Chapter 4

Forests

There is a spiritual energy at the waterfall in Kakombe Valley at Gombe. This is where the chimpanzees sometimes perform their spectacular “waterfall displays,” swaying rhythmically from side to side, stamping and splashing in the water. It can also be a very peaceful place, and I sometimes sit here quietly for hours. (CREDIT: © JANE GOODALL INSTITUTE / CHASE PICKERING)

As a child, when I read the books about Tarzan, I was in love with the forest world in which he grew up as much as I was in love with the Lord of the Jungle himself. I was also entranced by the story of Mowgli in the Jungle Book, who was raised by wolves, and the descriptions of the mysterious Indian jungle where he lived with the other animals. I read about other habitats too, of course: the American prairies as they once were, stretching for countless miles over the wild central plains where the vast herds of bison roamed; the wetlands with their teeming bird life; the frozen Arctic home of polar bears.

In my imagination I traveled to them all, but it was the forests that I was most in love with. I read voraciously about the jungles of the Amazon Basin, India, Malaya, and Borneo. One book described the Amazonian jungle as a “Green Hell,” populated by ferocious wild beasts, snakes that were meters long, a whole array of deadly spiders and insects, fierce Indians, and, of course, rife with all manner of deadly diseases. But the very difficulty of getting to such places, and the dangers that would be encountered, appealed to my adventurous spirit. The fact that I could see no way of attaining my goal made me more determined than ever, despite the fact that people laughed at me.

I remember, vividly, a childhood visit to the Sherwood Forest, where Robin Hood and his merry men lived in the “greenwood,” robbing the rich to give money to the deserving poor. Much nearer home was the New Forest, a place of woods and bogs and wet heath and moors with heather. We went there a few times by train and walked and had picnics.

It was in Bournemouth, however, on the cliffs overlooking the English Channel and in the chines that led down to the seashore, that my real apprenticeship was served. There, with Rusty, I learned to crawl through dense undergrowth, scramble up sheer slopes, and creep silently along narrow trails. In sunshine and rain, heat and cold, those chines were my training ground where I developed the skills that were to stand me in such good stead in the forests of Gombe.

I learned the voices of the different birds—the haunting song of the robin, the sweet liquid notes of the blackbird, and the wild song of the mistle thrush (also known as the “storm cock”) as he sang from the very top of a tree when the wind was strong. I knew where many birds had their nests, and one spring I spent an hour most days watching, from behind a screen of bracken and brambles (Rusty lying motionless at my side), as a pair of willow warblers hatched and fledged their chicks. The squirrels gave me endless entertainment as they chased and challenged one another around and around a tree trunk, or sat hurling abuse down at me, their tails jerking with indignation. I loved the sunlight on the pink-gold trunks of the pine trees, and the sighing of the breeze through their leaf needles, and the eerie creaking when two big boughs rubbed against each other in the high wind.

When Dreams Came True

I cannot count the number of times that I have taken the boat from the little town of Kigoma and traveled the twelve miles or so along the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika to the tiny Gombe National Park. It is only thirty square miles as the crow flies, but if you ironed out the rugged terrain, it would be more than double the size. The beach that fringes the lake has been formed by the endless movement of the waters of the great lake into a series of bays between rocky headlands. The mountains rise up to the peaks of the Rift Escarpment—Lake Tanganyika is the flooded western branch of the Great Rift Valley.

The lower slopes along the shore are covered with deciduous woodlands intersected by narrow valleys supporting dense tangles of riverine forest that is almost impossible to move through unless one follows the trails used by bushbuck and bushpigs, baboons and chimpanzees. In the rich, fertile soil of the lower valleys, giant forest trees have found a foothold, and here, where the canopy overhead inhibits the undergrowth, it is possible to make use of our bipedal posture. The upper slopes, often very steep and treacherous, are covered by open woodland interspersed with stretches of grassland that become pale and brittle during dry season. Up high the trees are mostly small, save where the hills are bisected by the upper reaches of the valleys. Where the Rift Escarpment is highest, around five thousand feet, the trees are sometimes festooned with lichens that hang like beards from the branches.

These days my crazy travel schedule only allows me to get to Gombe’s forests twice a year, and only for a few days at a time, but one of those days is always set aside for me to be quite alone in the forest, and it is those precious hours that, more than anything else, replenish my energy.

