12

Nothing Less Will Do — Employee Morale

The Situation Room

By the time GECO launched its massive hiring campaign during the fall of 1941, the war in Europe was well into its third year. Hitler had seized Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, and was doggedly determined to annex Britain and Russia. The need for munitions was acute. It would be only three months before Japan launched its assault on the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor.

The free world was at war and no life in Canada, or overseas, was exempt from its troubling effects. GECOnians lived, worked, and prayed on the home front. They read the evening newspaper filled with grim war news. They gave up sugar in their tea, and precious dollars for war bonds. They watched as sombre staff delivered telegrams to fellow GECOnians in their workshops, announcing the saddest news of all — that a loved one was missing in action, had been taken prisoner, or had been killed while fighting the enemy.

The women of GECO gave every fuse their full and undivided attention, not only because they were handling high explosives, but also because they wanted their men home. Great Britain, homeland to many women at GECO, was taking a pounding Luftwaffe-style. Besides, what was the alternative? Ominous words appeared in GECO’s employee newspaper less than a year after plant productions got underway:

It’s hard to stick at a job we may not like, to work under people we may not like, and harder still to contemplate handing over to the government the major portion on one’s surplus earnings.

The fact is that the whole grim business is hard — but it will be harder still if we do less than everything we know how — and lose the war.

If anyone thinks otherwise, let him read and digest what is happening in Poland, Holland, Czecho-Slovakia, Jugo-Slavia, and Greece. The folks in these countries would give their souls to be in our shoes today.”1

The GECO Diamond Is Their Badge

There were no shift quotas at GECO.2 They weren’t needed. The deaths of Canadian soldiers steeled the women’s resolve to fill as many fuses as fast as their deft fingers could manage. Instead, Bob and Phil offered service badges, rewarded for completing years of faithful service.3 Operators strived to achieve this simple yet solemn mark of distinction, which they wore on their left sleeve.4 Workers earned a red diamond-shaped badge after one year, green after two, blue after three, and a large gold badge after four years of service, which replaced the former three and had the number “IV” embossed on it.5 Inspector Carol LeCappelain was disappointed that Germany surrendered when it did; she had just weeks until she would have received her gold badge.6 Management issued letters of congratulations for faithful service as well,7 and these became treasured keepsakes for employees and were used as references after the war.8 GECO also offered employees the chance to join their “100 Percent Club” for exemplary attendance.9 GECO employees proudly wore their company’s insignia on their uniforms, and GECO flags flew from the company’s mast and hung in the cafeteria. Other visible symbols of pride for employees included GECO pins worn proudly on civilian clothing.10 With each worker’s individual employee number etched on the back, every pin depicted a maple leaf and beaver symbolizing Canada, the GECO diamond indicating the company’s trademark, and in bold lettering the words, “Munition Worker.”11 “This pin not only identifies the wearer as an employee of the Company,” wrote R.M.P. Hamilton in a review of Industrial Relations mid-1943, “but also symbolizes his (or her) part in the Canadian war effort. It is worn with pride and is most helpful in its influence on ‘esprit de corps.’”12

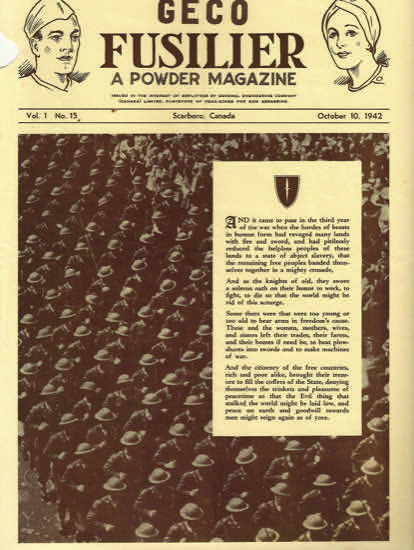

GECO Fusilier: A Powder Magazine

The Hamiltons and the Canadian government appreciated the far-reaching positive ramifications an employee publication could have on its readership. Management gave Mr. Ross Davis the mandate to promote loyalty, morale, and unity amongst its employees through their “powder magazine.”13 Each issue of the GECO Fusilier not only kept the GECO community informed of “all things GECO” but encouraged a dedicated work ethic and an unparalleled safety standard within wartime industry as well. Ross put together an enjoyable read that left women’s heartstrings suitably stirred, chock-full of cartoons, inspiring stories, birth, engagement, and wedding announcements, and friendly inter-department competitions. The plant issued eighty-four editions and it had expanded to eight pages from its original four after its first year of publication.14

