5 OFF THE BIKE TRAINING

OFF THE BIKE TRAINING WILL HELP TO MAKE YOU A MORE ROUNDED AND INJURY-RESILIENT CYCLIST, AS WELL AS BOOSTING YOUR PERFORMANCE AND MAKING YOU MORE COMFORTABLE ON THE BIKE.

‘Training can be monotonous, and it is hard work, but you never lose sight of why you’re doing it. Every single effort of every single session counts in the months and years leading up to a big event.’

SIR CHRIS HOY, ELEVEN-TIME WORLD CHAMPION AND SIX-TIME OLYMPIC CHAMPION

ONE OF THE FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES of training is specificity. This simply states that the best training for a given activity is performing that activity. So, the best training for cycling is, unsurprisingly, getting out and turning those pedals over. It may seem contradictory, therefore, especially if the time that you can devote to training is limited, to suggest that you devote some of it to off the bike training.

The ‘only worthwhile training for cycling is cycling’ mindset prevailed within the sport until very recently and even now, within less progressive professional teams, the benefit of off the bike training is viewed with scepticism. Not so long ago the only ‘cross training’ that riders would do might be some cross-country skiing at the off-season get-together training camp. The shift in mindset embracing off the bike training was due in no small part to the work of the Great Britain Cycling Team in the build-ups to the Beijing and London Olympics.

Strength training had been an accepted component of track sprinters’ training for years. In fact, they’re often jokingly referred to as weightlifters who occasionally ride bikes. With certain track endurance disciplines, specifically the Team Pursuit, evolving to demand more sprint-type performance, the coaches started to prescribe more gym work for the endurance riders. The results were good and the riders started to notice improvements in others areas of their riding too, including on the road. The riders and coaches took this knowledge to their pro road teams, and slowly it became an accepted part of the training routine for most road cyclists.

One of the biggest changes in the way pro cyclists train has been the inclusion of focused off the bike training.

‘I’d always do some gym work as I came off my post season break in October or November through to when I started racing in February. It’d always hurt like hell for the first few weeks but it definitely helped and made me stronger on the bike. I’d work with a personal trainer to ensure I was doing it right and, as the season drew nearer, I’d focus more on explosive plyometric type work to improve my sprint.’

DEAN DOWNING, EX-PRO, FORMER BRITISH CIRCUIT RACE CHAMPION AND NOW COACH

‘Over the years I’ve focused a lot more on off the bike training. I’ve noticed that it has benefitted my stability, strength and explosive power on the bike. I’ll do other activities sometimes, such as occasionally go for a run or do some paddle boarding, that’s my idea of cross training, but the gym work is the important stuff.

TIFFANY CROMWELL, CANYON/SRAM

Off the bike training, if done correctly, can be directly beneficial to your cycling. It can improve your peak power production and make you more stable and efficient when pedalling. It can help you to hold a more aerodynamic position and generally be more comfortable on the bike.

Almost more important, though, are the indirect benefits. Cycling, although a brilliant form of exercise, works your body in very limited and fixed patterns. This means that, although you can be incredibly strong on the bike, if you’re challenged outside of these confines you expose yourself to injury risk. Whether it’s gardening, lifting the shopping or your children out of the car or some DIY, a loading pattern that you’re not used to can easily cause injury and result in time off the bike. Additionally, the biomechanical issues that arise from the amount of time we spend seated in modern life, whether working at a desk or driving, for example, are compounded by the hunched-over flexed position that cycling involves. The resulting tight hip flexors, stiff lower back and poorly functioning glutes can manifest in a number of problems both on and off the bike.

Former Great Britain Cycling Team lead physiotherapist Phil Burt talks about overall physical condition being analogous to a pyramid. Your specific cycling fitness forms the top tiers and capstone of the pyramid. The lower tiers and the base are represented by your all-round and general conditioning level. You should aim to make this base as broad as possible as your cycling fitness will then be built on solid foundations. If your base is narrow or non-existent, no matter how good your cycling fitness, it’s unstable and likely to break down. One of the best ways to build that broad base is to include a variety of off the bike training in your programme.

