CHAPTER SIX

Blue-Water Victories

WHEN COMMODORE JOHN Rodgers spotted H.M.S. Belvidera on June 23 and began the first naval action of the war, he was operating far beyond the orders given to him by Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton, who had instructed Rodgers to remain close to New York with his squadron and await further orders. Even though war had been declared five days earlier, the president still had not decided how to employ his miniscule fleet.

During the first three weeks of June, Rodgers, expecting war to be declared, had waited in New York for specific orders. But none came. As the days passed, he grew more anxious, fearing a superior British fleet might sail down from Halifax, Nova Scotia, and trap his squadron in New York. The commodore had the President and her crew set to weigh the moment he received new orders from Washington. What he received instead was a letter from Secretary Hamilton warning that hostilities were likely (which Rodgers already knew) and urging, “For God’s sake get ready and let us strike a good blow.”

Rodgers didn’t need prodding; he had his men and ship well prepared. What he lacked was specific orders tied to an overall strategy. Being told to “strike a good blow” was not a substitute. Madison had known for months that hostilities were likely. Early in the year, he had held discussions with his advisors on how to deploy the fleet, but as war approached, he still had not settled on a strategy. Instead, he ordered what few warships were ready for sea to assemble in New York under Rodgers’s command and await further instructions. Rodgers was still waiting for them when, on Saturday, June 20, Revolutionary War hero Brigadier General Joseph Bloomfield, commander of the army in New York, told him that war had been declared. Early the next morning, a signal gun sounded from the President, alerting all officers and men to repair on board. Before long, the entire crew mustered on the big frigate’s weather deck. “Now lads,” the stern-faced Rodgers told them, “we have got something to do that will shake the rust from our jackets. War is declared! We shall have another dash at our old enemies. It is the very thing you have long wanted. The rascals have been bullying us these ten years, and I am glad the time is come at last when we can have satisfaction. If there are any among you who are unwilling to risk your lives with me, say so, and you shall be paid off and discharged. I’ll have no skulkers on board my ship, by God!”

Their patriotic instincts aroused, the crew greeted Rodgers’s words with spontaneous cheers. Every man declared his willingness to remain aboard and fight. As on all American warships, the crew was made up of a variety of men. Many were foreigners—often British citizens from Ireland. Some of the foreigners were naturalized Americans, but most were not. Those who had served in the British navy, whether they hailed from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, or England, were happy to be in the far more benign American service, even though they risked hanging if they were caught. The majority of Rodgers’s crew, however, were Americans, including a number of free African Americans.

Even though Rodgers could be a choleric taskmaster, his officers and crew respected him as an experienced leader who could bring them glory and prize money. Before joining the navy in 1798 during the Quasi-War with France, Rodgers had been in the merchant marine for eleven years, learning his trade and rising to become a captain, sailing out of Baltimore. President Adams appointed him to be second officer aboard the famed frigate Constellation, under Captain Thomas Truxtun. Rodgers was twenty-four years old and soon became the first lieutenant, playing a major role in the Constellation’s victory over the French frigate L’Insurgent, the most famous battle of the Quasi-War. He absorbed invaluable lessons from Truxtun in how to manage a warship. Rodgers was already a tough disciplinarian, but Truxtun, who was also a stern skipper, showed Rodgers how to avoid becoming a martinet. Truxtun believed that physical punishment should be used sparingly aboard an American man-of-war. Having to whip a man demonstrated the absence of leadership. Rodgers rarely administered a beating aboard the President.

After the Quasi-War with France, Rodgers played a leading role in the war against Tripoli. In June 1805 he brought an end to the conflict by threatening an all-out attack on the capital of Tripoli with a large American fleet. And two months later, Rodgers used his fleet to force a settlement on the ruler of Tunis. After the war Rodgers suffered through the navy’s lean years during Jefferson’s second term and Madison’s early presidency, remaining committed to the service and its high standards.

HEARTENED BY THE crew’s enthusiasm for getting to sea, Rodgers weighed anchor at 10 A.M. on June 21 and saluted New York. The 16-gun sloop of war Hornet, under Master Commandant James Lawrence, pulled her hook at the same time and saluted the city as well. The two ships then dropped down the Upper Bay with a fair wind, passed through the Narrows to the Lower Bay and then to Sandy Hook, arriving early in the afternoon. Waiting for them were three additional warships that had come up from Norfolk under thirty-three-year-old Commodore Stephen Decatur.

Secretary Hamilton had ordered Decatur to take what ships were available at the Norfolk naval base and join Rodgers in New York, but for what purpose the secretary did not say. Decatur could muster only his flagship, the 44-gun United States; the 36-gun Congress, under John Smith; and the 16-gun brig Argus, under Lieutenant Arthur Sinclair. At the same time, Hamilton had ordered Captain Isaac Hull, skipper of the Constitution—then refitting at the Washington Navy Yard—to join Rodgers as soon as possible and Captain David Porter, commander of the 32-gun Essex—undergoing repairs at the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn—to join Rodgers when his ship was ready.

