Chapter 8

Orchids

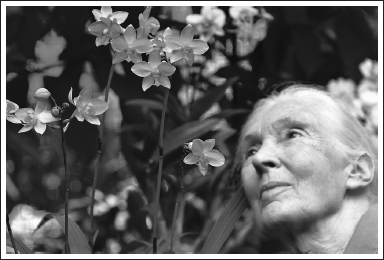

When I look at this orchid, I feel a sense of awe. So beautiful, and with my name attached: Spathoglottis Jane Goodall. I love to see it growing in the Singapore Botanic Garden among all the other glorious flowers. (CREDIT: BENG CHIAK TAN)

With their fantastic designs, colors, and sizes, orchids have bewitched us from earliest times. People have lost their lives searching for them in wild and remote parts of the world. Whole industries have grown up around propagating, hybridizing, and selling them. Countless books have been written about them, many illustrated lavishly with superb photographs and paintings. In one of these, About Orchids, A Chat, published at the end of the nineteenth century, one Frederick Boyle wrote, “the majority of people, even among those who love their garden, regard them as fantastic and mysterious creations, designed, to all seeming, for the greater glory of pedants and millionaires.”

Designer flowers, by God, for the elite! But although we can smile—or sneer—at Boyle’s supreme arrogance, I have to admit that I always felt there was something artificial and opulent about orchids. Those that I knew when growing up were hothouse orchids. I only saw them in the houses of the wealthy—the kinds of orchids that are, today, an essential part of the decor (sitting rooms and—the indignity of it—bathrooms) in all upmarket hotels.

In the warm tropical air of the National Orchid Garden in the Singapore Botanic Gardens, countless species grow in a more natural setting. I walked around among the trees and rocks where they grow, and in the late-afternoon sun they had an almost mystical beauty. There was one small grove where every orchid had a delicate fragrance. Nearby was an area where hybrid orchids grow, each developed to honor a particular individual. How wonderful to see the orchid named for me—Spathoglottis Jane Goodall. Most of the others have been named for members of royal families, presidents, ministers, well-known movie stars, and so on. And now me!

Once I started thinking about these fascinating plants, I decided they needed their own chapter. They make up 8 to 10 percent of all plants. They grow wild in almost every country, colonizing just about every ecological niche—in fact, they are only absent from true desert and frozen ice fields.

I have always thought of orchids as tropical plants and was amazed to discover that about thirteen species are found north of the Arctic Circle—more than in Hawaii, where there are only three! Some orchids are terrestrial, although most grow on rocks or up in trees. A species of orchid is often quite restricted in its range, with many being found on one mountaintop only or in one small forest.

With a height of only one-tenth of an inch, Bulbophyllum minutissimum is considered the smallest orchid on the planet. By contrast, the vanillas have vines reported to reach higher than sixty-five feet, making them the tallest of all the orchids. In some species of vanilla the leaves have almost vanished, appearing like little scales on the green stem. And the tiny and rare British ghost orchid (Epipogium aphyllum) has no leaves at all, and its food is manufactured by fungus on its roots. It spends most of its life underground, and only emerges on a small pale stem to flower, in the darkest part of the wood, when conditions are just right.

Another little orchid, Bulbophyllum nocturnum, discovered by Dutch botanist Ed de Vogel in 2008, on the Island of New Britain in Papua New Guinea, is the first true night-blooming species known. Its flowers open at ten p.m. and close at dawn—and they bloom only once. My Dutch botanist friend Rogier van Vugt, from Leiden University, tells me their scent is similar to blue-veined cheese and probably attracts fungus gnats. Only one individual was found—on a logged tree. It was the last known specimen in the world and it may well be extinct in the wild, as most of the area has now been logged. Fortunately Rogier managed to self-pollinate the specimen and obtained seeds so that the plant “now has numerous seedlings and is no longer alone.”

