11

Rolling Up Their Sleeves: Departments Contributing to Munitions Production

The construction, design, and operation of a wartime munitions plant took the efforts of thousands of men and women over dozens of departments dedicated, directly or indirectly, to the production of GECO’s lethal product line. Management established departments to oversee every aspect of production, ensuring the safety of personnel and property, researching and developing new and improved ways to fill munitions, and supporting the myriad needs of women, who represented the vast majority of their employees.

Production Department: The Buck Stops Here

The Production Department — the heart of GECO’s operation — was responsible for training every clean-side operator, supervisor, and assistant foreman.1 Proper training was critical not only to GECO’s success, but could mean the difference between life and death. Staff managed employee work record cards that contained worker histories, including information pertaining to raises, transfers, and warnings, as well as evaluation statistics for desirable occupational traits such as efficiency, proper deportment, and attendance.2 Meticulous production reporting was crucial to anticipate future munitions-filling schedules.3 The department also addressed any technical production issues that arose.4

Planning and Records: A Juggling Act

Expecting everything to run smoothly in an industry without a precedent in Canada was unrealistic. A new enterprise such as GECO was dependent on supplies from numerous other factories that also were charting unmapped wartime waters. One of the assembly and filling plant’s greatest hurdles to overcome lay in the dependable supply of components. Often production for filling one fuse would ramp up, only to have work suddenly stop and operators switched to other natures.5 This occurred in large part because supplies had not arrived in time.6 These stoppages, while disruptive to the operators in the fuse-filling workshops, and detrimental to the efficiency of production, were all part of the bigger problem of supply. To overcome unreliable component supplies, GECO filled on its own schedule, not based on what production was authorized to fill.7 For example, GECO was authorized to fill four million Primer 15 Mark IIs, but filled over eight million.8 There were no idle hands at GECO. If the parts needed to fill one type of fuse had not arrived, they filled and stockpiled other munitions.

Planning and Records (P&R) provided weekly inventory and requirement sheets to management and supervisors to help anticipate daily, weekly, and monthly component requirements.9 They also managed the Inspection General — a dedicated independent group of people who worked for the Canadian government and were responsible for inspecting fuses, ensuring Canada’s armed forces used top-notch ammunition in theatres of war.10

Just Where Do You Test Explosives?

The only real way to test a fuse’s capability and reliability was to use it in as close to actual battlefield conditions as possible — in Scarboro’s case, at a proofing range. Of course, proofing ranges had to be located where there was no danger to life or property.11 When war broke out, Valcartier, Quebec was home to the only proof range in Canada.12 Valcartier’s proof range strained under the increased demands for testing as D.I.L. in Pickering and GECO in Scarboro ramped up production.13 A second proof range was set up near Hamilton, Ontario, to ease the backlog.14 The Hamilton site, under the direction of retired British artillery officer Colonel Douglas Clapham, was regarded as “one of the most efficient in the British Empire … and the largest establishment of its kind in Canada.”15 D.I.L. at Pickering eventually set up a range, too, which GECO used extensively.16

In addition to testing munitions in a war-like environment, ammo was also tested on a smaller scale at GECO in its proof yard. There were two proof yards within GECO’s confines. Current arsenal practice required keeping separate, unbiased proof yards for both inspectors with the Inspection Board (I.B.) and contractors like GECO.17 In an initiative to calm ruffled feathers between the I.B. and GECO workers, the Canadian government allowed GECO to merge its two yards, jointly operated between the two parties.18 The Proof Yard’s mandate was to test, or “proof,” small samples of filled fuses randomly selected from each lot to determine how well they performed under controlled conditions and then “sentence” — accept or reject — the lot.19 Proof Yard staff were also responsible for testing samples by gunfire or “gun proof;” they tested empties to ensure their safety and capacity to be filled satisfactorily; they experimented with new methods and components; and they tested safety devices for use in filling workshops.20

Speed of proofing was essential — if units failed, shops had to find not only the cause of the rejection, but a quick, safe solution.21 In GECO’s unique “proofing” situation all proofing was done to the satisfaction of the I.B., who reserved the right to carry out their own proofing at any time.22 At GECO’s peak of production, proof yard personnel proofed forty-two thousand units in one month, equating to about 1,750 explosions daily.23

Workers in the Destroying Ground, situated at the southernmost end of the plant, ensured that munitions waste and/or rejected explosives, such as gunpowder, gun-cotton, TNT, tetryl, tracer compounds, caps, detonators, and filled stores were destroyed safely.24

