CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

Burning Washington

COMMODORES RODGERS AND Porter, as well as Oliver Hazard Perry, were available in the summer of 1814 to help defend against Vice Admiral Cochrane’s east coast raids. It had been obvious for some time that Cochrane would concentrate on the Chesapeake Bay area, since it contained both the capital and Baltimore, the city with the largest and most bothersome privateer fleet. New York and Philadelphia were much harder to get at, and the ports of Federalist New England seemed even less likely targets. Secretary Jones positioned Rodgers, Porter, and Perry so that they could help defend whatever city Cochrane struck.

On April 4, Rear Admiral Cockburn began operations in Chesapeake Bay by establishing a forward base on Tangier Island, where he could receive escaped slaves and spread the news to others that a secure retreat awaited them. Alerted by friends, runaways watched for British barges rowing up rivers and creeks at night. Lighted candles signaled that boats were ready to take men, women, and children to safety. They came by the dozens and then the hundreds to an uncertain future. Anything was better than the hell they were experiencing, however. Cockburn’s operation was so successful that as early as the middle of June he was employing former slaves as soldiers in the small-scale, hit-and-run raids he had resumed.

Situated ten miles southeast of the Potomac, Tangier Island was also an ideal base from which to attack Washington, Annapolis, and Baltimore. Cockburn could keep an eye on Joshua Barney’s flotilla from there as well. Before attacking any of the major cities, Cockburn first had to deal with Barney. Small though they were, Barney’s row galleys were the only naval force challenging the British in the bay.

On April 26 Barney was promoted to the rank of captain in the American Flotilla Service. He had been building his fleet in Baltimore all winter. It wasn’t easy. Money was tight, as were men and resources, but by the third week in May, Barney had thirteen specially constructed galleys ready with one twelve-pounder in their bows and a single powerful carronade mounted in the stern. Each was powered primarily with oars. He also had a gunboat, a smaller galley, another smaller boat for surveillance, and the 5-gun cutter Scorpion, commanded by William Barney, his eldest son. The Scorpion was Barney’s flagship. The schooner Asp joined him later.

On May 24, Barney set out with his fleet for a surprise attack on Tangier Island. A few courageous merchantmen, who wanted to get to the Atlantic, accompanied him. After leaving Baltimore, they stopped at the Patuxent River and then sailed south on June 1. At nine o’clock in the morning, they ran into a strong British squadron that included the 74-gun Dragon, under Captain Robert Barrie; the 13-gun armed schooner St. Lawrence, under Commander David Boyd; and a number of smaller boats. For a brief time the Dragon was separated from the others, which gave Barney an opportunity to attack the rest of the squadron, but he missed it, and when the Dragon reappeared he retreated in a big hurry to the Patuxent, twenty-five miles north of the Potomac and sixty miles south of Baltimore. Shots were exchanged at the mouth of the river near Cedar Point, but adverse weather and general fatigue made further fighting too difficult, and both sides pulled back. The Patuxent was a safe refuge for Barney’s flotilla. His shallow draft vessels could travel forty miles upriver beyond Pig Point, where low water levels protected them from all British warships. Smaller enemy barges could get at the flotilla, but Barney was confident he could deal with them.

After the fight at Cedar Point, Cockburn went after Barney in earnest. He reinforced Barrie’s Dragon and St. Lawrence with the 50-gun razee Loire, under Captain Thomas Brown; the 18-gun brig-sloop Jaseur, under Commander George E. Watts; and more barges. Barney responded by moving his flotilla farther up the Patuxent.

On June 8 and 9, all of Barrie’s larger ships, except the Dragon, sailed up the Patuxent with fifteen barges. Barney drew back into St. Leonard’s Creek for protection, where the barges attacked him. They began firing Congreve rockets at eight o’clock in the morning on June 9. The projectiles screeched as they flew at the Americans, but they all missed and did no damage. The small missiles were only good for frightening an opponent. Barney rowed his undamaged barges forward, firing twelve pounders, forcing the enemy barges to retreat back to the larger ships. When they did, he withdrew up the creek.

On June 10 Barrie made a more determined attack, but Barney stood firm, and the British retreated again. This time Barney pursued them down the creek, attacking fiercely, driving them back. The ferocity of his attack took the St. Lawrence, which was at the mouth of the creek, off guard, and in the ensuing melee she ran aground. Barney continued his assault, cutting up the stranded schooner and nearly capturing her before the larger ships, which were also taken by surprise, came to the rescue and forced Barney to retire. The battle lasted six grueling hours.

On June 26, after careful preparation, Barney attacked the larger warships blockading him in St. Leonard’s Creek. He was supported this time by a battery firing from elevated ground at the mouth of the creek. His combined land and sea barrage forced Captain Brown to withdraw the Loire farther down the Patuxent. When he did, Barney escaped from the creek and rowed north up the Patuxent to safety above Pig Point.

BARNEY’S FLOTILLA WAS still secure in the Patuxent when, on July 24, forty-seven-year-old Major General Robert Ross arrived at Bermuda with 3,500 battletested veterans of Wellington’s army in France, men who thought they’d be going home after defeating Napoleon. Instead, they were confined in the bowels of troop transports for a long, uncomfortable voyage. They were supplemented by 1,000 marines, bringing Ross’s army to a total of 4,500 men.

