Chapter 3

Trees

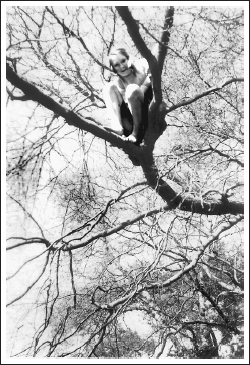

I spent hours in Beech, reading books about Africa and doing my homework. Here I am at about thirteen years old. (CREDIT: SALLY PUGH)

I have always loved trees. I remember once, when I was about six years old, bursting into tears and frantically hitting an older cousin (with my little hands only) because he was stamping on a small sapling at the bottom of the garden. He told me he hated trees because they “made wind”! Even at six years of age I knew how wrong he was. I have already mentioned the trees in my childhood garden—the most special was a beech tree. I persuaded Danny to leave “Beech” to me in a “Last Will and Testament” that I drew up, making it look as legal as I could, and she signed it for me on my eleventh birthday.

I loved Beech so much I persuaded my grandmother Danny to give me Beech on my fourteenth birthday.(CREDIT: JANE GOODALL)

I spent hours up that tree, perched in my special place. I had a little basket on the end of a long piece of string that was tied to my branch: I would load it before I climbed, then haul up the contents—a Tarzan book, a saved piece of cake, sometimes my homework. I talked to Beech, telling him my secrets. I often placed my hands or my cheek against the slightly rough texture of his bark. And how I loved the sound of his leaves in summertime: the gentle whispering as the breeze played with them; the joyous, abandoned dancing and rustling as the breeze quickened; and the wild tossing and swishing sounds, for which I have no words, when the wind was strong and the branches swayed. And I was part of it all.

During the first four months at Gombe I was with my mother—for the authorities would not allow a young woman to be on her own in such a remote area. But when she had to return to England, people had come to know me and considered I would be fine staying on with my two staff. And, as weeks became months, I gradually felt ever more at home in my new world.

Often, when I walked alone up to the Peak—the observation point from which, using my binoculars, I could usually locate the chimpanzees—I would pause to talk to some of the trees I passed each day. There was the huge old fig tree, with great wide branches, laden with fruit and feasting chimpanzees, monkeys, birds, and insects in the summer, and the very tall and upright mvule, or “dudu” tree, which attracted chimpanzees to feed on white galls made by a lace bug in the spring. Then there were the groves of the mgwiza, or “plum tree,” that grew near the streams, and the mbula and msiloti of the open woodlands, all of which provide, in their seasons, plentiful food for the chimpanzees—and other creatures too.

I became increasingly aware of these trees, and many, many more, as beings. I loved the feeling of the rough sun-warmed bark of my old fig, and the cool, smooth skin of my dudu tree. I seemed to know the movement of the sap as it was sucked up by unseen roots and drawn up to the leaves high overhead, where it mixed with CO2 and sunlight to provide the trees with their nourishment.

I had a special bond with some of the young, eager saplings thrusting determinedly toward the canopy and seeking their share of the good light and life up there. They reminded me of myself, and I wished them luck.

Of all the trees at Gombe, it was the gnarled old fig tree that I loved best. How long had he stood there? How many rains had he known and how many wild storms had tossed his branches? With modern technology we could answer that question. We even know, today, when the first trees appeared on Planet Earth.

When Trees Began

From the fossil record it has been suggested that trees appeared about 385 million years ago, about 100 million years after the first plants had gained a foothold on the land. I can well imagine the excitement of the scientists working at a site in Gilboa, New York, who, in 2004, discovered a four-hundred-pound fossil of the cladoxylopsid Wattieza, which was the crown of a fernlike tree. The following year they found fragments of a twenty-eight-foot-high trunk. And suddenly they realized the significance of the hundreds of upright fossil tree stumps that had been exposed during a flash flood over a century earlier. Those tree stumps were just ten miles away from their site and were estimated to be 385 million years old. This fernlike tree trunk and its crown thus became collectively known as Eospermatopteris.

