6 Historical awareness in quartet performance

String quartet performance might at first seem an unpromising area for the practice of historical awareness.1 After all, there is no mystery about the instruments required and the musical texts are so explicit that there can be little room for radical re-interpretation. Yet the huge amount of music written in the first seventy or so years of the string quartet’s existence was played on instruments substantially different from their modernised twentieth-century successors. The Classical repertory from Haydn to Schubert and the even more numerous contributions from their lesser contemporaries were written for instruments and bows whose construction reflected their historical position midway between the late Baroque and the early nineteenth century.2 And although the opportunities to decorate or alter the notes on the page became increasingly rare as the eighteenth century progressed, the manner in which these notes were played was also far removed from conventional twentieth-century practice.

The early quartets

An indication of the historical and stylistic location of the early quartets of the mid eighteenth century is given by the fact that several of their composers also produced collections of trio sonatas, a Baroque form then on its last legs. The variety in this early quartet repertory is reflected in its range of titles, from ‘quartetto’ to ‘cassatio’. The content of these works ranged from straight fugues through simple sonata forms to light divertimento movements. Two sets stand out. One of the earliest references to a quartet party is in the autobiography of Dittersdorf, where he recalls tackling ‘six new quartets by Richter’.3 Published in London in 1768, but written ten years earlier if Dittersdorf’s memory is to be trusted, these quartets are remarkable for the equality of their part writing and particularly their liberation of the cello from its bass role, over a decade before Haydn’s Op. 20 no. 2. The second set worthy of special notice is Boccherini’s Op. 2, entered in his own catalogue for 1761, when he was eighteen years old. These are the first serious (non-divertimento) quartets that were composed in Vienna. The first, in C minor, has a ferocious last movement and antedates Haydn’s first minor-key quartet (Op. 9 no. 4 in D minor) by seven years.

Haydn settled on ‘Divertimento a quattro’ as the title for his first ten quartets, when he entered them in his personal catalogue and he continued to use this term until 1785 (Op. 42), when he adopted ‘Quartetto’ in its place. The term for Haydn, therefore, is firmly connected with the string quartet proper and does not in itself suggest any other form of performance. One of the arguments put forward to support the use of a double bass in these early works is the incidence of overlapping parts, which result in momentary second inversions. James Webster significantly notes that they recur throughout Haydn’s output and are not restricted to the ten early quartets.4 Regarding the possible use of keyboard continuo, he suggests that continuo practice had been abandoned in Austrian secular chamber music by 1750. Altogether he makes a convincing case for simple quartet performance of these works.

Although Haydn told his Viennese publisher Artaria that he wanted his quartets to be remembered as starting with Op. 9, which dates from about ten years later, these first quartets can already be seen as a part of his life-long exploration of the form. The first movement of Op. 1 no. 3 in D, which was probably his first (the opus numbers and order come from Pleyel’s edition (1801) and are no indication of chronology), is still half in the world of the trio sonata. For much of the time the two violins are in dialogue over the purely harmonic support of the lower parts. The other slow movements are simply dominated by the first violin, whose occasional virtuosity will be developed further in Opp. 9 and 17; however, as Reginald Barrett-Ayres observes, ‘From the first quartet . . . to no. 10 in F (Op. 2 no. 4), Haydn makes some progress towards a real quartet style.’5 The galant idiom of these early quartets is just a step away from the Baroque. Their generally light and pleasant air, short phrases and articulated language hardly make any demands on the instruments or style of performance beyond those of the late Baroque.

One quartet composer, however, Gaetano Pugnani (six quartets, 1763), had a very different playing style, one which, through his pupil Viotti, makes him the grandfather of the modern violin school of the Paris Conservatoire. Pugnani used a bow that was longer and straighter than the norm, and he employed thick strings. His grand bowing manner and powerful tone were recalled by Spohr when he visited Italy in 1816. Spohr wrote: ‘my playing reminds them of the style of their veteran violinists Pugnani and Tartini, whose grand and dignified manner of handling the violin has become wholly lost in Italy’.6 Pugnani’s debut at the Concert Spirituel of 1754 created a sensation. That of Viotti in 1782 was even more fêted and had a more profound influence. Viotti’s playing was characterised by a big full tone in addition to a powerful singing legato and a highly varied bowing technique. It was ‘fiery, bold, pathetic and sublime’.7 This substantially different playing style, notable for its power and legato, cried out for a new model of bow. The design that François Tourte perfected towards the end of the century was associated with Viotti, although, apart from Woldemar’s Grande méthode (1800), where it appears as L’Archet de Viotti with the comment that it is ‘almost solely in use today’ (see Fig. 2.5), little evidence exists of a direct personal connection;8 even so, Viotti’s bow may not have been of quite the full modern length. Complementing the bigger bowing style (arco magno) of Pugnani and Viotti were the extended demands on left-hand technique and fingering.

Fingering

In Haydn’s three sets Opp. 9, 17 and 20 such advances in technique included playing una corda, a technique more often associated with the nineteenth century and particularly Paganini. Una corda indicates playing from bottom to top on one string (usually the G) instead of crossing over to higher strings. These violinistic challenges were probably inspired by the presence of Luigi Tomasini, leader of Haydn’s orchestra and considered by Haydn to be the most expressive player of his quartets. The slow movement of Op. 17 no. 2 could be regarded as an operatic duet between the mezzo soprano (A string) and tenor (G string), in the same category as the overtly operatic slow movements of Op. 9 no. 2, Op. 17 no. 5 and Op. 20 no. 2. However, Haydn’s use of una corda, which appears in all his sets of quartets from Op. 17 onwards, is never merely virtuosic. It is employed for colour, to ensure portamenti, or simply for broad humour, as in the trio of Op. 33 no. 2. This last example, which is very explicitly fingered, is quoted by Baillot, who rather bowdlerises it by reducing the slide to a minimum.9 In all these cases una corda remained for Haydn a special effect, whereas for later writers it became part of a string player’s general technique and style.