Decatur had been anchored at Sandy Hook for two days, waiting impatiently for Rodgers. He wasn’t happy that Madison had decided to assemble all of the navy’s serviceable men-of-war in one place, risking entrapment or destruction by the Halifax squadron. Decatur had written to Hamilton on June 8 suggesting that instead of concentrating the navy’s few ships in one area, he should send them “out with as large a supply of provisions as they can carry, distant from our coast and singly, or no more than two frigates in company, without giving them any specific instructions as to place of cruising, but to rely on the enterprise of the officers.... If war takes place, it will . . . be of greatest importance to the country that we should receive our instruction and be sent out before the declaration shall be known to the enemy—it would no doubt draw from our coast in search of us, the greater part of their cruisers.”

Despite this advice, the president remained undecided about what to do with the navy, and his confusion was heightened by the fact that Rodgers was giving him markedly different counsel from Decatur’s. Rodgers thought the fleet should be kept together, not sent out singly. He envisioned his squadron attacking large convoys and scattered warships before the British knew a war was on. He thought that having a potent American fleet offshore would force the British to keep their Halifax squadron together, away from the coast, looking for the American fleet. This would allow the huge number of American merchantmen then at sea to return home safely. The Royal Navy did not have enough ships at their North American base to go after Rodgers’s squadron and at the same time blockade the coast.

The American navy’s principal target ought to be British commerce, Rodgers argued. He urged attacking the great merchant fleets sailing between the West Indies and England and those near the coasts of Britain itself, “menacing them in the very teeth, and effecting the destruction of their commerce in a manner the most perplexing to their government, and in a way the least expected by the nation generally, including those belonging to the Navy: the self styled Lords of the Ocean!!” Rodgers assured Hamilton that Britain’s home islands were poorly defended, that her huge fleets were deployed far from her shores.

At three o’clock on the afternoon of the twenty-first, while he was waiting off Sandy Hook, Rodgers received another message from Secretary Hamilton dated June 18: “I apprize you that war has been this day declared.... For the present it is desirable that with the force under your command you remain in such position as to enable you most conveniently to receive further, more extensive, and more particular orders, which will be conveyed to you through New York. But, as it is understood that there are one or more British cruisers on the coast in the vicinity of Sandy Hook, you are at your discretion free to strike them, returning immediately after into port.... Extend these orders to Commodore Decatur.”

The title of commodore was not a permanent rank in the navy; it was an honorary title assigned to the commander of a squadron. Rodgers was senior to Decatur and would be in command of the five- to seven-ship squadron assembling at New York. At age forty Rodgers was the navy’s second ranking officer. Fifty-seven-year-old Revolutionary War veteran Commodore Alexander Murray, commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard, was senior to him, but Murray was nearly deaf and considered too old for sea duty, which made Rogers the fleet’s senior officer in command.

Rodgers would have preferred more specific orders long before now, but he could not wait for them. His first priority was simply getting to sea, where he’d be safe from a blockade and where his location would be unknown. This would affect the calculations of Vice Admiral Herbert Sawyer, the British commander at Halifax—once he knew a war was on. Rodgers hoped Sawyer would not find out for a while and might have his men-of-war scattered, allowing the American squadron to pick them off in detail (one at a time). “We may be able to cripple and reduce their force,” Rodgers explained to Secretary Hamilton, “. . . to such an extent as to place our own upon a footing until their loss can be supplied by a reinforcement from England.”

WITHIN TEN MINUTES of receiving Hamilton’s latest message, Rodgers hoisted the signal to weigh anchor, and shortly thereafter the potent American squadron glided past the lighthouse on Sandy Hook and stood out into the Atlantic. If Rodgers remained at sea for any length of time, he would be acting contrary to Hamilton’s instructions. Nonetheless, he ignored his orders and set a course to intercept a huge Jamaica convoy of perhaps one hundred and ten merchantmen that regularly sailed during June and July from the Caribbean to England. Rodgers and Decatur agreed to split prize money evenly—a common practice.

The Jamaica convoy’s general route was well-known. Using the Gulf Stream and the prevailing southwesterly winds, the convoy would work up the Atlantic coast until it caught the westerlies north of Bermuda and use them to power it to England. The convoy would have escorts, of course. Since Parliament passed the Convoy Act in 1798, all British merchantmen were required to sail in protected convoys. But that didn’t faze Rodgers: His squadron would normally be much stronger than the men-of-war guarding the Jamaica convoy. If all went well, his fleet would capture or sink the escorting warships and then destroy or take much of the convoy as prizes. It would be the rousing start to the conflict that the administration hoped for but scarcely expected. And it would create a row in London; Parliament would want to know why the government had not anticipated war breaking out and positioned a squadron off New York to blockade Rodgers. At a minimum, disrupting the convoy would embarrass the Liverpool ministry.

WHILE RODGERS WAS putting out from New York, Secretary of the Treasury Gallatin wrote a hasty note to the president expressing concern that a significant percentage of the American merchant fleet—whose captains had no way of knowing war had been declared—were at sea and would be vulnerable to British attacks, particularly when they approached their home ports. Back on April 4, when Madison and Congress passed the ninety-day embargo on all shipments to Britain in order to pressure London, large numbers of American merchantmen put to sea before the law went into effect. Gallatin worried about the effect on the U.S. Treasury if it were deprived of the customs duties from these ships. He expected that “arrivals from foreign ports will for the coming four weeks average from one to one-and-a-half million dollars a week.” He considered it of the first importance that Madison direct the navy “to protect these and our coasting vessels, whilst the British have still an inferior force on our coasts.... I think orders to that effect, ordering them to cruise accordingly, ought to have been sent yesterday, and that, at all events, not one day longer ought to be lost. I will wait on you tomorrow at one o’clock.”

