“Let There Be Light.”

—Genesis, I, 3

“Let There Be More Light.”

— Pink Floyd , A Sauceful of Secrets

The association of Dionysos with nocturnal dances and blazing torches is a persistent motif of Athenian drama.1 The god is born by the fire of Zeus’ lightning that strikes his mother, Semele.2 Dionysos is described as ‘holding up the blazing flame of the pine-torch, like the smoke of Syrian frankincense and rushing with the fennel rod,’ ‘as leaping on the Delphic rocks with pine-torches over the twin-peaked plateau, brandishing and shaking the bacchic branch,’ and as ‘swiftly leaping onwards among his frenzied followers with flaming torch held high in the night.’3 Upon his ordering the Theban women to punish the impious Pentheus, ‘a light of holy fire towered between heaven and earth.’4 In a famous passage in the Bacchae, the chorus of barbarian Lydian maenads, released from the anxiety and the terror caused by Pentheus’ unsuccessful attempt to imprison Dionysos, sing: ‘O most radiant light for us of the joyful-crying bacchanal, how gladly I looked on you in my desolation!’5

There is no doubt that similar perceptions are anchored to ritual and mythological perceptions of the god. In later literature, like the Orphic Hymns, Oppian’s Cynegetica and Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, Dionysos is called πυρίπνοος, πυριφεγγής, πυρίπαις, πυρισθενής, πυρίσπορος, πυριτρεφής, πυρογενής and πυρόεις.6 Walter Burkert has aptly commented that ‘fire miracles are spoken of only in the Dionysos cult:7 the Thracian Crestoni had a fire-oracle of Dionysos;8 the house of the Skythian king Skyles was destroyed by lightning when he expressed his desire to be initiated into the mysteries of Dionysos.9 The maenads of Dionysos carry fire on their heads without being harmed.10 Cult epithets of Dionysos include νυκτέλιος, φαυστήριος, λαμπτήρ and his festivals, ‘held in the darkness of night amid the flickering and uncertain light of torches,’ in the eloquent phrasing of Erwin Rohde,11 are often called παννυχίς and νυκτέλια. Nocturnal rites are often associated with the cult of Dionysos, because ‘darkness possesses solemnity.’12

The aim of this chapter is to put these poetic and cultic descriptions in the context of 5th-century Athenian religion, reviewing, in the absence of what Barbara Goff has called the ‘hard’ evidence (epigraphic and archaeological data),13 the richest source of well-dated material about the Dionysian cult, Attic vase-paintings. I will not venture myself to a formal and strictly typological analysis of the available imagery, a task already undertaken in the recent book of Eva Parisinou,14 and one which frankly, I do not consider to be a particularly rewarding approach. I have chosen instead to concentrate upon a number of images displaying a rich variety of situations of torchbearing within the framework of dionysiac imagery.

Dionysos is, more than any other god, thought to be present among his worshippers, and indeed is the only god to be constantly given a retinue of mythic or mortal followers. Inevitably, then, human ritual behavior is formed following the paradigm of the god.15 Consequently, the first images in Athenian iconography in which light is connected to dionysiac ritual and myth imply the god himself.16

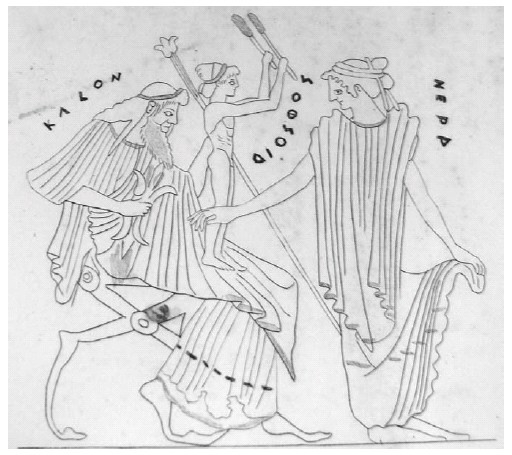

The first image of Dionysos holding torches is also the most famous and intriguing one: it appears on a small neck-amphora in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris, dating close to 500 BCE. Zeus is seated, holding a sceptre and a thunderbolt, while a boy, with two torches in his hands, stands on his knees. To the right, a woman addresses herself to the protagonists on the left, while lifting the edge of her dress (see figure 17.1).

Inscriptions accompany all the figures: besides Zeus is written KALOS, ‘beautiful.’ The boy is identified as DIOSPHOS, a word that led the German scholar Andreas Rumpf to coin the somewhat misleading name of the Diosphos Painter to identify the anonymous artist. The woman is easily identified as Hera (HERA).17

While identifying the figures as Zeus, Dionysos and Hera has never really caused any trouble,18 this has not been so regarding the interpretation of the inscriptions. The earlier discussions have been summarized by John Beazley: ‘the inscriptions can hardly be meant for nonsense … Diosphos … may be either 1) Διòς φώς, 2) δĩος φώς or 3) Διòς φῶς; these would all be unusual and poetic expressions.’19 Already in 1890, Paul Kretchmer, in a once famous, yet now largely forgotten essay entitled Dionysos und Semele, proposed the first reading, Διòς φώς, with φώς meaning ‘man.’20 This reading was widespread in the first half of the 20th century.21 The second reading, δĩος φώς (divine man), was a suggestion of Beazley himself, noting as parallel the Homeric ἰσόθεος φώς. The third reading, Διòς φω̃ς (Light of Zeus), was first advocated by Giulio Minervini, when he published the amphora back in 1850.22 Since Giovanni Becatti’s analysis of the image, in 1951, the reading ‘Light of Zeus’ is almost universally accepted, inasmuch as the god is holding torches, mistaken for thyrsi by Kretchmer but correctly identified by Minervini.23

Figure 17.1 Paris, Cabinet des Médailles 219, black-figured neck-amphora by the Diosphos painter. After Minervini 1850, p1. I.

Eva Parisinou, in a detailed presentation of the amphora in the Cabinet des Médailles, stresses the connection between the motif of the birth of Dionysos and Zeus’ lightning that struck down Semele.24 This view stems from William Furley’s account of the duality of the celebrations of Dionysos’ birth and Semele’s death.25 It would be superfluous to recite the whole body of evidence on the importance of Semele in the rituals of Dionysos. In Athens proper, an important ritual-act of the dramatic contest of the Lenaia was when the dadouchos, no doubt the homonymous Eleusinian official, holding a lighted torch, exhorted the people ‘Invoke the god,’ whereupon the whole congregation cried aloud ‘Iacchos, son of Semele, the giver of wealth.’26

The problem with this interpretation is that instead of Semele and the first birth of Dionysos from the thunder-smitten womb of his mother, the painter has presented a particular and quite unusual cultic triad, Zeus, Hera and Dionysos. But, although Dionysos and Hera are antagonists on both the mythological level, in which Hera incarnates the archetype of the wicked stepmother,27 and the cultic level (at least in Athens),28 the two divinities are virtually complementary on the symbolic level as deities who bring madness and destruction to their opponents.29 However, Dionysos and Hera betray strong cultic connections in Lesbos, where Dionysos Omestes, Zeus and Aeolian Hera formed a triad already venerated from the time of Alcaeus and Sappho.30 Alternatively, the presence of Hera may be taken as an allusion to an unknown version of the myth, where the two opponents (Dionysos and Hera) were reconciled by the formal adoption of the son by the stepmother.31