GECO workers were reminded by editor Ross Davis that while they couldn’t be “the man behind the gun,” they all could be “the man behind the man behind the gun,” and that “it is up to us to be good and sure that ‘the man behind the gun’ has plenty to put in his weapon when he brings his sights to bear on the hordes of Axis assassins.”15 In fact, in just the second issue of the newspaper, printed in April 1942, Ross wrote, “The storm signals are up. There is no question but that the Axis powers are all set for a ‘knockout’ this year. Millions of men armed to the teeth are on the march. The hurricane is about to hit in all its fury and soon. Let us not delude ourselves — we can lose.”16

Cartoonist Lou Skuce created cartoons during GECO’s early days using humour and wit to foster patriotism and a dedicated work ethic. In this drawing Mr. Skuce likens munitions workers’ war effort to that of servicemen, deserving of a medal. For a GECO worker her medal was her company pin worn proudly on her civilian clothes. Author’s photo.

When it came to patriotism and commitment to the war effort, Davis didn’t mince words. The newspaper pointed out that those who did not have perfect work attendance were “Hitler’s Helpers.”17 Ross posed the question, “… what essential difference is there between a fighting man deserting his post in time of danger — and a worker in a munitions plant?”18 In fact, quite regularly, the newspaper employed guilt tactics to motivate its readers. The following text appeared in the “Editor’s Column” in the paper’s inaugural edition in regards to shortages in supplies: “… these materials have been brought across sub-infested seas and brave men are daily risking and losing their lives to ensure that we get them. What a pity if we should be found guilty of improper or wasteful use of things so costly.”19

GECOites with a penchant for poetry wrote about the men who were dying overseas, of their bravery in the face of death, of their sacrifice, and of the shame the nation should feel should the men die because citizens didn’t do their very best to supply fighting men with the “tools” needed to get the job done. Mr. William “Bill” Taylor wielded an especially sharp pen, and was a regular contributor of poems to the newspaper.

“A Young Canadian Died!”

For want of a shell a gun was still;

For want of that gun on a Flanders hill

A Hun in a foxhole was free to kill—

And a young Canadian died!

For want of a fuze that was yet unfilled

A shell was lost and a gun was stilled;

And a Hun was alive that it should have killed—

And a young Canadian died!

For want of the hands of a worker skilled,

The task of a fuze was unfulfilled;

And a gun was mute, and a Hun was thrilled

As a young Canadian died!— Bill Taylor20

Skuce’s Goose

GECO hired “Canada’s Greatest cartoonist” Lou Skuce to create posters and cartoons for the GECO Fusilier during the first year of the plant’s operation.21 Taddle Creek Magazine’s Conan Tobias called Skuce “… something of an international celebrity throughout the thirties and forties, achieving a level of fame unthinkable for a newspaper illustrator today.”22 Lou Skuce relied heavily on humour to convey serious messages. His iconic goose — the infamous Skuce Goose — showed up in many of his cartoons. The goose became almost as famous as his creator, with his tiny top hat balanced on his head. Mr. Skuce presented his goose in a “Jiminy Cricket” role, reacting to and offering sage counsel to his audience.

Cartoonist Lou Skuce drew unabashed anti-Nazi cartoons to send a crystal clear message to Hitler and his minions. This drawing features an Allied soldier shoving “bitter pills” — ammo produced by GECO — down Hitler’s throat in retaliation for the massacre at Dieppe in 1942. Courtesy of Barbara Dickson, from Archives of Ontario.

A Little R & R

With the payment of dues of $1 per year, GECOites could join the company’s Recreation Club, which sponsored a variety of sports, dances, and entertainment throughout the year.23 Diverse and plentiful social activities catering to men and women, old and young alike, were available, making it a challenge for any GECOnian to partake in every activity. Within GECO’s environs, workers could play volleyball, horseshoes, lawn bowling, croquet, and softball.24 Employees even found space to set up a nine-hole mini golf course between Building Nos. 144 and 23.25 An area set up in the cafeteria provided room for table tennis, badminton, shuffleboard, cribbage, checkers, bridge, euchre, and dramatics.26 Away from the plant, people could enjoy bowling, trap shooting, horseback riding, swimming, and tennis. The men established six hockey teams and the women pleasure-skated on two skating rinks set up each winter at the plant.27 GECO’s Saddle Club included sleighing during the winter months at Three Gaits Stables, also known as Hilltop Boarding and Riding Stables near Wardin and St. Clair Avenues in Scarboro.28 Bingo was so popular that sessions had to be limited to five hundred people.29 Monthly dances had upwards of one thousand in attendance. Various lessons were offered, including dance classes, health and beauty tips, nutrition sessions, and sewing classes. The plant also had a Glee Club.30 Finally, if employees were looking for something more, they could purchase memberships for up to 25 percent off to the YWCA.31

