Chapter 10

Plants That Can Heal

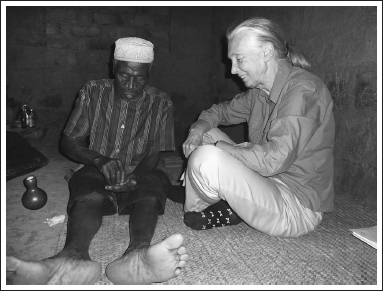

Part of our TACARE mission in Gombe is to learn about and protect the knowledge of the traditional healers. Recently I visited Mzee Yusuph Rubondo in his tiny house, and he told me that before he became a healer, he had learned about witchcraft. He said this was probably why he has become an expert in curing patients who have been “bewitched.” (CREDIT: © THE JANE GOODALL INSTITUTE–TANZANIA / BY DR. SHADRACK M. KAMENYA)

Many of the medicines my sister and I were given as children were based directly on ancient folk wisdom passed down, often orally, by those who were knowledgeable about the healing properties of different plants. They had wonderful names, our medicines—witch hazel, slippery elm, syrup of figs, friar’s balsam, dill water. Unfortunately, the taste of these plant extracts was usually not as delightful as their names implied—but my grandmother, Danny, was implacable, and as she stood over us, spoon in hand, we had no choice but to “open wide” and swallow the revolting stuff.

One of Danny’s favorites was Squill and Tilleul—which I always thought of as “Squills and Tooloo.” It was a disgusting cough medicine made, I have now discovered, from the resin of Tolu (Myroxylon balsamum), a tree native to North, Central, and South America, that acts as an expectorant, and from the bulb of squill, Urginea maritima, a Eurasian and African plant. No wonder I hated the stuff—squill is also used to make rat poison!

Gradually these old remedies went out of fashion, but now some of them are once again back on the shelves as herbal and holistic medicine in the United States and across Europe. This is not always good news—some of them have been shown to be harmful. Even so, herbal medicine seems to be a growing and highly lucrative market worldwide. In western Europe herbal medicine sales were five billion dollars in 2003–2004, according to the World Health Organization. In other parts of the world where traditional medicine is the primary form of health care—particularly in many countries of Africa and Asia—herbal remedies are especially popular. In China, herbal medicine sales were as high as fourteen billion dollars in 2005.

Healers of the Waha Tribe

Part of the Jane Goodall Institute’s TACARE (“Take Care”) program in Tanzania is devoted to learning about the local traditional medicines, mostly by talking with the indigenous healers, or traditional medicine practitioners, as they are often called.

I was fascinated by this aspect from the start, as were Emmanuel Mtiti, director of TACARE, and Aristides Kashula, our forester. Kashula was the first of our team who began traveling to different villages to talk to the medicine men and women. And although it often was not easy, he gradually won their confidence and eventually they began to share their knowledge.

This was important—more and more of the medicinal plants were becoming highly endangered due to habitat destruction, and knowledge of their uses was also disappearing as the old traditional healers died and youth, for the most part, was scornful of the old ways. So we wanted to try to protect, cultivate, and learn about that wisdom before it was too late. We have now been able to work with a total of eighty-six medicine men and women, all of whom stated that almost every plant has some kind of healing power. The medicine may be contained in leaf, flower, seeds, pith, root, or bark, or some combination thereof. It would take a long time to make a complete “herbal” of local medicinal plants—indeed, it would be almost impossible, for different healers use plants in different ways, to cure different diseases.

In February 2012, I went with Shadrack Kamenya, a member of our Gombe research team, to meet with two of these healers in their homes. These days only a few of the very oldest women still wear the traditional clothing of the past—the two men I met with were dressed in normal Western-style shirts and trousers. And although their parents had spoken only the local Kiha language, these men spoke Kiswahili, the national language of Tanzania, as well.

First we visited with Mzee (the respectful form of address for an elder) Mikidadi Almasi Mfumya of Bubango Village. We sat on low stools just inside the door to the tiny living room (only about six feet by five feet) of the house (itself only a little more than thirteen feet square) where he lives with his family. He told us he was now sixty-five years old and that many of the plants he knew as a young man had disappeared along with the destruction of the forests around his village.

He had a large collection of jars and pots and gourds for mixing and storing his remedies. Many of them, he explained proudly, had been handed down from his grandmother. He picked up one or two of the wooden bowls to show us, handling them with reverence and respect. It was from his grandmother, he said, that his own mother had learned the skills that she had passed on to him.

