2 Canada’s Shifting Borders

An Overview of Market and

Human Movements

Geoffrey Hale

Patterns of cross-border trade, travel, and migration within and beyond North America have evolved substantially since the 1990s, with significant implications for Canada’s border-management policies and cooperation with the United States and other major countries. Canadian border management is characterized by extensive cross-border and wider international cooperation. Administrative cooperation with US border and security agencies, and through international organizations, has increased substantially—notwithstanding broader systemic challenges which threaten to disrupt the international trading system, and which, more recently, have disrupted international travel. Indeed, ongoing cooperation is critical to the effective management of rising levels of informal migration. This chapter summarizes major trends in cross-border travel and trade since the turn of the twenty-first century. It reviews major developments or uncertainties currently challenging or threatening to disrupt Canadian and North American borders and bordering regimes in three major areas: trade, human movements, and infrastructure. Finally, it assesses major options and priorities in addressing these challenges.

Changing Patterns of Trade and Travel

National regulation of cross-border movements ebbs and flows as a reflection of the relative security—and insecurity—of domestic populations, with the latter particularly acute following major shocks. The rapid expansion of cross-border traffic which followed negotiation of Canada-US and subsequent North American free-trade agreements (CUSFTA and NAFTA, respectively) went into reverse after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001. Similar developments are anticipated in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic, which largely shut down international travel and disrupted supply chains. Post-9/11 shocks were followed by an extended period of adaptation, characterized initially by a mix of unilateral and cooperative security measures, and subsequently by cooperative efforts to integrate border security and facilitation among leading industrial nations. The 2008–2009 international economic crisis and its aftermath encouraged efforts at greater cooperation for a time. However, the pandemic-related threats and disruptions of 2020 triggered a wide mix of discrete national responses as many governments scrambled to repatriate their nationals travelling or living abroad while restricting wider international travel, with exceptions for “essential” sectors and workers.

Within North America, the bilateral Smart Border Accord (SBA) negotiated after 9/11 established an initial framework for Canada-US cooperation on border security and selective trade facilitation. SBA reflected a broader American strategy to “push out” borders through a mix of enhanced offshore screening of containers, cargo, and travellers, and trusted-trader and -traveller programs in different transport modes (Flynn 2003; Hale and Marcotte 2010). In 2002–2004, the two countries also signed and ratified the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA), intended to manage and contain flows of migrants transiting through one country to seek asylum in the other.

Successive Canadian governments and US administrations sought to institutionalize processes for cooperation and selective coordination on border and related regulatory issues after 2009, including the Beyond the Border (BTB) process initiated in 2011, albeit with modest success (Auditor General of Canada 2016). These processes have continued despite growing trade tensions within and beyond North America, along with sharp spikes in irregular migration to Canada since 2017, a sub-regional dimension of a much larger, international challenge. However, the eight-year process for implementing reciprocal entry-exit information-sharing processes on land borders (negotiated in principle in 2011) and the glacial pace of discussions about pre-clearance of cross-border cargo shipments demonstrate the continuing challenges of reconciling differences in national border-management systems and priorities.

Post-9/11 security measures contributed to varying degrees of border thickening after 2001, offset or reinforced by the effects of ongoing exchange-rate shifts for Canadian and American travellers, respectively (Smith et al. 2018). Overall traveller volumes dropped 16.3 percent over 2000–2005, particularly on land borders, as noted in tables 2.1 and 2.2, with cyclical, but regionally varied recoveries after 2009. Canadians adapted more rapidly to the introduction of US passport requirements for all cross-border travel, as rising Canadian dollar exchange rates encouraged more cross-border travel and shopping. However, passport-ownership levels still vary widely across regions in both countries.

Table 2.1. Persons Entering Canada by Mode of Transport

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 | |

Total Int’l Travellers* |

95,819,500 |

80,239,681 |

82,431,780 |

82,842,007 |

88,587,177 |

Auto + |

75.1% |

69.7% |

66.9% |

61.0% |

57.0% |

Air |

18.9% |

24.3% |

28.4% |

34.4% |

38.2% |

Bus |

3.4% |

3.0% |

1.5% |

1.6% |

1.9% |

Sea |

1.1% |

1.6% |

2.1% |

2.0% |

1.8% |

Other |

1.3% |

1.3% |

0.9% |

0.8% |

0.9% |

Train |

0.2% |

0.2% |

0.2% |

0.2% |

0.2% |

*Net of aircrews, new residents Sources:

Data from Statistics Canada (2020a); author’s calculations.

Table 2.2. Volumes of Travellers Entering Canada by Major Mode of Transport (Year 2000 = 100)

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 | |

| Auto | |||||

Canadians |

100.0 |

88.0 |

109.5 |

99.8 |

92.4 |

Americans |

100.0 |

67.8 |

42.4 |

42.1 |

46.4 |

Other foreign* |

100.0 |

71.7 |

78.3 |

97.8 |

176.7 |

| Air | |||||

Canadians |

100.0 |

94.8 |

127.3 |

146.0 |

183.3 |

Canadians |

100.0 |

138.0 |

193.1 |

256.3 |

273.7 |

Americans |

100.0 |

98.0 |

84.0 |

104.9 |

129.1 |

Other Foreign |

100.0 |

100.8 |

97.3 |

120.1 |

154.4 |

*All land travel modes. Sources:

Data from Statistics Canada (2020); author’s calculations.

