Gagné, Charles: “Low-Risk” Hit Man – This Quebec man was regarded by federal officials as a low-risk parolee when he murdered Toronto boxer Eddie Melo and Melo’s friend Joao “Johnny” Pavao.

The National Parole Board granted Gagné a day pass on December 12, 2000, even though he was serving a ten-year sentence for robbing a grocery store in 1995 with an AK-47 assault rifle while unlawfully at large. “The board is persuaded that your risk is not undue upon such a release,” the board ruled, although the decision added, “Your criminal history includes a number of weapons offences, which involved guns on all occasions and negative associates.”

Calling his previous behaviour “impulsive” and “thrill-seeking,” the parole board decision continued, “As well, you have demonstrated a comfort with a criminal lifestyle that includes guns and negative peers who make ‘big promises’ of easy money.” Nonetheless, the board concluded that Gagné, then twenty-seven, had mellowed since he stuck up the supermarket with the AK-47. “Your institutional performance over-all has been good, which the board takes as evidence that you are less impulsive and better able to choose your associates, … all of which suggest that risk is manageable.”

Four months later, on April 6, 2001, Gagné was in a Mississauga parking lot, firing close-range shots into Melo and Pavao. He hadn’t met either man before but was willing to end Melo’s life for $75,000, and the promise of future criminal work. He threw in the Pavao murder for free because Pavao was a witness.

In September 2003, Gagné turned on the man whom he said had hired him, a long-time neighbour and sometime friend of Melo. For this, Gagné was allowed to plead guilty to two counts of second-degree murder, which offered the hope of further parole in twelve years. A first-degree murder conviction would have meant no parole for twenty-five years.

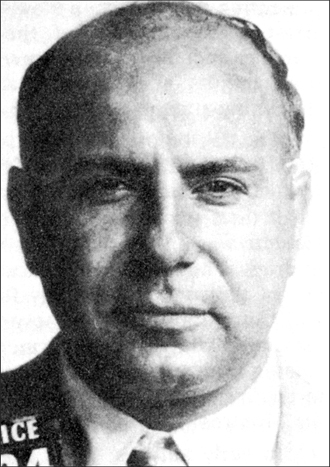

Charles Gagné

“The Crown is accepting Gagné’s plea to second-degree murder, in what is clearly a first-degree murder case, because of the need to call Gagné as a Crown witness in order to seek justice in that related case,” Crown prosecutor Stephen Sherriff told the court. Gagné’s lawyer, John McCulligh, said his client, who was now HIV positive, “renounced the life he lived.”

On December 16, 2003, a man from Melo’s old west Toronto neighbourhood, fifty-year-old Delio Manuel Pereira, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit murder in connection with Melo’s contract murder.

Pereira admitted that the plot involved three other men, including Gagné. His sentencing will not take place until after June 2004.

At the time of Gagné’s arrest on July 14, 2003, for the Melo and Pavao murders, he was on a day pass from a prison in Gatineau, Quebec, where he was serving a new ten-year sentence for aggravated assault for shooting up a Quebec chalet while collecting a drug debt.

See also: Eddie Melo.

Gagné, Stéphane “Godasse”: Football Team – The first time Gagné met Hells Angels boss Maurice “Mom” Boucher was in the mid-1990s in a downtown Montreal store. He instantly recognized Boucher and passed him his pager number, asking Boucher to call him.

Gagné, whose nickname means “dirty shoe” in French, had a twelve-year criminal history of theft and drug convictions. After the chance meeting with Boucher, he was approached by a member of the Rock Machine while in the Bordeaux Jail in Montreal. The Rock Machine member asked him to stomp on a picture of Boucher, and Gagné refused.

“I was an independent [drug dealer] at this point in the biker war,” Gagné later told court. “They asked me to choose between the Rock Machine and the Hells Angels and I chose the Hells Angels.” Gagné was quickly hurt in a fight, but took his revenge later by attacking a Rock Machine inmate with a pipe. Transferred to Sorel Detention Centre, he met Boucher again, and they soon were taking Alcoholics Anonymous and drug-rehab sessions so that they could talk.