Sing a Song of Softball

GECO installed four baseball diamonds on the northeast corner of Eglinton and Wardin Avenues, with eighteen men’s teams in three leagues and fourteen women’s teams in two leagues launched.32 Fierce competition ruled the day between fellow GECOites. Recognizable team names such as “Stores,” “Pellets ‘A’,” “I.G.,” and “Time Office” easily identified where the players worked, whereas more ingenious names such as “Geco Aces,” “Commandos,” “Tank Busters,” “Woodbutchers,” and “Gecolettes” spoke to an individual team’s pride and imagination.33 GEOC’s most recognizable pair, “Dazzy” Bob Hamilton and his brother, “Drop’em” Phil Hamilton, played on the “Whirlwinds” team.34

GECO installed four baseball diamonds on the northeast corners of Eglinton and Wardin Avenues. Fierce competition ruled the day between fellow GECO teams, as well as against other war-time plants. In this photograph, a couple of softball players are wearing GECO’s colours on their shirts. The plant’s administration building and signature smokestack can be seen in the background. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

Bombs Away, Beautiful!

The Toronto Police Amateur Athletic Association sponsored the Miss War Worker Contest annually; open to women sixteen years of age or older and engaged in war work in the city.35 GECO participated each year, with several dozen entrants vying for the title of “Scarboro Miss War Worker.”36 Six to eight finalists from this competition went on to next round held typically at Acorn or Sunnyside Park.37 While many lovely GECO ladies entered each year, with several of their “Miss Scarboro” finalists placing at the semi-final and city-wide events held at Exhibition Park, the coveted first-place prize remained elusive, although several beauties finished in the contest’s top ten.38 GECOite Kathleen Russell took fourth prize in Toronto in 1942, and Mrs. Alice Newman and Eunice Harrison took second and fourth place in 1943.39 In 1944, GECO’s Lottie Walsh placed third at the city event, and Grace Bollert and Sylvia Jenkins ranked in seventh and tenth place respectively.40

Miss War Worker Finals, July 1942. Every year GECOites competed in Toronto’s Miss War Worker Contest, open to any woman over sixteen years of age engaged in war work. GECO held its own competition each year, sending several lovely “Miss Scarboro” finalists to the semi-final and city-wide events held at Exhibition Park. This photograph offers a rare glimpse into the plant’s massive cafeteria with its freestanding “laminated beam” construction, a GECO engineering innovation. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

In 1943 GECOites Margaret Miller, Grace Bollert, Eunice Harrison, Alma Campbell, Kitty Russell, and Alice Newman represented Scarboro in the Miss War Worker Contest at the Toronto Police Amateur Athletic Association’s Annual Field Day. Five GECO women remained in the final ten chosen at the city-wide event. Alice Newman came in second, winning $150 and a chest of silver. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

Major Flexman, GECO’s operations manager, added a sombre note during the preliminary event in 1944 when he stressed the need for more and more ammunition, and made an urgent appeal for employees to find more recruits.41 In fact, R.M.P. Hamilton allowed GECO to participate in the beauty pageant in 1944 — held within weeks of the Allied Normandy invasion — only if there would be no interference with production.42 “The necessity for this condition,” stated Mr. Hamilton in a formal notice to all employees, “will no doubt be realized in view of the fact that the demands for ammunition at this time are urgent and must take precedence over everything.”43

To celebrate the beauty of GECO’s feminine side, in March 1944 management introduced a new morale booster — pin-up girls.44 Each shop on each shift had the opportunity to select one “pin-up” girl who best represented their shop.45 Selected women appeared in future issues of the employee newspaper.46 Beauty and health classes were also popular at GECO.47 The men, who enjoyed “pin up” girls, did not think so much of beauty lessons, and were known to tease their female counterparts. Their attitude was adjusted via a smart article in the GECO Fusilier. The plant’s men were reminded that there existed a serious problem with distribution of coal in major cities due to a labour shortage.48 The scuttlebutt around the plant hinted that men from munitions plants might be “utilized” to shovel coal.49 The employee newspaper reminded men it would be to everyone’s benefit if the teasers kept their beauty comments to themselves, since “he laughs best whose face is unsullied by coal dust.”50