What he is best known for, Mzee Mikidadi told us, is treating snakebites. He uses ground-up leaves that he buys from the Wabembe, the indigenous people of eastern Congo, many of whom have settled in the Kigoma region. I asked him if he had cured a lot of people and he assured me that they almost always recovered if they got to him soon enough. And he was sure his mother was still helping. “Her spirit talks to me,” he said, “and so I know when patients are coming and can have all the medicine ready when they arrive.”

Mzee Mikidadi took us around his little plot at the back of the house where he is now growing his own medicines. Trees and plants thrived in a riot of green leaves, gnarled trunks, and tangling vines. He showed us one young ntuligwa tree, known to some as “governor’s plum” (Flacourtia indica), growing on a termite mound. He had had to get it from some distance away, since all such trees have vanished from his area. Traditional wisdom maintains that the medicine is always most effective if the leaves from which it is made are picked from trees that are growing on a termite mound.

I was fascinated to hear that Mzee Mikidadi always talks to a plant, asking it for permission, before using it for medicine. “I always leave a gift,” he told us, “an offering for the spirit of the plant. And then I return to take what I need.” I have been told exactly the same by a First Nation healer, who speaks to his plants and leaves them gifts of tobacco.

We said good-bye to Mikidadi and drove to Chankele Village to talk with Mzee Yusuph Rubondo, a well-respected elder who thinks—but has no way of knowing for certain—that he is eighty-five years old. When he started practicing as a young man, there were, he said, many chimpanzees in the thick forest all around his village. And all the medicinal plants were present as well. He told us he had acquired his knowledge from his mother and father, both of whom were healers: his mother had learned from her father, but his father had learned from a man who was not closely related at all.

We followed him into his house (also very small—the whole structure no bigger than twenty-by-twenty-two feet), and I sat with him on a rush mat laid out on the earth floor at one end of the living room. It was somehow mysterious in there, dimly lit by the light that came in through the one very small window. Arranged neatly on the ground beside him was a fascinating collection of little jars and bottles, most of them carefully wrapped in plastic bags. This was his “drugstore” of powders, dry leaves, seeds, and so on that he uses to treat a whole host of different medical conditions, ranging from toothache to coughs, from rheumatism to fevers.

He had started off, he said, learning about witchcraft—and perhaps that was what had helped him to become an expert in curing patients who had been “bewitched,” as he called it. I asked him if he saw many such people, and what their symptoms were.

There were many, he said. Some arrive lethargic and dull. Others are shouting and screaming, occasionally trying to take off their clothes, and then he needs help to restrain them and hold them down, before he can treat them.

The medicine he uses comes from a plant that he dries and grinds into a powder. He called it kikali, but it may be that he was simply using the Kiswahili word to indicate that it was strong medicine. He took the lid from a container made from a small round polished gourd, chestnut brown in the dim light, and showed me a pale gray-brown powder. Then, taking a pinch, he demonstrated how he treated a patient by rubbing it into his own arm. After that, with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes, he did the same to me!

I could have sat listening for a long time as he talked of the changes he had seen in his long life. Some, he said, are good changes—he likes his cell phone. But other changes have been disastrous, such as the growth of the population, the changing weather patterns, and the gradual destruction of the forests that supply most of the medicines he needs. Many of the plants that were once common in his backyard must now be searched for, farther and farther away.

Two of our own Gombe staff are skilled in the use of medicinal plants, and Shadrack, who has spoken with them at length, tells me how some of the plants seem to have helped people with a whole variety of diseases and infections—including HIV/AIDS.

I asked Shadrack if there was proof that anyone had actually been cured of that. He said he had met several people who arrived from various regions of Tanzania looking thin and very sick, and had been told that they had AIDS. And then, following their treatment, which lasted a few weeks, they had gone off looking well and healthy. But there was no proof, he said, that they had actually become HIV negative. Still, if there is a medicinal plant that alleviates the symptoms and gives people better health and longer life expectancy, this would be wonderful.

Animal Physicians

How did traditional healers first learn about the healing properties of plants? Through trial and error? Some kind of instinct? Or perhaps, from watching animals?

About a century ago a Tanzanian medicine man, Babu Kalunde, discovered that the roots of a plant known as mulengelele to the local Watongwe people, was powerful medicine, and as a result probably saved the lives of many people in his village when there was an epidemic of a dysentery-like illness. Babu had watched a young porcupine, who had symptoms similar to the sick people, digging up a mulengelele and eating its roots. He was amazed, as he had thought that the plant was extremely poisonous. But now the situation was desperate, so Babu took a tiny dose himself. There were no ill effects, so he persuaded the sick people to try the plant—and it helped. To this day the Watongwe use mulengelele as medicine. Babu’s grandson, now a respected elder and healer himself, uses it to treat a number of different diseases.