When they were both free again, Gagné stole a Jeep Cherokee for Boucher. Soon, Gagné was moving in Boucher’s circles. On weekends, he would help bring the ti’gars, or “little guys,” who were the lowest-ranking dealers in their crews, to Boucher’s home. The ti’gars would clear his yard of unwanted foliage and bushes, making the place tidier and, far more importantly, making it more difficult for intruders to hide.

During get-togethers for les hells, junior bikers acted as gofers and waiters. It was a feudal arrangement, and lower-tier bikers like Gagné had to make sure their higher-ups were properly fed and refreshed. “As long as there are members who are up, you stay up to serve them,” Gagné said.

Stéphane Gagné

Gagné soaked up the nuances of biker culture, such as how, when bikers of equal rank met, they would shake hands and hug, patting each other’s backs. However, a lower-ranking biker must not do that to a superior. Someone of his rank had to keep his hands off the gang patch on the back of a senior biker’s vest.

Gagné felt he was part of something big now. One meeting in 1997 was at Bistro à Champlain, which had a 35,000-bottle wine cellar. Seventeen bikers dined on foie gras, Bordeaux, and Burgundy, then paid the bill of more than $8,000 in cash.

To explain how they could own houses and cars without real jobs, the bikers invested in a range of businesses, ranging from dry cleaners to taverns. There were also fake jobs, and Gagné arranged for a company to issue him bogus pay slips and T-4 forms. Boucher sometimes claimed in court cases that he was a used-car salesman working on commission. “Me, I’ve never seen Mom sell a car,” Gagné later told the court.

Gagné felt as if he belonged in Boucher’s world, and even named his son Harley-David after the Harley-Davidson motorcycles the bikers rode. “I wanted to make money and become a Hells Angel,” he said. “I’d go out each night, buy rounds, give money to my relatives, drive the latest car of the year.”

Gagné said that Pierre Provencher of the junior club, the Rockers, recruited him to the Angels’ “football team,” a euphemism for the Angels’ death squad. Provencher was among a group of Rockers fighting to gain control of drug turf in Verdun during the late 1990s. The Rock Machine was already well-entrenched in the area, and the battle for Verdun became a focal point in the biker-gang war.

In early 1997, Gagné and another biker tried to kill a Rock Machine drug dealer in the woods. They shot him and tried to suffocate him when he kept talking. To Gagné’s shock, the man was somehow still alive the next day.

In June 1997, Gagné met with Boucher again, and was told to stay out of jail for a while. “He told me it was important that I stay clean for other things than stealing cars,” said Gagné. “For more important things, the big jobs.”

The “big jobs” included murdering an unarmed mother simply because of her job as a prison guard. On June 26, 1997, Gagné and André “Toots” Tousignant shot guard Diane Lavigne dead as she left her work. She hadn’t done anything personally to offend the gang. They didn’t even know her. The mother of two was murdered simply because she was a jail guard, and the murder was part of a plan of Boucher’s to destabilize the justice system.

Two days later, a twenty-nine-year-old civilian employee who conducted Alcoholics Anonymous meetings at St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in Laval, north of Montreal, was wounded in similar circumstances. Two men on a motorcycle fired four times at him, but he escaped with severe injuries.

When another guard was murdered, Gagné asked two more-senior bikers about the attack. They didn’t say exactly, but Gagné left the conversation with the impression that they had a hand in it. They were later promoted to the Nomads, the highest Hells Angels rank, before going to jail on other murder charges.

Gagné later told police that he was preparing to kill defence lawyer Pierre Panaccio when he was arrested December 5, 1997. According to Gagné, Panaccio fell out of favour after influential members of the Rockers accused the lawyer of defending them poorly, and wanted to recover some or all of the advance they gave him. Gagné said the issue was brought to the attention of Boucher. As Boucher and Gagné added up drug proceeds, Boucher wrote on a message board, “Must do Pinocchio.”