This is a reconstruction of Eospermatopteris, a fernlike tree, that appeared 140 million years before the first dinosaurs. Eospermatopteris forests sent roots into the hard surface, preparing the way for the proliferation of the land animals that followed. (CREDIT: FRANK MANNOLINI/NEW YORK STATE MUSEUM)

It seems that these treelike plants spread across the land and began the work of sending roots down into the ground, breaking up the hard surface and eventually forming the first forests. And as their numbers increased, they played an increasingly important role in removing CO2 from the atmosphere and cooling Devonian temperatures. Thus they prepared things for the proliferation of land animals across the barren landscape of the early Devonian.

The Archaeopteris, which flourished in the late Devonian period, is the most likely candidate so far for the ancestor of modern trees. It was a woody tree with a branched trunk, but it reproduced by means of spores, like a fern. It could reach thirty feet in height, and trunks have been found with diameters of up to three feet. It seems to have spread rather fast, occupying areas around the globe wherever there were wet soils, and soon became the dominant tree in the spreading early forests, continuing to remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

And then there are the “living fossils,” the cycads. They look like palms but are in fact most closely related to the evergreen conifers, pines, firs, and spruces. They were widespread throughout the Mesozoic era, 250 to 65 million years ago—most commonly referred to as the “Age of the Reptiles,” but some botanists call it the “Age of the Cycads.” I remember Louis Leakey talking about them as we sat around the fire at Olduvai Gorge, and imagining myself back in that strange prehistoric era. Today there are about two hundred species throughout the tropical and semitropical zones of the planet.

Once the first forests were established, both plant and animal species took off, conquering more and more habitats, adapting to the changing environment through sometimes quite extraordinary adaptations. Throughout the millennia, new tree species have appeared, while others have become extinct due to competition or changing environments. Today no one knows for sure how many tree species there are in the world. Some estimate as high as one hundred thousand species, while other sources go as low as ten thousand.

The Living Ancients

Certain trees, the so-called “big trees,” have been on this planet for several thousand years. A few years ago I unexpectedly came upon an ancient olive tree, at least eight hundred years old, in the center of one of the open squares in the city of Palma, Majorca. It was strange to see this ancient being, surrounded by the bustle of the town, and I found myself wondering about the hundreds of thousands of people who must have eaten its fruits, sat in its shade, exchanged words of love or anger. And I wondered, too, if this tree, surrounded only by buildings and some introduced grass and flowers, missed those other trees that, at one time, must have grown around it in a shady and peaceful grove.

One time, when I was fortunate to explore the pristine unlogged Goualougo Triangle in northern Congo, I found myself mesmerized by the ancient giant hardwoods. I had no way of knowing how old they were, but standing at the base of one of the huge trunks—so wide that it would take at least four people holding hands to encircle it—and gazing up and up to the canopy where monkeys looked down chattering, I was humbled by the thought of the thousands of years it had stood there. And I imagined the generations of animals—even of the long-lived elephants—that had come and gone beneath their boughs.

And then there were the towering redwoods and Douglas firs and Scotch pines of North America’s West Coast, where I walked, full of wonder, through the forest of giants. I have yet to meet the almost-unreal bristlecone pines that cling to rugged cliffs, their trunks stunted and their limbs twisted into strange contorted shapes by the relentless buffeting of the winds during the past four to five thousand years.

Just last week, out of the blue, I had a letter from Tim Mills, an old friend of mine with whom I had lost touch. As though he knew I was writing about trees (he did not), he told me that one of the things on his “bucket list” had been to meet “Methuselah,” the ancient bristlecone who lived at ten thousand feet in the White Mountains of the Sierra Nevada range in California.

The location is kept secret—the ranger told Tim that he thought only four people know where it is. Somehow Tim and his son managed to find that secret place from an old photo. They confirmed that it was indeed Methuselah when they found that the bore holes on the trunk, made when taking samples for carbon dating, matched those shown on the photo. I wrote back and asked him how he had felt in the presence of a tree said to be 4,845 years old.

Tim replied, “Being among the trees in the Forest of the Ancients was awe inspiring. I walked slower, was very quiet and my senses came awake. There was a reverence akin to being in an ancient church. Finding the Methuselah Tree was an unexpected privilege and we bound ourselves by an oath never to share its location.”

He told me the only bark on the trunk was an eight-to ten-inch strip of cambium layer that spirals up the tree, carrying needed nutrients from the soil up to the leaves above. It is only because of this thin strip of bark that the tree can stay alive.