Ross was expected to work closely with Admiral Cochrane to conduct large-scale raids along the American coast. Cochrane would decide where the raids were made, but Ross would command on the ground and have a veto if he disagreed about the places or timing of the raids. The Admiralty cautioned Cochrane not to advance his modest army “so far into the country as to risk its power of retreating to its embarkation.”

According to Lord Bathurst the overall purpose of the raids was to “effect a diversion on the coast of the United States . . . in favor of the army employed in the defense of Upper and Lower Canada,” but Cochrane intended to do more than simply create a diversion. He wanted to punish Americans for the atrocities they had committed along the Canadian frontier. Colonel Campbell’s depredations at Long Point in May had so infuriated Governor-General Prevost that on June 2 he had asked Cochrane to “assist in inflicting that measure of retaliation which shall deter the enemy from a repetition of similar outrages.” Cochrane was only too happy to comply. On July 18 he ordered his commanders “to destroy and lay waste such towns and districts upon the coast as you may find assailable. You will hold strictly in view the conduct of the American army towards His Majesty’s unoffending Canadian subjects, and you will spare the lives merely of the unarmed inhabitants of the United States.” Cochrane and Prevost ignored British massacres and depredations against American soldiers and civilians, acting as if only the United States savaged civilians.

Over a month later Cochrane sent a copy of his order to Secretary of State Monroe, who wrote back the first week of September, explaining that any acts of destruction or outrages committed by American troops were not sanctioned by the government, as Cochrane charged, and those responsible were disciplined. Cochrane was not interested in winning an argument, however; he intended to carry out a course of destruction no matter what, since it was what his government wanted and, indeed, what his countrymen wanted.

Although Cochrane told Prevost months before that he would be conducting raids in Chesapeake Bay, by August he had doubts about the timing. The heat, humidity, and generally unhealthy climate during the summer made it the worst time for an attack on Washington. Cochrane preferred October, when the weather was milder and the climate not so sickly. He also had to think about New Orleans. The battles in the Chesapeake, however important, were only diversions. New Orleans was a far more important objective, and it would take time to gather the forces for the invasion.

On the other hand, Cochrane yearned to hurl Mr. Madison “from his throne.” He was also impressed with the psychological importance of taking the capital and of how easy it would be right then. Rear Admiral Cockburn had been urging Cochrane to attack right away. “It is quite impossible for any country to be in a more unfit state for war than this now is,” he wrote to his chief, “and I much doubt if the American Government knew . . . every particular of the intended attack on them, whether it would be possible for them to . . . avert the blow.” In another letter, written the same day, Cockburn boasted, “within forty-eight hours after the arrival in the Patuxent of such a force as you expect, the city of Washington might be possessed without difficulty or opposition of any kind.”

In spite of Cockburn’s assurances, Cochrane and Ross remained uncomfortable with the timing of an attack on Washington. They left Bermuda on August 1 in Cochrane’s flagship, the 80-gun Tonnant, and sailed for Chesapeake Bay to confer with Cockburn. A flotilla of troop transports and warships, under Rear Admiral Pulteney Malcolm, left Bermuda two days later, arriving at the Virginia Capes on the fourteenth, after six hundred often difficult miles, discomforting the long-suffering soldiers even more.

President Madison was convinced that Washington would be Admiral Cochrane’s primary target. Secretary of State Monroe agreed with him. At one time Monroe entertained the idea that the British would be so tied down in Europe dealing with the aftermath of the war that they would not invade the United States at all, but when he saw them building up their forces in North America, he became convinced that Washington was in mortal danger. Secretary Jones thought that the British might attack Washington but that Baltimore or even Annapolis was a more likely target. Secretary Armstrong was fanatical in his belief that only Baltimore would be attacked.

Madison, however, was certain the British would aim at the seat of government. Attorney General Rush reported that the president thought Washington would be an inviting target because of “the éclat that would attend a successful inroad upon the capital.” As apprehensive as the president undoubtedly was, it is difficult to explain why he hadn’t strengthened the capital’s defenses much earlier in the war. Madison thought a force of around 13,000, including 500 of Barney’s sailors, would be sufficient to defend the capital, and he believed they could be obtained from the militias of the District of Columbia and the surrounding states of Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Secretary Armstrong was in charge of the capital’s defense, but he remained unshakable in his conviction that the British would not attack there, and he did nothing to prepare. Madison was well acquainted with the secretary’s views and actions, but still he did not replace him.

To strengthen Washington’s defense, Madison on July 1 created the tenth military district, which included the capital, Maryland, and parts of Virginia. And he put thirty-nine-year-old Brigadier General William Winder in command. It is difficult to explain why Winder was appointed. He had been one of the key figures responsible for the defeat at the important Battle of Stoney Creek on the Niagara Peninsula the previous year. That action stopped the progress Dearborn and Chauncey were making against Upper Canada.

Winder had been captured and removed to Quebec with the rest of the prisoners. He was then released to go to Washington and arrange a prisoner exchange, which he did, concluding a convention on April 16, 1814. He was the nephew of the antiwar Federalist governor of Maryland, Levin Winder, and that may be why the president appointed him.

Madison may have thought that having the governor’s nephew in command would make calling out the Maryland militia easier. Whatever the president’s reasoning, it was a baffling appointment. To make matters worse, the inscrutable Armstrong opposed Winder’s selection and refused to work with him.

