Chapter 19

The Will to Live

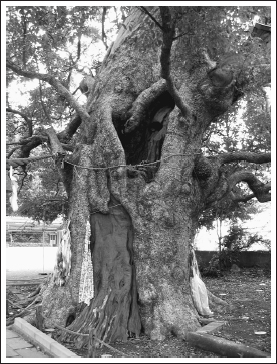

One of the two 500-year-old camphor trees that survived the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki that ended World War II. Only about half the trunk and a few leafless branches remained. It was designated a national monument in 1969. Prayers written on strips of parchment are hung from its branches in memory of the thousands of Japanese who died. (CREDIT: MEGHAN DEUTSCHER)

Well, dear reader, we have come to the end of our wandering through the wondrous Green Kingdom, the world of plants. Together we have traveled along well-trodden paths, turned aside to explore small lanes, and ventured into places hitherto unknown even to me. We have been up in the strange world of the rain forest canopy to meet life-forms that never leave the trees, and delved into the eerie world under the ground, where roots and fungi live their fascinating connubial lives.

We have traced the origins of some of the garden plants that we love today, and investigated those plants that have medicinal qualities, as well as those that, when treated and used unwisely, can harm us.

We have learned a little about the long-ago days when nations established colonies overseas and shackled slaves in order to make their masters prosper, and we have been shocked by the harm that agriculture has wrought on humans and the environment alike by those who think only of making money and care not for the future of the planet—or, it seems, of their children.

We have stared aghast at the harm that our species has, for centuries, inflicted on the natural world, and been stirred by the actions of those brave green warriors, standing up to the might of ruthless governments and corporations.

These explorations have been dictated by my own travels, have happened because of the people I met who told me wondrous tales or as the result of one of those Internet sessions where one thing led to another to another, until I ended up in places I never knew existed and was so inspired I had to call or e-mail those who were connected to the amazing stories I found.

I am fortunate. I have spent time in wild places where people live in harmony with nature, taking from the land around them only as much as they need. Places where trees and plants are not just valued for the food, healing, and clothing they provide but are also truly appreciated and respected. And where they grow freely, expressing their plant natures fully and magnificently. I have also spent time among the tortured plants, plants with limbs cut and twisted into growth patterns dictated by their human masters, neglected in little office pots, sickened by applications of agricultural chemicals, lined up along busy city streets where they are exposed to all the pollution of the passing cars. Yet still they do their best, absorbing CO2 from the contaminated air, drawing sunlight through leaves coated with grime or poisons, producing oxygen for the rest of us. And, so often, brightening our day with flowers.

Indeed, nature is resilient. Therein lies our hope. And I want to end this book with three of the most extraordinary stories of survival that I have come across. They all concern trees. After all, trees were my first love.

The Grandmother Tree Who Refused to Die

Every time a particular species of tree becomes extinct, the distinctive murmuring of its leaves in the wind is lost forever. Fortunately we are waking up to the situation, and there are people and organizations working to save species after species. This first story is about a most singular tree. It describes the persistence and tenacity of people who worked and never gave up, determined that this one tree and its lineage should be saved so that the impossible would come to pass.

Cooke’s koki‘o (Kokia cookei) is a Hawaiian tree that was “discovered” in the 1860s by Mr. R. Meyer on the small archipelago island of Molokai. Though he searched everywhere, he found only three individuals of this charming new species, with its delicate star-shaped leaves. Several years later, when botanists went back there, they failed to find even one, and it was assumed that Cooke’s koki‘o was extinct.

But not so—about thirty years later one tree was found in the same general area, probably the last survivor of the original trio. As I read about her, I found I was thinking of her as Grandmother Koki‘o, and that is how I introduce you to her! Five years later, when another group of botanists returned to the site, they found that Grandmother Koki‘o, although still living, was in very poor shape, and three years later she was dead. In 1918 Cooke’s koki‘o was officially listed as extinct in the wild.