“Methuselah,” carbon-dated at 4,845 years old. After the destruction of an even older tree, this Methuselah is believed to be the oldest known bristlecone pine. This photo was taken by a friend of mine. (CREDIT: T. J. MILLS)

We often determine the age of trees by counting and cross-referencing tree rings, one for each year. But when some of the wood is missing, and therefore some of the growth rings are gone, the age can be calculated by carbon dating—which involves taking a sample from the innermost part of the tree.

The oldest trees in the United Kingdom are English yews. Many of them are thought to be at least two thousand years old—and it is quite possible that some individuals may have been on Planet Earth for four thousand years, the very oldest being the Fortingall Yew in Scotland. Yew trees were often planted in graveyards—they were thought to help people face death, and early churches were often built close to one of these dark, and to me mysterious, trees.

Almost every part of the yew is poisonous—only the bright-red flesh around the highly toxic seed is innocent and delicious. It was my mother, Vanne, who taught Judy and me that we could join the birds in feasting on this delicacy. How well I remember her telling us this as we stood in the dark, cool shade of a huge yew tree, whose thickly leaved branches cut out the brilliant sunshine outside. The tree grew outside an old church, but, the churchwarden told Vanne, the tree was far older than the church. We plucked the low-growing berries, separating out the soft flesh in our mouths and carefully spitting out the deadly seed.

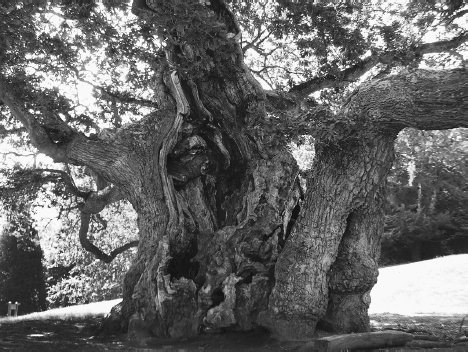

A “Living Ancient.” Some kinds of oak trees can live for up to two thousand years, and they are among my favorite trees. This one, in Jægersborg Dyrehave (the Deer Park) in Denmark, is estimated to be a thousand years old. Two of my friends were actually married inside the hollow interior. (CREDIT: ILKE PEDERSEN-BEYST)

When we think of ancient trees, we tend to think of them as large, but they are sometimes quite small. When trees live in harsh settings, such as arctic cold or desert conditions, they tend to grow very slowly, so it’s hard for people to realize how very special and ancient these trees might be. A friend of mine, the botanist Robin Kobaly, told me that when she was a child, she would pass a wild plum tree every day on her way to and from school in Morongo Valley, a desert area of southern California. It was only about fifteen feet tall, and its trunk was about two feet across.

“I sort of befriended that plant,” Robin told me, “and the California Thrasher that always sang from its upper branches as I walked by.” When she went off to college, she lost touch with her special tree. Forty years later she moved back to the same neighborhood. “And there, waiting to greet me,” said Robin, “was that same wild plum.” It was in one of the few lots that had not yet been developed. She had aged during their separation, but the tree had not changed at all, and she wondered how old it was.

“The way I found out,” Robin told me, “broke my heart.” One morning she awoke to the sound of a bulldozer. She looked out to see her wild plum being ripped from the earth. “I ran down the street to see what remained of that majestic plant. I ended up salvaging the uprooted trunk, and realized I could count the annual growth rings exposed in the split wood—over 350 rings. It amazed me, even after studying desert plants for my master’s degree. How much longer might this ancient plant have lived? Even the bulldozer operator felt bad, and said he could have easily gone around it, as it was in a location that they couldn’t build on anyway. He said he wished he had known.”

After that, Robin began hunting for the trunks of other trees in her area that were being killed. She found junipers over a thousand years old, ironwood trees over eight hundred years old, oaks over five hundred years old, wild plums over four hundred years old, and even the smaller creosote bushes several hundred years old. “But because, in order to survive the extremes of our arid climate, these plants remain small,” she said, “no one realizes how old they are.” Robin has now dedicated her life’s work to educating people about these ancients and protecting them from senseless assaults and destruction that come from ignorance.

