1 The string quartet and society

We are ‘living in a bad time for practising the intimate, introspective art of the string quartet’.1 So writes a UK broadsheet journalist at the dawn of the twenty-first century. He is talking, be it said at once, about the difficulties of making a living solely as a professional chamber ensemble that plays the classical repertoire and, though despairing of dwindling public interest, and of string quartets selling out to razzmatazz and pop, he ends with an optimistic assessment of fresh ideas for drawing in new audiences. Be that as it may, his initial, nostalgic message is clear: it was not always thus. Indeed, times have changed as far as the string quartet’s relationship with society is concerned: and like other types of music, the string quartet has a social and cultural history, well worth exploring.2

This chapter attempts to draw out some of the central threads in that history, by presenting an outline of the changing social function of the string quartet, along with fluctuations in cultural attitudes towards it, from mid-eighteenth-century central-European beginnings right up to the present. The main theme is the relationship between performers and repertoire on the one hand and audiences or ‘society’ on the other – at root demonstrating a shift from participation to listening. But there is counterpoint, too, not least in the intimacy of the quartet genre and in how, as the very epitome of the chamber music ideal, it has responded to the problems and challenges that external factors have brought.3

Music of friends

The story of the string quartet begins in the second half of the eighteenth century, with the newly emerging body of works composed for two violins, viola and cello – sometimes called ‘serenade’, sometimes ‘divertimento’, sometimes ‘quartetto’ (a consistent nomenclature had yet to crystallise) – and intended as ‘real’ chamber music: that is, music to be performed for its own sake and the enjoyment of its players, in private residences (usually in rooms of limited size), perhaps in the presence of a few listeners, perhaps not. Written by composers such as Vanhal, Gossec, Boccherini, Haydn and Mozart, these works followed on in a long line of music for domestic recreation that stretched back to the madrigals of the fifteenth century and earlier.4 However, the special timbres and subtly variegated hues created by music spread among four string instruments gave the string quartet a particular purity that was a new departure for chamber music (English viol fantasias excepted); and this may well have marked out the quartet as something different in the minds of its players. At any rate, the quartet edged out the trio sonata as principal instrumental ensemble in the home relatively quickly: a less surprising change than we might at first imagine, given that this was an age when the contemporary and new were constantly sought after.

Quartet composition took off in a number of European centres, but there was by no means one homogeneous idiom, and works embodied differing levels of thematic development, equality of part-writing and concentration of expression – the qualities that later became the touchstone of the Classical quartet style. As it happened, those qualities were first enshrined in Vienna by Haydn and Mozart, who brought the quartet to a notable peak of artistic maturity around the 1780s. Sets of works such as Haydn’s Op. 33 or Mozart’s six quartets dedicated to Haydn produced, albeit unintentionally, the prototype against which the quartet repertoire was for a long time thereafter to be measured and even modelled, setting the genre apart from most other types of contemporary chamber music. This was the quintessential ‘music of friends’,5 an intimate and tightly constructed dialogue among equals, at once subtle and serious, challenging to play, and with direct appeal to the earnest enthusiast. ‘Four rational people conversing’ was how Goethe would later see it.6

Wherever quartet-playing flourished in eighteenth-century Europe (for example in Austria, Germany, Britain, France and Russia), it was typically the province of serious music-lovers among the wealthy, leisured classes – the aristocracy and emerging bourgeoisie. Furthermore, in light of the social conventions then governing the playing of instruments in polite society, it was executed exclusively by men.7 Women played the keyboard or the harp or sang for private recreation, but were never to be seen with limbs in ungainly disarray playing violins, violas or cellos. That, and the serious business of quartet music, was left to cognoscenti husbands, sons, brothers and fathers – though women were surely allowed to listen in, when the presence of a small audience was deemed appropriate.8

