8

Safety First Because Safety Lasts

From GECO’s outset, their mandate was clear: “Scarboro was conceived, constructed, organized and operated for but one purpose — PRODUCTION — and to that end every department of The General Engineering Company (Canada) Limited made direct or indirect contribution.”1 Even the safety of its employees did not take precedence over production at a time when countless lives might be sacrificed for lack of dependable ammunition.2

Despite the Hamiltons’ declaration that production reigned supreme, Bob, Phil, and their cohorts consciously, or perhaps even more so unconsciously, made safety one of their highest priorities. The protection of GECO’s assets was an ever-present and solemn concern for GECO management.

Monday morning quarterbacks — critics who lament their game could have been won had someone made a different play — may have coined the expression “hindsight is 20/20.” While bulldozers and 2,500 strong Canadian men worked around the clock to build GECO, no one could predict the duration or outcome of a world at war, just as they had no way to foretell what ultimate cost Scarboro might pay through the loss of life or limb due to explosion. They did have control, however, over the decisions they made. From the earliest whispers of bringing a top-secret munitions plant to Scarboro, to the last fuse filled, from plant design to safe working practices, from minimizing static electricity to strongly reminding wayward or negligent employees, every decision made, not only during construction but throughout the life of the plant, was first and foremost tested against a consummate safety standard. There could be no room for regret.

Scarboro’s employee safety record was rare and perhaps without equal in global munitions handling.3 GECO management attributed this success primarily to attentive care spent on eliminating the chance of fire and explosion and to minimizing the damage of such incidents if they did happen.4 Experts in munitions would likely attribute Scarboro’s stellar safety record — and they would face little if any opposition — to GECO’s dynamic duo, Bob and Phil, and their safety officer, George M. Thomson, for not only their exemplary vision but also their conscientious and fastidious operating procedures.

The Hamiltons ultimately were responsible for the plant’s safety; Safety Officer Thomson reported directly to them.5 He managed all aspects of safety at the plant. His mandate included managing inspectors, maintaining safe limits in storing explosives, overseeing the entire Security Department, and ensuring proper ventilation, lighting, and humidity.6

Safety, of course, was a dominant consideration in ammunition filling in general in the United Kingdom, and in fuse filling in particular. The finished “product” was only as perfect as the many steps to prepare and fill the fuse. It had to be free from filings, grit, or other superfluous material that might disturb the delicate mechanism or agitate the explosives in the weapon.7 Dirt could cause friction; static electricity might cause a spark. Both had the potential for catastrophic explosions that might not only disrupt production of critically needed war supplies, but could endanger the lives of thousands of employees. GECO did not want to repeat the tragic accidents experienced at other munitions plants during the Great War, where five fatal accidents occurred at Hayes, the plant from which GECO was patterned.8 In addition, there had been four deaths from toxic jaundice at that munitions plant, bringing the total death count to nine.9

W.H. Pitcher wrote of Scarboro, “In designing this plant, safety has been the primary consideration — safety not only for its four to five thousand employees working on 8-hour shifts, but safety combined with efficiency to turn out the greatest number of completed fuses in the shortest possible time.”10

From protecting the physical plant to building and workshops, from galleries and tunnels to the hazards of working with tetryl, safety and efficiency was foremost on everyone’s mind.

Friend or Foe?

All interested parties agreed — buildings at GECO were to have a low profile, built mostly as single-storey workshops.11 The plant was to remain as inconspicuous as possible from the ground and air. Of course, this mandate was not as easy to carry out when thousands of yards of eight-foot-high barbed-wire fence surrounded the complex, but for the most part, even from neighbouring farms, GECO could not be seen other than perhaps for its smokestack.

In addition to the barbed-wire fencing, the site was heavily guarded, with access restricted to a handful of entry points.12 If, by some chance, a lost motorist came upon GECO unaware of what went on inside the intimidating military installation, he more than likely would have been quickly approached, challenged, and then escorted away by GECO’s armed security personnel.

Older army men comprised 80 percent of the plant’s security force, and their mandate was simple: keep undesirables out.13 Successful applicants to the force had a background in police or military service, and had to clear an extensive background check.14 The Commissioner of Provincial Police swore in each guard as a Special Constable.15

Armed guards patrolled the property continually, one guard responsible for between 350–500 yards of property.16 Special Fence Patrols traversed the entire perimeter of the plant, consisting of over 347 acres, one lap of which took about an hour to complete.17 The guards patrolled the plant, rain or shine, fair or foul weather, even during blizzards and bitterly cold blustery days.