Already in 1756 Leopold Mozart recommends playing una corda for equality of tone and a more consistent and singing style.10 Around the turn of the century the theorist and violinist Galeazzi suggests, for expressive passages, never using two strings for music that can be played on one, and avoiding open strings, with their harder sound, for the same reasons.11 Baillot (1835), however, considers the use of una corda as a matter of personal preference; according to him, Viotti almost always played in one position, whereas Rode and Kreutzer often played up and down the string.12 At the turn of the following century Maurice Hayot was untypical of his time in that he avoided position changes and portamenti and played wherever possible in the first position. Flesch was particularly impressed by his performances of Mozart quartets.13 But more typical of nineteenth-century practice were the fingerings of Ferdinand David and Andreas Moser, which produce frequent and casual portamenti and, by generally avoiding second and fourth positions, involve large movements of the hand. Leaving aside the personal preferences of particular players, it seems that una corda playing and its associated portamenti were treated as special effects in the late eighteenth century but became an integral part of violin technique in the nineteenth.

With the increasing use of portamento, a variety of portamento types became distinguishable, of which some were considered more acceptable than others; and, as with vibrato, there were always those who condemned its overuse in general. The most practised model was that in which, when sliding between two notes, the slide is made with the starting finger; sliding with the finger of arrival was generally disapproved of, as was gratuitous sliding when descending to an open string. Slides of different speeds, leaping, anticipating, changing finger on the same note, sliding to a harmonic, and various personalised combinations of all these, accumulated through the nineteenth century. Andreas Moser in 1905 still does not recognise the slide with the arriving finger and advocates restraint; Carl Flesch recognises both kinds, but advises discretion in the use of the latter, and discrimination in the use of either.14

Bowing

The comparison of the string quartet with a stimulating conversation between four intelligent people is particularly apt in the case of Haydn.15 Such conversation took on a weightier and more intense tone from Op. 9 onwards. Sforzando markings appear in increasing numbers and are often associated with disruptive syncopations. These were complemented by cantabile, sostenuto and tenuto markings, all calling for a more ‘muscular’ bowing style, which in turn demanded the newer models of bow (Cramer and Viotti), with their heavier heads and wider ribbon of hair.

The need for the ‘modernised’ violins and bows is even stronger in the case of Mozart’s mature quartets. His early quartets began their evolutionary journey, as had Haydn’s, from a trio-sonata-like movement – the Adagio which opens K. 80. When, after a gap of nine years, Mozart wrote the six quartets dedicated to Haydn, he adopted a full-blown operatic style, whose long singing lines simply cannot be adequately played without the longer bows and the more powerful instruments, built or modified according to the latest developments of the time. The cantabile character of Mozart’s quartets is part of his personal style, but emulation of the human voice, in both its singing and speaking capacities, has been standard advice to violinists from Telemann to Galamian. Now, on the threshold of the nineteenth century, the scale of that voice was bigger. Although reference is still made to speech and punctuation in writings of the time and continued to be so throughout the next century, it is the singing element which is in the ascendant. Even Haydn, whose language is most speech-like, stretches it to the limit. The opening bars of the Adagio of his penultimate complete quartet (Op. 77 no. 1) have a breadth of line that overrides the bar lines, and a sostenuto indicated by slurs that can no longer be simply equated with bowing; they are, as László Somfai suggests, indications of phrasing in the nineteenth-century sense.

An even more seamless effect seems to be intended in the variations movement of the ‘Emperor’ Quartet (Op. 76 no. 3), and in the Trio of Op. 77 no. 2, where their purpose appears to be to conceal any break of articulation and to bypass the bar lines (Ex. 6.1). A similar feeling of the music bursting out of its metrical jacket is present from the beginning of Mozart’s first mature quartet (K. 387). The restless effect of the frequently changing dynamic markings is compounded by the crescendos at bars 8 and 10 which go against the metrical order and the natural shape of the phrase. The broad approach which this music calls for accords with Mozart’s own preferred playing style. The grand and singing bowing of the Italians was admired by his father Leopold, who advises playing ‘with earnestness and manliness’; this respect for legato playing was shared by the son, whose quartets abound in slurs that are often too long to be bowing marks.16

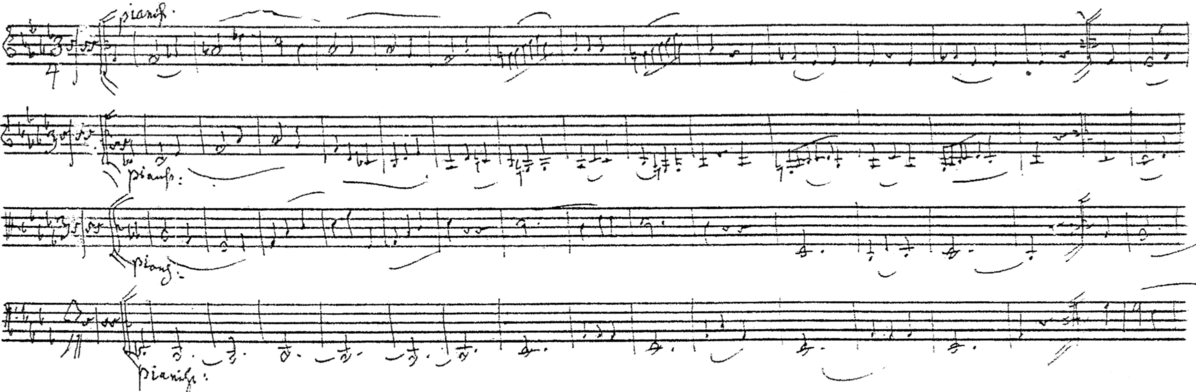

Example 6.1 Facsimile of the autograph Ms. of Haydn’s Quartet in F major Op. 77 no. 2, iii (Trio)

