Traditional Criticisms of Romanticism: Narcissus at the Pool and the Platonic-Romantic Dream of Arcadia

Romanticism is often criticized for resulting in an attitude that is too sentimental, too self-absorbed and even narcissistic, and too unconcerned with politics—or if it is political, then in an entirely bad or evil way. It is said to lead to authoritarianism and totalitarianism, especially Nazism. I articulate some of these criticisms by reviewing Babbitt’s Rousseau and Romanticism (1919), in which he criticizes Rousseau, Wordsworth, and other romantics. I also briefly discuss Berlin’s and Popper’s assessment of romanticism, which enables us to further explore the supposedly antagonistic relation between romanticism and liberalism—a relation that will turn out to be much less straightforward than usually assumed by romanticism’s critics.

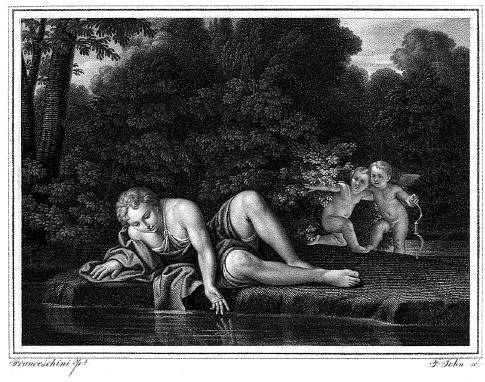

Figure 6.1 Friedrich John, Franceschini, Marco Antonio: Narcissus, 1830 (copperplate). Salzburg: Universitätsbibliothek Salzburg, Graphiksammlung, G 822 II.

Narcissus’s Reverie: Babbitt’s Criticism of Rousseau

In 1919 Irving Babbitt, an American professor of French literature at Harvard University and literary critic, objected to what he took to be Rousseau’s romanticism. What did Babbitt mean by “romanticism”? He defines the romantic as the “wonderful”: “A thing is romantic when it is strange, unexpected, intense, superlative, extreme, unique, etc.” (4) It can also mean “wild, unusual, adventurous” (7). He contrasts Rousseau’s romanticism with Voltaire’s classicism. Genius is not about imitation, Rousseau thought, but about the “refusal to imitate” (34). Romanticism emphasizes feeling and the breaking down of barriers, and seeks the extreme. Romantics do not “shrink at the wildest excess of emotional unrestraint” (97). They cherish illusion for its own sake (260). They are lovers of delirium: in contrast to “genuine religion“ (182), which seeks the infinite of religion and conversion (252), tormented by the demon in their heart (252), they pursue “delirium, vertigo and intoxication for their own sake” (180) in their “cult of intoxication” (183) and suffer from restlessness (252) as they experience infinite nostalgia (251). They value spontaneity and childhood. They desire a utopian dream land, which they place in ancient Greece or (later) in the Middle Ages. They prefer the simple and primitive life, and follow the voice of nature rather than being “perverted by society” (131). Rousseau went into the wilderness “to affirm his freedom from conventional restraint and at the same time to practice the new art of revery” (277). He wished to “fall into an inarticulate ecstasy before the wonders of nature” (285), seeking an “ecstatic” animality (286). For Babbitt, this is all temperamental and a desire for “unreality” (110). Instead of analysis or reality, romanticism wants “illusion” (185). The imagination is used to escape to dreamland, where there is neither inner nor outer control. Ethically speaking, it is “glorification of instinct” (147) rather than “inner” check, which is according to the ancient Hindu divine (148). It is irrationality and madness, and in the case of Rousseau even psychosis: “He abandoned his five children one after the other, but had we are told an unspeakable affection for his dog” (143). But what was Babbitt’s own view?