Reconstructing this musical world is not easy. The essentially private nature of quartet-playing renders documentation scanty, suggesting a less extensive activity than was almost certainly the case; but occasional accounts in diaries, letters and the like enable some glimpses to be caught. Writing from Vienna in 1785 Leopold Mozart recounted one gathering of five people (himself, his son, Haydn, and ‘the two Barons Tinti’), at which four of them played three of Wolfgang’s new quartets (K. 458, 464, 465); in England, a few years later, the gentleman composer John Marsh noted that he and his brother William had been ‘to Mr Toghill’s to meet Maj’r Goodenough & play some of Haydn’s 2 first setts of quartettos [?Opp. 1 and 2] w’ch the Major play’d remarkably well’ in spite of his quiet tone production.9 Much of this sort of testimony blurs distinctions between ad hoc music-making by the players alone and organised play-throughs at which listeners were present, suggesting that many quartet parties doubled as informal, private concerts, or at least that gatherings with audiences were the ones most frequently documented. Take, for example, the memoir of the Muscovite Prince I. M. Dolgoruky, writing about chamber music at his home in 1791:

Every week during Lent we had small concerts: Prince Khilkov, Prince Shakhovskoy, Novosiltsev, Tit [? composer S. N. Titov], passionate lovers of music and excellent exponents themselves, came over to us to play quartets.10

Likewise, the account by the singer Michael Kelly of a Viennese gathering at which quartets were played by Haydn, Dittersdorf (violins), Mozart (viola) and Vanhal (cello) and at which Paisiello and the poet Casti were, like him, among the audience. His oft-quoted remarks include the apt observation of Viennese quartet culture (‘a greater treat or a more remarkable one cannot be imagined’), and remind us that the musical rewards of quartet-playing made professional musicians – almost invariably from lower social orders than the leisured classes – some of the most avid participants and enthusiasts.11

Key to the spread of quartet-playing in the late eighteenth century was the publication of parts, usually in Vienna, Paris or London, and dissemination to a range of urban centres. Although the market, in comparison with that for piano music, songs and other popular domestic genres, was relatively limited in size, and the music costly, there were enough wealthy Kenner und Liebhaber around to stoke a reasonable demand. According to one scholar’s calculation, several thousand quartets by about 200 composers (both French and foreign) were published in Paris between 1770 and 1800.12 Some of the repertoire – particularly Viennese quartets, namely Haydn’s, Mozart’s, and Beethoven’s Op. 18 – was tough for any but the most highly skilled amateurs to get through, and while such players certainly existed (Wilhelm II, dedicatee of Mozart’s three Prussian quartets, is a good example), many were surely less accomplished and may have sought more manageable fare. A number of French works, designated quatuors concertants,13 by composers such as Vachon and Bréval were elegant, easy-to-play pieces which, lacking tightly wrought musical arguments à la Viennoise, boasted a democratic, if simple, sharing of material: aping French salon conversation, as another commentator has argued.14 Other repertoire for quartet players included arrangements of large-scale works such as symphonies, operas and oratorios: these were a popular way of recalling and recreating pieces from the public arena. Operatic medleys, known as quatuors d’airs connus, were also favourites with French publishers and amateurs.15

Figure 1.1 Quartet evening at the home of Alexis Fedorovich L’vov, c. 1845

Several amateur ensembles probably lacked skilled players, though wealthy and influential patrons could always buy their way out of difficulty. George IV, when Prince of Wales, delighted in playing the cello in quartets, alongside top London performers, in private.16 In Vienna, c. 1795 Prince Lichnowsky hired Ignaz Schuppanzigh (later to become the great player of Beethoven’s quartets) and others to entertain him and guests on a weekly basis.17 On the other hand, many chamber music lovers surely relished laborious repeated attempts at a repertoire; and although the early nineteenth century was to see public concerts open up to the quartet, the practice of domestic quartet-playing persisted, with special keenness in German-speaking lands, where Hausmusik would be an important part of life for the professional and business classes for decades to come.