I love to sit by the small, fast-flowing streams and listen to the sound of their gurgling as they tumble past on their way to the lake. Or to lie on my back and gaze up at the canopy, where little specks of captured sky twinkle like stars as the wind stirs the branches and leaves high overhead. I become deeply aware of the voices of the forest—the soft rustling of small creatures going about their business, the buzzing and whirring of insect flight, the shrilling of the cicadas, the calls of birds, the distant bark of a male baboon—and all the other sounds that are as familiar to the forest dweller as the squealing of tires skidding around a corner, the revving of engines, and the drunken shoutings are to those who live in the city. And there are those times when it is raining and I can sit and listen to the pattering of the drops on the leaves and feel utterly enclosed in a dim, twilight world of greens and browns and soft-gray air.

When I am alone and quiet and still, animals will sometimes come very close, especially birds and squirrels feeding in the trees. Very rarely I have been able to watch a checkered “sengi,” or elephant shrew (which is not a shrew at all), hunting insects on the forest floor. It has a long snout and squirrel-like body and is very shy. I have never seen one except in thick undergrowth, given away by the rustling of dead leaves. Every so often it slaps the ground with its ratlike tail—I cannot find reference to this, but I wonder if it startles insects so that the sengi can more easily detect them.

Life and Death in a Forest

During all my years in Gombe, I came to realize, in the most vivid way, that the forest is a living, breathing entity of intertwining, interdependent life-forms. It is perfect, complete, a powerful presence, so much more—so very much more—than the sum of its parts. One comes to understand the inevitability of the ancient cycles, life gradually giving place to death, and death in turn leading to new life. It is illustrated every time a tree falls. I was once caught in a sudden and violent thunderstorm during the rainy season. Huge tree trunks bowed before the force of the wind as whole branches were torn off. And I actually witnessed the event as one of them, a species of fig, lost its grip on the rain-softened earth of the forest floor and, with a great rending sound, crashed to the ground. I can never forget that experience, for I was almost crushed by one of the outstretched limbs.

Over the following years I went to visit that tree each time I returned to Gombe. It was not long before the first mosses and lichens and fungi appeared, growing on the fallen trunk. And then came the ferns and small flowering plants. Later, young seedlings sprouted close by, growing up from fruits that had been produced before the tree’s death, making the most of the sunlight that shone down through the recently created gap in the canopy. One or more of them would take the place of their decaying parent. Not surprising that these fallen trees are known as “nurse trees.”

Year after year, the variety of life around my fallen tree increased, as more and more plant species appeared, as well as all manner of invertebrates. Small mammals made their homes there. And eventually it was difficult to see that it had ever been, so perfectly had it dissolved into the forest floor—“ashes to ashes, dust to dust”—where the “ashes” and “dust” were the rich loam that helped to ensure the future of the forest.

It was to the forest that I went after my second husband, Derek, lost his painful fight with cancer in 1981. I knew that I would be calmed and find a way to cope with grief, for it is in the forest that I sense most strongly a spiritual power greater than myself. A power in which I and the forest and the creatures who make their home there “live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). The sorrows and problems of life take their proper place in the grand scheme of things. Indeed, with reality suspended by the timelessness of the forest world, I gradually came to terms with my loss and discovered that “peace that passes all understanding” (Isaiah 26:3). And I knew my task was to go on fighting to save the places and animals that Derek and I had both loved.

As I travel around the world, people are always telling me that I have an aura of peace—even when I am surrounded by chaos, by people jostling for signatures, or wanting to ask questions, or worrying about logistics. “How can you seem so peaceful?” they ask. The answer, I think, is that the peace of the forest has become part of my being. Indeed, if I close my eyes, I can sometimes transform the noise of loud talking or traffic in the street into the shouting of baboons or chimpanzees, the roaring of the wind through the branches or of the waves crashing onto the shore. That I have this power is a gift that I have taken from the forest, for which I am deeply, endlessly grateful, for it helps me to survive the hectic pace of my endless lecture tours.

Forest Challenges

How amazingly fortunate I was that Louis Leakey picked Gombe as my study site—working there, beside the shores of a great lake, with its fast-running, clear, sweet streams and scarcity of dangerous animals, is as close to paradise as it gets. Life is not so easy for many of those who choose to do their research in a tropical forest. Indeed, working in some forests can be challenging for a human from the Western world.

