Chapter 2

The Kingdom of the Plants

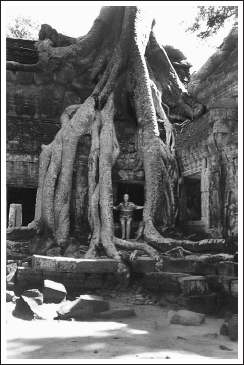

This strangler fig’s roots are now an integral part of the ancient temple at Angkor Wat in Cambodia. I shall never forget the feeling of stepping back in time, the sense of wonder at these extraordinary ruins deep in the forest. (CREDIT: © JANE GOODALL INSTITUTE / BY MARY LEWIS)

Science divides the natural world into six kingdoms, including the animal kingdom and the plant kingdom. And in both we find huge diversity of form and size and color, and so many fascinating and complex societies. Most people are more familiar with the inhabitants of the plant kingdom, for they are all around us, just about all the time. I have spent a lifetime loving plants, even though I have never studied them as a scientist. And over the years, people have given me marvelous books—collections of photographs of various habitats, and of exotic fruits and seeds and flowers that might have been drawn from the imagination of artists high on psychedelic drugs.

I have walked through forests in many parts of the world and marveled at ancient trees festooned with vines, ferns spreading their graceful fronds beside fast-flowing streams, and rocks clothed in mosses. I have a special love for old-growth forests with their wealth of interconnected life-forms—I always feel that I belong there. But there is so much more to marvel at in the kingdom of the plants. I often use the zoom setting of my camera to photograph the exquisite flowering of tiny plants that most people walk past or trample on, not noticing.

The first time I visited the tundra, in Greenland, I was humbled to see small plants that had sprung into life after enduring eight months under snow and ice. And amazed to learn that they were actually trees—but although they had managed to survive in those bleak conditions they could never attain the typical height of their species. How different that arctic habitat is from the exotic riot of color, the sheer enchantment, of an alpine meadow in spring, with its myriad of flowers, the humming and buzzing and droning as a host of insects feast on nectar, pollinating the flowers so that they will reappear next year.

When I first saw the spring flowers blanketing the California hillsides, I wanted to walk out among the lupines and poppies and wild mustard, and simply lie among them, looking up into the blue, blue sky. But I was restrained, warned of snakes among the flowers, and had to be content just to feast my eyes on their colors and inhale their sweet fragrance.

The plants of the arid parts of the world—the dry plains and the desert—are also fascinating. These are the places where succulents and cacti have adapted to survive long periods without water, storing it in their leaves and stems and roots. Just this past spring I spent a couple of hours wandering in the semidesert of Santa Fe, New Mexico, utterly captivated by the strange shapes of the cacti. I was lucky, for most of them were in bloom, their yellow and red and deep-purple flowers like gifts from Mother Nature in the dry landscape. And I have marveled to see how, after a long period of drought, the first rains will carpet the Serengeti Plain of East Africa with white and golden flowers shining through the dry, trampled grass. Here and there the vivid coral-colored flowers of the aloe plants peek through.

Recently, as I drove from Johannesburg to Nelspruit, in South Africa, I desperately wished there was time to stop off and find an elephant root tree (Elephantorrhiza elephantina), which, presumably able to withstand the cold, dry winters of its harsh upland habitat, lives almost entirely under the ground. If you walk among the branches of what seem like small bushes, rising only some three feet above the ground, you will actually be walking on the canopy of a very large and very ancient tree that is mostly out of sight beneath you.

It would be absurd in a book like this to try to describe the fantastic variety of plants, from the tiny mosses to the mighty redwoods. A recent inventory lists 298,000 different plant species (and 611,000 species of mushrooms, molds, and other fungi). And the authors reckon that as many as 86 percent of all plant and animal species on land, and up to 91 percent in the seas, remain unnamed. All I can do here is to share some of what I find particularly compelling about this vast and wondrous kingdom of the plants.

Roots

Wouldn’t it be fantastic if we had eyes that could see underground so that we could observe everything down there in the same way that we can look up through the skies to the stars? When I look at a giant tree, I marvel at the gnarled trunk, the spreading branches, the multitude of leaves. Yet that is only half of the tree-being—the rest is far, far down, penetrating deep beneath the ground. The roots. Bit by bit they work their way through the substrate, pushing aside small pebbles, growing around big rocks, coiling around one another, taking from the soil the water and minerals needed by the partner up above, and creating a firm anchor for it. In many trees, the roots go as deep below the ground as the height of the tree above the ground, and spread out about three times farther than the spread of the branches. One root system, recorded during excavation of a building site in Arizona, had grown down some two hundred feet.