Winder’s recruitment problems were daunting. Only 500 regulars were in the Tenth District. Primary reliance had to be on militiamen. Although 93,500 had been placed on alert, Winder had no authority to call them out until there was imminent danger. On July 12, he received permission to call up 6,000 from Maryland, but in the next six weeks his uncle managed to produce only 250. Even when called up, the militiamen were not under Winder’s command until the War Department organized and equipped them and turned them over to him. On July 17 Winder was allowed to call up 7,000 more from Pennsylvania, 2,000 from Virginia, and 2,000 from the District of Columbia, but fewer than 1,000 appeared. It turned out that because of changes in state law, Pennsylvania could not send any.

Armstrong was indifferent to Winder’s problems. The secretary was constantly complaining about the lack of money, absolving himself of any shortcomings, and placing the blame for whatever happened on the president and Congress. Avoiding responsibility was an old habit of Armstrong’s.

The secretary’s gross insubordination continued unabated throughout the crisis. He gave no direction to Winder, who had no idea how to proceed. The hapless general spent an inordinate amount of time simply reconnoitering the area under his supervision without doing anything to erect defenses along the major invasion routes to the capital. The first and most likely was through Bladensburg; another was through Old Fields to the Eastern Branch bridge, a mile from the Washington Navy Yard. Yet another was by way of the Potomac. That was the least likely: the river itself presented too many obstacles to navigation. And it was defended at a strategic point by Fort Washington on the Maryland side of the river, opposite Mount Vernon. Winder made no attempt to fortify Bladensburg or to strengthen Fort Washington.

ON AUGUST 14 General Ross and Admiral Cochrane arrived at the mouth of the Potomac in the Tonnant for talks with Rear Admiral Cockburn. They still entertained doubts about the wisdom of attacking Washington right then. The weather was a problem, as was the condition of the troops after their long voyages. Also, using 4,500 tired regulars to attack the capital of a nation of nearly 8 million would seem at first glance a harebrained scheme. Cockburn, however, was absolutely confident, as he always was, and he removed their doubts. They agreed to land the troops at Benedict, Maryland, on the Patuxent, and march them along the west bank to Lower Marlboro and then Nottingham. At the same time, Cockburn would ascend the river with his squadron on Ross’s flank, carrying supplies. Their immediate objective was the destruction of Barney’s flotilla. Once that was accomplished, a final decision could be made about Washington.

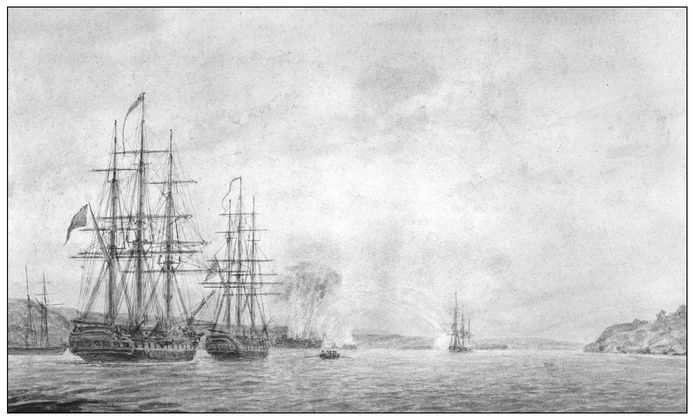

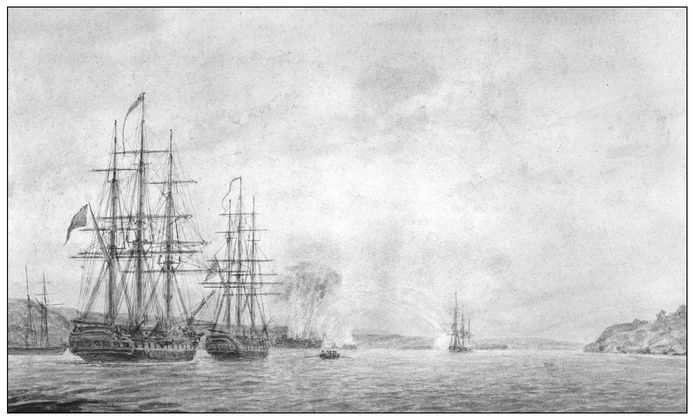

Figure 24.1: Irwin Bevan, Attack on Fort Washington on Potomac, 17 August 1814 (courtesy of Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia).

On August 17, Cochrane ordered Captain James A. Gordon to sail up the Potomac with a powerful squadron, draw attention away from Ross’s landing, and assist him as a rear guard. Beside his own 38-gun frigate Seahorse, Gordon had the 36-gun Euryalus, under Captain Charles Napier; the bomb vessels Devastation (Captain Alexander), Aetna (Captain Kenah), and Meteor (Captain Roberts); the rocket ship Erebus (Captain Bartholomew); the schooner Anna Maria (a tender); and a dispatch boat. The Potomac was extremely difficult for larger ships to ascend, which is one of the reasons Secretary Jones thought it unlikely the British would attempt it. Gordon, who had the temporary rank of commodore and was one of the senior—and most accomplished—captains in the Royal Navy, expected the river and Fort Washington to give him plenty of trouble.