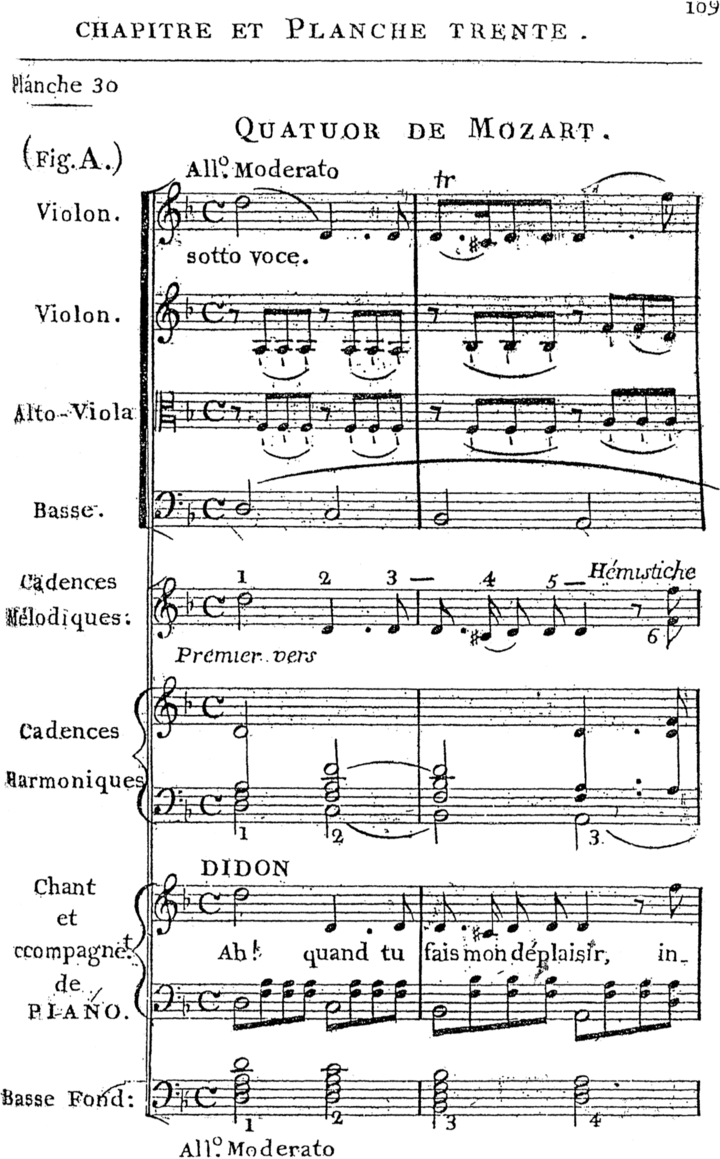

The hierarchical system which these long legato lines override, and which is violated by the offbeat sforzandi and crescendos of the type just mentioned, is described in detail in writings of the time.17 It is a system in which units of all sizes – phrase, bar and beat – are in a state of diminuendo; so the first part of a phrase, bar or beat is by rights stronger than the second. This fundamental order, against which other claims for musical emphasis were pitted, was being proposed until well into the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, a less respectful attitude towards the bar line developed around the turn of the century and the novel ideas of the Belgian theorist Jérôme-Joseph de Momigny were in keeping with this new thinking.18 Momigny related music to the human walking pace and reduced all music to a series of cadences, pairs of notes consisting of an upbeat and a downbeat which were ‘mariées cadençalement’. This marital analogy was carried through to the extent that a phrase which began on a downbeat was considered to start with a note in a state of widowhood. The bar-line between these two notes was, according to Momigny, a sign of union and not of separation. His theories are elaborately illustrated in a ten-stave score of the first movement of Mozart’s D minor Quartet K. 421. This shows the melodic and harmonic cadences, and sets the entire first violin part to Dido’s speech to the departing Aeneas, which he considered to be the best way to express the true feeling of the piece (Ex. 6.2).

Example 6.2 Facsimile of Mozart: Quartet in D minor K. 421, i, bb. 1–8, as presented in Jérôme-Joseph de Momigny, La Seule Vraie Théorie de la Musique (Paris, 1821)

This emphasis on connection rather than articulation is indicative of the nineteenth-century movement away from metrical restraint and towards an increasingly sostenuto ideal of tone production. Liszt called for an end of ‘playing tied to the bar lines’, and Hugo Riemann (1883) wanted musical shape determined by phrase structure alone.19 Wagner considered ‘tone sustained with equal power’ as the basis of all expression, and Andreas Moser (1905) described the imperceptible bow change, and hence the seamless legato, as ‘a violinistic virtue, which cannot be too highly extolled’.20

When playing the quartet repertory in which the metrical structure is still alive and well, the features which challenge that structure only achieve their full force and gain their proper significance if that order is itself recognised and respected. For string players this metrical order is made audible through the exercise of the so-called ‘rule of down-bow’. This system was given its most extensive exposition by Leopold Mozart who, in the opening paragraph of the Preface to his Versuch (1756), describes his concern when he heard ‘fully-fledged (gewachsene) violinists . . . distorting the meaning of the composer by the use of wrong bowing’.21 In following this principle, the string player actually has a more complete experience of the conflict between metrical and other accents than is possible for woodwind or keyboard players. Because bowing consists of two contrary physical actions, which the force of gravity naturally divides into strong (down) and weak (up), playing an off-beat stress with an up-bow is not only a different physical sensation from playing it with a down-bow; it also gives that stress its proper significance and full emotional weight. Playing stressed upbeats with a down-bow, as proposed by Moser in the Peters edition of Haydn’s Quartets, misses the point, and loses the tension and forward movement which result from an up-bow execution.

François Tourte’s new bow model was created in response to the demands of players and contemporary musical tastes and performing styles. The full range of its capabilities was detailed by Baillot in 1835, but it was already in widespread use around 1800. Its increased length answered the need for greater singing power, and the wider ribbon of hair, held flat by the metal ferrule, gave a fuller tone and a sharper edge to the attack; but the feature most relevant to the new bowing style was the head which, balanced by a heavier frog, converted the upper half of the bow into a distinct area capable of producing a series of strokes of a brand-new type. The muted (mat) and dragged (traîné) strokes described by Baillot had a longer contour than the organically shaped notes of the previous century, and the specialised strokes illustrated by Woldemar (1798), each named after the violinist who had coined it (Viotti, Kreutzer, Rode etc.), mostly exploit this new area.