Many dogs eat grass from time to time. I have known many dogs over the years—two of them zealously selected blade after blade, chewing them up with great gusto. Occasionally this would cause them to vomit.

There has been much speculation as to why dogs eat grass. Some believe that they just like the taste—as I love eating spinach leaves. Others think dogs do it instinctively when they feel unwell, to stimulate a vomiting response, which may help them to get rid of whatever made them feel sick. There is a school of thought that believes the grass may help to clear the intestines of parasites. Or that the dog needs more fiber in the diet: one poodle, who had regularly eaten grass for eight years, stopped once she was fed a high-fiber diet.

That animals have an instinct to cure themselves seems pretty conclusive. A recent study showed that female monarch butterflies infected with a deadly parasite lay their eggs on a particular species of milkweed that reduces the risk of the caterpillars becoming infected. They thus provide their young with medicine. Other tests show that sick domestic animals, when given a choice of foods, mineral supplements, and so on, will choose one known to be useful in treating their symptoms, perhaps detecting the medicinal properties through smell.

On a number of occasions, when one of the Gombe chimpanzees had an infected wound, we “laced” bananas with tetracycline by making a cigarette-sized hole at one end, dropping in the powder, and pressing the opening closed. We tried to follow the sick individual for four days, offering one of the bananas four times a day. What amazed me was that whereas a sick chimpanzee accepted and ate the fruit without hesitation, once he or she was better, such bananas were rejected after a cursory sniff.

It should not be surprising that chimpanzees are also able to treat some of their own illnesses. In the 1960s, during the early years of my study at Gombe, we used to check the chimpanzees’ dung to get some idea of the frequency with which they ate different foods. We found many seeds that had been swallowed along with the fruit—the plant was using the chimps to distribute its progeny. And every so often we found long, narrow leaves with stiff hairs underneath that had been swallowed whole. I pressed them (after a thorough washing!), along with the other food plants, and sent them to Bernard Verdcourt to identify at the herbarium in Nairobi. They were, he said, leaves of Aspilia pluriseta, of the daisy family.

Richard Wrangham, before he became an eminent professor at Harvard, had studied chimpanzee feeding behavior at Gombe and he noticed that the chimpanzees used their tongues and lips to roll Aspilia leaves into a sort of cylinder, with the plant hairs on the outside. Instead of chewing them, they would then swallow them whole. When he heard that the local villagers used this plant as medicine as well, we were all excited.

Since then Dr. Mike Huffman has made detailed studies of the use of Aspilia by chimpanzees, lowland gorillas, and bonobos. At first it was suspected that the leaves contained some kind of chemical, but in fact it is the physical characteristics of the leaves that are significant—as they pass through the stomach and intestines, the stiff hairs flush out the nematodes and tapeworms that tend to multiply during the rainy season.

Many animals medicate themselves with plants. This chimpanzee is eating Aspilia pluriseta to help flush out nematodes and tapeworms from the gut that flourish during the rainy season. (CREDIT: MICHAEL A. HUFFMAN)

Some hundred miles south of Gombe is the Mahale Mountains National Park, site of an intensive chimpanzee study carried out by the Japanese since 1966. There the chimpanzees make use of the extraordinarily bitter pith of Vernonia amygdalina, also of the daisy family. This plant, found in most African countries, is used by people as a treatment for, among other things, malaria, internal parasites, and lack of appetite. It is also used by chimpanzees infested in the rainy season with the nodule worm Oesophagostomum stephanostomum. Mike told me of two cases when chimpanzees who were clearly sick—they had lost weight, were lethargic, and were known to have a nematode infestation—had spent time chewing Vernonia pith. Between twenty and twenty-four hours afterward, both showed definite signs of recovery.

Subsequent research in the lab has shown that Vernonia pith is indeed effective against certain microorganisms that infect both chimpanzees and humans. The scientists also isolated two chemical compounds from the pith that actually suppressed egg-laying activity in a common parasitic worm. How chimpanzees know they should take these medicinal plants is still a mystery. Mike suspects the chimps—and many other animals—are actually using even more plant species as medicines.

And not only as medicines: in Calcutta, S. Sengupta and other naturalists observed that a pair of house sparrows lined their nests with neem leaves at hatching time. It seems they somehow know that the leaves act as a pesticide. To make sure that it had not been an accidental choice, the nest lining was removed—again the birds selected neem leaves as a replacement.