According to Babbitt, Rousseau was too sentimental. Although he valued art and imagination, Babbitt thought that what humanism really needs is discipline. He argued against the aim to gain emotional unity through intoxication (184). Rather than wasting ourselves, Babbitt argues, we should exercise “sober discrimination” (184). Instead of primitivism, we need civilization. His humanist ethics is one of restraint. Although life is but a dream (Babbitt quotes Shakespeare’s famous lines here), “it is a dream that needs to be managed with the utmost discretion” (xiv). Note, however, that Babbitt also rejected positivism, Cartesian mechanism, and utilitarian and scientific naturalism, which he regarded as another naturalist excess. His book on Rousseau is directed against “emotional naturalism” (x). Against the “oneness” of naturalism and against Rousseau’s belief in natural goodness, Babbitt relies on Aristotelian dualism: we have two selves, a “natural” and a “human” one, and we should “not let impulse and desire run wild” (16). We have to follow the latter: our “ethical self” (49). For Babbitt, imagination plays an important role in life, but he argued against the Romantic imagination, which he says “has claimed for itself a monopoly of imagination” (18). He prefers “the ethical imagination,” which follows the law of heaven. Platonically, Babbitt thinks that human law is only a shadow of this (48). We have to use our imagination in order to “imitate rightly” (69). The classical imagination is not free “to wander wild in some empire of chimeras” but “is at work in the service of reality” (102). The romantics, by contrast, long “to escape from the oppression of the actual into some land of heart’s desire.” Babbitt rejects such “dangerous prevalence of daydreaming” and the “vagabondage” of Rousseau’s wanderings (72). While a longing for Arcadia is ineradicable (73), he warns that one should not blur the boundaries between “statues” and “living men” or between fact and fiction; this could lead to madness (73). Against eighteenth-century rationalism, romantics want unity, but, he asks, “What is the value of unity without reality?” (185).

Babbitt also rejected not so much modern individualism but romantic individualism, which he claims does not recognize a measure outside itself: “His own private and personal self is to be measure of all things and this measure itself, he adds, is constantly changing” (xii). Against the romantic concept of genius and its focus on uniqueness, Babbitt defends the “Greek” idea that the genius perceives the universal, with the aid of the imagination—a “strict discipline of the imagination to a purpose” rather than a free imagination (41–42). Rousseau contrasts nature with convention, and if we have chosen convention, this is a kind of Fall:

In permitting his expansive impulses to be disciplined by either humanism or religion man has fallen away from nature much as in the old theology he has fallen away from God, and the famous “return to nature” means in practice the emancipation of the ordinary or temperamental self that had been thus artificially controlled. (Babbitt 1919, 45–46)

Instead of imitation, the romantic genius wants to attain self-expression. We should not lock ourselves up in “a set of formulae”; we are unique (46). Romantics such as Rousseau were “quite overcome” by their “own uniqueness and wonderfulness” (50). They feel amazed at themselves. Instead of establishing “orderly sequences and relationships and so work out a kingdom of ends,” the “Rousseauist” (Babbitt’s term) embraces wonder and “the creative impulse of genius as it gushes up spontaneously from the depths of the unconscious” (51). Ignorance and innocence are praised; rationality is sacrificed. The aim is to sink back to the “state of childlike wonder” (51) since it is thought that “what comes to the child spontaneously is superior to the deliberate moral effort of the mature man” (52). Instead of the Rousseauist, who “specializes in his own sensations” (58), Babbitt argues for ethics, a dualist one that draws us out of our “ordinary self” and toward an “ethical center.” According to him “genuine religion must always have in some form the sense of a deep inner cleft between man’s ordinary self and the divine” (115). The romantic, by contrast, rejects this ethical center as artificial (53) and strives for oneness. Genius is “hindered rather than helped by culture” (65). The romantic wants to shock the philistine by means of the “violence of eccentricity” (64). But, Babbitt argues, this is also lazy: it is easy to be a Rousseauist following your temperament, whereas to become an ethical person requires more work (65). If you want to become a genius, you have to “bestir yourself”; genius is not “a temperamental overflow” (66). Referring to the Confessions, he accuses Rousseau of lacking humility and rejects his focus on the “ordinary” self (127–128). The (true, classical) humanist wants to improve the self, wants to become more virtuous rather than following natural passions. “Even” the Buddhists, misused by romanticists such as Arthur Schopenhauer, offered “a psychology of desires” (149) aimed at “inhibition or inner check upon expansive desire”—in other words, an ethics of control (150). We have to overcome our inner laziness; we are not naturally good as Rousseau thought. The latter is, according to Babbitt, “an encouragement to evade moral responsibility” (155). We must remain fighters in the “civil war in the cave” (187) and reject the lazy peace of following our passions.

