Chapter 13

Food Crops

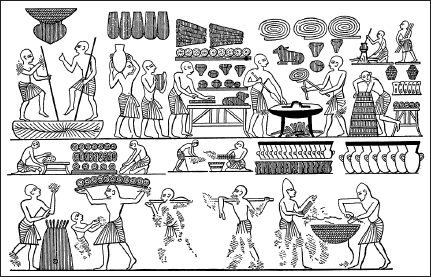

Wheat was one of the first farmed food crops, cultivated approximately eleven thousand years ago in Egypt. This etching, from the tomb of Ramesses III (who ruled from 1186 BC to 1155 BC), shows the step-by-step process of making bread from wheat at the royal bakery. (CREDIT: OXFORD ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANCIENT EGYPT, EDITED BY DONALD B. REDFORD [2001] P. 197. BY PERMISSION OF OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, INC.)

The gradual changes in farming techniques that have taken place over the ages enabled the digging stick to be replaced with the hoe and scythe, then the hoe and scythe with the ox- or horse-drawn plow, and these in turn with mechanized tractor, combine harvester, and so on, each new innovation enabling a farmer to work a larger area with fewer people.

The original organic fertilizers such as rotting vegetation and animal dung, especially guano, became increasingly supplemented by and then substituted with a variety of chemically synthesized fertilizers that, while beneficial to the farmer in many ways, began to take a terrible toll on the quality of the soil.

Various methods for irrigation of crops were devised over the ages. There were the irrigation ditches and hand-pumped artesian wells. Then boreholes were drilled so that water could be pumped up from deep down under the ground, from the aquifers. Then came center pivots, with their long arms distributing water in a wide circle around them. When you fly over the American prairies in the summer, you look down on hundreds of green circles surrounded by brown grass. Groundwater levels fell and aquifers were shrinking. And as more and more land could be used for agriculture, with corresponding growth of human populations in the urban areas, water from rivers was diverted for irrigation and more and more dams were constructed. There have been devastating environmental impacts.

The crops that, today, provide staple foods for millions of people around the world, and play a major role in sustaining our growing populations, are maize (which Americans call corn), rice, wheat, and potatoes. Maize comes first in terms of quantity produced globally—the UN figures for 2007 show that 790 million tons were produced globally. This compared with 657 million tons of rice, 613 million tons of wheat, and 324 tons of potatoes. Approximately 43 percent of the maize produced in the United States in 2012 was sold for biofuel—although there are signs that this industry is in trouble.

Wheat—Triticum spp.

I am starting with wheat because it was among the founder crops at the dawn of agriculture—archaeological evidence shows that it was grown on the first-known farms carbon-dated to 9000 BC. And because we use the grains of wheat to make bread, and bread has always been an intrinsic part of my own diet.

My grandmother Danny used to bake bread, and that heady aroma is a treasured memory from early days at The Birches. I can see her now, mixing the dough in a large ceramic bowl, wheat flour and water and yeast. Kneading it with her knuckles, letting us help by pulling it into ropes, then kneading it again, and finally covering it with a cloth and leaving it in the hot cupboard overnight to rise, through the action of the yeast. The next morning it would be baked in the oven. I would always try to steal the crust while the loaf was still warm and eat it with butter and homemade jam—even though Danny disapproved, as it was not good for the loaf. My sister makes bread today, but in a machine, and though the smell is wonderful, it does not seem quite as powerful. However, there are still artisanal bakeries in Europe where I can stand outside on the street, all my olfactory senses enraptured by the aroma in the air, and recapture the sensation of absolute bliss I knew as a child when Danny baked bread.

When I first visited Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire in the Republic of the Congo, both fairly small towns in a developing country, I discovered, to my surprise, that there were countless little cafés that emitted the same mouthwatering smell of baking bread. But of course it should not have surprised me, for Congo-Brazzaville is a former French colony. And in all their colonies the French introduced the art of producing delectable croissants, brioches, and crispy-crunchy French bread.

Wheat is a kind of grass. There are four species of wild wheat, and it is thought that their grains were collected for consumption long before the plant was first domesticated in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East. About two thousand years later, the cultivation of wheat began to spread throughout the ancient world, first to Greece, Cyprus, and India, then to Egypt and Spain. By 3000 BC it was being cultivated in England and Scandinavia, and a thousand years later it had reached China.

Not only was wheat among the first crops to be cultivated on a large scale, but surplus grain could be stored for long periods of time. This meant that numbers of people, many of whom were not involved in food production or procurement, could live permanently in one place. It thus played an important role in the development of the first cities.