The Neem Tree—“Nature’s Drugstore”

The neem (Azadirachta indica) is an evergreen of the mahogany family that can reach heights of around one hundred feet. It originated in the Indian subcontinent, where it is common in backyards—and it continues to grow in suitable wild habitats as well. For more than 4,500 years Indians have known that all parts of the neem tree have medicinal value—extracts from leaves, bark, flowers, seeds, and roots have been and are being used to treat an incredible number of different medical conditions. The Indians’ appreciation of its virtues is reflected in its many names: “nature’s drugstore,” “panacea for all disease,” “tree of forty cures,” “village pharmacy,” “heal all”—and in one area, “the sacred tree.”

It has been especially valued for its properties as a pesticide, and various preparations are used to protect crops in the fields. Oil from its seed protects stored crops for around twenty months. Neem “cakes” dug into the earth promote good growth, repelling insect pests and plant diseases, storing nitrogen, and encouraging the proliferation of earthworms to aerate the soil.

In 1959, during a terrible plague of locusts in Sudan, German entomologist Heinrich Schmutterer noticed that whereas the voracious insects consumed just about everything that grew, leaving leafless trees and bare fields, the neem trees were still green once they had moved on. The locusts would land on the foliage—but then fly off. They were repelled. It was this that caught the attention of Western scientists, although it would be another thirty years or so before the huge potential benefits of the neem tree—for agriculture and medicine—were more widely appreciated.

This tree was brought to Africa by the Indians and now grows in many parts of the continent. The word we use for it in Tanzania is arabaini, which in Kiswahili means “forty” and refers to the fact that it has at least forty different uses, including the treatment of malaria.

“Try one,” my son, Grub, urges me, handing me a small green leaf from the neem tree in our garden in Dar es Salaam. I know how it tastes, but I bruise the little leaf with my teeth anyway. At once my face contorts—it is incredibly bitter. I reject the rest, and watch with amazement as Grub, who has already chewed up five of these leaves, swallows a couple more. He has a headache and thinks it could be heralding a bout of malaria—he has been forgetting to chew his daily couple of leaves and is now making up for it.

I have a Tanzanian friend, Christopher Liundi, who grew up in Dar es Salaam. His mother had forced him to drink an infusion of neem leaves once a week. “It was so bitter I could hardly get it down without vomiting,” he told me. But it was worth it—Chris has never had malaria, a miracle for someone living in an area so teeming with malarial mosquitoes.

My mother and I both got very sick with malaria when we first got to Gombe. Side by side we lay in our shared ex-army tent, too weak to go into town to seek treatment. We eventually recovered, though I think my mother, whose temperature rose to 105 degrees Fahrenheit for five days running, nearly died.

The Roots of Quinine

Indeed, malaria is a common and often deadly disease throughout the tropics, especially for small children and people newly arrived in a malaria area. But it was not the neem but the cinchona tree (Cinchona spp.), a member of the coffee family, that would provide a cure. Without that discovery, the history of colonial settlements in Asia, Africa, and the Americas might have been very different.

There are over forty species of cinchona, all found in the tropical Andes—in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. It is the bark of this tree that is so important—it contains many chemical compounds known as alkaloids, one of which is quinine. I knew about quinine from an early age, as I had an aunt and uncle living in India, and my father was stationed in the Far East during World War II. They all told me about the quinine tablets they had to take each day to protect against malaria. It was because of the small amount of quinine found in tonic water that “gin and tonic” became the drink of choice for expats and others living in the tropics. And I cannot resist adding here that when there was a bad outbreak of avian malaria in Calcutta, the naturalist Sengupta’s little sparrows actually exchanged the neem-leaf lining of their nests for the leaves of the paradise flower tree (Caesalpinia pulcherrima), which is rich in quinine. They also ate the leaves.

In the sixteenth century, Spanish settlers in South America discovered that local indigenous people had, for hundreds of years, been using powdered cinchona bark as a treatment for fevers, and it seems that Jesuit priests first introduced the wonder bark to Spain. By 1630 regular shipments were being sent from Peru to Spain, from whence it was traded to other European countries. Word spread and the demand grew. By the early 1800s cinchona bark was seen as essential for the health of all those administering the European colonies in tropical areas around the world.

As all this bark came from trees growing in the wild, it soon became impossible to meet the constantly increasing need for the bark, and prices soared. Finally, in 1820, two French chemists were able to extract, from the bark, an alkaloid that had antimalarial properties; they named it “quinine.” But even though quinine soon became commercially available, demand for the complete, natural cinchona bark continued, and in the mid-1850s, Peru and Bolivia tried to retain their monopoly on the export of cinchona seeds and seedlings.

The British promptly sent that intrepid explorer of the Amazon Richard Spruce to find another supply that they could grow in their overseas colonies. He was able to get some seeds and plants of a cinchona, C. succirubra, from Ecuador. They grew readily, and cinchona soon became the most widely planted species in British colonial India, Sri Lanka, Jamaica, and East Africa.