Strength work

Many cycling training manuals would at this stage recommend a gym-based cycling-specific strength routine. It would probably include squats, leg presses and an assortment of upper body and ‘core’ exercises. However, having worked with experts such as Phil Burt and Martin Evans, former head of conditioning with the Great Britain Cycling Team, I feel that this one-size-fits-all approach is at best ineffective and, at worst, possibly dangerous. With restricted movement patterns resulting from everyday life and time on the bike, complex movements such as squats and deadlifts are inappropriate for the majority of endurance-focused cyclists. Lacking sufficient strength, range of movement and control, correct form is practically impossible. If you start adding load to poor form, it is almost guaranteed to lead to problems.

Off the bike training can improve your cycling and make you more resistant to injury.

The construction and implementation of a cycling-specific strength routine should be highly individualistic and, as such, is beyond the remit of this book. I would strongly recommend Strength and Conditioning for Cyclists by Phil Burt and Martin Evans. Through an assessment based on the one used by the Great Britain Cycling Team, your weaknesses are identified and the optimum exercises to correct them recommended.

It’s a process that I’ve been through and highly recommend following. Even Olympic gold medal winners have to go through it on a regular basis. One of the basic tests is an active straight leg raise, which assesses hamstring, hip and lower back mobility. Sprinter Callum Skinner has to undertake and pass this test before every lifting session in the gym. If he fails the test, he has a series of mobilisation exercises, similar to those described below, to perform to get him through it and ready to lift. The support team know that if he attempts to lift without doing this, it significantly increases his injury risk and reduces the effectiveness of the workout. If, on any given day, the mobility exercises fail to give him a pass, maybe due to having worked particularly hard the day before, his training will be modified to accommodate this.

At the very least, if you’re wanting to embark on a strength block, you should consult with a qualified fitness or health professional. You should explain your cycling goals to them and they should be able to help you to construct a suitable routine and demonstrate good technique.

‘Off the bike training is really important as it’s an unnatural and extremely demanding task for the body to sit on the bike for hours. During the training camp in December we analyse and assess all the riders to determine their weaknesses and what needs working on. We’ll then give them exercises to do and a plan to follow.’

JULIA SCHULZE, TEAM DOCTOR, CANYON/SRAM

Scheduling in strength work

If you already have a strength routine that you’re happy with and are confident in your form and technique or are working with a qualified fitness professional, the best time to work on building strength is during the early off season. You won’t be looking to perform very high-intensity sessions on the bike and therefore the additional fatigue from lifting can be accommodated. I would recommend scheduling in your strength sessions on the days following your midweek workouts or, if you’re able to do a split day, do the bike session in the morning and the gym in the evening. This will allow for maximum recovery after the strength work so that the impact on the quality of your riding is minimal. Examples of how to schedule strength work into your training are given below. As you can see, to fit in three strength sessions a week, split days are your only real option.

The off-season is usually the best time to schedule in some focused strength training.

To make gains, you should be looking to lift 2–3 times each week during your first early off season 8–12-week training block. As you move into late off season and pre-season, you should drop the number of strength sessions to 1–2 each week, with more of a focus on maintenance rather than progress. Be sure to monitor the impact it’s having on your cycling workouts and, if necessary, back off the strength work more. During the season or in the run-up to an important event, you should probably be looking to drop to a single maintenance session each week or to remove the strength work completely from your routine.

OFF SEASON X2 STRENGTH SESSIONS PER WEEK

| Monday | Big Gear/Low Cadence |

| Tuesday | Strength |

| Wednesday | Rest |

| Thursday | Big gear/low cadence |

| Friday | Strength |

| Saturday | Endurance ride |

| Sunday | Rest |

OFF SEASON X3 STRENGTH SESSIONS PER WEEK USING SPLIT DAYS

| AM | PM | |

| Monday | Rest | Rest |

| Tuesday | Big gear/low cadence | Strength |

| Wednesday | Rest | Rest |

| Thursday | Big gear/low cadence | Strength |

| Friday | Rest | Rest |

| Saturday | Strength | Rest |

| Sunday | Endurance ride |

The myth of low weight/high rep for endurance

One of the most common mistakes that cyclists make when strength training is to think that, as they’re endurance athletes, they should be lifting low weights for a high number of reps. They believe that sets of 20–50 reps best mimic the demands of cycling and so will result in the most transferable gains. Unfortunately, this is incorrect as even riding for as little as 30 minutes at an average cadence of 90 rpm will involve 2,700 pedal rotations. Even 3–5 sets of high rep lifting will come nowhere close to this number, so the idea of it mimicking the activity just doesn’t tally. Also, for developing strength, high reps and low weight are practically useless. Lower rep ranges, typically 6–10 reps using appropriate load, are far more effective and beneficial.