Since Otto Jahn’s passing reference to the vase in 1854, scholars are almost unanimous in considering its image as the first instance of Dionysos’ birth from Zeus’ thigh in ancient art. However, it is preferable to follow Giovanni Becatti’s opinion that the aim of the painter was not to present a narrative, but to celebrate Dionysos’ divinity and his glorious descent from the god of light.32

The archaeological context of the amphora in the Cabinet des Médailles can be reconstructed with a fair amount of confidence, thanks to an important study by Rita Benassai. The amphora was found in 1847 in a rectangular grave made up of tufa slabs (the so-called tomba a cubo type), in the SW section of the necropolis of Santa Maria di Capua in Campania. Besides the amphora, the tomb also contained a bronze dinos, used as a cinerary urn— the famous Barone lebes now in the British Museum—that stood on a tripod stand, as well as a red-figured cup by the Euergides Painter and a ram-head rhyton which has not yet been localized.33

The Barone lebes is one of the earliest and certainly the finest of the series of 25 bronze dinoi used as cinerary urns in that part of the cemetery of Capua. The lid is decorated with a group of a satyr lifting a woman and a circle of four archers in Scythian garb mounted on small horses. Exceptionally for this class of objects, incised motifs appear also as decoration on the body of the vase: figures include felines devouring their prey, Herakles with Cacus and Geryones’ cattle, a chariot-race, boxers and wrestlers.34 The iconography on the cup by the Euergides Painter is equally complex: on the tondo we see a woman playing crottala, almost certainly a maenad. The obverse shows an athlete amidst two trainers and two sphinxes and the reverse a youth leading two horses, again between sphinxes.35

According to the interesting analysis of Luca Cerchiai, the person who collected the items put in the tomb laid special emphasis on the education of young Campanians, centered upon the motifs of horse-riding, sports and archery. Cerchiai’s analysis focused on the Etruscan and Campanian reading of the image and revealed the paradigmatic nature of the figure of Herakles for the local youth.36 More recently, Natacha Lubtchansky has reinforced the connection between techne hippiké and Campanian juventus, by pointing to other dinoi from the aforementioned series with similar subjects.37 While there can be no doubt about this connection, which is supported by historical sources detailing the activity of Campanian neaniai in the cavalry (Aristodemos of Cumae being the most famous example),38 one should also note the persistent use of dionysiac motifs: a satyr and a woman on the lebes, a maenad dancing on the cup, and the infant Dionysos on the amphora; the entire Dionysiac thiasos with its ritual activities and mythic logos is put on stage here.39 So the Capuan aristocrat whose cremated remains were collected into the Barone lebes might also be regarded as a member of the local Etruscan elite which was particularly versed in dionysiac rituals. He was perhaps a mystes himself.

Mystic overtones are recurrent in Campanian versions of Dionysism. One should not forget that we are not that far in time and place from the famous graveyard of Cumae, where a group of bacchic mystai claimed the right to be buried in a separate plot, according to a famous inscription of the mid-fifth century found in 1903.40 Campanian early classical tombs a cubo contain Athenian red-figured stamnoi used as cinerary urns and representing Eleusinian and Donysiac rituals.41 Twenty years ago, Juliette de la Genière argued for a specific connection of this ritual iconography to local, dionysiac mysteries.42

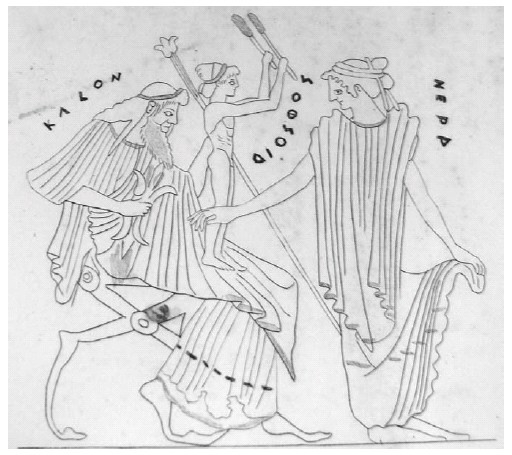

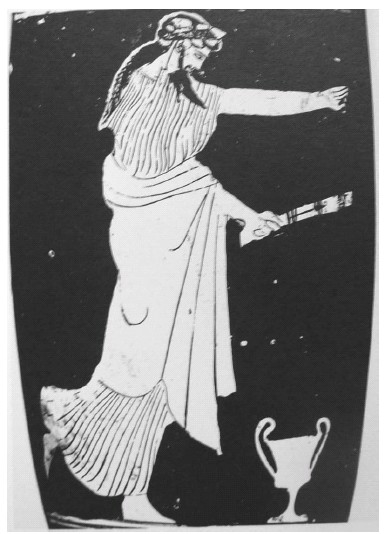

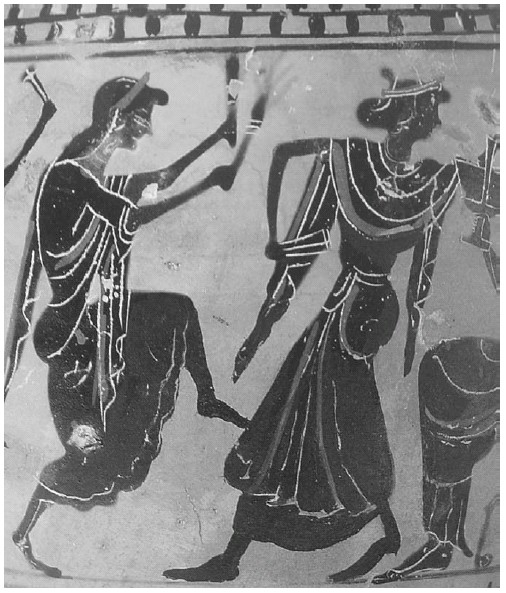

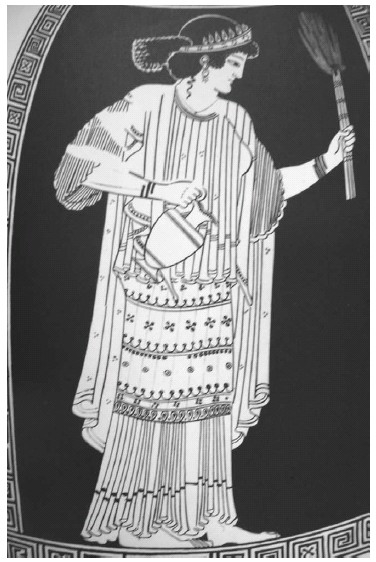

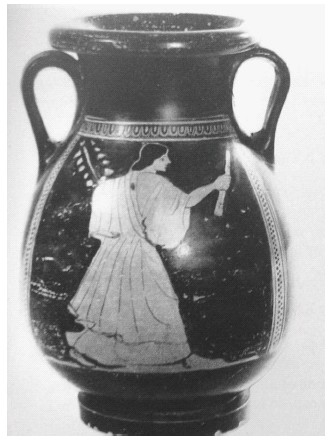

Apart from the amphora in the Cabinet des Médailles and its Campanian overtones, there is surprisingly little evidence on the iconography of Dionysos bearing one or two torches. The evidence was reviewed 70 years ago by John Beazley43 and little more can be added today, as the only secure image remains a single, very fine red-figured lekythos in Würzburg, dated to 460 BCE.44 Dionysos is dancing before a kantharos, a torch in his left hand; the inscription states that Dionysos is beautiful (KALOS) (see figure 17.2). Mystic light has already been the subject of a careful study by Richard Seaford.45 On the iconographic level, it is tempting to link mystic initiations with the image on a remarkable red-figured skyphos, once in the possession of Oskar Kokochka46 (see figure 17.3). We see a satyr in short garment, fawnskin and Thracian boots holding two torches and showing the way to a majestic woman wrapped in her mantle. The reverse bears the image of a satyr dressed in masculine garb inviting a thyrsus-bearing maenad to follow him.