An Explosive Conflict

The conflict between independent inspection personnel and the production team, including workshop supervisors and operators, was, at times, volatile. This was not a problem unique to Scarboro, but one suffered by other wartime manufacturing plants.25 With wartime industry burgeoning in Canada, up to one thousand Inspection Board (I.B.) examiners with little training, and that training based on British requirements, had absolute authority to sentence the quality of work by skilled munitions operators working in Canada.26 GECO employees, for their own safety, were well-versed in working with high explosives and recognized the vital need to get filled munitions quickly to the Allied troops — fuses’ ultimate end users. Within filling shops, work approved by government inspector (G.I.) staff was inconsistent and unreliable. Filled fuses accepted by G.I.s on one shift were rejected on the next, or the quality of work previously rejected suddenly passed inspection.27 Distrust grew between the operators and G.I.s.28 There were glaringly obvious inconsistencies in standards and undependable product quality assurance. This was no small problem given they were dealing with high explosives. GECO offered training classes to Inspection Board personnel, but they declined, perhaps as a matter of principle to maintain an arms-length relationship.29 This exasperated GECO’s employees. In addition, the Inspection Board would not approve changes to filling conditions that had absolutely no impact on the quality of the filled fuse.30 Worse, when they did refuse the changes, they were unable to provide any adequate technical solution to the original problem that triggered the request for a deviation.31 And the final straw? Any changes that GECO convinced the I.B. to accept had to go through official channels in Ottawa, then, in turn, back to England for final approval.32 This was “red tape” at its finest, causing delays neither GECO nor the Allied forces could afford.

With no relief in sight, a New Year on the horizon, and a long war before them, the Hamilton brothers, in December 1941, engineered a unique proposal to mend the ongoing and sometimes hostile relationship between G.I.s and GECO employees. Put simply, Bob and Phil Hamilton obtained approval from the Inspection Board of the United Kingdom and Canada to take over responsibility for all fuse proofing and sentencing.33

On February 15, 1942, GECO established a Factory Inspection (F.I.) Department to act as liaison between Government Inspection and GECO Production.34 The F.I. Department set up checkpoints directly on filling lines to catch potential problems as they happened, to examine empties in order to reduce their rejection, and to negotiate standards agreeable to all parties.35 The department would also oversee inspections in which the Inspection Board delegated responsibility to GECO personnel, or where GECO desired an inspection that was not required by the Inspection Board, to assure quality of product and economy of scale.36 The new department was staffed with a handful of GECO personnel, but more importantly, a considerable proportion of government inspectors moved into the department.37 Enmity and mistrust between G.I.s and GECO workers did not disappear instantaneously. Absolute diplomacy of F.I. staff was needed when interacting with the I.B. Although G.I.s were not paid by GECO, everyone, from that point forward, viewed G.I.s as GECO employees and welcomed them into the GECO family.

Establishing Factory Inspection represented a turning point at GECO, validating management’s drive to produce top quality production while working amicably with all external parties. Inspectors, by working alongside GECO operators, gained confidence in their abilities and personal integrity.38 This helped GECO gain a high degree of co-operation from inspectors of the Inspection Board.

A year later, by February 1943, Factory Inspection had evolved to such a point that the department submitted a plan to management to place newly designated F.I. Examiner-Operators at carefully selected points in the assembly lines. Workers wanted to involve inspectors not only through having them visually examine the fuses, but also during the actual filling — getting their hands dirty, as it were — to ensure the inspections were as accurate as possible.39 GECO staff estimated that 136 fewer operators and I.B. inspectors would be required, while at the same time the efficiency of inspection, and, perhaps more importantly, the authority and prestige of the Inspection Board would remain sound.40 Several highly skilled GECO operators transferred from Production to Factory Inspection later that spring; they received their new titles of F.I. Operator-Examiner and took over inspection points relinquished by the I.B.41

Government inspectors examine filled Primer 15 in Shop 35A. Government inspectors, while paid by the Canadian government, were considered an integral part of the GECO family. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

The amalgamation between separate proof yards ultimately saved GECO 40 percent in operating costs and capital savings, as only one “proof” was needed from each lot with acceptance or rejection agreed to by both the I.B. and GECO.42 In March 1943, seventy GECO workers proofed 46,377 natures at a cost of $13,959.61 in salaries; six months later, thirty-nine proofers tested 46,756 natures at a cost of $6,220.17 in salaries.43 The merged proof yard also greatly increased the degree of co-operation between the I.B. and GECO employees, and saved time and equipment.44