Some riders also avoid lifting heavier weights because they’re concerned about developing unnecessary bulk. This isn’t a problem, as even bodybuilders who are lifting and eating with the sole intention of gaining bulk often struggle, unless unusually genetically blessed, to gain significant mass. Additionally, as you’ll be combining strength work with cycling, known as concurrent training, this severely limits the potential for significant muscle growth.

Mobility work

One of the main requirements for having that broad base of conditioning is good mobility and flexibility beyond that required by cycling alone. Many riders are aware of stretching and maybe do some token stretches after a ride but it’s normally fairly unfocused and without structure. Similarly, a lot of cyclists will occasionally dig out a foam roller but often only when feeling stiff or sore.

Mobility work combines tool-assisted self manual therapy (TASMT), using a foam roller or trigger ball to release an area, with stretching to work it through an extended range of motion. Almost all cyclists would benefit from focused mobility work throughout the year. It will help to address imbalances and tightness both from cycling and from daily life. It can improve your comfort and position on the bike and increase your resilience to injury from movements and activities outside of cycling.

Unlike strength training, mobility work will not have an acute negative impact on subsequent cycling workouts. In fact, you will probably find it makes you feel better on the bike. This means that you can schedule in mobility work at any time, even daily and on ‘rest days’, throughout the entire cycling year.

The routine suggested below takes just over 30 minutes to complete and covers most of the classic areas where both cycling and ‘desk time’ can cause problems. The more you can do of this type of work the better, really, but you should aim at the minimum for 2–3 focused bouts each week. You will probably find certain pairs of exercises feel tougher and that may indicate an area that needs working on. There’s no reason why you can’t work on certain movements daily or even multiple times per day.

Restorative off the bike work, such as mobility training, yoga and Pilates, should be a staple throughout the year.

The advice always given previously for traditional stretching routines was immediately post-exercise. However, the last thing you want to do when you come in cold and wet from a long hard ride or dripping with sweat from a gruelling session on the turbo is roll around on a mat. It’s uncomfortable and you’re unlikely to do a decent job. You’re better off getting clean, warm and fed, and then dedicating some quality time to mobility work. In fact, you can work on this routine at any time, even in front of the television in the evening. My preference tends to be first thing in the morning a few times a week for the full routine and then ‘as and when’ working on particular exercises when I feel I need them.

You’ll need to purchase a foam roller. The hollow ones are really good as they’re light for travelling and you can pack gear inside them. You’ll also need a trigger point ball. You don’t need anything special – a hockey ball or a firm rubber dog ball are both perfect.

The A) exercise is always TASMT.

•Whether using the foam roller or trigger point ball, don’t just roll backwards and forwards. Explore the area you’re working on, shift your body weight around to change the emphasis and, when you find tight spots, oscillate over them until they release.

•Spend at least 2 minutes on each area or side before moving on.

The B) exercise is always a stretching movement.

•Move and develop the stretch, don’t just hold it passively.

•Once you find the limit of your movement or a tight area, breathe deeply and try to work through it.

•Hold and develop each stretch for 2 minutes.