However, that old tree, sick though she had been, had managed to produce a few seeds before her death. And at least one of those precious seeds must have germinated, because twelve years later, in 1930, a young tree—the offspring of Grandmother Koki‘o—was found near the site of its dead parent. It was taken to the Kauluwai residence on Molokai so that it could be better looked after, and there it took root, grew, and produced seeds. From those seeds more than 130 seedlings grew—the future of the species seemed assured.

Imagine their dismay when botanists who went to see how the seedlings were getting on found that not even one seemed to have survived. Their parent, seeded from Grandmother Koki‘o, was still living—but died in about 1950. This time, surely, Cooke’s koki‘o was finally extinct.

But there was something magical about Grandmother Koki‘o’s lineage. I can almost imagine the spirit of that original tree hanging around and breathing new life into dormant seeds. Because, almost twenty years later, in 1970, one more single adult tree was found—at the Kauluwai residence! And so, yet again, the Cooke’s koki‘o had risen, like the phoenix, from the ashes.

But that is not the end of the story! Eight years after it had been found, in 1978, that one lone survivor, grandchild of old Grandmother Koki‘o, was caught in a fire. Unable to escape, it burned. But by an amazing stroke of good fortune, before the mostly charred remains of the tree had lost all life, someone removed a still-living branch.

One branch, the last link in an unbroken lineage that stretched back over more than a hundred years to the tree’s ancestor in the Hawaiian forest. That one special branch was grafted onto a related species at the Waimea Arboretum on Oahu. And there, with expert care, the graft took. And grew. True, there was sap from a different species in its veins—but the life force, surely, was inherited from Grandmother Koki‘o.

As time went on, more and more plants from that original graft were distributed all over Hawaii. They seemed to prosper. But—and it was a very big but—not one of them set seed. For almost a quarter of a century those young trees grew without producing, between them, even one seed. Not even one.

Not until a horticulturist on Oahu finally managed to get viable seeds from one of the young koki‘os. Those seeds grew, and one of the precious seedlings—now the great-grandchild of Grandmother Koki‘o—was sent to the local Audubon center, where it grew, but reluctantly. The others died.

Alas, it was not strong, this miracle tree. How fortunate, then, that at this point Nellie Sugii, director of the Hawaiian Rare Plant Program, was asked to help save it. She was determined to succeed, for she knew the extraordinary history of its ancestry. Nellie worked with tender embryonic plants grown from seeds, trying to find a way to get more vigorous seedlings.

I asked her how she felt when given this awesome responsibility. She replied that in the beginning it was quite frightening, but thrilling at the same time. “The procedure was new, and tried only a few times,” she told me. And on those occasions the seedlings had not survived.

But although she felt apprehensive, she was excited to try. And “totally elated” when a few tiny seedlings started to turn green and began to grow. Perhaps she succeeded because she has a connection with the plants she grows.

One of the Cooke’s koki‘o seedlings nurtured by Nellie. One day, with luck, it will return to its ancestral homeland in Hawaii. (CREDIT: NELLIE SUGII)

“I watched them every day,” she told me, “and talked to them and bossed them to grow… and be strong. And they did.” She also used to play a lot of Hawaiian classical music to Grandmother Koki‘o’s great-great-grandchildren, and sometimes rock ’n’ roll. “I like to think they enjoyed it as much as I did,” she said.

It is because of Nellie’s painstaking (and ongoing) efforts and her dedication that Cooke’s koki‘o can, at long last, produce viable embryos that are germinating and producing healthy seedlings. These have been cloned, and one of them is now growing and producing fruit on the island of Molokai, the place where Grandmother Koki‘o originated, on the property of Rikki Cooke, a descendant of the family for which the tree is named.