Some of the so-called “weeds” that colonize our gardens as unwanted guests have very deep roots. The dandelion goes down so far it is almost impossible to get the whole thing out of the ground. I can see my grandmother Danny now, kneeling on her little rubber pad, digging down around the roots of one dandelion plant after another, then trying to yank them out of the ground with that tool that looks like the end of the hammer that you use to pull out old nails. But she never got the whole root out.

There are so many kinds of roots. Aerial roots grow above the ground, such as those on epiphytes—which are plants growing on trees or sometimes buildings, taking water and nutrients from the air and rain—including many orchids, ferns, mosses, and so on. Aerial roots are almost always adventitious (I called them “adventurous” when I was a child), roots that can grow from branches, especially where they have been wounded, or from the tips of stems. Taproots, like those of carrots, act as storage organs. The small, tough adventitious roots of some climbing plants, such as ivy and Virginia creeper, enable the stems to cling to tree trunks—or the walls of our houses—with a viselike grip.

In the coastal mangrove swamps of Africa and Asia I have seen how the trees live with their roots totally submerged in water. Because these roots are able to exclude salt, they can survive in brackish water, even water that is twice as saline as the ocean. Some mangrove trees send down “stilt roots” from their lowest branches; others have roots that send tubelike structures upward through the mud and water and into the air, for breathing.

Then there are those plants, such as the well-known mistletoe, beloved by young lovers at Christmastime but hated by foresters, that are parasitic, sending roots deep into the host tree to steal its sap. The most advanced of the parasitic plants have long ago given up any attempt at working for their own food—their leaves have become like scales, or are missing altogether.

The strangler fig is even more sinister. Its seeds germinate in the branches of other trees and send out roots that slowly grow down toward the ground. Once the end touches the soil, it takes root. The roots hanging down all around the support tree grow into saplings that will eventually strangle the host. I was awestruck when I saw the famed temple at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, utterly embraced by the gnarled roots of a giant and ancient strangler fig. Tree and building are now so entwined that each would collapse without the support of the other. I noticed that strangler figs have been at work on many of the Mayan ruins in Mexico as well.

The so-called clonal trees have remarkable root systems that seem capable of growing over hundreds of thousands of years. The most famous of them—“Pando,” or “The Trembling Giant”—has a root system that spreads out beneath more than one hundred acres in Utah and has been there, we are told, for eighty thousand to one million years! The multiple “stems” (meaning the tree trunks) of this aspen colony age and die, but new ones keep coming up. It is the roots that are so ancient.

One of the most important things about roots is that they hold the soil in place. When the early settler farmers moved onto the American prairies, they cut down the trees that grew there and plowed up the land, destroying the native grasses so that they could grow agricultural crops. Over countless thousands of years those native grasses had developed root systems that delved deep, deep into the ground, holding the soil together so that it could withstand the constant stress of the wind. Human interference in this ancient system led to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, when the soil was blown away in great clouds, much of it ending up in far-off oceans. Something similar happens in China today, where clouds of dust are blown from the deforested center of the country and darken the skies over faraway Beijing for days on end.

Leaves

I always love to walk through the trees in the evening, when the sun is low and the leaves are backlit. And each single leaf so beautiful with all its veins etched so clearly, some with an incredibly intricate branching pattern. These veins are the end point of the system that carries water and nutrients up, up from root to leaf. And they are the start of the system that carries the sap, with its dissolved sucrose, back out of the leaf to provide nutrients to the mother tree.

When I was a child, I used to spend hours searching under the trees, looking for the skeletons of leaves—when all the soft material has rotted away and only the veins remain. It is rare to find a perfect one, without tear or holes, but it is worth searching diligently—for the one that is without blemish is truly a work of art. I still search when I am walking through the Gombe forests.

The variety of leaves seems almost infinite. They are typically green from the chlorophyll that captures sunlight, and many are large and flat so as to catch the maximum amount. Indeed, some tropical leaves are so huge that people use them for umbrellas—and they are very effective, as I discovered during an aboriginal ceremony in Taiwan, when we were caught in a tropical downpour.

Orangutans have also learned to use large leaves during heavy rain. My favorite story concerns an infant who was rescued from a poacher and was being looked after in a sanctuary. During one rainstorm she was sitting under the shelter provided but, after staring out, rushed into the rain, picked a huge leaf, and ran back to hold it over herself as she sat back in the dry shelter!