As a further distraction in favor of Ross, Cochrane sent Captain Sir Peter Parker to create havoc farther up the Chesapeake above Baltimore with a squadron that included the 36-gun Menelaus and some smaller vessels. Cochrane then proceeded with the remainder of his naval force to the mouth of the Patuxent and landed Ross and his army on August 19 and 20 at Benedict, forty-five miles from Washington. The town was practically empty; the townspeople had fled. Ross had one six-pounder and two three-pounders. Attacking the American capital with only 4,500 troops might have seemed imprudent to Ross earlier, but now the utter lack of opposition impelled him forward.

WHEN GENERAL WINDER and President Madison heard about the landing at Benedict, they ordered obstructions put in the way of the invaders, but nothing happened. Winder also called out the militia. Armstrong had refused to let him call them out ahead of time, but now a crisis demanded it. The militiamen began gathering, and Winder soon had 2,000 camped ten miles southeast of the capital.

Unaware that Ross had actually landed, Secretary Jones wrote to Commodore Rodgers in Philadelphia on August 19: “The enemy has entered the Patuxent with a very large force, indicating a design upon this place, which may be real or it may serve to mask his design upon Baltimore.” Since Jones thought Baltimore the more likely target, he ordered Rodgers to march there with three hundred men and combine them with the detachment of marines at nearby Cecil Furnace. Jones sent similar instructions to Commodore Porter in New York. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry was already at Baltimore supervising construction of the new frigate Java.

HAVING DEBARKED HIS troops, Ross now marched—again unopposed—to Lower Marlboro and then to Nottingham on August 21, while the British squadron under Rear Admiral Cockburn made its way up the Patuxent on Ross’s right flank toward Barney’s flotilla. Barney knew they were coming. He had already put five heavy cannon (two eighteen-pounders and three twelve-pounders) on carriages and marched with them and four hundred men to Upper Marlboro and from there on the twenty-first to the Washington Navy Yard. A few of Barney’s men remained with the flotilla, ready to set it on fire when Cockburn approached. The night of the twenty-second, when Cockburn’s boats and marines appeared, Barney’s men burned the flotilla and fled.

On the same day, August 22, Ross resumed his march and easily reached Upper Marlboro. No obstacles were in his path nor any resistance. He was now only fifteen miles from Washington, and being that close and having encountered no opposition, he decided—with Cockburn urging him on—to push on toward the capital.

Cockburn received a note from Cochrane congratulating him on the destruction of Barney’s flotilla. Cochrane added, however, that “the sooner the army gets back the better.” This was not an explicit order to return immediately, but it might have been read that way. The aggressive Cockburn chose to ignore its implications, however, and proceeded with the attack on Washington.

General Winder, in the meantime, had succeeded in gathering 2,000 militiamen at Battalion Old Fields, not far from Upper Marlboro and Ross’s army. Barney and his men were with him. The president and his cabinet visited there on the twenty-second and conferred with Winder, stayed overnight, and returned to Washington the next day.

Ross put his troops back in motion the evening of the twenty-third. The heat and humidity, combined with the weak condition of the men, caused many to fall by the wayside from exhaustion and disease, forcing him to stop for the night after advancing only five miles.

For some unexplained reason, that same day, Winder, not knowing Ross’s ultimate destination, marched his troops back to Washington, crossing the lower, or Eastern Branch bridge, into the city a mile from the navy yard. People were terrified. They thought the British had pushed Winder back. Barney and his men were still with him, and they remained through the night.

That same day, August 23, Baltimore militiamen, under Brigadier General Tobias Stansbury and Colonel Joseph Sterrett, numbering approximately 2,000, arrived at Bladensburg. The small town was at a crossing point on the Eastern Branch of the Potomac seven miles from Washington. Winder had ordered Stansbury to position his troops between Ross’s army and the town. Stansbury wisely ignored the order, and on the morning of August 24 he marched his men through the town, crossed the wooden bridge (Stoddert’s bridge) to the west side of the Eastern Branch, and took up a defensive position on the high ground overlooking the bridge and the shallow ford nearby. Stansbury ordered the bridge destroyed, but for some unknown reason it remained standing.

That same morning, Ross marched his army to Bladensburg, arriving at noon. Winder, meanwhile, having guessed wrong about what road Ross was taking to Washington, had his men guarding the Eastern Branch bridge six miles away. Incredibly, Winder at no time had intelligence of Ross’s movements.

While Ross was marching to Bladensburg, the president and his advisors were conferring with Winder at the Washington Navy Yard. It was ten o’clock. Suddenly, word came that the British were on the road to Bladensburg. Monroe raced to the town, while Winder set his troops in motion and galloped off to Bladensburg himself, leaving Barney to defend the Eastern Branch bridge and to blow it up if necessary. The president followed Winder, but before he left, Barney asked him if he could march his flotilla men to the battlefield as well. Only a few were needed to blow up the Eastern Branch bridge, Barney argued. He was needed far more at Bladensburg. Madison agreed, and Barney set out for the battlefield, arriving with five heavy cannon and five hundred men. He was forced to set up a half mile from the bridge, well back of Stansbury’s men. Barney arranged his big naval guns to cover the road to Washington.

WHEN ROSS REACHED Bladensburg, Winder’s militiamen were well positioned on commanding heights on the other side of the river. Ross estimated there were between 8,000 and 9,000. Actually, there were fewer than 6,000. In spite of the enemy’s numbers and the fatigue of his men, Ross attacked immediately. He began by firing Congreve rockets, and as they screamed overhead, the first of the British light infantry, led by Colonel William Thornton, rushed across the bridge under heavy fire. They were stymied by the heavy outpouring coming from cannon and muskets, however, and had to withdraw back across the bridge. But they attacked again, and the second wave, with Ross in their midst urging them on, managed to cross; more followed, and then even more.