At about the time Spruce was searching for seeds in Ecuador, one Charles Ledger bought seeds of a species of Cinchona from an aboriginal trader in Bolivia. He tried to sell them to the British, but as Spruce’s collection had just arrived, no one was interested. Ledger therefore sold his seeds to the Dutch, and this led to their extremely successful Cinchona plantations in Java.

It is hard to overemphasize the major role that quinine, our gift from the Cinchona tree, has played in world history. Only when colonialists had access to this drug did West Africa cease to be known as “The White Man’s Grave.” It was when supplies from plantations in Java were cut off during World War II that the United States established its own plantations in Costa Rica. But before these trees could mature and provide a new source of quinine, hundreds of thousands of US troops died in Africa and the South Pacific due to lack of the drug. Indeed, it is said that there were more deaths from malaria than from all the bullets and bombs combined.

Quinine is still used in treating some forms of malaria that have become resistant to the latest drugs, though usually as a last resort, because it can have some unpleasant side effects. I know about these from personal experience. I was in Dar es Salaam, suffering from one of my frequent bouts of the disease, and was persuaded to seek help from the physician attached to the American embassy at the time. He took a blood test and, staring at the multitude of parasites wiggling about under his microscope, concluded that my death was imminent. Afterward he told me that the only other person he had seen with as high a count had indeed died. Panicking, he gave me a double dose of quinine. It cured the malaria, but I became almost stone deaf and had blurred vision for several days.

The Miracle Drug of Folk Medicine

Another plant whose incredible power to heal was confirmed by Western medicine is the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus), a member of the dogbane family, a common little plant in southeast Madagascar. Because of its pretty flowers, this periwinkle got its early fame as an ornamental bedding plant—and by the eighteenth century it had proliferated in many gardens and botanical gardens throughout much of Europe. Soon it had escaped to colonize suitable areas in the country as well as vacant lots. Gradually it adapted to the different climates in which it now lives, becoming a garden annual in temperate zones and a perennial shrublet in the tropics. We have rosy periwinkles in our garden in Dar es Salaam.

But this plant is a lot more than an attractive garden flower. In its native Madagascar, traditional healers always used it as a remedy for a number of diseases. And as it traveled farther and farther around the world, more and more people began talking about its healing properties—although it can be toxic if used improperly. It is a widely used drug of folk medicine, prescribed by herbalists in southern Africa, India, Australia, the Caribbean, and the Philippines—for constipation, toothache, malaria, and diabetes. It was this last claim that attracted the attention of Western medicine.

In 1952 Dr. Robert Noble, of Toronto University, received a package of twenty-five leaves from his brother, Clark, in Jamaica. He had been told that an infusion of the leaves was used to treat diabetic patients when insulin was not available. Robert Noble and his team ran tests and found that while there was no evidence that the plant could help diabetics, it contained alkaloids that could arrest the growth of blood cancers.

Six years later, Noble, now joined by Dr. Charles Beer, and their team, isolated and purified a potent alkaloid extract—vinblastine—and suggested it be tested as a treatment for childhood leukemia. The results were very promising, but it took twelve tons or more of dried periwinkles for one ounce of vincristine sulfate, and there were bad side effects, including hair loss. Clearly further research was necessary, but the team persevered, and today the extract from the rosy periwinkle, in combination with other alkaloids, is the main weapon against childhood leukemia. Many have recovered completely—and all because of a little Madagascan plant.

Stopping Biopiracy—The Theft of Indigenous Plants and Wisdom

When I was thirteen years old, my uncle Eric, who was a surgeon, told us about a new anesthetic—curare—that was derived from a liana (Chondrodendron tomentosum). It grew in the rain forests of South America, where it was used to poison the arrows and darts of indigenous tribes of the western Amazon. At his hospital they were calling it “jungle juice.” Interestingly, the extracts from this plant, though highly lethal when injected or rubbed onto a wound, are harmless when taken orally—which explains why poisoned prey can be eaten with no ill effects.

In 1804 the medical potential of curare was first suggested by British naturalist and explorer Charles Waterton, and in 1942 it made its debut as a “wonder drug” that would relax muscles during anesthesia. Soon after, my uncle began to use it. But it was not until years later that I began to think about the indigenous people who had discovered the power of the vine that could kill. How had they been affected by Western interest in this plant?