When Gagné was arrested for the Lavigne murder, he pleaded guilty and was given a twenty-five-year sentence. He cut a deal with the Crown for $140 a month to be paid to his prison canteen privileges and $400 a month for his son. For that, he agreed to be the Crown’s main witness in Boucher’s first-degree murder trial in the spring of 2002, for the murder of the two prison guards.

Gagné learned of the Hells Angels leader’s conviction as he watched TV behind bars. “I shouted ‘Yes’ and went into the prison yard to work out and get some sunshine,” Gagné recalled. “Justice has been done.”

See also: L’Asssociation des témoins spéciaux du Québec, Maurice “Mom” Boucher, Diane Lavigne, Nomads, Rock Machine, André “Toots” “Peanuts” Tousignant.

Galante, Carmine: Deadly Ambassador – Born in 1910 in the slums of East Harlem, New York, Galante was the son of an immigrant fisherman from the town of Castellammare del Golfo in Sicily. That scenic community was also the birthplace of American Mob bosses Joe Bonanno of New York City, Stefano Magaddino of Buffalo, Joe Profaci of Brooklyn, and Joe Aiello of Chicago. Soon Galante (whose name is often also spelled Galente) would follow in their footsteps.

By the age of ten, he was an incorrigible delinquent and by seventeen, he was in Sing Sing Penitentiary in Ossining, New York, for assault. At twenty, he was accused of the murder of a police officer, but the case was dismissed for insufficient evidence. In 1939, still under thirty, he was paroled on his third prison stint – this one for assault and robbery.

By then, organized crime in New York City was governed by the Mafia Commission, which oversaw the activities of the five major families, and Galante lusted for a strong role in the new order. He freelanced his criminal services for underworld bosses Bonanno, Profaci, Vito Genovese, and Lucky Luciano, until Genovese gave him his big break. Genovese wanted Carlo Tresca, the New York editor of The Hammer newspaper, murdered. The feisty anti-fascist newspaperman had infuriated Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini, and Genovese wanted to curry favour with “Il Duce.”

Shortly after the murder, Galante was Joe Bonanno’s driver, a position of some status. It wasn’t long after that, in 1952, when Galante moved north from New York City to Montreal. He brought with him a fearsome reputation, top-level Mob contacts, and a desire to escape the relentless publicity caused by the Kefauver hearings on organized crime in the United States. His job was to expand the operation of the Bonanno family north.

Galante wanted to make Montreal the focal point in the drug trade. Montreal had great promise for the American underworld, if someone could bring some measure of order to it. There was the lure of the long, inviting shoreline along the St. Lawrence, harbours for oceangoing ships, and fast highways on the 385-mile drive to the rich drug markets of New York City.

Carmine Galante

At that time, branch plants were coming to Canada in the auto, radio, and appliance industries, and Galante wanted to do the same thing with organized crime. He worked out of an electronics firm, guarded by Frankie Carbo, considered the dean of boxing. Soon Galante was pulling in protection money from underworld gambling dens and blind pigs (after-hours drinking spots).

His boss, Bonanno, was particularly interested in gambling profits. Police estimated that Galante helped collect some $50 million yearly in gambling profits in Montreal, earning him the titles of Bonanno’s underboss and foreign minister.

There was clearly a shakeup underway in Montreal. Gambler Frank Petrula brought a huge amount of heat on his associates when police raided his home in 1954 and found a notebook that contained a list of municipal politicians and journalists who were bribed a total of $100,000 to defeat then mayoralty candidate Jean Drapeau, who was a reformer against the Mob. Petrula was never forgiven for this sloppiness, and it was feared he might start co-operating with authorities. Soon, he was missing and presumed dead as the era of gentlemen gamblers like Petrula was gone, replaced by more hardened business people like Galante.

Galante didn’t last too much longer in Canada, but by the time he was deported to New York City in 1955, he had firmly planted the Bonanno family flag in Montreal. Vic Cotroni was installed as its branch-plant manager, and this relationship was cemented when Galante became godparent to one of Vic Cotroni’s children, and vice versa. Galante was five-foot-five, an inch taller than Cotroni; together, the two were the little Napoleons of the Montreal underworld.