Figure 1.2 Quartet performing at the Monday Popular Concerts in St James’s Hall, London; from an engraving in the Illustrated London News (2 March 1872). The players are Madame Norman-Neruda (violin 1), Louis Ries (violin 2), Ludwig Straus (viola) and Alfredo Piatti (cello)

Into the concert hall

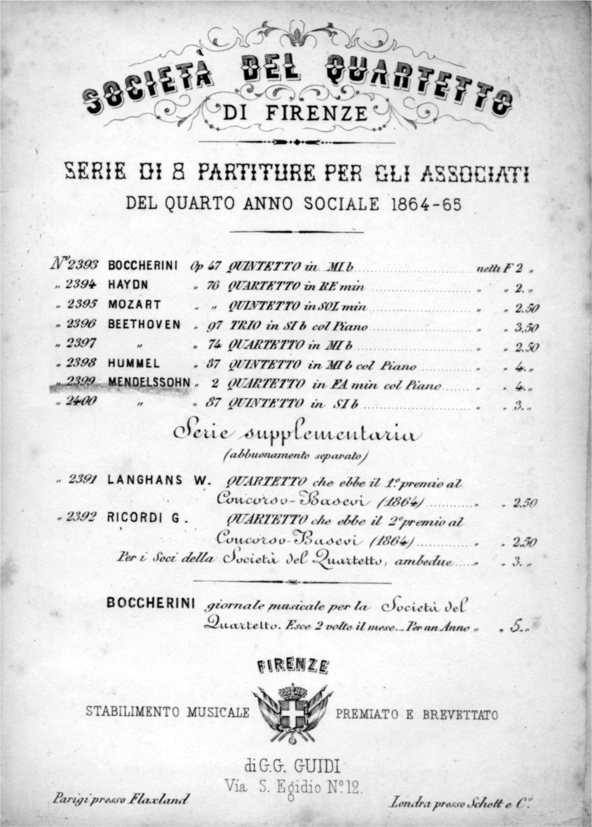

As commercial concert-giving advanced in many European centres in the first half of the nineteenth century, chamber music and particularly string quartets became a familiar presence in the concert hall. A few precedents existed, in that quartets had typically featured in miscellaneous orchestral and vocal concerts, especially in England – Haydn famously writing in extrovert style for 1790s London in his Opp. 71 and 74; and around the turn of the eighteenth century a burgeoning, organised culture of private salon concerts, at which quartets were performed, had emerged in cities such as Vienna and Paris.18 But it was in the early nineteenth century that a new type of ‘public’ concert, devoted exclusively to chamber music – very occasionally to string quartets alone – was born, with audiences formed initially around groups of enthusiastic amateur practitioners, and performances safeguarded financially by subscription lists. New initiatives included Schuppanzigh’s quartet concerts at Count Razumovsky’s palace in Vienna (begun in 1804–5), Karl Möser’s quartet evenings in Berlin (in 1813–14) and Pierre Baillot’s Séances de Quatuors et de Quintettes in Paris (in 1814). Other developments followed, with varying lifespans. In London a rash of innovations broke out in the 1835–6 season (the Concerti da Camera, the Quartett Concerts, the Classical Chamber Concerts) and, later, institutions such as John Ella’s Musical Union (1845–81; see Fig. 3.1, p. 43 below) and Chappell’s Popular Concerts (1859–1902) came into being. Meanwhile, Vienna had its Musikalische Abendunterhaltungen under the auspices of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (1818–29; 1831–40) and Joseph Hellmesberger’s quartet concerts (established in 1849); and Paris witnessed a flurry of series such as those set up by Alard and Chevillard (1837–48), the Tilmant brothers (1833–49) and the Dancla brothers (1838–70), followed by the notable Société Alard et Franchomme (1847–70) and Société des Quatuors Armingaud et Jacquard (1856–68). As the century unfolded, concert life continued to grow and diversify, with many quartet performances, in most European centres of population. New audiences were drawn in; concert-giving spread into countries such as Spain and Italy where operatic traditions had previously held sway; and first inroads were made into the USA. Among several notable newcomers were the Mason and Thomas Chamber Music Soirées in New York (1855–68), the Società del Quartetto in Florence (established 1861), the similarly named organisation in Milan (1864; Boito was a supporter), the Kammermusikforening in Copenhagen (1868) and the Kammermusikverein in Prague (1876).19

Figure 1.3 Title-page for the series of pocket scores specially published in Florence by G. G. Guidi for the Società del Quartetto di Firenze’s concerts of 1864–5 [actual size 10 cm × 14.3 cm]