Orchids are usually pollinated by insects, and for most only one particular species of insect can do the job. Typically one of an orchid’s petals is shaped to serve as a “landing pad” for the desired pollinator. The visitor is attracted in several ways—the most successful species (those that produce the most seedpods) offer nectar as a reward.

And then there are the cheats. Their flowers mimic, for example, the female of their specific insect pollinator: when the male tries to mate with this fake female, he unknowingly enhances the orchid’s reproductive success—but not his own! The best known of these cheats is the bee orchid—the flower looks and feels like a female bee and even has the same pheromones. I hope, for the bee’s sake, that he has an enjoyable, though futile, experience.

This extraordinary and fascinating behavior naturally intrigued Charles Darwin, who wrote in a letter to Sir Joseph Hooker of Kew, “I was never more interested in any subject in my life, than in this of orchids.” He published a book in 1877 called The Various Contrivances by Which Orchids Are Fertilised by Insects.

Once fertilization has been achieved, the orchid produces an incredible number of seeds—as many as four million. I wonder who had the job of counting them!

All in all, we can agree that orchids have a fascinating sex life.

Prince of Orchid Hunters

Many people have developed an almost obsessive fascination for orchids, so it is hardly surprising that a number of the dedicated, crazy plant hunters of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries set off on expeditions into unmapped, unhealthy, and often dangerous tropical climes in search of new species. The jungles of Central and South America yielded particularly exotic blooms.

The orchid frenzy that seized Europe, though not quite as extreme as the earlier tulip frenzy, nevertheless saw collections and individual plants auctioned off for enormous prices. The plant hunters competed with one another, and jealously kept secret new sources of especially exotic species—even going to the extent of providing others with false maps. Many of these men accomplished extraordinary feats of endurance—and a number died. One of them searched the whole length of the Amazon River from source to ocean, and in addition crossed the Andes numerous times, climbing to heights of up to nineteen thousand feet. Another hunter traveled the same river the other way around, from sea to source.

One man stands out—the Czech Benedikt Roezl, who has been referred to as the Prince of Orchid Hunters. He had a flair for discovering new and rare species—not only of orchids, incidentally, but of many other beautiful flowers as well—in Latin America and other parts of the world. On one occasion, in 1871, after an unsuccessful trip, he was traveling back by canoe with one native helper. The river was swollen with recent floodwater and was flowing fast. All manner of debris was being swept along, surely posing some danger to their fragile craft. Suddenly Roezl saw that a large uprooted tree that was about to pass them was festooned with many kinds of epiphytes, ferns, and mosses. Quickly paddling toward it, they tied their canoe alongside and gathered up the unexpected and amazingly rich bounty of plant life.

Roezl, unlike many of the orchid hunters who perished of disease, wild animals, natives, bandits, or accidents of travel, survived to die peacefully in his own home back in Prague. This is not to say that he did not have his fair share of adventure—he was, for example, robbed seventeen times. Unlike others of his time, he traveled light, in the manner of many of the famous plant hunters of the previous century. And it was this fact that, on one occasion, almost led to his death, for the Mexican bandits who had captured him were angry that he had so little to steal and they had their knives out ready to kill him. He was only saved, at the last minute, when one of their number pointed out that it was unlucky to kill a madman, and clearly this man who traveled with little but stacks of “weeds” must be crazy. They put away their knives and allowed him to carry on with his journey.

Stolen for Beauty

“For when a man falls in love with orchids,” writes Norman MacDonald in The Orchid Hunters: A Jungle Adventure, “he’ll do anything to possess the one he wants. It’s like chasing a green-eyed woman or taking cocaine, it’s a sort of madness.”

This madness, this desperate quest by so many people for more and yet more new and exotic orchids, unfortunately led to the felling of thousands of forest trees for the epiphytic orchids that grew on them. And because so many of those species are highly endemic, with all individuals of one species being found in a tiny area, the felling of even one of their habitat trees may compromise the gene pool of the whole population. In extreme cases every individual orchid has been removed from its habitat.