Each shift included a parade for duty, roll call, and uniform and area inspections.18 In addition to patrolling the site and keeping “a vigilant watch for possible sabotage,”19 guards were also responsible for fingerprinting, photographing, and checking letters of reference for all new employees, supervising loading and unloading of buses, being on hand at the bank on payday, and maintaining a “lost and found” area.20 Special Security Observers, both male and female, were present in change rooms to ensure no prohibited material was transported onto the clean side of the plant.21

GECO commenced keeping guard statistics early, while still under construction. By July 1, 1941, twenty-three men walked the site twenty-four hours a day.22 When construction wound down and production ramped up, so did the number of men hired to protect the plant’s assets, interests, and employees. Eighty guards secured the site by the end of 1942, with a healthy aggregate of more than seventy men protecting GECO until the end of the war.23

As for employees, guards demanded they present valid ID pass cards before entering the compound.24 All employees were subject to a physical search of their belongings and person.25

In addition, all employees understood anti-sabotage procedures and participated in air-raid drills,26 and air-raid alarms were installed on all buildings.27

In Case of Explosion …

Running a top secret munitions plant with thousands of workers who handled high explosives meant incorporating extraordinary fire and explosion prevention strategies and emergency processes into its design, construction, and operation. A considerable water supply was imperative, including a regular supply from Scarboro Township’s water main, two domestic water storage tanks of 250,000 gallons each, and an open water reservoir with a capacity of 2.5 million gallons.28 More than five hundred fire extinguishers were placed strategically throughout the compound, including the extensive gallery and tunnel systems.29 Indoor hoses — totalling more than two-and-a-half miles — were installed in all buildings and galleries.30 Fifty-five outdoor hydrants were installed at regular intervals around the plant, including four-and-a-half miles of hose.31 Twenty-six guards’ stations were set up within the tunnel system.32 Fire safety guidelines were taught to and enforced by all employees, and fire drills were held weekly at first, then bi-monthly throughout the duration of the war.33 Smoking was allowed only on the dirty side of the plant because of the inherent fire hazard associated with matches and smouldering cigarette butts.

“Scarboro” possessed two fully functioning fire halls.34 The larger hall in Building No. 90 was located on the dirty side of the plant close to the medical building, situated in the northwest area of the complex.35 An auxiliary hall was housed in Building No. 145 at the southern end near the Proof Yard.36 Fire Chief T. Benson was in charge of all auxiliary fire areas.37 Before the Second World War there was only one fire hall in Scarboro Township, located on Birchmount Avenue north of Kingston Road.38 The plant boasted the largest industrial fire department in the country, and the largest of any kind in Ontario, yet the only fires the brigade handled were doused with a bucket of sand before firefighters could arrive.39

Unique to its civilian counterparts, GECO sported blue fire trucks with flowers, perhaps as a salute to its predominantly female workforce, stencilled on the fenders.40 One, a converted Chevrolet, included a pump with a capacity of almost two cubic yards per minute, 460 yards of hose, six chemical extinguishers, and a ladder.41 The other, built onsite on a converted Ford chassis, contained a water pump that could pump two and one half cubic yards per minute, 351 yards of hose, six chemical extinguishers, and a twelve-yard extension ladder.42 Of almost thirty firemen on site — mostly retired Toronto firefighters — any man without thirty years of experience was considered a rookie.43 GECO’s fire detachment also comprised about one hundred volunteer firefighters who had other regular occupations in the plant.44

Neither hoses nor water were allowed in GECO’s expansive service tunnel system since the plant’s electrical infrastructure was located within its confines.45 Instead, Pyrene or carbon dioxide extinguishers were placed within the underground labyrinth.46 Should a fire occur in a branch off the main tunnels running north/south, in an underground switch room, or in a transformer vault, fire doors were closed to keep the fire contained belowground.47

In addition to keeping GECO structures to one storey, buildings were staggered and arranged with the hope that in case of explosion, damage and injury would be contained to one building.48 Structures, especially those that stored explosives, were constructed in a more scattered fashion toward the southern end of the plant.49 Vestibules running directly above the tunnel system and spanning the length of most buildings on the clean side alternated between the north and south sides of workshops.50 As for safe distancing between munitions buildings, the United States recommended a distance of six hundred feet.51 This was quite different from Britain’s recommendation of 100 feet between buildings.52 The plant’s First World War British counterpart, Hayes, built buildings only seventy-five feet apart.53 GECO management decided two hundred feet was reasonable to leave between factory buildings.54 A minimum of six hundred feet was maintained between plant buildings and main roads outside the plant.55

