Chapter 3

Long Knives

The long knives used by ranger troops in the colonial period, especially during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), and by long hunters during a similar period were the first knives in America that could be called tactical by our definition. These knives, which were commonly seven to ten inches in blade length with the longer lengths being more popular, were also part of the reason Native Americans dubbed the rangers and long hunters Long Knives. From the Native American perspective, the long knife, carried daily and used both as an everyday tool and fearsome weapon, was a defining characteristic of these groups of daring and adventurous colonists.

The gear and weapons used by the rangers were the same as what was used by the general population; in fact, the rangers were often drawn from and part of the general population rather than a professional military. Their long knives were, generally speaking, the same as the knives used in colonial kitchens, much like those used in kitchens today.

Daniel Winkler Belt Knife with tack decoration and a Damascus blade of six inches. © PointSeven Studios.

Some historians have written that the Native Americans named these men Long Knives because they carried swords. As a result of reading dozens of first person accounts written by long hunters, rangers, and ordinary colonists—including the journals of Daniel Boone, the most famous of the long hunters, and Major Robert Rogers, who formed and led the most famous American Ranger company, Rogers’ Rangers—I am convinced this interpretation is incorrect. As a result of reading dozens of first person accounts written by long hunters, rangers, and ordinary colonists, including the journals of Daniel Boone, the most famous of the long hunters, and Major Robert Rogers formed and led the most famous American Ranger company—Rogers’ Rangers.

In addition, I have read transcripts of oral history taken from Native Americans, including the Mohawk, Seneca, Iroquois, Wyandot, Shawnee, Potawaname, and Cheyenne tribes, that came into contact with rangers and long hunters and who named these men Long Knives. Over the years, I have visited archaeological excavations and museums devoted to the American history of this period and interviewed archaeologists, historians, and museum curators. The evidence is clear. The Native Americans called long hunters and rangers Long Knives because they carried long knives, not swords.

Daniel Winkler Rifleman’s Knife with twist pattern, Damascus eight-inch blade, an overall length of thirteen inches and a deer antler crown handle © PointSeven Studios.

Officers in the Continental Army carried swords, unlike long hunters, whose gear had to be multifunctional. I have found no instance of rangers being equipped with swords rather than long knives and tomahawks—the only exception being a few ranger officers who carried swords.

The long hunters relied on their knives as both daily tools and weapons. With their long knives, they skinned and butchered enormous quantities of wild game during their extended treks “over the mountains” from Virginia to the “dark and bloody hunting grounds,” which are now Tennessee and Kentucky. One account lists the equipment carried by a group of long hunters who had secured 2,400 deerskins. There are no swords on the equipment list. They also used their long knives in hand-to-hand combat. This same group of hunters was returning to Virginia when they encountered a band of Native Americans who objected to the colonists poaching on their hunting ground in violation of a treaty. A fight ensued between the Native Americans and Long Knives, and after the first exchange of gunfire, the fight quickly went to “tomahawks and long knives.”

Such armed encounters involving hand-to-hand combat with knives and tomahawks were common on the frontier. So common that Rogers’ 28 Rules of Rangering mentions the tomahawk as a weapon. Rogers’ Rules do not mention the knife. I think this is due to the ubiquitous nature of the knife; every man had one and carried it daily even if he did not have a tomahawk. Knives were so much a part of everyone’s daily gear that they did not need to be mentioned.

Anyone who doubts the primacy of the long knife, that rangers fought with knives, or the effectiveness of their long knives has only to read a few of many original accounts of the rangers’ battles. One mission undertaken by Rogers’ Rangers shows the importance of the long knife over even the tomahawk.

With a small band of men, the rangers set out to travel on foot and by stealth over two hundred miles through territory occupied by more than fifteen thousand French and their Indian allies. The object of the mission was to retaliate for numerous depredations against colonial settlers and, if possible, to rescue prisoners believed to be held by a band of Native Americans, called the Cold Country Cannibals due to their practice of roasting and eating prisoners.

After more than two weeks of skirmishes, in which the rangers prevailed due to aggressive tactics and fierceness in hand-to-hand combat, and travel through chest-deep bogs and the most difficult terrain, the rangers came upon a village of an estimated five hundred Native Americans. The rangers hid in the forest until the village slept. Then, with the utmost stealth, they infiltrated and dispatched more than two thirds of the warriors with their knives, coming upon them as they slept and eliminating them silently. A general battle ensued when one of the warriors raised the alarm. Since most of the warriors had already been killed in the darkness, the rangers were able to defeat the entire encampment, killing more than two hundred warriors in total. Only two rangers lost their lives. No women or children were killed. The rangers freed five captives and found more than six hundred scalps taken from colonists. It is highly unlikely that the outcome would have been the same if the rangers had not been successful with their tactics: stealth and the silent use of their long knives. Word of the rangers’ victory quickly spread through the tribes. Is it any wonder the name Long Knives became a term of fear and respect?