Continuing trends in increased air travel noted in table 2.2 were independent of land-border traffic, particularly for Americans. Canadians diversified their travel destinations, while trends in cross-border travel varied widely across regions: declining sharply in Atlantic Canada, but increasing across much of western Canada, subject to ongoing exchange-rate fluctuations (Hale, forthcoming). These trends were disrupted by the 2020 pandemic, which resulted in extensive governmental restrictions on non-essential travel, severely disrupting the airline sector.

Canada experienced notable shifts in trade patterns with significant border implications in the decade following the 9/11 attacks. A steady, if incremental diversification of Canadian trade after 2002 is noted in table 2.3, before Chinese sanctions imposed in 2019 resulting from growing geopolitical tensions. Wide variations remain across sectors and commodities as indicated in figure 2.1. Key factors included changing terms of trade for major export sectors (including structural and cyclical shifts in commodity prices), rising trade with Asia and, more recently, the expansion of offshore e-commerce imports. Important border-related barriers to trade diversification include variations in rules of origin across countries and trade agreements (discussed in chapter 3), and differences in food- and other product-safety standards requiring separate processing or transportation arrangements for particular commodities by target market. Such measures were subject to growing politicization, as seen in the 2019 spike in Chinese customs declarations and other administrative barriers to Canadian canola and pork exports, and in the complex interaction of domestic producers’ and importers’ interests surrounding US and retaliatory Canadian metal tariffs and subsequent rules of origin aimed at limiting trans-shipment of imports from outside North America (Powell 2018; Reuters 2018; Vanderklippe 2019; Lardner and Fenn 2019).

Table 2.3. Diversification of Canadian Trade

|

2002 |

2010 |

2018 |

Exports as % of GDP |

31.1 |

29.8 |

31.8 |

Trade as % of GDP |

58.8 |

60.8 |

65.8 |

% of Exports to us |

80.7 |

70.0 |

70.7 |

Goods |

83.9 |

73.1 |

73.9 |

Services |

60.2 |

54.4 |

55.2 |

% of Imports from us |

69.8 |

61.7 |

62.3 |

Goods |

71.5 |

62.8 |

64.4 |

Services |

60.9 |

57.2 |

53.8 |

Source: Statistics Canada (2019).

Despite efforts to tailor trusted-trader programs to the needs of the heavily integrated automotive (and related) sectors, rising energy prices and exchange rates contributed to sharp shifts in cross-border traffic away from manufactured goods largely carried by truck toward bulk commodity traffic largely shipped by rail and pipeline over 2005–2014. More recently, increased use of electronic data systems, including the Automated Commercial Environment (ACE; US) and Advanced Commercial Information (ACI; Canada), increased predictability of customs arrangements for cross-border truck shipments for larger firms and products not subject to complex rules of origin, and other technical “enforcement” measures. However, further research is necessary to identify means of addressing regional and sectoral differences that would permit progress toward closer harmonization and wider utilization of Canadian and US trusted-trader programs, with potential for ultimate extension to Mexico, subject to the wider political environment arising from current US and Mexican electoral cycles.

Figure 2.1. Share of Merchandise Exports to Emerging Markets (%).

Source: Reproduced with permission of Export Development Corporation.

Trade Patterns and Border Infrastructure

Rising trade with China and other Asian countries and the rapid growth of containerization prompted the rapid growth of inbound and outbound traffic through West Coast ports since the late 1990s (American Association of Port Authorities 2020), facilitated by substantial and continuing investments through the federal gateways and corridors strategy (and its successors) after 2006. By 2017, cross-border North American traffic and extra-continental trade accounted for two thirds of revenues for Canada’s two major railways (Hale, forthcoming). These developments lent themselves to extensive federal/provincial/private-sector cooperation on behind-the-border infrastructure in Canada to anticipate and resolve bottlenecks. However, supply-chain disruptions arising from the 2020 pandemic, sometimes reinforced by competitive state-procurement practices, have led some observers to suggest that existing just-in-time supply-chain networks may give way to just-in-case shifts in production and distribution capacities in some sectors (Lynch and Deegan 2020).

By contrast, coordination of border infrastructure with the United States has been sporadic, with selective exceptions, despite expanded efforts at information sharing and pilot projects aimed at enabling pre-clearance of cross-border freight under the post-2011 BTB process. Implementation of the 2015 Canada–US Preclearance Agreement, which extends certain air provisions to other modes of transportation, remains a work in progress. Its implementation for cargo shipments remains a relatively distant prospect, although the Pre-Arrival Readiness Evaluation (PARE) pilot project at the Niagara region’s Peace Bridge (Rienas 2019) offers the potential to expedite cargo traffic through US ports of entry for Canadian ports with enough physical capacity to adopt similar measures. These constraints reflect the different accountability structures, administrative priorities, and budgetary processes of border agencies in each country, along with vagaries of bureaucratic and local politics. Other significant factors include legal differences governing law-enforcement procedures and negotiations around the privileges and immunities of law-enforcement personnel, including those of border agencies, physically located in the other country (Stana 2008). These factors, combined with the challenges of obtaining efficient police support in case of emergencies, have slowed processes aimed at establishing joint ports of entry in the twenty-five (of 121) ports of entry reporting crossings of fewer than fifty cars daily in 2018, although such initiatives remain under active review (Goodale 2019).