Gallatin had little difficulty convincing Madison, and on the following day, June 22, Hamilton wrote to Rodgers, ordering him to consider the returning American merchant fleet his first priority. To protect it, Rodgers was to take the President, Essex, John Adams, Hornet, and Nautilus on patrol from the Chesapeake Capes eastward, while Decatur patrolled from New York southward with the United States, the Congress, and the Argus. Hamilton expected the two squadrons to overlap somewhat, creating the possibility they might at times act in concert.

The orders appeared to be a compromise between Rodgers’s idea of a unified fleet and Decatur’s preference for a dispersed one, but they were actually based on Gallatin’s concerns and issued with little thought, since the president had no overall strategy. Fortunately, Rodgers did not receive Hamilton’s instructions for many weeks—after he returned from his cruise. If carried out, they would have left both squadrons so weak they would have been easy targets for the Halifax fleet. Neither Gallatin nor the president nor Hamilton, it would seem, considered that possibility.

AFTER HIS FRUSTRATING encounter with the Belvidera on June 23, Rodgers—with his broken leg in splints—continued hunting for the rich Jamaica convoy, repairing the President as he went. He had a good idea of where his prey was. Hours before running into the Belvidera, he had spoken with the American brig Indian Chief out of Madeira bound for New York. Her master reported that four days earlier he spotted a huge convoy—over a hundred ships, he thought—eastbound in latitude 36° north and longitude 67° west (just north of Bermuda). A frigate and a brig were escorting them.

Rodgers had no doubt that the ships the Indian Chief saw were the merchantmen he was after. The huge convoy had sailed from Negril Bay, Jamaica, on May 20 and passed the eastern tip of Cuba on June 4, guarded by the 36-gun frigate H.M.S. Thalia (Captain James Vashon) and the 18-gun sloop of war Reindeer (Captain Manners)—easy pickings for Rodgers. He estimated the convoy was only three hundred miles away.

ON JULY 3, while Rodgers was on the hunt, Captain David Porter put out to sea from New York in the restored Essex. The commandant of the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn, Captain Isaac Chauncey, had brought the old frigate up to a high state of readiness, careening her, cleaning and repairing the copper bottom, caulking her inside and out, putting on a false keel, and replacing all the masts. Although she had been launched thirteen long years ago in Salem, Massachusetts, during the Quasi-War with France, she was ready for combat, and so was her skipper.

As he passed Sandy Hook and drove into the Atlantic, Captain Porter was in high spirits. No British squadron was about, and the day before, he had received his promotion to captain—after an inordinately long wait, he thought. His orders, dated June 24, directed him to join Rodgers’s squadron, but it was nowhere in sight, and Porter was glad of it. He’d rather be on his own, free to conduct the hunt as he saw fit, without being under Rodgers’s thumb, having to share laurels and prize money.

If Porter failed to find Rodgers, his orders directed him to patrol between Bermuda and Newfoundland’s Grand Banks. Eight days out from Sandy Hook, on July 11, the Essex was in latitude 33° north and longitude 66° west—northeast of the Bermudas—when at two o’clock in the morning a lookout glimpsed the vague outlines of eight ships in the distance, running northward. Porter was out of bed and on deck in a hurry. He grabbed a telescope, and with the moon providing some hazy light, he counted seven troop transports, with a frigate as an escort. The vessels were spread apart in loose formation typical of convoys in which ships sailed at different speeds.

Porter decided to attack the rearmost vessel and cut her out in hopes of provoking a fight with the frigate. As the Essex closed in, the armed transport Samuel & Sarah—carrying 197 soldiers—did not attempt to escape. Porter had the weather gauge, and when he fired a single shot across her bow, she hauled down her colors. Her skipper assumed his escorting frigate, the 32-gun Minerva (Captain Richard Hawkins), would quickly engage the enemy.

By then it was 4 A.M., and, as expected, the Minerva broke away from the convoy and steered toward the Essex. Within a short time, however, she inexplicably came about and returned to the middle of the troop transports. Porter was puzzled. He was eager for a fight; the two frigates appeared evenly matched. He could not understand why Hawkins did not accept his challenge. Instead, the Minerva drew the remaining armed transports around her, so they could act in consort, and sailed on, daring Porter to approach.

Captain Hawkins’s orders were to transport the First Regiment of Royal Scots infantrymen from Barbados to Quebec and reinforce the small Canadian army. He probably judged it more important to accomplish his mission than to take on the Essex, although he must have wanted to. Except in extraordinary circumstances, no British captain would avoid fighting an American of equal strength. Doing so would earn him a court-martial and severe punishment.

With the odds now heavily against him, Porter decided it would be suicide to fight the entire convoy and settled for just taking the Samuel & Sarah. The number of men she had on board presented a problem, however. Porter did not want to be encumbered by so many prisoners. After throwing her armament overboard, he released the transport and all the soldiers on parole with a ransom bond of $14,000 and continued his cruise.

