Chapter 15

Big Knife or Little Knife

As far as I can tell the little knife versus big knife argument got started with Nessmuk, an outdoorsman and writer of the early twentieth century. Nessmuk, whose work I much admire, advocated for a thin, four-inch fixed blade as the best all-around working knife for the outdoorsman. The thing is, Nessmuk always had a hatchet with him, and he was focused on life in a relatively benign forest. If you’re going to tote around a hatchet, you can get by with a handy little blade in a temperate forest, no problem. If you don’t have that hatchet, a machete in the tropics, or a pry bar in an urban setting, you might need something more substantial to deal with events you encounter in today’s world. Nessmuk never had to deal with a high-rise building coming down on his head.

During the past few decades the big versus small argument has gotten downright silly. A large crowd of folks who unfortunately have a good deal of influence take a vehement position, against all common sense, that all anyone ever needs is a little knife and that big knives are an indication of that Freud thing—you know, big cigar, little . . . whatchamacallit. I’ve been told that all you need is a pocket-watch-sized folder for any job, that lockbacks are for sissies who don’t know how to use a knife, and that any cowboy can dress out a beef critter with a razor blade. Yeah, right. All you need is love too, until you want dinner. There is a reverse machismo thing going on here—mine’s littler than yours.

Cold Steel Bushman—a handy knife to have in the bush.

Moras (left to right): Model 2010, Model 2000, 780 Tri-Flex, 840 Clipper, and 840 Carbon. Handy, sharp, and affordable.

I can dress out a deer with a sharp rock, maybe not as well as our Paleolithic ancestors, but good enough to get to meat. That doesn’t mean stone knives are the best butcher’s tools. If they were, there would be a big business in selling stone knives to butchers, chefs, and other professionals. What a small knife has going for it is convenience of carry. At the end of the day, that’s quite a bit. It may mean the difference between having a knife and not having one. But that doesn’t mean a small knife will do the job any better or as well as a big knife.

Ask any professional chef which knife he would select if he were limited to one. Invariably it will be a ten-inch chef’s knife. Professional butchers will chose a ten-inch butcher knife if pushed to use one knife. In every climatic zone on our planet where people live close to the land, they use big knives as their daily tool: machete, bolo, or parang in the tropics; the Leuku or Sami in the Artic. When I was trained in survival, the dogma was big knife, small gun—normally a .22 target pistol—if you were down to basics. That’s worked for me and many others decades, and it still applies today. Check out the SERE training sites and you’ll see it’s still big knife, small gun. That’s because the combination still works.

My daily carry is often a tough, four-inch fixed blade. With it and a baton, I can go through fire doors and auto bodies. I can construct a shelter, cut some firewood, and dress game. But I could do all that and more with, say, a ten-inch Bowie or camp knife and do it faster. However, in an emergency I probably won’t have that big knife at hand. My big knives reside in my bag, not on my person.

Tramontina machete with a twelve-inch blade.

Occasionally I attend gatherings of survival experts from around the world. Usually an interesting crowd shows up: archaeologists, anthropologists, Native Americans, mountain hippies, active duty Special Forces soldiers on leave, retired military, primitive skills people who live as aborigines, sometimes actual aborigines, and all manner of outdoorsmen, hunters, and trappers. At one gathering, I decided to ask everyone their opinion on the big knife, little knife question, partially because I was curious about their answers and partially because I’m just nosey and wanted to know what knives everyone was carrying.

Knives of Winter Count.

Everyone had knives. There were long knives, short knives, big knives, and little knives. There were knives with beautiful horn handles, inexpensive utilitarian blades, hand-forged works of art, high-tech marvels, and low-tech stone knives. There were machetes from Brazil, laminated blades from Sweden, and jackknives from old-line American manufacturers. Everyone had at least one knife, and most people had two or three. Everyone, even the students who came for basic classes, knew the importance of a good knife. For many of the instructors, survival conditions are just how they live. These folks know a good deal about using knives.

The primitive skills folks can get by without any kind of knife. They just chip a sharp edge out of a handy rock, cut down a sapling, and haft a larger sharpened rock to it. Now equipped with knife and ax, they can set up housekeeping and fix dinner just about any place on the planet. But given a choice, they have knives. They know that a good knife will save labor and make life easier in the field.

There were more than one hundred instructors at that event, and I talked to at least seventy of them. So what do they use? What is the answer to the big knife, little knife question from those people’s points of view?