Victory Gardens

In 1943, on the northeast corner of Wardin and Eglinton Avenues, GECO established a “Victory Garden.”51 Workmen plowed twenty-six acres of farmland, preparing more than six hundred plots, each measuring twenty by sixty feet.52 More than five hundred employees took advantage of the opportunity to try out their green thumbs.53 They undertook their sowing with eyes wide open. Should the winds of war change, the gardens would be taken to accommodate Canada’s war needs.54 Management encouraged workers to plant vegetable gardens, since a food shortage was a constant worry throughout the war. The more food cultivated by citizens, the more foodstuffs could be sent overseas to help feed the troops. In fact, in anticipation of the upcoming gardening season in 1945, the plant newspaper warned, “Food may be in short supply this year. Better arrange to have a garden.”55

More Mistletoe and Less Missile-Talk

During each annual Advent season, employees savoured a full-course turkey dinner with all the trimmings in their spacious cafeteria for “two bits (twenty-five cents).”56 The repast cost GECO fifty cents per employee.57 The meal, meant to serve upwards of five thousand employees, included (approximately, depending on the year) 400 turkeys (from 1.5 to 2 tons in weight), 300 loaves of bread (for stuffing), 80 gallons of gravy, 25 to 30 bags of potatoes, 25 cases of canned peas, 12 gallons of cranberries, 27 gallons of apple jelly, 1,200 pounds of pudding, 300 pounds of brown sugar, and 200 gallons of coffee.58 In 1943, cafeteria staff clocked 846 hours of regular time and 118 overtime hours to plan, procure, prepare, and serve the festive holiday meal.59 GECOite “chef” Karl Markovitch worked twenty-four hours straight preparing turkeys.60

In 1944, due to significant snowfall, the turkeys were three days late arriving at the plant.61 Mrs. Ignatieff, anticipating thousands of sad faces, procured hams — just in case.62 The turkeys arrived in the (St.) Nick of time. They even managed to enjoy cranberries, which had turned up after being lost somewhere between Montreal and Toronto due to heavy snow.63

Each year, GECO held a Christmas party for the children of their employees.64 The official program consisted of a festive hour of entertainment, with a magic show, musical performances, and clowns, and was offered three times over the course of an afternoon. Overcrowding was a concern, so management gently told their employees to bring their children, enjoy the show, and then leave promptly.65 Record snow from the “storm of the century” on December 12, 1944, made the munition plant’s Children’s Christmas Party, held only four days later, even more festive. A record number of guests — more than 2,500 youngsters and their happy parents — partook in the festivities, eager to receive a toy from Santa.66 Local bus lines carried 12,574 excited and happy passengers to and from GECO that afternoon.67

The Kids Are Alright

Daycare was virtually non-existent before the Second World War. With the war’s outbreak, tens of thousands of women took up war jobs, working six days a week, and could no longer care for their pre-school children at home. To ease the burden, the Canadian government introduced a “wartime day nurseries” program developed with the joint sponsorship and financial support of the provincial governments, which commenced in earnest during the fall of 1942, offering childcare to children two years of age and up.68 War factories offered the service to mothers at a nominal daily charge of thirty-five cents for one child, or about the equivalent of the women’s first hour of work at GECO each day, and fifty cents for two.69 This fee did not meet the expense of providing for the children. The balance of the cost was made up by Canada’s federal and provincial governments.70 The intent of the program was “to relieve mothers of smaller children, who are employed in war industries, of the responsibility and the worry of locating someone capable of and willing to look after her progeny while away at work. It should furnish the answer to a major problem of a great many ‘working’ mothers.”71

Before children were admitted to the day program they had to undergo an extensive medical exam, including a throat swab.72 A Public Health nurse visited the facility three times each week and a doctor paid a visit weekly, hoping to ward off the spread of viruses that could overwhelm the nursery, cascading into lost days of work for mothers.73 GECO was affiliated with “Unit No. 7” Day Nursery, which operated out of the basement of Dentonia Park United Church and at 125 Rose Avenue, near Parliament and Bloor Street East.74 Women engaged in war work comprised 75 percent of the parents who used day nurseries during the early 1940s.75 Women saw the nursery as an excellent avenue to expose children to social interaction and to learn how to be kind to others. Women had peace of mind knowing competent nursery staff cared for their children.