WHILE RODGERS AND Porter were off hunting in the mid-Atlantic, Commodore Philip B.V. Broke’s Halifax squadron arrived off Sandy Hook on July 14, only to discover that Rodgers’s fleet was gone and the Essex nowhere in sight. Broke’s task force was formidable; it consisted of his flagship, the 38-gun frigate Shannon, the 64-gun battleship Africa (Captain John Bastard), the 38-gun Guerriere (Captain James R. Dacres), the 32-gun Aeolus (Captain Lord James Townsend), and the 36-gun Belvidera—fully recovered from her run-in with Rodgers and still under Captain Richard Byron.

Two days later, Broke happened on the 12-gun American brig Nautilus, under Lieutenant William Crane, who had sailed out of New York on July 15, passing Sandy Hook at 6 P.M. with a fresh, squally wind out of the northeast. At 4 the following morning Crane was seventy-five miles off Sandy Hook when he spied Broke’s squadron two points off his weather beam. He immediately wore ship, “turned out the reefs and made all sail the vessel would bear.”

Crane was carrying yet more orders from Secretary Hamilton to Rodgers dated July 10. They read: “There will be a strong British force on our coast in a few days—be upon your guard—we are anxious for your safe return into port.” This was a far cry from Hamilton’s bombastic “strike a good blow” of a month earlier, when war had not actually been declared. When the declaration was made official on June 18, he toned down his aggressive talk and became more cautious. The new orders were apparently meant to keep the American fleet safe in New York and not have it out patrolling. Hamilton’s lack of consistency was for the most part caused by Madison’s continued indecision about naval strategy.

As soon as Broke spotted the Nautilus, he bore up and made all sail in chase, displaying American colors. A heavy swell from the north slowed the Nautilus and gave the bigger ships an edge. When Broke closed in, he made recognition signals that Crane did not understand. At the same time, Crane hoisted his own private signal and ensign, which Broke did not answer. Not that Crane expected him to; it had been clear from the beginning that this was a British squadron.

Crane was forced to take in sail to preserve spars, while Broke continued to gain. “Every maneuver in trimming ship was tried,” Crane reported, “but this not having the desired effect I ordered the anchors cut from the bows.” Nothing helped. “At nine o’clock the wind became lighter, and the brig labored excessively in the swell.”

With Broke closing in, Crane threw overboard part of his water, the lee guns, and a portion of his round shot. Instantly, the Nautilus was relieved and bore her sail with greater ease. But Broke continued to close. By 11 the Shannon had pulled within cannon shot, and for some unknown reason, Broke hoisted French colors but held his fire. Seeing no need to destroy the Nautilus, he kept pressing forward. At midnight he was within musket shot.

Knowing he could not escape, Crane destroyed his signal books and the dispatches for Rodgers. He then consulted his principal officers and decided to surrender. Crane took in the studding sails and light sails, trained the weather guns aft, and put the helm alee. Broke responded by putting the Shannon’s helm up, hoisting a broad pendant and British colors, and ranging up under the Nautilus’s lee quarter to accept Crane’s surrender.

In short order, the Shannon’s boats rowed over to take possession of the Nautilus . They returned later with Lieutenant Crane, who had a strained chat with his captor. Broke then put the officers and crew of the Nautilus in the battleship Africa, except for Crane, whom he sent back to the Nautilus as a lone prisoner with a British prize crew. The Nautilus was the first British capture of the war, and for the time being, Broke made her part of his squadron.

WHILE BROKE WAS corralling the Nautilus, Captain Isaac Hull was at sea in the newly refurbished Constitution, sailing from Chesapeake Bay to New York with orders to join Rodgers and Decatur. Hull departed the Chesapeake Capes on Sunday morning, July 12, with a fine southwesterly breeze, expecting to be off Sandy Hook within five days. His latest orders showed that the president and Secretary Hamilton were still confused about strategy. Rodgers had already left New York, which Hamilton had had time to learn, and he also knew a powerful British squadron was sailing down from Halifax to the New York area. Nonetheless, Hamilton ordered Hull to sail directly into the jaws of Broke’s fleet and certain disaster. “If . . . you fall in with an enemy vessel,” Hamilton wrote, “you will be guided in your proceedings by your own judgment, bearing in mind, however, that you are not voluntarily to encounter a force superior to your own. On your arrival at New York, you will report yourself to Commodore Rodgers. If he should not be in port, you will remain there till further orders.”

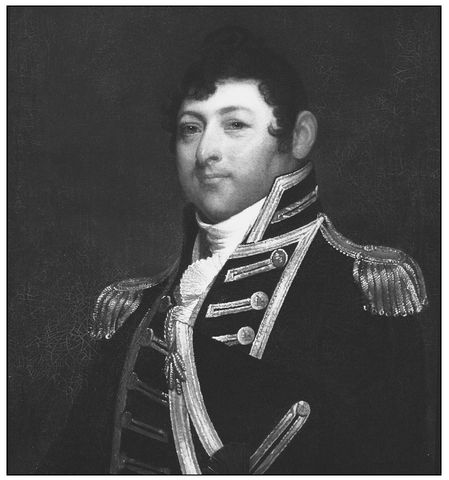

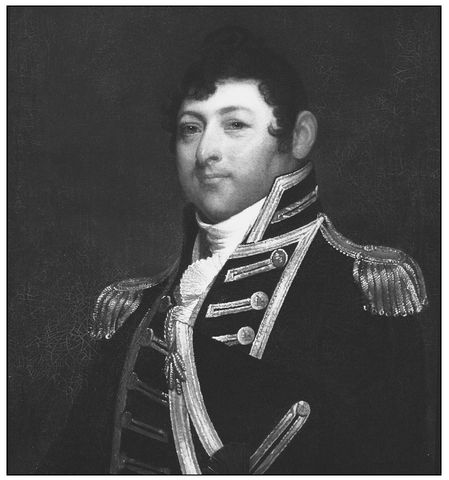

Figure 6.1: Samuel L. Waldo, Commodore Isaac Hull, USN (1773-1843) (courtesy of U.S. Naval Academy Museum).