Surviving the Atomic Bomb

This is the incredible story of three trees that survived the atomic bombs that were dropped in 1945 on the unsuspecting citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. Although the deployment of these bombs almost certainly played a major role in ending World War II, it also led to the immediate deaths of more than 100,000 innocent Japanese civilians. The contamination of the environment with radioactive materials led to the suffering and death of thousands more people for years to come. And vast areas of human habitation and the natural world were laid waste. Indeed, the creation of those bombs represented one of the most monstrous tools of war ever unleashed by the human species, and as we know only too well, the threat of nuclear war still hangs over the world today.

The first of the three survivor trees was a Gingko biloba that had been planted in 1850 as a temple tree. It survived the destruction of Hiroshima, although the temple itself was destroyed. Eventually, as life returned to the shattered city, there were plans to cut the survivor down to make way for a new temple building. But thousands protested such a heartless suggestion, and in the end the plan for the temple was reconfigured. I have not been there, but I have seen pictures that show how the steps up to the entrance pass on both sides of that tree, and seem to hold it in their embrace.

In 1990, I went to Nagasaki to give a lecture. I found the city lush and green—which startled me, as I had been looking, in dismay, at photographs taken forty-five years earlier that showed the lunar landscape that was the aftermath of the second atomic bomb.

My hosts filled me in on some of the history. Two months after the explosion, they told me, a group of scientists and military had visited Nagasaki to assess the impact of the bombs. One of them, Lieutenant R. Battersby, wrote an account of what he saw. Everything, he said, was destroyed. Trees had lost all their leaves and branches or been uprooted. Sometimes a great trunk had been snapped in half. It must have been like a scene from Dante’s Hell.

To his amazement he found two five-hundred-year-old camphor trees that were still alive. The upper part of their trunks had been ripped off, and the remainder had lost many branches and all their leaves. Once, they had been very tall trees—now, mutilated, they were only some thirty feet high.

Those two trees in Nagasaki are still living. I was taken to see one of them—it had been designated as a national monument in 1969. This survivor, like the gingko in Hiroshima, had prayers, written in tiny kanji on strips of parchment, hanging from its branches, placed there by those who will never forget. It is revered, a holy shrine and memorial to all who died and suffered. I stood there a long time, humbled, in tears.

One of my most precious possessions is a leaf from this tree, given to me by my Japanese host, a powerful symbol of nature’s resilience.

The Tree That Survived 9/11

This story comes from another dark chapter in human history. A recent horror, which all but young children will remember. A day in 2001 when the World Trade Center was attacked, when the Twin Towers fell, when the world changed forever.

I was in New York on that terrible day, traveling with my friend and JGI colleague Mary Lewis. We were staying in mid-Manhattan at the Roger Smith Hotel. First came the confused reporting from the television screen. Then another colleague arrived, white and shaken. She had been on the very last plane to land before the airport closed, and she actually saw, from the taxi, the plane crashing into the second tower.

Disbelief. Fear. Confusion. And then the city went gradually silent until all we could hear was the sound of police-car sirens and the wailing of ambulances. People disappeared from the streets. It was a ghost town, unreal. There were times when I felt I was living in a dream.

It was eight days before there was a plane on which we could leave. Eight days during which the city remained quiet and fear gave way to grief, anguish—and eventually, as the facts emerged, anger. Mary and I met with our Arab and Muslim friends, desperate to try to help them face the terrible backlash that we predicted would be directed against hundreds of innocent people. And all the while we could see the haze over what had been the Trade Center, and we could smell death.

Ironically, when Mary and I finally left, we were flying to Portland, Oregon, where I had to give a talk to a boys’ secondary school, a talk entitled “Reason for Hope.” It was, without doubt, the hardest lecture I have ever had to give. For where was hope at that time? Only when I was actually talking, looking out over all the young, bewildered faces, could I find the things to say, drawing on the terrible events of history, how they had passed, how we humans always find reserves of strength and courage to overcome that which fate throws our way.