I got some of the answers from Dr. Mark Plotkin of the Amazon Conservation Team, a Westerner who has spent three decades studying the relationship between the plants and the shamans of the Amazon rain forest. Ever since he first went there as a young man as part of a group studying crocodilians, and was introduced to the indigenous tribes by Dr. Richard E. Schultes, he was hooked—on plants, on the indigenous people, and on the Amazon. Since then he has been learning about the many medicinal plants that are used in the forests, as well as searching for new plants that can heal. And it was he who drew my attention to the fact that certain Western drug companies had sometimes made huge profits from medicines derived from tropical plants and animals. And they had learned about some of these, including curare, from local tribal peoples.

Mark and other ethnobotanists (scientists who study the plant lore and customs of people), who were concerned about the plight of many of the indigenous tribes—their forest environment increasingly destroyed, their cultures compromised, their lands seized—started to wonder whether it might be possible to create regulations regarding collection of indigenous plants that would not only benefit the tribes but also help conservation efforts.

Mark Plotkin (right) has spent a quarter of a century learning about and documenting the indigenous wisdom of the Amazon. Here he attends a recent unprecedented gathering of shamans from seven tribes. They realize that it is desperately important to share their knowledge, to pass it on, to preserve it before it is too late. (CREDIT: MARK PLOTKIN)

They began working with other organizations and international lawyers to develop new guidelines to ensure that all parties get a fair deal. As a result, those who now search for specimens for possible medicinal, agricultural or industrial use—known as bioprospectors—must comply with various regulations or they could incur severe penalties, including imprisonment.

It is a complex system, comprising international treaties, national laws, and a good deal of professional self-regulation. The collectors must get all necessary permissions and agree to certain conditions, to ensure that the indigenous people of the forest, as well as the resource country, get a fair share of any profits. And if material is removed illegally (biopiracy), the resource country can recover all or some of the profits made from its use. But although these regulations have certainly helped, there are still many threats to the well-being of both plants and people.

One of the most powerful voices speaking out against the overexploitation, or even theft, of indigenous wisdom by Western corporations is the philosopher and environmental activist Dr. Vandana Shiva. Of particular concern for her is the patenting of products derived from an indigenous plant. She sees this as a new sort of colonialism: “In the old way they took over the land—now they are taking over life.”

She describes the successful efforts of American companies to patent a chemical found in the neem tree for use as a pesticide. It began in 1971 when American timber importer Robert Larson brought neem seeds to the United States and was able to extract the active pesticide ingredient (an isolated molecule named azadirachtin). He got a patent, and seventeen years later sold it to the pharmaceutical giant W. R. Grace & Co.

Since then, patents for neem-tree products have been granted to companies in many countries, including India. W. R. Grace, owning some of these companies, set up a base of operations in India and tried to buy the technology of Indian scientists who were working to develop their own products from the neem tree—not surprisingly, there was strong opposition.

Meanwhile W. R. Grace continued to develop new neem-derived products. Vandana Shiva was incensed. In one of her many articles she writes, “Grace’s aggressive interest in Indian neem production has provoked a chorus of objections from Indian scientists, farmers and political activists who assert that multinational companies have no right to expropriate the fruit of centuries of indigenous experimentation and several decades of Indian scientific research.”

Of course, all this has led to heated and ongoing debates, spanning many continents. Should it be possible to patent a substance derived from a wild plant? And how do we define intellectual property when it is connected to indigenous medicinal plants?

We must be grateful to the scientists who extract medicines from the earth’s healing plants. But we must recognize, too, that it is important that indigenous communities in the source areas be able to maintain their cultural traditions and practice their own healing skills. It is essential also to protect the plants themselves and their environment, and people are more likely to care about and nurture their plants if they see there is value in doing so—if we help them to get some share of the dollars that can be made by the pharmaceutical companies, governments, and private investors. Only in this way can we hope to protect the diversity of plant life upon which, ultimately, we all depend. Unfortunately, though, many medicinal plants are threatened by overharvesting.

We Are Losing Our Medicinal Plants

My Native American friend Chitcus, a medicine man of the Karuk tribe in California, always uses kishwoof in a small ceremony. Kishwoof is a root that is traditionally used for healing and “smudging,” a ritual in which smoke from burning various sacred or medicinal plants is used to purify. Chitcus smudges me by burning kishwoof in an abalone shell. He moves a bald eagle feather through the smoke repeatedly and then taps me with it, slowly moving around my body and chanting a blessing. He pays special attention to my feet because, he says, they have to take me so many miles around the world!

Just before the last time Chitcus and I met, he went to gather more kishwoof from the place where he had gathered the root for the past twenty-five years, and where his uncle had harvested it some thirty-five years before that. They had always taken only amounts sufficient for their immediate needs. But on this occasion, Chitcus told me, he found that the whole area had been desecrated, stripped of nearly all plants. He eventually discovered that “pickers” had been sent out in the spring to collect roots, which were then ground up and sold by herbalists.