This was the Constitution’s first cruise since April 5, when Hull had put into the Washington Navy Yard for extensive repairs. Of the navy’s six major shipyards, where men-of-war were built, fitted out, and repaired, the Washington yard was generally considered the best and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the worst. The others—New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Norfolk—were rated in between. Hull considered New York better because it was supervised by Captain Isaac Chauncey. By putting into the Washington Navy Yard, however, he wasn’t sacrificing anything. The superintendent, Commodore Thomas Tingey, had been in charge since the yard’s inception in January 1800, and he had established a solid record.

Hull had been skipper of the Constitution for two years, having taken command from John Rodgers on July 17, 1810. She was in poor condition then, not having had an extensive overhaul since 1803. Rodgers was leaving her because he wanted another ship, and, asserting his seniority, he had taken command of the President, which he considered the navy’s finest.

Luckily, Nathaniel “Jumping Billy” Haraden, who had been the Constitution’s master during the war with Tripoli, was at the Washington yard in April, and he worked with Hull and his officers seven days a week to get the aged ship into fighting condition. Much work needed to be done; her copper was in bad shape, and so were her upper works. She needed a complete suit of sails and new running rigging. Her hull and decks needed caulking, the ballast washed, and the hold cleaned out. By the time war was declared, however, the big frigate was ready for action.

The Constitution’s refurbishment exposed yet more ways in which the United States was unprepared for combat. Repairing and provisioning her had drawn down supplies and armament at the yard to a point where it could not serve the urgent needs of other warships and yards. Tingey was getting urgent requests from naval stations at Gosport, Wilmington, and Charleston for supplies, but he didn’t have them.

Although the Constitution was now in excellent shape, Hull needed to add to the crew. Enlistments in the American navy were typically for two years, which meant that able seamen left the ship at regular intervals. In wartime this presented a big problem. A majority of Hull’s crew had signed on when he took command from Rodgers in 1810. Many of them had departed at the end of their tour and now had to be replaced.

Hull even had trouble holding on to his talented first lieutenant, Charles Morris. When the Constitution put into Washington in April, Morris tried to obtain a command of his own, since that was the surest path to rapid promotion. He had already had a distinguished career. During Decatur’s famous attack and burning of the captured Philadelphia during the war with Tripoli, Midshipman Morris was the first man to board the unlucky frigate. Secretary Hamilton recognized Morris’s ability and was sympathetic, but in the end he ordered him back to the Constitution. Needless to say, Hull was happy to see him return.

On June 18 Hull sailed over to Annapolis to recruit crew members. Because of its proximity to Baltimore, where the war was popular, he thought recruitment would be easier than in thinly populated Washington. The Constitution departed Annapolis on July 5 with a full complement of four hundred forty men. Many of the newcomers had signed on in a fit of patriotic fervor. Not a few of them were green, however, and in need of training. Hull wrote to Hamilton, “The crew, you will readily conceive, must yet be unacquainted with a ship of war, as many of them have but lately joined us and never were in an armed ship before. We are doing all that we can to make them acquainted with [their] duty, and in a few days, we shall have nothing to fear from any single deck ship.”

In spite of having thirty men sick from dysentery and the various maladies prevalent during the bay’s unhealthy summers, Hull worked the crew hard. As he made his way up Chesapeake Bay, practice at the guns and the sails went on every day. By the time he passed the Chesapeake Capes and pushed out to sea, Hull was conducting gunnery practice twice a day and felt the crew was rounding into shape.

Five days after Hull entered the Atlantic, on July 17, a lookout at the main masthead spied four strange sails to the northward and in shore of the Constitution . They were definitely men-of-war. The wind was light, and thinking they were part of Rodgers’s squadron, Hull threw on all sail and steered toward them.

Around the same time, a lookout aboard H.M.S. Shannon saw a strange sail to the south and east standing to the northeast. He hollered down to the quarterdeck, where Broke soon had his telescope focused on the big ship in the distance. The Shannon was twelve miles east of Egg Harbor on the New Jersey coast. Broke had no doubt this was an American, and he gave the signal for a general chase. It was two o’clock in the afternoon. Broke’s squadron, in addition to the Shannon, included the 64-gun Africa and her tender, the 36-gun Belvidera, the 32-gun Aeolus, and the recently captured Nautilus with Lieutenant Crane still on board.

At four o’clock, one of Hull’s lookouts discovered another ship bearing northeast, standing for the Constitution with all her sail billowing. Hull thought she might be an American as well. For the next several hours the stranger sailed closer, but by sundown she was still too far away for her or the Constitution to distinguish recognition signals. The other four warships could only be seen from their tops.