Ever fire-conscious, GECO engineers recommended weatherproof, fire-resistant “weatherboard” plywood to cover the outside of all buildings.56 It was available, cheap, and could be applied quickly.57

Buildings in the Danger Zone, where workers handled explosives, were divided into “shops” and separated by reinforced concrete or masonry firewalls three feet tall.58 Side walls were constructed from “flimsy wallboard,” as GECOnian Ernie Pickles recalls.59 “If an explosion occured [sic] it would not affect the next room down the hall,” he states, “but the explosion would knock down the side walls and dissipate to the outdoors.”60 In addition, heavy explosion/fire doors, operated via a robust pulley system, separated all buildings from “cleanways.”61 Escape doors in each fuse-filling shop to the outside offered a way out in an emergency.62 In total, over four hundred fire doors were installed throughout GECO’s buildings on the clean side.63

For easy manoeuvrability of munitions, machinery, and operators alike, fuse-filling shops enjoyed an almost forty-six-foot-wide free-span frame with no internal support beams.64 Buildings with no internal support could withstand an explosion that took out a large part of a wall or the roof without complete collapse.65 GECO’s ingenious solution to a scant or practically non-existent steel supply was to use their newly invented “super structure” or “timber beam.”66

Life Expectancy

GECO’s buildings were built with an estimated five years of useful life.67 It was felt that a global conflict of the Second World War’s magnitude could not possibly last more than a few years. Ironically, because GECO was a munitions factory, building construction and materials were often of a superior, stronger quality than normally would be expected in a temporary endeavour. In a short-term industrial undertaking, a rough and simple interior finish to inside walls typically would have been adequate. However, in GECO’s case, interior finishes had to be clean and smooth with no crevices that could collect dust.68 As well, maintaining a precise degree of heat and humidity in clean-side buildings was an absolute necessity and demanded extra care in construction.69 With a scarcity of steel during the war, GECO employed their “super structure” technology in shops, which expanded to tunnel ceilings, providing superior workmanship and longevity.70 As a testament to quality workmanship, almost seventy years past their end-of-use date several original GECO buildings remain today.

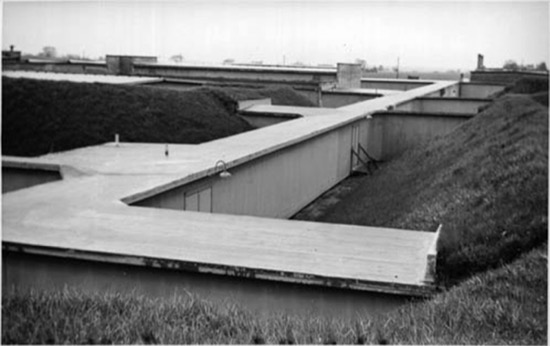

Special buildings called “magazines,” where a substantial quantity of explosives were stored, such as Building Nos. 48–55 or Building Nos. 81–85, were isolated from other structures.71 In some cases these magazines, nicknamed “igloos,” were partially or completely buried by dirt conveniently made available from excavating the tunnel system. This provided some additional protection to surrounding buildings should an explosion occur.72 Igloos were reinforced with concrete and steel as they were constructed.73 Later, when steel became scarce as construction continued, igloos were supported with “super structures.”74 Berms built from excavated tunnel dirt surrounded some clean-side buildings, to minimize potential damage of surrounding structures in case of explosion.75

In Spotless Air-Conditioned Shops

GECO engineers had to consider many things when building fuse-filling workshops in the Danger Zone, from heating and cooling to controlling humidity, from preventing dust accumulation to avoiding static electricity, as well as anticipating the potential devastation of worker error, carelessness, and neglect. GECO, as an arsenal, was expected to incorporate many safety fuse-filling procedures based on British experience that never before had been used in Canadian industrial practice.76 Conditions in Canada were quite different from those found in England, especially in coping with Canada’s northern climate.