Romanticism, Babbitt suggests, boils down to egoism: romantics are “men who have repudiated outer control without acquiring self-control” (192). It gives us the moral psychology of the restless “half-educated man … who has acquired a degree of critical self-consciousness sufficient to detach him from the standards of his time and place, but not sufficient to acquire new standards that come with a more thorough cultivation” (194). Romantics want to have it all (peace and brotherhood) without paying the price (restraint). Like Nietzsche’s superman, the romantics want “infinitude” and resist proportionateness. But the latter, Babbitt holds, is an important virtue. Instead of wanting infinity, we should adjust ourselves to “the truth of the human law” (195). We need ethos, not pathos (201); we need to take distance from convention but by means of the Socratic ethical self, not our “unique and private self” (245). We have to learn to say “no” rather than “yes.”

Babbitt also rejects political romanticism. This means for him rejecting the following: a society without traditional inhibitions (193), the aspiration of plebian people to be taken seriously rather than being mocked in comedy, the fascination with “every form of insurgency” such as the heroic insurgencies of Prometheus and Satan (139), the “fraternal spirit” (140) instead of self-control and other personal virtues, and the “new morality” according to which employers should pay a working girl more in order to avoid her taking up prostitution and the related “tendency to make of society the universal scapegoat.” Babbitt justifies the latter by saying that we should “find mechanical or emotional equivalents for self-control” (156). Rather than changing society, then, Babbitt’s classical humanist ethics and political conservatism asks of “man” and “the working girl” to restrain themselves. We have to make ourselves (163); we cannot blame outer, natural forces. By embracing natural passions and forces, romanticism instead discredits “moral effort on the part of the individual” (163). Romanticism, he suggests in a fully sexist mode, should be left to women, who “are more temperamental than men” (158) and to men like Rousseau who shares “this feminine fineness of temperament” and whose “mingling of sense and spirit” is “also a feminine rather than a masculine trait” (158).

Thus, Babbitt’s political view turns out to be in line with traditional and conservative Western thinking about ethics and about men and women. If women are like the moon and men like the sun (159), then Romanticism is “bathed in moonshine” (159)—in other words, Babbitt sees it as too feminine. Elsewhere he also speaks of nature as our “mysterious mother”: for Babbitt, women are (potential) prostitutes, workers, or mysterious divine beings. He prefers a classical male-centered ethics, an ethics that aims at what we may call “making men,” rather than women or—worse—hybrids. A man knows how to control himself and tries to achieve clarity by means of analysis. Romantics, Babbitt argues, prefer darkness and the twilight. These “twilight men” admire in women “her unconsciousness and freedom from analysis” (159). (Yet in another place he rejects the supposedly “medieval” view that “woman is … depressed below the human level as the favorite instrument of the devil in man’s temptation … or else exalted above this level as the mother of God” [221].)

Babbitt presents a very one-sided reading of Rousseau and, for instance, completely fails to see Rousseau’s Stoicism. The book is also rather unfair as an assessment of Romantic thinking as a whole, which, as we have seen, is much richer than a simple appeal to sentiment or a celebration of primitivism. For instance, many romantics thought about how to change society and improve the lives of others. They have been daydreaming, for sure, but frequently their dream concerned revolutionizing the world—transforming society and culture rather than only themselves. Furthermore, although they were often inspired by more archaic cultures and societies such as those found in ancient Greece, many of them, including Rousseau, did not preach an actual return to those societies, let alone to so-called primitive societies. Instead, many were interested in reimagining modern society: reenchanting it, making it more whole, rendering it less “artificial.” Moreover, they highlighted sentiment and pointed to the limitations of rational thinking, especially what would later be called instrumental rationality, but most romantics did not reject reason or rationality as such. It seems that they rather criticized the unbalance between the sentiment and rationality that they found in the Enlightenment. Finally, Babbitt’s political conservatism is disappointing, if not shocking, and his remarks about women are unacceptable in the eyes of a contemporary reader, if not already in this own time. His conservatism could be criticized on the basis of Enlightenment thinking. And the romantics were not always as conservative and sexist as Babbitt. For example, in William Morris, we find a slightly more ambiguous view, including what is perhaps a mixture of traditional and more progressive beliefs about women and about relationships. In his utopia, there is still a traditional division of labor: women are respected as child bearers and work mainly in the household. But Morris also argues against oppression of women by men and at least leaves room for women to do other things as well. Thus, when it comes to gender, Babbitt’s humanism may actually be more conservative than the views of some of the romantics he criticizes. Furthermore, in contrast to Babbitt, romantics were also influenced by Enlightenment ideas. And finally, Babbitt’s humanism seems to be nostalgic about a constructed ancient Greek past when men “knew how to control themselves.” This could also be seen as a form of romanticism.

