Do you like to “tell it like it is” and appreciate when others “lay their cards on the table”? Do you feel it is better to “shoot from the hip” than to “beat around the bush”? Most Americans probably subscribe to the maxim, “Honesty is the best policy.” After all, isn’t our first president, George Washington, revered for his truthful confession in the cherry tree incident? Before we pat ourselves on the back for our forthrightness and square dealing, however, it is essential to get a larger perspective. We may not be quite as candid as we presume we are.

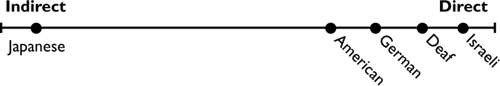

If ordinary Americans regard themselves as frank and aboveboard, it may come as no surprise that the majority of literature in the field of intercultural communication supports this assertion. “America shows a preference for direct, accurate, clear, and explicit communication”(Zaharna 1995). “Americans’ tendency to use explicit words is the most noteworthy characteristic of their communication style”(Okabe 1983). “Americans are characterized as always forthright, direct, and clear” (Miller 1994). (These three citations are quoted in Nelson et al. 2002, 41.) In fact, countless scholars have made the classic comparison of Japanese culture’s indirect communication style with American culture’s direct style. If graphed on a continuum, it would look like this:

In Japan, saving face and preserving group harmony are of paramount importance. This social consciousness often leads to foreigners’ frustration with what they term an “ambiguous” Japanese communication style. In an essay entitled “Sixteen Ways to Avoid Saying ‘No’ in Japan”, author Keiko Ueda explains, “One must always think of the other’s feelings and speak to avoid hurting those feelings” (1974, 186). It is true that compared with Japanese indirectness, American communication style is decidedly more direct.

Let us assume for a moment, however, that another culture (we can call it “X”) practices a style of communication that is considerably more direct than the American variety. Suppose a member of Culture X delivers a critical remark to an American in a blunt manner. Since Americans already pride themselves on being straight shooters, any comments that appear to be even more direct than their own may well be judged as “just plain rude.” The following graph depicts the way it might feel to many Americans.

Recent literature has, in fact, shown that there are quite a few cultures that practice a much more direct style of communication than American culture does and that regard with annoyance the American tendency to “beat around the bush.” In Germany, where the direct approach is valued, “speaking plainly when it’s for another person’s own good will not only not be taken as a criticism…but will be seen as a sign of consideration.” And “a true friend or colleague doesn’t protect one from the truth but helps one see it” (Storti 2001, 241–42). Similarly, in Israeli culture, directness demonstrates “intimacy and solidarity” and “is associated with the expression of respect rather than disrespect” (Katriel 1986, 38, 116). In Korean collectivistic cultures, “a frank expression of criticism is done out of a ‘we’ feeling and in most cases is appreciated as a sign of ones’ utmost love and concern for the target individual” (Kim 1993, 16). And in American Deaf culture, “straight talk” is the name given to the direct style of communication, which is valued for its lack of ambiguity. Among Deaf people, “hinting and vague talk in an effort to be polite are inappropriate and even offensive” (Lane 1992, 16).

Given the previous discussion, a more accurate representation of the indirect/direct continuum might look like this:

A key distinction in American culture regarding the choice of a direct or indirect approach may be the subject that is under discussion. South Korean Jin K. Kim makes this observation: “Americans are almost brutally honest and frank about issues that belong to public domains,” but when it comes to delivering criticism,

Their otherwise acute sense of honesty becomes significantly muted when they face the unpleasant task of being negative toward their personal friends. The fear of an emotion-draining confrontation and the virtue of being polite force them to put on a facade or mask. Instead of telling a hurtful truth directly, Americans use various indirect communication channels to which their friend is likely to be tuned. (1993, 15)

In my experience, the differences between direct and indirect communication styles in American Deaf and hearing cultures represent the most problematic area with the largest potential for misjudgments, misunderstandings, and hurt feelings on both sides. Although these misconceptions may be the source of much confusion between Deaf and hearing consumers of interpreting services, interpreters themselves and other hearing people involved with the Deaf community are not immune from their impact.

Here is a short quiz for you to begin to examine your feelings regarding direct and indirect styles of communication. In Section VII you will find the exercise “Translating between Direct and Indirect Styles,” which will give you some further practice in one of the most challenging aspects of our work as interpreters.

Directions: Respond with a word or two to describe your first reaction to these questions (e.g., frustrated, hurt, confused):

In completing the previous sentences you may have noticed that some of the situations provoked rather strong reactions because of your assumptions about direct and indirect communication styles. Use these reactions as a potential “red flag” for future intercultural encounters. If you find yourself internally fuming with thoughts such as “What is your point?” “What a rude question!” or “Well, you asked me my opinion,” ask yourself if it is possible that you are reacting to a difference in communication style.