In contrast with these on-the-string bowings, the jumping bow-stroke associated with Wilhelm Cramer was also the product of a new bow model, that associated with his name. Similar to the Viotti/Tourte model but with a narrower band of hair, a shorter stick and a higher frog, it makes a clearer, slighter tone. It was later used by Paganini, whose light playing style also stood outside the Viotti mainstream. But it was the heavier Tourte bow, and the style associated with it, which prevailed. The jumping strokes, which did not even get a mention in the tutors of Baillot, Rode and Kreutzer (1803) and Spohr (1832), were considered by the latter to be flashy (windbeutelig) and unworthy of serious art, and it was only later in the century that such bowings were considered an indispensable part of a violinist’s technique. Thus, Clive Brown suggests that, in playing music of the earlier nineteenth century, where the present inclination might be to play faster notes in the middle or lower half, violinists of that time were more likely to have used the upper-half bowings mentioned above.22

Intonation

In baroque music the almost constant presence of a fixed-pitch instrument in any ensemble put constraints on the intonation of the other instruments with more adjustable tuning. The fixed-pitch instruments were tuned in a chosen temperament and the others had to fit in with it or ignore it. With the disappearance of the continuo in later music, ensembles were free to play in whatever tuning system they fancied, and the string quartet was perhaps the freest of all. Excepting the open strings, all its pitches were ‘bendable’.

The main influence on intonation then was the language of the new classical style itself, which, as Charles Rosen points out, depends on the system of equal temperament.23 Whereas in the older unequal temperaments D and E

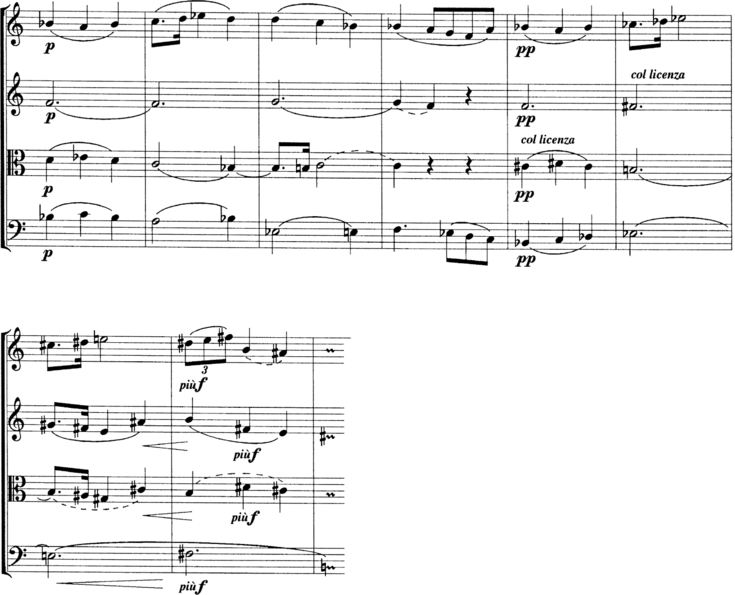

and E were two distinct pitches, in equal temperament they share one compromise pitch. A striking demonstration of the tacit assumption of the newer system can be seen in the slow movement (Fantasia) of Haydn’s Op. 76 no. 6 (bb. 35 and 36). In this crafty transition from B

were two distinct pitches, in equal temperament they share one compromise pitch. A striking demonstration of the tacit assumption of the newer system can be seen in the slow movement (Fantasia) of Haydn’s Op. 76 no. 6 (bb. 35 and 36). In this crafty transition from B major to B major, the inner parts for two bars are notated in the sharps of the up-coming key while the outer parts are simultaneously written in the flats of the key of origin. Haydn makes his apologies for the notational inconsistency with the marking of ‘c.l.’ (cum licentia) on the second violin and viola parts at the point of deviation (Ex. 6.3). In a similar modulation from E

major to B major, the inner parts for two bars are notated in the sharps of the up-coming key while the outer parts are simultaneously written in the flats of the key of origin. Haydn makes his apologies for the notational inconsistency with the marking of ‘c.l.’ (cum licentia) on the second violin and viola parts at the point of deviation (Ex. 6.3). In a similar modulation from E minor to E minor in the first movement of Op. 77 no. 2, Haydn is even more specific. Between the cello E

minor to E minor in the first movement of Op. 77 no. 2, Haydn is even more specific. Between the cello E in bar 92 and its D

in bar 92 and its D in bar 93 he writes ‘l’istesso tuono’ (‘the same note’).

in bar 93 he writes ‘l’istesso tuono’ (‘the same note’).

Example 6.3 Haydn: Quartet in E Op. 76 no. 6, ii, bb. 31–9

Op. 76 no. 6, ii, bb. 31–9

Even before the creation of the classical style there were advocates for equal temperament, notably Rameau;24 and with the increasing harmonic freedom exemplified by the above examples it came to be regarded as a virtue as well as a necessity. Momigny calls the twelve equal semitones the ‘élémens inaltérables de la musique’, and Spohr refers to the ‘theory of the absolutely equal size of all twelve semitones’. For him, ‘pure’ intonation means equal temperament ‘because for modern music no other exists’.25

Balancing all this enthusiasm for equal temperament, many players and writers have been more concerned with tunings which produce either more true intervals (particularly thirds and sixths) or more expressive ones (particularly raised leading notes) or both together, the former as ‘harmonic’ and the latter as ‘melodic’ intonation. Robert Bremner’s ‘Some thoughts on the Performance of Concert-Music’ (London, 1777), which he published as a preface to a set of string quartets by J. G. C. Schetky, contains a series of exercises in double stopping for refining the ear in judging pure intervals, and learning the physical feel of major and minor semitones, a salient feature of just and meantone tunings. Another aspect of such tunings is the pitch distinction between enharmonic pairs (C /D

/D etc.) where the D

etc.) where the D is higher than the C

is higher than the C . In 1829, Melchiore Balbi wrote that ‘even the most ordinary violin player, when unaccompanied customarily preserves a sensibilissima

syntonic distinction between two enharmonically equivalent notes’; and in 1876 the music historian Cornelio Desimoni wrote of the ‘armonia pura del quartetto’ in contrast to the piano’s equal temperament.26

. In 1829, Melchiore Balbi wrote that ‘even the most ordinary violin player, when unaccompanied customarily preserves a sensibilissima

syntonic distinction between two enharmonically equivalent notes’; and in 1876 the music historian Cornelio Desimoni wrote of the ‘armonia pura del quartetto’ in contrast to the piano’s equal temperament.26