However, there is also some truth in Babbitt’s descriptions of romantic thinking and practice. For instance, he is right when he says that Rousseau sets up a new dualism between artificial society and nature (130). Incidentally, perhaps he is also right that we are living in a world where dogs (“here,” our pets) are often better treated than other people (people who are “elsewhere,” out of view). This may indeed have to do with romanticization. And his remark that most romantics “showed themselves very imitative even in their attempts at uniqueness” (61) still holds in our time: we all want to be unique romantic individuals, but in practice, this often leads to imitation rather than true uniqueness (whatever that may mean). In many ways, in spite of our search for romantic uniqueness and perhaps partly because of our romanticism, we are still living in a society that is similar to the mass society and the consumerist society criticized by twentieth-century thinkers. Our romantic selves have fallen prey to advertisement, marketing, manipulation, commodification, and data milking. We do what “they” do—to use a term from Heidegger. This is very ironic, although irony was and, is of course, also romantic.

It is also true that there is a gap between our romantic attitude toward nature and actual practice, another problem Babbitt correctly identifies. In spite of our romantic reverence of natural beauty, we have done very little to preserve it. Babbitt writes about the nineteenth century: “No age ever grew so ecstatic over natural beauty as the nineteenth century, at the same time no age ever did so much to deface nature. No age ever so exalted the country over the town, and no age ever witnessed such a crowding into urban centers” (301). The same could be said about the past century. Furthermore, Babbitt blames this on “the Rousseauist” who is “simply communing with his own mood” (302). I think he is right to question self-absorption and contemplation, at least if this means the individual becomes more distant from the natural environment and no longer refers to anything or anyone outside herself. I have also criticized this kind of romanticism elsewhere when I argued against a romantic environmental ethics (Coeckelbergh 2015a). The myth of Narcissus can do some work here. And indeed Babbitt compares the Rousseauist to Narcissus, who only sees his own image in the pool. We are lost in melancholy and self-pity. If this is romanticism, then for sure it is highly problematic and we better make sure our new romantic technologies do not lead to a kind of cyber-romanticism understood as cybernarcissism. We do not want to become cyber-Narcissus—if only because that would mean that we die: only in death do we become totally related only to ourselves, that is, we become totally unrelated. (However, this assumes that such a death is possible; in the next section, I return to this issue.)

Furthermore, Babbitt (1919) criticizes not only “the Rousseauist” who escapes in reverie but also the Baconian scientist. He warns against all lusts, including the lust of knowledge: a Baconian humanity “is only an intellectual abstraction just as the humanity of the Rousseauist is only an emotional dream” (344). Babbitt sees that scientific and rationalistic humanitarianism are “subject to similar disillusions” (344). He also warns of “the most dangerous of all the sham religions1 of the modern age—the religion of country, the frenzied nationalism that is now threatening to make an end of civilization itself” (345). When there is a “union of material efficiency and ethical unrestraint” (346), we get imperialism and war. Babbitt suggests that Rousseau’s romanticism made possible German nationalism. Instead of following the humanistic Goethe (362), most people were induced by emotional romanticism.

This link to nationalist politics remains a problem for romanticism and raises the question: What should the relation be between emotions and politics? Does a rejection of political romanticism mean that emotions should play no role in politics? Would that be possible at all? And might there be good elements in political romanticism that should be saved, or does it necessarily lead to totalitarianism and tyranny? Is utopia always and necessarily bad? Is the analytical intellect better equipped to avoid these extremes, or can it also corrupt society—for instance, by means of lethal technologies or utilitarian politics? And what is the relation between romantic political utopianism and contemporary technology? Babbitt did not ask these questions but was certainly aware of the danger of “Baconian” projects. As an antidote, he defended the virtue of humility, which he calls “the supreme virtue of the humanist” (380). He says about science that it needs to know its proper place. In line with his ethics, he writes that the most important thing is self-mastery, not mastery over nature:

The discipline that helps a man to self-mastery is found to have a more important bearing on his happiness than the discipline that helps him to a mastery of physical nature. If scientific discipline is not supplemented by a truly humanistic or religious discipline the result is unethical science, and unethical science is perhaps the worst monster that has yet been turned loose on the race. (Babbitt 1919, 383)

Thus, for Babbitt, science and technology need to be kept within ethical limits by the virtue of self-mastery and self-discipline. However, I doubt if only scientific mastery is the problem, whereas self-mastery is not: perhaps both forms of mastery are problematic. Is discipline necessarily good? Do we have to choose between self-control or total lack of control? Is “control” the most important dimension for ethics? How much mastery and control is good for us? These questions strike at the heart of Babbitt’s humanism, which, like Romanticism, lives in that tension and that continuum. Can we leave it? Can we get beyond the control discussion? I say more about this in my final chapter. In any case, it is clear that Babbitt’s antiromanticism does not entail an uncritical support for science and technology.