The pickers “have harvested all of the sacred old Master Roots!” Chitcus told me. “Now the hillsides stand bare with nothing but potholes all over the ground.” He and his sons now have to climb to very high, almost inaccessible places to gather the material they need—only taking a little from each plant so that it can regenerate.

Chitcus also told me how the same zealous overcollection had once threatened the Pacific yew, a tree that is widely used by Native American tribes for making bows and other utility objects. It is also highly valued as a medicinal plant and used in smudging ceremonies. Chitcus had been told of the many “pickers” sent into the forests of the Pacific Northwest to collect bark for Western medicine. His mother, also a healer, had explained how the pickers would cut the tree to the ground so much so that it could not regenerate.

That story began in 1960, when the National Cancer Institute, in partnership with USDA, commissioned several botanists to collect plants that could be tested for their anticancer potential. One of the samples was a piece of bark from a Pacific yew. The yew was one of the few that showed promise: more bark was collected, and five years later the active ingredient—taxol—had been isolated. As work continued, more bark was needed—and, as Chitcus remembered, the collecting process had resulted in the death of the trees. Over the next twenty years encouraging human trials began. More and more bark was needed, more and more wild yew trees were killed. The bark of one tree only provided enough taxol for about one dose. By the mid-1980s taxol was being used to treat breast, ovarian, and cervical cancer.

This was very exciting, but when the scientists announced that by 1987 they might need sixty thousand pounds of bark to meet the demand for the drug, serious environmental concerns were raised. How long could the wild yew trees sustain harvesting of this sort? Obviously it was imperative to find some other way to make the drug, and several scientists around the world intensified their efforts. As a result, by 1993 a successful product had been developed using plant-cell-fermentation technology. An effective cancer medicine no longer relied on collecting bark from the Pacific yew.

Technology and know-how have increased, and it is not always necessary to destroy wild plants to create new drugs. Instead another threat looms—the growing global love affair with herbal medicine.

Ayurvedic medicine originated in India and is considered one of the oldest healing traditions in the world. This holistic approach to health incorporates many plant-based therapies, and most of the herbs are still harvested from the wild.

When this medicine became more popular in the West, exports grew rapidly, and suddenly, in 2010, it was found that 93 percent of the most important wild-harvested herbs were endangered, mostly because of reckless harvesting by those who sought immediate profit. Collectors were tearing the whole plant out of the ground, whether or not all parts were needed, thus reducing the chance for the harvested area to recover.

Some of the most common over-the-counter herbal remedies in the United States, such as American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), and echinacea, also known as purple coneflower (Echinacea angustifolia), are now listed as endangered, mainly because of the increase of unsustainable harvesting methods.

Passing on the Wisdom

What a tragedy that just as we are beginning to appreciate the wisdom and knowledge of traditional healers and shamans, so many of the plants are vanishing—or gone. Fortunately, people are waking up. Old Mzee Rubondo, the traditional healer of the Waha tribe in Tanzania, realized he had to do something about his vanishing medicinal plants on the day he had to travel 160 miles to find one that he desperately needed—a plant that had once grown close to home. He told me that was an expensive journey that he could ill afford—the loss of the forest was a personal loss that was also hindering his work and affecting the health of his community.

That was when he decided to take part in our TACARE programs. He knew about them—he told us that our conservation initiatives were really making a difference, and that in all the places where he had searched for particular plants, people had talked about our work and were more willing to help him. Mzee Rubondo, and many of the other traditional healers, are now taking an active role in collecting and protecting medicinal plants, and helping to restore forest habitat.

In Tanzania the Roots & Shoots members of Sokoine Primary School are learning how to identify and draw their local indigenous medicinal plants. (CREDIT: SMITA DHARSI)

Mzee Rubondo was particularly appreciative of JGI’s environmental education program, as he, along with other healers in the area, believe that if people know which plants are used to treat different diseases, they will be more likely to help in protecting them. They all encourage Roots & Shoots club members to learn the names and uses of the plants that grow in the area. They are desperate to pass their wisdom down to the next generation.

During my last visit to Kigoma I visited the Roots & Shoots group of Sokoine Primary School. They showed me the regeneration that has taken place in the fifteen-acre forested area they have been protecting since 2004. Club members, with the help of local volunteer Isaack Ezekia, have been identifying all the rare plants growing there, especially the medicinal plants. Isaack told me they are so enthusiastic that when he offered to hold a workshop during their holidays, they all wanted to take part. He taught them more about the uses of the plants, their scientific names, and how to draw them. Isaack did not realize that the father of one of the pupils, Fedrick Fowahedi, was a well-known traditional healer, and was apprehensive when the child said he was taking specimens of the plants home to ask his father if what he had learned was true. To Isaack’s immense relief he was told he had got it all right.

