Brammer’s parents’ house was part of a formerly middle-class, now workingman’s, enclave called Oak Cliff in Dallas, next to a vacant lot and a winding little creek long dry. His father kept an extra fridge stocked with soda pop on a screened-in back porch—he was a plain fool for Hydrox and Dr Peppers. (Kate Brammer; all images provided by Sidney and Shelby Brammer unless noted otherwise.)

Brammer always referred to himself as a “menopause baby.” As the child of older parents, he was doted on and left alone in almost equal measure. Hence, his frequent boredom. (Kate Brammer)

Brammer’s mother Kate never spoke of her brief first marriage to a man she never named. He was the father of Brammer’s older half-sister, Rosa. As a rather isolated child, Brammer used to love to go to the movies with his mother, often in the Texas Theatre with its ceiling of fake stars. (Rosa Gunnell)

Brammer grasped early that his father, a lineman for the Texas Power and Light Company, was a major agent of change, waving his wrenches and harnessing the power that brought the world, shouting, into the boy’s room through the Crosley radio.

“Charming, reckless, crazy Billy,” Brammer’s friend, Grover Lewis, called him. At North Texas State Teachers College, in the early 1950s, Brammer developed a “growing hipness about things in general,” said his daughter Sidney.

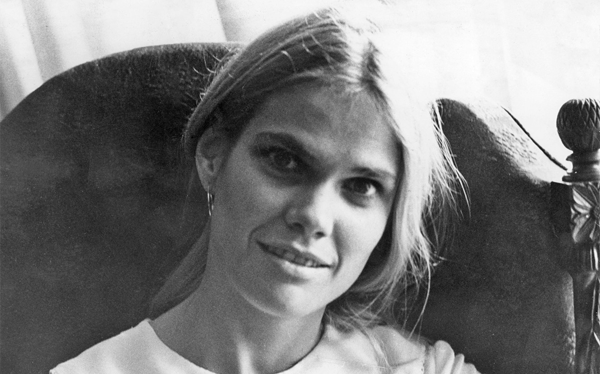

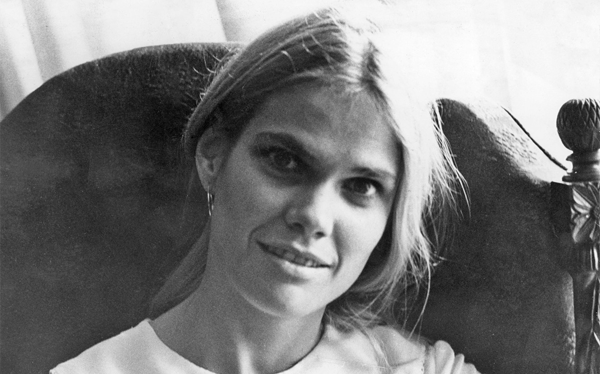

Brammer’s friend, Robert Benton, who later had a successful movie career, took this “art” photo of Nadine one night in the early 1950s when Brammer was out of town. Later, Brammer was not happy when he learned of the photo session. (Robert Benton)

Sidney was born in August 1952, in Austin. She was an unusually pretty infant, said Benton, fair, delicate, and Brammer was besotted. (Nadine Brammer)

When Sidney was a baby, Nadine shuttled back and forth between Austin and her mother’s house in McAllen. She was unhappy staying home while Brammer worked during the day and went out with friends in the evenings. Brammer tried to make a home for the family in Austin, fixing up a study that Sidney frequently commandeered as a playroom. (Nadine Brammer)

Shelby, born in the summer of 1954, was as gorgeous as her big sister and just as beloved by her father. “I have no memories of Nadine and Billy Lee being together,” Shelby said. “He’s in DC and she’s fed up.” (Nadine Brammer)