Chamber music succeeded in the concert hall partly because of the low costs and ease of rehearsal (in contrast to full orchestra concerts) that were involved, but it also entailed some aesthetic contradictions, especially for the string quartet. Formal halls, reverberant acoustics and sizeable audiences (the last an economic necessity for financial well-being) were decidedly at odds with the inwardness of quartet playing and the intricate details that Classical composers had intended to be heard; and public performance seemed the very antithesis of the idiom. Recognising this, some concert promoters in London made adaptations to the layout of the concert hall and seating arrangements in the hope of creating an aura of intimacy: Ella, apparently taking his cue from Prince Czartoryski’s private quartet concerts in Vienna, placed the performers in the centre of the hall and had the audience sit around them, drawing listeners into the music and the music-making.20 Performers learned to project the sound out rather than in, and by the turn of the century some purpose-built chamber music halls (Bösendorfer-Saal, Vienna, 1872; Bechstein Hall, London, 1901; both built by prominent piano firms) were offering more intimate surroundings. Composers reacted to the new environment too. Richly resonant writing, thicker textures and bold gestures – vocabulary for larger spaces – were fused with the conventions of tightly knit structure and concentration of expression in many a nineteenth-century quartet; and professional players rather than amateurs became the intended executants, with technical demands increasing accordingly, from Beethoven’s Op. 59 (written for Schuppanzigh’s ensemble) right through to Tchaikovsky’s and Smetana’s quartets.21 By comparison, the domestic repertoire was only occasionally replenished – George Onslow was a notable exponent.

In many cities, quartets were played by local string players, usually the leading orchestral musicians in the area, who formed regular concert line-ups and gathered kudos for the musical advantages – unanimity of ensemble and phrasing, the blending of tone – this brought.22 But visiting top-class performers, especially first violinists, could usually offer more, filling halls with listeners as well as sound; and at some concerts, particularly in the second half of the century, ‘star’ violinists were habitually slotted above three local players, rewarding box office and connoisseurs alike, though sometimes earning critical censure for loose ensemble. This practice was particularly common in London, concert marketplace extraordinaire, whose visitors included Vieuxtemps, Auer and Sarasate. There were also a few touring foursomes, often brothers, usually Germans. The Moralts (1800–?; 1830–40), the Müllers (two generations: 1831–55; 1855–73), and the Herrmanns (none of whom were brothers or called ‘Herrmann’; 1824–30) all travelled Europe, capitalising on kinship as much as musicianship, and foreshadowing, in some respects, the ‘professional’ quartets that began to flourish around the turn of the nineteenth century. These included Joachim’s Berlin-based quartet; the Brodsky Quartet in Manchester; and two touring ensembles: the Czech Quartet in Europe and the Kneisel Quartet in America.

Throughout the century, the shape and content of concert programmes was subject to a good deal of local variation. In Paris, Baillot’s Séances (which lasted till 1840) comprised four or five string quartets or quintets – typically a range of works by Haydn, Mozart, Boccherini and Beethoven – topped off by a showy violin solo with piano accompaniment. Most concerts in London in the 1830s and 1840s, by comparison, were longer and their contents more mixed: chamber music with piano was virtually indispensable (the Beethoven piano trios and Schumann piano quartet and quintet were much performed), though string quartets occupied an important place (initially a broad range of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn; later additions included Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Dvo ák) and the instrumental items were invariably interspersed by songs.23 Concerts of quartets alone, complete with ‘logical’, or chronological, programming, were something of a rarity until the early to mid twentieth century. Even then, adding a pianist or other instrumentalist(s) for quintets and so on was a common way of introducing contrast and broadening appeal.

ák) and the instrumental items were invariably interspersed by songs.23 Concerts of quartets alone, complete with ‘logical’, or chronological, programming, were something of a rarity until the early to mid twentieth century. Even then, adding a pianist or other instrumentalist(s) for quintets and so on was a common way of introducing contrast and broadening appeal.