Daniel Winkler Large Rifleman’s Knife, with a twelve-inch Damascus blade, overall length of seventeen inches, and elk antler crown handle © PointSeven Studios.

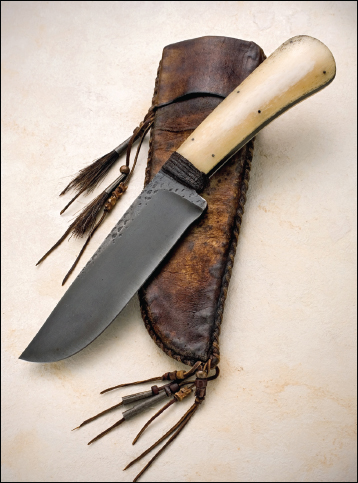

For the most part the knives used by the Long Knives were products of local blacksmiths. With no modern knife-making tools, such as belt grinders, grinding wheels, temperature-controlled heat-treating ovens, and so on, the blades came directly from the smithy, where they had been shaped by muscle, hammer, and anvil and tempered by the coals of the forge. Deer antler was readily available at little or no cost and made into durable, solid handles with a rough texture providing a secure grip. Blade shapes varied and included clip points, spear points, straight knives, and upswept points. Almost all were single-edged. Many were similar to today’s chef’s knives. Generally, the blades were somewhat heavier than the knives from England and considerably less expensive, while giving up nothing in cutting ability, toughness, or quality.

Cutting tests and other testing have demonstrated that some of the available examples of long knives from this period were, and are, equal to knives available today. Rockwell testing of surviving examples reveals that some of them were differently tempered. Some had a distal taper. Most had flat ground blades, some had convex blades, and virtually all had convex edges. Before modern equipment was widely and inexpensively available, hollow grinding was used only on fuller swords to reduce blade weight.

I have had the opportunity to handle a number of long knives from the colonial period. One in particular, handed to me by the curator of the Indiana Military Museum in Vincennes, Indiana—the site of one of Rogers’ Rangers most famous exploits—caught my imagination with its uncompromising and clearly defined purpose.

The sides of the blade were rough, still marked from the maker’s hammer, a textural invocation of primal craft. The blade was ten inches long with a graceful curve from hilt to tip and hefty without being heavy or clunky. It was hafted with antler from a deer taken in the wild forest that once stretched unbroken from the eastern seaboard to the great desert. I imagined thrusting this knife, sheathed in rawhide and buckskin, into the wide sash tied around my hunting shirt as I prepared for an expedition into the green wilderness of the Northwest Territory.

Imagination is all very well, as far as it goes. But it may prove difficult and expensive to acquire ownership of an original long knife. However, it’s no trick at all to obtain a replica crafted by hand and forge tempered by modern day craftsmen who work in the traditional style with traditional materials.

Replica of a Colonial-era French trading knife.

Today there are a number of knifesmiths who have revived the long knife tradition and make replicas that look and perform like their ancestors. Some of them style themselves as makers of buckskinner’s knives, others call their products long knives or camp knives, a term and style of knife popularized by Bill Moran some years ago.

Daniel Winkler and Wayne Goddard are two men who have worked in this style and whose knives I have used and can recommend without reservation. They are both Master Smiths of the American Bladesmith Society. I have used knives forged by both men and found them to be extraordinary, both in appearance and performance. Any member of the ABS can make you a fine long knife that is equal to or better than those carried and used by the American rangers or the long hunters.

Michael Mann, of Idaho Knife Works, is another knifesmith whose work I am familiar with. He makes good knives in the long hunter style. H & B Forge also works in the old tradition and is well-known among the buckskinner crowd for forging hawks and throwing knives drawn fairly soft so as not to break with the impact of repeated throwing. Some manufacturers, such as Boker and Cold Steel, also catalog knives reminiscent of the era.

A somewhat easier approach to getting a hold of a long hunter’s knife is to simply buy a carbon steel kitchen knife. The heritage and linage is clear; long knives were derived from butcher knives. A few years ago, I did exactly this when I lacked a long knife and the need for wilderness was lying heavy on me after a series of long, dull business meetings.

Daniel Winkler Lost Lake Camp Knife, forged six-inch 1084 blade with an overall length of eleven inches © SharpByCoop.

A Long Knife in a French Forest

There is a long knife on my desk as I write, an old chef’s knife that was once rusty but now scrubbed clean, a Sabatier with a ten-inch blade. I bought this plain, honest knife deep in the heart of France, in what the French call La France profonde. I wanted a long knife as a good companion for a night or two in the forest.

After too many days of smoky rooms and talk, I dumped my computer and other gear in a locker at the Gare du Nord and grabbed the first fast train south with a change of clothing and a few odds and ends stuffed in a small rucksack.