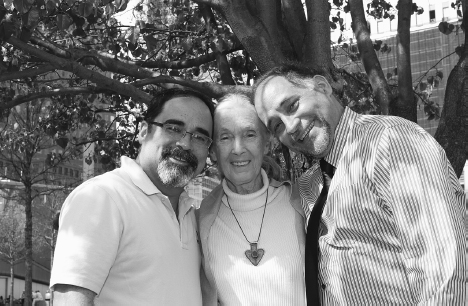

Just over ten years after 9/11, on a cool, sunny April morning in 2012, I went to meet “Survivor,” a Callery pear tree, and the three people who had most to do with her survival: Bram Gunther, Ron Vega, and Richie Cabo. We met outside the new 9/11 Memorial at what was once known as Ground Zero, and went through the tight security together. I could hardly believe that, finally, I was going to meet this incredible tree.

In the 1970s she had been placed in a planter near Building 5 of the World Trade Center, and each year her delicate white blossoms had brought a touch of spring into a world of concrete. In 2001, after the 9/11 attack, this tree, like all the other trees that had been planted there, disappeared beneath the fallen towers.

But amazingly, in October, a cleanup worker found her, smashed and pinned between blocks of cement. The discovery was reported to Bram Gunther, who was then deputy director of forestry for the NYC Parks Department, and when he arrived, he initially thought the tree was unsalvageable. She had been decapitated and the eight feet of trunk that remained were charred black, the roots were broken, and there was only one living branch.

Bram told me how, as he looked at the stricken tree, he was skeptical at first, but ultimately the cleanup workers persuaded him to give the tree a chance. And so he ordered that she be sent off to the Parks Department’s nursery in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx.

Ron Vega, now the director of design for the 9/11 Memorial site, was a cleanup worker back then. He smiled as he thought back to that time. “A lot of people thought it was a wasted effort to try to rescue her,” he recalled. “So she was taken out of the site almost clandestinely—under the cover of night.”

As we walked toward this special tree, on that special April day, I felt as much in awe as if I were going to meet one of the great spiritual leaders or shamans.

She is not spectacular to look at—not until you realize what she has been through and understand the miracle of her survival. We stood together outside the protective railing. We reached out to gently touch the ends of her branches. Many of us, perhaps all, had tears in our eyes—my own eyes were too blurred to be sure.

Richie Cabo, the nursery manager, who became one of Survivor’s principal caregivers, told me that when he first saw the decapitated tree, he did not think anything could save her. But once the dead, burned tissues had been cut away and her trimmed roots deeply planted in good, rich soil, Survivor proved him wrong.

“In time,” said Richie, “she took care of herself. We like to say she got tough from being in the Bronx!” But in the beginning, with all the fertilizing and pruning, it was hard work. And during this time all the staff became very attached to Survivor, for she symbolized endurance and resilience. In particular a special bond grew up between the tree and Richie. “She became dear to me,” he said.

In the spring of 2010 disaster struck Survivor again. Richie told me how he got news that the tree had been ripped out of the ground by the terrible storm that was raging outside. He rushed there at once with his three young children. They found the roots completely exposed, and he and the children and the other nursery staff worked together to try to rescue her.

At first they only partially lifted the tree, packing her in compost and mulch so as not to break the roots. For a long while they gently sprayed her with water to minimize the shock, hoping she’d make it. A few weeks later they set to work to get Survivor completely upright.

“Survivor,” a Callery pear, was the only tree at the World Trade Center plaza to survive 9/11. Horticulturist Richie Cabo (right) helped nurse the decapitated and mutilated tree back to health, and Ron Vega (left) made sure she had a place of honor back on the plaza of the 9/11 Memorial site in New York City. (CREDIT: MARK MAGLIO)

“It was not a simple operation,” Richie told me. “She was thirty feet tall, and it took a heavy-duty boom truck to do the job.”

But, yet again, Survivor survived.