More significantly, chamber music’s arrival in the concert hall coincided with, and reinforced, the widespread preservation and enshrinement of the Viennese classics in the repertoire. In practice this meant that, from the outset, string quartets were at the heart of things, most especially the last ten works by Mozart, Haydn’s Opp. 76 and 77 (and a few others, too) and Beethoven’s Opp. 18, 59 and 74. While modern quartets were added to the ‘favourites’ list gradually – e.g. Mendelssohn’s Opp. 12 and 44, Schubert’s A minor and D minor, and some Brahms, Dvo ák and Tchaikovsky – the old remained, anchoring the repertoire around a body of works that were fast taking on special status as exemplars of high musical art. This in itself was a ‘new’ thing. The Beethoven quartets represented the pinnacle of achievement and seriousness, and rapidly became central and canonic at all times and in all places; championing of the late quartets (occasionally broached but not yet fully assimilated) was undertaken by such institutions as the Beethoven Quartett Society (1845–52; London) and the Société des Derniers Quatuors (established in Paris, 1852). Meanwhile, pieces for other chamber music combinations – Mozart’s G minor and C major string quintets, Beethoven’s ‘Archduke’ piano trio, Schumann’s piano quintet – became embedded in the repertoire too.

ák and Tchaikovsky – the old remained, anchoring the repertoire around a body of works that were fast taking on special status as exemplars of high musical art. This in itself was a ‘new’ thing. The Beethoven quartets represented the pinnacle of achievement and seriousness, and rapidly became central and canonic at all times and in all places; championing of the late quartets (occasionally broached but not yet fully assimilated) was undertaken by such institutions as the Beethoven Quartett Society (1845–52; London) and the Société des Derniers Quatuors (established in Paris, 1852). Meanwhile, pieces for other chamber music combinations – Mozart’s G minor and C major string quintets, Beethoven’s ‘Archduke’ piano trio, Schumann’s piano quintet – became embedded in the repertoire too.

A diet of string quartets, even when mixed with piano trios and so on, was for many listeners something of an acquired taste, and palates almost always benefited from a little education. This was particularly the case for initiates to chamber music, but it was also true for those who were familiar with some quartets from their own domestic music-making, given that perceptions gained from playing, as opposed to listening, were very likely to differ; that new works were beyond many amateurs’ performance capabilities anyhow; and that appreciation could always be deepened. Insightful critics, writing in the ever-growing print media, filled some of this need for enlightenment, at the same time celebrating the genre’s inherent seriousness. Equally, at some concerts (starting with those in England) informative programme notes were provided, with a view to explaining formal and tonal structures and unlocking expressive content.24 Musical literacy was taken for granted – these were the glory days of the pianoforte – and listeners were expected to work hard at gaining familiarity with the music in whatever way they could, including self-improvement at home. Miniature scores were one route to this sort of appreciation (they were on sale as early as the middle of the century); piano transcriptions, often à quatre mains, were another.25 Domestic quartet-playing may have contributed to the process, especially in musical Germany, but evidence for the true extent of such practices is lacking. Nevertheless, the classic pieces for home erudition were the staple Viennese quartets – clearly essential reading for anyone aspiring to appreciate chamber music.

Back in the eighteenth century, a love of string quartets had been largely limited to two groups: interested amateurs with sufficient wealth to play them, or status to attend select, private renditions; and musicians and their families. In the nineteenth, the advent of chamber music concerts, often at modest prices, allowed the treasures of the quartet repertoire to be opened up to many who would hitherto have been excluded. Notably also, women became a significant part of the audience.26 Wealthy connoisseurs remained keen advocates and several concert societies were supported by well-heeled, even aristocratic, listeners, while at the other end of the scale the doors were opened to aspirants to high culture and respectability among the lower orders. In Vienna, August Duisberg’s quartet mounted low-cost subscription concerts on Sunday afternoons, aimed at lower middle- and working-class people; in London, there were the philanthropic and morally worthy South Place Ethical Society’s Sunday chamber concerts (1887–), to which admission was free.27