Figure 17.2 Würzburg, Martin-von Wagner-Museum H 4905, red-figured lekythos. After Beazley 1939, 627, fig. 7.

Figure 17.3 Swiss, private collection, red-figured skyphos by the Lewis painter. After Kerényi 1976, fig. 97.

Erika Simon, in an essay originally published in 1963, thought that the obverse shows the escorting of the wife of the Archon Basileus, the Basilinna to the Bukoleion, were the sacred marriage with Dionysos was about to take place.47 Similar interpretations have become increasingly unfashionable today, as the majority of scholars are now moving from arbitrary ritualistic interpretations to post-modern and symbolic readings of Athenian images. Instead, the male protagonist of the scene might be regarded as a ministrant of the mystic cult of Dionysos who partly underwent a psychic transformation to a satyr via his initiation into the ritual. The logic of the construction of the image requires that the woman has not yet achieved access to the state of being entheos, of being possessed by the god.48

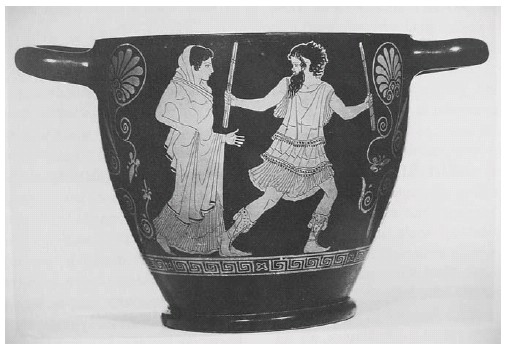

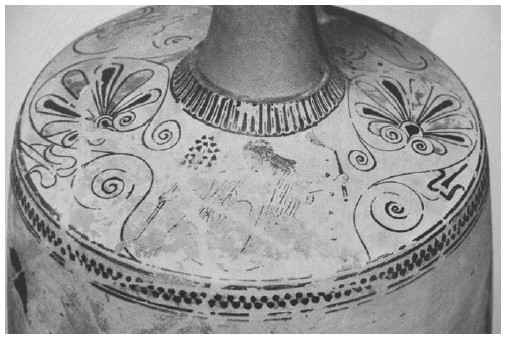

Thomas Carpenter, and more recently E. Parisinou and G. Fahlbusch, have asserted that torches first appear in ritual contexts on vases from around 460–450 BCE.49 This is a classical case of misinterpretation of the available evidence, since the image of the torch-bearing maenad appears much earlier in iconography. To my knowledge, there are at least five vases dating from the late 6th century to the first decade of the 5th century BCE, where torches are integral part 5 of a scene involving female votaries of Dionysos. The earliest vase is a black-figured lekythos in Amsterdam50 (see figure 17.4). It shows three women dancing between Dionysos who is seated and a sexually aroused satyr, who is approaching from the left. The second woman is holding two flaming torches. The context is cultic; the painter has depicted the highest moment of dionysiac ritual: the frenzied women and the satyr are experiencing the god’s epiphany. The second vase is a neck-amphora in London by the Eucharides Painter (see figure 17.5). The reverse shows a majestic woman bearing a torch and a jug about to pour wine into the kantharos held by Dionysos, who appears on the obverse.51 The third vase is another amphora by the same painter in the Louvre; it features the very popular motif of the sexual assault of a satyr on a maenad holding a torch.52 The fourth vase is a white-ground lekythos by Douris in Malibu (see figure 17.6).53 The maenad is running, a torch and a thyrsus in her hands, while looking back, as if pursued by an invisible threatening satyr. The last vase is a cup from Vulci by the Colmar Painter, showing the ‘hippy convoy’ of the Dionysiac thiasos leading the drunken smith-god, Hephaistos, who reclines on the back of an ithyphallic mule, back to Olympus. The procession is headed by a maenad with loose hair holding two torches.54 Again, this image might reflect a cultic reality, since, according to a recent interpretation, the mythical episode of ‘the return of Hephaistos is structured like the so-called epiphanic processions in honor of Dionysus at Athens, in which the god is conveyed bodily, triumphantly, into the city by his worshippers for his festival.’55 Torches disappear from the imagery of the Return of Hephaistos until about the third quarter of the century, but this disparity may in fact be due to a gap in our documentation.56

Figure 17.4 Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum 14107, black-figured lekythos. After Van de Put 2006, pl. 147.3.

Figure 17.5 London, the British Museum E279, red-figured neck-amphora by the Eucharides painter. After Beazley 1911–1912, p1. XII.

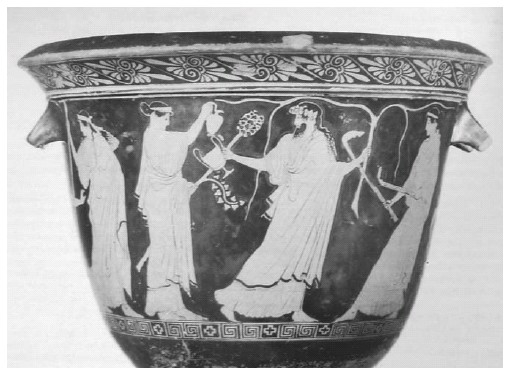

There are several hundred instances of generic dionysiac processions including satyrs and maenads holding torches. My very rapid survey has revealed the existence of more than 200 such documents, covering for the most part the second and the third quarter of the 5th century. Two motifs are most representative: that of a maenad with torch and jug, ready to serve Dionysos,57 and that of the maenad conversing with the god or with her fellow bacchants.58 Less widespread but remarkable is the motif of the maenad brandishing two torches while rushing forth (see figure 17.7).59 This image explains a passage in Euripides’ Trojan Women: Cassandra enters in a frenzied state, holding two nuptial torches and singing a parody of a nuptial song. Her attitude provokes Hecuba’s reaction: ‘give me the light; for you are not holding the torches straight, as you’re rushing like a maenad.60

Figure 17.6 Malibu, the J. P. Getty Museum, 84.AE.770, white-ground lekythos by Douris. After Kurtz 1989, 118, fig. 1e.