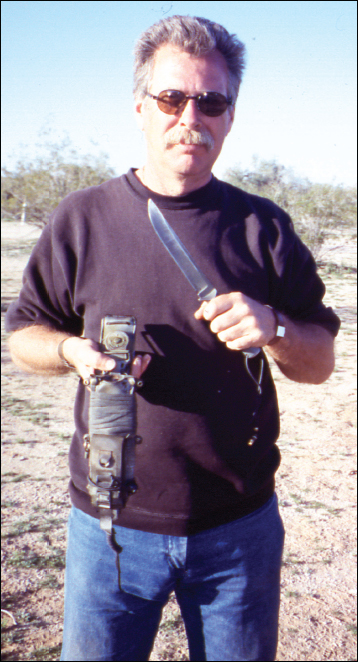

Hawk Clinton makes knives and uses them daily at his remote desert residence. He codesigned a bush knife with Tai Goo that is in wide use as the big knife among survival instructors. Tai forges the blades, and Hawk makes the handles and sheaths. Hawk prefers simple carbon steel and horn or wood handles for his knives, and he carries a lot of knives. As we talked, he showed me his neck knife, a boot knife, and a belt knife. My impression was that there were probably a few others tucked away somewhere in his buckskins. If he would let you hold him upside down and shake him (unlikely), you would probably get enough knives to open a store. Hawk doesn’t leave home without his big knife.

Albert Abrvil served with Phoenix SAR (search and rescue) for twenty years. His Apache heritage guides his approach to the natural world. When it comes to knives, he is very perceptive. “These guys know what they are doing. If you look at the common factors in their choices, you will see that they are in agreement more than in disagreement. The big knife is it—because it does more with less effort. But the small knife is always with them.”

Albert has one tool he won’t leave home without: a modified Tramontina machete. By re-profiling the point into a spade shape, he has a tool that will chop, pry, and dig with equal efficiency. “In the desert, you need to dig for water. Also certain roots are primary food and medicine items. This works for everything.” Many of Albert’s modified machetes were in the hands of other instructors, and I brought one home myself.

Chris Reeve Sable with a handle wrap by Rob Withrow.

Karin Drechsel is a museumologist who works with archaeologists. From Köln, Germany, Karin has worked on digs around the world, including in Israel, where she discovered some of the oldest examples of stone knives in the Middle East. She spends much of her time in the field and always travels with her four-inch bladed Helle knife. It is of traditional Scandinavian design with a laminated blade, wooden handle, and leather sheath. “This is my indispensable tool. I use it every day in the field. Besides being the most functional knife I could find, it is also nonthreatening. I travel many places where political tensions are high. This doesn’t look like a weapon.” She also has a twelve-inch machete in her bag. Although Karin is not a survival instructor, she is a highly intelligent knife user who spends a great deal of time in the field in locations around the world.

Although the one hundred instructors had at least three hundred knives of considerable variety between them, their choices were consistent. Everyone agreed that a big knife, nine to twelve inches, was it. In a survival situation, if you could choose one knife, take the big knife. Although everyone knew how to baton a small knife through a pile of lumber and could dress out Godzilla with their utility knives, they agreed that the big knife would do the small knives’ chores much easier and faster then the reverse. It was also understood that in an unexpected emergency situation rather than a planned trip to the field, they would probably only have a small knife with them. For that reason, most of them had both. The small knife is handier for small work, and it has the critical advantage of being highly portable and easy to carry. It is also more acceptable in today’s world. The machetes and the like live in rucksacks and duffle bags. So, curiosity satisfied. I wasn’t becoming delusional in my advanced years. Big knives are it. But there’s a big caveat: little knives get used the most because they’re more portable. Little knives are mostly what people have with them. It’s not really one or the other. Both are needed.

Swiss Army Knife with a fire starter.

Karin Drechsel at Winter Count survival camp in Arizona holding a Helle fixed blade.

Winter Count tools: Tramontina machete and Mora knife with a beaded sheath—most popular knives at Winter Count.

But wait, I hear someone asking, “What about medium-sized blades, the ones in the six- to eight-inch range, the ones the military uses, the Randalls and KA-BARs and . . .” Well, that brings us to the next chapter, where we will deal with that question, plus another topic that bedevils many discussions among knife people: do we need thick, tough knives, or is a slim slicer with better cutting efficiently the best knife? The two questions are closely intertwined.