Managing border infrastructure is particularly challenging in major urban centres such as Detroit–Windsor or Buffalo–Fort Erie, given the need to coordinate regulatory requirements from multiple levels/orders of government, with attendant risks of politicization and protracted litigation (Savage 2015; Eagles 2018). Shared provincial/state interests and complementary processes for managing the maintenance and periodic improvement of border infrastructure remain critical to effective cooperation. For domestic borders and related corridor infrastructure, stable, long-term federal funding and continuing federal/provincial (and municipal) cooperation remain critical to leveraging private-sector infrastructure in rail and pipeline facilities. Domestic failures in coordination, including those involving Indigenous communities, remain critical factors contributing to trade bottlenecks in Canada’s major gateways and corridors.

Discussions of opening Canada’s major airports to private and other institutional investment to expand capacity have run aground over the competing strategic objectives of governments, airport authorities, and airlines, combined with public skepticism over the resulting distribution of costs and benefits (Curry 2018; Angus Reid Institute 2017). These debates point to the very different roles that these transport and economic development hubs play within their respective communities and regions, and the risks of “one-size-fits-all” initiatives in this sector. However, BTB-related administrative improvements have enabled pre-screening of passenger baggage to the United States on connecting flights from eight Canadian airports.

The environment for Canada’s diverse cross-border energy trade has also experienced major changes since the mid-2000s. Technological changes, particularly hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling, had transformed the economics of oil and gas exploration and production (Canada’s largest export sector in most years since 2005), along with North American and wider international energy markets, even before their further disruption by the global oil-price war of 2020 (noted in chapter 5). Improvements in high-voltage direct-current transmission technologies have increased the feasibility of long-distance transmission corridors, but also resulting conflicts over land-use management in both countries. Growing political controversies over the expansion of cross-border and, subsequently, domestic pipeline capacity after 2009 led to systematic litigation in both countries, which have reinforced internal bordering processes supervised by state and provincial regulators, First Nations, and Native American tribal governments (Harden-Donahue 2017; Hale 2019a). These bottlenecks prompted cyclical increases in oil-by-rail shipments to compensate for shortages of pipeline capacity, increasing potential bottlenecks for other export commodities. In 2018, the Alberta government mandated production cutbacks to offset price discounting from pipeline bottlenecks. Disputes with and among factions within the Wet’suwet’en people over rights-of-way for the Coastal GasLink pipeline in British Columbia led to effective blockades of major rail lines across Canada for several weeks in 2020 (Wilson-Raybould 2020; Saltsman 2020). Other political controversies have affected the expansion of electricity-transmission corridors from Quebec and Atlantic Canada to the New England states (Tomblin, forthcoming).

The rapid growth in international e-commerce creates other border-management issues. A 2018 federal report estimates 18.5 million e-commerce users in 2017, about half of Canada’s population, with “close to half” of purchases made at international retail sites (International Trade Administration, US Department of Commerce 2018). Canada remains an outlier among the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries in not charging value-added tax on many e-commerce imports. This omission, which resulted in an estimated federal (-only) revenue loss of $169 million in 2017, places Canadian-based firms at a significant competitive disadvantage (Wyonch 2017; Auditor General of Canada 2019). Quebec and Saskatchewan extended their sales-tax bases to cover such transactions, including the electronic transmission of services, in 2018. Moreover, tax collection on relatively low-value shipments by courier firms and Canada Post remains inconsistent.

These developments have taken place during a period of continuing policy changes to international trade, investment, and border management. However, more recent events signal a serious potential for the disruption of the international trading system on which Canada relies for relatively predictable, rules-based market flows within and beyond North America in recent decades. These developments have greatly increased the unpredictability of administrative processes governing border management related to market flows within and beyond North America.

International Disruptions and Border Management

Episodic or the Wave of the Future?

Border management is subject to periodic shocks which reveal vulnerabilities and limitations within existing institutions and processes for managing risks, interactions among states, and between states and societal actors. The terrorist attacks and fallout of 9/11 revealed one such set of vulnerabilities; the 2020 global pandemic has exposed others. Other significant shocks of recent years include public-health risks associated with international travel (e.g., the severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, epidemic of 2003; Kirka 2020), food safety and animal health (e.g., bovine spongiform encephalopathy [BSE or mad-cow disease], avian flu, porcine epidemic diarrhea, and African swine fever). Central government agencies have been more effective in coordinating cross-border prevention, response plans, and measures on food safety than external public-health threats (Baxi and Sheer 2019; Panetta 2020). Societal disruptions, civil conflicts, and humanitarian disasters leading to mass international migration have severely disrupted national and regional societal consensus conducive to effective immigration and immigrant-integration policies in both the United States and Europe. However, pandemic-related travel disruptions, including the closure of some Canadian consular offices abroad, have also reminded broader publics of the extent of Canadian farmers’ dependence on temporary foreign workers for the planting and harvesting of many crops (Grant 2020).

North American and wider international trade regimes have been subject to repeated shocks in recent years as the governments of its largest trading partners, the United States and China, have resorted to unilateral actions to link major trade restrictions to growing geopolitical competition and ongoing trade negotiations. Major examples include the use (or misuse) of so-called national-security tariffs on steel and aluminum under section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act of 1962, with a view to extorting agreement to managed trade regimes for these commodities (Parkinson 2018), and the Trump administration’s disabling of the World Trade Organization’s dispute-resolution mechanism by blocking the appointment of new members to its appellate body (Fiorini et al. 2019), despite EU and Canadian efforts to create an alternative process. In 2019, China’s blockade of Canadian canola exports was widely seen as linked to Canada’s prospective extradition of a senior Chinese Huawei executive to face criminal charges in the United States (Vanderklippe 2019). In turn, these issues are linked to widespread allegations of intellectual property theft, cyber crime, and forced technology transfer. Taken together, these and other developments point to a growing breakdown of the rules-based global trade regime, and the spilling over of great power conflicts to the detriment of smaller countries such as Canada. These trends, combined with uncertainties related to the effects of the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) implementation and the COVID-19 pandemic, have significant microeconomic implications for the predictability and security of cross-border trade flows and international investment decisions.