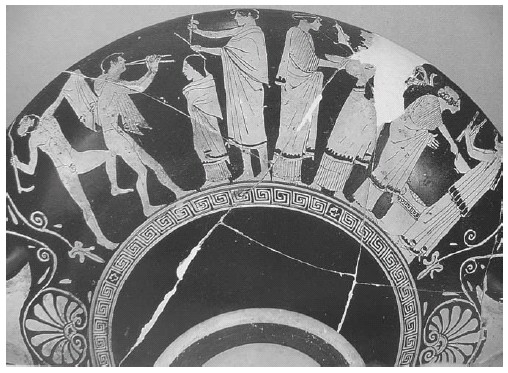

Torches appear also in iconographic contexts usually recognized as referring to the official, civic cult of Dionysos, such as a cup in Florence,61 dating from about 450 BCE. There is a semantic coherence between the three decorative surfaces of the cup, which encourages the idea of a unitary interpretation. On the medallion, Dionysos is seated, while a woman pours wine into his kantharos. On one of the exterior faces, we find a group of eight girls dancing. Finally, on the other exterior face, the painter, a follower of the Penthesileia Painter known as the Painter of Bologna 417, has represented a group of men and women involved in various cultic activities: to the left, a group of men dancing an orgiastic dance and making music, with a girl in between; to the right, a group of women bearing offerings and preparing to sacrifice on an altar. The presence of the torches in the hands of the last woman, to the right of the altar, is astonishing in the context of sacrifice. Other deviances from the normal iconography are even more notable: the sacrifice is not of the ordinary Greek bloody sacrifice, since there is no victim and the priests are all women (see figure 17.8). All these elements point to the Anthesteria; I would tentatively venture the hypothesis that the women beyond the altar to the right of the exterior belong to the college of 14 Gerarai, ‘The Venerable Ones.’62

Figure 17.7 Ferrara, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 45698, red-figured calyx-krater by the Mykonos painter. After Berti and Gasparri 1989, 28.

In any case, the festival shown on the Florence cup involves the epiphany of Dionysos, choral dances, a comos and a group of women making offerings at an altar. Shall we deduce from the presence of the torches that these complex or ritual actions take place during the night? Is there a temporal or rather a thematic sequence of the three images, as was suggested above?

We cannot give a definite response to these questions. The device of the torch is sometimes used by the vase-painters in perplexing ways. A pelike in Amsterdam63 shows on one side a woman running, holding a torch and an ivy branch (see figure 17.9). On the other side, Dionysos is depicted in a hieratic pose in front of a closed door, which may be taken as an allusion either to the gynaikonitis, or more generally to the oikos. These paintings must allude to a dionysiac ritual brought to light recently thanks to the ingenious work of Benedetto Bravo. The Italian scholar has suggested, admittedly on quite scant evidence, that during the night of the Choes, the second day of the Anthesteria, Athenian women danced in honor of Dionysos, in front of their male relatives, in a domestic setting.64 Both time and place are clearly indicated, as well as the frenzied state of the dancer, who is experiencing the epiphany of Dionysos. In other cases, however, the torches become attributes of the Dionysiac cult, without necessarily denoting specific nocturnal rites. On the socalled Lenaia vases, women are pouring wine into large jars, in front of a dionysiac idol.65 On a stamnos in Naples,66 torches are used by a maenad to the right of the idol, and by the ecstatic women dancing on the reverse. But what about the image on the reverse of a Lenaia stamnos in Boston,67 where a woman holding a parasol is included? Are we to suppose a temporal evolution, from day (parasol) to night (torches) or rather must we conclude that torch-light appears in conjunction with daylight, assuming a symbolic rather than a practical role?

Matthew Dillon wrote recently that ‘in looking at women and Dionysos on vases, it appears impossible to discern historical periods, or a change in the perception of maenads.’68 Similar statements frequently occur in the work of historians of religion, who approach the available iconographic material irrespective of its own logic of change and evolution, as if there is a stagnant and monolithic perception of ritual iconography during the whole of the classical period in Ancient Athens. Changes in the perception of dionysiac symbols are important and must be taken into account when recording the historical evolution of dionysiac rituals.69 But a warning must be sounded against the trend to equate changes in artistic currents with changes in the evolution of ritual. To give just an example, thyrsi appear in imagery around 520–515 BCE.70 Most scholars deny the status of maenad to women appearing on earlier vases, who lack the thyrsus and other paraphernalia of the dionysiac cult (fawnskins, pantherskins, ivy-branches, shaking of small animals and handling of snakes). Consequently, one might argue with Michael Edwards and Albert Henrichs, that before 520 BCE, the ritual activity that we label ‘maenadism’ was simply unknown in Attica.71 But the word thysthla, which is equivalent to the thyrsus, appears already in Homer, where, in any case, we encounter the maenad for the first time, as a ‘well-known phenomenon, so familiar in men’s minds, that the word could be used in a simile to explain the meaning of something else’72 (Andromache’s anxiety about the fate of Hector, for example).

Figure 17.8 Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 3950, red-figured cup by the painter of Bologna 417: After CVA Firenze 3, p1. 109.1.

Robin Osborne has warned against the dangers of the ‘visibility principle,’ by calling upon a statistical approach to imagery. Otherwise, the use of images to write a history of religious experience is bound to fail. Osborne’s contention is that an argument from silence (i.e., from the absence of maenadic symbols in images before the last part of the 6th century), that might be hazarded is perhaps that female worship of Dionysos was not an issue high on the agenda in Athens, at least not high on the agenda of those who painted pots.73 We might conclude in a similar manner: whether torches denote noc-turnal rituals or not, they are not regarded as essential in the visual construction of the Dionysiac experience, until about the second quarter of the 5th century, even if they already appear for some time earlier in imagery. The range of cultic activities connected to torches in dionysiac imagery is very broad: mythic and generic processions, initiations, mystic symbolism, nightlong private festivities and civic festivals.

Figure 17.9 Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum 8209. After Sotheby’s 2.12.1973, n154.

Torches must be regarded as a metaphor for the rites of Dionysos, and not as an indication of the temporal sequence of ritual.74 In other words, torches appear because they are part of the dionysiac imagery, and not because the scenery is to be located at night.75

NOTES

1. I would like to express my thanks to the organizers of the conference for the invitation. For help with the English, and various other illuminating comments, thanks are due to Dr. Christos Zapheiropoulos. Abbreviations: ABL= C. H. E. Haspels, Attic Black-Figure Lekythoi (Paris, 1936). ABV= J. D. Beazley, Attic Black-Figure Vase- Painters (Oxford, 1956). Add²= T. H. Carpenter (ed.), Beazley Addenda² (Oxford, 1989). ARV²= J. D. Beazley, Attic Red-Figured Vase-Painters² (Oxford, 1963). LIMC= Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, volumes 1–8 (Zurich, 1981–1997).

2. Eur. Ba. 1–9 and 88–93; Orph. H. 44.4–11; Paus. ix. 12, 3–4.

3. Eur. Ba. 144–48 and 306–8 respectively; Eur. Ion 714–18.

4. Eur. Ba. 1082–85.

5. Eur. Ba. 608–9.

6. Πυρίπνοος: Orph. H. 52, 3; πυριφεγγής: Orph. H. 52, 9; πυρίπαις: Opp. Cyn. 4, 287; πυρισθενής: Nonn. D. 24, 6; πυρίσπορος: Orph. H. 45, 1; πυριτρεφής: Nonn. D. 24, 13; πυρογενής: Anth. App. Ep. III 153, 3 Cougny; πυρόεις: Nonn. D. 21, 220. Cf. C. F. H. Bruchman, Epitheta Deorum quae apud poetas graecos leguntur (Leipzig, 1893), 92.

7. W. Burkert, Ancient Greek Religion, Archaic and Classical, tr. J. Raffan (Oxford, 1985), 61.

8. [Arist.] Mir. Ausc. 842 A 15–24.

9. Her. 4, 79, 1. See recently D. Braund, “Palace and polis: Dionysus, Scythia and Plutarch’s Alexander,” in The Royal Palace Institution in the First Millenium B.C. Regional Development and Cultural Interchange between East and West, Monographs of the Danish Institute of Athens, Vol. IV, ed. I. Nielsen (Athens, 2001), 21–24.