Hull decided to steer toward the single ship and approach near enough to make the night signal. At ten o’clock he hoisted signal lights and kept them aloft for almost an hour, but got no answer. He now felt certain this ship, as well as the four inshore, were British, and he “hauled off to the southward and eastward” to escape. The ship he had been chasing raced after him, making signals to the others as she went.

At daylight, two frigates from the inshore group had pulled closer to the Constitution—one of them to within five or six miles, while the other four ships were ten or twelve miles astern. All were in vigorous pursuit with a fine breeze filling their sails. In the area where the Constitution was, however, the wind had died. The ship “would not steer,” Hull recorded, “but fell round off with her head” toward her pursuers. In desperation, Hull ordered boats hoisted out and sent ahead to tow the ship’s head round and get on some speed. By now three enemy frigates were five miles away, but they, too, had lost their wind and had their boats out towing.

With the enemy ships continuing to close, Hull ordered the men to quarters. He then ran “two of the guns on the gun deck . . . out at the cabin window for stern guns, and hoisted one of the twenty-four pounders off the gun deck, and ran that, with a forecastle gun, an eighteen pounder, out” the taffrail, where carpenters had cut away spaces. At seven o’clock Hull fired one stern gun at the nearest ship, but the ball splashed harmlessly into the water.

By eight o’clock four enemy ships were nearly within gunshot range and coming up methodically. The breeze was insignificant. Hull’s situation looked desperate. “It . . . appeared we must be taken,” he wrote. But, no matter the odds, he would not surrender. He intended to fire as many broadsides as he could and go down fighting. Before resorting to this grim measure, however, he accepted Charles Morris’s suggestion that they try using kedge anchors. That required warping the ship ahead by carrying out kedge anchors in the ship’s boats, dropping them, and warping the ship up to them. The ship was in only twenty-four fathoms of water—shallow enough. He ordered his men to gather three hundred to four hundred feet of rope and sent two big anchors out.

The kedging allowed the Constitution to gradually pull ahead, but the British saw what Hull was doing, and they began using kedge anchors themselves. The ships farthest behind sent their boats to tow and warp those nearest the Constitution . Soon they were again getting closer to Hull. At nine o’clock the nearest ship, the Belvidera, began firing her bow guns. Hull replied with the stern chasers from his cabin and the quarterdeck. The Belvidera’s balls fell short, but Hull thought a couple of his hit home because he could not see them strike the water. Soon, H.M.S. Guerriere (the single ship Hull’s lookout had spotted before) pulled close enough to unload a broadside, but her balls all fell short. She quickly ceased firing and resumed the chase.

For the next three hours all hands on the Constitution were at the backbreaking task of warping the ship ahead with the heavy kedge anchors. To lighten and trim the ship, Hull pumped 2,300 gallons of drinking water—out of a total of almost 40,000—overboard, and with the help of a light air he gained a bit on his hounds.

The British redoubled their efforts. At two o’clock in the afternoon all the boats from the battleship Africa and some from the frigates were sent to tow the Shannon. But as luck would have it, a providential breeze sprang up that enabled Hull to maintain his lead. The light wind stayed with the Constitution until eleven o’clock that night, and with her boats towing, she was able to keep ahead of the Shannon. Shortly after eleven, the Constitution caught a strengthening southerly wind that brought her abreast of her boats, which she hoisted up without losing any speed. Her pursuers were still near, but she was holding her own. To keep up, the Shannon abandoned her boats as the wind took her.

The ships sailed through the second night of their engagement with Hull maintaining his lead by employing every device he could think of. A portion of the log read: “At midnight moderate breeze and pleasant, took in the royal studding sails.... At 1 A.M. set the sky sails [they had just been installed at the Washington Navy Yard]. At [1:30] got a pull of the weather brace and set the lower [studding] sail. At 3 A.M. set the main topmast studding sail. At [4:15] hauled up to SE by S.” And so it went, as Hull, the great maestro, employed every instrument at his command.

At daylight on the nineteenth, six enemy ships were still visible. Hull now had to tack to the east, and in doing so, he passed close to the 32-gun Aeolus. The Constitution braced for a broadside, but the British frigate held her fire. Perhaps she feared becalming, “as the wind was light,” Hull speculated. In any event, after the Constitution passed, the Aeolus tacked and commenced her pursuit again.

At 9 A.M. an innocent American merchantman happened on the scene. The British ships instantly hoisted American colors to decoy her toward them. Hull responded by hoisting British colors. The merchantman’s skipper correctly assessed the situation, hauled his wind, and raced away.

As the day progressed, the wind increased, and the Constitution gained on her pursuers, lengthening her lead to as much as eight miles, but Broke kept after her—all through the day and night.

At daylight on the twentieth, only three pursuers were visible from the Constitution’s main masthead, the nearest being twelve miles astern. Hull set all hands to work wetting the sails, from the royals down, “with the engine and fire buckets, and we soon found that we left the enemy very fast,” Hull reported.

Commodore Broke recognized that even his lead ships were falling behind at an increasing rate, and at 8:15 he conceded the superior seamanship of the American and gave up the chase.