New inspection points resulted in savings in labour and materials.45 By moving G.I.s directly into filling lines to inspect fuses immediately, GECO ensured quality control as it happened, not as an afterthought.46 “Bench leaders” and assistant foremen observed operators’ work, making changes in procedure quickly and easily.47 GECO was able to reduce their operator headcount by eighty-five through this initiative.48

Quality Control: Impressing the Enemy

Ironically, GECO did not formally establish its Quality Control Department until the end of August 1943, a full two years after production commenced.49 Even then, the department was set up only to address new fuse-filling requirements for the Flame Tracer Bullet .303 G II, which called for a much higher degree of mechanization than had been possible on any component filled to date, and for which current inspection protocol did not apply and could not be adapted.50

A lack of a formal Quality Control Department was of little consequence to Scarboro’s quality standards. The plant already had set robust quality assurance standards which were the product of myriad rules and regulations, and the inspection expectations of both Canadian and British governments.

Every fuse that left Scarboro was etched with “Sc/C.”51 Over the course of the war, battlefronts around the world came to recognize Scarboro’s stamp of quality.52 Armed forces knew ammunition marked with “Sc/C” would do the job for which it was designed, filled, and assembled: blow up the enemy. In an ironic twist, German soldiers came to appreciate Scarboro’s symbol and the quality it signified, too. During fierce battles in Italy, when land and equipment switched sides frequently between Allied and German forces, word got back to GECO that German forces were impressed with the quality of ammunition that came from the plant.53

Scarboro was fiercely proud of meeting the highest quality standards set by Government Inspectors, proudly claiming that a rejection rate of just over 1 percent by inspection personnel “was proof of a job well done.”54

“When one considers the magnitude of the task that Canada undertook to do,” wrote Major Flexman in retrospect, “it is surprising that we came through so well.”55

Scarboro’s emblem “Sc/C,” which was etched into every fuse, became a symbol of quality for friend and foe on battlefields around the world. Courtesy of Scarborough Historical Society.

Shipping: We Got Ourselves a Convoy

GECO established its Shipping Department in August 1941.56 The department oversaw all aspects relating to the shipping of filled munitions. The Canadian government prohibited the shipment of explosives via rail, so A.W.S.C. established a “proof truck” service; a convoy of heavy-duty munitions trucks shuttling between munitions plants and proof ranges twenty-four hours a day.57

Research and Development: Safer, Faster, Deadlier

The Research and Development (R&D) team consisted of representatives from several production departments, including Chemical Investigations, Engineering, Factory Inspection, and Experimental Work.58 Finding solutions without the aid of previous experience led indirectly to the adapting of available equipment or the creating of new equipment, which, fortuitously, in many cases, was cheaper than the unavailable equipment.59 Scarboro saw a potential savings in many of their tooling solutions and seized every opportunity to design and manufacture tools that not only saved money but time and labour, and extended longevity as well.

Achievements attributed to GECO’s R&D Department included the invention of an electrical hygrometer.60 The new hygrometer helped GECO personnel control humidity in the air to a strict 55 percent, which previously had been very difficult to measure and helped fine-tune humidity standards in Canada.61

R&D also helped create “stemming” hoods to minimize hazards associated with tetryl dust.62 With the installation of these hoods in workshop 60B — a shop segregated for stemming purposes — operators could work from outside the apparatus, which had built-in ventilators that suctioned air and dust away, greatly reducing deadly airborne tetryl dust.63 Over the course of its operations, GECO saw a continued improvement in stemming tools and equipment. Early on, operators had to hand-pack high explosives into detonators, which exposed everyone to potentially disastrous consequences should a worker pack too much of the deadly powder.64 Through new technical endeavours in Canada and Britain, in 1943 GECO acquired their first automatic stemming machine.65 The new equipment performed three times as fast as hand stemming, and for safety’s sake, more accurately.66 By 1944, GECO had discontinued stemming by hand.67

In August 1942, management established a separate Experimental/Development Department as a sub-group under R&D, located in Building No. 14.68 Employees involved in experimental work easily had the most secretive and deadly job at the plant. Not only did these highly trained engineering and chemical experts handle high explosives every day, they searched for better, more deadly ways to blow things up. This was not child’s play — harkening back to high-school days in a science lab armed with a Bunsen burner and some odourless, powdered concoction a teacher had whipped up. These specimens, if even slightly compromised in handling, had the potential to cause catastrophic destruction to life and property.