Wheat is grown on more land than any other commercial crop—about 535 million acres around the world, and it thrives in amazingly diverse habitats, from near the Arctic Circle to the Equator, from sea level to the high plains of Tibet (thirteen thousand feet above sea level). Its grains are ground into flour that is transformed into bread and a thousand and one other culinary products. It is a leading source of vegetable protein, containing more than many other cereals. Whole-grain wheat is also rich in vitamins and minerals. Only the unfortunate people who must have a gluten-free diet are deprived of the beneficence of wheat. And even they, most experts agree, can drink Scotch whisky, made from fermented wheat grains, provided the beverage has been properly distilled.

My late husband, Derek Bryceson, told me that after World War II the British government came up with a plan to feed the people of war-torn Britain by developing more wheat production. One of the places they chose to do this was Tanzania (then named Tanganyika). Ex-servicemen were offered the opportunity to get degrees in agriculture, and given the chance of managing wheat farms in one of three areas (most of Tanzania is too arid for successful wheat farming—as was one of the three areas selected).

Derek was one of those men. He had served as a pilot and was shot down early in the war, losing partial use of both legs. Nevertheless, having obtained his degree at Cambridge University, he was able to persuade the authorities that he would be able to handle one of the farms on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. He was very successful, only leaving his farm in order to support Julius Nyerere in his campaign for the presidency of the newly independent country. When I met Derek, he had become a member of Nyerere’s first government—at the time he was the only freely elected white MP in black Africa. He was also the director of Tanzania National Parks.

Derek did not talk much about his farming years, but he frequently told me how he had loved to look out across his wheat fields, the young green of the new growth, the golden stems rippling in the wind before harvest. And this against the backdrop of Mount Kilimanjaro, tallest mountain in Africa, crowned by a snow-covered peak.

Potato—Solanum tuberosum

Toward the end of March 2012, I was in the United States being driven from the airport to the University of Wisconsin. The country there is flat, and we passed through farmland. I asked our driver what crops were produced. Corn, sugar beet, and potatoes, he told me. My mind drifted back in time to the days in England when I used to help with the potato picking on the farm owned by Miss Bush, who also ran a small riding stable. It was backbreaking work, potato picking by hand. I and two or three others, each with a large sack, followed after the plow—or whatever machine it was that moved through the rows, digging up the earth. We put the exposed potatoes into our sacks, working quickly to try to keep up—but it was certainly worth it, as it earned me free rides.

During the first year that I helped with the potato picking, a beautiful Shire horse named Paddy pulled the plow, but by the following year he had been retired and replaced by a tractor. I was very proud when I was allowed to drive that, but not nearly as happy as I was when I had been allowed to walk along leading Paddy by his bridle.

After a day’s work, we had to sort the potatoes into three different categories—those suitable for market, those that were slightly damaged or too small (those went for making chips and potato crisps), and the badly damaged ones (which were fed to the pigs).

The potato is the starchy tuber of a plant distantly related to deadly nightshade. It originated in the South American Andes, where it still grows wild. We don’t know for sure when it was first domesticated—it could be anywhere from 11,000 to 2000 BC—but we do know it has been an essential crop in the Andes since the pre-Columbian era. It was “discovered” by the Spanish conquerors of the Inca empire in the second half of the sixteenth century. Spanish boats carried the delicacy to Spain, from where it reached England and was gradually transported around Europe—and eventually farther and farther around the world.

Initially the European farmers were suspicious of the strange new food, but it soon became a well-loved staple across Europe, especially in France, where it was grown over huge areas. One story indicating just how popular it became states that King Louis XVI and his wife, Marie Antoinette, were given a bouquet of potato flowers at the king’s birthday banquet. The king was so pleased with the flowers that he pinned a spray of them to his lapel, and a garland of the flowers was made for Marie Antoinette to wear in her hair. Several of the banquet dishes included potatoes, and soon after this endorsement from the royals the potato began to soar in popularity.

It has been suggested that the introduction of this staple food played a major role in the nineteenth-century population boom in Europe. At that time only a few varieties were known, and there was little genetic diversity. One variety, known as “the Lumper” (what a name!), was cultivated extensively in western and southern Ireland, where it provided cheap but nourishing food, and the Irish people depended on it heavily.

Unfortunately the Lumper had poor resistance to disease, and this led to disaster when a fungus with the decidedly ominous name of Phytophthora infestans began infecting and then decimating the Lumper potato yields around mainland Europe. The fungal infection spread rapidly, and soon it crossed the sea to Ireland and attacked the potatoes there. The infected potatoes came out of the ground looking moldy and covered with dark blotches. How well I remember reading about the terrible 1845 Irish Potato Famine, which lasted over three years. About a million people died, and another million, in desperation, emigrated to Britain, America, Canada, and other places. By the time Ireland achieved independence in 1921, its population was barely half of what it had been in the early 1840s.