Big Business Unions

By December 1941 GECO’s management had employed and trained more than three thousand operators.76 With hundreds more expected to join the ranks over the ensuing months, Bob and Phil Hamilton quickly recognized that they needed some systematic way to acknowledge merit and control wages. Staff introduced a work record card system that contributed to an enduring amicable relationship between the plant’s “labour” and “management.”77

GECOites recognized a need for some sort of intermediary group to take their needs and concerns to management. With Bob and Phil’s encouragement, and at their request, employees organized the GECO Munition Workers’ Association.78

Until Canada’s federal government passed legislation in 1944 to enact labour reform — in particular, provisions for union certification and collective bargaining in good faith — the Munition Workers’ Association (M.W.A.) was not a union.79 Even after the association was made more formal and referred to as Local No. 1, there was no other.80 Unions tried to organize GECO’s operators in filling shops during the course of the plant’s operation, but, for the most part, workers were happy with their M.W.A., with management’s commitment to keep the lines of communication open and to maintain a high standard of working conditions and boost morale.81 This dampened any desire to form a union. Unions formed at other war plants, especially when the labour situation grew graver after more and more men shipped out, allowing workers to demand higher wages.82 Unionized shops received a 10 to 20 percent pay increase; non-unionized plants like GECO had to strive diligently to keep their employees happy to remain competitive.83

The M.W.A. worked with management. They found ways to conserve materials.84 They helped eliminate sources of operator “irritation” to reduce absenteeism, and they introduced changes that would have a positive effect on working conditions and relationships.85 The association issued an off-white booklet entitled What the M.W.A. Can Do, describing the role and responsibilities of the association.86 The M.W.A. guaranteed a “no strike” policy to give workers peace of mind.87 It guaranteed that it would not get involved in “big business unions.”88 The association would bargain collectively for fair wages and working conditions, ensure seniority and overtime rights, negotiate for legal holidays with pay and double pay, and obtain extra pay for afternoon and night shifts.89

Elections occurred annually.90 The M.W.A. represented all workers below the rank of assistant foreman on the clean side and foreman on the dirty side.91 Employees nominated candidates from within their shop or department.92 Each department elected a representative — approximately one for every fifty employees.93 Those representatives appointed an Executive Plant Council — one for every two hundred employees — who met with management knowing they took any grievance from the M.W.A. seriously.94

The only labour strife Bob and Phil Hamilton encountered at GECO occurred over the course of one shift on September 11, 1942.95 The operators in Building No. 63 refused to work due to “working the worst shift without relief.”96 The operators had worked many days without a day off due to demanding production schedules attributed to fierce fighting overseas. The women were exhausted and feared they would make a fatal mistake borne of crushing fatigue. The M.W.A. got involved immediately, the employees returned to work, and shortly thereafter operators in three other buildings, in solidarity with their fellow fuse-fillers, agreed to go on rotating shifts.97 Within weeks all workers on the clean side of the plant adapted to shift rotation.98 GECOnian Sylvia Nordstrand said the only aspect she did not like about working at GECO was doing shiftwork. It “played havoc with your sleep. You no sooner got used to sleeping on one shift when you had to change to another. The night shift was the worst. You couldn’t sleep when you got home in the morning. Then while working at 2:00 a.m., you would give anything for sleep.”99

In another less serious incident, workers in the Pellet and Magazine Section threatened to strike because they felt they deserved higher wages given the extraordinary dangers of their work.100 The M.W.A. took their grievance to management, who moved quickly to adjust their wages accordingly.101

Winning the war was, for the vast majority of employees, the motivation behind every fuse filled at GECO. Regardless of striving for optimal working conditions, or crabbing about petty inconveniences, women showed up for work every shift in a dedicated bid to bring their loved ones home quickly. “The war must be won,” it said in M.W.A,’s booklet. “A better, more democratic and free M.W.A. in G.E.CO. will help YOU and your kinfolk overseas to win the war.”102

Blood Is Thicker Than Water

GECO held its first blood donor clinic on December 2, 1942, as part of the Canadian Red Cross Society’s new initiative to go to donors instead of donors coming to them.103 This first blood drive collected sixty-one donations.104 Word spread rapidly and at the next clinic workers made 111 donations, almost double that of the first.105 GECO held weekly blood donor drives over the course of the war.106 By the time Scarboro closed its doors, GECOnians had donated 8,453 units of blood.107 Additional “on call” blood donors were available at GECO should an emergency arise, such as an explosion.108

“We are constantly receiving reports of the value of dried human serum,” wrote Mr. G.R. Sproat, Director of Blood Donor Services, in a thank-you letter to GECO workers.109 “It is being used in the front lines with great results. It must be a source of great pride to the donors to know that their blood is helping save lives of their brothers and human kind throughout the Allied fighting fronts.”110

I’m Making Bombs and Buying Bonds

Wars cost money. Canada needed $12 million a day to fulfil its military obligations and help Allied prisoners of war.111 With a promise to give their money back with interest at predetermined rates and redemption dates, the Canadian government, aiming to raise a staggering $750 million through just one victory war bond drive, asked its citizens to buy bonds and War Savings Certificates.112 By Canada’s fifth drive, that individual bond objective had grown to $1.2 billion.113