I was headed for the Auvergne region and a national park that sprawls over a mountain range, where stone houses have been abandoned and become ghost villages. Deer herds are everywhere, stepping delicately through the green woods and wandering along broken and unused blacktop roads. Crumbling castles and Roman ruins add to the mystery and beauty. Wild boar—large, red-eyed, and mean-tempered—shuffle and snort through the underbrush. A friend, Henri, hunts wild boar each fall in this area with a spear. I had an encounter with Sir Swine the previous year and wanted something long and sharp by my side for this little excursion—thus the Sabatier long knife.

In a small village store I found my heavy, ten-inch Sabatier chef’s knife. Any chef will tell you that the ten-inch chef’s knife is the best all-around knife. Forget about four-inch paring knives. If you have some real work to do, what you want is ten inches of good carbon steel. The long hunters and rangers knew that, too.

Sabatier carbon steel chef’s knife with rucksack.

The Sabatier is forged in one piece with handle scales riveted in place. It is strong and durable for the daily demands of professional use. The flat grind produces little drag when cutting. The original design was inspired by a medieval dagger, which served as a weapon as well as a tool in those days. Then it came to America and wound up in the belts of many rangers and long hunters. An integral design such as this from a custom maker will run you several hundred dollars. This masterpiece of ordinary factory steel, if new, would cost you about fifty bucks. This one cost considerably less.

The old knife had been used and neglected. There was rust on the blade. It was covered with dust. It was dull. But the blade balanced well in my hand, and it felt like a knife that could be trusted. I bought it. I also bought a small thick plastic sheet, the kind used for covering cutting surfaces, a roll of tape, and a sharpening stone. When warmed over a stove, shaped around the blade, and secured with a couple of layers of tape, the plastic sheet became an effective sheath for the big blade. A good scrubbing with an abrasive kitchen cleaner removed the rust. Twenty minutes with the stone put a ferocious edge on its carbon steel blade. With my long knife tucked into the back of my belt and a few supplies in my rucksack, I was ready, at least for a walk in the woods.

That night, after a day spent on trails that were centuries old, I camped alone halfway down a hillside. Below me I could hear deer come to water in the small stream. Above, clouds scudded across a full moon, the kind of moon the French call the moon of loup-garou, the werewolf. I kindled a tiny fire no larger then my hat in an old stone circle, grilled a venison chop from the village meat market in the coals, and ate it from the point of my knife while drinking a bottle of the rich red wine from Cahors that is sometimes called black wine. The firelight flickered on the big Sabatier blade, and I was glad to have it. There is nothing more elemental to man than a campfire in the forest with red meat cooking in the coals and a sharp blade close at hand while the night shifts and turns. Water splashed over the stones in the stream below and wind rustled the leaves in the trees around my small clearing. Time passed slowly as I sat by the fire and listened to the night.

Moonlight moved across the ruins of a medieval castle on the crest of a ridge on the other side of the small steep valley, and I imagined life as it must have been in the twelfth century. The castle would have been kept in good repair. War was constant then—a clash of steel, screaming horses, and desperate men. I also thought about Rogers’ Rangers and their attack on Vincennes after a long trek through a harsh winter.

I held the long blade of the old Sabatier up to catch the moonlight and watched a drop of pearly moonshine slide up and down the blade as I moved it. I drank the last of the wine to keep off the chill and dreamed the fire until it died. This is a term aboriginal Australians use. Dreaming the fire, is staring into the flames and letting your mind wander into Dreamtime, or what I call Tao Space. It’s a place where time ceases to exist and all things become as one. I dozed and watched moonrise and moonset, and in the early dawn with a dew-damp blanket from the hotel around my shoulders, I watched a fox lope through the clearing below me.

No, I did not have to fight off a wild boar or a loupgarou with my Sabatier. Its actual utility was limited to slicing venison, getting some kindling, and a few other mundane tasks. But I would have been poorer without it. The ten inches of steel came with its own poetry and brought a connection back over the centuries to the Roman soldiers and the medieval knights who walked these hills, sat by fires like mine, ate meat cooked in coals, looked into the night with sharp steel close at hand, and dreamed dreams while drifting and gazing into the fire and wondering what tomorrow would bring. And I remembered a ten-year-old boy who took his mother’s kitchen knife to the woods and imagined he was one of Rogers’ Rangers.

The long knives of the rangers and long hunters were also used by ordinary colonists and were important tools and weapons well into the nineteenth century during the mountain man era and the westward expansion. Long knives were often referred to as butcher knives because that was their primary day-to-day function. Game formed a large part of the diet, and the butchering of game was an everyday affair. Long knives were also used for everyday tasks that life on the frontier required, from peeling bark to cutting buckskin for clothing. It was this combination of everyday usefulness and fearsome weapon that made the long knife the tactical knife of its era.