10. Eur. Ba. 757–58. See the careful discussion of J. Bremmer, “Greek Maenadism Reconsidered,” ZPE 55 (1984): 269–72.

11. E. Rohde, Psyche. The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality among the An- cient Greeks, tr. W. B. Hills (London & New York, 1925), 257.

12. Eur. Ba. 485. Nocturnal rites: Plut. Quest. Rom. 291A and Quest. Conv. 714C; Tzetzes, schol. Lyc. Alex. 212 (on Dionysos φαυστήριος); Paus. ii 7, 5 (Sicyon); Paus. vii 27, 3 (Dionysos Λαμπτήρ of Pallene); Plut. De Is. Et Os. 364F and Paus. ii. 37.6 (Lerna); Paus. ix. 9, 20, 4–21, 1 (Nyktelia Hiera in Tanagra); Paus. x 4, 3 (festival of Daidophoria); Virg. Aen. 301–3 (Cithaeron). Dionysos is called νυκτέλιος in Megara (Paus. i 40, 6) and elsewhere (Plut. De Is. E Os. 378E, Ov. Met. 4, 11). See also W. D. Furley, Studies in the Use of Fire in Ancient Greek Religion (Salem, 1981), 92–96 and 100–106.

13. B. Goff, Citizen Bacchae. Women’s Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 2004), 272.

14. E. Parisinou, The Light of the Gods. The Role of Light in Archaic and Classical Greek Cult (London, 2003), 120–23 and 221–22.

15. On this aspect of Dionysiac iconography, see C. Isler-Kerényi, Dionysos nella Grecia arcaica. Il contributo delle immagini (Pisa, and Rome, 2001), 223.

16. The same also applies to the ritual of sparagmos, the act of tearing apart small sacrificial animals in order to proceed to ritual omophagia, the eating of raw-meat: the earliest such image concerns the god himself, on a stamnos in the British Museum (E439): ARV² 298, 1643; Add² 211; LIMC 3 (1986), pl. 312, Dionysos 151.

17. Paris, Cabinet des Médailles 219: ABL 238.120; ABV 509.120; Add² 127; Parisinou (n. 14), pl. 7. The reverse shows Herakles leading the Cretan bull, in the company of Athena.

18. G. Minervini, Monumenti antichi inediti posseduti da Raffaele Barone (Napoli, 1850), 1–7, has mistaken the infant Dionysos for Artemis φωσφόρος . O. Jahn, Bes- chreibung des Vasensammlung König Ludwigs in der Pinakothek zu München (Münich, 1854), lxi, n. 402, first interpreted the scene ‘as the birth of Dionysos.’ C. Gaspari, C. and A. Veneri, “Dionysos,” in LIMC 3 (1986), 481 and 504, think that the boy might be Hephaistos rather than Dionysos. C. Reusser, Vasen für Etrurien. Ver- breitung und Funktionen Attischer Keramik im Etrurien des 6. und 5K Jahrhunderts vor Christus (Zürich, 2002), I, 164, also questioned the identification of the boy with Dionysos.

19. J. D. Beazley in ABL 96–97.

20. P. Kretchmer, “Dionysos und Semele,” in Aus der Anomia, Archäologische Beiträge Carl Robert dargebracht (Berlin, 1890), 17–29 (especially 29).

21. Accepted by O. Kern,“Dionysos,” in Paulys Real-Encyclopädie der Clas- sischen Altertumswisseschaft, Vol. 5, ed. P. Wissowa, (Stuttgart, 1903), col. 1011; A. De Ridder, Catalogue des vases peints de la Bibliothèque National (Paris, 1904), 127 and A.B. Cook, Zeus. A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. 2 (Cambridge, 1924), 273.

22. Minervini (n. 18), 1–7.

23. G. Becatti, “Rilievo con la nascita di Dionysos e aspetti mistici di Ostia pagana,” Boll. d’Arte 36 (1951): 9. This reading is accepted by such scholars as C. Kerényi, Dionysos, Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life (Princeton, 1976), 279 and Parisinou (n. 14), 165.

24. Parisinou (n. 14), 163 and 165.

25. Furley (n. 12), 92–4.

26. Schol. Ar. Ran. 479. This well-known passage has been more recently treated in length by N. Spineto, Dionysos a teatro (Rome, 2005), 148–53. However, the specific mention of the Lenaia contest proves that the ritual is not nocturnal.

27. R. Seaford, “Dionysos Destroyer of the Household,” in Masks of Dionysus, ed.T. H. Carpenter and C. A. Faraone (Ithaka, and London, 1993), 135, aptly comments: ‘Dionysus and Hera are of course natural enemies.’

28. Plut. Mor. fr. 157.2 (F.H. Sandbach, Plutarch’s Moralia XV. Fragments, Harvard 1969), apud Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelii 3, 1, 2: ‘…it is said that the priestesses of the two divinities at Athens do not speak to one another if they meet….’

29. See the penetrating comments of H. Jeanmaire, Dionysos. Histoire du culte de Bacchus (Paris, 1951), 198–216.

30. C. Picard, “La triade Zeus-Héra-Dionysos dans l’Orient hellénique d’après les nouveaux fragments d’Alcée,” BCH 70 (1946): 455–73; E. Will, “Autour des fragments d’Alcée récemment retrouvés: trois notes à propos d’un culte de Lesbos,” Revue Archéologique 39 (1952): 156–69. Note, however, that Dionysos is not Hera’s son in this context, since he is explicitly called the son of Thyone by Sappho (fr. 28, 9).

31. The analogous case of Herakles’ adoption by Hera, a myth prominent in Italy, but virtually absent in Greece, can be brought in support of such a suggestion: see recently T. Rasmussen, “Herakles’ Apotheosis in Etruria and Greece,” AK 48 (2005): 30–39.

32. Jahn (n. 18), lxi, n. 402; Becatti (n. 23), 9.

33. R. Benassai, “Sui dinoi bronzei capuani,” in Studi sulla Campania preromana (Roma, 1995), 175–76. See also L. Cerchiai, “Le tombe ‘a cubo’ di età tardoarcaica della Campania settentrionale,” in Il Mare, La Morte, L’Amore. Gli Etruschi, i Greci e l’immagine, ed. B. D’Agostino and L. Cerchiai, (Napoli, 1999), 163–70; Reusser (n. 18), 163–64, n° 30 and M. Martelli, “Arete ed eusebeia: le anfore attiche nelle necropoli del Etruria campana,” in Il greco, il barbaro e la ceramica attica. Immagi- nario del diverso, processi di scambio e autorappresentazione degli indigeni. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi 14–19 maggio 2001, Catania, Caltanisseta, Gela, Camarina, Vittoria, Siracusa, Vol. 3, ed. F. Giudice and R. Panvini, (Rome, 2006), 10 and 14.

34. London, The British Museum 560. On the lebes, see Benassai (n. 33) 161–62 and Cerchiai (n. 33), 166–68, pl. 90–91.

35. London, the British Museum 1920.6–13.1: ARV² 88.1, 1625; Add² 170; Cerchiai (n. 33), pl. 92–93.

36. Cerchiai (n. 33), passim.

37. N. Lubtchansky, Le cavalier tyrrhénien. Représentations équestres dans l’Italie archaïque, Bibliothèque des écoles françaises d’Athènes et de Rome 320 (Rome, 2005), 94–102.