Some leaves are delicate, some are tough and armed with prickles, yet others are long and stiff, like needles. The often-vicious spines of the cactus are actually modified leaves—in these plants it is the stems that capture the energy from the sun. I used to think that the brilliant red of the poinsettia and the varied colors of bougainvillea were flowers, but of course they are leaves adapted to attract pollinating insects to the very small insignificant-looking flowers in the center. And there are those leaves adapted to capturing insects, some covered with resin-tipped glands that curl over and imprison the prey, others able to snap shut in an instant when an insect touches the hairs, which act as triggers.

And then there are the most extraordinary leaves of that bizarre plant, Welwitschia mirabilis. Each adult plant has only two leaves. When the seed germinates, it produces two cotyledons—embryonic first leaves. These survive only until the first true leaves have grown big enough. They look ordinary enough, these two long leaves. But they are not. For they continue to grow, those exact same two leaves, for as long as the plant lives—which can be more than a thousand years.

The Welwitschia was first discovered in Africa’s Namib Desert by Dr. Friedrich Welwitsch in 1859, and it is said that he fell to his knees and stared and stared, in silence. He sent a specimen to Sir Joseph Hooker, at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew—and Sir Joseph for several months became obsessed with it, devoting hours at a time to studying, writing about, and lecturing about the botanical oddity. It is, indeed, one of the most amazing plants on Earth, a living fossil, a relict of the cone-bearing plants that dominated the world during the Jurassic period. Imagine—this gangly plant, which Darwin likened to a duckbill platypus of the vegetable kingdom, has survived as a species, unchanged, for 135 to 205 million years. Originally its habitat was lush, moist forest, yet it has now adapted to a very different environment—the harsh Namib Desert.

The photograph in the color insert shows what looks like many untidy leaves, but they are really only the two. They first appear as the seed germinates—and as the years pass, they become increasingly leathery and tattered, nibbled by animals and buffeted by the wind—but they are never replaced. The tallest plant known is only five feet high; most are no more than twenty inches. Some Welwitschia plants growing in the wild have been carbon-dated and are between five hundred and six hundred years old, but it is thought that some of the largest could be two thousand years old.

Capturing Sunlight

At school I had to learn in my biology lessons about photosynthesis—which literally means “synthesis with the help of light.” When I looked at my son’s biology textbook some thirty years later, I was amazed—and shocked actually—by the complex chemical process that he was supposed to learn as a schoolboy. It was the sort of information that was once reserved for university students specializing in botany—the kind of stuff that would have totally disenchanted me from the wonder of plants. And, indeed, it is pure chemistry.

The point is that plants can capture energy from sunlight. I love how this was described by the German surgeon Julius Robert Mayer in the 1800s. Nature, he said, has solved “the problem of how to catch in flight light streaming to the Earth and to store this most elusive of all powers in rigid form.”

Plants do this through extremely complex chemical reactions, which can, however, be described quite simply. There are special cells, usually in the leaves, that store chlorophyll molecules. This is the source of their green color. These chlorophyll molecules interact with nearby carbon dioxide (CO2) (which they absorb from the atmosphere) and water (delivered by the plant’s roots) to synthesize glucose and oxygen. The glucose is either used at once, for energy needed by the plant, or it is changed (by another complex chemical process) into starch, which is stored until the plant needs it. Meanwhile oxygen, which is actually considered a “waste product,” is released into the atmosphere, where animals and plants use it for their respiration. It amused me, when I read about this, to think of our so-precious oxygen as a “waste product”—that is chemistry talking. The small amount of CO2 produced by the plants during their respiration (basically their exhalations) is quickly used up by the ongoing photosynthesis process.

Think about all this for a moment. Our exhalations are nourishing the plants as they capture CO2, and the plants’ exhalations allow us (and them) to breathe. How utterly amazing—awe-inspiring really. One cupful of CO2, a few tablespoons of water, mixed with a beam of sunlight: the ultimate and only recipe for the food that supports all plant life, including algae and other such forms. And since we depend on plants, either directly, by eating them, or indirectly, by eating animals that themselves depend on plants, the process of photosynthesis supports almost all life on Earth.

Carnivorous Plants

I am not a devotee of science fiction books, but John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids, published in 1951, utterly captivated my imagination. “Triffids” are seven to ten feet tall, have three leg-like appendages that can be rooted into the ground, a sort of trunk, and a funnel-like head containing a sticky substance that attracts and captures insects that are then digested. Within this funnel there is also a stinger that, when fully extended, can measure up to ten feet. Sometimes a triffid will shuffle along the ground on its “legs” and, when it contacts a person, will aim at the face with its stinger. The victim dies quickly, and the triffid roots itself near the body, which it can digest as the flesh decomposes.