Each fuse-filling building was separated into several “workshops,” each approximately 55 by 105 feet, and with each workshop having an “annex” measuring about 16.5 by 55 feet.77 Walls were painted ivory and the floors were covered with resilient and easily cleaned brown linoleum.78 Cleaners wiped down floors in some workshops every four hours. Walls, ceilings, and light fixtures in workshops were cleaned weekly.79

Static electricity was a munitions factory’s worst nightmare. In a closed environment where high explosives were in use, a buildup of accumulated electrons within a person’s body or metal-containing object could suddenly release and cause a “spark.” A single spark could ignite highly explosive or inflammable materials, causing a catastrophic chain reaction.80 GECO took extraordinary measures to prevent static electricity. Every piece of machinery on the clean side was grounded, and ground plates were placed at the door of each filling shop.81 “You had to touch it every time you went through,” GECOite Peter Cranston recalled. “It was a firing offence to forget.”82 The use of “super structures” in ceilings allowed for “tight” construction, minimizing dust.83 All cracks and joints in walls were filled and taped before applying an interior finish.84 Small dust-proof, explosion-proof push-button electric lighting was installed.85 Bronze and brass were used in place of other metals.86 Lightning rods were installed in all buildings.87 Electrical fixtures in GECO workshops were not to exceed a surface temperature greater than 60 degrees Celsius to eliminate the chance of explosion.88 Lighting in GECO’s workshops provided fifteen foot-candles intensity.89 Workshops were inspected at least once every shift.90

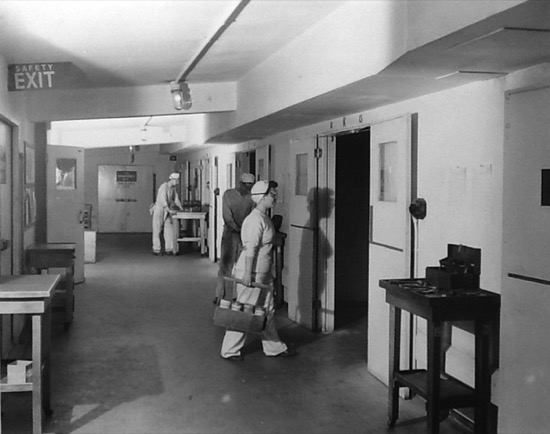

GECO’s gallery system was connected to corridors that ran alongside filling shops on the clean side. These vestibules conveyed both workers and ammunition and were kept rigorously clean. Ground plates, situated outside the doors to each workshop, were touched by every employee before they entered to minimize the risk of static electricity. A small tool crib sat in various vestibules to ensure quick repairs when appropriate. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

To minimize the chance of static electricity and sparks, work could only be carried out in filling shops where air humidity was kept within certain limits.91 GECO engineers and management mandated that humidity in workshops should be maintained at a constant 55 percent using an air conditioning system.92 Uniform humidity in workshops resulted in a higher quality final product — fuses that would execute perfectly when it mattered most.

“Early in the plant’s construction, the decision was made to erect buildings on the clean side without windows. This decision extended to the extensive gallery system. Windowless workshops sped up construction time; workers didn’t have to fuss over preparing walls for the installation of windows and sills, and there would be no interruption in construction should glass or materials be delayed or not be available.93 Fortuitously, windowless shops helped control humidity in hot, muggy weather and minimize condensation in damp winter months.”94

Keeping thousands of operators, predominately female, comfortable was a huge challenge. A central heating/cooling unit in each workshop maintained a comfortable twenty-two degrees Celsius.97 Fresh air was filtered in to each workshop every twelve minutes during summer months.98

W.H. Pitcher had this to say about GECO’s cleanliness: “Of perhaps equal importance in maintaining safe working conditions about the plant is good housekeeping. Every bench, every workshop, all the corridors and the working personnel are scrupulously clean.”99

Jack Be Nimble

GECO management used every opportunity to instill safety awareness in their employees, including communicating via their employee newspaper. Humour, poetry, and cartoons were often used to teach and remind employees of their responsibilities and the potentially deadly consequences should they lack diligence. One poem with its accompanying cartoon read:

Jack be nimble, Jack be quick,

Jack made eyes at a passing chick,

He teetered and tottered and finally fell,

Now we’re all waiting for Jack to get well.100

Transporting detonators, the most unpredictable of all munitions, required specially marked red boxes, carried by hand by a seasoned GECOite, his red cap a warning to all to give him lots of room to pass. The July 4, 1942 issue of the plant’s paper offered this reminder: “All the men wearing the dark red caps need the right of way — especially those with the scarlet wooden satchels. These satchels aren’t filled with cough drops …”101

Galleries, Tunnels, and More Tunnels, Oh My!