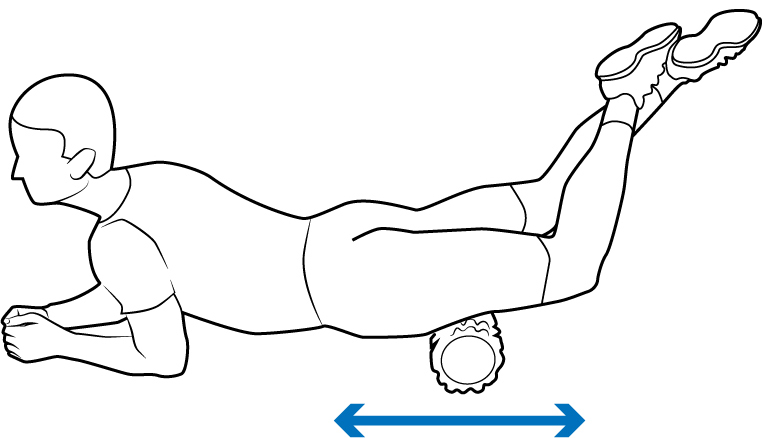

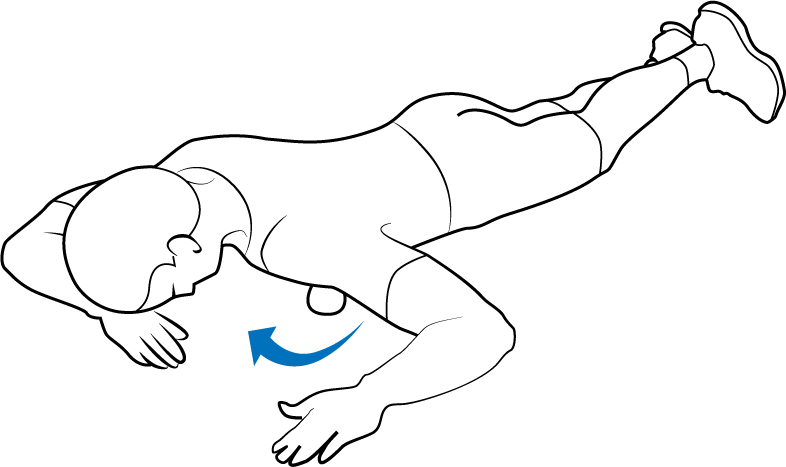

1A) QUAD FOAM ROLL

This muscle group at the front of your thighs consists of four muscles: the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis and sartorius. The rectus femoris especially is responsible for driving your pedals around but, if allowed to become too tight, can have an adverse effect on both posture and biomechanics, resulting in lower back pain and, potentially, hip and knee problems.

•Lie face down in a front plank position with one thigh on the roller.

•Bend the knee of the leg being rolled and hook it behind the ankle of the other leg to hold it in position.

•Roll up and down the full length of your thigh from the top of your hips to just above your knee.

•Rotate your body from side to side to focus more on the inner and outer thigh.

•Repeat with the other leg.

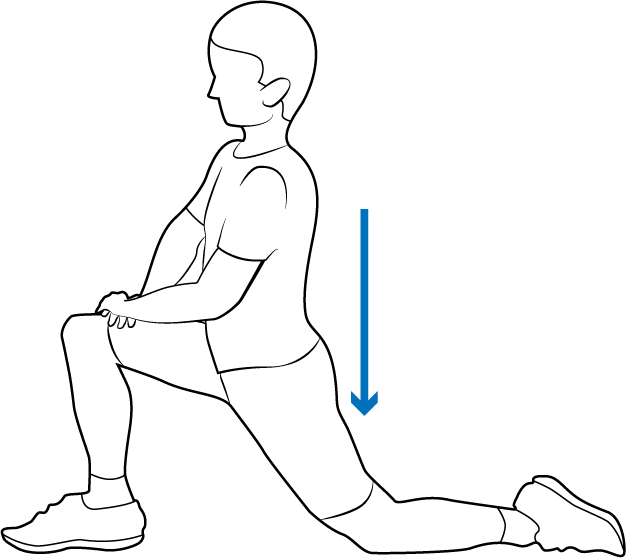

1B) KNEELING HIP FLEXOR STRETCH

•From a kneeling position, bring your right leg forward so that you’re in a kneeling lunge. You may find it more comfortable if your left knee is on a towel or mat.

•Make sure your right knee is directly over the right ankle and that your upper body is tall with your centre of gravity over your kneeling left knee.

•Contract your trunk muscles without arching your back, squeeze your glutes and lean forward, increasing the flexion of your right leg and creating a stretch on your left hip and thigh.