Even in Gombe it is not all plain sailing. There are some trees that can give you a painful surprise until you get to know them and the vicious thorns they grow in unexpected places—on branches and trunks. And there is that little plant with stinging hairs that I have already mentioned—but if you watch where you are sitting, you are fine. There are some biting and stinging insects, but Gombe has far fewer than in many other forests. Probably the nastiest of these are the army, or driver, ants that march through the undergrowth in wide columns, fanning out if disturbed. Their bite is extremely painful—and once they get a grip, they hang on like little bulldogs and must be pulled off. The worst thing about these ants is that they have the sneaky habit of moving undetected up your legs and then, in response to some secret signal, all biting at once—but only when the leaders have got high enough to do real damage!

Of course, the Gombe terrain is rugged, so that, when working in the forest, you spend most of the day climbing up and down steep slopes, often having to crawl—or even wriggle on your tummy—through very dense undergrowth. But that is a small price to pay for the fact that you can lie on your back on the forest floor to watch chimpanzees or monkeys or birds in the canopy above. Other field researchers are less fortunate.

Dian Fossey persuaded Louis Leakey to help her fulfill her passion—to go and study the mountain gorilla in Rwanda. She endured far greater hardships than I. She had to wear several layers of clothes to protect her from the giant stinging nettles, and endure days and days of mist, pouring rain, and deadly chill. Everywhere was the danger of bumping into forest elephants and buffalo—one of her research assistants (Dr. Sandy Harcourt) was really badly gored by a buffalo during his time at her research station. And she had terrifying encounters with poachers.

Birute Galdikas was the third of “Leakey’s angels,” as we were sometimes called. Unlike Dian and me, she already had a degree in anthropology when she first approached Louis, begging him to help her fulfill her dream—to study the orangutan, the “red ape.” I think her study site in Indonesia provided the toughest challenges of all. We have often talked about the many difficulties she had to overcome in the forest of Kalimantan. One time she sat on a fallen tree trunk and received second-degree acid burns—through her tough trousers. And, she said, there were ants—vicious, biting, stinging ants—everywhere. Worst of all were the thousands of leeches waiting to attach themselves to her as she walked through the moist undergrowth. And her encounters with the perpetrators of the illegal logging were scary—once she was seized and badly beaten up.

A World of Unique Forests

There are so many different kinds of forests—tropical, temperate, boreal, montane, and cloud forests—and within each category, many different types. There are the riverine forests, belts of dark green that snake across the country, following the rivers, such as those I have known in Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi. In these forests, as mentioned, the undergrowth tends to be dense and tangled, making it difficult for us bipedal apes to move about.

Then there are those that I call the “secret forests,” in the western coastal area of Congo-Brazzaville: one moment you are walking across a flat floodplain with its tall grass and stunted trees, and then suddenly you come to the edge of a very steep, narrow gorge. At the bottom, tall trees grow, their canopies barely showing above the gorge, and when you climb down, you are in a completely different atmosphere, cool and dim after the burning sun.

And there are the great forests of the Congo Basin, the Amazon, and the wild forests of Asia, some still unexplored, that are home to such a staggering variety of different species of plants and animals, all forming part of the intricate web of life. If we want to sound knowledgeable, we say that they are “biodiversity hot spots”—it means the same thing. Because the canopy is high and dense, much of the forest floor is deprived of light, the undergrowth is sparse, and often one can walk upright, especially when following elephant “highways.”

I have been lucky enough to experience life in the treetops from three different canopy walkways—in Panama, in Ghana, and in a dry forest in America. It is a whole new world up there, populated by countless creatures that know no other existence and that come into being, live, and die in the treetops. It is a world created by those plants that have succeeded in their desperate struggle to escape from the eternal gloom of the forest floor and have reached the life-giving sunlight high above.

It was from Margaret Lowman, best known as “Canopy Meg,” that I learned about this world. She pioneered the study of life high up in the trees, experimenting on the different ways of getting up there. And it was she who told me of the difficulties that must be overcome by every tree that makes it. How incredible to realize that what looks like a “seedling” because it is only four inches high may, in fact, be fifty years old! Hoping to avoid being trampled or eaten, it is patiently waiting for a big tree to fall and create a gap in the canopy, thereby letting some sunlight fall to the ground. Only then can it start to grow up toward the sky. Research in the canopies around the globe, conducted by “Canopy Meg” and her colleagues, has shown that almost half of the world’s biodiversity is found up there in the tops of trees—for many species it is the only habitat they know.