Babbitt also has a point when he says that “genuine savages are … the most conventional and imitative of beings” (110). This is an incorrect presentation of Rousseau’s view, who was thinking of the simple life of the farmer rather than the “savage,” and who criticized a particular kind of conventionalist society rather than sociality as such. It is also misguided to think that some peoples are or were more conventional than others. And of course the uncritical term of the term savages in this text is annoying to contemporary critical readers. But Babbitt is right if he means that there is no original state of nature. Humans have always followed conventions and have always imitated others. We have always been social beings. We might be able to escape from the convention of our own society, but as Babbitt rightly remarks, the people we meet in foreign countries “have not escaped from their convention” (111). They also live in a society with its own “discipline” (11). Insofar as romanticism suggests otherwise, it is indeed mistaken.

Finally, insofar as romanticization and reenchantment take on an escapist, reverie type of form, they may indeed lead to disappointment and bitterness when they clash with the real: “The Rousseauist begins by walking through the world as though it were an enchanted garden, and then with the inevitable clash between his ideal and the real he becomes morose and embittered” (105). Using Jean Paul’s words, he writes that after the hot baths of sentiment, we get a cold douche of irony (264)—the irony of “emotional disillusion” (266).

However, both the romanticism criticized here and Babbitt’s objections to it presuppose a dream/real or virtual/real duality. In contrast to contemporary posthumanism, Babbitt’s humanism does not cross barriers.

Babbitt’s criticism of Rousseau and romanticism brings out what is at stake in the discussion about romanticism: it concerns human beings and ethics and, ultimately, the nature of reality. For instance, in light of our previous discussion about boundaries, it is interesting that Babbitt, referring to Goethe, wants to reinforce the boundary between dead “statues” and “living men” (73). Indeed, Goethe (1870) wrote, “As in Rome there is, apart from the Romans, a population of statues, so apart from this real world there is a world of illusion, almost more potent, in which most men live” (54). Babbitt reinforces this Platonic distinction between the real and illusion. He claims that we should discriminate between both worlds. Moreover, as an anti-Romantic, he clearly favors one side of the distinction: reality. He rejects Rousseau’s “pastoral dream” and his “primitivism” (Babbitt 1919, 76). He does not have a problem with longing for a golden age if this remains a kind of hobby, something for one’s leisure time, for women, or for art. But, he argues, we should not confuse such a fantasy world with a state of nature, and we should not reject civilized life in favor of “something that never existed” (79). In other words, he thinks that Rousseau’s Arcadia and Schiller’s Elysium are beautiful but should remain poetry, to be enjoyed in one’s free time. Rousseau’s state of nature belongs to “dreamland,” as does the romantic conception of a pure Greece presented by Schiller, Shelley, and Hölderlin: “a wonderland of unalloyed beauty” that is also “Arcadian sentimentalizing” (81). Novalis’s Middle Ages “never had any equivalent in reality” (110). The romantics want utopia; Babbitt choses the real. Against the “hypochondriac misery” (85) of Rousseau and his focus on feeling (87), which leads him to a reverie that naturalizes “man”—he says of Rousseau that he wanted to “become an oak tree and so enjoy its unconscious and vegetative felicity” (269)—Babbitt argues that reverie “should be allowed at most as an occasional solace from the serious business of living”; it should not be its substitute (90). He calls romantic philosophy “at best only a holiday or week-end view of existence” (289).