GECO employees purchased almost $4 million in bonds over the course of the global conflict.114 By the time the first edition of the GECO Fusilier went to print, the second Canada Victory Loan campaign — the first for Scarboro — was finished.115 Management had asked GECOites to meet a $150,000 quota in two weeks.116 Employees more than doubled that amount with total subscriptions of $327,939 with practically 100 percent participation.117 Bob and Phil Hamilton wrote, “Although we have learned to expect thoroughness in everything undertaken by the employees of this plant, your effort in this campaign surpassed our highest hopes. We thank you sincerely.”118

GECO set their next Victory Loan goal at $350,000 but with still a week to go, the plant already had raised $322,500, so GECO raised their quota.119 “Our real objective is not $350,000 or $400,000 or any other arbitrary figure —” wrote Ross Davis in the employee newspaper, “— it is to do our utmost, whatever that may be, to blast from the earth these beasts who cast little children adrift in open boats in the mid-Atlantic to perish, who glory in the murder of defenceless people. That’s our real objective.”120 Employee purchases totalled $384,844.121

By the end of Canada’s fourth Victory Loan campaign, GECO employees purchased $545,000 in bonds, easily surpassing an already aggressive goal of $504,800, which had been increased from an initial target of $385,000.122 To maintain employees’ enthusiastic drive to give, F.G. Pope, Chairman of GECO’s Victory Loan Committee, asked workers to “… show the Madman of Berchtesgaden that we’re 100 percent behind the War effort. Why wait another six months till we tell him again? Let’s tell him again and again, every single day, by the way we conduct ourselves by sticking to our respective jobs, by the way we produce things to hit him with — that we’re in this struggle with all we have, and for all we can produce till Victory is won and Freedom assured.”123

GECO employees purchased almost $4 million in bonds during Canada’s Victory Loans campaigns. Stirring poems and articles appeared in the employee newspaper during the bi-yearly bond appeals. Workers were encouraged to bring “their treasure to fill the coffers of the State, denying themselves the trinkets and pleasures of peacetime.” Courtesy of Barbara Dickson, from Archives of Ontario.

During the next bond drive, held in the fall of 1943, the employee newspaper dedicated an issue to encourage subscriptions through heart-stirring articles. Bill Taylor, Engineering, wrote:

These boys — sailors, soldiers, airmen — they are offering everything they have, even to life itself, as their contribution to the speeding of the victory. Seems ridiculous that we should be asked to contribute — what we have to spare! Crazy, isn’t it? Home; wife; family; food; comfort; security; and what’s left after these have been assured we are asked to loan as our contribution to victory. Not to give; just to loan! Over there, they are willing to give everything! Over here, are we willing to loan all we have to spare — and that extra that means victory?

There isn’t any option — for a Canadian. It has to be every cent that can be spared — every cent that can be squeezed from the savings of the past, the earnings of the present, and the wages of the future. Without these cents and dollars there won’t be any future that’s worth while; for Canadians. The job of the moment is to Speed the Victory! Our part is to provide the dollars for the material that means Victory.124

Neither time nor the hint of the war ending had much effect on the drive to buy bonds. During Canada’s seventh bond drive, GECO raised $788,950, 42 percent over their target of $555,000, with a subscription rate of $139.59 per employee.125 By the eighth Canadian Victory Loan campaign — the seventh for GECO — employees were still eager to help the war effort financially. Victory in Europe was palpable and fund raising now focused on returning, reuniting, and rehabilitating loved ones.126 GECO’s target set at $560,000 was met the first day.127 They would go on to achieve $682,500 in purchases with an average of more than $150 subscribed per employee.128 Subscriptions for seven campaigns held at GECO totalled a stunning $3,873,643, or the equivalent of more than $51 million dollars today, assuming 3 percent interest.129

The Good Ol’ Sally Ann

In yet another initiative, GECO employees raised $2,500 toward the purchase of a Salvation Army Mobile Canteen, above and beyond their support in Victory Loan drives.130 “Whether it is army manoeuvres in England,” Ross Davis wrote in GECO Fusilier’s Vol. 2 No. 2 edition, “—commandos returning from a raid on the continent — the navy back in a home port after the perils of the sea — on the landing fields after a bombing raid over Germany — or “blitzed” areas in Britain — everywhere that men and women doing their bit in this war need the lift of a cup of tea, biscuits, hot chocolate, or cigarettes to relieve the strain of war, there you will find mobile canteens.”131

GECOite Peggy MacKay, on behalf of GECO’s employees, presented a cheque to cover the purchase of the canteen to Colonel W.J. Bray, Canadian Secretary of War Services of the Salvation Army.132 “The story of the mobile canteen is one that comes close to the hearts of all people of humanitarian instincts,” Ross Davis wrote, “for it is a saga of help in a most practical form to those who are fighting our battles for us.”133