Also at the top of the Cotroni family was pizzeria owner Luigi Greco, a Sicilian. With the Calabrian Cotroni and the Sicilian Greco working together atop the Montreal Bonanno family, there was a lid to any ethnic fighting between Sicilian and Calabrian mobsters.

Galante was arrested along with Bonanno at the 1957 Appalachian Mob meeting in upper New York State, when state troopers and federal agents sent the sixty or so crime delegates fleeing through the bushes. Publicity from this forced FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to admit the existence of the Mafia, which he had denied for almost three decades.

Galante was also in Palermo in 1957 when plans were set up for the French Connection heroin route, to bring Turkish opium to Marseilles, where it was refined, and then shipped to New York City and Montreal. Others in attendance included Bonanno, Lucky Luciano, Sicilian crime boss Salvatore Greco, rising Sicilian Mafioso Gaetano Badalamenti, and Tommaso Buscetta, who later became one of the Mob’s most dangerous turncoats.

Frank Petrula

Galante also used this trip to spread the word that ambitious young Italian Mafiosi could come to New York and form their own crews under his wing. By the mid-1960s, many of these newcomers were setting up businesses or working in bakeries and pizzerias around Knickerbocker Avenue in Brooklyn. They became known as “Zips” for the quick way they talked, and ultimately they would determine Galante’s own fate.

Galante also worked on a Cuban drug route through Havana and Florida, getting permission from the Batista government to use Cuba as storing spot for mainland-bound heroin. Although he was unschooled, he could speak Spanish, French, and Italian dialects fluently, which helped him set up drug deals. His habit of never writing things down made him hard to convict.

He was often seen with his pants held up by a rope, although he also had hand-tailored suits and loved smoking Don Diego cigars, which earned him the nickname Mr. Lillo, which translated to “Mr. Cigar.”

He had a mistress of more than twenty years, but considered himself a Roman Catholic, and refused to divorce his wife. Instead, he made an underling marry his common-law wife to legitimize their children. Of his so-called religious beliefs, an associate was once quoted as saying, “Lillo would shoot you at noon during high mass.”

He was able to walk around New York City with no bodyguards, as there were so many police tailing him he didn’t need them. He gave his police shadows a workout, changing cars as often as other men changed shirts. At one point, police followed him to Disneyland, where they found him riding go-carts with another mobster.

Though unschooled, he was said to enjoy the writings of Descartes and St. Augustine, although he was never bogged down by conventional morality. A prison psychiatrist diagnosed him as a psychopath, a mass murderer who managed to see himself as a good Catholic and a good patriot. Detectives would estimate he had been involved – directly or indirectly – in some hundred underworld executions, and that he carried out eighty of them himself.

He was rumoured to have dreams in the late 1970s of uniting New York City’s five families under him, as boss of bosses. There had been a vacuum left by the death of Carlo Gambino, and Galante hoped to fill it himself. Not surprisingly, there were plenty of whispers that other mobsters – including those in his own crime family – were out to kill him and his ambitions.

In 1979, Galante told a journalist, “No one will ever kill me – they wouldn’t dare. If they want to call me boss of bosses, that’s all right. Between you and me, all I do is grow tomatoes.”

Four days later, he was murdered at age sixty-nine. The killers were from his crew of Sicilian-born “Zips,” whom Galante considered his own private army.

As a final indignity, the church refused him funeral mass.

See also: Joe Bonanno, Vincenzo “Vic the Egg” Cotroni, French Connection, Luigi Greco, John “Johnny Pops” Papalia.

Galliardo, Don Totto: Postwar Don – He ran an established Sicilian crime family in southern Ontario after the Second World War, and a police report from the time called him “one of many italians [sic] who never work, living on the proceeds of bootlegging and criminal activities.” Totto Galliardo’s brother Joe was the family enforcer. Based in Toronto’s downtown Ward district (around York Street in today’s financial district), his allies included a powerful Niagara Falls Sicilian crime figure, named in police reports throughout 1920s as Don Simone, and his rivals were the Calabrian Mob.