The romantic has nostalgia for the unknown, indeed for escaping home rather than homesickness (92–93). But such an epistemological project to explore the unknown and escape home leads to something Babbitt rejects: going “across all frontiers, not merely those that separate art from art, but those that divide flesh from spirit and even good from evil, until finally he arrives like Blake at a sort of ‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’” (94). He writes about “the Rousseauist”:

His breaking down of barriers and running together the planes of being results at times in ambiguous mixtures—gleams of insight that actually seem to minister to fleshliness. One may cite as an example the “voluptuous religiosity” that certain critics have discovered in Wagner. (Babbitt 1919, 210)

Thus, the romantic breaks barriers, transgresses, mixes, and—with a “voluptuous religiosity”—con-fuses. The romantic “seeks to discredit all precise distinctions whether new or old” (287). Babbitt opposes this “breaking down barriers” (94). Contemporary technoromanticism, by contrast, seeks to do precisely that. Its technologies offer the “Marriage of Heaven and Hell” which con-fuses boundaries such as those between flesh and spirit and between ethics and aesthetics. This reading of Babbitt thus suggests again that Haraway’s cyborg myth is deeply romantic. And from Babbitt’s point of view, it shows how “feminine” posthumanism’s horrible “mingling of sense and spirit” is. Babbitt’s remedy for this posthuman horror would be: restrain yourself, behave “like a man.” His humanism does not allow for mixes and confusions; he believes that boundaries and barriers need to be respected. More generally, Babbitt’s comments remain within the romanticism-classicism dichotomy that the romantics themselves set up. As many classic or Enlightenment critics of romanticism and indeed like most of us, Babbitt lives in a romantic split universe and split view of the human being, with reason and control on one side and imagination and sentiment on the other side.

Yet his book also shows that Babbitt does make some efforts to escape, not perhaps the romanticism-classicism opposition, but at least the romanticism-Enlightenment opposition. He criticizes both positivism and the “Voltairean side of the eighteenth century.” In other words, he also criticizes (a caricature of) the Enlightenment: a hyperrationalist Enlightenment. He wants to make room for his classic humanism, a kind of third way between romanticism and Enlightenment. He wants to rehabilitate Platonic and Aristotelian reason grounded in insight, “inner perception,” in order to avoid “mere” rationalism and its “quantitative method” (169) and tendency to convert man himself into a “walking theorem” (170). He writes: “A ‘reason’ that is not grounded in insight will always seem to men intolerably cold and negative and will prove unable to withstand the assault of the primary passions” (171). We need insight and experience, and they are not opposed. Babbitt’s own epistemology focuses on “good sense or practical judgment” (172). He held that the epistemological problem can only be solved “practically” (xvi). The solution is a focus on experience: “There is a center of normal human experience, and the person who is too far removed from it ceases to be probable” (173). But intuition has to mediate between particular instances and general principles (173). Intuition brings together experience and the golden mean. This epistemology distances him not only from romanticism but also from the romantic caricature of Enlightenment rationalism.

It also brings him closer to pragmatism, for instance. Babbitt rejected pragmatism for its naturalism and since he wanted to hold on to transcendent ethical principles: utility should be tested by truth rather than the other way around (see also Ryn 1997, 82). Yet his focus on experience is at least in line with pragmatism, and he comes closer to pragmatism when, at the end of the book, he writes that the full life is “found practically to make for happiness” (Babbitt 1919, 393) and especially when he praises Aristotle for his treatment of habit and indeed praises habit itself, against Rousseau’s alleged view that we should not form any habit. But then, instead of embracing the American pragmatism of his day, he rejects John Dewey for being “naturalistic” and for defending “vocational training” aimed at material efficiency rather than forming habits (386–388). Whether Babbitt is right about this, his rejection of Dewey is puzzling; maybe Babbitt could have learned something from Dewey’s account of habit.

Nevertheless, on the whole, Babbitt must be situated mainly on the side of classicism, a humanist classicism rooted in Aristotle and Plato. Although he certainly avoids the caricature of Enlightenment rationalism, his objections to Rousseau’s romanticism—which, to be fair, stand in a long dualistic tradition that runs from Aristotle to modern thinkers—seem to amount to what romantics would call a rather philistine defense of restraint and common sense. We are allowed to imagine, but the imagination must be restrained and used as an instrument for judgment. We are allowed to look at ancient civilizations for inspiration, but only if we select “the idea of proportionateness” and restraint from Greek culture—not the “pagan riot” that he thought amounted to “excessive immersion in this world” (116), not Greek polytheism, pantheism, or (later) the deist idea that “God reveals himself also through outer nature” (121), and, of course, not the romantic version of Greek culture presented by Rousseau, Novalis, and others. Dionysus is for your free time. Babbitt endorses “the great humanist virtue—decorum or a sense of proportion” (142). Distinctions need to be maintained. There needs to be humanist-classicist discipline. Romanticism is at best for the weekend or vacation, when you can enjoy your private fantasies. Real life requires us to make and maintain distinctions. Babbitt praises “the analytical head,” which discriminates between reality and dream:

It is only through the analytical head and its keen discriminations that the individualist can determine whether the unity and infinitude towards which his imagination is reaching … is real or merely chimerical. (Babbitt 1919, 167)

In this sense, Babbitt’s sober, commonsense approach launched against the incontinence of romanticism is not only very selective in its philosophical and religious imagination. Like many other criticisms of romanticism, it also remains safely within the realm of modern-romantic oppositions such as the romantic-classicism opposition, and indeed firmly within a dualist Aristotelian tradition that romanticism at least tried to overcome. His thinking brings no real end to the oscillation between two modern extremes (to use the words of Babbitt 1919, 354). With Babbitt’s humanism, we plug into a long Aristotelian tradition that certainly has its own merits, but because of its dualism, we do not really move beyond romantic-modern thinking. In its antiromanticism, Babbitt’s humanism remains firmly tied to the romantic binaries. And through its Aristotelianism, it remains affiliated with a tradition of thinking that has always been dualist through and through with regard to its view of the human being and its metaphysics. It also remains affiliated with conservatism, sexism, and fear of hybridity. To this aspect of his work, we may respond with similar words Babbitt used for Rousseau: he asked the right questions—for instance, about the nature of reality (boundaries) and about ethics—but failed to give the right answers.

There are other criticisms of romanticism, of course—for instance, Benjamin’s objections, which I mentioned in chapter 3. Romanticism has also been associated with the Nazis, who saw romantic art as “degenerate.” And in their own time, the Romantics were opposed by Goethe, who “associated Romanticism with self-indulgence, extreme subjectivity, neglect of the objective, and ultimately madness” (Allert 2004, 273). (Goethe’s humanism may be close to Babbitt’s on these points.) I next further outline and discuss more traditional criticisms of romanticism by juxtaposing Berlin’s and Popper’s view.

Berlin’s versus Popper’s Evaluation of Romanticism: Revisiting Romantic Epistemology and Discussing the Relation between Liberalism and Romanticism

Romanticism has received criticism not only from classical humanists but of course also from Enlightenment thinkers, who perceived it as an “anti-Enlightenment” or “counter-Enlightenment,” as Isaiah Berlin called it in his essay with that title (1973). Berlin, however, does not simply reject romanticism. He articulates a more nuanced view and pays attention to romantic thinking after Rousseau. For instance, he calls Schelling “the most eloquent of all the philosophers who represented the universe as the self-development of a primal, non-rational force that can be grasped only by the intuitive powers of men of imaginative genius” (22) and says about Johann Gottfried Herder—himself not a nationalist, according to Berlin—that he is “the greatest inspirer of … direct political nationalism … in Austria and Germany” (15). In contrast to many contemporary philosophers, Berlin took seriously “the great river of romanticism” (23) and spent much of his time on it. We next take a look at his book The Roots of Romanticism (1999) and confront it with Popper’s objections to romanticism to show again how ambiguous romanticism was and is, also politically.

Berlin’s book, which is based on his lectures on romanticism, starts with the claim already cited in chapter 2: Romanticism is “the largest recent movement to transform the lives and the thoughts of the Western world” and “the greatest single shift in the consciousness of the West that has occurred” (1–2). He sees romanticism as an attack on the Enlightenment and “the whole Western tradition,” which rested on three principles: (1) “all genuine questions can be answered,” (2) “all these answers are knowable,” and (3) “all the answers must be compatible with one another.” In other words, the idea was that life is “a jigsaw puzzle. … There must be some means of putting these pieces together” (26–28). Romanticism questions these principles, and Berlin sympathizes with this aspect of romanticism: he calls the belief that there is one single solution “ruinous,” especially if this is linked to the belief that “you must impose this solution at no matter what cost”; this leads to violence and despotic tyranny (169). Instead, he argues, we better accept that there are many values. Romanticism can therefore give rise to pluralism. Thus, on the one hand, romanticism also could have a good, positive impact on politics. On the other hand, Berlin acknowledges that romanticism is dangerous politically. This is especially clear in this famous article, “Two Concepts of Liberty” (1958), in which he criticizes the “true” freedom of “romantic authoritarians” (197) and writes that “the romantic faith of Fichte and Schelling would one day be turned, with terrible effect, by their fanatical German followers, against the liberal culture of the West” (167). But at the same time, in The Roots of Romanticism Berlin shows that through the notion of plurality, Romanticism also inspired a better, more sustainable, and certainly more tolerant kind of liberalism, which accepts imperfection. Berlin suggests that romanticism’s epistemology is sensitive to the unknown and to plurality, and that this gives us more hope for a tolerant society than an arrogant rationalist epistemology with claims that there is one answer and that we can fully know it.