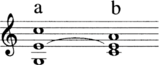

This preference for a more just intonation was shared by Viotti and Baillot,27 and in the following century Joachim, a descendant of this Viotti school (through Rode and Böhm), also showed his sensitivity to just intervals. However, both Baillot and Joachim tuned their open strings in pure fifths, which gave rise to the problem demonstrated by Joachim in his Violinschule (1902–5), namely the discrepancy between the pitch of the E required to be in tune with the G string in the first chord (Ex. 6.4a) and that needed to fit with the A in the second (Ex. 6.4b). The first finger on the E, having played chord (a) in tune, has to move up a syntonic semitone to be in tune for chord (b). This test is almost identical with the one in the Traité de Musique (1776) by the French theorist Anton Bemetzrieder. Joachim did, however, distort intervals in certain cases, namely augmented and diminished intervals, which require ‘characteristic’ intonation, also semitones in fast scale passages. In this reversal of just intonation, F is placed higher than G

is placed higher than G , G

, G higher than A

higher than A and so on.28

and so on.28

Example 6.4 Extracted from Joseph Joachim and Andreas Moser, Violinschule (3 vols., Berlin, 1902–5)

Carl Flesch took this reversal still further.29 He divided violinists who play in tune into two categories: the many who are content with the tempered tuning of the piano, and the few who, in a melodic context, raise the leading note f 2 to about a quarter tone’s distance from the g2, so that f

2 to about a quarter tone’s distance from the g2, so that f 2 is 12 vibrations higher than g

2 is 12 vibrations higher than g 2. Already as a young man he was criticised for making his semitones much too small. But even Flesch confines this reversed tuning to melodic contexts. This co-existence of ‘melodic’ and ‘harmonic’ tuning standards had already been proposed by Bemetzrieder: ‘The Virtuoso raises the sharp sometimes more, sometimes less; he plays the same flat note differently according to whether it is the minor 6th or the tonic.’ The same flexible approach is echoed by the cellist Bernhard Romberg (1840), who claimed to play the leading note higher in minor keys than in the major.30

2. Already as a young man he was criticised for making his semitones much too small. But even Flesch confines this reversed tuning to melodic contexts. This co-existence of ‘melodic’ and ‘harmonic’ tuning standards had already been proposed by Bemetzrieder: ‘The Virtuoso raises the sharp sometimes more, sometimes less; he plays the same flat note differently according to whether it is the minor 6th or the tonic.’ The same flexible approach is echoed by the cellist Bernhard Romberg (1840), who claimed to play the leading note higher in minor keys than in the major.30

The tuning of the only fixed notes, the open strings, is critical. If in a string quartet all four fifths from the cello’s bottom C to the violins’ top E are tuned pure, the C–E interval will be uncomfortably large (Pythagorean). This was overcome either by avoiding open strings, or by tempering their fifths. This second and more practical solution, already proposed by Quantz (1752),31 may have been practised more than it was ever openly proposed. The theorist Luigi Picchianti suggested in 1834 that to avoid having over-sized (Pythagorean) intervals when using open strings, ‘it is essential that the three (open string) fifths must be made a little smaller, and this is the way violinists tune them in practice, the majority of them without knowing why’.32

Playing with good intonation in a string quartet is an even greater challenge with the relatively lean string sound of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – the sound of gut strings and sparse vibrato. Tuning the fifths about a sixth of a comma small is a good solution not only for making those big cadential chords sound good, which inevitably combine the cello’s open C with the violin’s open E. The reduction in the size of the fifths, although a fraction more than in equal temperament, is still small enough to be easily accepted and it makes a good framework for ‘harmonic’ tuning, particularly for the eighteenth-century repertoire, where open strings are still part of the normal tonal palette. An aid to achieving this ‘harmonic’ tuning in chromatic passages is the use of the fingering widely used in the eighteenth century, and which persisted into the nineteenth. As described by Leopold Mozart and others, the basic principle is that of sliding the same finger between notes of the same letter (C/C , F/F

, F/F ) but using two different fingers for notes with different letters (C

) but using two different fingers for notes with different letters (C /D, F

/D, F /G). In this way the smaller sliding movement is matched with the minor semitone, and the larger space made by the use of two fingers with the major semitone. There is a speed above which this fingering can sound smudgy (which is why Geminiani rejected it) but, that apart, the application of this principle can greatly assist good ‘pure’ intonation, just as the use of bowing which is consistent with the down-bow principle can of itself ensure rhythmic and musical clarity.33

/G). In this way the smaller sliding movement is matched with the minor semitone, and the larger space made by the use of two fingers with the major semitone. There is a speed above which this fingering can sound smudgy (which is why Geminiani rejected it) but, that apart, the application of this principle can greatly assist good ‘pure’ intonation, just as the use of bowing which is consistent with the down-bow principle can of itself ensure rhythmic and musical clarity.33

Tone colour

Of all the factors which influence tone quality in string instruments, vibrato is the most decisive and the most closely related to the player’s personality. Since 1545 when Martin Agricola mentioned it as a sweetener of violin tone, most subsequent descriptions have been accompanied by advice to use it in moderation. Its overuse has been compared to a variety of physical and nervous ailments as recently as 1921, when Leopold Auer described the use of continuous vibrato as ‘an actual physical defect’.34 He found that certain of his pupils were ‘unable to rid themselves of this vicious habit, and have continued to vibrate on every note, long or short, playing even the driest scale passages and exercises in constant vibrato’. However, this very practice was considered by Carl Flesch to ‘ennoble faster passages’ and to be one of Kreisler’s positive contributions to modern violin technique.35 Support for the older tonal ideal represented by Auer was nevertheless still in evidence in 1935. In the fifty-fifth edition, ‘entirely revised’, of Wm. C. Honeyman’s The Violin: How to Master It, Honeyman finds ‘the close shake’ (i.e. vibrato) ‘a most effective ally of the solo player, but . . . one which is greatly abused, and often introduced where it has no right to appear. Indeed, with some solo players it appears impossible to play a clear, steady, pure note, without the perpetual tremola coming in like an evil spirit or haunting ghost to mar its beauty.’36 Early recordings give us evidence of this shift of taste from a relatively straight nineteenth-century tone slightly coloured by a narrow vibrato, to a twentieth-century tone in which an intense vibrato penetrates every corner of the sound.