President Madison was on the battlefield and withdrew with his party when the first rockets screeched overhead. There was a report that he was nearly captured, but this was not the case. As the president was leaving, disorder had already begun spreading among the inexperienced militiamen. A short while later, they began retreating in earnest, fleeing in all directions. But Barney and his five hundred sailors and marines with their heavy guns held firm, and militiamen from Maryland and Washington to Barney’s left and right stood with them, halting the British advance.

Barney’s guns and the militiamen beside him were the last line of defense—all that stood between Ross and Washington. The British continued their attack, with Barney’s crew and the nearby militiamen desperately holding them off. The militiamen near Barney were under heavy fire when Winder rode up and inexplicably ordered them to fall back, which they did, and then fled like the others, leaving Barney and his seamen alone. They continued firing at the enemy. Barney’s horse was shot out from under him, but he got up and continued to fight. A musket ball then struck him in the thigh, and he lay on the ground bleeding. With the British closing in, he ordered a retreat, which his men reluctantly carried out.

Barney could not go with them. He had collapsed in a pool of blood and was soon captured, as the British swarmed around. Admiral Cockburn and General Ross were directed to his side. When Barney saw them, he looked up with a grin, “Well admiral, you have got hold of me at last.” Cockburn and Ross had an English surgeon tend to him right away and may have saved his life. They could not have been more solicitous. Ross promptly freed Barney and his officers on parole. He had Barney taken to Ross’s Tavern in Bladensburg, where he’d be comfortable. Barney later said he was treated “as if I was a brother.”

The one-sided battle was over by four o’clock. Of Ross’s men, 64 were dead and 185 wounded. There were 71 American casualties, most of them Barney’s flotilla men. During the entire crisis the enigmatic Armstrong had acted as if he were a spectator, offering no direction to Winder or advice to the president. He performed as he had the previous year during the abortive attack on Montreal, when, sensing disaster, he sought to place all the blame for it on Wilkinson and Hampton. Now he kept his head down, seeking to put all the onus for the debacle on Winder and Madison.

An hour earlier, just after three o’clock, Dolley Madison left the presidential mansion in a wagon with plates and portable articles, including George Washington’s portrait. She crossed the Potomac on the Little Falls Bridge and made her way to Rokeby plantation in Loudoun County, Virginia, the home of Richard Love, where she would spend the night with her close friend Mrs. Love.

The day before, the president had warned her to be prepare to leave Washington at a moment’s notice. He had told her to take care of herself and the papers, public and private, in the president’s house. At the same time, he had ordered important papers from all government offices removed. Many of the documents dated back to the Revolution, including the Declaration of Independence and the papers and correspondence of George Washington.

Shortly after Dolley’s departure, Madison himself reached the Potomac and crossed over to Virginia at Mason’s Ferry. He would spend the night at Salona, the home of Reverend John Maffitt. The following day he and Dolley were reunited at Willey’s Tavern, where she remained until the British left Washington.

AFTER THE BATTLE, Ross rested his men only two hours before marching them seven miles unopposed to the capital. Cockburn, who, as might be imagined, was exhilarated, went with them. He and Ross rode white horses, and even though it was eight o’clock and Washington was dark, they were conspicuous. As they entered the city, three hundred men from behind buildings next to Albert Gallatin’s house opened fire, killing Ross’s horse. The militiamen were quickly dispersed, however, and the British proceeded to burn the capital’s public buildings and a few private ones.

Ross and Cockburn entered the White House, or President’s House as it was then called, and found plenty of good wine to toast the Prince Regent before setting the place on fire. The Capitol and the Library of Congress were also burned, as was the building housing the National Intelligencer, which Cockburn personally attended to, since its editor, Joseph Gales Jr., was a persistent critic of his. Gales was surprised to learn that Cockburn was reading his newspaper. The August 24 edition had expressed complete confidence that Washington was safe.

The British later excused the wanton destruction of the capital by claiming it was done in retaliation for the burning and plundering that American troops did in Canada. Nothing the United States did in Canada, however, remotely justified the burning of Washington.

WHEN THE BRITISH entered the city, Commodore Tingey, under strict orders from Secretary Jones, destroyed the Washington Navy Yard. Tingey delegated the baleful task to Master Commandant John O. Creighton, and he carried out his duty with a heavy heart, burning the new frigate Columbia and the new sloop of war Argus. When Creighton and his crew were finished, the only building left standing was the marine commandant’s red-brick house.

The British rampage through the city continued into the next day. It only came to an end when a severe hurricane struck, tearing off roofs, destroying buildings, and dousing fires. During the unexpected tempest, flying debris and collapsing houses killed thirty British soldiers. Ross and Cockburn had already decided to retreat to their ships. Since their attack was only a diversion, it seemed prudent to leave as quickly as possible.

When news of Washington’s destruction reached London on September 27, Lord Bathurst, although delighted, was critical of how compassionately General Ross had treated the people of the city. “If . . . you should attack Baltimore, and could . . . make its inhabitants feel a little more of the effects of your visit than what has been experienced at Washington,” he wrote, “you would make that portion of the American people experience the consequences of war who have most contributed to its existence.”