38. Dion. Hal. Ant Rom. VII, 2.

39. The dionysiac connection is also stressed by Martelli (n. 33), 14.

40. R. Turcan, “Bacchoi ou Bacchants? De la dissidence des vivants à la segregation des morts,” in L’Association dionysiaque dans les Sociétés anciennes. Actes de la table ronde organise par l’École française de Rome, Rome 24–25 mai 1984 (Rome, 1986), 227–46, with earlier bibliography.

41. Collected and discussed by M. Rendelli, “Rituali e immagini: gli stamnoi attici di Capua,” Prospettiva 72 (1993): 2–16.

42. J. De La Genière, “Vases des Lénéennes?,” MEFRA 99 (1987): 43–61. 43. J. D. Beazley, “Prometheus Fire-Lighter,” AJA

43 (1939): 628–29.

44. Würzburg, Martin-von Wagner Museum H 4906, from Selinunt, once in the Giudice collection in Agrigento and then in the Jacob Hirsch collection in Zurich: Beazley (n. 43), 627, fig. 7; LIMC 3 (1986), pl. 312, Dionysos 149 (the vase is listed twice, [440, nos 149–150], once in its former and once in its present location).

45. R. Seaford, “Mystic Light in Aeschylus’ Bassarai,” CQ 55 (2005), 602–6. See also his paper in this volume.

46. Actually in a private collection in Switzerland: ARV² 1676.37; Add² 310; E. Simon, “Ein Anthesterien-Skyphos des Polygnotos,” in Ausgewählte Schriften. Band I, Griechische Kunst, ed. E. Simon (Mainz, 1998; originally published in AK 6 [1963]), 136–37, fig. 12.1–3; Kerényi (n. 23), fig. 97; E. Keuls, The Reign of the Phal- lus. Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens (New York, 1985), 374, fig. 315.

47. Simon (n. 46), 136–37. This identification has been largely adopted: see for instance Kerényi (n. 23), 313; Keuls (n. 46), 374; A. Avagianou, Sacred Marriage in the Rituals of Greek Religion (Bern, Berlin, New York, Paris, and Vienna, 1990), 185. On the ritual of the sacred marriage see especially W. Burkert, Homo Necans. The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London, 1983), 230–38; Avagianou, Sacred Marriage in the Rituals of Greek Religion, 177–97; S. Humphreys, The Strangeness of Gods. Historical Perspective on the Interpretation of Athenian Religion (Oxford, 2004), 252–53 and 270–71; R. Parker, Polytheism and Society at Athens (Oxford, 2005), 303–5 and Spineto (n. 26), 76–86.

48. On the various stages of initiation in imagery, see C. Bron, “Porteurs du thyrse ou bachants,” in Images et Société en Grèce ancienne. L’iconographie comme méthode d’analyse. Actes du Colloque international, Lausanne 8–11 février 1984, ed. C. Bérard, C. Bron and A. Pomari (Lausanne, 1987), 145–53.

49. T. H. Carpenter, Dionysian Imagery in Fifth Century Athens (Oxford, 1997), 33–34; Parisinou (n. 14), 118 and G. Fahlbusch, Die Frauen im Gefolge des Dionysos auf attischen Vasenbildern des 6. und 5. Jhs. V. Chr. Als Spiegel des weibichen Ideal- bildes (Oxford, 2004), 14.

50. Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum 14107 (once in the Scheurleer collection in the Hague): ABL 55; ABV 345; W. D. J. Van de Put, Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum The Netherlands, Fascicule 9, Amsterdam Fascicule 3, Allard Pierson Museum, Uni- versity of Amsterdam. Black-Figure, Pattern and Six-Technique Lekythoi (Amsterdam, 2006), 5–8, pl. 146–47.

51. The British Museum E 279. ARV² 226.1; Add² 199; J. D. Beazley, “The Master of the Eucharides-Stamnos in Copenhagen,” BSA 18 (1911–1912), pl. XI–XII; LIMC 3 (1986), pl. 535, Dionysos 478. Beazley called the woman Ariadne, because of her dignity.

52. Paris, Louvre G 202: ARV² 226.4; Beazley (n. 51), 222, fig. 4.

53. Malibu, The J.P. Getty Museum 84.AE.770: D.C. Kurtz, “Two Athenian White-ground Lekythoi,” in Greek Vases in the Getty Museum, 4, Occasional Papers on Antiquities, 5 (Malibu, 1989), 114–18, fig. 1a–e.

54. Paris, Louvre G 135: ARV² 355.45. On the notion of the dionysiac thiasos as a New Age ‘hippy convoy,’ see J. Gould, “Dionysus and the Hippy Convoy: Ritual, Myth, and Metaphor in the Cult of Dionysus,” in Myth, Ritual, memory and Ex- change. Essays in Greek Literature and Culture, ed. J. Gould (Oxford, 2001), 269–82.

55. G. M. Hedreen, “The Return of Hephaistos, Dionysiac Processional Ritual and the Creation of a Visual Narrative,” JHS 124 (2004): 42 (who adds further: ‘I envision Athenian vase-painters constructing visual representations of the Return of Hephaistos by extracting elements of spectacle from Athenian religious life and employing them in the vase-paintings in order to give recognizable form to the principal themes of the myth’).

56. M. Halm-Tisserant, “La représentation du retour d’Héphaïstos dans l’Olympe,” AK 29 (1986): 13.

57. The motif appears often in the repertoire of the Christie Painter: ARV² 1047.10–6.

58. See for example ARV² 484.11, 487.62, 495.4, 511.5, 512.8; 518.13, 525.41, 668.24, 953.46, 992.74, 1048.41, 1151.1, 1188.3.

59. Ferrara, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 45698, calyx-krater from Spina, tomb 112 D of the Valle Pega necropolis, by the Mykonos Painter: ARV² 515.9bis; Diony- sos. Mito e Mistero, ed. F. Berti, & C. Gasparri (Bologna, 1989), 27–28, n° 1 (450 BCE). See also a column krater by the Orchard Painter at Gela, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 40384 (450 BCE): ARV² 525.32; R. Panvini, Ceramiche attiche figurate del Museo Archeologico di Gela: Selectio Vasorum (Venice, 2003), 93, n° 11.26.

60. Eur. Trojan Women 348–9. See Seaford (n. 27), 128. Torches are held upright by a male dancer on a red-figured salt-cellar in Bonn University, inv. 994: J. H. Oakley and R. H. Sinos, The Wedding in Ancient Athens (Madison, 1992), 94, fig. 79.

61. Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 3950 and Greifswald 340: ARV² 914.142; J. Neils, “Looking for the Images: Representations of Girls’ Rituals on Ancient Athens,” in Finding Persephone. Women’s Rituals in the Ancient Mediterranean, ed. M. Parca and A. Tzanetou (Bloomington & Indianapolis, 2007), 67–69, fig. 3.6a–c.