Written advice on the application of vibrato generally proposes logical and unexceptionable principles: e.g. using it only in appropriate places (Spohr and Joachim/Moser) or never on successive notes (Baillot and Auer); and even Carl Flesch, a proponent of the twentieth-century approach, offers a balanced picture of the ideal vibrato as ‘one differentiated in the highest possible degree, one which . . . is able to traverse a gamut of emotions’.37 In practice, however, its application is much more arbitrary and less well defined. Its perception is also highly subjective. Menuhin as a young man found the tone of the Capet Quartet intolerable on account of its playing, as he thought, without vibrato.38 In fact, recordings show that all four players used a more or less continuous vibrato, which was constantly fast and varied in width from narrow to zero. The crux was that by comparison with his teacher George Enescu’s vibrato, which was wider, the relatively straight sound of the Capet Quartet did not match up to the modern idea of violin tone. Similarly when, in the first years of the twentieth century, the composer Eric Coates heard Joachim play, he was disappointed and found his playing cold. He thought ‘a little more vibrato might well have covered up (his) lack of intonation’ – perhaps a legitimate criticism of the ageing Joachim’s intonation but maybe also a modern taste for more sweetener in the tone.39 Perhaps the best recorded evidence of the nineteenth-century string quartet sound is offered by the Rosé Quartet. Flesch judged Arnold Rosé’s style to be of the 1870s, ‘with no concession to modern tendencies in our art’.40

If early recordings do give us an idea of the string tone quality characteristic of the nineteenth century, only writings and instruments can be used to attempt to rediscover the sound of the later eighteenth century. A violin in pre-modern condition played with a lighter transitional bow already defines the tonal palette to some extent, and the lighter set-up also circumscribes the extent and nature of vibrato use.

Another influence on tone quality is the material of the strings. Gut strings were in general use until the 1920s. Until then the combination of plain gut E, A and D, with the G of gut wound with silver, was the norm. Flesch noted that in the interval between the first (1923) and second (1929) editions of his Die Kunst des Violinspiels the metal E string had ‘completed its victory throughout the violin-playing world and the gut E is hardly used any more these days by professionals’.41 The aluminium D and the steel A followed, to complete the transition from gut to metal. But there were players who continued to play on gut against general practice, and the early resistance to steel was upheld by supporters of the old aesthetic. In 1935 Liza Honeyman, daughter of the now deceased author of The Violin: ow to Master it, wrote: ‘Primarily, the violin as we know it was not designed to be strung as a banjo or mandoline. Pupils of the late Prof.  ev

ev ík used a set of steel strings for practice hours, and the well-known violinist P

ík used a set of steel strings for practice hours, and the well-known violinist P íhoda does so on the platform; but, as his violin is an old and apparently thin-wooded one, it is a nightmare to look at and listen to!’42 Her preference was for silk.

íhoda does so on the platform; but, as his violin is an old and apparently thin-wooded one, it is a nightmare to look at and listen to!’42 Her preference was for silk.

The reliability of metal strings was a great comfort to violinists who had previously had to play in constant fear of strings going wildly out of tune, squeaking and breaking. In the age of gut, though, violinists did know how to cope with these likely accidents. Dittersdorf was taught to learn to play all his concertos on three strings in anticipation of breakage. The same teacher also advised him to check and change his strings before going to bed so that they could stretch overnight.43 Breaking strings could even be turned to dramatic advantage. Alexandre-Jean Boucher (1778–1861), the charlatan virtuoso who bore a striking resemblance to Napoleon, suffered a broken E string while playing his own quartet. ‘I quickly caught the remains of the string in my mouth to prevent it from interfering with the other strings and continued as if nothing was amiss . . . You should have seen the musicians gaping in admiration, and all the audience who came closer in order to hear better and to see if I would slip up.’44 Joachim, aged twelve, at his debut in Leipzig, ‘had hardly begun when his E string snapped. With the greatest sangfroid he put on another and continued to play, every now and then tuning the new string in the tuttis, as calm and secure as if nothing had happened.’45 Flesch said that he would never allow a pupil to appear in public unless he were assured that he could adjust his strings in the manner shown in Ex. 6.5.46 Flesch also offers emergency measures to deal with squeaky strings, including accented bow attack, greater bow pressure with reduced amount of bow, and avoidance of all light strokes and jumping bowings. ‘The jumping bowings are to be replaced by a small détaché. As you see, a completely altered playing style quite against the basic principles of violin playing, and so substituting a lesser for a greater evil, inferior tone production instead of squeaks – nevertheless a real improvement.’47

Example 6.5 J. S. Bach: Chaconne (Partita No. 2 in D minor) extracted from Carl Flesch, The Art of Violin Playing, i, p. 11

Today’s players on gut strings may have some advantage over their predecessors. Whereas in 1935 ‘even the best of gut E strings are a lottery – sometimes breaking immediately they are tuned up’,48 today we have a choice of easily available strings of a consistently high quality. Better still, the use of varnished strings, which are less susceptible to changes in humidity, further reduces the element of risk involved in playing on gut.

Tempo

Finding the right speed for a piece of music is as much a gift as a skill. It will not be said of many players, as it was of the Dresden concertmaster Pisendel, that ‘he never – not even once – made a mistake in the choice of tempo’.49 But this natural sensitivity, with which Pisendel was said to be so richly endowed, needs to be coupled with skill acquired through experience. This skill includes assessment of internal features of the music such as note-values and harmonic density, the character of or occasion for the piece, the size of the hall, the choice of time signature and the movement headings. These last, in the hands of Haydn and Mozart, were ordered into a multi-layered and subtly nuanced palette of speeds. In his mature quartets Mozart uses sixteen different movement headings, and Haydn’s quartets contain close on forty. ‘Allegro’ alone appears with seven different qualifying words or phrases. Beethoven continued this expansion of the vocabulary, but in the meantime Maelzel had produced his metronome and in 1817 was promoting it in Vienna. This device made it theoretically possible for the composer to fix the speed of his music precisely; although it was generally recognised that in practice it could only give a general idea, this was at least some safeguard against a variety of interpretations, which could depend on national style, school of playing, or merely fashion, aside from the personality and judgement of the performers themselves.