Science fiction, yes, but Mother Nature has designed monsters too—they are smaller, they cannot harm people, but the behavior of some of the carnivorous plants would make terrifying bedside reading for the tiny prey they capture. Take the Darlingtonia pitcher plant, also known as the cobra pitcher or cobra lily. It has a well-developed forked protrusion on the end of the modified leaf that forms the lip of the pitcher, which is designed to capture insects. This protrusion offers a convenient platform on which a flying insect can land, attracted to the nasty smell from inside the pitcher—well, nasty to us but obviously irresistible to the insect.

The hapless prey then slips down the walls, helped on its way by both lubricating secretions and downward-pointing hairs, and falls into the water-and-enzyme soup. The small exit is cunningly curled downward and thus hidden from the trapped insect, which exhausts itself by repeatedly crawling up the many translucent false exits. Eventually it will drown, and as it gradually decomposes, it will be absorbed by the plant. Unlike other pitcher plants, this one does not trap rainwater in its pitcher, but pumps up water from its roots, reabsorbing it if the level gets too high.

This is just one of the plants that have become carnivorous, capturing flies and other insects in a whole variety of ingenious ways and then slowly digesting them in special juices. There are about 630 species in six genera with five different kinds of traps, known as pitfall, flypaper, snap, bladder, and lobster traps. Scientists estimate that they first appeared some two hundred million years ago in marshy, infertile soils that were lacking in essential minerals, especially nitrogen. Only by devising a novel way of getting the necessary nutrients could these plants survive. I get so carried away reading about these cunning plants—it would not be difficult to write a whole chapter about them.

The best known are the pitcher plants, sundews, Venus flytraps, and bladderworts. I remember our biology teacher bringing a sundew to school for us to see. Somehow my imagination had created a much more impressive being, and I was disappointed to see such a tiny plant, though fascinated by its behavior. Each leaf has a number of resin-tipped glands that serve to attract and capture small insects. Our biology teacher placed an unfortunate fly on this trap and we watched as the leaf curled slowly over it.

There is one carnivorous genus, Roridula, that has just two species. They are small shrubs with leaves covered by sticky resin glands. The plant cannot absorb or digest the insects that it catches, but it has a partner, an insect similar to and usually referred to as an assassin bug (Pameridea, to give it its proper name). The bug is impervious to the resin because of its thick, greasy covering. It waits among the leaves and quickly pounces on less fortunate insects, then settles down to suck out their innards. Subsequently it produces dung—and it is this that the plant is able to absorb.

One of these plants, growing in the botanical gardens of Leiden University, once captured a jay! My Dutch botanist friend Rogier van Vugt told me how he had to rescue the bird—with great difficulty! Of course, says Rogier, “Neither the plant nor the insects would eat a bird, but it shows how strong the resin is.”

Seeds and Fruits

If plants could be credited with reasoning powers, we would marvel at the imaginative ways they bribe or ensnare other creatures into carrying out their wishes. And no more so than when we consider the strategies devised for the dispersal of their seeds. One such involves coating their seeds in delicious fruit and hoping that they will be carried in the bellies of animals to be deposited, in feces, at a suitable distance from the parent.

Charles Darwin was fascinated by seed dispersal (well, of course—he was fascinated by everything) and he once recorded, in a letter, “Hurrah! A seed has just germinated after twenty-one and a half hours in owl’s stomach.” Indeed, some seeds will not germinate unless they have first passed through the stomach and gut of some animal, relying on the digestive juices to weaken their hard coating. The antelopes on the Serengeti Plain perform this service for the seeds of the acacia.

In Gombe the chimpanzees, baboons, and monkeys are marvelous dispersers of seeds. When I first began my study, the chimpanzees were often too far away for me to be sure what they were eating, so in addition to my hours of direct observation I would search for food remains—seeds, leaves, parts of insects or other animals—in their dung. Many field biologists around the world do the same.

Some seeds are covered in Velcro-like burrs (where do you think the idea of Velcro came from, anyway?) or are armed with ferocious hooks so that a passing animal, willy-nilly, is drafted into servitude. Gombe is thick with seeds like this and I have spent hours plucking them from my hair and clothes. Sometimes my socks have been so snarled with barbs that, by the time they are plucked out, the socks are all but useless. Some seeds are caught up in the mud that waterbirds carry from place to place on their feet and legs.

I wonder how many dandelion “clocks” are picked and blown by lovesick adolescent girls: “He loves me, he loves me not. He loves me, he loves me not,” and calculating the strength of the last breaths so that they can end, triumphantly, “He loves me!” Those little seeds, each suspended from a perfect parachute, are carried away in the thousands by the summer and autumn winds, colonizing gardens and parks—almost anywhere that plants can grow—and often where they are most definitely not wanted.