On August 25, under cover of darkness, Ross and Cochrane pulled out of Washington and marched back to Benedict via Upper Marlboro and Nottingham. Ross thought it possible that American militias might turn out in overpowering numbers, bent on revenge. He encountered no opposition, however, and on the evening of August 29 his weary men boarded their transports. Ross was immensely proud of their work. He was particularly delighted with the abundant cannon, powder, and musket cartridges they had hauled away.

General Winder, meanwhile, after the debacle at Bladensburg, gathered what men he could and retreated to Montgomery Court House (Rockville), sixteen miles from Washington, and then moved on to Baltimore, where he thought the next attack would occur.

THE PRESIDENT, AFTER fleeing the capital on August 24 and meeting Dolley the next day, turned around and returned to Washington with some cabinet members on August 27. General Ross had retreated much faster than Madison expected. The president stayed in Washington at the house of his brother-in-law Richard Cutts, which had once been his own home, and Dolley rejoined him there. She had shown remarkable courage throughout the crisis. Later, she and the president took up residence in Colonel John Tayloe’s large residence, known as the Octagon House. (Tayloe was a wealthy Virginia planter, perhaps the richest in the state.)

Madison’s character shone in the aftermath of the debacle. He remained steady and kept firm control of the government, providing essential leadership and demonstrating that Washington may have been burned but the United States was very much intact. And he finally rid himself of Armstrong, replacing him with Monroe for the time being. It was abundantly clear that Armstrong could no longer lead the army, having worn out his welcome with everyone. On September 1, wanting to demonstrate that he was in charge of a functioning government, Madison issued a proclamation urging Americans to expel the invader and accusing the British of “a deliberate disregard of the principles of humanity and the rules of civilized warfare.”

CAPTAIN JAMES GORDON, meanwhile, continued to doggedly lead his squadron up the Potomac. Starting on August 17, he had pushed upriver, encountering no opposition. He kept at it for ten days, overcoming every natural obstacle, including a hurricane on the ninth day—the same storm that hit Washington. He warped his big ships over shallow waters, grounding continuously on shoals while fighting adverse winds. He reported that every one of his larger vessels had gone aground twenty times and were only gotten off by a prodigious effort. Nonetheless, he persevered. He did not reach Fort Washington until the evening of August 27, the same day that Madison returned to the capital.

The fort had a battery of twenty-seven guns, ranging in size from six to fifty-two pounders, and sixty men. Armstrong had not bothered to strengthen it, nor had the president. The pathetic number of men and guns could never withstand Gordon. When he commenced firing from the bomb vessels, he expected a fierce response, but to his utter amazement, none came. The bombardment went on for two hours, before Captain Samuel Dyson and his men fled from the fort and blew it up without firing a shot. Dyson was soon dismissed from the army. The entire blame for the fiasco was placed on him, not on the secretary of war and the president, where it belonged.

Alexandria now lay open to Gordon, and he stood off its wharves on the morning of August 29. The town was defenseless. Its militiamen, who had participated in the fiasco at Bladensburg, were nowhere to be found. Alexandria’s leaders had pleaded with the administration to give them cannon and other munitions, and they were promised them, but none were delivered. There was nothing left to do now but throw themselves on Gordon’s mercy. He made a deal to spare the town in return for supplies and prize ships—twenty-one of them, stuffed with tobacco, wine, sugar, and other goods. Alexandria agreed. It was an abject surrender. The leadership of the country in Washington watched, helpless, as Gordon exacted the humiliating ransom with impunity and then proceeded back down the Potomac on September 2 with his booty.

Secretary Jones tried to obstruct Gordon’s descent. He had already ordered John Rodgers, Oliver Hazard Perry, and David Porter to help with Washington’s defense, but they arrived too late. Jones now hoped that the trio could perform some miracle and stop Gordon as he struggled back to Chesapeake Bay. On August 28 Jones wrote to Rodgers, asking if he would “annoy or destroy the enemy on his return down the river.” The next day, after Jones found out about Gordon’s demands on Alexandria, he angrily ordered Rodgers to bring six hundred fifty men to Bladensburg and await further orders. Rodgers immediately dispatched Porter with a hundred men to march to Washington and then came along himself with additional men, but not the six hundred fifty Jones wanted.

Upon being informed of what Rodgers was doing, Jones wrote Porter on August 31, ordering him to take his detachment of seamen and marines, which had just arrived, and establish batteries with six eighteen-pounders “to effect the destruction of the enemy squadron on its passage down the Potomac.”

On September 2 Acting Secretary of War Monroe, in desperation, suggested to Rodgers that he might reestablish the post at Fort Washington that night. At the time, Rodgers was busy organizing fire ships to attack Gordon as he came down the river, and he ignored Monroe.

The next day, September 3, Gordon’s flagship Seahorse, the 50-gun Euryalus, and the bomb vessel Devastation were two and a half miles below Alexandria when Rodgers attacked them with three small fire vessels, conned by lieutenants Henry Newcomb and Dulany Forrest and Sailing Master James Ramage. Rodgers was in the river, directing them from his gig. The wind did not cooperate, however, and they failed to reach their targets. Gordon’s boats towed the flaming fire ships away. At the same time, Gordon’s men went after Rodgers, firing at him for thirty minutes as he raced away in his gig.