See also: Interned in the Second World War, Giuseppe “Joe” Musolino, Bessie and Rocco Perri.

Gang of Eight: Legal Debacle – In the early 2000s the federal Justice Department decided to make their suit against this gang a test case for Canada’s newly minted anti-gang law, which made it illegal for anyone to be part of a criminal organization.

For ten months, Edmonton city police and RCMP tapped the phones of the members of an alleged crime family. In all, the police taped 281,000 conversations, very few of which were in English, but rather Cantonese, Mandarin, Vietnamese, and Chiu Chow, a dialect spoken in China’s Guangdong province. To make things more complicated, many of the conversations involved street code and slang. More than 65,000 person-hours were spent between 1999 and 2002 to translate, transcribe, sort, and photocopy those conversations.

In September 2003, the case collapsed under its own weight, as Justice Doreen Sulyma stayed charges against eleven more defendants of the alleged crime family, ruling that things had dragged on so long their right to be tried within a reasonable time had been violated. At that point, they had been awaiting trial for four years, and the starting date for any trial was well off in the future.

Three more defendants in the case pleaded guilty to lesser charges. That left eight – the so-called “Gang of Eight” – still awaiting trial.

The Edmonton Journal concluded that “the police and the Crown ended up with too many defendants, too much evidence, too many witnesses, and not enough resources to cope with any of it.”

The Journal also noted that, in September 1999, the same month the police arrested the defendants, management consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers completed a confidential report for the federal cabinet that said that the RCMP’S ability to fight organized crime was in peril because of five years of budget cuts. What the force needed was 189 more officers and $125 million to effectively fight organized crime, the report concluded.

See also: Manitoba Warriors, Nomads.

Gargantua: Underworld Slaughter – In 1975, thirteen people were herded into a storage room in Montreal’s Gargantua nightclub. Some were shot, but most died of suffocation when the building was set on fire by underworld figure Richard “The Cat” Blass.

Blass, a prison escapee, was really at the bar to kill two men he blamed for putting him in jail. The other eleven victims were eliminated as potential witnesses.

It was Canada’s worst mass murder until December 6, 1989, when Marc Lepine, twenty-five, walked into L’École Polytechnique, the engineering school of the Université de Montréal, and methodically murdered fourteen women.

See also: Michel Blass, Richard “The Cat” Blass.

Ghost Shadows: Student Extortionists – By the early 1990s, this gang had amalgamated with the 14K Association in Toronto and were rearing their heads at the expense of the rival Kung Lok. Many Canadian Ghost Shadow members belonged to wealthy families and were in Canada on student visas. Others were waiters and busboys who hoped that a connection with the Triads would win them respect.

Gang members often assaulted fellow students, then asked for “lo mo” – slang for extortion payoffs.

See also: Big Circle Boys, 14K Association, Kung Lok, Sun Yee On, Triads.

Giglio, Salvatore “Little Sal”: International Troubleshooter – He moved north to Montreal from New York City in 1956 to watch over Bonanno family interests after the deportation of Carmine “Mr. Lillo” Galante.

Giglio grew so close to Montreal criminal Lucien Rivard that Rivard was his best man when Giglio married a waitress at El Morocco, a nightspot run by a Cotroni family lieutenant. Giglio’s duties included making sure the heroin traffic of the Cotroni family and Rivard ran smoothly. He also assisted Cotroni and helped to connect him to other significant underworld figures. Giglio paid visits to Rivard in Cuba in the 1950s, before Rivard was deported back to Canada.

See also: Joe and Bill Bonanno, Giuseppe “Pep” Cotroni, Carmine Galante, Lucien Rivard.