Berlin’s nuanced treatment of Romanticism is very different from Popper’s, which is a more one-sided view of romanticism. In The Open Society and Its Enemies (1962), Popper criticized Romanticism for its “hope for political miracles”:

Aestheticism and radicalism must lead us to jettison reason, and to replace it by a desperate home for political miracles. This irrational attitude which springs from an intoxication with dreams of a beautiful world is what I call Romanticism. It may seek its heavenly city in the past or in the future; it may preach “back to nature” or “forward to a world of love and beauty”; but its appeal is always to our emotions rather than to reason. Even with the best intentions of making heaven on earth it only succeeds in making it a hell—that hell which man alone prepares for his fellow-men. (Popper 1962, 168)

Thus, whereas Berlin optimistically suggests that Romanticism may transform reason and liberalism into more modest, tolerable, and tolerating forms, Popper’s view is much more pessimistic and sees in Romanticism an essentially antiliberal project. His view is a typical “Enlightenment,” anti-Romantic view that, even more than Berlin’s, remains imprisoned in the rationality-emotion dichotomy. Nevertheless, it is clear that a political romanticism has its dangers.

Like Babbitt, Popper (1962) argues that Romanticism was based on Rousseau, a “brilliant” writer whose romanticism he sees as “one of the most pernicious influences in the history of social philosophy” (257). He locates the roots of romanticism in Rousseau’s “Platonic Idea of a primitive society” and, ultimately in Plato. In his notes to chapter 4, he says that it is “historically indeed an offspring of Platonism.” The Romantics wanted to return to Arcadia, a primitive Greek pastoral society (221). As Popper sees it, there was already a “strong element of romanticism in Plato”: his “Dorian shepherds” influenced England and France via Sanazzaro’s Arcadia (246; see also 293). Plato is presented by Popper as hating his society and as having “romantic love for the old tribal form of social life,” which is supposed to explain “the irrational, fantastic, and romantic elements of his otherwise excellent analysis.” Popper thinks there is too much “mysticism and superstition” in Plato (84). He also reads in Plato “the sweep of Utopianism, its attempt to deal with society as a whole, leaving no stone unturned,” its belief in leadership (7), and its dream of “the apocalyptic revolution which will radically transfigure the whole social world” (164).

Against this Platonic-Romantic nightmare, Popper wants to break “the spell of Plato” (7) and presents his “open society” guided by a liberalism that Berlin thought was not opposed to Romanticism, but instead had benefited from it, if not been cured by it. For Popper, here is no way out of the opposition Romanticism-Enlightenment. Biting the bullet, he accepts the kind of Enlightenment view the Romantics objected against. More precisely, he sketches an “exaggeration,” a caricature of “the” Enlightenment view, which was of course never homogeneous and was, like Romanticism itself, hybrid enough. The opposite of an organic society is an abstract one. Indeed, Popper’s open society is explicitly “abstract,” and he even imagines a society without face-to-face contact “in which all business is conducted by individuals in isolation”: a “completely abstract or depersonalized society” (174). Whereas the closed society is organic, romantic, and “magical,” the open society is abstract, “rational and critical” (294). In practice modern society is not that abstract, he concedes, but in principle it will always be more abstract than an organic one. This is not a problem for him, since he thinks the new kind of society is better. Popper is prepared to accept that the open society is more abstract because he thinks there are gains—in particular, freedom: we can freely enter personal relationships. Popper can be interpreted as himself proposing a new utopia, albeit this time a hyperrationalist one.

Interestingly, however, Popper admits that “the magical attitude has by no means disappeared from our life, not even in the most ‘open’ societies so far realized, and I think it unlikely that it can ever completely disappear” (294). With this remark, he thus casts doubt on Weber’s disenchantment thesis (an issue I return to in the next chapter) and therefore allows room for the interpretation of contemporary technological practices as technoromantic practices.

Insofar as they are romantic, however, these technological practices are then vulnerable to the same objections launched against romanticism at large.