The expansive Scarboro site included an elaborate aboveground gallery network spanning more than three miles, and an extensive labyrinth of tunnels connecting most of the munitions facility’s buildings on the clean side.102

The First World War’s Hayes munitions plant in England, upon which GECO’s design was patterned, linked clean-side buildings with boardwalks — wood planks — laid out along the ground.103 Both walkways and workers were exposed to all weather conditions. Depending on the daily weather, women brought dirt, mud, soggy hair, and damp clothing into their workshops. The Hamilton brothers knew they needed a safer, cleaner way for GECO’s workers to travel to and from their shops. They decided to cover the plant’s “cleanways,” heat and air-condition them depending on the weather, keep them fastidiously clean, and attach them to the shift houses so workers would always be in an “All Clear!” state of mind.104

The expansive Scarboro site included an elaborate aboveground gallery network spanning more than three miles. Employees travelled to their respective fuse-filling workshops through these temperature-controlled, windowless, enclosed walkways. Berms surrounded some clean-side buildings to minimize potential damage to surrounding structures in case of explosion. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

At critical points in the covered corridors, workmen installed steel safety doors to prevent a potential fire from spreading through the complex via the hallways.105 To minimize the spread of fire or explosion, the points at which lateral galleries entered the main cleanways running north/south were offset.106 The engineering sketch of GECO depicts these offset cleanways and tunnels very well. For example, the entrances to the gallery system and tunnel system from Building No. 56 and No. 59 are staggered, not directly across from each other. If an explosion or fire occurred in one building, the hope was that it would be harder to spread to the building on the other side of the cleanway.

Canada’s governor general, the Earl of Athlone, husband to Her Royal Highness Princess Alice, remarked on a visit to the plant that the galleries were “long, spotless, wooden-floored halls, where employees marched smartly, avoiding such dangerous static-producers as dragging their feet or rubbing their hands along the walls.”107

Even more extraordinary than GECO’s unique aboveground gallery system was the extensive tunnel system that ran under the complex.108 The tunnels housed essential services like lines for water, electrical power, steam, and compressed air for the entire plant.109 Installing services below ground allowed maintenance and repairs to be carried out without disruption to workers in the workshops above or risking explosion by carrying out maintenance in sensitive fuse-filling shops.110 GECO’s tunnel system was byzantine, and even during construction workers were warned of the potential danger of losing their bearings while underground.111 All work was kept to short sections of tunnel. The tunnel walls were built from reinforced masonry blocks, tall and wide enough to easily accommodate skids of munitions.112 This type of construction could withstand shock and collapse should an explosion occur, and survive a potential cave-in due to seismic activity, similar to precautions taken in earthquake zones.113 The ceilings of the tunnels were made from two-by-eight-inch planks of local hardwood, turned on their thin sides, then nailed and glued, offering the same strength as “super structures” found in workshop ceilings.114 The honeycomb tunnel system, in desperate circumstances, could have been used to protect GECO’s employees from possible air raids, enemy invasion, and explosions, or provide an evacuation route. There is no oral or written record to ascertain if the tunnels were ever used for these purposes.

There is ongoing debate as to whether GECO situated washrooms in its tunnel system. According to Sidney Ledson and Philip Hamilton, two GECO employees, the tunnels were not accessible to workers.115 Furthermore, through interviews, several surviving female workers confirmed they had no knowledge of tunnels running under their feet. However, in GECO’s written account, it states: “… washrooms were situated inside, above, or adjacent to the service tunnels.”116 According to the 1956 Fire Insurance Plan of Toronto, there is a washroom seemingly underground, housed in Building No. 74.117 Logically, and despite the debate, while the tunnel system ran underground on the clean side, they were not “clean.” Accessing washrooms below ground would have rendered workers “dirty” and not fit to return to their shops. If there were washrooms located underground, they were used by maintenance workers only.