However, trade is primarily a sectoral and firm-specific phenomenon. Border measures and practices, including tariff, non-tariff, and other administrative measures, are generally dependent variables whose relative importance varies with the relative intensity and market concentration of trade relations for particular sectors, sub-sectors, and firms. Several major sectoral measures, reinforced by the interdependence of cross-border supply chains, are contributing to the uncertainties noted above.

Automotive Sector

CUSMA’s multiple rules-of-origin provisions will increase the complexity and unpredictability of customs administration for thousands of products, even before their interaction with other US and Canadian trade agreements. Higher regional- and labour-value-content rules are designed to repatriate production and supply chains to higher-cost facilities in the United States and Canada. Company-specific costs will vary depending on their location within firm- and product-specific supply chains, and the interaction of these rules with environmental rules and technological shifts contributing to ongoing changes in production patterns and the location of assembly plants within North America (Alanis et al. 2018). Political conflict in the United States over fuel-economy standards deepens uncertainties for Canadian producers, complicating Ottawa’s efforts to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions since Canadian standards have increasingly aligned with tighter California rules (Bubbers 2020).

Steel and aluminum

Tit-for-tat retaliation for section 232 tariffs noted above greatly complicated producer- and region-specific variations in supply chains, which vary widely across steel-fabricating sub-sectors and downstream applications. These measures led Ottawa to introduce duty-remission measures for particular components, anti-dumping safeguards on others, and exemptions for specific projects dependent on foreign steel or fabricated components—including proposed liquefied-natural-gas terminals on Canada’s Pacific coast, whose economic viability depends on importing major component assemblies from the Far East (McCarthy, Jang, and Hunter 2018; Reuters 2018). Retaliatory tariffs imposed by countries targeted by US tariffs have had trade-diversion effects for other sectors, particularly agri-food (Powell 2018). American steel producers and fabricators also have access to complex, discretionary duty-remission programs, which applied to 57 percent of the value of previous Chinese imports in 2019, increasing supply-chain complexity and unpredictability (Lardner and Fenn 2019). New rules of origin introduced under the May 2019 metals-tariff agreement to limit supplies from outside North America will increase costs of border administration for fifty-four different categories of steel and aluminum imports (Morrow and Martin 2019).

Aeronautics and aerospace

The aeronautic and aerospace sectors have long been subject to political forces to promote local production, even if integrated within international supply chains, to access domestic markets often dominated by national or regional champions (Hartley 2014; O’Connell and Lamothe 2019). Boeing’s use of American trade- remedy laws to block Bombardier’s expansion into US regional jet markets in 2017–2018 ended with the latter’s negotiation of a joint venture with EU giant Airbus to manufacture C-Series jets destined for the United States in one of the latter’s American plants and market them through its global network (VanPraet 2017). The Quebec government later assumed Bombardier’s ownership share as part of the troubled company’s broader global retrenchment (Authier 2020). Ever-tighter US rules govern strategic materials and numerous “dual use” technologies with security-related applications (Hunter 2017; Alper 2020). Extraterritorial applications of US national-security regulations and/or mirroring Canadian rules for many aeronautic-related technologies, and in some cases personnel, have increased the challenges of managing international supply chains (Bourgeon and Vallet, forthcoming). These and other measures seriously affect bordering practices and related investment decisions. Indeed, while not decisive, their contribution to rising transaction costs and operating losses undoubtedly contributed to Bombardier’s attempted disposition of its commercial-aircraft-manufacturing assets in 2018–2020 (Reguly 2019; Jackson 2020).

Agri-food

Bordering regimes for primary commodities vary substantially across commodities and national borders, although they remain restrictive concerning supply-management regimes for dairy and poultry products. Regimes for processed food products outside these sectors have benefited from mutual-recognition agreements between US and Canadian regulatory agencies (Hale and Bartlett 2019). There has been extensive parallelism in sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regimes which deal with food safety and human and animal health since the 1990s, facilitating cooperation after detection of BSE closed national borders to cattle trade in 2003–2005. Food-safety systems remain distinctly national and vulnerable to politicization, as reflected in protracted (2006–2015) disputes over US mandatory country-of-origin labelling for fresh meat and other products, and Chinese customs measures noted above.

Canadian policy-makers have sought to promote science-based SPS regimes in market-access negotiations with European and Asian countries. However, the persistence of national differences (noted in chapter 8 here), often anchored in different consumer preferences, cultural attitudes, and historical concerns, has contributed to national market segmentation of food-processing facilities for certain commodities and the spread of market-driven standards in others, such as bans on genetically modified potatoes and certain veterinary drugs by the North American fast-food industry. Canadian livestock sectors have taken extensive measures ranging from expanded tracing protocols to cross-border cooperation with US producer groups to reduce and manage risks of animal disease outbreaks. Canadian and US regulators work together closely to reduce the safety risks of food products within and beyond North America through the bilateral Regulatory Cooperation Council (Carberry 2018; Hale 2019b). However, Canadian producers remain vulnerable to unilateral regulatory shifts and arbitrary administrative actions, increasing border-related uncertainties in international trade.