Enter technology

In the early twentieth century gramophone records and, later, broadcasting created a new environment for listening to string quartets, taking the music back into people’s homes for private consumption. Anyone with sufficient interest (and initially, for records, spending power) could now experience what was generally deemed to be the finest art music, finely played, again and again in his/her own home. Although there were, by the mid-1930s, many types of music for gramophone listeners to choose from, chamber music, and ipso facto string quartets, on record always had the in-built advantage of verisimilitude, with which opera and orchestral music could simply not compete. To paraphrase Compton Mackenzie, founding editor of Gramophone magazine, it was tantamount to having one’s own private string quartet and would likely become a real substitute. Of course, the technology was far from perfect, as Mackenzie freely admitted – ‘the winding of it [the gramophone], the hiss of the needle, the interruptions caused by changing discs’ amounted to a ‘detestable handicap’, and there was the loss of the live ‘beauty of sound in motion’ – but the ‘78’ record nevertheless offered listeners to quartets the opportunity of hearing nuances and intricacies often missed in the concert hall, and of getting to know the repertoire through repeated sitting-room encounters. Mackenzie, for one, was in no doubt that for string quartets, the intensity of gramophone listening was preferable to concert-going, and in Walter Willson Cobbett’s encyclopedia of chamber music (first issued in 1929) he proselytised accordingly.28

Even in the early days of acoustic recording (up to 1927) the string quartet had reproduced well, giving it a head start in the building of a repertoire. And with electrical recording, many ‘standard’ quartets (or at least movements from them) – some sixty-odd works from Haydn to Debussy – swiftly became available.29 The number of professional string quartets with relatively permanent personnel was beginning to increase significantly, along with standards of playing, and groups such as the Rosé, Flonzaley, Léner and London quartets recorded several works. In the 1930s, Europe (in particular London) became the focus of activity; many notable recordings were made by the Busch, Léner and Budapest quartets. Records, however, were expensive, their bulk and fragility adding heavy distribution costs. Special interest groups were therefore encouraged to guarantee risky ventures by subscription: the Haydn Quartet ‘Society’, for example, was HMV’s device for marketing the Pro Arte’s cycle of twenty-nine of the quartets. Whether by luck or by judgement, the record companies were making significant investments in much of the chamber repertoire; the range of music explored was considerably enlarged, reinforcing hierarchies of works (including, of course, quartets) and artists in the process.30 And like concert-givers before them, record companies found that ensembles were relatively cheap to hire, and usually came pre-rehearsed. Besides, the music itself would endure.

Figure 1.4 The Budapest Quartet playing to the United States Army Air Forces Technical School in Colorado during World War II

From the late 1920s onwards, broadcasting, of recordings or studio concerts, gave string quartets access to an immense and broadly based audience. Government-funded stations such as the BBC carried a good deal of carefully chosen serious music, including quartets, on mainstream channels.31 The medium could also, as in the case of the BBC’s Light Programme ‘Music in Miniature’ – a half-hour compilation of single, appealing movements from chamber works, put out during evening slots, 1945–51 – do a little evangelising. By this time, a sizeable music appreciation literature based around recordings of what were considered the ‘classic’ quartets had grown up, and much wisdom and elucidation by Percy Scholes and others awaited any neophytes.32

The long-playing record arrived at the end of the 1940s, removing the constraints of the ‘78’ format and reducing costs and, ultimately, prices. During the 1950s and 1960s the market expanded to become truly international, Japan, the USA and Australasia being significant growth areas. As new labels appeared and ensembles jostled for contracts, the repertoire also took off. Enthusiasts could now purchase all the quartets of Haydn, Mozart and Schubert (Beethoven had long stood alone in the catalogues in this respect), explore a range of nineteenth-century repertoire (and additionally many works for enlarged ensembles – the Brahms string quintets and sextets, a range of piano quartets and quintets, and so on) or discover modern newcomers (most crucially, the six Bartók quartets). Multiple recordings of the same piece could be compared, with help from a new industry of published and broadcast journalism.33 From the players’ perspective, there were three principal sources of employment: recording, broadcasting and ‘live’ concerts – and a lifetime’s worth of music too.

The aftermath of World War II saw the number of professional ensembles expand further, and with unprecedented vigour. This was the period when quartets such as the Amadeus, the Fine Arts, the Juilliard, the Hollywood and the Quartetto Italiano came forward. Many groups, particularly in the USA, were formed from the pool of top-quality string-playing Jewish refugees who had fled Nazi Europe in the 1930s. These were people with a strong, vibrant tradition of quartet-playing, and some brought extraordinary talent and much experience. The Budapest and Amadeus quartets, to name just two, had members from such a background.34 A shared training was also fairly common and helped groups create distinctive stylistic and sonorous identities: the members of the Pro Arte were all former students of the Brussels Conservatoire; those of the Léner were from the Hungarian Royal Academy of Music; and the upper Austro-German strings of the Amadeus had all learned with Max Rostal.