When Hull saw Broke hauling his wind and heading off to the north, he was enormously proud of his crew. They might have been green, but in a grueling, fifty-seven-hour chase, they had outsailed every one of Broke’s ships. It was an amazing display of seamanship, stamina, collaborative effort, and, indeed, patriotism. And especially so when one considers that Commodore Broke was among the best in the business. The Constitution’s crew had beaten Britain’s finest.

Having won this singular race in spectacular fashion, Hull now decided to make for Boston instead of New York, where his orders had directed him to go. He assumed Broke would be steering toward Sandy Hook to begin a blockade of New York, and he certainly did not want to run into him again.

After Hull’s incredible escape, the legend of his sailing prowess grew, and a story began circulating that during the Quasi-War with France, First Lieutenant Hull, then aboard the Constitution, had demonstrated that he was among the foremost sailing masters of his day. Britain and America had been quasi-allies against France at the time, and the Constitution’s skipper, Commodore Silas Talbot, had become engaged in a friendly race with the captain of the British frigate H.M.S. Santa Margaretta. The competition ran from sunup to sunset, with Hull serving as the Constitution’s sailing master. Long after the incident, James Fenimore Cooper wrote, “the manner in which the Constitution beat her companion out of the wind was not the least striking feature of this trial, and it must in great degree be subscribed to Hull, whose dexterity in handling a craft under her canvas was remarkable . . . he was perhaps one of the most skilful seamen of his time.” Needless to say, the Constitution won the race.

Inevitably, details were exaggerated: Hull was actually second lieutenant, not first, and this story was told to Cooper many years later by some surviving officers of the Constitution, including Hull. Even so, Hull’s prowess as a sailor was unquestionable. He might well have been the finest seaman in the American navy and perhaps in the world. In any event, Hull’s fledgling crew now had an esprit de corps that would have been the envy of any British captain.

WHILE HULL WAS eluding Broke, David Porter continued his cruise in the Essex. Two days after encountering the troop convoy, he captured the brig Lamprey, carrying rum from Jamaica to Halifax via Bermuda. He put a prize crew aboard and sent her into Baltimore to be condemned. Then, between July 26 and August 9, he took six more prizes. Two of them, the Hero and the Mary, he burned, as they were of little value; another, the Nancy, he ransomed for $14,000; and two others, the Leander and the King George, he sent into port as prizes.

On August 9 Porter seized his last prize, the brig Brothers. She had only recently been captured by Revolutionary War hero Joshua Barney in the privateer schooner Rossie. After seizing the Brothers, Barney had placed sixty-two prisoners aboard her—including men from five other vessels he had taken. Barney had then sent the Brothers on to St. John’s, Newfoundland, as a cartel vessel (a ship carrying only a signal gun whose sole purpose was to effect a prisoner exchange). Porter now added twenty-five prisoners of his own and sent all of them in the Brothers to St. John’s, under the charge of midshipman Stephen Decatur McKnight (Commodore Decatur’s nephew).

When McKnight arrived at St. John’s, the admiral in command, Sir John T. Duckworth, was none too happy. In making the Brothers a cartel vessel, Porter was attempting to affect an unorthodox prisoner exchange, which Duckworth protested in letters sent to Porter and to Secretary Hamilton. The admiral pointed out that by giving the Brothers a flag of truce and a proposal for an exchange of prisoners, she was insulated from possible recapture, while the Essex, without a diminished crew, could continue her rampage unencumbered.

As it turned out, the prisoners seized the Brothers from McKnight and put into another port on the island, but allowed McKnight to travel to St. John’s. When he met Admiral Duckworth, all he could do was hand him a list of names but no actual British prisoners. Nonetheless, Duckworth magnanimously acknowledged receipt of the British seamen and sent McKnight to Vice Admiral Sawyer, in Halifax, with a request that Sawyer see that McKnight got home, which Sawyer did. McKnight was saved from a dreadful incarceration aboard a prison ship in Halifax harbor. When he reached the United States, he rejoined the Essex.

Four days after sending the Brothers to St. John’s, Porter was on the quarterdeck at 9:30 A.M. when lookouts shouted down to him that a merchantman was in sight to windward. He extended his telescope and had a good look at her. She appeared to be an English West Indiaman. But the more he examined her, the more suspicious he got. “Every means had been used to give her that appearance,” he wrote. Suspecting she was really a warship in disguise, he quietly sent the crew to battle stations, while “concealing every appearance of preparation.” He kept the gun deck ports closed, the topgallant masts housed, and the sails set and trimmed in the careless manner of a merchantman. Since the Essex was small and lightly sparred, when her gun ports were closed, she looked—from a distance—more like a merchant vessel than a warship.

Porter was right about the stranger’s identity. The ship rushing toward him was the 18-gun British sloop of war Alert, under Thomas L. P. Laugharne. Either Laugharne was taken in by the Essex’s disguise, or in the finest British tradition—going back to Sir Francis Drake—he was defying the odds and continuing his mad dash toward the much larger frigate, bent on evening the odds by surprising her and hitting her hard before she knew what was up.

Porter held his fire and let Laugharne approach. By 11:30 the Alert was within short pistol shot, preparing to rake the Essex, when Porter suddenly ran up American colors and wore short around. While he did, the Alert unloaded a full broadside, which, Porter said, “did us no more injury than the cheers that accompanied it.”