Shifting Borders and Human Movements

An orderly immigration policy capable of serving Canada’s economic needs, enabling immigrants to integrate effectively and prosper as full members of Canadian society, address regional variations in economic and social conditions, and adjudicate disputed cases fairly, has been critical to maximizing benefits from immigration while avoiding the kinds of social polarization which have divided many industrial societies, not least the United States. Translating these goals into effective, responsive border management is critical to their success.

Canadian governments took extensive steps in the early 2010s to address previous immigration-related border concerns. Some of these concerns, such as long waiting periods for prospective immigrants due to internal administrative inadequacies, were partially addressed by administrative reforms to expedite applications under the Harper governments. Expedient workarounds, such as the expansion of temporary foreign worker (TFW) programs after 2006, created problems when some employers were found to be recruiting (and sometimes exploiting) TFWs at the expense of domestic workers during labour shortages in the mid-2010s (Harper 2018). By contrast, immigrants selected under provincial nominee programs appear to have better labour-market outcomes than other “economic class” immigrants (Mueller 2019). Such policies are aimed primarily at socio-economic groups with sufficient financial, occupational, and/or educational resources to integrate effectively in Canadian society.

Imposing stricter conditions on TFW recruitment has created other pressures in areas of ongoing labour shortages, particularly in Quebec. It has also created renewed opportunities for unscrupulous immigration consultants, a long-standing problem, to exploit migrant workers through various forms of labour trafficking (Tomlinson 2019), prompting calls for tighter regulation of consultants. Canadian farmers’ frequent dependence on TFWs to maintain Canadians’ food security, noted above, impose corresponding obligations (and needs for enforcement capacity) for workers’ occupational health and safety (Grant 2020).

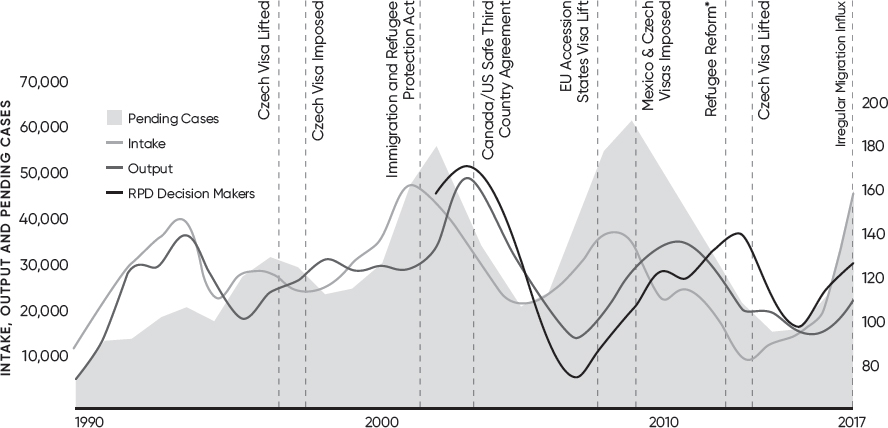

Canada’s international commitments under the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention, along with constitutional requirements for oral hearings and an independent appeals process for all asylum seekers within Canada, have created periodic challenges of border management when large numbers of economic migrants seek refugee status, whether at or beyond regular ports of entry. Annual volumes of asylum claims vary widely, depending on international conditions and federal visa requirements for travellers from countries with above-average rejection rates. Almost 500,000 applicants were refused temporary residence visas in 2017 (York and Zilio 2018). Periodic spikes in Immigration Review Board caseloads—57,000 in 2002 and 62,000 in 2009 resulting from increases in irregular migration—led to changes in federal legislation and administrative practices to reduce the backlog (Yeates 2018, 10–12, fig. 2.2).

However, a combination of “pull” and “push” factors contributed to another border shock in 2017–2018. Fears of the Trump administration’s proposed withdrawal of temporary protected status (TPS) from hundreds of thousands of US residents originally from Haiti, Central America, and other disrupted societies, reinforced by sometimes inaccurate social-media information on ways to “game” Canadian immigration laws by entering outside conventional ports of entry in pursuit of asylum resulted in the arrival of more than 2,700 irregular migrants entering Canada monthly during the second half of 2017, with smaller volumes in 2018–2019. Most took the well-travelled Roxham Road route across the New York–Quebec border into the waiting arms of the RCMP. Table 2.4 summarizes asylum claims over 2011–2019, noting the effects of the surge outside conventional ports of entry. Overall asylum claims rebounded in the second half of 2019, but without disproportionate changes in irregular migrants across land borders.

The largest number of migrants, spurred by widely available social-media information and easy access to US visitor visas, was from Nigeria (Nasser 2018). The influx overwhelmed federal refugee-processing resources, along with available housing in the Montréal and Toronto areas. Estimated and projected federal costs have averaged $365 million annually since 2017, not including unbudgeted effects on provinces (Zilio 2018; Curry and Zilio 2018). Measures introduced in the 2019 federal budget may “stabilize” the two-year backlog in Immigration and Refugee Board hearings by 2021, but additional policy changes will be needed to expedite review processes and significantly reduce existing backlogs (Forrest 2019). Pending cases in December 2019 totalled 87,270 (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada 2020).