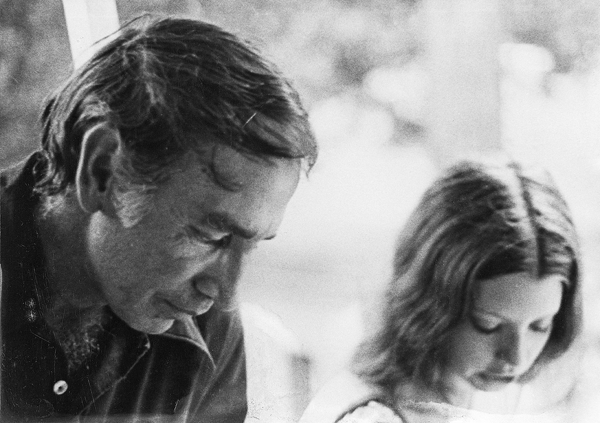

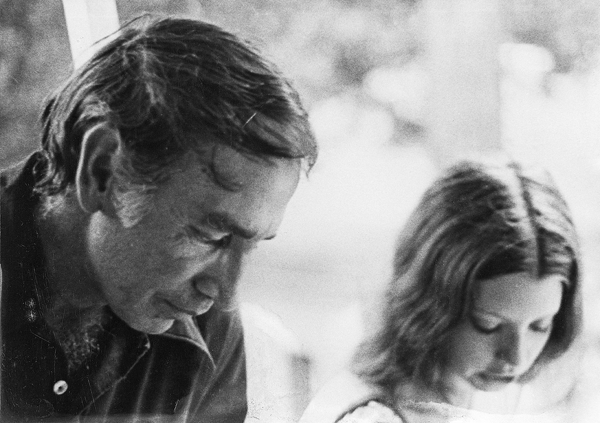

Lyndon Johnson hailed his policy of hiring couples as a progressive experiment in fostering “team spirit,” but Nadine (lower right, with Brammer) admitted that this portrait of unity on the Capitol steps was an election year put-up job: “I was already straying sexually and emotionally.” (Courtesy of the publisher)