Tragically the same greed continues today. Even though in most countries it is illegal to collect orchids without a license that limits the applicant to a strict quota, thousands of plants are collected illegally. Often this is so that new hybrids can be created, propagated, and sold. Dealing in orchids is the most lucrative flower business worldwide, involving some $44 billion per year in legal business, in addition to what is garnered through illegal dealings.

Nothing illustrates the madness that seizes orchid people more than the series of events that followed the discovery, in 2002, of Phragmipedium kovachii. It is a stunningly beautiful orchid from the Amazon rain forest in northeast Peru, with a blue-purple flower that can have a horizontal spread of up to nine and a half inches. This discovery led to a series of international scandals and intrigues that inspired Craig Pittman’s recently published book The Scent of Scandal: Greed, Betrayal, and the World’s Most Beautiful Orchid.

The story began when Michael Kovach, an American orchid collector, stopped at a roadside kiosk in Peru that sold orchids. The vendor, Faustino Medina Bautista, offered him three fantastic orchids. Kovach had never seen anything like them and was sure they were a new species—perhaps his dream would come true and he would get an orchid named for him.

He flew with one of the plants, concealed among other less exotic specimens, to the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens in Sarasota, Florida, famous for its collection of more than six thousand living orchids. When he walked in with his glorious bloom, there was a gasp of astonishment.

Kovach, of course, should have had an export permit. But this could only have been issued if the orchid was being cultivated in Peru, and it would have needed a name—which can only be given when a detailed description has been published. Therefore, it is not easy, legally, to take a new species from its country of origin.

Unfortunately for the Selby Botanical Gardens, there were others who already knew about Kovach’s orchid, since vendor Bautista had been selling them (for less than a dollar apiece) before Kovach turned up there. And a former Selby employee and local orchid taxonomist, Eric Christenson, had obtained a photo from Peruvian scientists, and was working to describe it himself. He planned to name it P. peruvianum in honor of its homeland. When Selby’s taxonomists heard about this rival effort, they started working around the clock, and managed to get their description published in their own scientific journal just five days ahead of Christenson’s.

There was excitement and celebration at Selby. They had described an orchid that was the discovery of the century. And Kovach was ecstatic, for this orchid was named for him. But the euphoria was short-lived. Eight days after the published description federal agents, possibly tipped off by Christenson, began investigating the whole situation. Kovach, Selby, and some of its board were found guilty, fined, and put on probation.

At the same time, this orchid was becoming one of the most coveted in the world. Offers to buy it on the black market reached as high as ten thousand dollars, and orchid fanatics everywhere were prepared to bend rules and break laws in their obsessive quest to possess it.

And what of the situation in the wild? By 2003 the site where Kovach’s three orchids had originated the year before was cleaned out. Another site was found with more than a thousand plants, but a few weeks later, when an enthusiast went to photograph them, he found just two orchids remaining, high on a rocky ledge. By an odd coincidence, when he got back to his hotel, he saw a pickup truck loaded with seven large rice and coffee sacks, stuffed into which were several hundred of the largest orchids he had ever seen, their leaves some three feet long. They were the last of the plants (except for the two that had escaped) he had just been hoping to visit in the wild.

No attempt had been made to conceal the stolen orchids, and he was able to track down the name of the thief. He reported him to the Peruvian wildlife authority—but no action was taken. Since then three other sites have been found, two of which have already been plundered.

Five years after discovery, P. kovachii orchids were finally being cultivated in Peru: but only three nurseries had been issued permits to collect legally, and they were allowed to take only five orchids each. Yet during those same five years tens of thousands were taken illegally from the wild, few of which will have survived. I can understand why serious collectors tend to defy government restrictions.

A Clever Rescue Strategy

One way to protect an endangered wild orchid from the avarice of the collector is to flood the market with captive-bred individuals. This strategy was certainly successful in the case of the Sulawesi “rotting meat” orchid (Bulbophyllum echinolabium), which, until recently, was threatened by both overcollection and logging.