The Salvation Army is not a military organization, but rather an evangelical Christian church founded in 1865 in London, England’s East End, where poverty, disease, alcoholism, and homelessness ran rampant.134 Its founder, William Booth, a Methodist minister, felt that a human being’s soul couldn’t be fed until their stomach was full.135 The Army’s motto is “Heart to God — Hand to Man,” and today, according to the organization, it is the largest non-governmental social services provider in Canada.136

Pennies from Heaven

Friendly rivalry and competition throughout the plant not only helped build morale, but also helped raise money for various war-related causes. One of the earliest philanthropic undertakings originated with GECOite Ruth Richards, who worked in Change House #17.137 Britain was in the throes of the Blitz at the time. The plight of its people touched her heart. Why not collect pennies to support the British War Victims’ Fund? Each payday, small red boxes marked “B.W.V.F.” were set out in the change houses into which operators dropped their pennies, nickels, and dimes.138 While there wasn’t any “prize” for the shift house that raised the most money, fierce competition amongst the women propelled the original and seemingly aggressive target at the outset of one thousand dollars to a considerable chunk of copper.139 By June 1945 GECOites had raised more than $11,000.140

Special Guests

During its four-year lifespan, GECO had many distinguished visitors, especially during Victory Loan campaigns. Special guests of note included His Excellency the Earl of Athlone, the sixteenth; governor general of Canada and his wife, H.R.H. Princess Alice; Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton; the minister of national defence; Toronto mayor Fred Conboy and his wife; and Ms. Mary Pickford, the Canadian actress ardently dubbed “America’s Sweetheart.”141

GECO played host during the war to many military dignitaries and well-known entertainers. Canadian actress Mary Pickford visited the plant during a Victory Loan campaign. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

Just before Christmas 1942, GECO workers found brightly coloured handkerchiefs tucked next to their paycheques.142 Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Bernheim of New York City, who had visited the plant earlier that fall, wanted to present a small gift to the women in recognition of their devotion to duty.143 Three hundred and fifty dozen handkerchiefs were manufactured in the plant with which Mr. Bernheim was connected,144 and GECOites showed off their gifts with pride. Photographs taken over the course of the war attested to their popularity.145

The Songs They Sing Are Preludes to the Voices of the Gun

Unlike other war plants where employees manufactured heavy machinery, women who worked at GECO enjoyed clean, quiet working conditions. As an extension to their pleasant surroundings, and perhaps as an informal indication of plant morale, operators on the clean side regularly sang as they walked through the gallery system or while they filled munitions.146 Canada’s governor general, His Excellency, the Earl of Athlone, witnessed this cheery phenomenon first-hand and remarked that in the “corridors and on the assembly lines, [the women] broke into spontaneous song.”147 Sylvia Nordstrand, a GECO fuse-filler, said they sang to fight sleep and break up the monotony. “Someone would, say, sing ‘Deep in the Heart of Texas,’ ‘There’s a Long, Long Trail A-Winding,’ or ‘I’ll Never Smile Again.’ Each of us would request a song and all would join in singing. It certainly passed the time beautifully. We never got tired of singing, including our supervisors who joined in.”148

In a letter to R.M.P. Hamilton on May 5, 1943, L.H. Campbell Jr., Major General, Chief of Ordnance, War Department, wrote: “… it was most unique and enjoyable to hear the girls sing during their work. It certainly was apparent that the morale was exceedingly high!”149

Canada’s governor general, His Excellency the Earl of Athlone, and his wife, Her Royal Highness Princess Alice, visited GECO in March 1944. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario.

Every Fuse You Fill May Save a Life

Women of GECO were reminded regularly that “plenty of ammo” meant a “savings of precious lives” — a dichotomy to be sure and one against which civilized society grappled.150 Men on the battlefields of the Second World War did not have much choice. Either they killed the enemy, or the enemy killed them. Women at GECO had a different choice. Fill munitions that would ultimately kill, or perhaps die trying.