Since those days, years of selective breeding have produced over one thousand varieties adapted to many environmental conditions. I was treated to a rare and delicious kind with a jet-black skin during my last visit to Spain. Until fairly recently it was assumed that these different varieties originated from a number of different wild ancestors, but DNA testing has now shown that all varieties are descended from an ancestor that grew in what is now south Peru and over the border into Bolivia. Today China and India are the main growers, although Canada has taken the lead in producing seed potatoes for most of the last one hundred years. Potatoes are still a major food source in Europe, especially in eastern and central Europe, where more potatoes per capita are produced than anywhere else.

It was, as I have said, our most important staple food during my childhood. Roast potatoes on Sundays, boiled potatoes on most other days, mashed potatoes (involving more work for my grandmother, who did most of the cooking) less often. Then there were new potatoes (harvested before fully mature), boiled with mint from the garden—the smell was mouthwatering. And my favorite, jacket potatoes, slowly baked in the oven, cut open so that a little butter (or margarine) could be added, then closed again to keep everything warm. My mother did not like the skin, but it was the favorite part for Judy and me, and we used to get half of hers each. Finally, of course, there are the memories of cooking potatoes in the embers of a campfire—the only problem being that the skin was usually too charred to eat. We did not have tinfoil in those wartime years.

Today, Judy and her daughter, Pip, bring in bags of soil so that they can grow potatoes in the garden. It is a somewhat costly way of producing a few potatoes—but they really are quite delicious, and I know that the two potato growers, like the peasants in Vincent van Gogh’s famous painting, feel a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction when they eat the fruit of their labors!

Potatoes are normally grown from “seed potatoes”—fully grown potatoes that, instead of being eaten, are stored in cold warehouses, cellars, and so on. Before having a license to sell, the farmer must submit his seed potatoes for inspection in order to ensure that they are disease-free. In the United States only fifteen out of fifty states are permitted to sell seed potatoes, as they have the required cold winters as well as long hours of sunshine in the summer. In the United Kingdom, seed potatoes are mainly produced in Scotland, which has the overall coldest winters.

After their chilly winter sleep, the seed potatoes are planted, and roots and sprouts quickly appear (indeed, they often develop in the kitchen if you keep a potato too long). Some of the sprouts grow leaves and rise above the ground. Others, known as “stolons,” grow horizontally just under the soil, and new potato tubers appear at their ends as small swellings. Like its poisonous relative deadly nightshade, which is also related to henbane and tobacco, the potato plant contains solanine—a toxin that affects the nervous system—in its leaves, stems, sprouts, and fruits. When a growing potato is exposed to light, concentrations of the toxin under the skin are increased and the exposed part becomes green. Sometimes stolons run along the surface of the ground instead of underneath it, and farmers must prevent “greening” by covering the new tubers with earth. Greening is also caused by aging and damage. When the soil temperature warms up, the plant stops growing and the tubers gradually swell. Eventually the plant dies back, the skin toughens, sugars convert to starch, and the potatoes are ready for picking.

Wisconsin is one of the states where it is permitted to sell seed potatoes. I think of my drive through the farmland, past the potato farms, and of how the fields and woodlands were brightened by trees bursting with white or red blossoms—beautiful to look at, although the flowers were a couple of weeks early. The temperatures the week before, the driver said, had been up in the eighties—in March! And there had been no “proper” winter, he said. If our weather patterns continue to change, if winters overall continue to get warmer, I suppose that the nature of potato farming will gradually change too. Probably climate change will affect many crops in many ways all around the globe.

Maize, Corn, Mealy Mealy—Zea mays

The maize plant—also known as corn or, in Africa, mealy maize or mealy mealy—has a tall, leafy stalk that produces one or more ears, each containing seeds known as kernels. When mature, this results in the familiar corncob. As you drive through the African landscape, you will see fields of maize growing near every little village, as well as a few plants nestled up to the dwellings themselves. Yet maize is not indigenous to the African continent.

Recent research suggests that it was first domesticated from its wild-grass ancestor, Balsas teosinte, in the Central Balsas River Valley of Mexico some 8,700 years ago. Then, somewhere around 2000 BC, it gradually spread into other parts of the Americas.

However, it wasn’t until about 2,700 years ago that people succeeded in growing maize on the higher slopes of the Andes. This increased the caloric intake of the people, transformed the economy of the region, and provided the groundwork for the eventual emergence of the Inca empire. I learned about this from Alex Chepstow-Lusty. Alex was a student at Gombe in the early seventies, studying plants and not chimpanzees. I lost touch with him, but met him again in early 2012. Today he works for the French Institute of Andean Studies in Lima, Peru. Growing the maize at that altitude was “an extraordinary plant-breeding event,” Alex told me. And it had only been possible through the application of organic fertilizers on a vast scale. The secret, Alex discovered, was llama dung! It is a fascinating detective story, which originated from Alex’s careful study of pollen grains in the ancient sediments of a lake eleven thousand feet above sea level.