62. On the Gerarai, see Burkert (n. 47), 232, n. 8, Humphreys (n. 47), 233–6, Parker (n. 47), 304–6 and Spineto (n. 26), 77–79. Neils (n. 61), 67–69, thinks that the seated male figure on the tondo might be the Archon Basileus at the Anthesteria. However, she does not connect the scene on the exterior with the Anthesteria, since she makes the questionable assumption that the girl on the left side of the vase is a dwarf and that the torches held by the woman to the right are sticks. Consequently, she connects the scene to the cult of Demeter, where ritual whipping is attested in ancient sources. Of course, there can be no doubt that the woman is holding a pair of short torches and not sticks; compare with the torches illustrated on London, British Museum E 279 [Figure 17.3] and Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum, inv. 14107 [Figure 17.4] . As for the dwarfishness of the girl to the left, it might be simply an indication of its small age, since, according to Aristotle (Parts of Animals 4, 10, 686b 6–9, 11), “all children are dwarfs.” On this aspect of child imagery, see V. Dasen, “‘All Children are Dwarfs.’ Medical Discourse and Iconography of Children’s Bodies,” OJA 27 (2008): 49–62.

63. Allard Pierson Museum 8921: Sotheby’s 3.12.1973, n° 154.

64. B. Bravo, Pannychis e simposio. Feste private notturne di donne e uomini nei testi letterari e nel culto (Pisa-Rome, 1997).

65. For a full recent treatment, see R: Hamilton, “Lenaia Vases in Context,” in Poetry, Theory, Praxis. The Social Life of Myth, Word and Image in Ancient Greece. Essays in Honor of William J. Slater, ed. E. Csapo, E. and M. C. Miller (Oxford, 2003), 48–68. Note also the cautious analysis in Parker (n. 47), 306–12.

66. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 2419: ARV² 1151.2; Add² 336; Kerényi (n. 23), fig. 85; LIMC 3 (1986), pl. 298, Dionysos 33; Carpenter (n. 49), pl. 25B.

67. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 90.155: ARV² 621.34; Add² 270; Parker (n. 47), 310–11, fig. 21a–b.

68. M. Dillon, Girls and Women in Greek Religion (London & New York, 2001), 148.

69. See Humphreys (n. 47), 223–75, for an analysis of the Anthesteria along similar lines.

70. The painter Epiktetos was the first who showed thyrsi on his vases; see for example the cup in Paris, Louvre G6: ARV² 72.21; D. Paleothodoros, Épictétos (Leuven, Namur, Boston, and Duddley, 2004), 154, n° 50, pl. XVII.1–3.

71. M. Edwards, “Representations of Maenads on Archaic Red-Figure Vases,” JHS 80 (1960): 80; A. Henrichs, “Myth Visualized, Dionysos and his Circle in SixthCentury Attic Vase-Painting,” in Papers on the Amasis Painter and his World, ed. M. True (Malibu, 1987), 100–103.

72. The quotation is from Rohde (n. 11) 256. Thysthla: Homer, Il. 6, 133–35. For the meaning ‘thyrsus,’ see a third century satyr drama published by D. F. Sutton, Papyrological Studies in Dionysiac Literature (Illinois, 1987), 65 and 75. In general, Paleothodoros (n. 70), 81–82.

73. R. Osborne, “The Ecstasy and the Tragedy: Varieties of Religious Experience in Art, Drama, and Society,” in Tragedy and the Historian, ed. C. Pelling (Oxford, 1997), 198.

74. This has been perceived intuitively by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema who painted the Dedication to Dionysus (Hamburg Kunsthalle) in 1889: Bacchants are shown holding blazing torches, while the blue color of the sky shows that the ritual takes place during daytime.

75. This fact is best shown on a splendid giant Apulian skyphos in the Gnathia (Bonn 1201): a huge vine branch frames a three-legged table with two kantharoi and an egg to either side of a torch: J. R. Green, Gnathia Pottery in the Akademische Kunstmuseum, Bonn (Mainz, 1976), 17–18, pl. 1–2. This vase has been used as an ash-container in a grave of the mid-4th century excavated at Bacoli near Naples in 1852.

ABL. Haspels, E. C. H. Attic Black-Figure Lekythoi. Paris, 1936.

ABV. Beazley, J. D. Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1956.

Add². Carpenter, T. H. (ed.), Beazley Addenda², Oxford, 1989.

ARV². Beazley, J. D. Attic Red-Figured Vase-Painters². Oxford, 1963.

Avagianou, A. Sacred Marriage in the Rituals of Greek Religion. Bern-Berlin-New York-Paris-Vienna, 1990.

Beazley, J. D. “The Master of the Eucharides-Stamnos in Copenhagen.” Annual of the British School of Athens 18 (1911–1912): 217–233, pl. X–XV.

———. “Prometheus Fire-Lighter.” American Journal of Archaeology 43 (1939): 618–39.

Becatti, G. “Rilievo con la nascita di Dionysos e aspetti mistici di Ostia pagana.” Bol- lettino d’Arte 36 (1951): 1–16.

Benassai, R. “Sui dinoi bronzei capuani.” Pp. 157–205 in Studi sulla Campania preromana. Roma, 1996.

Berti, F. and Gasparri, C. eds. Dionysos. Mito e Mistero. Bologna, 1989.

Braund, D. “Palace and polis: Dionysus, Scythia and Plutarch’s Alexander.” Pp. 15–31 in The Royal Palace Institution in the First Millenium B.C. Regional Develop- ment and Cultural Interchange between East and West, vol. IV, edited by I. Nielsen, Athens, 2001.

Bravo, B. Pannychis e simposio. Feste private notturne di donne e uomini nei testi letterari e nel culto. Pisa-Roma, 1997.

Bremmer, J. “Greek Maenadism Reconsidered.” Zeitschrift fürPapyrologie und Epi- grafik 55 (1984): 267–86.

Bron, C. “Porteurs du thyrse ou bachants.” Pp. 145–53 in Images et Société en Grèce ancienne. L’iconographie comme méthode d’analyse. Actes du Colloque interna- tional, Lausanne 8–11 février 1984. edited by C. Bérard, C. Bron, and A. Pomari. Lausanne: Cahiers d’Archéologie Romande, n° 36, Institut d’Archéologie et d’Histoire Ancienne: Université de Lausanne, 1987.

Bruchman, C. F. H. Epitheta Deorum quae apud poetas graecos leguntur. Leipzig, 1893.

Burkert, W. Homo Necans. The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth, Berkeley—Los Angeles—London, 1983.

———. Ancient Greek Religion, Archaic and Classical, translated by J. Raffan, Oxford, 1985.

Carpenter, T. H. Dionysian Imagery in Fifth Century Athens, Oxford, 1996.

Cerchiai, L. “Le tombe ‘a cubo’ di età tardoarcaica della Campania settentrionale.” Pp. 163–70 in Il Mare, La Morte, L’Amore. Gli Etruschi, i Greci e l’immagine, edited by B. d’Agostino and L. Cerchiai, Napoli, 1999.

Cook, A. B. Zeus. A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. 2. Cambridge, 1923.

Dasen, V. “All Children are Dwarfs.” Medical Discourse and Iconography of Children’s Bodies. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 27 (2008): 49–62.

De La Genière, J. “Vases des Lénéennes?” Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome. Antiquité 99 (1987): 43–61.

De Ridder, A. Catalogue des vases peints de la Bibliothèque National. Paris, 1904.

Dillon, M. Girls and Women in Greek Religion, London, and New York, 2001.

Edwards, M. “Representations of Maenads on Archaic Red-Figure Vases.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 80 (1960): 78–87.

Fahlbusch, G. Die Frauen im Gefolge des Dionysos auf attischen Vasenbildern des 6. und 5. Jhs. V. Chr. Als Spiegel des weibichen Idealbildes. Oxford, 2004.