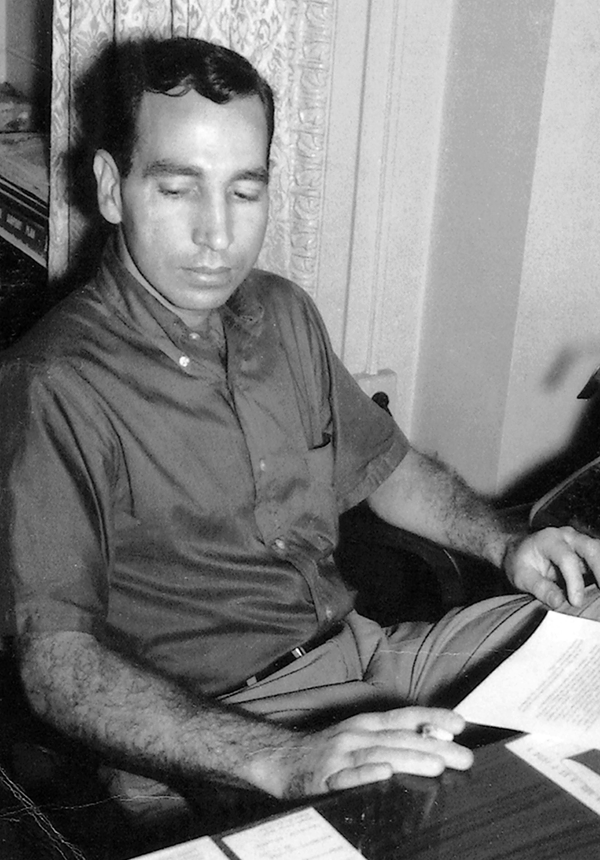

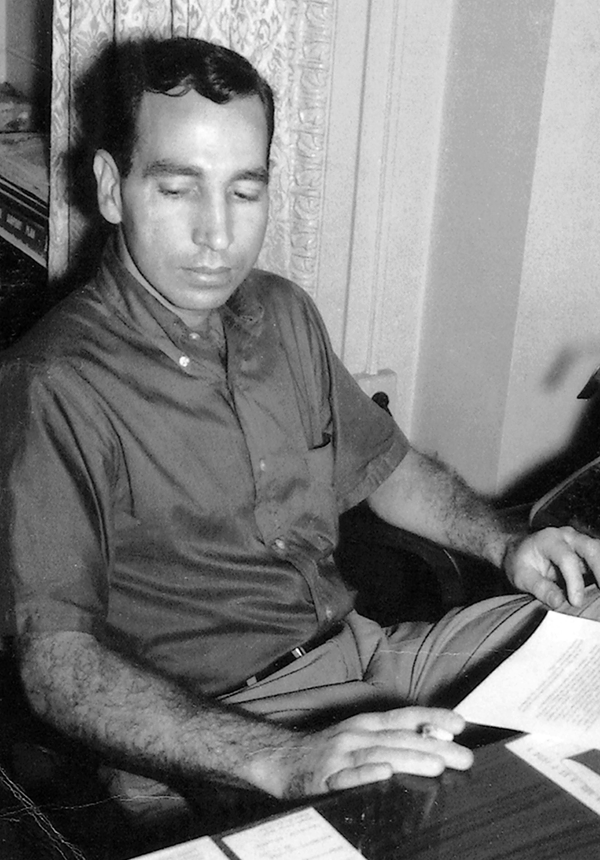

Located directly underneath Richard Nixon’s office, Brammer shared Room 201 with another Senate staffer and entertained colleagues by inviting them to come hear the “groan of vice-presidential plumbing.” Here, Brammer wrote most of The Gay Place late at night, high on speed and swaying to the sound of Paul Desmond records.

“If you’ll name that boy after me, I’ll give him a heifer calf and he’ll have a whole herd by the time he’s twenty-one,” LBJ told Nadine when she informed him she was pregnant and would soon leave his staff in Washington to return to Austin. At an early age, Willie became skilled at complicated magic tricks, which delighted Brammer. (Billy Lee Brammer)

Brammer campaigned for the Kennedy-Johnson ticket, delaying proofreading the galleys for The Gay Place. In Dallas, along with LBJ and Lady Bird, he got caught in the middle of an angry group of wealthy women who shouted curses at Johnson for “selling out” to Eastern liberals and communists. The press dubbed the group the Mink Coat Mob. (Austin-American Statesman)

Brammer’s trip to Texas in 1961 for book-signing events caused him no small anxiety. He feared his old liberal pals might resent his politics in the novel, and he was not returning to a wife but to an antagonist in a divorce case. To top it all, his mother objected to the way his name appeared on the book cover, as “William Brammer.” “Darn it, we named you Billie Lee!” she said. (Austin-American Statesman)

In January 1960, Brammer moved into a small apartment at 65 Bedford Street in New York and frequently went to movies with Robert Benton at the Museum of Modern Art. “The Village is pleasant and not exactly the wicked and reckless place it is advertised to be,” he wrote Nadine. (Ina Backman)

Dorothy was a sorority dropout and an English major at the University of Texas when she met Brammer. After a mutual friend introduced them, she thought, “Ah, be still my heart. O English major heart.” “Everyone in town knew who he was. I think I took the rollers out of my hair.” Brammer wrote a paper for her, which earned a C+ for “poor sentence structure.”

“Darthy, my love, I’m off to Washington,” Brammer said. Dorothy asked, “What are you going to do with me?” He answered, “Well, I’ll just marry you and take you with me.” “I thought, ‘Sounds like fun,’” Dorothy said.

The wedding was held in Dorothy’s father’s house in Houston and British-born classics professor John Sullivan served as best man. Sullivan’s date was Barbara Jordan, who in 1966 would become the first African American woman elected to the Texas Senate. A friend later said, “I can just imagine Dorothy’s father’s reaction when he came to the realization he was throwing what was doubtless the first integrated wedding on his block.”