•Allow the stretch to develop and intensify it by moving further forwards or by trying it with the rear leg elevated.

•Repeat with the other leg.

Consistency is the key with mobility work. 5 minutes every day is better than an hour every now and then.

2A) GLUTE TRIGGER POINT BALL

When functioning properly, the muscles in your backside should play a significant role in an even and powerful pedal stroke. However, for many cyclists, poorly firing glutes due to tightness means less power and more load placed on your already overworked quads.

•In a seated position, with your hands providing support behind, place the ball under one of your buttocks.

•Cross the leg of that side so that its ankle is on the knee of the other leg.

•Tilt your body weight slightly towards the side you’re working on.

•Work over the entire buttock, rolling the ball about and shifting your body weight.

•Repeat on the other side.

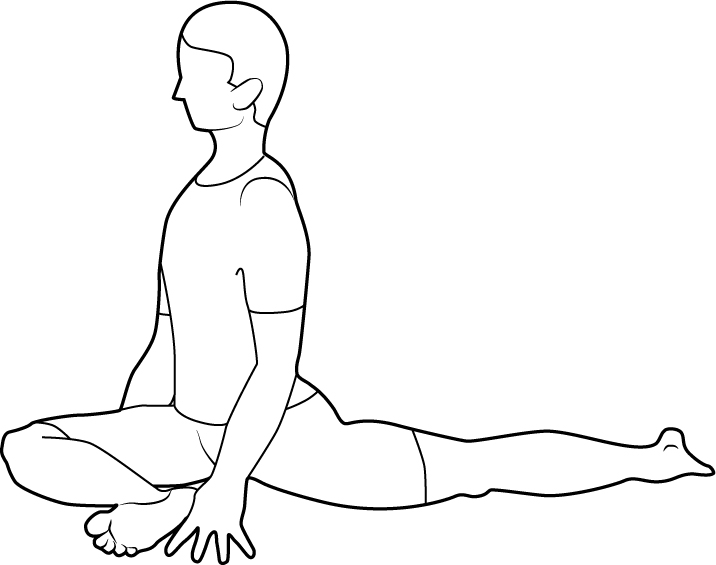

2B) PIGEON POSE

•Kneel on all fours and then bring your right leg through, placing it flat on the floor between your hands, with a 90-degree bend at the knee.

•Extend your left leg out behind you, rotating your knee so that your knee and toes are on the floor.

•Sit back into the stretch, aiming for a straight and level pelvis. Your navel should be in line with the inside of your left thigh.

•Lift your chest up and breathe through the stretch.

•Experiment with dropping your chest down towards the floor and, adding more rotation, gently work back and forth through any restrictions.

•Change sides.

‘Functional strength training for the legs is also important to help prevent injuries and to build muscle mass. It’s more of an off-season focus though as, because it’s very demanding and exhausting, it’s hard to schedule into the in season without having a detrimental effect on race performance. For this reason, general mobility work and trunk strengthening is better throughout the year.’

ANDREAS LANG, TEAM PHYSIOLOGIST, CANYON/SRAM

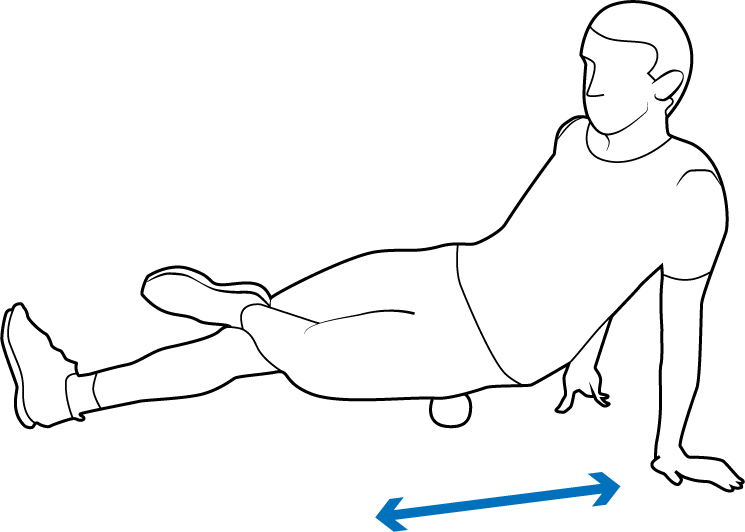

3A) HAMSTRING FOAM ROLLER

Sitting on a bike or at a desk or driving can cause the hamstrings to tighten. This can make holding an aero position on the bike difficult and is one of the most common causes of lower back pain on the bike.