Gill, Peter: Freedom Lover – More than fifty Vancouver criminals had been slain in a gang war in the 1990s when Gill appeared in court to face murder charges, which included brothers Ranjit “Ron” and Jimsher “Jimmy” Dosanjh, heads of a lower B.C. mainland criminal organization, who were gunned down within six weeks of each other in early 1994. One of the victims of the gang fighting was shot dead at his own wedding, and another inside a barber shop. Yet another hit was in front of three hundred people in a crowded nightclub, but no witnesses came forward.

Gill walked free from the murder charges, and later it was learned that he had had an affair with one of the jurors, Gillian Guess.

In May 2002, Gill was found guilty of obstruction of justice for intimidating a witness in an assault case in Calgary, his new hometown.

See also: Gillian Guess, Bhupinder “Bindy” Johal.

Ginnetti, John Ramon “Ray”: Rough Company – Ray Ginnetti wouldn’t have minded that a dozen Hells Angels wore their colours to his May 1990 funeral, including sergeant-at-arms Lloyd Robinson.

Ginnetti, who began his career as a car salesman in East Vancouver, loved the high life in Vancouver nightclubs and eateries, and made headlines once by getting into a restaurant shoving match with actor Sean Penn. He often hinted at his connections with organized crime (although was never a member of either the Mob or the Hells Angels), and boasted he earned his living by collecting on loans and by betting. Later, he worked as a stockbroker for several Vancouver brokerage houses, doing nothing to bolster the already-shaky image of the city’s financial traders.

Ginnetti was involved in promoting a questionable Vancouver Stock Exchange offering of a telemarketing company. When investigators raided it in 1986, they found a boiler-room operation, complete with phone banks, “sucker lists” of potential clients, and sales records. They also found a bag containing $50,000, but before they could confiscate it, a man grabbed it and threw it out the window to Ginnetti, who caught the loot and ran. Not surprisingly, the B.C. Securities Commission slapped a cease-trading order on the firm.

Ginnetti ceased trading altogether at the age of forty-eight, when someone shot him execution-style with a single bullet to the head from a .380-calibre semi-automatic handgun. His body was found by his wife of ten years, Barbara, on the afternoon of May 9, 1990. stuffed in a closet at their $750,000 West Vancouver home.

Shortly after Ginnetti was escorted to his grave by a dozen Hells Angels, police were investigating yet another gangland murder. On May 15, 1990, small-time Russian mobster Sergey Filonov, an accused cocaine trafficker who allegedly bragged about being involved in the Ginnetti killing, was himself slain.

The Filonov murder didn’t close the books on the Ginnetti hit. In June 1995, authorities charged thirty-five-year-old Jose Raul Perez-Valdez, who listed his home as Hollywood, California, with first-degree murder in connection with the killing.

At the time he was charged, Perez-Valdez, a Cuban American, was sharing living quarters with 1,800 other inmates in the federal penitentiary in Lompoc, California. As prisoner number 24900-086, he was serving a ten-year sentence imposed for a Seattle-area kidnapping and for possession of cocaine with the intent to distribute.

It would take a flowchart to follow who was killing who and why. Police concluded Perez-Valdez was a professional hit man, who, along with another Cuban, was hired to kill Ginnetti by a notorious Vancouver-area underworld enforcer, Roger Daggitt, who subcontracted the job after being hired himself to kill him.

Daggitt, thirty-nine, who was once described in court as a top enforcer for the Hells Angels, could offer no clarification on the murder, since he was killed himself in a Mob-style hit in the beer parlour of the Turf Hotel in Surrey, British Columbia, in October 1992. He was shot three times in the back of his head as his son watched.

No further details of the murder emerged when Perez-Valdez was charged in 1995, but tantalizing new information surfaced the following year, when hit man Serge Robin pleaded guilty to killing enforcer Daggitt. Knowledgable Vancouver Sun crime reporter Neal Hall wrote, “One theory is that Daggitt was killed [by Robin] to even the score” for the Ginnetti murder. Daggitt “had once worked as a bodyguard for Ginnetti,” Hall reported. “An informant told police Daggitt was the driver for the man who killed Ginnetti.”