The kapok seed floats through the air attached to the softest white fluff. I watched one chimpanzee infant as he gazed, as though entranced at this spectacle, then reached out to try to catch some. I sometimes do the same! And I have always loved to watch the seeds of the sycamore trees growing in Bournemouth as they set off on their journey in pairs, fastened between two propeller-shaped wings that spin around and around like the blades of a miniature helicopter as they spiral down toward the ground.

Other seeds, lacking such convenient mechanisms, rely on their pods to shoot them as far away as possible. From my window, at school, I could hear the little pops of the broom pods as they burst open when the seeds were ripe inside and the sun was warm. They were carried several feet—and sometimes ants then carried them farther—which was an advantage only for those that were not eaten. The pods of some plants reach such a state of tension when their seeds are ripe that they seem literally to explode at the slightest touch—like the touch-me-not balsam. And there is a plant in Gombe that splits open, with a loud crack, at the first drop of rain, sending out seeds in all directions. I used to collect these pods and take them to my son, when he was little, and arrange a show for him.

Seeds come in all shapes and sizes. Most are quite small, but not so the coconut. This giant can be carried for miles across the ocean and, in this way, has enabled coconut palms to colonize almost every tropical island.

Sex Education

Plants reproduce both sexually and asexually. Every gardener knows how a cutting, given by a friend, can grow roots and survive. This is how my second husband, Derek Bryceson, and I built up our garden in Dar es Salaam. Some plants, such as the blackberry, form adventitious roots when the tip of a stem arches over and touches the ground. At this place a new plant will grow. Then there are those that send out special stems that are called runners when they grow over the ground, like strawberries, or rhizomes when they grow under the ground, like buttercups. When the runner, or rhizome, is far enough away from the parent plant, the tip puts out roots from which new plants can grow.

There is no doubt whatsoever that this kind of asexual, or “vegetative,” reproduction can be an immensely efficient strategy. And when plants are introduced to new environments, it can also be very destructive. The water hyacinth is a free-floating aquatic plant with attractive lavender or pink flowers. It originated in South America, but has been introduced widely in tropical and subtropical areas of North America, Asia, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. It reproduces asexually by runners and is one of the fastest-growing known plants—it can double its population in just two weeks. It clogs waterways and lakes. It starves water of oxygen, killing fish, turtles, and other wildlife. It was actually grown on lakes in World War II to fool Japanese pilots into thinking they could land. Governments have spent a great deal of money in their efforts to control the water hyacinth.

However, while reproduction without sex may be efficient, it doesn’t allow for genetic diversity, and so almost all plants can reproduce sexually as well. We know all about human sex (way too much, in some instances). Most of us are familiar with the couplings of dogs (cats are far more discreet and usually do their thing at night). Country people know about farm animals, and naturalists have found out a great deal about the mating behavior of countless wild mammals, birds, and insects. Much of all the above involves courtship, which may be elaborate. And we have come to realize, with all this private life exposed by patience, binoculars, and DNA analysis, how much cheating goes on.

What about plants? We can hardly suppose that plants could enjoy sex—but who knows? Maybe, one day, a scientist will detect something akin to the endorphins that are produced in humans during pleasurable experiences (including excitement, love, and orgasm) in some part of a plant when bees are tickling its stamens or brushing against the pistil while it is being pollinated. Nothing in the plant world would really surprise me—but it does seem unlikely. So for now I will stick to the plain and obvious facts.

The bladder wrack, a common seaweed, was well known by us as children. We loved to walk along the beach at low tide when a storm had cast lots of seaweed onto the beach. We would seek out the strands of bladder wrack and stamp on the partially dried bladders, which made a marvelously satisfying popping sound (the same as when you pop the air bubbles of Bubble Wrap). It is at the tips of these bladders that the sperm and eggs are stored. There are male and female bladder wracks, and reproduction takes place only once a year, when both sperm and eggs are released into the water at the same time. Fertilized eggs sink to the bottom of the sea and soon attach themselves to some hard surface.

Flowering plants, of course, have the most complex reproduction. And it is the love of flowers, of the blossoms with their staggering variety of shape, color, and size, that have so bewitched people over the ages. The largest single bloom in the world is that of the “corpse flower” (Rafflesia arnoldii) of Sumatra—it may measure a yard across and weigh as much as fifteen pounds. The flowers actually look and smell like rotting flesh, which is why it’s commonly known as the corpse flower. The smallest, by contrast, is that of the tiny water weed Wolffia, which measures a mere .01 inch across. And, too, there are the perfumes, the sometimes-intoxicating scents produced by flowers, especially those that are put out at night to attract moths and other night pollinators. Even bats.