Beethoven was the first significant composer to issue metronome marks for his own works – in 1817 for the first eight symphonies and in 1819 for the quartets up to Op. 95. About half the marks in the quartets are surprisingly fast, mostly by an increase of two or three metronome notches, but in some cases more, even to the extent of complete incompatibility with the movement headings.50 Several attempts have been made to explain this, including the suggestion that by the time he came to supply the marks perhaps ‘his ear had grown impatient with some of his old music’.51 Two theories seem plausible. At quartet performances Beethoven was too busy beating the time to be able to make a record of it.52 He therefore probably made his judgements either at the piano or in his head. As Brahms pointed out to Clara Schumann, who was about to set metronome marks for her husband’s music, ‘on the piano . . . everything happens much faster, much livelier and lighter in tempo’. And estimates made in the head against a ticking metronome, as Tovey observed, are likely to err on the fast side.53 But these markings, if they need to be taken with a pinch of salt and may even include actual errors, nevertheless give a strong indication of Beethoven’s intentions. They are also consistent with the slightly later markings which Czerny attached to the piano music of Beethoven,54 whose pupil and close associate he was, and which Hummel and Czerny added to their piano arrangements of Haydn and Mozart.55 Mendelssohn’s and Schumann’s metronome marks for the fast movements of their quartets also tend sometimes to the unfeasibly rapid, but it is the faster tempi of their slow movements which indicate a more radical difference of musical approach. Even Dvo ák, whose metronome marks do not stretch credulity, indicates relatively flowing slow movements. The contrast is particularly striking between the turgid or sentimental renderings of slow movements in some early-twentieth-century recordings and the fleeter, lighter conception implied by these composers’ own markings.

ák, whose metronome marks do not stretch credulity, indicates relatively flowing slow movements. The contrast is particularly striking between the turgid or sentimental renderings of slow movements in some early-twentieth-century recordings and the fleeter, lighter conception implied by these composers’ own markings.

In the same year in which Beethoven published the metronome markings for all his quartets to date, Spohr’s Op. 45 quartets also appeared, with both pendulum and Maelzel marks. The speeds are in general as practical as one would expect from a performer/composer, but the slow movements are truly slow.

Although tempo instructions originating from the composers themselves naturally carry most authority, those from other sources can be significant. For the pre-Maelzel quartets of Haydn and Mozart, the source closest in time is Czerny’s four-handed arrangement of Mozart’s quartets, from the late 1830s. Having made allowance for the increase in tempo associated with the transference to the piano, it is the slow movements and Menuets which are notably faster, whereas the outer movements mostly conform to present-day expectations.

Further removed in time, in 1854 the Polish violinist Karol Lipi ski added Maelzel marks to all of Haydn’s quartets, in an edition based on Pleyel’s Paris publication of 1801, for which Baillot, himself famous as a quartet player, was partly responsible. In general Lipi

ski added Maelzel marks to all of Haydn’s quartets, in an edition based on Pleyel’s Paris publication of 1801, for which Baillot, himself famous as a quartet player, was partly responsible. In general Lipi ski’s slow movements are very slow and his first and last movements mostly moderate, but his minuets are almost without exception very fast. This approach to tempo could be seen as an aspect of his playing style, which was in the solid tradition of Viotti and Spohr; on the other hand it tallies in part with the report, in 1811, that Mozart and Haydn ‘never took their first Allegros as fast as one hears them here. Both let the Menuetts go by hurriedly.’56

ski’s slow movements are very slow and his first and last movements mostly moderate, but his minuets are almost without exception very fast. This approach to tempo could be seen as an aspect of his playing style, which was in the solid tradition of Viotti and Spohr; on the other hand it tallies in part with the report, in 1811, that Mozart and Haydn ‘never took their first Allegros as fast as one hears them here. Both let the Menuetts go by hurriedly.’56

In search of the right tempo, the quartet player still needs to exercise musical judgement in combination with serious consideration of the historical evidence, always keeping the mind open to new ideas.

Text

‘The modern practice . . . of “editing” recognised classical and standard works cannot be too severely condemned as a Vandalism’, wrote Moser in 1905.57 He cites Spohr as having particularly suffered from this treatment. Spohr’s quartets are certainly marked in great detail: fingerings, bowings, articulation, metronome marks and even vibrato, leaving no room for doubt as to his intentions. Yet, less than fifty years after his death, his works were being reworked, due partly to ‘an utter lack of knowledge regarding certain peculiarities in his style of composition and treatment of the violin’. The scope for such misinterpretation is even greater in music which is further removed in time and with fewer performance directions.

Moser produced editions of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven quartets, outlining his editorial policy in the Preface to his collection of thirty celebrated Haydn quartets (1918).58 Although this policy shares some of the aims of a modern critical edition, it differs mainly in its declared representation of the ‘then current practice of the Joachim Quartet’. This was suitable in the case of Beethoven’s quartets. Joachim was taught by Joseph Böhm who, during the 1820s in Vienna, was closely associated with the new chamber music of Beethoven and Schubert. Both Böhm and Beethoven had their connections with the new style of the Paris Conservatoire, Böhm as a pupil of Rode and Beethoven through his association with Kreutzer and Rode. So the fingerings and bowings of the Joachim/Moser editions, which reflect Conservatoire practice, may also represent the intentions of Beethoven and Schubert. In the case of the editions of eighteenth-century works, however, this is obviously not appropriate.

A modern critical edition attempts to remove such third-party interference between the performer and the composer. It also takes on the task of tracing the often tortuous history of the sources and assessing their relative significance in the attempt to reveal as closely as possible the composer’s intentions. Attractive as it may be to play from facsimiles of early printed editions or hand-written copies, these are unlikely to contain the whole truth and will probably have a fair share of omissions, ambiguities and actual mistakes. They are, though, unlikely to have as many impossible page turns as supposedly practical modern editions (which are also prone to misprints); and in the case of works which exist in only one source, or for which the best source is a printed one, playing from an old source can combine authority, practicality and good looks. In any case, with the increasing availability of facsimiles of autograph scores and first editions, there are ever more opportunities to follow Moser’s suggestion that before accepting the given text, we can consult the original.