Exactly why Ginnetti was slain remains unclear. Police wondered if perhaps there was a link between the murder and that of former stockbroker David Ward, who was found shot in the head in an idling truck in Vancouver in 1997.

See also: Vancouver Stock Exchange, David Ward.

Gold Key Club: Hamilton Hot Spot – If you had made it inside the east-end Hamilton hot spot at Main Street East and Wentworth, you would have rubbed shoulders with lawyers and business people and plenty of mobsters connected to “Johnny Pops” Papalia.

If you had looked across the street to a doughnut shop, you might have seen police craning their necks in an attempt to watch the goings-on.

The Gold Key Club was operated from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s by Papalia, who married, and then divorced, a waitress there. One of the club’s other hostesses, tall, blonde, comely Shirley Ryce, penned her memoirs, Mob Mistress: How a Canadian Housewife Became a Mafia Playgirl, with veteran organized-crime writer James Dubro.

Ryce, a bookie’s daughter, said she tried to show less-experienced mob women “how to act like a lady.” “There’s a lot more to me than just horizontal,” she explained to Toronto Star interviewer Susan Kastner.

See also: John “Johnny Pops” Papalia.

Greco, Luigi “Louis”: Historic Meetings – Greco and gambler Frank Petrula had been bodyguards for Harry Davis when Davis was a major narcotics trafficker in Montreal in the 1940s. After Davis was murdered in 1946, they hooked up with Vic and Giuseppe Cotroni and took over some of Davis’s rackets.

In 1950, Greco and Petrula were believed by police to have met with internationally powerful mobster Lucky Luciano that year in Naples.

Greco and Vic Cotroni backed Carmine Galante of New York when Galante enforced his rule of Montreal’s nightclubs, booze cans, gambling dens, bookies, hookers, and thieves. Greco and Cotroni’s younger brother, Giuseppe, led the Canadian contingent to the 1957 Appalachian Conference, a major Mafia get-together in upstate New York, which was crashed by police.

Greco was accidentally killed on December 7, 1972, in a freak solvent fire when he and some workers were replacing the floor of his north Montreal pizzeria. At his funeral, attended by the top figures of the Montreal underworld, his crony, Conrad Bouchard, sang Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria.”

Luigi “Louis” Greco

See also: Vincenzo “Vic the Egg” Cotroni, Harry Davis, Carmine Galante, Frank Petrula, Michel Pozza.

Grim Reapers: Prairie Bikers – The Grim Reapers motorcycle club was founded in 1967 as Calgary’s first outlaw motorcycle club. Two other clubs, the Rebels and the King’s Crew, followed in 1969.

One of the club’s most notable members was Gerry Weldon, who joined in 1973 and would later become president of the Edmonton chapter of the Hells Angels.

While with the Reapers, Weldon also publicly challenged police to charge his members or leave them alone. Police took him up on his challenge in June 1998, when Weldon, forty-seven, was riding his Harley-Davidson and stopped at a giant roadblock ten kilometres south of Edmonton. Auto-theft experts in the police traced the serial number of his Harley engine to one stolen three years ago in Surrey, British Columbia, and impounded the bike.

He had more luck in 1990, at the end of a twenty-nine-month fight to recover weapons that were seized by police. Police seized the guns when working to prevent what they said was an imminent war between the Grim Reapers and the King’s Crew.

In Calgary, police seized seventy rifles, including two AR-15 assault rifles, and four handguns, while Red Deer raids netted twenty-three rifles, twelve shotguns, four handguns, three crossbows, and an explosive device. In Edmonton, police scooped up twenty-two rifles and shotguns, three semi-automatic weapons, a flintlock musket, and ammunition. All of the weapons seized in Edmonton had valid registrations.

Police then said they believed there were tensions in Alberta because the Hells Angels were trying to open up an Alberta branch, and were deciding whether to hitch their fortunes to the Grim Reapers or the Rebels.

Ironically, when Weldon got his club’s guns back in 1990, he praised the legal system, saying, “In the end, it’s the judges that decided. It’s in the courts where we got justice.”