Furley, W. D. Studies in the Use of Fire in Ancient Greek Religion, Salem (New Hampshire), 1981.

Gasparri, C. and A. Veneri. “Dionysos.” Pp. 414–514 in LIMC 3, 1986.

Goff, B. Citizen Bacchae. Women’s Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece, Berkeley—Los Angeles—London, 2004.

Gould, J. “Dionysus and the Hippy Convoy: Ritual, Myth, and Metaphor in the Cult of Dionysus.” Pp. 269–82 in Myth, Ritual, Memory and Exchange. Essays in Greek Literature and Culture, edited by J. Gould, Oxford, 2001.

Green, J. R. Gnathia Pottery in the Akademische Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Mainz, 1976.

Halm-Tisserant, M. “La représentation du retour d’Héphaïstos dans l’Olympe,” An- tike Kunst 29 (1986): 8–22.

Hamilton, R. “Lenaia Vases in Context.” Pp. 48–68 in Poetry, Theory, Praxis. The Social Life of Myth, Word and Image in Ancient Greece. Essays in Honor of Wil- liam J. Slater, edited by E. Csapo, E. and M. C. Miller, Oxford, 2003.

Hedreen, M. G. “Silens, Nymphs, and Maenads.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 114 (1994): 47–69.

———. “The Return of Hephaistos, Dionysiac Processional Ritual and the Creation of a Visual Narrative.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 124 (2004): 38–64.

Henrichs, A. “Myth Visualized, Dionysos and his Circle in Sixth-Century Attic VasePainting.” Pp. 92–124 in Papers on the Amasis Painter and his World, edited by M. True, Los Angeles, 1987.

Humphreys, S. The Strangeness of Gods. Historical Perspective on the Interpretation of Athenian Religion. Oxford, 2004.

Isler-Kerényi, Cornélia. Dionysos nella Grecia arcaica. Il contributo delle immagini, Pisa, and Roma, 2001.

Jahn, O. Beschreibung des Vasensammlung König Ludwigs in der Pinakothek zu München, München, 1854.

Jeanmaire, H. Dionysos. Histoire du culte de Bacchus, Paris, 1951.

Kerényi, C. Dionysos. Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, translated by R. Mannheim. Bollingen Series LXV 2, New Jersey, 1976.

Kern, O. “Dionysos,” columns col. 1010–1046 in Paulys Real-Encyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswisseschaft, edited by P. Wissowa, Vol. 5, Stuttgart, 1903.

Keuls, E. The Reign of the Phallus. Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens, Berkeley-Los Angeles-London, 1985.

Kretchmer, P. “Dionysos und Semele,” Pp. 17–29 in Aus der Anomia, Archäologische Beiträge Carl Robert dargebracht, Berlin, 1890.

Kurtz, Donna C. “Two Athenian White-ground Lekythoi,” Pp. 113–30 in Greek Vases in the Getty Museum, 4, Occasional Papers on Antiquities, 5, Los Angeles, 1989.

LIMC: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, volumes 1–8, Zurich, 1981–1997.

Lubtchansky, N. Le cavalier tyrrhénien. Représentations équestres dans l’Italie ar- chaïque (Bibliothèque des écoles françaises d’Athènes et de Rome 320), Rome, 2005.

Martelli, M. “Arete ed eusebeia: le anfore attiche nelle necropoli del Etruria campana,” Pp. 7–37, pl. I–IV in Il greco, il barbaro e la ceramica attica. Immaginario del diverso, processi di scambio e autorappresentazione degli indigeni. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi 14–19 maggio 2001, Catania, Caltanisseta, Gela, Camarina, Vittoria, Siracusa, 3. Roma, 2006.

Minervini, G. Monumenti antichi inediti posseduti da Raffaele Barone. Napoli, 1850.

Moraw, S. Die Mänade in der attischen Vasenmalerei des 6. und. 5. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Mainz, 1997.

Neils, J. “Looking for the Images: Representations of Girls’ Rituals on Ancient Athens.” Pp. 55–78 in Finding Persephone. Women’s Rituals in the Ancient Mediter- ranean. edited by M. Parca and A. Tzanetou. Bloomington, and Indianapolis, 2007.

Oakley, J. H. and R. H. Sinos. The Wedding in Ancient Athens. Madison, 1993.

Osborne, R. “The Ecstasy and the Tragedy: Varieties of Religious Experience in Art, Drama, and Society.” Pp. 187–211 in Tragedy and the Historian. edited by C. Pelling. Oxford, 1997.

Paleothodoros, D. Épictétos. Leuven-Namur-Boston-Duddley, 2004.

Panvini, R. Ceramiche attiche figurate del Museo Archeologico di Gela: Selectio Vasorum. Venezia, 2003.

Parisinou, E. The Light of the Gods. The Role of Light in Archaic and Classical Greek Cult. London, 2003.

Parker, R. Polytheism and Society at Athens, Oxford, 2005.

Picard, C. “La triade Zeus-Héra-Dionysos dans l’Orient hellénique d’après les nouveaux fragments d’Alcée,” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 70 (1946): 455–73.

Rasmussen, T. “Herakles’ Apotheosis in Etruria and Greece,” Antike Kunst 48 (2005): 30–39.

Rendelli, M. “Rituali e immagini: gli stamnoi attici di Capua.” Prospettiva 72 (1993): 2–16.

Reusser, C. Vasen für Etrurien. Verbreitung und Funktionen Attischer Keramik im Etrurien des 6. und 5K Jahrhunderts vor Christus, Zürich, 2002.

Rohde, E. Psyche. The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality among the Ancient Greeks, trans. W. B. Hills, London, and New York, 1925 (Reprinted 1987).

Schöne, A. Der Thiasos. Eine Ikonographische Untersuchung über das Gefolge des Dionysos in der attischen Vasenmalerei des 6. und 5. Jhs. V. Chr. , Göteborg, 1987.

Seaford, R. “Dionysos Destroyer of the Household,” Pp. 115–146 in T Masks of Dionysus, edited by H. Carpenter and C. A. Faraone. Ithaka, and London, 1993.

———. “Mystic Light in Aeschylus’ Bassarai. ” Classical Quarterly 55 (2005): 602–606.

Simon, E. “Ein Anthesterien-Skyphos des Polygnotos.” Pp. 135–160 in Simon, E., Ausgewählte Schriften. Band I, Griechische Kunst, Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1998 (originally published in Antike KunstK 6 [1963]: 6–22). Spineto, Natale. Dionysos a teatro. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2005.

Sutton, Diana F. Papyrological Studies in Dionysiac Literature, Illinois: BolchazyCadrucci Publishers, 1987.

Turcan, Robert. “Bacchoi oi Bacchants ? De la dissidence des vivants à la ségrégation des morts.” Pp. 227–46 in l’Association dionysiaque dans les Sociétés anciennes. Actes de la table ronde organise par l’École française de Rome, Rome 24–25 mai 1984, Rome: École Française de Rome, 1986.

Van de Put, Winfred D.J. Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum The Netherlands, Fascicule 9, Amsterdam Fascicule 3, Allard Pierson Museum, University of Amsterdam. Black- Figure, Pattern and Six-Technique Lekythoi. Amsterdam : Allard Pierson Series, 2006.

Will, Éduard. “Autour des fragments d’Alcée récemment retrouvés: trois notes à propos d’un culte de Lesbos.” Revue Archéologique 39 (1952): 156–169.