Of all the trees in the world, the one I would most like to meet, whose location is top secret, is the Wollemi pine. It was discovered by David Noble, a New South Wales parks and wildlife officer, who was leading an exploration group in 1994, about a hundred miles northwest of Sydney. They were searching for new canyons when they came across a particularly wild and gloomy one that David couldn’t resist exploring. After rappelling down beside a waterfall and trekking through the remote forest below, David and his group came upon a tree with an unusual-looking bark. David picked a few leaves, stuck them in his backpack, and showed them to some botanists after he got home. For several weeks the excitement grew, as the leaves could not be identified by any of the experts. The mystery was solved when it was discovered that the leaves matched the imprint of an identical leaf on an ancient rock. They realized the newly discovered tree was a relative of a tree that had flourished two hundred million years ago. What an amazing find—a species that has weathered no less than seventeen ice ages!

The Wisdom of Trees

Many people, it seems, feel deep respect when they encounter ancient trees. A few years ago I was in Bamberg, Germany, attending an event to celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of a hospital where I was giving a talk. They were anxious to have a tree-planting ceremony to mark the event—but it was the wrong time of year, and the ground was covered in snow. So we had a ceremony at the place where a walnut tree would eventually be planted. The nut was handed to me in a basket, and I handed it over to the head of the hospital to plant on my behalf in the spring. And then came a reading, in German, of some inspired lines by Herman Hesse from his book Bäume. Betrachtungen und Gedichte. It was icy cold with a blue sky and a chill, chill wind, and we got colder and colder as each sentence was translated for my benefit, but I was spellbound by the words. Later my hosts gave me an English translation of their reading:

For me, trees have always been the most penetrating preachers. I revere them when they live in tribes and families, in forests and groves. And even more I revere them when they stand alone. They are like lonely persons. Not like hermits who have stolen away out of some weakness, but like great, solitary men, like Beethoven and Nietzsche. In their highest boughs the world rustles, their roots rest in infinity; but they do not lose themselves there, they struggle with all the force of their lives for one thing only: to fulfill themselves according to their own laws, to build up their own form, to represent themselves.

—Herman Hesse, 1920

When the last word died away, the lead player of the orchestra, who had been keeping his hands warm under a thick anorak, produced a flute. With his hands losing their warmth and his fingers stiffening, with the spit freezing in the pipe, he nevertheless played a beautiful piece of music, also inspired by trees. I can never forget that occasion—standing in the clean, cold air and listening to the haunting sounds of the flute, sounding for all the world like the singing of trees as they endure the winter, knowing the spring will come. I was in a trancelike state when the music ended, slowly awakening to frozen hands and feet, hastening inside for hot mulled wine.

It is hardly surprising that trees were worshiped, venerated for their age and endurance. Cults of tree worship have existed almost everywhere, and there are still sacred woods in India, Bali, Japan, Africa, and undoubtedly other places too. A number of different species have inspired awe throughout the ages. Ancient Egyptians revered the sycamore. They believed that twin sycamores flanked the eastern gate of heaven through which the sun god, Ra, passed every morning. These trees were often planted near tombs, and coffins were made of their wood.

In ancient Greece and Rome there were many sacred groves of olive, ash, and oak, and the Celtic tribes in ancient Britain also revered oak trees that were thought, by some, to be the source of sacred wisdom. Perhaps they are, these old trees. Perhaps we simply need to find a way to understand their message, to hear their voices.

In Nepal, in both the Hindu and the Buddhist religions, the two most sacred trees are the bar or banyan (Ficus benghalensis) and the peepal (Ficus religiosa). Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, the highest gods in Hinduism, are all thought to be present in the peaceful shade of these trees, and in ancient times people would gather under their shade for discussion—often the king and his ministers would administer justice in the presence of the holy trees. It was under a famous Ficus religiosa, also known as the Bodhi Tree, that Buddha received enlightenment. Seedlings from the sacred Bodhi Tree have been transported to many Buddhist nations throughout the world.

A Tree Wedding

I have seen, on several occasions, when driving through Nepal, small clearings at the side of the road that were underneath bar and peepal trees. These are known, I was told, as chautaras, or resting places, for weary travelers. When a bar and a peepal are planted side by side, a symbolic wedding may take place, and the trees are referred to as the bride (peepal) and groom (bar). The marriage is performed with the same sort of enthusiasm, music, and rituals that are observed at a human wedding. Once the trees are married and planted together, it is believed they will bring good fortune.