In July 1997, the Calgary and Edmonton Hells Angels were finally established when they absorbed twenty-three Grim Reapers, becoming Canada’s thirteenth and fourteenth chapters. Weldon became a member of the elite Nomads within the Hells Angels.

See also: Hells Angels, Nomads.

Sieur des Groseilliers: English Hero, French Outlaw – He was born in France in July 1618 and christened Médard Chouart. He became Sieur des Groseilliers after he inherited a patch of family land where there were many gooseberry bushes, or groseilliers.

Like early coureurs de bois (runners of the woods) Étienne Brûlé and Pierre-Esprit Radisson, Groseilliers has had an honoured place in English-Canadian history as a great adventurer and explorer.

He arrived in Canada in 1641, and in 1647 married Hélène Martin, daughter of Abraham Martin, for whom the Plains of Abraham was named. Through his marriage, he became acquainted with fur traders of Acadia, the de la Tours. His wife died soon after the marriage, and he was remarried in 1653 to the half-sister of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, who then was a captive of the Iroquois.

At this time, New France was money-starved, and the wilderness areas of the west offered great promise. Fur-trading saved New France from bankruptcy, even though the state and Jesuits disapproved of its residents moving to live with the Indians.

Groseilliers was jailed with Radisson (who had been freed by the Iroquois in 1653) and most of his furs were confiscated in the summer of 1660, when he returned from the longest and most successful canoe journey of any white person of that time, a journey that had taken him to present-day Wisconsin and Minnesota. He sought redress from Paris, but was denied, and turned in frustration to the English as sponsors.

In yet another reversal of loyalties, he and Radisson went back to the French in 1675. They received pardons, and then helped organize a French rival to the English Hudson’s Bay Company, known as the Compagnie du Nord.

He and Radisson were schemers of the highest order and, in 1681, Radisson returned to London to work as a spy for the powerful French smuggler Charles de la Chenaye.

Toward the end of his life, Groseilliers faded into obscurity, and alternate theories have him dying in the community Hudson Bay or, more likely, in New France as late as 1697.

See also: Coureurs de Bois, Pierre-Esprit Radisson.

Guess, Gillian: Fresher Evidence – When the attractive blonde had an affair in 1995, the fireworks weren’t restricted to the bedroom. Her lover, Peter Gill, was ten years her junior, and on trial for a gangland murder.

Making things even hotter was the fact that Guess worked with the North Vancouver RCMP counselling crime victims, and she was on the jury that was hearing Gill’s case at the same time she was secretly sleeping with him.

Her clandestine trysts with Gill became tabloid fodder, and the first-time offender drew an eighteen-month sentence – of which she served three months – despite having no previous brushes with the law. Meanwhile, Gill walked on the murder charges. With that, Guess became the first juror in North America and the Commonwealth convicted of wilfully attempting to obstruct justice. Her couplings with the gangster were even the subject of a Harvard Law School Web site.

Guess did nothing to escape the spotlight, even setting up a Web site of her own that reproduced articles about her, coupled with her own musings. The affair started, she said, because of mutual curiosity. Then, as things advanced, Guess explained, she feared Gill and felt trapped. He encouraged her to convict two of his co-accused, including his brother-in-law, Bindy Johal, who was gunned down in a nightclub three years later.

Gillian Guess (Alex Waterhouse-Hayward, for Saturday Night, January 27, 2000)

The sordid affair reached the B.C. Court of Appeal, where five justices studied a photograph by Vancouver photographer Alex Waterhouse-Hayward, which showed Guess luxuriating in a bathtub, showing off a naked leg displaying an electronic-monitoring ankle bracelet. The photo was introduced by defence lawyer Ian Donaldson to show Guess sought media attention, despite her earlier protests to the contrary. “This is even fresher evidence,” Justice George Cumming joked when he saw it.

See also: Peter Gill, Bhupinder “Bindy” Johal.

Gyakuzuki – See Project Gyakuzuki.