Flowers are equipped with female and male organs, the pistil and the stamen. The stamen produces the pollen, which must somehow reach the pistil so that the waiting undeveloped seeds can be fertilized. This happens when pollen grains pass through little openings (stigma) at the tip of the pistil and travel down a tube (the style) to the ovum at its base.

The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus discussed this in his famous work on the classification of plants. He was dismayed when he learned that one of his articles, translated into English, was banned because it was “lewd and salacious”—“stamen” and “style” had been translated with the words husband and wife. One plant was thus described as having four husbands, two taller than the others; another had twenty husbands or so in the same marriage! At any rate, irrespective of the number of husbands, successful pollination results in the development of a seed.

The countless and cunning ways that plants have devised to get the pollen grains with their live sperm from stamens to pistils are absolutely awesome. Some release their pollen in large quantities, sometimes explosively, into air or water with the hope that it will be transported by the currents of air or water to the waiting pistils. As I write this, the pollen from the pine trees in our garden is being carried by the breeze in yellow clouds. The ground, the cars, our clothes—everything is covered with fine yellow dust. Bad luck for those who suffer from allergies.

Other plants have opted to have their pollen transported by a variety of animals, who are lured into service by enticing fragrances, delicious nectars, and attractive colors. Many kinds of insects serve as pollinators—and so do birds such as hummingbirds, occasionally bats, and even, it has been suggested, small amphibians. Some plants, including many orchids, have very specific needs—only one species of wasp pollinator will do.

Probably the first pollinating insect that springs to mind is the bee. I already described how I loved to watch the bees in the glorious summer days of childhood as they buzzed from flower to flower, probing for nectar and gathering golden pollen on their back legs in what we called their “breadbasket.” This was the bee benefiting from the flower, obtaining the ingredients for making honey and “bee bread” to feed the young back in the hive. But at the same time, as the bees moved from one bloom to the next, pollen was repeatedly brushed off onto the outstretched pistils. So the flowers were achieving their goal as well.

Not all insects are attracted by glorious scent or alluring nectar—certain plants cater to the preference of those that prefer a “fragrance” most horrid to our senses. The titan arum, which stands about six feet tall, and the corpse flower (Rafflesia arnoldii) of Sumatra, which, as mentioned, has the biggest single bloom in the world, both emit a stench that is irresistible to those flies and beetles that eat or lay their eggs on rotting flesh. I well remember when a titan arum was in bloom at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and lines of people gathered for the dubious thrill of experiencing its vile smell.

Defense Strategies

The other day I watched a cow feeding in a field. She was chewing her way through grass and a whole lot of herbs. There was clearly nothing the plants could do about it. Or was there? There were a few clumps of ragwort in the field, and I noticed how the cow avoided them. She clearly knew, somehow or other (from a bad experience or instinctive reaction to the toxins in its scent), that this plant was poisonous.

Plants are unable to run away or fly, so unless they develop some kind of defense, such as poison, they are liable to become someone’s breakfast, lunch, or dinner. In fact, plants have developed a whole host of ways to protect themselves. Some simply taste nasty, and some of the nasty ones are actually as poisonous as the ragwort is to cows. Deadly nightshade, so often mentioned in the old storybooks, is even more poisonous to us than is the ragwort—children can die from eating as few as three berries—but many birds eat it without any ill effect.

Unfortunately for the ragwort, the caterpillars of the cinnabar moth have become resistant to this poison and live on the leaves. This is, of course, what happens when we spray pesticide on farms or gardens—some insects become resistant, so other forms of poison must be concocted. In nature there is usually a balance so that if an insect predator proliferates unduly, its plant food will diminish to the point where the insect numbers cannot be sustained. And when the predators are then reduced, the plants can make a comeback. Then the whole predator/plant cycle can start again.

Poison is not the only defense—plants have evolved a great variety of other weapons, many of which I learned about as a child as a result of personal experience. Holly trees have leaves with sharp prickles, as we realized each Christmas when collecting some for decorating the rooms, placing sprigs with their bright-red berries behind every picture—and one on the Christmas pudding. When we went picking blackberries in the summer, we returned with arms and legs scratched and bleeding from the thorns on the stems—and it was the same when I picked wild roses, desperate to capture their fragrance and take it home with me.

Nettle leaves are covered with fine stinging hairs. And they are vicious—my mother told me about her time as a schoolgirl when a bullying gang of older girls, which included, I regret to say, her older sister Olly, threw her into a bed of stinging nettles. Fifty years later she still remembered the pain with horror. Even the traditional remedy—pressing dock leaves onto the affected area—did not help such widely tortured skin.