I heard the story from Rogier, my botanist friend from Leiden University. “This orchid is certainly not pretty,” he said, “but it has a charm that is exotic—or, better said, bizarre.” It consists of a cluster of swollen green bulb-like stalks, the younger ones carrying hard, succulent leaves. It may have one or several flower spikes, each of which has just one bloom at a time.

“Each flower,” says Rogier, “is an impressive piece of natural art, measuring some thirty centimeters (almost twelve inches) from tip to tip with long, thin pinkish-green petals and an odd, spiny red lip that is connected to the rest of the flower by a hinge-like system.” This is what gives the plant its name—echinolabium means “spiny lip.”

This orchid, as its name implies, is one of those unusual plants that attract pollinators by smelling like rotting meat. When a fly creeps to the center of the flower, the hinge closes, pressing the insect against sticky pollen grains. In a few moments it is released, after which, with luck, it will visit another stinking flower and deposit pollen on its stigma.

For a while the rotting-meat orchid, which has a very small range, was believed to be extinct in the wild. However, biologist and enthusiast Simon Wellinga, who has many species of orchid growing at his home in the Netherlands, had two Bulbophyllum echinolabium. He was propagating them using a method that is now well established—collecting the seeds, sterilizing them, and sowing them on a sterile jellylike substance that contains the nutrients the germinating orchid would get from the mycorrhizal fungi in the wild.

When Simon learned how rare his two plants were, he cross-pollinated them to produce a seedpod containing hundreds of thousands of seeds. He successfully grew thousands of young plants, which he shared, free of charge, with nurseries around Europe. He sent the bulk of the seeds to a seed bank in America so that orchid fanciers there soon had the opportunity to grow them as well.

A few years later a very small population of these orchids was rediscovered in the wild. Thanks to Simon and others who have now grown the species on a large scale, the desire to collect from the field is nonexistent, and the newly found wild individuals will at least be safe from poaching.

Orchids as Medicine and Food

It is not only for their beauty that orchids are valued but also for their medicinal properties and as food. The first records of orchid medicinal use date back three thousand years, when the Chinese were using them for a variety of ailments, especially sexual problems. And throughout recorded history, in many parts of the world, a whole variety of orchids were—and still are—believed to have aphrodisiac properties. If you wonder why, just take a look at the tuber of an orchid of the Orchis genus. The name of the plant is derived from the Latin word orchis, which means “testicle.” The toxicologist Paracelsus, referring to one of these tubers, wrote, “Behold the Satyrion root, is it not formed like the male’s privy parts? Accordingly, magic discovered it and revealed that it can restore a man’s virility and passion.” Still today, in various parts of the world, certain orchids are used to treat a whole variety of sexual disorders, from impotence and poor performance to infertility.

In Turkey, where the orchid’s supposed aphrodisiac qualities have long been appreciated, they are also used in cultural cuisine. The tubers are dried and ground up to create a kind of starchy flour, known as satyrion, which is used to make a traditional drink—known as “salep.” It became popular in England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, where it was known as “saloop.” With the advent of the coffee and tea shops the demand for saloop diminished, but for quite some time it was still offered as an alternative to coffee. Sometimes the British used their own native orchids to make the drink—in this culinary context they were known as “dog stones,” which was simply slang for “testicles.”

When you look at the tuber of an orchid, it is easy to see why its name comes from the Latin word orchis, meaning “testicle.” (CREDIT: ROGIER VAN VUGT)

Recently salep has become increasingly popular outside Turkey, and huge numbers of the tubers are exported. As a result, these orchids face extinction, although projects are now under way that employ local people to protect wild orchids, and efforts are being made to cultivate them commercially.

In Africa, too, biologists and conservationists are stepping up efforts to protect some of the continent’s rich diversity of orchids, many of which—more than seven hundred have been listed—have long been valued as medicinal plants and food for humans and livestock. During one of my last visits to Tanzania I heard about one relatively new threat to some of the country’s orchids.