The Essex’s larboard guns then exploded, carronades firing in unison, their heavy metal smashing into the Alert from point-blank range. Stunned by the broadside, Laugharne tried to escape, but Porter was on him, ranging up close on the sloop’s starboard quarter. As he came up, Porter hoisted a flag bearing the motto, “FREE TRADE AND SAILORS RIGHTS.” Another broadside or two at this distance would have been devastating, and so, with five men wounded, two guns disabled, the ship badly cut up and sinking, and his crew having deserted their stations and run below, Laugharne, according to Porter, “avoided the dreadful consequences that our broadside would in a few moments have produced by prudentially striking his colors.”

The entire action took eight minutes. Porter passed off the victory as a “trifling skirmish.” The only injury the Essex sustained was “having her cabin windows broken by the concussion of her own guns.” There was nothing trifling about the incident, however. It was the first time in the war that a British warship had struck her colors to an American. Both London and Washington had assumed the entire U. S. Navy would be crushed at the outset of the conflict, but Porter and his comrades were proving otherwise.

The triumphant Essex now headed home for a refit and to deal with the prisoners she had acquired. Eighty-six were from the Alert, raising the total number on board to a dangerous three hundred. Two days into the trip, in the middle of the night, eleven-year-old Midshipman David Farragut was lying half awake in his hammock—with other reefers, as midshipmen were then called, in the crowded steerage below the main deck—when out of a sleepy eye he glimpsed one of the prisoners standing beside him, gripping a pistol. The man was looking straight ahead into the darkness and not down at the hammock. Farragut froze and closed his eyes. A moment later, he slowly opened them. The man had disappeared. Without making a sound, Farragut rolled out of his hammock. Not seeing any more prisoners, he made his way through the darkened ship, slipped into the captain’s cabin, and awakened Porter, who, grasping the situation immediately, leapt to his feet and rushed on deck, shouting, “FIRE! FIRE!”

In a flash, the Essex men were out of their hammocks and rushing to their stations, as word was shouted around about the real crisis aboard. Part of Porter’s training was periodically sounding a fire alarm at night. Confused and frightened by the commotion, the prisoners meekly surrendered. Young Farragut was an instant hero.

The adventurous first cruise of the Essex was not over yet. On the way home to the Delaware River, Porter fell in with three powerful British warships off Georges Bank, northeast of Cape Cod. One was a brig-of-war in chase of an American merchantman. The other two were farther away and much bigger, probably frigates. Porter went after the brig, but the wind was light, and the brig had sweeps (long oars), which allowed her to escape.

After the Essex displayed American colors, the bigger warships sped after her. “At 4 P.M. they had gained our wake,” Porter reported. He kept on every sail, however, and managed to stay just beyond cannon range until dark, whereupon he hove about and steered straight for the largest pursuer, intending to either sneak past him or “fire a broadside into him and lay him on board.... The crew, in high spirits, . . . gave three cheers when the plan was proposed to them.” At 7:20 Porter hove about and stood southeast by south until 8:30, “when we bore away southwest without seeing anything more of them.”

Porter was unhappy he had not engaged one of the frigates and puzzled because a pistol aboard the Essex was accidentally fired at the time he calculated she was near the biggest enemy ship. He did make good his escape, however, and sailed for the Delaware River and home.

WHILE PORTER WAS making the most of his cruise, Commodore Rodgers and his squadron continued to search for the elusive Jamaica convoy. Thick fog plagued Rodgers, however. “At least 6 days out of 7 [were] so . . . obscure,” he wrote, that every vessel farther than four or five miles away was invisible. At times “the fog was so thick... it prevented us seeing each other, even at a cable’s length” (two hundred yards). On June 29 Rodgers spoke an American schooner from Teneriffe. The master said he had passed the convoy two days before, one hundred and fifty miles to the northeast. Rodgers set all sail in that direction, and on July 1 he saw garbage strewn over the water, “quantities of cocoa nut shells, orange peels &c &c,” indicating “the convoy was not too far distant, and we pursued it with zeal.”

During the next three days Rodgers captured two enemy ships, the brigs Tionella and the Dutchess of Portland, and burned them, but the convoy was nowhere in sight. On July 9, he captured the 10-gun privateer, Dolphin, north of the Azores, and sent her into Philadelphia under a prize master. On the same day, the Hornet captured a British privateer in latitude 45° 30’ north, and longitude 23° west. Her master reported seeing the convoy the evening before. Rodgers continued the chase, sailing east toward the English Channel. On July 13 his squadron was a day’s sail from the chops of the Channel when he abruptly changed course and stood south toward Madeira. He had decided to cut short the cruise and head back to Boston. Scurvy had broken out aboard the United States and the Congress. They had a troubling number of cases—perhaps as many as eighty—between them. No scurvy appeared aboard the President, however.

Rodgers was off Madeira on the twenty-first, and on the twenty-fourth, northwest of the Canaries, he captured the 16-gun letter of marque John, which he sent to the United States as a prize. He sailed next to the Azores, and from there to Newfoundland’s Grand Banks and then to Cape Sable, before setting a course for Boston, sorely disappointed at the lack of action. Returning to New York would have been too risky; Boston was much less likely to be blockaded. On the way, Rodgers captured four more vessels. For the entire voyage, however, he took only nine stray British merchantmen and privateers, and recaptured an American vessel—little enough, given his efforts and the high hopes he had originally entertained for the squadron.