Table 2.4. Asylum Claims: General Claims vs. Outside Ports of Entry, 2011–2019

|

Total Asylum Claims (/month) |

vs. 2012–20 Average (=100) |

RCMP Interceptions beyond POEs |

RCMP as % of total |

2011 |

2,109.6 |

167.8 |

||

2012 |

1,705.8 |

135.7 |

||

2013 |

863.8 |

68.7 |

||

2014 |

1,120.0 |

89.1 |

||

2015 |

1,338.3 |

106.5 |

||

2016 |

1,989.2 |

158.2 |

||

1–2 Q/2017 |

3,074.2 |

244.6 |

729.2 |

23.7 |

3–4 Q/2017 |

5,323.3 |

423.5 |

2,703.0 |

50.8 |

1–2 Q/2018 |

4,203.3 |

334.4 |

1,790.7 |

42.6 |

3–4 Q/2018 |

4,966.7 |

395.1 |

1,445.8 |

29.1 |

1–2 Q/2019 |

4,454.2 |

354.5 |

1,117.8 |

25.1 |

3–4 Q/2019 |

6,220.0 |

495.0 |

1,632.7 |

26.2 |

Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (2020).

Source: Neil Yeates (2018), Report of the Independent Review of the Immigration and Refugee Board. Ottawa: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 12. Courtesy of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

* Balanced Refugee Reform Act/Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act.

Extensive cooperation between Canadian and US authorities has resulted in the curtailing of US visitor visas to Nigerian travellers deemed “high risk” (Leuprecht and Hale 2019)—adding a new dimension to the concept of “pushing out the border.” In early 2019, the federal government formally requested revisions to the STCA to extend its provisions to the entire length of the US border, not just ports of entry (Zilio and Morrow 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic provided subsequent political cover for closing this loophole in 2020.

An additional measure that could allow more efficient use of resources would be to reinstate section 41 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) regulations—the so-called direct-back provisions. Such action would allow persons at significant risk to apply for refugee status from within the United States if not otherwise covered by STCA provisions. Such measures would provide a safety valve in case of changes to TPS provisions likely to create significant risks of another surge in irregular migration. However, such measures would need to be integrated with changes to STCA providing for a standstill in prospective US deportation proceedings for persons awaiting a Canadian refugee hearing. Implementation would also require safeguards to clarify the categories of persons at risk to preserve the benefits provided by STCA in providing effective “triage” of claimants from third countries (Leuprecht and Hale 2019).

The wide range of border-management issues addressed in this chapter requires persistent cooperation between governments and major stakeholders within and beyond Canada amid ongoing uncertainties. Border agencies have no control over trade negotiations, although the Canada Border Services Agency exercises discretion in applying trade-remedy provisions related to alleged dumping or illegal government subsidies of imported goods.

Continuing to improve clarity and consistency of border-related administrative procedures such as ACI and ACE remains critical for many businesses, especially smaller firms. Border agencies should continue to work toward single-window processes for trusted-trader programs and the continued streamlining of customs’ processes. However, given the diffusion of focus that often accompanies prolonged efforts at international regulatory cooperation, Canadian policy-makers should seek to “renew and reboot” the beyond-the-border process after the 2020 US presidential election, following consultation with major commercial and societal stakeholders. Meanwhile, federal agencies should take all necessary measures to implement the 2015 preclearance agreement in preparation for enabling its effective application to cargo shipments.

Growing interdependence in agri-food trade requires additional efforts to develop and implement emergency preparedness and response protocols for highly contagious animal diseases such as bovine tuberculosis and African swine fever in close cooperation with national, provincial, and state agri-food producers and processors, and with trucking interests on both sides of the border.

The federal government should continue to pursue revisions to the STCA with the United States to extend its jurisdiction to irregular migrants entering Canada outside regular ports of entry and accommodate reinstatement of IRPA section 41 provisions noted above. Although such measures could address public concerns over irregular migration and the related overloading of social services and refugee adjudication processes, it remains vital for governments to follow through in deploying increased resources to provide for fair and efficient hearings, while providing adequate protection for applicants whose physical safety would be substantially at risk in the event of deportation to their countries of origin.

Stable, long-term federal funding and continued federal/provincial (and related municipal) cooperation remain critical to leveraging ongoing private-sector investment in infrastructure related to major ports, inland gateways, and related corridors. However, improved regulatory coordination of infrastructure permitting, environmental, and land-use policies, including those involving Indigenous communities, remains critical to reducing bottlenecks in the renewal and upgrading of border and corridor infrastructure.

Challenges facing border management are evolving and dynamic, and typically build on existing initiatives. Existing cross-border processes provide opportunities to identify ongoing opportunities for cooperation. However, they require ongoing intergovernmental cooperation and societal engagement on both sides of the border to maintain or strengthen the commitment of governments to make the most of such resources.

References

Alanis, D., D. Burke, B. Collie, M. Gilbert, A. Jentzsch, C. Knizek, S. Komiya, J. Lee, and M. McAdoo. 2018. “Preparing for North America’s New Auto Trade Rules.” Boston Consulting Group, November 1. https://www.bcg.com/en-ca/publications/2018/preparing-north-america-new-auto-trade-rules.aspx.

Alper, Alexandra. 2020. “US Officials Agree on New Ways to Control High-Tech Exports to China.” Globe and Mail, April 1, 2020.

American Association of Port Authorities. 2020. Port Industry Statistics. https://www.aapa-ports.org/unifying/content.aspx?ItemNumber=21048.

Angus Reid Institute. 2017. “Airport Privatization: Canadians Not Prepared to Clear this Idea for Takeoff.” April 26, 2017. http://angusreid.org/airport-privatization/.

Auditor General of Canada. 2019. Report # 3 – Taxation of E-Commerce. 2019 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada. https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201905_03_e_43340.html.