Plants have evolved a variety of impressive defenses. How on earth can this infant vervet monkey move about in this acacia tree with its formidable thorns?! It’s even more incredible to see giraffes eating them. The photo was taken in Lake Manyara National Park in Tanzania. (CREDIT: © THOMAS D. MANGELSEN/WWW.MANGELSEN.COM)

My childhood was free of the two scourges of the American woodlands—poison ivy and poison oak. I have only once had a close encounter with poison ivy—I was fortunate, for it hardly bothered me, although the person I was with was badly affected. I have, however, had many unpleasant experiences with a small and very inconspicuous plant at Gombe that has tiny leaves covered, like those of a nettle, in stinging hairs. And when, intent on watching a chimpanzee, you inadvertently sit on one of these plants in the wet season, the burning itching lasts for well over a day—it is extremely painful. How on earth the minute stinging hairs can attack through two layers of cloth I simply cannot imagine.

I learned a lot about the defenses of the plants that flourished in the Olduvai (or Oldupai) Gorge in Tanzania when I worked there for three weeks in the dry season of 1957. In the daytime I was digging for fossils, along with Mary and Louis Leakey. But every evening, Gillian (the other English girl on the expedition) and I were allowed to wander in the gorge and onto the plains. And there we learned to know and respect the vicious thorns of the acacia trees—and marvel at the sight of a giraffe munching on the spiky foliage with impunity.

We also encountered the wild sisal (Sansevieria ehrenbergii). Indeed, it grows there so prolifically that the Masai, who call it “oldupai,” named the gorge in its honor. A close encounter with those strong spiked leaves, so beloved by the rhino who lived there then, left wounds in our skin that hurt and itched for hours, though we were soothed a little if the wounds were smeared with the sap from a cut leaf. There were euphorbia there too, and one evening, as we sat around the campfire, Louis told us how baboons can chew the leaves of the euphorbia for moisture—but that one man, desperately thirsty, almost died when he thought it would be okay for him to do the same. His throat and tongue swelled up so that he could hardly breathe, and he was lucky to survive, for the milky sap, or latex, can be deadly.

Some plants have another extraordinary adaptation to protect not only themselves but also each other from attack by predators—they communicate with each other.

Communication between Plants

The very idea of plants communicating with each other is normally treated with skepticism. Yet new research is substantiating claims, initially made in the 1980s, that some of them actually can. And in two ways: through airborne chemical molecules released by the leaf, and underground, through their roots.

In the early 1980s David Rhoades, a scientist from the University of Washington, announced at a conference his belief that trees were able to communicate with each other. If an herbivorous insect attacked a tree, nearby trees were alerted, most probably through airborne chemicals released by damaged leaves. These airborne chemicals, Rhoades suggested, triggered chemical defense mechanisms in neighboring trees. When I heard about this, I was really excited, and included the information in many of my lectures at the time, although the idea was ridiculed by most scientists.

But gradually the notion of tree-to-tree communication gained credence. In 1983, Dartmouth biologist Jack Schultz and his research assistant Ian Baldwin published a paper in Science that provided evidence of this type of communication between poplar trees and between maples. Rhoades was able to pronounce, triumphantly, “Trees have a few tricks up their leaves—they aren’t static things just waiting to be eaten.”

Meanwhile another research team, from Ben-Gurion University, in Israel, led by biologist Ariel Novoplansky, has shown that distress signals can be communicated plant to plant through their root systems (although the exact mechanism had not yet been worked out). In one study, published in the spring of 2012, five domestic pea plants were subjected to stressful drought conditions. This caused the plants to close their leaves to prevent water loss. At the same time signals were sent out, through their roots, and were picked up by neighboring unstressed plants—which then reacted as though they, too, were suffering drought conditions.

The fact that information of this sort can be sent, received, and stored by plants has profound implications. Novoplansky explained it this way: “The results demonstrate the ability of plants and other ‘simple’ organisms to learn, remember and respond to environmental challenges in ways so far known only in complex creatures with a central nervous system.”

Amazingly, the scientists found that the nonstressed plants that had nevertheless reacted in the same way as their water-deprived neighbors subsequently coped better, when exposed to the stress, than naïve plants.

It reminds me, in a way, of the impact of some of my early discoveries about chimpanzee behavior. In the 1960s science (and religion) believed that humans were the only beings on Planet Earth with personalities, minds capable of thought, and emotions. In other words, we were the only sapient, sentient beings. Research on the chimpanzees at Gombe showed that this was not true and that humans were indeed part of the animal kingdom. Plants have their own magical kingdom, and it certainly does not surprise me that they are capable of communicating in ways once thought unique to complex animals.