“Stemming” referred to the act of pressing a specified quantity of high-explosive powders into certain areas within a fuse without causing an explosion. The plant introduced a dedicated stemming shop — Building No. 60 — which allowed dangerous tetryl dust to be confined to one building and greatly reduced the incidence of rash and tetryl-related ailments. A further refinement to the process involved the introduction of ventilation hoods, which removed the tetryl dust to the outside of the building. Six to eight women could work outside these hoods, keeping air-borne tetryl dust to a minimum. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario

During its first year, R&D handled more than 650 problems, big and small, of which approximately four hundred involved work carried out by the Experimental/Development Committee.69 By mid-1943, GECO had registered twenty-two new or improved pieces of machinery for use by the United Nations.70

Purchasing: Axes, Apples, and Ammo

In late January 1941, GECO filled out its first purchase order for the future munitions plant: one small and two medium axes to drive survey stakes into frozen ground at the newly chosen site in Scarboro.71 Bob and Phil Hamilton established their Purchasing Department at GECO four days after construction workers broke ground.72

The need for abundant amounts of construction materials to build more than 170 buildings began in earnest in early 1941, and included estimates for 14 billion board feet of lumber, wallboard, rock wool for insulation, material for electrical, plumbing, and heating installations, roofing, flooring, and hardware.73 Once construction was well underway, by May 1941, the emphasis for the Purchasing Department shifted to buying supplies to equip plant services, such as two fire halls, a hospital, the cafeteria, and the laundry.74 Emphasis shifted again, in July and August 1941, when purchasing for initial production commenced.75 While the Planning and Records Department made purchases for components and materials directly related to actual production, the Purchasing Department was responsible for appropriating the extensive variety of materials, equipment, and supplies needed to manage a sprawling military complex.76

Materials and equipment were regularly in short supply, often causing delays in delivery.77 Slowing things down further was the fact that purchase orders could not be made by telephone, just in case the enemy had infiltrated the phone lines78 This requirement precluded the possibility of speedy delivery of any purchase to Scarboro, whether it was gunpowder or apples. As a result, the Purchasing Department had to anticipate requirements well in advance, so as not to hold up production.

In the end, staff placed 36,344 purchase orders with nearly 1,300 firms for about ten thousand different items.79

Engineering General Office: Ground Zero

The massive Engineering General Office handled all plant construction, maintenance, transportation, (including trucking and roads), fire fighting needs, and mechanical services.80 Crucial co-operation and a congenial relationship between the General Office and all other departments at the plant was fundamental to GECO’s success, with their decisions affecting the health, efficiency, safety, and welfare of everyone at the plant. One of the first departments to be established, Engineering was responsible for everything from supplying water and power to changing light bulbs, from controlling air conditioning to servicing toilets, from creating special tools to building office furniture, from providing fire protection to keeping the roads in good repair.

GECO’s munitions production ran around the clock, six days a week, which put a tremendous demand on equipment and tools within fuse-filling workshops. Tools broke and small parts were lost. With strict communication protocols placed on GECO as a wartime government plant, a potential three- to eight-week delay was possible if broken parts had to be shipped out to be fixed or new parts ordered in.81 GECO management anticipated this problem and “fixed” it early by strategically incorporating a tool and machinery shop into its original plant design.82 In fact, Building No. 7 was the first building to be completed and equipped within weeks of breaking ground.83 Filled with lathes, drill presses, shapers, steel hardening and tempering equipment, and other machines, GECO’s Tool and Machinery shop was one of the best in the country at the time.84 Highly skilled mechanics replicated or repaired parts within a precision of 1/10,000th of an inch.85 With the repair shop right on the premises, employees often enjoyed same-day service in GECO’s “tool hospital.”86 The shop handled more than two thousand repair jobs per week.87

Maintenance workers at GECO looked after the site’s buildings as well as the plant’s extensive grounds and transportation needs.88 Grounds Maintenance was responsible for GECO’s tunnel system.89 The Transportation Department managed all plant vehicles, which included taxis, explosives trucks, station wagons, general-purpose trucks, and snowplows.90