Now the members are eager to write a science book for children that will include the names and uses of all the traditional medicinal plants found in the forest.

In the Amazon, too, says Mark Plotkin, there is a race to preserve the ancient cultures of the indigenous people before it is too late. The shamans, traditionally leaders as well as medicine men and women, were finding it increasingly difficult to pass on their knowledge. As in so many parts of the world, the younger generations tended to scorn the old traditions as being irrelevant in a rapidly modernizing world.

The Amazon Conservation Trust was established, in part, to try to help the medicine men and women with the vital task of passing on their wisdom to the next generation of their tribe. An imaginative program pairs a shaman with a young apprentice whom he can teach about medicinal plants. They make a medicinal plant garden, and the apprentice, if he can write, keeps a written record of the shaman’s knowledge—for which he gets a small stipend. The program is working. There are now regular gatherings of shamans from the northern Amazon, who meet to share knowledge, discuss problems, and celebrate successes.

Tanzanian Roots & Shoots volunteer Isaack Ezekia (center) is teaching the local primary school children about their medicinal plants. R&S member Fedrick Fowahedi (left), the eleven-year-old son of a respected traditional healer, is one of those responsible for caring for the school’s forest garden. He has been watching over this endangered tree that he had found and transplanted in the garden, and was eager to explain how its leaves and bark are used to cure a variety of illnesses. (CREDIT: NICOLAS IBARGUEN)

I suspect that some of those shamans share the sentiments of old Mzee Rubondo in Tanzania. When I asked what he thought about the future of his work, he replied, “We cannot afford to lose our plants, because agreeing to lose them is like agreeing to die. But if we replant lost species and conserve the forests, then our plants will survive—and so will we.”

Hope for Future Harvests

Fortunately, this kind of understanding is spreading, and practices are changing. In India, where the Ayurvedic medicinal plants are so threatened, the government has defined “sustainable harvest protocols,” designed to prevent people from ripping out entire crops or decimating a habitat. It has also created conservation areas in India where there is the greatest diversity of medicinal plants, and hired locals to monitor and protect these areas.

In Sri Lanka, where overharvesting is also threatening medicinal plants, the government is developing community-farming projects for growing Ayurvedic herbal plants. The sale of these plants directly benefits local economies, and helps to provide much needed support for the upkeep of the Mihintale Sanctuary, believed to be the oldest wildlife sanctuary in the world. Established by King Devanampiya Tissa some 2,200 years ago, in the third century BC, there are stone inscriptions telling people not to kill animals or destroy trees. And there is a high level of medicinal plant diversity.

Herbal medicine has been part of the Chinese culture for at least two thousand years, and it has become increasingly popular, both in China itself and throughout much of the Western world. However, this popularity means, unfortunately, that many of China’s medicinal plants have become endangered in the wild. But there is hope—numerous international NGOs are now working closely with villagers to introduce new ways to sustainably harvest medicinal plants while also making a good profit.

During my last visit to China, I was invited, along with a small group, to visit Jane Tsao’s organic farm near Chengdu. After showing us around the fields and greenhouses, Jane took us to a lovely, unspoiled woodland area along the banks of a river, where she is setting up a small nature reserve. As we walked in the shade of the tall trees, following narrow paths through ferns and shrubs of the woodland floor, I noticed a small, dilapidated wooden hut, half-hidden among the trees.

“It was once a forester’s hut,” Jane told us. “Now we are going to restore it and make a tiny education center.” It will provide information about the various local plants and trees that have medicinal properties. And it will also showcase some of the herbalists of the past who were wise in the knowledge of nature.

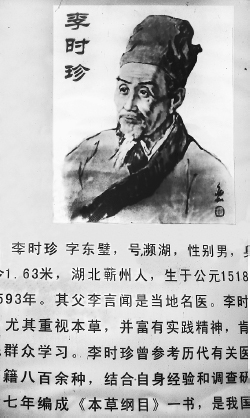

During my recent visit to an organic farm near Chengdu, I was fascinated to find, pinned to the wall of a disused forester’s hut, this faded print of Li Shizhen (AD 1518–93). Author of a giant encyclopedia on the uses of plants in medicine, he is widely revered throughout China today as a sort of “patron saint” of Chinese herbal medicine. (CREDIT: JANE GOODALL)

The portraits of those bygone healers, unprotected and faded, were pinned to the walls. I stood looking at them, my mind wandering to the very different China in which they had lived. And it seemed to me that despite their stern demeanor, they were offering a blessing on those who were trying to protect the natural world and the healing plants that they had understood and loved.