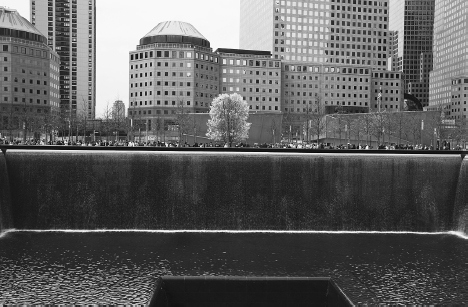

It wasn’t until six years after Ron Vega had witnessed the mangled tree being rescued from the wreckage that he heard that Survivor was still alive. Immediately he became passionate to bring her back and incorporate her into the design—and with his new position he was able to make it happen. Finally the day arrived, the day when Survivor finally came home. She was planted near the footprint of the South Tower.

It was an emotional ceremony for her planting. One of those taking part was Keating Crown, who had escaped from the seventy-eighth floor down the last usable stairwell of one of the towers. He said, in his remarks, that the survival of the tree was symbolic of the endurance of the human spirit.

There was a lot expressed that day. “For my personal accomplishments,” Ron said, “today is it. I could crawl into this little bed and die right there. That’s it. I’m done… To give this tree a chance to be part of this memorial, c’mon, it doesn’t get any better than that.”

As Survivor stood proudly upright in her new home, a reporter said to Richie, “This must be an extra-special day for you, considering it’s the ten-year anniversary of the day you were shot.”

Before he started working at the Bronx nursery in the spring of 2001, Richie had been a corrections officer at Green Haven, a maximum-security prison in New York. He had left the job after nearly dying from a terrible gunshot wound in the stomach, inflicted not at the prison but out on the streets when he tried to stop a robbery in progress.

Until the reporter pointed it out, Richie hadn’t even realized the date was the same, and then, he told me, he couldn’t even speak for a moment. “I could hardly even breathe,” he said. And he thought it was probably more than a coincidence that the tree would go home on that special day. “We are both survivors,” he said. “We healed together. And somehow it seemed only fitting.”

“Survivor” before (above) and after (next page). The first picture was taken just after the terrorist attacks. The next one was taken ten years later. She is a testament to the resilience of nature and the ability of humans to help if they will only understand how important it is. (CREDIT: MICHAEL BROWNE)

While overseeing the design, Ron had made sure that the tree was planted in such a way that the traumatized side faces the public. One of the branches was low-hanging, and Ron said ordinarily they would have removed it, but instead they simply raised it slightly with a support cable so that people wouldn’t bump into it. “It took ten years for her to grow that branch, so there is no way we would lop it off.” He stroked the branch lovingly as he spoke.

(CREDIT: PHOTO BY AMY DREHER, COURTESY 9/11 MEMORIAL)

Some people, Ron told us, weren’t pleased to have the tree back, saying that she “spoiled” the symmetry of the landscaping, as she is a different species from the other nearby trees. Indeed, she is different. For one thing she is much older, and wiser. And on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, when the memorial site was opened to survivors and family members, very many of them tied blue ribbons onto Survivor’s branches.

One last memory. Survivor should have been in full bloom in April when I met her. But, like so many trees in this time of climate change, she had flowered about two weeks early. Just before we left, as I walked around this brave tree one last time, I suddenly saw a tiny cluster of white flowers. Just three of them. Somehow it was like a message symbolizing, for me, the power of the life force that had enabled Survivor to be brought back into the world.

It reminds me of the ancient Miharu Takizakura cherry tree near Fukushima, in Japan, said to be one thousand years old. That tree has survived many wars, many storms and hard winters, and she is much loved. Once, after a heavy snowfall bowed her branches to the ground, the local people saved her by freeing the branches of snow and then supporting them with stakes. This tree survived the devastating 2011 earthquake and tsunami as well as the Fukushima nuclear power plant explosion.

And when she flowered the next spring, a delegation from the town, including children, took some of her seeds to Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank, in gratitude for British aid after the disasters. That gift not only demonstrated their high regard for that so-special tree but also ensures that her lineage will survive long into the future.