The problem originated in neighboring Zambia, where, until the early 2000s, orchid tubers were considered a “famine food.” But things began to change: boiled tubers became a fashionable dish in urban areas and led to what has been referred to as an “orchid rush.” As a result of this escalating demand, several species of the genera Disa, Habenaria, and Satyrium are now endangered. Another, the leopard orchid, is valued for various medicinal reasons—especially to help with cough and rheumatism.

The growing shortage of these orchids in Zambia triggered a huge and quite unsustainable illegal trade across the border from Tanzania—in recent years it has been estimated that a staggering four million are smuggled out each year. In an effort to protect at least some of their orchids, the Tanzanian authorities have made a new and beautiful national park on the Kitulo Plateau—the local people call it Bustani ya Mungu, “The Garden of God.” This 159-square-mile area is rich in plant diversity—there are forty-five species of orchid alone.

And I was happy to hear that efforts are being made not only to protect some of the food-giving orchids in the wild but also to try to grow them commercially—as was the case with the vanilla orchid (Vanilla planifolia), which is the source of vanilla flavoring.

The Secrets of Orchid Farming

Vanilla planifolia, like all members of the vanilla genus (more than one hundred have been described), is a vine, and in its homeland of Mexico and Central America it climbs trees in the forest to heights of up to 35 meters (almost 115 feet). Its cream-colored flowers, each blooming for only one day, exude a sweet scent, probably to attract its pollinator, the Melipona bee. It is the elongated, fleshy seedpod that provides us with vanilla.

When the pod is ripe, it becomes dark brown or blackish and gives off a powerful scent. It is best to pick the pods just as they start to split open. Traditionally they are then laid out in the sun for a couple of hours each day and wrapped in blankets to “sweat” overnight. After two or three weeks of this treatment, they start to produce the powerful vanilla scent, and then they are dried for a further two to four weeks.

Although the Totonac people of Veracruz, Mexico, may have been the first to gather vanilla from beans found in the forest, it seems that it was other pre-Columbian tribes in southern Mexico and Central America who learned to cultivate the vines. When they were conquered by the Aztecs in 1427, they paid their taxes with vanilla pods. Eventually this led to the Aztec rulers developing a fondness for the scent as well as the taste of vanilla. They even began using it as a flavoring for their cacahuatl, a popular water-based drink made from cacao beans and honey. And they added it to their medicinal remedies (such as those for treating headaches and indigestion and even more serious conditions, like animal bites and poisoning) to make the medicine taste better.

In 1519, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés sent vanilla beans, along with cacao beans, from the capital of the Aztec empire back to Europe. There’s little evidence that the Europeans valued the Aztecs’ vanilla beans as medicine, but they were delighted to discover a new and exotic aphrodisiac. To this day, vanilla is still a popular ingredient in perfumes and aromatherapy products, precisely because so many people find the scent and the taste vitalizing and erotic.

European cultivation of the orchid did not occur until 1836, when the Belgian horticulturalist Charles Morren realized the connection between the Melipona bee and the vanilla flower in its original habitat. Prior to this, those trying to grow the orchid, although they understood the climate that was needed, had not realized that an insect was necessary for pollination. Morren developed a method for hand-pollination, but it was time-consuming and costly.

It was twelve-year-old Edmond Albius, whose mother had worked on a vanilla plantation on Réunion (a small island off Madagascar), who revolutionized vanilla farming. The young Albius came up with a unique and innovative method of hand-pollination that is still being used to this day.

Orchids in Peril

The biggest threat to most orchid species is the destruction of their habitat. Thousands of species live in rain forest trees and are often driven close to extinction, or even over the brink, as a result of the felling of tropical forests for timber or farmland. Without doubt many endemic species—which may live in one small area only, such as one mountain—become extinct before they are discovered and described.