Ornamentation

Attitudes towards alteration of the notes on the page have, as in the case of vibrato, generally ranged from written pleas for moderation to reports of excessive or inappropriate practice. Moser wrote (1905) that to prevent their music being drowned in embellishments, composers had been forced to give such precise instructions that ‘it has now become a point of honour to make no alteration of any kind in a composition’.59 The players responsible for this situation were such as Boucher, whom Spohr heard in 1818 when he ‘played a quartet of Haydn, but introduced so many irrelevant and tasteless ornaments, that it was impossible for me to feel any pleasure in it’.60 In fact Boucher was so renowned for his gratuitous additions that when he agreed to play a piece ‘textuellement’, i.e. sticking to the written notes, his audience who ‘feared that he would not hold to his promise . . . was agreeably surprised’ when he did.61 Ferdinand David, pupil of Spohr, friend of Mendelssohn, and admired quartet leader, was also accused, particularly in later life, of making tasteless additions to Classical quartets. Baillot, on the other hand, was admired for his quartet playing in which there was ‘no departure from the character of the piece and no alteration by parasitical embroideries’.62 Spohr’s own advice in the case of what he calls the ‘true quartet’, as opposed to the leader-dominated quatuors brillants written by himself, Viotti, Rode and others, is that ornamentation should be limited to those sections which are clearly solo, with the other parts mere accompaniment.63 Such opportunities are to be found in the slow movements of early quartets of Mozart and Haydn, notably Haydn’s Opp. 9 and 17 where, in addition, cadenzas are frequently called for at cadential pauses.

The complexity and quality of the music is also a guide as to whether embellishment is appropriate. Music which is the result of long and hard work (‘frutto di una lunga e laboriosa fatica’)64 by Mozart is unlikely to be improved by the spontaneous ideas of even the most inspired quartet player, whereas the baser metal of his lesser contemporaries may well benefit from a bit of gilding; and an awkward compositional corner can sometimes be more smoothly negotiated with the help of some well-chosen additions. As an example of the first situation, Baillot quotes the opening of the slow movement of Mozart’s ‘Dissonance’ Quartet as a case of ‘Chant Simple’, which ‘must be played as the composer has written it’.65 The reason becomes clear at the theme’s second appearance, where Mozart gives his own ornamented version. The second situation is illustrated by Spohr, whose description of his teacher Franz Eck playing a quartet by Krommer praises ‘the tasteful fioriture by which he knew how to enhance the most commonplace composition’.66

Pitch

At the time of the emergence of the string quartet pitch varied not only from town to town but, within each town, between the different churches, theatres and chambers. Broadly speaking, though, pitch levels rose in the course of the eighteenth century and this rise accelerated in the early part of the nineteenth. In 1860, in a footnote to an updated English edition of Otto’s Treatise on the Structure and Preservation of the Violin, the translator described ‘the excessive rise in the musical pitch which has taken place since the commencement of the eighteenth century’. He reckoned that from Tartini’s time (1734) to 1834 pitch had risen a semitone, and during the next thirty years another semitone, creating increased pressure on ‘the masterpieces of the great violin makers . . . which they were never constructed to bear; and hence, also, another argument in favor [sic] of a reduction of the musical pitch’.67 Several attempts were made in the first decades of the nineteenth century to lower pitch again and standardise it. In 1813 the London Philharmonic Society produced a tuning fork at a1 = 423.5Hz, and in 1825 George Smart, who had been one of the four members to approve this pitch, went on a tour of Europe testing his Philharmonic fork against every orchestra, organ, piano and string quartet that he encountered. Half of his readings were ‘exact to my fork’, but in Vienna the pitch was generally ‘rather above my fork’, as it was when he was present at the first performance of Beethoven’s Op. 132 at the lodgings of the music seller Schlesinger, who published the work two years later.68

Pitch continued to rise through the century in the interests of instrumental brilliance but to the detriment of singers’ health. In France a ‘diapason normal’ of a1 = 435Hz was established by law in 1859, but decisions made at a conference in Vienna in 1885 led to the acceptance of a1 = 440Hz, a decision confirmed again in the next century. The practical desirability of having a standard pitch, recognised in the mid eighteenth century, became even more acute with the increase in recordings in the 1970s and in the use of ever more sophisticated splicing techniques. The compromise pitch of a1 = 430Hz adopted then for classical repertoire would appear to be very near that of Beethoven’s Vienna, and although possibly lower than that of the later part of the century, also makes a good median pitch for a quartet programme with a broad range of repertoire.

Seating plan

There is scant evidence of how the players were arranged in an eighteenth-century quartet, but iconography suggests that just about every possible seating permutation seems to have been tried in the nineteenth century.69 Evidence can be divided into two broad categories, according to whether the two violins are side by side or opposite each other. Two of the most popular arrangements were represented by Joachim, when playing with his Berlin quartet, and when playing with Ries, Straus and Piatti in London. In the former the violins sat facing each other (Fig. 3.2). This pattern, reflecting standard orchestral seating, was the most favoured during the nineteenth century, particularly in Germany. In Joachim’s London quartet, on the other hand, the violins sat side by side, an arrangement which rivalled the Berlin pattern in popularity at that time and became standard in the twentieth century, with either the viola or the cello sitting opposite the first violin. For performance of quartets in the more conversational style of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and their imitators, the seating with antiphonal violins has the advantage, both for the violinists themselves and for the audience, of separating the two treble lines and so clarifying the texture.

Conclusion

A string quartet wanting to get closer to the spirit of the composer and his times certainly needs a reliable and transparent edition. It would be assisted by the use of instruments, bows and fittings contemporary with the music, but stylish playing need not depend on this, any more than it is guaranteed by their use.

The most striking element of any playing style is sound quality, which is determined principally by the type of strings, the model of violin and bow employed and the application of vibrato. Of these, vibrato is the most decisive and personal. Although appropriate articulation, accentuation and phrasing are easier to achieve with a ‘period’ bow and violin, they can be emulated with ‘modern’ equipment. Tempo selection is hardly affected by the choice of instrument or bow, and intonation, although closely linked with sound colour, needs independent consideration.

It is, therefore, the extent to which players are prepared to modify their performance style, with or without period instruments, and how far audiences will go along with them, that will determine how closely one can approximate the composer’s original conception. In the late twentieth century, a range of new performing styles for early music was heard. The elements they had in common, in particular their leaner sound, were generally accepted, indicating a shift in musical taste. Whether any future shift in popular taste will take the historical performance of string quartets further along this road remains to be seen, but there is no doubt that an increased awareness of past performance practice can demonstrate how much there is to discover in any such attempt to get closer to the heart of this rich repertory.