The Sawdust Brigade

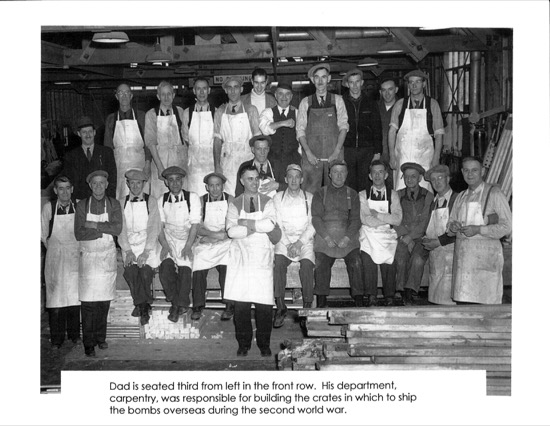

The carpentry shops at GECO, housed in Buildings 8 and 142, were a woodworker’s dream.91 About seventy-five older men, affectionately called the “sawdust brigade” and mostly First World War vets from the “Old Country,” worked tirelessly, producing everything from boxes for shipping filled munitions to fine desk furniture, from station wagons to hat racks.92

Once construction of GECO was completed, seventy-five older men, with 2,300 years combined construction experience, stayed on in GECO’s carpentry shops working tirelessly producing a wide variety of wooden treasures: boxes to ship filled munitions, fine desk furniture, toys for war-time nurseries, and playground equipment for GECO’s employee field days. Carpenter Alexander Licorice Waddell is seated in the front row, third from the left. Courtesy of Barbara Dickson, from Scarborough Historical Society.

One of the department’s proudest accomplishments was the design and manufacture of a fully functional station wagon from scratch, using no blueprints.93 This wagon, “resplendent in its varnish and new paint,”94 eased the burden of proof yard personnel having to walk almost half a mile each way in all kinds of weather to and from the southern end of the plant for their shift. It also offered quick relief to fence guards.95 A second station wagon emerged from the shop later, bigger and sleeker, with all the bugs worked out.96 By war’s end, GECO had amassed a fleet of more than thirty vehicles, including two blue firetrucks — one without a speedometer — an ambulance, munitions trucks, tractors, a jeep, and the big blue twelve-passenger station wagon fondly dubbed the “Blue Goose,” which operated as a shuttle between Scarboro and Pickering’s proof range.97

While the “boys” in Shop 8 built toys to donate to wartime nurseries, and built playground equipment for GECO’s Field Days, their most important contribution to the war effort was shipping boxes.98 After empties had been unpacked, the boxes were revamped to house filled munitions, fondly referred to as “Hitler’s headaches.”99 “Booster” boxes built at GECO numbered in the thousands, but due to the secretive nature of GECO’s work, total boxes built was just one of countless statistics that were not divulged.

Every man on the sawdust brigade felt he did “his bit towards bringing the war to a successful conclusion.”100

Other Departments: Smaller but Just as Deadly

Several other departments supported production at GECO. The Chemical Investigations Department (C.I.D) started with just one man, Mr. E. Littlejohn, but over the course of Scarboro’s operation, C.I.D. would grow to a staff of thirteen working in a well-equipped modern laboratory.101 Staff in the Time and Motion Department worked to increase efficiency and speed in fuse-filling operations.102 Through extensive evaluation and study of fuse-filling methodologies, personnel introduced processes that saved $15,942 per month, the equivalent of constructing a new 5,700- square-foot GECO building every month, with money to spare.103

The Textiles Department’s mandate at GECO was to produce paper and cloth components, which to the casual observer may have seemed like dull work. Textiles manufactured at GECO were anything but dull. These creations encompassed washers, discs, tabs, patches, strips, and paper capsules needed in the filling of deadly ammunition such as fuses, tubes, primers, and gaines.104 These small yet potent “textile” components were essential in maximizing the potency of GECO’s product line.

The Pellet and Magazine Group took care of GECO’s most deadly inventory: explosives, initiators such as caps and detonators, and pellets.105 Workers received, stored, prepared, and released all explosives and components to workshops as needed. They also were responsible for producing pellets needed for most percussion and time fuses.106 Small pellets, filled with tetryl, were positioned within the fuse, which, once detonated, set off the substantial bulk of explosives housed within a shell or other large armament. Pellets filled with gun powder were also used in some munitions filled at the plant. Their safety record was exemplary, despite their dangerous stock: “The great mounded magazines,” management recorded proudly, “in which hundreds of tons of high explosives, gunpowder, and fuse powders would be stored, were processed without accident during Scarboro’s history …”107