GECO’s extensive gallery and tunnel system were remarkable accomplishments. Even more extraordinary, a second tunnel system stretched out directly beneath the upper tunnels to house GECO’s plumbing infrastructure.118

Guns and Gum

In addition to the specific safety precautions taken in the design and wearing of her uniform, operators were trained in first aid, the use of fire extinguishers, expected to follow strict workshop regulations, and prohibited from carrying contraband onto the clean side of the plant.119 The list of prohibited items was extensive and demanded a good memory. “I forgot” was not an acceptable excuse.120 In fact, there was a zero tolerance policy for contraband found on any GECO employee. Contraband included food; drink; chewing gum; matches, or any other means of lighting a fire; any type of tobacco or snuff; any metal object such as keys, knives, scissors, watches, or loose change; any article made from silk or artificial silk in any form; and live animals.121

Dorothy Cheesman recalled that the list of banned items was much lengthier; they were not even allowed a deck of playing cards.122 Molly Danniels remembered they had to keep their fingernails short.123

Death and Disfigurement

While GECO suffered no fatal occupational accidents during its operation, inevitably, by the very nature of the work carried out at the plant, mishaps and explosions did occur.124 “We had a lot of small explosions,” Bob Hamilton recounted in a media interview.125 “The unit which gave us the most trouble was the tracer; a four-inch-long steel tube which fit in the bottom of a shell. When the shell is ejected, the heat ignites the tracer and you can see where it goes. Specs call for compressing the ignitable material almost to its breaking point. Occasionally there would be slag in the shell, and the compression would ignite it in the shell and there’d be a large flare in the shop; twenty-five women quit.”126 Molly Danniels confirmed Bob’s account; she was in the workshop when a blast occurred, and witnessed more than two dozen women walking out. Molly stayed.127

Another mishap, more serious, occurred when Assistant Forman P.W. Meaham “suffered severe injuries to his arms” while “proofing” filled munitions for quality assurance in the Proof Yard.128 After recovering, Mr. Meaham, perhaps appropriately, joined the Safety Department.129 Bob Hamilton recalls one big accident toward the end of the war after a night shift. “The head of the Proof Department was obviously tired and wanted to go home,” Bob said, “and he hurried up proofing a shell, a fuse it was, and it went off in his hands and practically blinded him.”130 Bob continues, “That was due to fatigue and a Saturday night wanting to get home. He broke three safety regulations in doing that. You do those things when you’re tired.”131 A cartoon ran in the newspaper warning clean-side employees: “Fingers do not grow on trees — watch what yours are doing, please.”132

An internal review of industrial relations at the plant took place mid-1943, with the following comment made in regards to GECO’s accident history: “The record of this Company in accident occurrence is low to an outstanding degree in comparison with other (including non-explosives) companies, throughout Ontario.”133

The Tetryl Dilemma

Munitions filling at GECO included using a yellow crystal-like concoction called tetryl, a highly sensitive explosive used in Britain and the United States during the First and Second World Wars. In its solid state, tetryl didn’t pose much of a hazard to GECO’s personnel — other than it being highly explosive — but when it was ground into a fine dust it became airborne, likely to settle on employee uniforms, caking their hands, and getting into their eyes and lungs. Tetryl had the potential to be highly toxic to some operators, and was a potent source of occupational illness.134 Severity of symptoms varied depending on the degree of exposure to the tetryl and how sensitive the operator was to its components.135 Symptoms included eye and skin irritation, including discolouration, or “yellow-staining,” of hands, neck, and hair, stomach upsets including nausea and diarrhea, cough, sore throat, upper respiratory wheezing and congestion, headache and fatigue, and nose bleeds.136 While it was not known if tetryl affected reproduction, a rumour circulated around the plant that women who worked with tetryl could not bear children.137

Bob and Phil Hamilton and their entire management team, including Dr. Jeffrey, GECO’s chief physician, recognized the potential hazard in working with tetryl. The First World War English munitions plant at Hayes (which GECO mirrored) recorded four deaths due to toxic jaundice.138 To minimize the hazards associated with tetryl, GECO management considered its effects in every decision made, even during the early days of construction. The toxic nature of airborne tetryl dust made it necessary to keep H.E. filling operations entirely separate from other areas in the plant. Only women who worked directly with tetryl were exposed to its potential toxins, not every employee.