•In a seated position, with your hands behind you for support, position either a foam roller or a trigger point ball under the mid-point of the back of your thigh.

•Cross one ankle over the other to focus all your weight on one leg.

•Roll up and down, rotating your body to hit the inner and outer thigh and reposition the ball or roller as necessary.

•Change sides and work on the other hamstring.

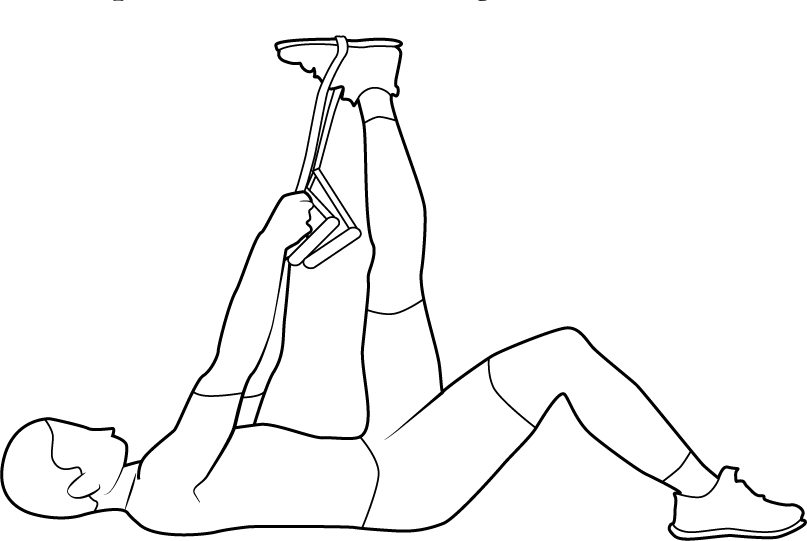

3B) LYING HAMSTRING STRETCH

•Lie on your back and loop a strap or towel around your left foot.

•Bring your knee towards your chest.

•Apply tension to your hamstring by straightening your knee. Increase the intensity by bending and straightening your leg.

•Repeat with the other leg.

4A) PEC TRIGGER BALL

With the hunched-over posture associated with cycling and keyboard work, tightness through the chest can easily develop. This can result in rounded shoulders and knock-on problems with your neck. By relaxing your chest muscles, you’ll bring your shoulders back and relax your thoracic region.

•Lying on your front, position the trigger point ball so that it’s nestled below your collar bone in the soft tissue between your shoulder and breast bone.

•Bend the arm on that side to 90 degrees. Have your other arm straight by your side or bent with your hand under your forehead.

•Rotate your head to look in the other direction and rest it on the mat.

•Gently extend the bent arm and return it to the bent position, pausing and working on any tight areas.

•Repeat on the other side.