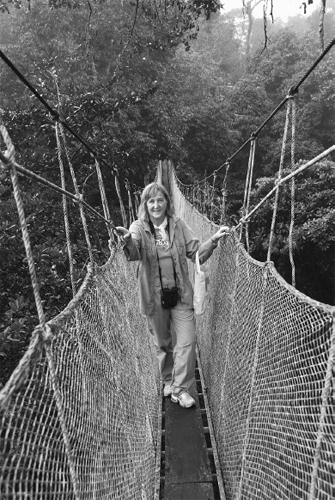

“Canopy Meg,” Margaret Lowman, pioneered the exploration of the forest canopy. Her writings have taught us about a new and previously undreamed-of world, high above the ground, where almost half of the world’s biodiversity is found. (CREDIT: MEG LOWMAN)

Africa’s Last Eden

I have vivid memories of the various forests around the world that I have been privileged to visit, but of all my forest experiences, outside Gombe, one was particularly exciting, wonderful—and awe-inspiring. That was when I visited the Goualougo Triangle in the Republic of the Congo, a forest that, for thousands of years, was totally protected from human interference. I was invited on this memorable expedition by the scientist, explorer, and conservationist Dr. Mike Fay. Mike discovered the hidden forest, which became known as the “Last Eden,” in 1999 when he undertook a marathon eighteen-month walk across Africa to explore the virtually unknown forests spanning the countries of Congo and Gabon. His two-thousand-mile route was mapped out very precisely before he began the expedition, and in the Republic of the Congo it took him straight through a series of great swamps that encircled—and protected—one hundred square miles of ancient, pristine rain forest. Even the indigenous Pygmies had not ventured through those swamps.

Mike was accompanied on much of his trek by my old friend, photographer Mike “Nick” Nichols. Together they struggled through the swamps, coped with insects, leeches, and other parasites, and survived sometimes-terrifying encounters with suspicious and angry elephants and gorillas. These and the other animals had not learned to fear Man—but that did not mean they always welcomed the intrusion of the strange creatures that they had never seen before. The illustrated story of the “Last Place on Earth,” with Nick’s fabulous photography, is published by the National Geographic Society.

Since Mike first pioneered the way, an established route has been worked out, and a few lucky people have been privileged to visit. I was one of them. A National Geographic film team, along with writer David Quammen, accompanied Mike, Nick, and me. We flew from Brazzaville in a small plane, landing and spending the night in a field station that had been built for loggers. We left very early the next morning, and as we drove through the old, regenerating logging concession, we could watch the black nighttime silhouette of the branches against the sky gradually acquire depth and color as the sun rose.

After three quarters of an hour or so we arrived at the swamps, not far from a small settlement of Pygmies. Some of them, who would act as our porters, were waiting for us with their canoes. The little boats, propelled forward by powerful thrusts of long poles, glided swiftly and silently through a maze of channels in the bright-green vegetation. There were all manner of birds, including flocks of African gray parrots with their loud, penetrating voices and arrow-swift flight. I was overjoyed to see these highly intelligent animals, so often imprisoned in tiny cages, free in the wild.

Once we had crossed the swamps, it was walking—for me, and for the TV crew with heavy equipment, it seemed a long, long way. The Pygmies with our camping gear went on ahead, women carrying similar loads to the men—as they insisted.

We stopped once for about an hour to watch a group of gorillas emerge from the forest, walk carefully across the bright-green grass of a water meadow, then sit waist-deep in water feeding on great handfuls of waterweed. After that interlude we followed elephant trails for miles beneath the towering and ancient trees. Many kinds of monkeys called down to us as they leapt through the branches high above, and always we were surrounded by bird life. Tiny, stingless bees buzzed so thickly around our heads every time we paused, crawling into eyes and ears—and mouths if they could—that I was glad to wear a hat with mosquito netting hanging down from the brim.

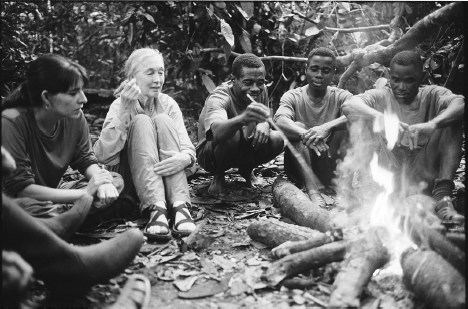

Sharing stories around the campfire during my magical days in the “Last Eden”—the forest of the Goualougo Triangle in the Republic of the Congo. I am talking with chimpanzee researcher Crickette Sanz and a group of indigenous Pygmies, one of whom is demonstrating how the chimpanzees from this forest use tools to feed on termites. (CREDIT: MICHAEL NICHOLS / NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC)