During GECO’s initial hiring campaign, Dr. Jeffrey wrote that, “special attention was given to skin conditions and chronic respiratory ailments which might incapacitate operators working with tetryl.”139 Some women were hired to work solely on the G.P. line due to pre-existing conditions such as eczema or asthma, which, with repeated contact with tetryl, could endanger their health.140 Dr. Jeffrey noted later on that skin conditions were not as important as certain chronic respiratory ailments in choosing workers for tetryl filling shops.141

To further segregate operators who worked with tetryl, GECO set up a separate area in change houses where specific attention was given to uniforms needing more rigorous laundering and skin protection, including the application of special creams.142 Nursing staff were in attendance during shift changes to offer tetryl-related advice.143 Sue Szydlik, GECOite Irene Darnbrough’s daughter, remembers her mother using a cola soft-drink to wash off the yellow stains. “They would wash in it before leaving the plant.”144 Sylvia Nordstrand’s sister filled tracers. “She became all yellow, clothes and skin, and she never seemed to get rid of it until she left for any length of time, holidays, etc.”145 The methods used in GECO’s change rooms to manage tetryl rash became a standard for other munitions plants across Canada.146

The art of stemming — pressing a specified quantity of high explosives powders into certain areas within a fuse — caused a fine dust of tetryl to spread, and in spite of standard precautions taken, an inordinate number of women were exposed to its potential ill effects.149 Management decided that only specially selected operators who tolerated the effects of tetryl well would be assigned to stemming work.150 These operators worked from outside a hood or “lighthouse” that vented to the outside and could accommodate six or eight operators.151 When GECO first got underway, each filling shop did their own stemming according to English peacetime practices.152 However, as the war progressed, a dedicated stemming shop — “60B” — Building No. 60, Workshop B — was opened.153 Segregating and merging these two operations helped confine tetryl dust to one location and greatly reduced the incidence of rash and tetryl-related ailments.154 GECO management was able to assign operators to 60B who were essentially immune to the effects of tetryl.155

Last, but certainly not least, GECO kept meticulous records of each shift, breaking absenteeism down by category and sub-category. Staff tracked how many operators were absent, not only due to every type of illness imaginable — cold, upper and lower respiratory, gastro, genito-urinary, rheumatic, fainting, nervousness, eye trouble, dental, headaches, and night shift complaints — but also accidents, both explosive and other, and occupational illnesses like tetryl poisoning.156

Through these initiatives GECO management was able to greatly reduce, if not eliminate altogether, the threat of toxicity among their female operators.157 The Toronto East Medical Association’s Official Bulletin in February 1944 acknowledged GECO’s attempt to minimize the hazard of tetryl exposure: “The only girls exposed to the bleaching effect of powder are those filling fuses, and they work directly under suckers (exhaust hoods). This is a very small percentage and the great remainder do a multitude of duties such as assembling, inspection, etc.”158 GECO did not record one death associated with toxic jaundice, and there is no record of any women needing treatment after the war ended.159

If women were leery about working with tetryl, they needed only look to their history, and the Great War for motivation. “Stained hands and coppery hair — what are these?” asked a Great War worker. “Do we fear temporary disfigurement when men, for the same cause, are facing death and the horrible and permanent disfigurement of maimed limbs or blinded eyes? Munition life is the greatest chance that has ever come to us women.”161

Conclusion

Early in GECO’s history, in July 1942, Ross Davis, editor of the plant’s newspaper, made the following observation: “Where in some industries the emphasis is placed almost entirely on maximum production and the worker left to look after his own safety, here the stress was placed — and remains there — on safety. It has been good insurance in the past as “Scarboro’s” record proves — it is good insurance now — and will continue good insurance in the future. All that is needed to keep our record clean is continued good teamwork on the ‘clean side.’”162

Major Flexman, in the last issue of the newspaper, summed up GECO’s exemplary safety record: “Suffice to say that in all the period from 1941 to the present not one serious accident occurred in the production shops of the Plant. This is a unique record and speaks volumes for the efficiency of our Safety Department and for the loyal co-operation of all engaged in the filling shops in carrying out the rules which they all realized were made for their own protection and for the uninterrupted operation of the Plant.”163 Major Flexman’s opinion reflected a huge shift from Bob Hamilton’s early days when he had stated that Scarboro had been “conceived, constructed, organized and operated for but one purpose — production,” where even the safety of their employees did not take precedence.164

When designing the plant at Scarboro, production was foremost on everyone’s minds, however, safety was on the tip of everyone’s tongue. GECO’s safety record was exceptional and unrivalled in wartime munitions plant operations. Despite the odds and the history that preceded them, thousands of women worked with high explosives over four years at GECO and filled over a quarter of a billion units of munitions without one fatal occupational accident.165 From plant design to site security, from burying “igloos” to “super structures,” from windowless workshops to heavy fire doors, from enforcing strict workshop rules to calling out “All Clear!” GECO made every decision with safety in mind.166