———. 2016. Report # 1 – Beyond the Border Action Plan. 2016 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada. https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201611_01_e_41830.html.

Authier, Phillip. 2020. “A220 Sell-Off a Win-Win, Says Quebec Government.” Financial Post, February 14, 2020, FP3.

Bourgeon, M., and É. Vallet. Forthcoming. “US International Trade in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and Quebec’s Aerospace Industry.” In Borders in Motion: Canada’s International Policies in an Age of Uncertainties, edited by G. Hale and G. Anderson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bubbers, Matt. 2020. “What Do Trump’s Rollback of Fuel Economy Standards Mean for Canadian Drivers?” Globe and Mail, January 20, 2020.

Carberry, R. 2018. “Making a Good Thing Better: Finishing What Was Started and Leveraging NAFTA to Advance Canada-US Regulatory Cooperation.” Wilson Center. NAFTA and USMCA Resource Page, March 9. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/making-good-thing-better-finishing-what-was-started-and-leveraging-nafta-to-advance-canada.

Curry, Bill. 2018. “Federal Government Postpones Study of Airport Privatization.” Globe and Mail, April 21, 2018.

Curry, Bill, and Michelle Zilio. 2018. “Ottawa’s Bill for Asylum Seekers Could Top $1 Billion: PBO.” Globe and Mail, November 30, 2018, B1.

Eagles, M. 2018. “At War over the Peace Bridge: A Case Study in the Vulnerability of Binational Institutions.” Journal of Borderland Studies (May 4). https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2018.1465354.

Fiorini, M., B. Hoekman, P. Mavroidis, M. Saluste, and F. Wolfe. 2019. “WTO Dispute Settlement and the Appellate Body Crisis: Insider Perceptions and Members’ Revealed Preferences.” VOXEU.org. CEPR Policy Portal, November. https://voxeu.org/article/wto-dispute-settlement-and-appellate-body-crisis.

Flynn, S. E. 2003. “The False Conundrum: Continental Integration vs. Homeland Security.” In The Rebordering of North America: Integration and Exclusion in a New Security Context, edited by P. Andreas and T. J. Biersteker, 110–127. New York: Routledge.

Forrest, Maura. 2019. “Asylum-Claim Backlog could Hit 100,000 by 2021.” National Post, May 29, 2019, A4.

Goodale, R. 2019. “Remarks by Minister Goodale at the Annual Summit of the Pacific NorthWest Economic Region.” Public Safety Canada. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, July 24, 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-safety-canada/news/2019/07/remarks-by-minister-goodale-at-the-annual-summit-of-the-pacific-northwest-economic-region.html.

Grant, Tavia. 2020. “Crops in Peril as Temporary Foreign Workers Yet to Arrive.” Globe and Mail, April 2, 2020, A1.

Hale, G. 2019a. “Cross-Border Energy Infrastructure and the Politics of Intermesticity.” In Canada–US Relations: Sovereignty or Shared Institutions, edited by D. Carment and C. Sands, 163–192. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

———. 2019b. “Regulatory Cooperation in North America: Diplomacy Navigating Asymmetries.” American Review of Canadian Studies 49 (1): 123–149.

———. Forthcoming. “Managing Interdependencies: Assessing Cross-Border Transportation and Infrastructure Regimes in a North American and International Context.” In Borders in Motion: Canada’s International Policies in an Age of Uncertainties, edited by G. Hale and G. Anderson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Hale, G., and C. Bartlett. 2019. “Managing the Regulatory Tangle: Critical Infrastructure Security and Distributed Governance in Alberta’s Major Traded Sectors.” Journal of Borderland Studies 34 (2): 257–279.

Hale, G., and C. Marcotte. 2010. “Border Security, Trade and Travel Facilitation.” In Borders and Bridges: Navigating Canada’s Policy Relations in North America, edited by M. Gattinger and G. Hale, 100–119. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Harden-Donahue, A. 2017. “From NIMBY to NOPE: Protecting Climate and Water from Tar Sands Pipelines. Council of Canadians. Analysis, September 13, 2017. https://canadians.org/analysis/nimby-nope-protecting-climate-and-water-tar-sands-pipelines.

Hartley, K. 2014. The Political Economy of Aerospace Industries. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Hunter, A. P. 2017. “The Promise and Peril of Protectionism in the Defense Sector.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. Commentary, July 14, 2017. https://www.csis.org/analysis/promise-and-perils-protectionism-defense-sector.

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 2020. “Refugee Protection Claims (New System), by Country of Alleged Persecution—2019.” Refugee Protection, February 20, 2020. https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/statistics/protection/Pages/RPDStat2019.aspx.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2020. “Asylum Claims by Year.” Immigration and Citizenship. Refugees and Asylum. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/asylum-claims.html. International Trade Administration, US Department of Commerce. 2018. “Canada: E-Commerce.” December 18, 2018. Last modified September 30, 2019. https://www.export.gov/apex/article2?id=Canada-eCommerce.

Jackson, Emily. 2020. “Sold – Dismantling Bombardier.” Financial Post, February 14, 2020, FP1.

Kirka, Danica. 2020. “A British Business Traveler May Have Transmitted Coronavirus Across Multiple Countries.” Time, February 1, 2020.

Lardner, Richard, and Larry Fenn. 2019. “Hundreds of US Companies Excused from Tariff on Steel from China, Other Countries, Despite Trump’s Tough Talk.” Globe and Mail, February 15, 2019.