Orchids are not only threatened in the tropics. It is the same all over the globe, wherever we humans have moved in with our growing numbers, our hoes and spades, bulldozers and chainsaws, roads and developments. In addition to which, since most orchids rely on insects for fertilization, our use of pesticides has wreaked havoc. And now there is climate change.

Fortunately there are very many orchid enthusiasts working to save them, protecting them in their natural habitat, and seeking to propagate them in captivity. I met one of them during a recent visit to Australia and was delighted by his enthusiasm. Paul Scannell, from the Albury Botanic Gardens in New South Wales, is particularly passionate about one species of very beautiful and very endangered orchid, the crimson spider orchid (Caladenia concolor). In his area of the box woodlands there are just eighteen individual plants: they would not be there but for Paul.

“It’s a fragile environment,” he told me, “badly degraded as a result of land clearing, trail bikes, and four-wheel drives, deliberately lit fires, firewood and bush rock collecting, cattle breaking through fences, predation by native animals—and years of drought.”

It is the involvement of the local people, including the Aboriginal Wiradjuri community, that is saving this orchid. As soon as Paul alerted them to what was going on, they began raising money and building fences around the habitat. The scientists, meanwhile, were working out a recovery plan. “But if we had waited for that,” Paul told me, “the orchid would probably be extinct by now.”

Paul organizes surveys during which volunteers check on known plants and search for new ones. They note where new fences must be constructed and old ones repaired to keep the orchids and their habitat safe from livestock and vehicles. It is hard work, and it is ongoing, for at any moment some new threat may confront the team.

But orchid people will never give up. I had a letter from Paul a few months ago. “Our beautiful crimson spider orchids, with their intricate and complicated lives,” he wrote, “have survived everything nature has thrown at them over the ages. The eighteen plants in our local population have continued to defy the odds and remain static in their numbers.”

Hopefully a way to increase those numbers will soon be found: many orchids can now be propagated in botanical gardens, by horticulturists. All around the world they are doing well in captivity, and already, where the habitat is suitable, some have been reintroduced into the wild. And there are plans to reintroduce many more.

Saved by a Stapler

My Dutch botanist friend Rogier told me a quite marvelous story about a friend of his, Tom Velardi, who is saving orchids in his own, very special way. When Tom tired of his hectic life in the United States, he set off for Japan with nothing but one suitcase and some books and became an English teacher in the city of Fukuoka. Tom, a nature lover, delights in the native flora of Japan and loves to photograph the plants while hiking in the mountains.

There are a few species of very small epiphytic orchids in the forests there, but they are rarely seen, as they often grow high up in the trees. In the stormy season, however, many branches break off and end up on the forest floor. And that is when Tom sometimes finds tiny orchids growing on them. Knowing that these plants need fresh air and light to grow and are sure to die if he leaves them on a fallen branch, Tom collects the plants and nurtures them at home. Then, when the storms are over, he returns the orchids to the trees, each one to the correct host, since they are very selective and particular.

How does Tom accomplish this?

“I simply use a stapler, and staple them to the trees! They are very small staples and don’t penetrate beyond the bark of the tree, but it seems to hold the plant well until it can grow new roots. And the staple rusts away in time. Not a very elegant solution, but it seems to work fine. And they seem to enjoy their new home.”

Tom is just one of the people who love orchids. Neither collector nor scientist, he is just one of the growing number of people who respect the natural world and are prepared to do their bit to help when there is a problem. And, as we all know, there are very many problems today.

It wasn’t until I began to gather material for this chapter that I realized the full extent of the influence that orchids have exerted through history. Down through the ages discoveries of the most beautiful species have roused passions that have led to cheating, crime, and the most flagrant disregard of national and international law. It is the stuff of great drama and intrigue—and indeed many writers have explored the orchid sagas.

But this terrible history of greed and exploitation is only part of the story. A new breed of orchid lovers is now coming to the fore—those who are equally passionate, but for a different reason. They are prepared to fight to protect beautiful endangered orchids in their natural habitat and to persevere in efforts to restore others to their rightful homes in the wild.