Night had fallen and I was utterly exhausted, with blistered feet, when we finally reached the camp of the two scientists studying chimpanzees there, Dave Morgan and Crickette Sanz. For three days they introduced me to their study site. Their work was not easy, for the chimpanzees were mostly really high in the trees, silhouetted against the sky—and standing peering up through binoculars is neck-breaking, backbreaking work. At Gombe I would have lain flat on my back to watch them—but in that forest I was warned against this because of the small insects that can bite through your clothes and lay eggs under your skin. Later these hatch, producing little bumps that itch and hurt horribly as the developing larvae wriggle about inside, feeding on your flesh. We all carried a little square of tough plastic to sit on, but later I discovered that two had managed to get into my bottom!

As well as the chimpanzees, there are many troops of lowland gorillas in the area, and sometimes as we walked through the forest, we would hear a crashing of branches and the chest thump and heart-stopping roar of a male gorilla protecting his females, just out of sight in the undergrowth. Once Dave Morgan had been severely attacked by a male gorilla and was lucky to have survived. The gorilla had been upset by something—Dave had heard his angry screams before he saw him. It had been a terrifying incident, and I marveled at Dave’s courage in continuing his work in the forest—even though that gorilla was far from the study site.

The three days I spent there were among the most memorable of all my forest experiences. I was introduced to some of the individual chimpanzees Crickette and Dave had come to know, and learned about their behavior as we sat around the campfire in the evening. Once, we were joined by three of the Pygmy trackers, and I was fascinated to hear their stories of chimpanzees, especially when they talked about tool using. These men sometimes imitate the call of a duiker as a way of attracting any chimps in the area, for this little antelope is a favorite prey.

And after supper I would lie in my tiny tent, listening to the night sounds of leaves in the wind, and the calls of insects and owls. It was especially wonderful to know that the sound of a chainsaw or ax had never reached this forest, nor had any creature been shot with a gun or arrow.

Mike had organized the whole expedition so that he could introduce me to this magical place—he knew the effect it would have on me, and that I would be an even better advocate for the protection of the rain forest as a result. Once, as we walked through the forest, he stopped to draw my attention to a particularly magnificent tree, towering up and up, its crown lost in the canopy far above.

“It must be at least a thousand years old,” he said, gazing up into its branches high above us.

I walked over and laid my hand on the massive trunk of this majestic and venerable individual, sensing its ancient life force. And I thought of the millions of trees, just as old, just as magnificent, that we have cut down and killed over the ages. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine the sound of a chainsaw, the harsh shouting of men, the shuddering, the creaking and groaning, of the assaulted tree. I tried to imagine the horrifying crash it would make as it fell, the harm that would be inflicted on the other trees in its path, and the terror of the countless creatures who had made their homes in its trunk and branches.

And as I visualized the death of that sacred living being who, over hundreds of years, had quietly grown from the forest floor where I stood looking up toward the sky, there were tears in my eyes. Mike must have been thinking similar thoughts, for suddenly he interrupted my musings. “If the trunk of a tree like this is cracked as it falls, then the loggers will just leave it lying in the forest,” he said. “And at least half of any large tree is wasted anyway—they only take out the most valuable part of the trunk.”

My tears gave way to anger. Someone once wondered why it is that if a work of Man is destroyed, it is called vandalism, but if a work of nature, of God, is destroyed it is so often called progress.

The terrifying destruction of the world’s forests is one of the greatest ecological disasters of our time. The reason that I left my Gombe paradise to take up my life on the road was that I realized, during a conference in 1986, the speed with which the African forests were disappearing and the shocking decline in the numbers of chimpanzees and gorillas and other wildlife across the continent. Foreign timber companies were operating in the forests of West and Central Africa. Roads to previously inaccessible areas were opening up the forests for the bushmeat trade. Human populations everywhere were expanding, taking more and more land for growing crops and grazing livestock.

Today, a quarter of a century after that conference, the onslaught on the forests continues. It is not only an environmental tragedy but a crime against Mother Nature, and it affects me in the depths of my being. Time was when our ancestors lived in the forest, and I feel an instinctive, primal need to walk among the trees. It is desperately important to influence policymakers and corporate leaders, now more than ever before. The ongoing carnage in our forests is terrifying in its scope—there is not much time left.

Fortunately there are dedicated and passionate people who are fighting desperately to save our last forests, and I shall talk about them and their brave campaigns in a later chapter.