In 1965, Brammer and Dorothy moved into the Daniel H. Caswell House at 15th and West Avenue in Austin, a turn-of-the-century Victorian / Colonial Revival home that was falling apart. It rented for $250 a month and became an epicenter of “wild abandon.” (Bob Simmons)

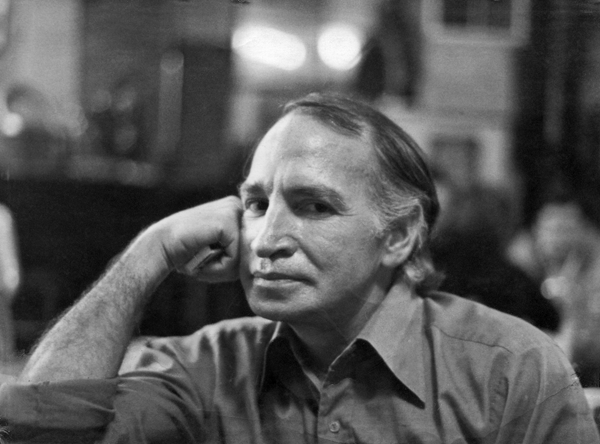

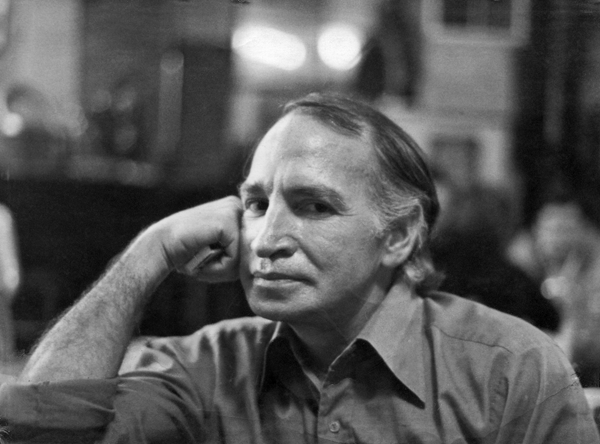

Brammer grew a rakish mustache and bought new clothes when he took a job teaching journalism at SMU in Dallas. The city presented a “glum landscape,” he mourned: “While not the unremitting drag I half expected, [it] is vaguely dissatisfying all the same. I had thought our friends in Austin, SF, NYC, etc. were troubled, sad, frequently depressing or boring. Much worse here.” (Gary Cartwright archive and estate)

Brammer was a lifelong teacher, a companion, a grown–up kid, according to Shelby. “Whenever he was with you, his attention was focused solely on you,” she said.

Robert Benton marveled that Brammer never made an enemy in his life. He took great care to maintain his friendships. His pal Tary Owens said he “was the only person about whom you could say, ‘He stole my wife and I’m not mad at him.’” (Bob Simmons)

A literary celebrity, Brammer might vow to stay away from parties, but the parties came to him. One midnight, Jay Milner “found Billie Lee sitting alone in a corner” of his house drinking a Dr Pepper while a party caroused around him. “Am I this much fun?” Brammer asked his friend. (Bob Simmons)

Bud Shrake was covering sports for the Dallas Morning News when Brammer moved into Shrake’s apartment in the early 1960s. It was through Shrake that Brammer met Jack Ruby (Shrake was dating Jada, Ruby’s premier stripper at the time), and after the assassinations and LBJ’s ascendency to the presidency, Brammer thought his life would turn around. No one had better LBJ stories than he did. (Austin-American Statesman)

“[Bill] got a lot of ego-satisfaction from being the center of attention with those guys,” Sidney said of the time her father spent with this group of younger writers and their companions (Shrake, Kathy Lowry Deely, and Larry L. King, standing; Doatsy Shrake, Holly Gent Palmo, Pete Gent, and Brammer, seated). “They were big and drunk and loud. He’d sit quietly and then let out a pithy remark and they’d fall all over.”

“I saw that he’d gotten old,” Sidney said. It became “almost painful to visit him in his rattrap apartments” but “one often had a need to see him—because Billie Lee had a way of getting to the quick of your deepest despond, making you laugh at it.” (Wayne Oakes)