How did grandmothers, mothers, and young girls justify building weapons that would destroy human life and property? Two hundred and fifty-six million fuses had the potential to obliterate men in not only face-to-face combat, but also to wipe entire towns from the face of the earth.151 Where did women find the resolve to create the means to kill? Moreover, where did they find the courage to work with high explosives that could potentially explode in their hands, ending their own lives? Each GECOite had his or her own reasons for working with high explosives. Carol LeCappelain spoke of a local regiment stationed in North Bay, Ontario, her hometown. Many men from that regiment — her friends and neighbours — were overseas fighting and she felt compelled to help, even if that meant taking lives to save lives.152 Carol was diligent in her inspection duties at GECO. “I didn’t want any soldiers killed due to faulty ammo,” she said, and she hoped that “maybe we had done some good for the men.”153

“I had too much time on my hands with my men away,” GECOite Peggy MacKay said when explaining why she worked at GECO.154 “I felt too that it would help my country.”155 Molly Danniels, while a young woman at GECO, recognized the dangerous nature of the work she did — handling detonators the size of her pinky fingernail. “If you punctured one, it blew up,” she said.156 In hindsight she couldn’t do it today.157

Hartley French explained his stint at GECO this way: “There was a war on and you were more concerned about your own future than what GECO was about.”158 He added, “There was definitely no certainty that we would win.”159 Toronto hadn’t recovered from the Depression and people were scrambling to find work. Hartley was barely out of his teenage years and his focus was on seeking employment while pursuing an education. He was concerned about what would happen to him after he finished school.

Perhaps the best motivation for GECOites to build instruments of death and destruction was the letters from husbands and sons fighting overseas. The following letter arrived at the home of a GECO worker from her twenty-year-old son who was at sea and had been torpedoed. He had been bombed in the London Blitz as well while on leave.

… Mum, I am nearly bursting with pride at the thought of the work you are doing; it makes this job seem child’s play by comparison. I hear so much both from letters from Canada and fellows I meet over here who have heard about you in their letters from home. If the Empire would follow your lead this war would not last long. This may sound like a line but words are useless to express my thanks that I am your son … you have given us something to fight for that other people haven’t got, (not to mention the wherewithal to fight).”160

A young GECOite who worked in Building No. 45 packing filled munitions for shipping felt compelled to send a note of cheer to the men who would receive the shipment.161 Without permission or management’s knowledge, she tucked a note in amongst a box of filled fuses. The note travelled all the way to France where a team of gunners discovered it when they unpacked the ammunition.162 The soldiers wrote back, thanking her for her note of cheer; one fellow going so far as to ask to become pen pals.163

The Whispering Gallery

Rumours and malcontents are a part of any organization. Rumours within a secret munitions factory tended to be tastier, and the tongue-wagging work of mischief-makers was more insidious than their non-military counterparts. Management was eager to squash rumours, knowing the damaging effects gossip — whether there was truth in the tidbit or not — could have on their employees’ resolve. “Whispering Gallery,” a regular column in GECO Fusilier’s early issues, featured poems and cautionary tales that appealed to its audience’s tendency to tongue-wag.164 Ross Davis wrote in the paper’s inaugural edition: “If anyone secured any benefit whatever from such rumors as we speak of — if they were harmful to no one — they might be endured with Christian tolerance. But when they produce nervousness in jobs that call for steady hands, it’s different.”165 Every employee at GECO had been assigned a job, “a big and increasingly important job,” in securing victory for the free world.166 “It is up to everyone [sic] of us to see that nothing interferes with doing that job to our level best,” Ross continued, including spreading, listening to, and taking any kernel of discontent to heart.167

Seventy years have passed since operations at Scarboro ended, and even though rumours are usually true only in fancy, tall tales told in a war plant still tickle tongues today. Someone started a story that saltpeter (used militarily and commercially in fertilizer, food preservation, and as a component in rocket propellants, fireworks, and gunpowder) was not only in the tea and coffee served in the cafeteria, but also in the salt tablets that the Medical Department offered to employees to combat ill effects from heat and humidity during Canada’s summer months.168 Yet another worrisome story circulated that workers could “catch” tuberculosis from being in close contact with fellow fuse-fillers in workshops since all buildings on the clean side were air-conditioned and windowless.169 To stir dissent during Victory Loan drives, people petitioning for Victory Loan purchases were rumoured to receive a commission.170 Management was swift to squelch the rumour, calling such gossip “slander on patriotic people” and was “unworthy of ‘Scarboro.’”171

Conclusion

Why did GECO work so well? Because its employees were determined to make it work. Why did they buy in? Because extraordinary times called for extraordinary measures. Uncertain times with a precarious future called for sacrifice, not only from Canada but from every man, woman, and child around the world who lived and longed for peace. Bob and Phil Hamilton, along with their entire management team, tirelessly endeavoured to create working conditions that boosted the morale of their employees. Despite a wildcat strike that lasted a few hours, and a few tight-fisted employees who did not participate in Victory Bond drives, nearly all GECO men and women were engaged, interested, and eager to give their best to their work. From plentiful social activities to social events; from fundraising opportunities to blood donor clinics; from day care to beauty classes; singing, not grumbling, echoed through the galleries of GECO.