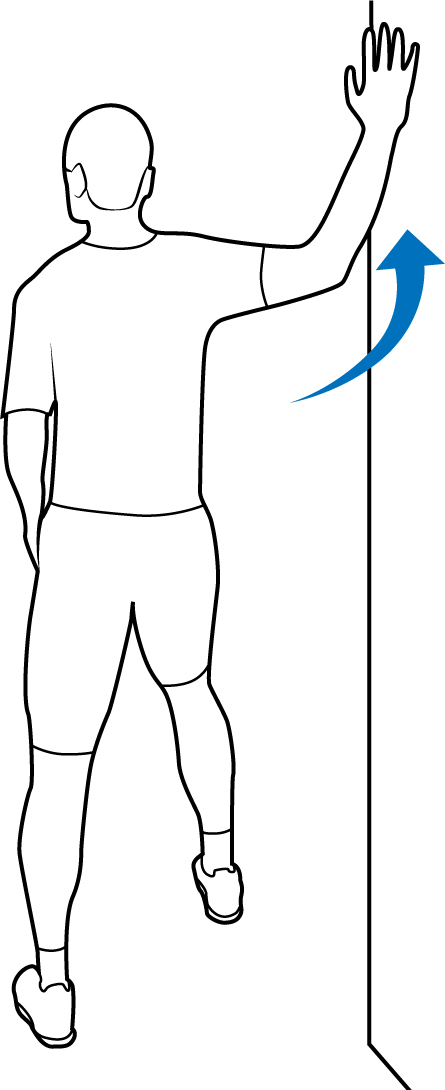

4B) PEC STRETCH

•Stand in a doorway and, with your arm bent to 90 degrees, place your forearm against the frame.

•Develop a stretch across your chest by leaning into the frame and rotating away from it.

•Repeat on the other side.

CIRCUIT CLASSES AND CROSS-FIT

Circuit classes, boot camp and Cross-Fit can offer a motivating and convenient option for riders looking to incorporate some off the bike training into their routine, but although there’s no doubt that group classes can be good for pushing yourself, they should be approached with caution. Often form and proper technique are neglected in favour of forcing out a few more reps and, with a high number of participants for the instructor to supervise, little coaching or correction can be given. It’s unlikely that the class will be cycling specific and although there might be some injury/exercise history screening beforehand, the class won’t be tailored or significantly modified to your needs. Finally, classes of this nature tend to err on the side of low weight and high reps and, as previously discussed, the benefit of this is questionable.

Yoga and Pilates

Both yoga and Pilates can be excellent complementary activities to cycling, developing both mobility and functional strength. Performed well under good instruction, they can both definitely contribute to that broad conditioning base and are ideal activities throughout the cycling year.

There are many forms of yoga: Bikram in a heated studio, the very gentle hatha and the extremely demanding ashtanga, to name a few. You may even be able to find a class specifically aimed at cyclists. As with all classes, quality of instruction is key and, with yoga, even the smallest adjustments can make a huge difference to the quality, intensity and effectiveness of a pose. It’s worth looking for some smaller classes at a dedicated yoga centre or even investing in some initial one-to-one instruction. Talk to the instructor about your cycling and they should be able to recommend specific poses or sequences that will be beneficial to you. You may have to try a number of classes and styles before you find one that suits, but it’s definitely worth persevering. Like the mobility routine, yoga is an off the bike activity that you can work on throughout the year without having to worry about any acute detrimental effects on the quality of your training on the bike. It’s also good for developing breathing control and some riders swear that this transfers over to their riding.

Pilates is named after its founder, Joseph Pilates, who originally developed it while in an internment camp during the First World War as a holistic exercise system for mind and body. Since then it became popular firstly with dancers, who used it for rehabilitation from injury, and then with the wider exercising public. Like yoga, if you find the right class and instructor, it can be brilliant for developing both mobility and strength and is an excellent complementary activity to cycling. You should try to find a dedicated Pilates centre and, if possible, find a small class using reformers. These are the wooden-framed devices that utilise springs to provide resistance to the movements you perform. Working on one of these with a knowledgeable instructor is a million miles from a mat-based ‘Pilates class’ at your local leisure centre.

Running

For many cyclists, running is a dirty word, but it can be a useful cross-training option. If you only have a spare half hour at lunchtime, the weather makes cycling unsafe or you are travelling without your bike, popping on a pair of running shoes can be a time-effective way of keeping your fitness topped up. Minute for minute, it also tends to burn more calories than cycling so if weight loss is a priority for you, it can be a good choice. However, especially if you’re not used to it, it can be extremely fatiguing for your legs and has to be carefully scheduled so as not to impact negatively on your cycling sessions. As with strength training, the best time of year for running is during the off season when your cycling sessions aren’t so demanding. Schedule any running into your training week to allow maximum recovery between it and your next cycling session.

Yoga and Pilates can both be excellent complementary activities to cycling.