Rodgers tried again the next day, planning to send Lieutenant Newcomb back with a flaming cutter, but the wind again would not cooperate, and when a frigate came after Newcomb, he had to scurry away. That night, Gordon sent some barges to attack Rodgers’s boats, but Rodgers beat them off. At seven o’clock the next morning, Rodgers assembled another fire ship. He hoped to coordinate with Porter, who had established himself farther downriver at the White House, a navigational landmark below Mount Vernon, thirty miles from Washington. But that did not work out either. Rodgers was forced to give up.

As Gordon continued down the Potomac, he encountered Porter with two hundred Virginia militiamen, under Brigadier General John P. Hungerford, at the White House (Belvoir plantation) on September 4. Master Commandant Creighton accompanied Porter. They had only three long eighteen-pounders, two twelve-pounders, and two four-pounders to begin with, but more came, and they put up a gallant fight. For the entire day on September 5, Gordon bombarded Porter’s batteries, but with little effect. When Porter continued to fire back, Gordon committed more ships to the assault. As the hours passed, more cannon arrived for Porter. Army Captain Ambrose Spencer of the U. S. Artillery, who had been second in command at Fort Washington when it was blown up, fought alongside Porter with a small contingent. On the morning of September 6, Gordon brought up more of his big ships and commenced a terrific bombardment, which finally forced Porter and the Virginia militiamen to retire. Captain Spencer and his men convinced Porter by their bravery and sacrifice “that it was not want of courage on their part which caused the destruction of the fort.”

Oliver Hazard Perry was the last obstacle Gordon had to face. Perry had hastily thrown up a battery at Indian Head, Maryland, with a single eighteen-pounder in it that arrived thirty minutes before Gordon appeared. Perry had little ammunition and started firing right away. Militiamen working with him had six-pounders, and they kept up a spirited fire. All the ammunition was quickly expended, however, and Perry and the militiamen were forced to retire under heavy fire from Gordon’s ships. The exchange went on for an hour. Perry had one man wounded during the fight.

Before Gordon extricated himself from the Potomac completely, Admiral Cochrane received word that Gordon might be in trouble and began moving his big fleet toward the river on September 7. The next day the fleet was in the Potomac, making its way slowly upstream. Cochrane and his big ships were twenty miles from the mouth of the river on September 9, when Gordon suddenly appeared triumphantly with twenty-one prizes and the bomb ships and rocket vessel that were indispensable for an attack on Baltimore, or another place like Rhode Island, which Cochrane was considering.

In the end, Rodgers, Porter, and Perry put up as spirited a fight as they could with almost no resources, and they made an important contribution to the war by delaying Gordon and Cochrane, which gave other cities that were under the gun, like Baltimore, additional time to prepare their defenses.

Even Boston was finally realizing that the threat of a British invasion was real. Alexandria was known as a Federalist city with pro-English sympathies, but that had not saved it from a thorough looting by Gordon.

WHILE GORDON WAS on his diversionary raid up the Potomac, Captain Sir Peter Parker had been busy with his diversion as well. He wrote to Admiral Cochrane that he had “been continually employed in reconnoitering the harbors and coves and sounding the Bay and acting for the annoyance of the enemy.” He found Annapolis practically defenseless and thought it could be taken easily. He also reconnoitered near Baltimore.

On August 30, after he had written to Cochrane, Parker became engaged in a sharp fight with Maryland militiamen near Chestertown, Maryland. He led a charge against what he thought were 500 militiamen, but were in fact fewer than 100. Whatever their number, he was confident they would run, as militiamen had several times before when he challenged them. This time, however, they stood their ground. Parker had 104 men armed with bayonets, pikes, and pistols. He attacked the militiamen at Caulk’s Field near Chestertown around eleven o’clock during a dark night. Early in the action, Parker was shot and killed. His men fought on, uncertain how big a force they were fighting. Eventually, the Maryland militiamen ran out of ammunition and pulled back, but the British, believing they were up against a much larger force, did as well, retreating to their ship, the Menelaus. During the fracas, no Americans were killed; 3 were wounded. The British had 14 killed and 27 wounded.

AFTER THE WASHINGTON and Alexandria disasters, some Federalists felt vindicated. They had predicted blows of this kind, and they were not reluctant to say, “We told you so.” “The Federalists now have great consolation that they always with all their might opposed this war,” the Salem Gazette wrote. “They supplicated and entreated that it might not be declared, for they foresaw and foretold the ruin and misery and disgrace it would inevitably bring upon the nation.”

Most of the country, however, was appalled and angry at the wanton destruction of the capital, as were Europeans. The French were loud in their condemnation of the desecration of Washington. Even some British newspapers were disgusted by what had happened.

WASHINGTON WASN’T THE only place Cochrane’s squadrons were attacking. On April 7–8, 1814, the British sent a raiding party up the Connecticut River to Essex (then known as Pettipaug Point) and destroyed twenty-seven vessels without suffering any losses.

On May 22, Commodore Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy sailed his flagship Ramillies from its station off the eastern end of Long Island to Narragansett Bay near Boston. Seven days later, he transferred to the frigate Nymph and sailed up the coast to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to ascertain if an attack on the battleship Washington, under construction there, was feasible. Hardy did not want to use the 74-gun Ramillies to reconnoiter for fear it would alarm the countryside and warn Isaac Hull.