Contrary to what Compton Mackenzie had believed or even hoped, chamber music concerts did not fade out in retreat from technological innovations. Concert life continued throughout the twentieth century, though in Europe it was twice ruptured by world wars. Social change made its mark, too. In the decade before World War I, professional quartets with women players – some, famously, staffed by women alone (e.g. the Norah Clench and Langley–Mukle ensembles) – had come into existence in England. This reflected economic realities as well as changing social attitudes: for although gender taboos on string instruments had been broken and advanced training opportunities increased during the late nineteenth century, orchestral chairs were in the pre-war decade still largely occupied by men. The self-regulating nature of string quartets enabled many capable female ensembles to enjoy prominence into the 1930s. Thereafter these groups fell away, though a few women took up places in reputable quartets: it would nevertheless be some decades more before quartets with significant international reputations would regularly contain or comprise women.35

By the 1960s the quartet recital had become an established concert type worldwide, with a piece for larger or mixed ensemble often prominent in a programme. Air travel, a world market and punishing schedules became commonplace for some groups. Chamber music societies, which were growing aplenty, booked ensembles, as did American universities – the so-called campus circuit – and specialist summer festivals. Wide availability of records and radio broadcasts meant that an ensemble’s reputation literally could go before it, securing ticket sell-outs in countries where it had never given a live performance.36 The chamber music scene in both the USA and Britain was particularly strong in the decades after World War II, audiences having benefited from a sizeable pre-war influx of music-lovers with central European cultural values, which regarded the string quartet as the highest of high musical art.37

Beethoven remained at the apex of the quartet repertoire, in concert hall and on disc, with Brahms and later Bartók becoming rightful heirs. As a genre, the quartet retained its hold over composers as a repository for their most intimate thoughts and close working-out, and a steady supply of fresh works came forth, often tailored to particular ensembles. Shostakovich composed many works for the Beethoven Quartet, Bartók’s Fourth was written for the Kolisch, Britten’s Third for the Amadeus, Tippett’s Fifth for the Lindsay. Several groups proved keen to explore new quartets alongside the standard repertoire, and a few developed close working relationships with composers.38 Technical standards were reaching unprecedented levels, and composers responded, making acute, often highly imaginative, demands of the players.

Private patrons also stimulated quartet composition and performance, most notably in the early decades of the century. In Britain, the dictionary-making ex-businessman Cobbett supported chamber music in several ways. His most celebrated act was the establishment in 1905 of a number of prizes, including one for ‘phantasy’ chamber works (inspired by Elizabethan viol fantasias), which gave rise to a discrete repertoire of English chamber music, including the phantasy quartets of Hurlestone and Howells.39 The USA had the benefactress Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, herself the winner of one of the Cobbett Medals for services to the art. Among her many grand gestures were the patronage of the Berkshire Festivals of Chamber Music, 1917–24; the establishment of a trust fund at the Library of Congress in Washington in 1925, principally to fund concerts and award composition prizes for new works; and the sponsorship of the library’s Coolidge Auditorium, specially designed for chamber music at a cost of more than $90,000.40 Also noteworthy for her munificence and imagination was Gertrude Clarke Whittall, who donated her five Stradivarius instruments to the Library of Congress and came up with the idea for a quartet residency there, tied to performances on the Strads, in 1938.41 The Budapest Quartet was the first incumbent.

In Europe, international festivals, including those at Donaueschingen and Baden-Baden, and a series organised by the International Society for Contemporary Music, played their part in supporting quartet composition in the inter-war years. Later (1950s and 1960s onwards), universities in the UK and USA instituted residencies for string quartets, providing groups with valuable subventions and environments for artistic renewal. Around the same time summer schools at Dartington and Prussia Cove (UK) and the Marlboro’ Festival (USA) created special training grounds, at which emerging student quartets could learn from veteran chamber musicians such as Sándor Végh and Pablo Casals. Quartet writing continued to be encouraged through the prevalence of chamber media in international composition competitions, the coexistence of composer and quartet residencies in universities, and commissioning programmes, for instance the one established by Chamber Music America (1983).