Another recent study is revealing a different kind of communication through roots—which also has far-reaching implications. Millions of years ago a fascinating partnership was forged between plants and a unique group of organisms living in the soil, the mycorrhizal fungi. Today, the roots of about 95 percent of all plant species are coated with these threadlike fungi, which act as a kind of secondary root system, creeping way out into the ground, extracting water and minerals. They share these vital resources with their host plant, which, in turn, provides the fungi with sugars.

Suzanne Simard, a forest ecologist from the University of British Columbia, heads a team that is finding ways to “see” under the ground, and this cutting-edge research shows that the mycorrhizal fungi serve to connect the roots of one tree to another, creating an underground network deep down under the forest floor.

Their study site is a Douglas fir forest, and here graduate student Kevin Beiler used a new DNA-reading technology to distinguish between different individual fungi and the roots of different individual trees. It is now clear not only that all the trees in the forest are interconnected below the ground but also that each of the largest and oldest trees serves as a “mother tree,” with younger trees growing within her root-fungi network.

What I find absolutely fascinating is the fact that the “mother tree” sends carbon, nitrogen, and water along her roots, and while these nutrients are absorbed by the fungi, some are passed on, through the fungi’s interconnected threadlike strands, to the roots of seedlings that, living in the gloom of the forest floor, desperately need them. When a mother tree is cut down, this is likely to have an adverse effect on the development of the young, replacement seedling, and thus the regeneration of the entire forest may be compromised.

It seems there is no end to the plant marvels that are taking place around us.

Plants and Humans—A Love Affair

It is hardly surprising, given the endless variety of plants, their beauty, and their fragrance, that they have captured the imaginations of people through the ages. Indeed, our love affair with plants has been interwoven into human history for centuries. Just recently archaeologists discovered that a Bronze Age grave, located south of Perth in Scotland, contained a bunch of meadowsweet blossoms. Dr. Kenneth Brophy of Glasgow University commented that while the dried flowers were nothing much to look at, they represent the first indication that people in the Bronze Age were actually placing flowers with their dead. And of course they would have looked much better when they were freshly picked.

“To find these very human touches is something very rare,” he said, and he suddenly felt that what he was looking at was “not just a series of abstract remains.”

Why were the flowers there? Did those Bronze Age people want to ensure that the dead would have flowers in the afterworld? Were the meadowsweets a favorite flower, something the deceased would enjoy in another world?

How exciting it must have been to find the dried remains of a bouquet of meadowsweet blossoms in a Bronze Age grave, indicating that the people back then were placing flowers with their dead. (CREDIT: UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW)

In ancient Rome the ground around a grave was sometimes laid out like a garden so that the soul of the departed might enjoy the flowers. Today the custom of leaving flowers on the graves of our loved ones is widespread, so that many graveyards do, indeed, look like gardens. And it is common practice to throw flowers or petals onto the coffin before the earth is shoveled over it. I have not been able to discover how this custom originated—I suppose it means different things to different mourners.

I was enchanted to learn that in Victorian Britain, when some feelings could not be openly spoken of, the “language of flowers” (floriography) was highly developed. By sending particular flowers, or combinations of flowers, it was possible to send almost any message—and many floriography dictionaries were published. This language of flowers apparently originated in Turkey and spread to many different countries. Even today some flowers are still associated with certain feelings—any woman receiving a bouquet of red roses knows exactly what a man is telling her!

When I was running the research center at Gombe, Derek was director of Tanzania’s national parks. He regularly visited each of them, including Gombe, flying the parks’ single-engine plane. One afternoon I saw the plane flying low over the lake. As it drew level with my house on the beach, it waggled its wings, and Derek threw something out of the window, enclosed in a plastic bag. I waded out into the water to retrieve it. A single red rose! This was shortly before he asked me to marry him.

Plants offer so much to so many. For the scientist there are endless new questions to ponder as modern technologies reveal more facts about plant biology. For the naturalist there is constant opportunity to gain an ever-growing appreciation of the miracles of nature—a simple magnifying glass can open up a whole new world. For the artist—what a richness of material for pen or paintbrush or camera. And for a child there is the magic of a beautiful flower springing from a bulb planted in the soil.

We can all be cheered by the natural beauty that is around us, if only we will look. Even in the busy city streets small plants push bravely up through cracks in the paving. Pause and look at the next one you see, marvel at its determination, its will to live. And give thanks that we live in such a wonderful, magical, and endlessly fascinating kingdom. The kingdom of the plants.