During one of my visits to Nepal, I was privileged to witness such a ceremony, arranged by one of my friends, Narayan Pahari. He wanted to ensure good fortune for a small weekend cabin that was being built for visitors and Roots & Shoots leaders to escape the terribly polluted air of Kathmandu. We climbed to the building site—a lovely place, nestled on a very steep hillside with a view across the Himalayas.

The “bride” and “groom” were waiting for us, standing there in their earthen pots decked out in their wedding finery of white and yellow silk ribbons. The holes to receive them had been decorated with intricate geometric patterns around the rim, crafted from red and yellow pastes made from crushed flower petals. And amazingly, down in the bottom of each hole, which was perfectly round with straight walls like a well, the same pattern was repeated. An array of symbolic objects was laid out ready for the ceremony—marigold petals, special seeds, and a jar of orange-red vermilion.

The Hindu priest and his five acolytes arrived and began their chanting. One of the plant pots was ritually smashed and bar was placed into his waiting hole. I approached. The senior priest dabbed a vermilion bindi in the center of my forehead, then placed a small amount of the same red paste in my outstretched hands, which I smeared on bar’s leaves. Next he gave me red and yellow petals: after holding them briefly between my hands, pressed together in prayer, I scattered them over the tree.

Next peepal was released and planted in her hole, about eight yards away. The priest blew a conch shell, the acolytes chanted. And then it was over.

By then it had turned very cold, and we returned to the lodge where we were staying, to a lovely warm wood fire and supper. We talked about the ceremony and the way trees can help us connect to the spiritual world. And I dreamed, that night, of how I stood in a forest and one graceful tree bowed down and encircled me with its branches.

Special Friendships with Trees

No one is surprised to hear about close and loving relationships between a human being and an animal such as a dog or cat. But a person and a tree? Surely that is a stretch of the imagination? Or perhaps not. I have described the closeness I felt with Beech when I was a child—it was something over and above my love for other trees. It was up Beech that I climbed when I was sad, and in the long hours I spent among his branches I came to think of him almost as a person with whom I shared my most-secret thoughts. And I listened to his voice in the wind, and even if I could not understand his actual words, who knows what I may have learned?

I think perhaps many people, especially children, develop close feelings for a particular tree. One of my heroes, Richard St. Barbe Baker, whom I shall mention later, devoted his life to protecting and restoring forests. He grew up close to a British oak-and-beech-wood forest. When he was a very small child, about five years old, he went off into the forest alone, and thus began a special relationship with one particular beech tree. She became, he says, a mother confessor to him, his “Madonna of the Forest.” He would stand close to her and imagine he had roots digging deep down into Mother Earth, and that up above were his branches, reaching up to the sky. After such an experience he believed he was imbued with “the strength of the tree.”

And a friend of mine, Myron Eshowsky, who developed shamanic powers later in life, had a dream as an eight-year-old child in which a tree told him it was his brother and they would grow old together. Myron went out searching for that tree until he seemed to hear a young maple, taller than him, calling to him, “I’m here.” Myron managed to dig up the tree, and replanted it at home. But he had damaged the roots, and the leaves began to droop. If my brother dies, he thought, I shall die too. And he would creep out each night crying, praying, and begging the tree to live.

Fortunately his tree brother survived and grew strong, and every so often during the past fifty years, Myron goes to visit that so-special tree.

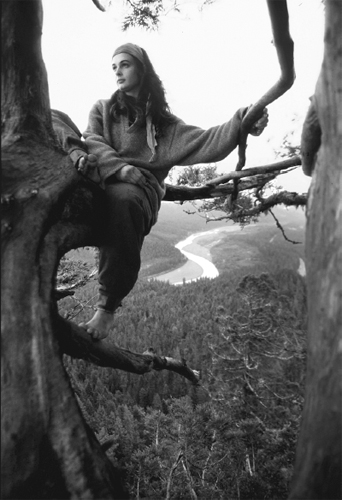

It is not only as children that we form special bonds with trees. There was, for example, the intense relationship between Julia Butterfly Hill and a redwood called Luna, who was two hundred feet tall and approximately one thousand years old. It all started when Julia joined a group that was protesting the clear-cutting of the redwoods in California in 1997. They were taking turns staying up in Luna—Julia was not initially affiliated with the group, and only went up the first time because no one else was volunteering. And she was both scared and exhausted by that first climb. But she soon fell under the spell of the magnificent tree and she stayed up there for a total of 738 days.