Shifting cultural values

By the 1970s it looked as if, in the space of a little more than two centuries, the quartet had secured an audience which, though smaller than most listening publics, was far wider than eighteenth-century musicians and nineteenth-century concert-goers would have believed possible. A core repertoire had also been created, preserved and later extended, and had taken on a seemingly unassailable canonic position. There had, admittedly, been a transformation in the nature of string quartet consumption, as the activity changed from one based around participation to one largely constituted of listening and, in the cases of more earnest audiences, knowledgeable appreciation; yet, in spite of occasional performances in large venues and new works that challenged the genre with theatricality and other heterodoxies, the vital ingredients of the quartet ‘experience’ typically remained intimacy and inwardness.

But change was again imminent. During the century’s last two decades, the certainties and values that had for so long been attached to classical music underwent fundamental reassessment, affecting the string quartet as much as any genre. Hierarchies of taste based on value and authoritative judgements came into question, relativism became widely expounded, the dominance of the musical ‘canon’ was challenged, and quartets that had been gathering dust were recovered and rehabilitated.42 The recorded repertoire, in particular, broadened dramatically, and niche labels for unfamiliar works became common. Re-mastered recordings on CD opened up the string quartet’s performance history for all to hear, but the idea that there was a set of ‘gold standard’ string quartets that the music-lover ought to get to know was fast becoming a thing of the past.

Meantime, popular and world musics staked their claim to the serious consideration that classical repertoires had always enjoyed. There were creative gains here, as cross-fertilisation took place. The albums and activities of the Kronos Quartet, which plays works by composers emanating from non-European cultures and juxtaposes different styles in pursuit of extra-musical connections and new types of insight, are a case in point and have been followed by groups such as the new Brodskys and the Soweto String Quartet. But set against this has been a seeping away of widespread serious interest in classical music. (The popularisation of a few orchestral or operatic ‘classics’ – admittedly a sizeable phenomenon – is something else, often treating classical music as material for relaxation, rather than for stimulus and engagement.) The string quartet, in particular, has become tarred with the brush of elitism, on account of its inherent cerebrality as well as its historical associations with wealth and middle-class consumption (Adorno, it should be recalled, famously discussed chamber music’s ‘bourgeois’ identity).43 It is not surprising, then, that imaginative, accessible packaging of both performers and music is a major concern for agents and publicists, and that techniques for attracting new audiences in the first place, and engaging them thereafter, are constantly being tried, some with notable success. The education of newcomers has been a recurring theme in this essay, but given the climate outlined above – not to mention the essence of the quartet genre, conventionally understood, as ‘musicians’ music’, and the fact that widespread familiarity with musical notation has disappeared during the century – the challenge has at no time been greater than at the present. And since the prevailing image is ‘highbrow and elitist’, a live string quartet has become an almost obligatory chic trimming for wedding services and receptions – symbol of high culture and social refinement for consumer-driven ceremonial. The musical content, it should be noted, typically centres around arrangements of popular instrumental classics and jazz and show tunes.

Amidst such cultural change and uncertainty, serious lovers of music continue to support their favourite ensembles and repertoires, and to taste new works, different styles of playing and débutant groups. The choice is great: quartets range from those playing only highly contemporary works (e.g. Arditti Quartet) to those making a virtue out of historical awareness and period performance (Salomon, Quatuor Mosaïques), with many occupying the central, ‘traditional’ repertoire, or exploring curious backwaters. Women, it may be observed, have become an unremarked presence in professional quartets; but making a successful livelihood is tough for all, and winning an international competition, such as the one founded in Banff (1983), can launch an ensemble career. On the domestic front, quartet-playing for its own sake is still pursued by professional musicians seeking recreation and by highly-trained ‘amateur’ string players, the latter presumably forming an important slice of the quartet-listening public, able to connect with performances in the concert hall in uniquely privileged ways. The music of friends still has its friends.