On June 16, Hardy reported back to Cochrane that after a thorough reconnaissance, he believed the Washington could be easily destroyed. Hull had done everything he could to prepare a defense with extremely limited resources. He was getting little support from either the state government or the national government. Armstrong did not think Portsmouth needed help. Cochrane decided to postpone the project, however, even though he knew that destroying the battleship would be popular in England. The Times of London would certainly have loudly applauded.

Cochrane had a more important assignment for Hardy—seizing Moose Island in Passamaquoddy Bay. The important harbor of East port was on the island, and Cochrane had orders from Bathurst to occupy it. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pilkington sailed from Halifax in the sloop Martin, and on July 7 he met Hardy in the Ramillies. Hardy was coming from Bermuda accompanied by two troop transports, which carried six hundred men, and the bomb vessel Terror. Pilkington landed at Eastport, in the Maine District of Massachusetts, and took over Moose Island. The eighty-six American defenders at Fort Sullivan, led by Major Perley Putnam, reluctantly surrendered on July 11 without a fight. Putnam had no other choice.

Raids were continuing in Boston Harbor. When the 38-gun Nymph, under Captain Famery P. Epworth, returned from her scouting trip to Portsmouth and was back at her station off Boston, she immediately went on the attack. “On the night of 20–21 June the Nymphe’s sailing master and a small party rowed from the frigate into Boston Harbor to burn a sloop ‘within a mile’ of the Constitution,” Commodore Bainbridge reported. He was commandant of the Boston Navy Yard and had to worry about not only the Constitution but also the 74-gun Independence , which was under construction. The Admiralty wanted both destroyed. Bainbridge also had responsibility for protecting Boston Harbor and the city. He got no help from the ultrafederalists in Boston, but most ordinary people supported him. In another daring raid on July 7, armed barges from the Nymphe managed to cut out five more small sloops.

British raids in the summer and fall of 1814 in New England were extensive. They struck in the district of Maine and in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. Both Wareham and Situate in Massachusetts were attacked. No place was safe. The Bulwark raided Saco, Maine, on June 16. Bath and Wiscasset in Maine were attacked the day before, and Rye, New Hampshire, was threatened.

A particularly vicious raid was conducted against Stonington, Connecticut. Rear Admiral Henry Hotham, commander of the blockading squadron off Long Island, was obliged to carry out Cochrane’s order to lay waste to towns, and he set his sights on Stonington. Hotham ordered Captain Hardy, who had just returned from Maine, to do the job. Hardy found the whole business distasteful: he thought that attacking defenseless towns was both cowardly and stupid. Nonetheless, he carried out his instructions and bombarded Stonington—an innocent place that had no strategic value—beginning on the evening of August 9. Hardy employed the 38-gun frigate Pactolus, the 20-gun brig Dispatch, the bomb vessel Terror, and barges from the Ramillies. The shelling went on for about four hours, ending at midnight. The townspeople bravely defended Stonington with three cannon. They were helped immeasurably when 3,000 Connecticut militiamen arrived to defend the fort that had been firing fruitlessly at the warships.

The bombardment resumed the next day for several hours. The British ships were joined by the Ramillies and the 18-gun Nimrod. Later, Hardy suspended the attack and did not resume until the afternoon of August 11, when the Terror threw shells into the town sporadically until evening. The following day, the Terror resumed her desultory shelling until noon, when Hardy called off the attack and left, greatly embarrassed.

Of far greater importance, the British initiated a large-scale invasion of eastern Maine. On August 26 Lieutenant General Sir John. C. Sherbrooke, the governor of Nova Scotia, and Rear Admiral Edward Griffith left Halifax with twenty-four ships and 2,500 men for the assault. Griffith’s squadron included the 74-gun Dragon, under Captain Robert Barrie; the 74-gun Bulwark; the frigates Endymion, Bacchante, and Tenedos; the sloop Sylph; and two brigs, Rifleman and Peruvian. Sherbrooke’s men landed unopposed at Castine in Penobscot Bay on September 1. Twelve thousand men suitable for military service were in the northeastern part of Maine, but Madison’s war was not popular there, and the militias were poorly organized. Sherbrooke met no opposition. The tiny American garrison of regulars at Castine destroyed their small fort and withdrew up the Penobscot River. Sherbrooke then sent amphibious forces against Belfast, Hamden, Bangor, and Machias. Soon all of eastern Maine, from the Penobscot River to Passamaquoddy Bay, was in British hands. Federalists in Boston liked to think that the people of eastern Maine welcomed the British, but the general sentiment was more one of neutrality and a wish that the war would be over. Sherbrooke soon annexed the captured territory, and the Times was positively gleeful. “The district we speak of is the most valuable in the United States for fishing establishments,” the editors wrote, “and has a coast of 60 leagues abounding in excellent harbors, from whence much lumber is sent to Europe and the West Indies.”

By the end of August 1814 Admiral Cochrane’s raids had been eminently successful. He had captured and burned the American capital and embarrassed Madison, and he had acquired a large chunk of Maine with no opposition. Smaller raids along the coast had also gone well. More importantly, his attacks did not unite Federalists and Republicans, as might have been expected; the country remained divided. The political parties were as bitterly opposed to one another as they had always been, perhaps even more so. Madison was desperately trying to hold the country together and continue the war. But his chances of withstanding the British invasions that were coming from the north and the south appeared extremely poor. Admiral Cochrane, on the other hand, as he prepared to tackle Baltimore and then New Orleans, was flush with victory, his confidence at a high level.