Some people form special bonds with trees. Hoping to prevent the clear-cutting of the ancient redwoods, Julia Butterfly Hill spent 738 days living up in the branches of Luna, a 200-foot-tall redwood. Luna, photographed in May 1999, is located in Stafford, California. (CREDIT: SHAUN WALKER)

She defied harassment from the lumber company, who buzzed her with helicopters. She endured torrents of rain, terrifying gale-force winds, and freezing temperatures that gave her frostbite during the coldest winter in northern California’s recorded history. She did not leave until the loggers agreed to spare Luna and her grove of companions.

When Julia finally set foot on the ground again, she felt joy for having saved Luna, but she also felt an inner sadness. Leaving Luna, she said, was like leaving the best friend and teacher she’d ever had. And when, years later, a vandal wounded Luna, she felt deep pain as well as anger.

I recently read an interview with Julia in the January 2012 Sun magazine, where she said she goes back once or twice a year to visit Luna. “The experience taught me that every living thing can communicate,” she told the interviewer. “So I return to let Luna know that I still care.”

Communicating with Trees

I have already written about the ways trees communicate with one another through leaves and their root systems. But can trees communicate with us? It seems absurd to even ask the question—but maybe not.

A couple of years ago I was spending the night in a friend’s house, and picked a book at random from the shelves for bedside reading. It was Under the Greenwood Tree by the British novelist Thomas Hardy, published in 1872. And this is how it begins:

To dwellers in a wood almost every species of tree has its voice as well as its feature. At the passing of the breeze the fir-trees sob and moan no less distinctly than they rock; the holly whistles as it battles with itself; the ash hisses amid its quiverings; the beech rustles while its flat boughs rise and fall. And winter, which modifies the note of such trees as shed their leaves, does not destroy its individuality.

Hardy knew what many people living close to nature, especially the indigenous people, have always known. My friend the songwriter Dana Lyons told me how, after spending a few days under an ancient tree in an old-growth forest of the Pacific Northwest, he was suddenly filled with a song, which is called, simply, “The Tree.”

Shortly after this he was asked to play the song at a Native American powwow. At the end he said how it had seemed as though the tree had “given” him the song—music, words, and all. “Of course,” said the chief, and not only told Dana the species of tree but that he recognized the individual tree and told him its exact location. “We know all their voices,” said one of the elders.

Tuck is another good friend of mine who is familiar with tree voices. He works for the Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden in Hong Kong. There is a little bungalow hidden away in the forest that clothes the slopes of a mountain rising up above the polluted air of the city below. When I have time, I like to walk along the steep trails, to visit the hidden waterfalls and other secret places. It is open to the public in daylight hours, and many people come—to photograph the diversity of trees and plants, or just to breathe clean air for a few hours. But it closes at sunset.

After dark Tuck sometimes drives me around to look for porcupines, barking deer, wild boar, and the little leopard cat. The trees seem to acquire a new presence at night: they are stripped of color, and it is their shapes that one notices. Strange, gnarled, their branches reaching out over the road like arms.

During one such drive Tuck stopped the car beside a large tree whose roots were helping to hold the soil in place on the almost-perpendicular slope from which he grew.

“This old tree has something to say to you,” said Tuck.

I was not surprised by his remark, for I knew that he had attended seminars on listening to trees. When it was first proposed, he had thought the whole idea quite crazy, but he had gradually become a believer. He finds he can receive energy from certain trees when he stands near them and meditates.

We sat in the silence that followed the cutting of the engine. There was the call of an owl. After some moments of deep attention to that old tree, I seemed to feel or sense a message—a sort of thinking that urged patience, endurance. I should not expect that the world could change quickly. I should just carry on, do all I could, and never lose hope.

Perhaps I imagined it. Perhaps it was what I expected to hear from an old tree. But it left me with a tranquility of spirit, and I was grateful. It was not the tranquility that may come with fatalism. The old tree, most surely, was not suggesting we stop our efforts to prevent the felling of the forests, and the extinction of species. No, rather we must work harder, knowing it will take time, and never give up.