My mother saved this drawing of maize from my school notebook. (CREDIT: JANE GOODALL)

Throughout the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, after the arrival of the Europeans in America, maize began its travels to Europe and then gradually around the world, carried by explorers and traders. It is a good-natured plant, able to adapt successfully to a wide range of climates and soils, and its kernels have become a cereal staple in many countries.

Certainly maize is now a ubiquitous crop throughout many parts of Africa. In East Africa every village has its patch of maize, harvested when the kernels are fully mature, at which time roasted corncobs skewered onto wooden sticks are eaten around the fire at night or offered for sale at the side of the road. I have tried these mature cobs, but to my spoiled palate the grains are too tough and not sweet enough—though they look and smell delicious.

One variety, sweet corn, has an unusually high sugar content, making it especially delicious right off the cob. It is harvested early when the kernels are soft, and eaten as a vegetable rather than as a grain. It was originally cultivated by several Native American tribes, and introduced to the white man by the Iroquois in 1779. When my son was small, we had a house outside Nairobi, and the previous owner had grown in the garden the best and sweetest corncobs I have ever tasted.

Then there is popcorn. Dried kernels heated with oil swell up—and pop. The result is the familiar crunchy, spongy snacks that have today—at least in the United States—replaced the chocolates and ice creams that were sold to cinemagoers in my youth. The smell of popcorn is an integral part of going to any movie theater in America today. This can be bad news, as some movie theater popcorn can be very unhealthy: in 2009 the Center for Science in the Public Interest reported that one “medium” serving of movie popcorn can contain as much as 60 grams of saturated fat and 1,200 calories—the equivalent of eating two Pizza Hut Personal Pan Pepperoni pizzas. But the unhealthy part of popcorn has nothing to do with the grain itself, and when I read that report, I contrasted it with the corncobs eaten in the African villages, simply roasted over the coals—how we do manage to contaminate nature’s gifts.

There is also increasing concern over the prevalence in our food of corn syrup, which is derived from maize kernels. It is cheaper than cane sugar, so it has increasingly replaced it in processed food products, especially in many of the packaged and fast foods. Not only are such foods linked to obesity, but a good deal of corn syrup is derived from genetically modified maize, which might cause health problems of another kind. Once again, we cannot blame the maize for the irresponsible way it is treated by those out to make money.

And there is another major concern. In North America fields and fields of arable land are given over to growing genetically modified maize to feed our modern hunger for meat and our modern hunger for fuel. To produce more and more food for more and more factory-farmed animals to feed more and more people around the world who want to eat more and more meat. Meanwhile other fields of arable land are given over to growing maize to fill empty fuel tanks rather than to fill empty stomachs. Thus despite statistics on the number of people who go to bed hungry, less than 15 percent of the annual crop of maize is grown for human consumption. Poor, denigrated plant.

Maize represents so much of what disturbs me about industrial agriculture. We have transformed an ancient, graceful plant, one that has in its original form provided top-quality nutrition to millions over thousands of years, into a genetically modified demon, one of the major sources of industrial-farming pollution and soil erosion, as well as a leading culprit in the growing obesity epidemic. And as a final twist, maize, instead of fulfilling its noble role of feeding people, is being used instead as a gasoline substitute to fuel our machines and as feed to fatten up our factory-farmed animals. Meanwhile, peasant maize farmers in Mexico, unable to compete with US-subsidized farmers, have sunk into poverty.

Feeding the World

Agribusiness justifies intensive farming on the grounds that only in this way can farmers grow enough food to alleviate world hunger—but this, as we shall see, has by no means been proved, and is hotly disputed by many. And anyway, it is not only to feed the hungry, this relentless determination to grow more and more crops, never mind the consequences. Industrial agriculture cultivates plants for many purposes other than food, such as timber, clothing, and biofuel. And only too often, as agribusiness spreads its grasp over more and more land worldwide, it is the economic interests of individuals, institutions, and governments that drive such projects, ruthlessly eliminating the small farmers and peasants, taking over their land.

Although some peasant farmers may find a better life when they leave the country, I’ve known and heard of many instances where once-independent farmers end up beggars in the cities, for they do not have the skills to get a job. And there are certainly those who miss their life in the country. It’s one thing to choose to change your way of life, and another to have it forced upon you. Those who stay, paid to work on the land they once owned, are often exposed, along with their families, to harmful chemicals. People as well as the environment are the losers. Poverty and hunger are increasing, and thousands of farmers are committing suicide around the world.

The latest tool in the arsenal of modern agribusiness is the genetically modified plant, which, along with all its false promises and resulting disasters for the environment and for farmers, I shall be discussing in the next chapter.