles, which will then constrict. Negative thoughts affect our thinking mind as well so that we can’t think well and can also increase anxiety. In addition to external threats that can activate the freeze of depression, we also need to be aware of internal threats, such as negative thoughts or negative beliefs coming from inside us.

Cells in the brain that fire together get wired together. If we have thought or experiential connections that aren’t used very much, those will be eliminated. Those brain cells that are wired together create a neuronal network; in the case of affirmations, a positive “higher self ” network is generated that can automatically be set off when we encounter a negative trigger in everyday life. So affirmations can bring important changes in self-acceptance if you use them only a few times. If you use them regularly, you’ll get even more results because they create a special wiring and firing pattern that results in a new neuronal network.9

Marti has struggled with depression for as long as she can remember. Her mother was hospitalized with severe postpartum depression just after Marti’s birth and her grandmother took care of her during that time. Marti’s sense was that the roots of her own depression were in the loss of her nurturing grandmother and the intrusion of her mother’s anxiety when she returned to the home several months later. Marti had fragmentary images of both her mother and her father physically abusing her throughout her childhood.

As an adult, Marti became a competent attorney in human rights, yet in her early forties, she developed fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, migraine headaches, and severe depression. Although antidepressant medication helped her somewhat, Marti continued to struggle with this quartet of syndromes and ultimately went on disability because she could no longer work.

As we explored the connections between these health problems, we decided to use affirmations to begin to shift these patterns in an attempt to boost her energy system. The affirmations that seemed to work best for her included: “I deeply and completely love and accept myself even though I’m depressed and have pain most of the time”; “I deeply and completely love myself even though most of my life I have believed I’m unlovable . . . I forgive myself for this conclusion”; “I deeply and completely appreciate myself even though my family has never known how to appreciate me.”

Marti found that she could remember to say the affirmations while rubbing the neurolymphatic point on her left chest whenever she felt her pain and depression increase. Although the positive results were subtle and slow, over time she felt more stable and was able to decrease the dosage on both her antidepressant and pain medications. She began exercising and then used the affirmations to manage the pain flare-ups that sometimes resulted. Marti’s evaluation was that “many tools helped me to reclaim my health, but the affirmations were easy to remember to use and brought instant relief. I could use them in just about any situation and the results were almost always positive.”

If you’d like to practice using affirmations to help you manage your depression and pain, take a few minutes and try out a few basic ones. It’s good to start with the basic phrase, “I deeply and completely love, accept, and appreciate myself even though . . . (add your own words here).” Leading with a positive affirmation allows you to hold your depression and pain in a more balanced and positive way.

Practice using your affirmations for several days when you are aware of an increase in pain or depression. Make sure the words you choose fully resonate with your body. What changes do you notice? Note your results in your pain journal.

Don’t be discouraged when you don’t get immediate results from your affirmation. Once I felt completely overwhelmed by the vast amount of work I had to complete, while at the same time I had a wrist injury that was aggravated by typing. When I thought about trying an affirmation, I heard the words in my mind, “That won’t do any good, you just have to do it.” Then the following affirmation spontaneously arose in my mind: “I can ask for help, I don’t have to do it alone.” I chuckled and then called a friend and asked if he would be willing to type as I dictated. The specific affirmations that you will find for yourself are limited only by your imagination, creativity, and willingness to seek ways to promote your healing process.