You should try if possible to run off-road rather than pounding tarmac. It’s not so much the impact that you’re trying to avoid but the extremely repetitive foot strikes that road running entails. Off-road, every foot strike will be different and, because you’re having to focus on avoiding roots, rocks and the like, your running form will tend to be better too. Fartlek, Swedish for ‘speed play’, is a form of unstructured interval training that can work well and provide variety of intensity when running on the trails. In its purest form, you run hard when you feel strong, back off to recover and then go again. You can, however, use landmarks (such as a certain tree) to sprint to, or say you’re going to attack every hill, or even work on a minute on/minute off principle. What you’re looking for, though, is to mix up the pace and avoid mindless plodding. Be sure to spend at least 10 minutes warming up with steady jogging and then the same at the end of the session as a cool-down, with a couple of minutes of walking to finish.

It’s no coincidence that a number of top cyclo-cross racers in the UK, including Nick Craig and Rob Jebb, are also highly accomplished fell runners. Cyclo-cross obviously involves some running and the steep climbs and descents involved in fell running provide a brilliant crossover for the high intensity stop-go nature of cyclo-cross racing. Cyclo-cross legend Niels Albert includes at least one running workout in his training throughout most of the season. It’s very sprint focused, mimicking the short run-ups typically found on a cross course, and, so as not to cause too much fatigue and muscle damage, never more than 30 minutes in length.

Swimming

Swimming can be the perfect ‘recovery day’ activity, involving zero impact on your legs and with the pressure of the water actually having therapeutic recovery benefits. Australian pro Richie Porte came from a swimming and triathlon background, and still includes significant swim work in his training schedule during the off season. He’s especially convinced of the benefits on his breathing capacity. There’s no reason, if you enjoy a swim, that it can’t be part of your routine throughout the year. It shouldn’t have any negative effects on your cycling training and therefore shouldn’t present any scheduling issues.

Rowing

Another great cross-training activity for cyclists is rowing and it’s no coincidence that a number of former rowers, Rebecca Romero for Great Britain and Cameron Wurf for Australia being two, have succeeded as cyclists both on the track and on the road. Also, Sir Bradley Wiggins is currently dabbling with going the other way, from cycling to rowing. Both activities are non-impact and, for cyclists, the recruitment of the upper body means it’s excellent for developing better all-round conditioning. It’s also very good for warming up the entire body prior to any strength work.

How to improve your cycling performance

Build a broad base

Although there are proven direct benefits of off the bike training for your cycling, the main reason for doing it is to develop a broad base of conditioning and make yourself more robust and less susceptible to injury. Both cycling and everyday life, especially time spent seated, can cause postural issues and imbalances, and countering these should be a priority. It’s worth investing some time in off the bike training for this reason and to reduce the likelihood of enforced time off the bike due to injury.

Strength work

Strength work in the gym can be brilliant for cyclists but should be approached with caution. It has to be personalised and ideally supervised, at least initially, by a qualified professional. Focused strength work should be scheduled during the early off season when its impact on cycling workouts will be minimal. As you move into the pre-season and season, strength training should be reduced to a maintenance level or removed from the training plan entirely.

Mobility work

Combining tool-assisted self manual therapy (TASMT) and more traditional stretching techniques, mobility work is a must-do for all cyclists. Rather than being viewed as a post-cycling bolt-on, often given only token attention, a mobility routine should be a stand-alone part of your regular training. It can be done throughout the year and will have no negative effect on your cycling training. You’ll probably find, in fact, that it improves your comfort, position and performance on the bike, and makes you feel less stiff and sore off it.

Other activities

Top of the list of beneficial cross training activities for the majority of cyclists are yoga and Pilates. If you don’t have the discipline or self-motivation for mobility work at home, both of these are potentially ideal alternatives. Take the time to find the right class and instructor and even invest in some one-to-one tuition. Don’t be scared of running, it can be a highly time-effective cross-training activity. However, get off-road and onto the trails, mix up your pace and be wary of the effect it can have on subsequent cycling sessions. Hitting the pool is great as a ‘recovery activity’ and might have benefits for your breathing capacity. Rowers seem to make great cyclists so, it can be a great option at the gym if you want a change from the bike.

Don’t just ride your bike. Include off the bike training to make you a more rounded and robust athlete