Leuprecht, Christian, and Geoffrey Hale. 2019. “Submission to House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration re: Bill C-97.” Macdonald-Laurier Institute, May 7, 2019. https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/files/pdf/CIMM%20submission%20C-97%20Leuprecht%20Hale%207%20May%202019.pdf.

Lynch, Kevin, and Paul Deegan. 2020. “Five Lasting Implications of COVID-19 for Canada and the World.” Globe and Mail, April 2, 2020, B4.

McCarthy, Shawn, Brent Jang, and Justine Hunter. 2018. “Ottawa Clears Way for Proposed LNG Terminal on BC Coast.” Globe and Mail, September 26, 2018, A1.

Morrow, Adrian, and Lawrence Martin. 2019. “Canada, US and Mexico Reach Deal to Lift Trump Administration’s Steel and Aluminum Tariffs.” Globe and Mail, May 17, 2019.

Mueller, Richard E. 2019. “Enhancing Labour Supply and Mobility in Alberta: The Role of Immigration, Migration, and Developing Existing Human Capital.” Parkland Institute. Report, June 17, 2019. https://www.parklandinstitute.ca/the_future_of_albertas_labour_market.

Nasser, Wael. 2018. “Irregular Border Crossings and Asylum in Canada: Study on the Irregular Migration from Nigeria to Canada.” Undergraduate honours thesis, Department of Geography, University of Lethbridge.

O’Connell, Jonathan, and Dan Lamothe. 2019. “Nation’s Close Ties with Boeing Draw Fresh Attention.” Washington Post, March 17, 2019, A1.

Parkinson, David. 2018. “Canada Opposes Replacing US Tariffs with Quota System, Freeland Says.” Globe and Mail, October 20, 2018.

Powell, Naomi. 2018. “Soybean Farmers Caught in China vs. US Tariff Row.” Financial Post, July 11, 2018, FP1.

Reguly, Eric. 2019. “A Family Affair: The Dismantling of Bombardier.” Globe and Mail, June 8, 2019, B4.

Reuters. 2018. “Canada Drops Tariff on US Made Aluminum Cans as Beer Makers Face Shortage.” Globe and Mail, October 18, 2018.

Rienas, Ron. 2019. “Pre-Arrival Readiness Evaluation (PACE) at the Peace Bridge.” Presentation to PNWER Border Session, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, July 22, 2019.

Saltman, Jennifer. 2020. “Rail Blockades Deepen Backlog at B.C.’s Ports.” Vancouver Sun, February 25, 2020, A1.

Savage, Luisa Ch. 2015. “Why Canada Is Paying $4 Billion for a New Detroit-Windsor Bridge.” Maclean’s, May 22, 2015.

Smith, M. J., S. B. Ray, A. Raymond, M. Sienna, and M. B. Lilly. 2018. “Long-Term Lessons on the Effects of Post-9/11 Border Thickening on Cross-Border Trade Between Canada and the United States: A Systematic Review.” Transport Policy 72 (C): 198–207.

Stana, R. M. 2008. Various Issues Led to the Termination of the United States-Canada Shared Border Management Pilot Project, GAO-08-1038R. US Government Accountability Office. Report, September 4, 2008. https://www.gao.gov/assets/100/95717.pdf.

Statistics Canada. 2019a. “International travellers entering or returning to Canada, by type of transport.” Table: 24-10-0041-01 (formerly CANSIM Table 427-0001). Data, April 1, 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=2410004101

———. 2019b. “Balance of International Payments, Current Account and Capital Account, Annual.” Table: 36-10-0007-01 (formerly CANSIM Table 376-0036). Data, March 1, 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610001401.

Tomblin, S. Forthcoming. “Cross-Border Constraints and Dynamics in the Northeast.” In Borders in Motion: Canada’s International Policies in an Age of Uncertainties, edited by G. Hale and G. Anderson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Tomlinson, Kathy. 2019. “False Promises: Foreign Workers are Falling Prey to Sprawling Web of Labour Trafficking in Canada.” Globe and Mail, April 6, 2019, A15–17.

Vanderklippe, Nathan. 2019. “China Ramps Up Tensions, Halts New Purchases of All Canadian Canola, Imports Strict Inspections of Other Agricultural Goods.” Globe and Mail, March 23, 2019, B1.

VanPraet, Nicolas. 2017. “How Airbus Landed Bombardier’s C Series.” Globe and Mail, October 18, 2017, B1.

Wilson-Raybould, Jody. 2020. “Who Speaks for the Wet’suwet’en People? Making Sense of the Coastal GasLink Conflict.” Globe and Mail, January 25, 2020.

Wyonch, Rosalie. 2017. “Bits, Bytes and Taxes: VAT and the Digital Economy in Canada.” C.D. Howe Institute Commentary No. 487 (August). https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Commentary_487.pdf.

Yeates, Neil. 2018. Report of the Independent Review of the Immigration Review Board: A Systems Management Approach. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, April 10, 2018. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/pdf/pub/irb-report-en.pdf.

York, Geoffrey, and Michelle Zilio. 2018. “Access Denied: Canada’s Refusal Rate for Visitor Visas Soars.” Globe and Mail, July 9, 2018, A1, A8–A9.

Zilio, Michelle. 2018. “Asylum-Seeker Surge at Quebec Border Chokes Refugee System.” Globe and Mail, September 12, 2018, A1.

Zilio, Michelle, and Adrian Morrow. 2019. “Canada, US Move to Redraft Border Treaty to Cut Flow of Asylum Seekers.” Globe and Mail, April 1, 2019, A1.